Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux

Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux (GER) occurs in more than two-thirds of otherwise healthy infants and is common and benign in children, especially during infancy 1. Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is defined as the reflux (flow back up) of gastric contents into the esophagus (with or without regurgitation and vomiting) and it is distinguished from gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), which is gastroesophageal reflux that causes troublesome symptoms or complications such as irritability, respiratory problems, and poor growth 2. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a long-term (chronic) digestive disorder. Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a more serious and long-lasting form of gastroesophageal reflux (GER).

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is common in babies under 2 years old. Most babies spit up a few times a day during their first 3 months. Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) does not cause any problems in babies. In most cases, babies outgrow this by the time they are 12 to 14 months old. It is also common for children and teens ages 2 to 19 to have gastroesophageal reflux (GER) from time to time. This doesn’t always mean they have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

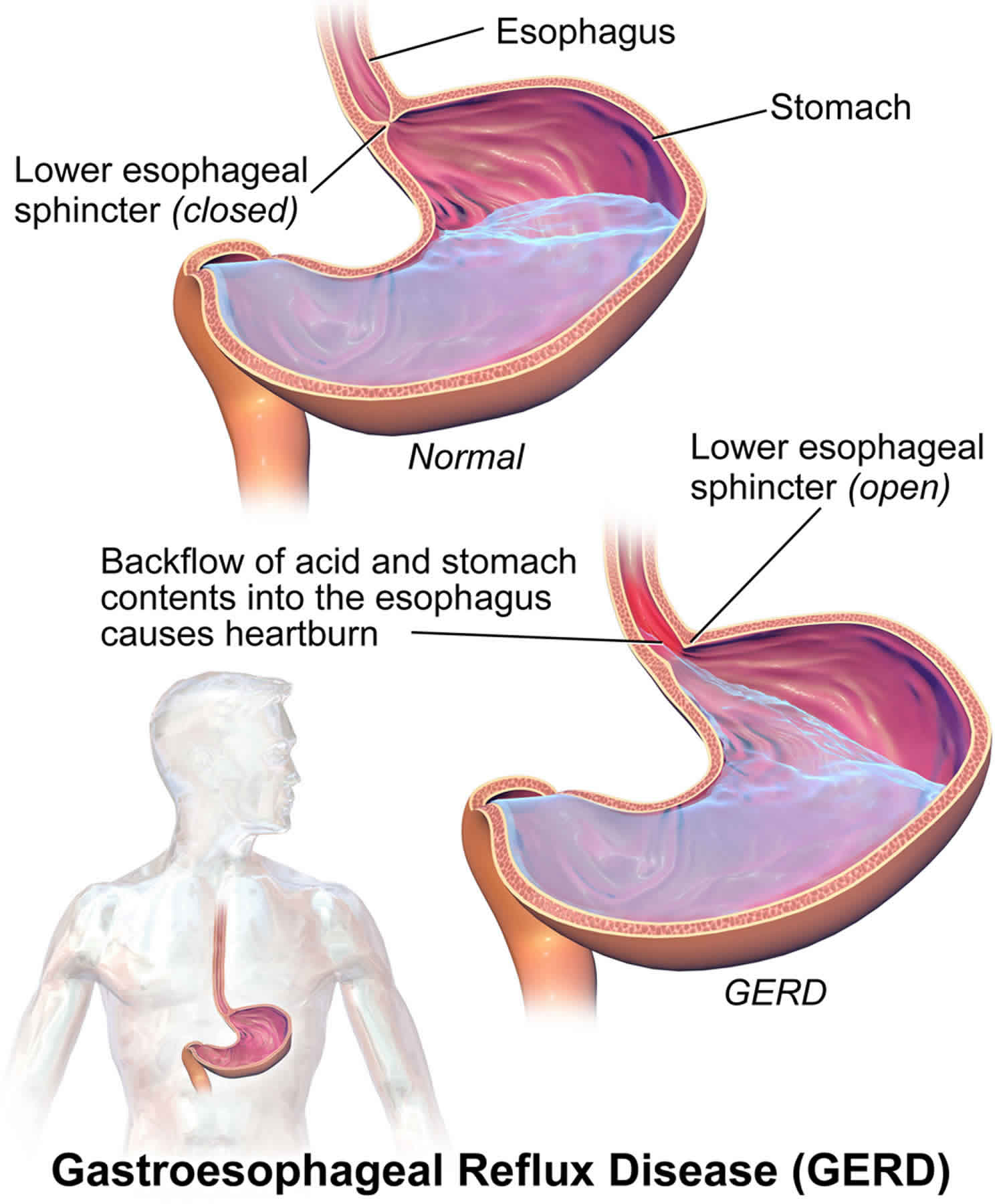

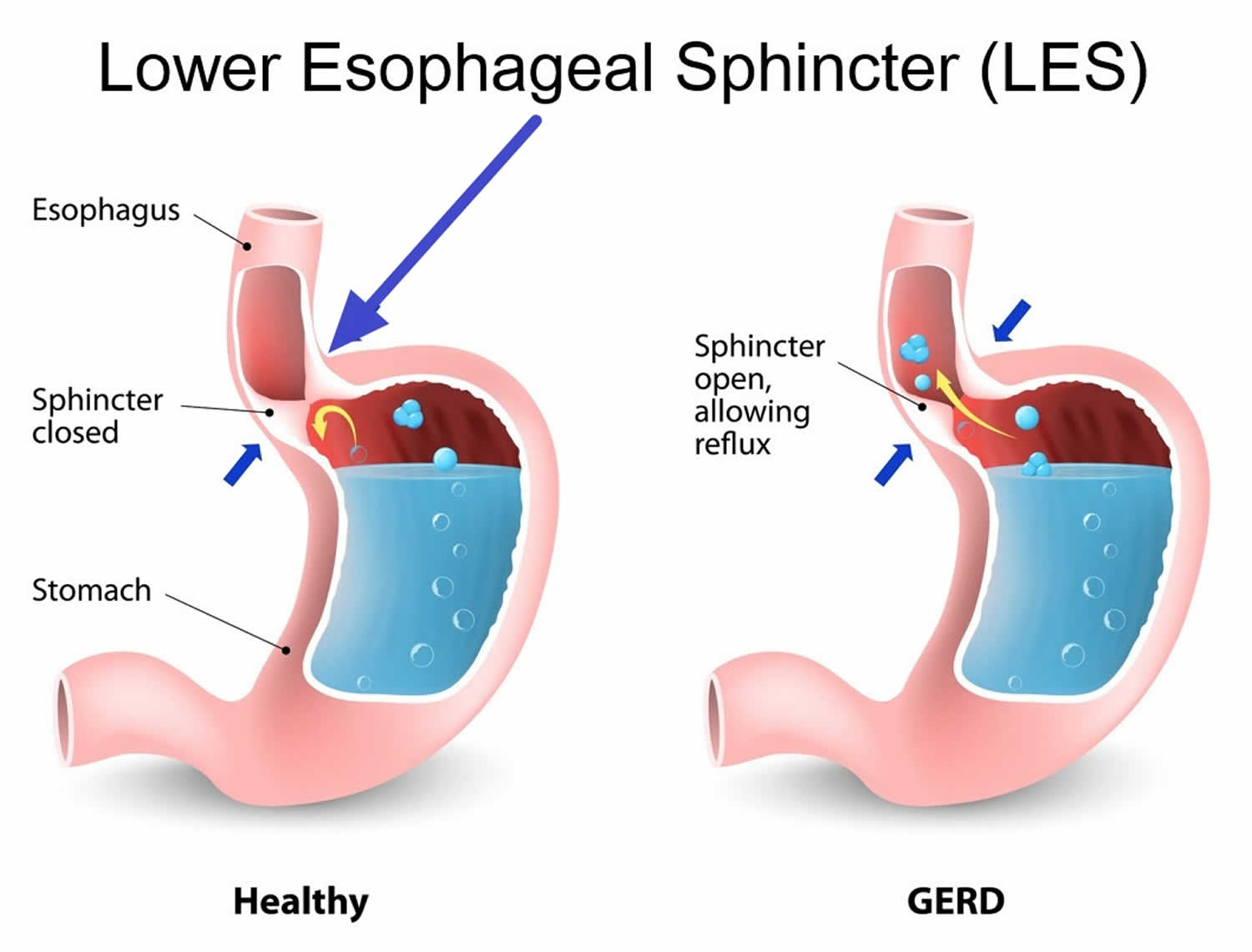

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is considered a normal physiologic process that occurs several times a day in healthy infants, children, and adults 3. Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is generally associated with transient relaxations of the lower esophageal sphincter independent of swallowing, which permits gastric contents to enter the esophagus. Episodes of gastroesophageal reflux in healthy adults tend to occur after meals, last less than 3 minutes, and cause few or no symptoms 4. Less is known about the normal physiology of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and children, but regurgitation or spitting up, as the most visible symptom, is reported to occur daily in 50% of all infants 5.

