Pediatric inguinal hernia

Pediatric inguinal hernia happens when part of the intestines pushes through an opening near the groin area, between the belly and the thigh called the inguinal canal. Instead of closing tightly, the inguinal canal leaves a space for the intestines to slide into. With boys, you can often see a swelling in the scrotum. Although girls don’t have testicles, they do have an inguinal canal and can get hernias, too.

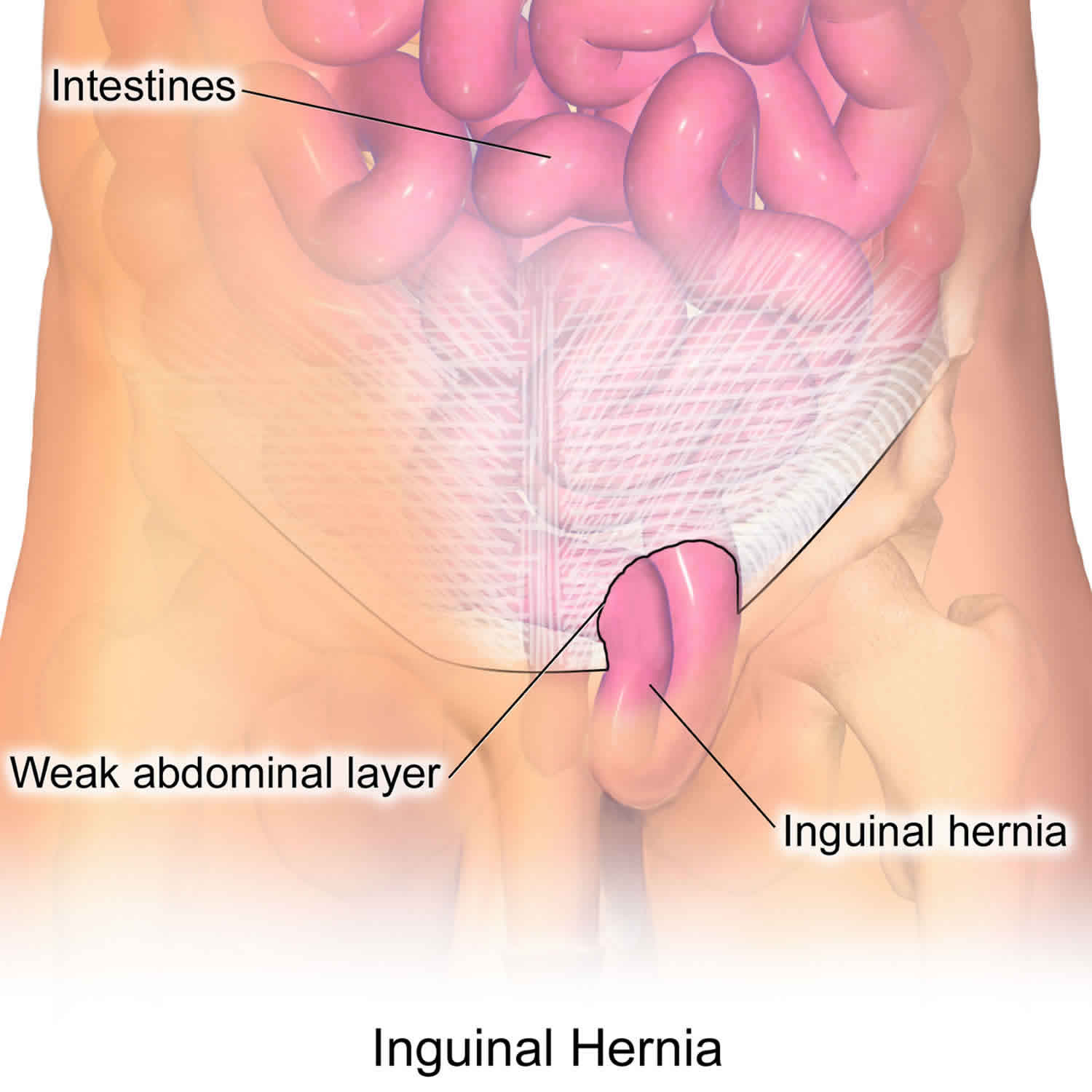

Some children are born with a weakness or hole in the muscle wall that holds the intestines in place. The abdominal lining bulges out through the hole or weak area, forming a sac, that part of the intestine pushes into. This can cause swelling and pain under the skin, especially when the child coughs, bends over, or lifts something heavy.