Differentiating between gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) lies at the crux of the guidelines jointly developed by the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition 2. Therefore, it is important that all health care providers who treat children with reflux-related disorders are able to identify and distinguish those children with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), who may benefit from further evaluation and treatment, from those with simple gastroesophageal reflux (GER), in whom conservative recommendations are more appropriate 3.

Figure 1. Lower esophageal sphincter (LES)

See you child’s healthcare provider if your baby or child:

- Has acid reflux and is not gaining weight

- Has signs of asthma or pneumonia. These include coughing, wheezing, or trouble breathing.

What is gastroesophageal reflux disease?

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is considered when gastroesophageal reflux (GER) causes troublesome symptoms and/or complications 6, such as failure to thrive, vomiting of blood (hematemesis), refusal to eat, sleeping problems, chronic respiratory disorders, esophagitis, stricture, anemia, apnea or apparent life threatening episodes. Complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are uncommon, however, it is important that it is identified early and managed appropriately. Referral to a specialist may be required for formal investigations such as combined intraluminal impedance and pH monitoring, barium study and/or endoscopy and biopsy. Intraluminal impedance combined with pH study is where a catheter-like nasogastric tube is inserted transnasally and the tip of catheter is allocated just above the lower esophageal sphincter to allow for detection of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) independent of pH (ie. detecting both acid and nonacid reflux).

Many babies who vomit outgrow it by the time they are about 1 year old. This happens as the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) gets stronger. For other children, taking medicines and making lifestyle and diet changes can reduce reflux, vomiting, and heartburn.

Key points about gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)

- Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a long-term (chronic) digestive disorder.

- It happens when stomach contents come back up into the food pipe (esophagus).

- Heartburn or acid indigestion is the most common symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).

- Vomiting can cause problems with weight gain and poor nutrition.

- In many cases, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can be eased by diet and lifestyle changes.

- Sometimes medicines, tube feedings, or surgery may be needed.

When does gastroesophageal reflux (GER) becomes gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)?

Your baby, child, or teen may have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) if:

- Your baby’s symptoms prevent him or her from feeding. These symptoms may include vomiting, gagging, coughing, and trouble breathing.

- Your baby has gastroesophageal reflux (GER) for more than 12 to 14 months

- Your child or teen has gastroesophageal reflux (GER) more than 2 times a week, for a few months.

What are the symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)?

Heartburn, or acid indigestion, is the most common symptom of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Heartburn is described as a burning chest pain. It begins behind the breastbone and moves up to the neck and throat. It can last as long as 2 hours. It is often worse after eating. Lying down or bending over after a meal can also lead to heartburn.

Children younger than age 12 will often have different gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms. They will have a dry cough, asthma symptoms, or trouble swallowing. They won’t have classic heartburn.

Each child may have different symptoms. Common symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) include:

- Burping or belching

- Not eating

- Having stomach pain

- Being fussy around mealtimes

- Vomiting often

- Having hiccups

- Gagging

- Choking

- Coughing often

- Having coughing fits at night

Other symptoms may include:

- Wheezing

- Getting colds often

- Getting ear infections often

- Having a rattling in the chest

- Having a sore throat in the morning

- Having a sour taste in the mouth

- Having bad breath

- Loss or decay of tooth enamel

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms may seem like other health problems. Make sure your child sees his or her healthcare provider for a diagnosis.

What causes gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)?