About 3-5% of healthy, full-term babies are born with an inguinal hernia. In premature infants, the incidence is substantially increased―up to 30%. For example, about one-third of baby boys born at less than 33 weeks gestation will have an inguinal hernia.

There are two types of inguinal hernias:

- Indirect inguinal hernias: Indirect inguinal hernias are the most common type of inguinal hernia in children and are present at birth. During fetal development, all babies have a canal (called the inguinal canal) that goes from their abdomen to their genitals. In boys, this canal allows the testicles (which develop in the abdomen) to travel to the scrotum. In both boys and girls, the canal is supposed to close off prior to birth. An indirect hernia occurs when the inguinal canal fails to completely close during fetal development, leaving an opening for abdominal contents to protrude through the defect.

- Direct inguinal hernias: Direct inguinal hernias are very rare in children. This type of hernia is caused by a weakness in the abdominal wall that allows intestines to protrude through. These hernias are more frequent in males.

In some cases, boys with an inguinal canal that fails to close may also develop a hydrocele, a collection of fluid around the testicles that occurs when fluid drains from the abdomen into the scrotum, causing it to swell.

Another type of hernia that can occur in the groin area is a femoral hernia. Femoral hernias are also very rare in children, and are caused by a weakness in the femoral canal that allows bowel or tissue to protrude from the upper thigh near the groin. This type of hernia is more common in females.

Inguinal hernias can be diagnosed by a physical examination by your child’s physician. Your child will be examined to determine if the hernia is reducible (can be pushed back into the abdominal cavity) or not. Your child’s physician may order abdominal x-rays or an ultrasound to examine the intestine more closely, especially if the hernia is no longer reducible.

Unlike some umbilical hernias, inguinal hernias will not resolve on their own. Surgery is required to correct the defect and prevent any harm to the hernia contents. If an inguinal hernia is not treated, it can cause serious problems. So doctors operate on hernias to fix the space in the muscle wall before they become an emergency.

If an inguinal hernia isn’t fixed, part of the intestine can get stuck in the muscle wall and are unable to go back into the abdomen (an “incarcerated” hernia). An incarcerated hernia will often cause a painful, firm bulge. The blood supply to the incarcerated contents can become compromised (a “strangulated” hernia), damaging the intestine and your child can become very sick. This can cause severe pain, nausea, and vomiting, and make it hard for the child to have a bowel movement. If your child has signs of an incarcerated hernia, he or she should be brought to the Emergency Department for immediate evaluation by a pediatric surgeon to minimize any damage to the contents of the hernia.

Seek medical care immediately if your child has any signs or symptoms of incarceration:

- A hernia that is stuck out and not able to be reduced (gently pushed back into the abdomen)

- A painful, firm bulge

Figure 1. Inguinal hernia in children

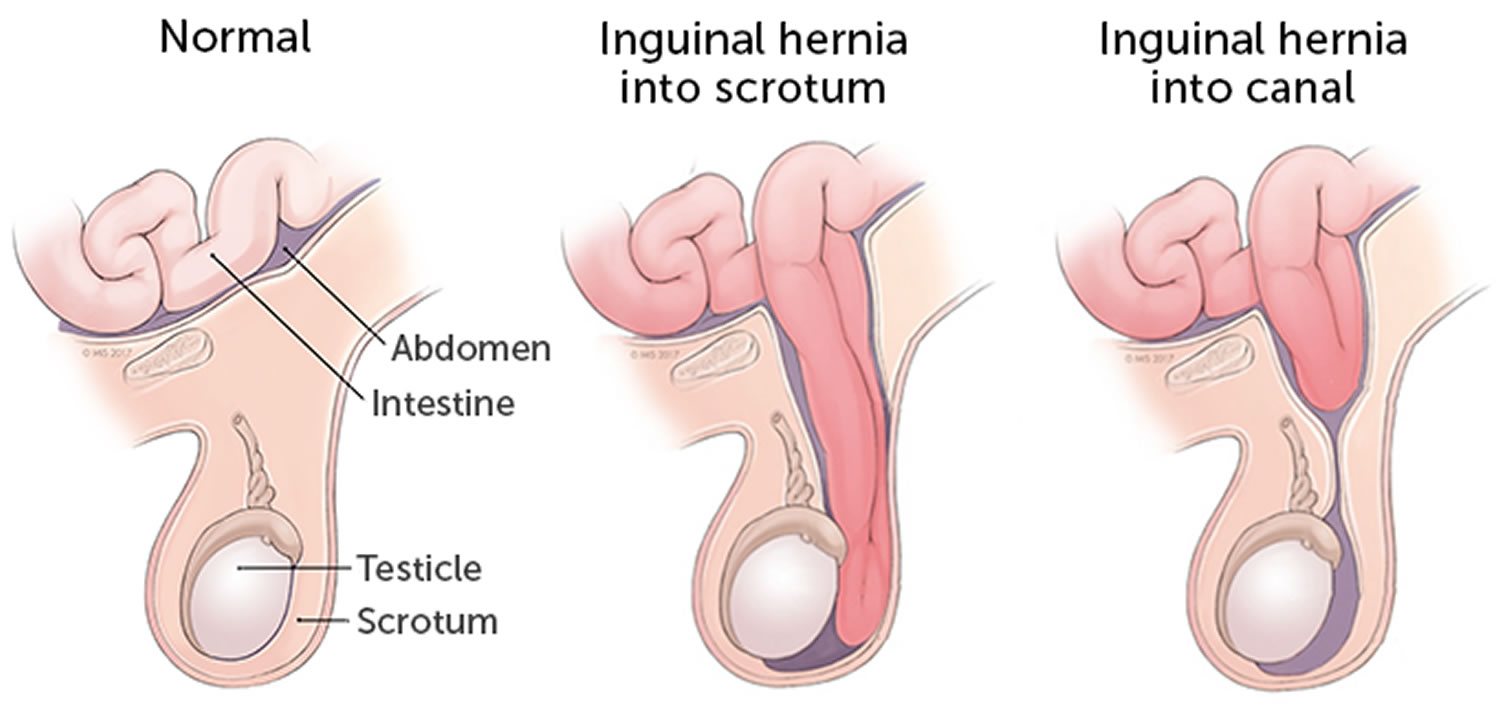

Figure 2. Inguinal hernia baby boy

Footnote: A premature baby boy with bilateral giant inguinoscrotal hernias. Because of the large size of the hernias, operative repair typically requires repair of the inguinal floor in addition to the high ligation of the indirect hernia sac.

[Source 1 ]Pediatric inguinal hernia causes

The testicles develop in boys in the back of the abdomen just below the kidney. During development of the fetus, the testicle descends from this location into the scrotum pulling a sac-like extension of the lining of its abdomen with it (inguinal hernia into scrotum). This sac surrounds the testicle into adult life, but the connection to the abdomen generally entirely resolves. If this does not occur a hernia will result with the sac extending from the abdomen through the abdominal wall and into the inguinal canal (inguinal hernia into canal), where it ends in the groin or it can persist going all the way into the scrotum and the sac surrounding the testicle.

Inguinal hernias are apparent only when there are contents from the abdominal cavity within the sac. In infants and children the sac may not be apparent if contents from the abdominal cavity have not escaped from the abdomen into the sac because the opening in the abdominal wall is too narrow to allow this to occur.