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is often the result of conditions that affect the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). The lower esophageal sphincter, a muscle located at the bottom of the esophagus, opens to let food into the stomach and closes to keep food in the stomach. When this muscle relaxes too often or for too long, acid refluxes back into the esophagus, causing vomiting or heartburn.

Everyone has gastroesophageal reflux from time to time. If you have ever burped and had an acid taste in your mouth, you have had reflux. The lower esophageal sphincter occasionally relaxes at inopportune times, and usually, all your child will experience is a bad taste in the mouth, or a mild, momentary feeling of heartburn.

Infants are more likely to experience weakness of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), causing it to relax when it should remain shut. As food or milk is digesting, the lower esophageal sphincter opens and allows the stomach contents to go back up the esophagus. Sometimes, the stomach contents go all the way up the esophagus and the infant or child vomits. Other times, the stomach contents only go part of the way up the esophagus, causing heartburn, breathing problems, or, possibly, no symptoms at all.

Some foods seem to affect the muscle tone of the lower esophageal sphincter, allowing it to stay open longer than normal. These include, but are not limited to, the following:

- Chocolate

- Peppermint

- High-fat foods

Other foods increase acid production in the stomach, including:

- Citrus foods

- Tomatoes and tomato sauces

What are the complications of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD)?

Some babies and children who have gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) may not vomit. But their stomach contents may still move up the food pipe (esophagus) and spill over into the windpipe (trachea). This can cause asthma or pneumonia.

The vomiting that affects many babies and children with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) can cause problems with weight gain and poor nutrition. Over time, when stomach acid backs up into the esophagus, it can also lead to:

- Inflammation of the esophagus, called esophagitis

- Sores or ulcers in the esophagus, which can be painful and may bleed

- A lack of red blood cells, from bleeding sores (anemia)

Adults may also have long-term problems from inflammation of the esophagus. These include:

- Narrowing, or stricture, of the esophagus

- Barrett’s esophagus, a condition where there are abnormal cells in the esophageal lining

How is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) diagnosed?

Your child’s healthcare provider will do a physical exam and take a health history. Other tests may include:

- Chest X-ray. An X-ray can check for signs that stomach contents have moved into the lungs. This is called aspiration.

- Upper GI series or barium swallow. This test looks at the organs of the top part of your child’s digestive system. It checks the food pipe (esophagus), the stomach, and the first part of the small intestine (duodenum). Your child will swallow a metallic fluid called barium. Barium coats the organs so that they can be seen on an X-ray. Then X-rays are taken to check for signs of sores or ulcers, or abnormal blockages.

- Endoscopy. This test checks the inside of part of the digestive tract. It uses a small, flexible tube called an endoscope. It has a light and a camera lens at the end. Tissue samples from inside the digestive tract may also be taken for testing.

- Esophageal manometry. This test checks the strength of the esophagus muscles. It can see if your child has any problems with reflux or swallowing. A small tube is put into your child’s nostril, then down the throat and into the esophagus. Then it measures the pressure that the esophageal muscles make at rest.

- pH monitoring. This test checks the pH or acid level in the esophagus. A thin, plastic tube is placed into your child’s nostril, down the throat, and into the esophagus. The tube has a sensor that measures pH level. The other end of the tube outside your child’s body is attached to a small monitor. This records your child’s pH levels for 24 to 48 hours. During this time your child can go home and do his or her normal activities. You will need to keep a diary of any symptoms your child feels that may be linked to reflux. These include gagging or coughing. You should also keep a record of the time, type of food, and amount of food your child eats. Your child’s pH readings are checked. They are compared to your child’s activity for that time period.

- Gastric emptying study. This test is done to see if your child’s stomach sends its contents into the small intestine properly. Delayed gastric emptying can cause reflux into the esophagus

How is gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) treated?

Treatment will depend on your child’s symptoms, age, and general health. It will also depend on how severe the condition is.

Diet and lifestyle changes

In many cases, diet and lifestyle changes can help to ease gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Talk with your child’s healthcare provider about changes you can make. Here are some tips to better manage gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) symptoms.

For babies:

- After feedings, hold your baby in an upright position for 30 minutes.

- If bottle-feeding, keep the nipple filled with milk. This way your baby won’t swallow too much air while eating. Try different nipples. Find one that lets your baby’s mouth make a good seal with the nipple during feeding.