With development, the abdominal wall becomes stronger and can push contents through the opening into the sac often dilating this opening. Some factors place children at higher risk for inguinal hernias such as:

- prematurity

- undescended testicles

- a family history of hernias

- cystic fibrosis

- developmental hip dysplasia

- urethral abnormalities

Although girls do not have testicles, they do have an inguinal canal, so they can develop hernias as well. It is often the tube and ovary that fall into the hernia sac.

Occasionally, in both boys and girls, the loop of intestine that protrudes through a hernia may become stuck and cannot return to the abdominal cavity. If the intestinal loop cannot be gently pushed back into the abdominal cavity, that section of intestine may lose its blood supply. A good blood supply is necessary for the intestine to be healthy and function properly.

Pediatric inguinal hernia symptoms

Inguinal hernias appear as a bulge or swelling in the groin or scrotum. A child can have a bump in one or both sides of the groin. The swelling may be more noticeable when the baby cries and may get smaller or go away when the baby relaxes. If your physician pushes gently on this bulge when the child is calm and lying down, it will usually get smaller as the contents of the sac go back into the abdomen.

If the hernia is not reducible, then the loop of intestine may be too swollen to return through the opening in the abdominal wall and requires urgent surgery.

Other signs of inguinal hernia include:

- pain, especially when bending over, straining, lifting, or coughing

- pain that improves during rest

- weakness or pressure in the groin

- in males, a swollen or enlarged scrotum

- burning or aching feeling at the bump site

The inguinal hernia can get bigger and smaller:

- Inguinal hernia can get bigger when a child does something that creates pressure in the belly, like standing up, crying, coughing, or straining to poop.

- Inguinal hernia can get smaller again when the child lies down and is calm.

In babies, the inguinal hernia might be visible only when the infant cries, coughs, or strains to poop. Parents also might notice that the baby is cranky and eating less than usual.

Pediatric inguinal hernia diagnosis

If your child has any pain or swelling in the groin, see your doctor. Your doctor will do an exam and ask about your child’s medical history.

To feel the hernia as it moves into the groin or scrotum, the doctor might have your child stand and cough. The doctor will gently try to massage the hernia back into its proper place in the abdomen. A hernia that can be massaged back into place is called a “reducible” hernia. But these also need surgery because they won’t stay in place.

If the hernia is not reducible, the doctor may order an X-ray or an ultrasound to get a better look at the intestine.

Pediatric inguinal hernia treatment

Pediatric inguinal hernia treatment will be determined by your child’s physician based on the following:

- your child’s age, overall health, and medical history

- the type of hernia

- whether the hernia is reducible (can be pushed back into the abdominal cavity) or not

- your child’s tolerance for specific medications, procedures or therapies

An operation is necessary to treat an inguinal hernia. It will be surgically repaired fairly soon after it is discovered, since the intestine can become stuck in the inguinal canal. When this happens, the blood supply to the intestine can be cut off, and the intestine can become damaged. Inguinal hernia surgery is usually performed before this damage can occur.

The surgery to repair an inguinal hernia is usually a day surgery, meaning your child will go home the same day as the procedure. Premature babies who are less than 60 weeks post-conception age may require an overnight stay for post-anesthetic apnea (breath holding) monitoring. The procedure will be done under general anesthesia. Your child’s surgeon will discuss with you the surgical procedure that is best for your child.

The surgical approach for repair of an inguinal hernia depends on the clinical situation:

- Open repair: A tiny incision is made in the groin (along the skin crease) and the hernia is closed using sutures. The overlying skin is sealed with DERMABOND, a sterile, liquid adhesive that will hold the edges of your child’s wound together and act as a waterproof dressing.

- Open repair with laparoscopic evaluation of the other side: The procedure is done in the same manner as the open repair; however, prior to closing the hernia, a small camera (laparoscope) is used to check for the presence of a hernia on the opposite side of the groin or scrotum. If a second hernia is present, another tiny incision is made on the opposite side of the groin and the other hernia is repaired.

Using a laparoscope to evaluate the opposite side for a hernia is done in certain situations depending upon the patient’s age, since hernias on both sides are more common in babies and small children. The overlying skin is sealed with DERMABOND. - Laparoscopic repair: A small camera (laparoscope) is placed through an incision in the belly button. The hernia repair is done using surgical instruments that are inserted through one or two tiny incisions in the lower portion of the abdomen. All sutures that are used are dissolvable and the overlying skin will be sealed with DERMABOND.

DERMABOND usually stays in place for 5 to 10 days before it starts to fall off. You should not pick, peel, or rub the DERMABOND, as this could cause your child’s wound to open before it is healed.

Once it sets, the adhesive can get wet (as in a shower) the same day as the procedure, but should not routinely be submerged under water (as in swimming) for seven days. Do not apply any ointments such as Vaseline or Neosporin to the incision while the DERMABOND is in place until seven days after surgery.

Once the hernia is closed, either spontaneously or by surgery, it is unlikely it will reoccur.

Pediatric inguinal hernia repair

For pediatric inguinal hernia, elective herniorrhaphy is indicated to prevent incarceration and subsequent strangulation. Pediatric inguinal hernia repair is an outpatient procedure in the otherwise healthy full-term infant or child. Postpone the operation in the event of upper respiratory tract infection, otitis media, or significant rash in the groin.

Only 3 procedures are necessary for the surgical repair of indirect inguinal hernias in children: (1) high ligation and excision of the patent sac with anatomic closure, (2) high ligation of the sac with plication of the floor of the inguinal canal (the transversalis fascia), and (3) high ligation of the sac combined with reconstruction of the floor of the canal. Each procedure can be accomplished with an open or laparoscopic technique 2.

The first procedure, high ligation and excision of the patent sac with anatomic closure, is the most common operative technique. It is appropriate when the hernia is not very large and has not been present for long. The second procedure, high ligation of the sac with plication of the floor of the inguinal canal (the transversalis fascia), is necessary when the hernia has repeatedly passed through the internal ring and has enlarged the ring, partially destroying and causing weakness in the inguinal floor. The third procedure, high ligation of the sac combined with reconstruction of the floor of the canal, is occasionally necessary in small children with large hernias or when the hernia is long-standing.

The protruding hernia causes gradual enlargement of the ring, progressing to complete breakdown of the transversalis fascia that forms the floor of the inguinal canal. The McVay or Bassini technique of herniorrhaphy is preferred. A description and discussion of the total laparoscopic needle-assisted technique for repair of pediatric inguinal hernias is below; it is a new and innovative procedure that is gaining significant popularity among pediatric surgeons.

Open repair of the pediatric inguinal hernia

The patient should be placed on the operating table in a supine position with his or her legs slightly abducted. The lower abdomen and inguinoscrotal or inguinolabial area and upper thighs must be included in the operative field. The hernia contents must be completely reduced into the peritoneal cavity before the procedure.

Incision is made in the skin of the inguinal crease just lateral to the pubic tubercle. The skin incision is typically small (1-2 cm). Electrocautery is used to control any bleeding that may occur.

Next, identify and incise the Scarpa fascia. In young children, the Scarpa fascia may be confused with the aponeurosis of the external oblique. However, the Scarpa fascia is smooth, does not have any fibrous bands, and does not glisten like the aponeurosis. In addition, a layer of fat is found beneath the Scarpa fascia but not under the external oblique.

One should not raise any skin flaps. Dissection is started through the external oblique at the lateral aspect of the incision and extended to the inguinal ligament.

The external ring is identified by dissecting medially along the inguinal ligament. The ring is incised, taking care to avoid injury to the usually visible ilioinguinal nerve. This incision reveals the cremaster fibers of the cord.