- Adding rice cereal to feeding may be helpful for some babies.

- Burp your baby a few times during bottle-feeding or breastfeeding. Your child may reflux more often when burping with a full stomach.

For children:

- Watch your child’s food intake. Limit fried and fatty foods, peppermint, chocolate, drinks with caffeine such as sodas and tea, citrus fruit and juices, and tomato products.

- Offer your child smaller portions at mealtimes. Add small snacks between meals if your child is hungry. Don’t let your child overeat. Let your child tell you when he or she is hungry or full.

- If your child is overweight, contact your child’s provider to set weight-loss goals.

- Serve the evening meal early, at least 3 hours before bedtime.

Other things to try:

- Ask your child’s doctor to review your child’s medicines. Some may irritate the lining of the stomach or esophagus.

- Don’t let your child lie down or go to bed right after a meal.

- Always check with your baby’s provider before raising the head of the crib if he or she has been diagnosed with gastroesophageal reflux. This is for safety reasons and to reduce the risk for sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS) and other sleep-related infant deaths.

Medicines and other treatments

Your child’s healthcare provider may also recommend other options.

Medicines. Your child’s provider may prescribe medicines to help with reflux. There are medicines that help reduce the amount of acid the stomach makes. This reduces the heartburn linked to reflux. These medicines may include:

- H2-blockers. These reduce the amount of acid your stomach makes by blocking the hormone histamine. Histamine helps to make acid.

- Proton pump inhibitors. These help keep your stomach from making acid. They do this by stopping the stomach’s acid pump from working.

Your child’s doctor may prescribe another type of medicine that helps the stomach empty faster. If food doesn’t stay in the stomach as long as normal, reflex may be less likely to occur.

Calorie supplements. Some babies with reflux can’t gain weight because they vomit often. If this is the case, your child’s healthcare provider may suggest:

- Adding rice cereal to baby formula

- Giving your baby more calories by adding a prescribed supplement

- Changing formula to milk- or soy-free formula if your baby may have an allergy

Tube feedings. In some cases tube feedings may be recommended. Some babies with reflux have other conditions that make them tired. These include congenital heart disease or being born too early (premature). These babies often get sleepy after they eat or drink a little. Other babies vomit after having a normal amount of formula. These babies do better if they are constantly fed a small amount of milk. In both of these cases, tube feedings may be suggested. Formula or breastmilk is given through a tube that is placed in the nose. This is called a nasogastric tube. The tube is then put through the food pipe or esophagus, and into the stomach. Your baby can have a tube feeding in addition to a bottle feeding. Or a tube feeding may be done instead of a bottle feeding. There are also tubes that can be used to go around, or bypass, the stomach. These are called nasoduodenal tubes.

Surgery

In severe cases of gastroesophageal reflux with confirmed chronic gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) who have failed optimal medical therapy, are dependent on medical therapy over a long period, are significantly noncompliant with medical therapy or who have life threatening complications of GERD, surgery called fundoplication may be done 6. Your baby’s doctor may recommend this option if your child is not gaining weight because of vomiting, has frequent breathing problems, or has severe irritation in the esophagus. This is often done as a laparoscopic surgery (laproscopic fundoplication). This method has less pain and a faster recovery time. Small cuts or incisions are made in your child’s belly. A small tube with a camera on the end is placed into one of the incisions to look inside. The surgical tools are put through the other incisions. The surgeon looks at a video screen to see the stomach and other organs. The top part of the stomach is wrapped around the esophagus. This creates a tight band. This strengthens the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) and greatly decreases reflux.

Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux causes

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is the result of an abnormally functioning lower esophageal sphincter, which in infants is usually due to developmental immaturity of the lower esophageal sphincter. Infantile gastroesophageal reflux (GER) peaks at 4 months of age 7 and is usually resolved by the age 12 months 8. Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is benign and does not impact on a child’s health.

Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux symptoms

In babies with gastroesophageal reflux (GER), breast milk or formula regularly refluxes into the esophagus, and sometimes out of the mouth. Sometimes babies regurgitate forcefully or have “wet burps.” Most babies outgrow gastroesophageal reflux (GER) between the time they are 1 or 2 years old.