The hernia sac can be identified in the anteromedial aspect of the cord, and medial retraction of the sac reveals the underlying testicular vessels and vas deferens. Fine tissue forceps are used to tease these structures away from the hernia sac. An Allis clamp may be placed around the vas and the testicular vessels to keep them away from further dissection.

The sac can then be clamped and divided. The proximal sac is mobilized to the internal ring, which is often signified by the presence of retroperitoneal fat.

Once the sac is confirmed to be empty, it is twisted on itself and doubly suture-ligated with sutures (eg, 4-0 or silk or Vicryl sutures can be used).

If the ring is not enlarged, the distal sac is opened to drain any residual fluid and the sac is partially excised. Then, closure is accomplished in layers with absorbable sutures.

If the internal ring is enlarged, the cord must be elevated from its bed with a soft rubber drain. A silk suture between the transversalis fascia and the inguinal ligament can be used to tighten the ring. Alternatively, a modified Bassini type of repair can be used to reinforce the inguinal floor.

If destruction of the canal floor is present, a reconstructive procedure, such as that of Bassini or McVay, is necessary.

The McVay type of repair incorporates a relaxing incision in the rectus sheath that allows the conjoined tendon to be pulled down to the Cooper ligament and the femoral sheath.

The incised aponeurosis of the external abdominal oblique muscle is closed with interrupted 4-0 or 5-0 silk sutures or a continuous 4-0 polyglycolic acid suture.

Typically one or two interrupted absorbable sutures are used to close the Scarpa fascia. The skin can be closed with absorbable sutures

Laparoscopic needle-assisted repair of inguinal hernia

A new and innovative technique for repair of inguinal hernia in young children using a total laparoscopic approach has been described. [11] The technique is described as laparoscopic needle-assisted repair.

Standard laparoscopy is performed via a small 5-mm umbilical port with a 5-mm, 30 º- angled laparoscope. Once the indirect inguinal hernia is identified, the laparoscopic repair is performed.

The first step is to clearly define the inguinal hernia and the lateral and medial border of the open internal inguinal ring. This is accomplished by probing the groin region with a small 22-gauge needle.

Under careful laparoscopic-guided visualization, a 22-gauge Tuhoi spinal needle with a 2-0 Prolene suture thread inside the barrel of the needle is inserted and passed underneath the peritoneum and the inguinal ligament, lateral to the internal inguinal ring, away from the spermatic vessels and vas. All needle movements are performed by the operating surgeon from outside the body cavity under direct laparoscopic control so that the position of the tip of the needle can be precisely placed at the desired location inside the peritoneal cavity. The Prolene thread is than pushed through the barrel of the needle into the abdominal cavity, creating an internal “loop.” The needle is pulled out, leaving the Prolene loop of the thread inside the abdomen.

From the outside the patient’s body, one of the threaded ends is introduced again into the barrel of the spinal needle, and the needle is passed through the same skin puncture point, through the medial aspect of the internal inguinal ring, under the peritoneum. Again, the vas and vessels are mobilized to stay away from the needle, in order to prevent any injury. Once the tip of the needle is in the desired position next to the loop of Prolene, the thread is pushed in so that it passes through the loop. At this point, the thread-loop is pulled out of the abdomen, with the thread end caught by the loop. In this way, the suture thread of Prolene is placed around the internal inguinal ring under the peritoneum, creating a complete purse-string suture with the ends of the suture coming out of the same skin needle hole in the groin region. The knot is tied to close the internal inguinal ring and hernia opening. With this technique the knot is buried in the subcutaneous tissue.

Follow-up care

After surgery, your child’s incision may appear to be slightly swollen. In boys, the scrotum may also appear swollen. This will go away over the next few weeks. Your child will not be able to participate in physical education or sports for 2 to 3 weeks after surgery.

We will schedule your child for a follow-up appointment in our surgery clinic 2 to 4 weeks after the procedure, at which time we will evaluate the repair and your child’s recovery.