Kids with developmental or neurological conditions, such as cerebral palsy, are more at risk for gastroesophageal reflux (GER) and can have more severe, lasting symptoms.

Heartburn is the most common symptom of gastroesophageal reflux (GER) in kids and teens. It can last up to 2 hours and tends to be worse after meals. In babies and young children, gastroesophageal reflux (GER) can lead to problems during and after feeding, including:

- frequent regurgitation or vomiting, especially after meals

- choking or wheezing (if the contents of the reflux get into the windpipe and lungs)

- wet burps or wet hiccups

- spitting up that continues beyond a child’s first birthday (when it stops for most babies)

- irritability or inconsolable crying after eating

- refusing to eat or eating only small amounts

- failure to gain weight

Some of these symptoms may become worse if a baby lies down or is placed in a car seat after a meal.

Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux diagnosis

In older kids, doctors usually diagnose acid reflux by doing a physical exam and hearing about the symptoms. Try to keep track of the foods that seem to bring on symptoms in your child — this information can help the doctor determine what’s causing the problem.

In younger children and babies, doctors might run these tests to diagnose gastroesophageal reflux (GER) or rule out other problems:

- Barium swallow. This is a special X-ray that can show the refluxing of liquid into the esophagus, any irritation in the esophagus, and abnormalities in the upper digestive tract. For the test, your child must swallow a small amount of a chalky liquid (barium). This liquid appears on the X-ray and shows the swallowing process.

- 24-hour impedance-probe study. This is considered the most accurate way to detect reflux and the number of reflux episodes. A thin, flexible tube is placed through the nose into the esophagus. The tip rests just above the esophageal sphincter to monitor the acid levels in the esophagus and to detect any reflux.

- Milk scans. This series of X-ray scans tracks a special liquid as a child swallows it. The scans can show whether the stomach is slow to empty liquids and whether the refluxed liquid is being inhaled into the lungs.

- Upper endoscopy. In this test, doctors directly look at the esophagus, stomach, and a portion of the small intestines using a tiny fiber-optic camera. During the procedure, doctors also may biopsy (take a small sample of) the lining of the esophagus to rule out other problems and see whether gastroesophageal reflux (GER) is causing other complications.

Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux treatment

Treatment for gastroesophageal reflux (GER) depends on the type and severity of the symptoms.

In babies, doctors sometimes suggest thickening the formula or breast milk with up to 1 tablespoon of oat cereal to reduce reflux. Making sure the baby is in a vertical position (seated or held upright) during feedings can also help.

Older kids often get relief by avoiding foods and drinks that seem to trigger gastroesophageal reflux (GER) symptoms, including:

- citrus fruits

- chocolate

- food and drinks with caffeine

- fatty and fried foods

- garlic and onions

- spicy foods

- tomato-based foods and sauces

- peppermint

Doctors may recommend raising the head of a child’s bed 6 to 8 inches to minimize reflux that happens at night. They also may try to address other conditions that can contribute to gastroesophageal reflux (GER) symptoms, including obesity and certain medicines — and in teens, smoking and alcohol use.

If these measures don’t help relieve the symptoms, the doctor may also prescribe medicine, such as H2 blockers, which can help block the production of stomach acid, or proton pump inhibitors, which reduce the amount of acid the stomach produces.

Medications called prokinetics are sometimes used to reduce the number of reflux episodes by helping the lower esophageal sphincter muscle work better and the stomach empty faster.

In rare cases, when medical treatment alone doesn’t help and a child is failing to grow or develops other complications, a surgical procedure called fundoplication might be an option. This involves creating a valve at the top of the stomach by wrapping a portion of the stomach around the esophagus.

Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux prognosis

During infancy, the prognosis for gastroesophageal reflux resolution is excellent (although developmental disabilities represent an important diagnostic exception); most patients respond to conservative, nonpharmacologic treatment 9.

Most cases of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and very young children are benign, and 80% resolve by age 18 months (55% resolve by age 10 months), although some patients require a “step-up” to acid-reducing medications. Symptoms that persist after age 18 months suggest a higher likelihood of chronic gastroesophageal reflux; in such cases, the long-term risks of the condition are increased 10.

In refractory cases of gastroesophageal reflux or when complications related to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) are identified (eg, stricture, aspiration, airway disease, Barrett esophagus), surgical treatment (fundoplication) is typically necessary. The prognosis with surgery is considered excellent. The surgical morbidity and mortality is higher in patients who have complex medical problems in addition to gastroesophageal reflux.

As previously mentioned, children with neurodevelopmental disabilities, including cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, and other heritable syndromes associated with developmental delay, have an increased prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux. When these disorders are associated with motor abnormalities (particularly spastic quadriplegia), medical gastroesophageal reflux management is often particularly difficult, and suck and/or swallow dysfunction is often present. Infants with neurologic dysfunction who manifest swallowing problems at age 4-6 months may have a very high likelihood of developing a long-term feeding disorder.

Despite the immense volume of data examining diagnosis, management and prognosis related to pediatric gastroesophageal reflux, a recent review of 46 articles (out of more than 2400 publications identified) demonstrated wide variations and inconsistencies in definitions, management approaches and in outcome measures 11.

Strictures

Gastroesophageal reflux strictures typically occur in the mid-esophagus to distal esophagus. Patients present with dysphagia to solid meals and vomiting of nondigested foods. As a rule, the presence of any esophageal stricture is an indication that the patient needs surgical consultation and treatment (usually surgical fundoplication). When patients present with dysphagia, barium esophagraphy is indicated to evaluate for possible stricture formation. In these cases, especially when associated with food impaction, eosinophilic esophagitis must be ruled out prior to attempting any mechanical dilatation of the narrowed esophageal region.

Barrett esophagus

Barrett esophagus, a complication of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), greatly increases the patient’s risk of adenocarcinoma. As with esophageal stricture, the presence of Barrett esophagus indicates the need for surgical consultation and treatment (usually surgical fundoplication).

- Campanozzi A, Boccia G, Pensabene L, et al. Prevalence and natural history of gastroesophageal reflux: pediatric prospective survey. Pediatrics. 2009;123(3):779–783[↩]

- Vandenplas Y, Rudolph CD, Di Lorenzo C, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2009;49(4):498-547. doi:10.1097/MPG.0b013e3181b7f563[↩][↩]

- Gastroesophageal Reflux: Management Guidance for the Pediatrician. Jenifer R. Lightdale, David A. Gremse, SECTION ON GASTROENTEROLOGY, HEPATOLOGY, AND NUTRITION. Pediatrics May 2013, 131 (5) e1684-e1695; DOI: 10.1542/peds.2013-0421[↩][↩]

- Shay S, Tutuian R, Sifrim D, et al. Twenty-four hour ambulatory simultaneous impedance and pH monitoring: a multicenter report of normal values from 60 healthy volunteers. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99(6):1037-1043. doi:10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04172.x[↩]

- Rudolph CD, Mazur LJ, Liptak GS, et al., North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. Guidelines for evaluation and treatment of gastroesophageal reflux in infants and children: recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2001;32(suppl 2):S1–S31[↩]

- Vandenplas Y, Rudolph CD, Di Lorenzo C, et al. Pediatric gastroesophageal reflux clinical practice guidelines: joint recommendations of the North American Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (NASPGHAN) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN). J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2009;49:498–547.[↩][↩]

- Nelson SP, Chen EH, Syniar GM, Christoffel KK. Prevalence of symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux during infancy. A pediatric practice-based survey. Pediatric Practice Research Group. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 1997;151:569–72.[↩]

- Hegar B, Dewanti NR, Kadim M, Alatas S, Firmansyah A, Vandenplas Y. Natural evolution of regurgitation in healthy infants. Acta Paediatr 2009;98:1189–93.[↩]

- Pediatric Gastroesophageal Reflux. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/930029-overview#a7[↩]

- Gold BD. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: could intervention in childhood reduce the risk of later complications?. Am J Med. 2004 Sep 6. 117 Suppl 5A:23S-29S.[↩]

- Singendonk MMJ, Brink AJ, Steutel NF, van Etten-Jamaludin FS, van Wijk MP, Benninga MA, et al. Variations in Definitions and Outcome Measures in Gastroesophageal Reflux Disease: A Systematic Review. Pediatrics. 2017 Jul 27.[↩]