Perianal cyst

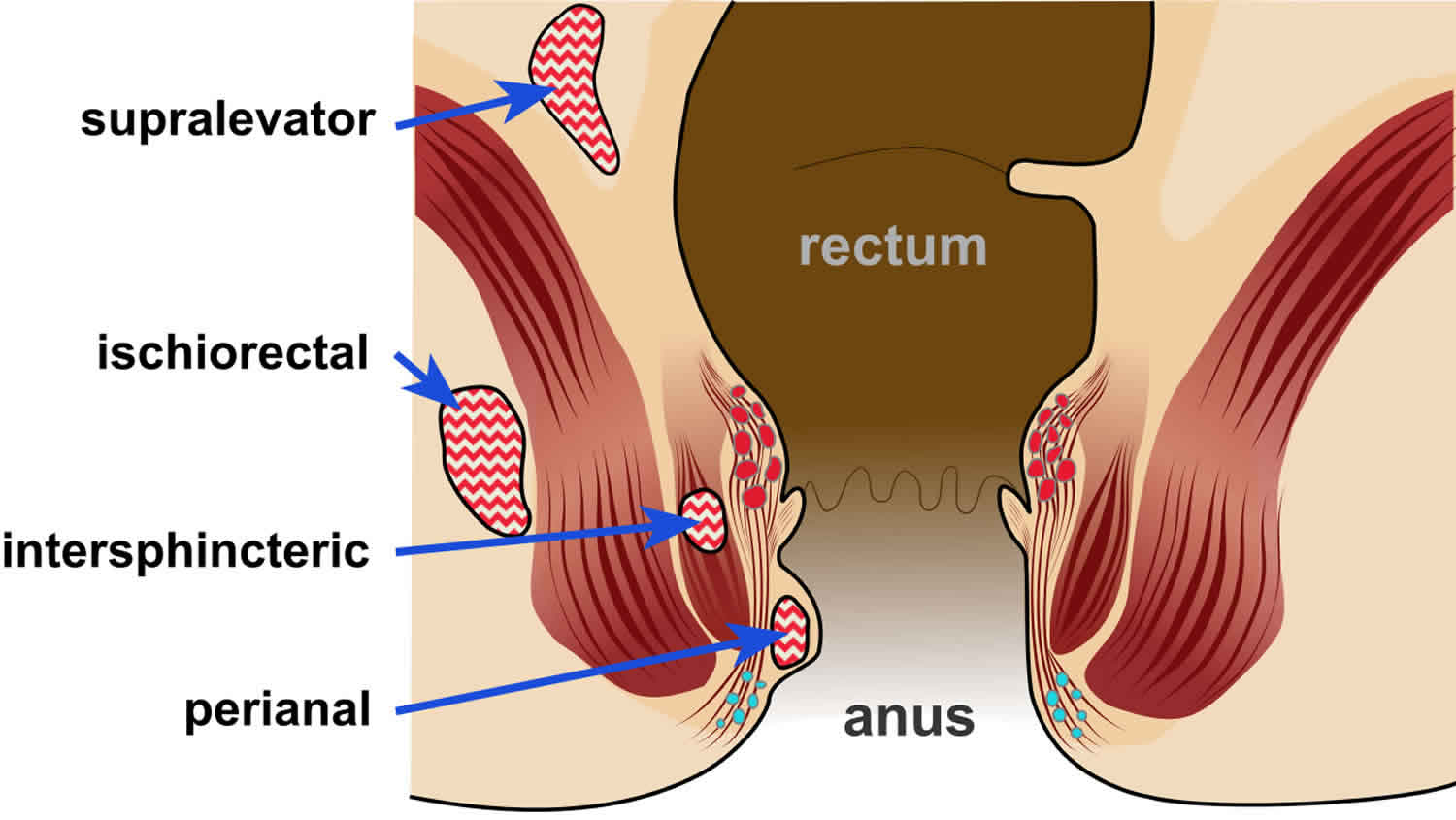

Perianal cysts are of one of the following four types 1:

- Epidermoid cysts

- Dermoid cysts

- Anal duct/gland cysts

- Sacrococcygeal teratomas

A cyst is defined as an abnormal sac with a membranous lining, containing gas, fluid, or semisolid material.

Although perianal cysts differ with respect to epidemiology, cause, and outcome, the diagnostic evaluation of all perianal cyst types is similar and must include ruling out malignancy. Although this is an unusual presentation, rare cases of cancer discovered in perianal cysts have been reported.

Sacrococcygeal teratomas in adults most commonly are benign; these are also called mature teratomas. Rare cases have been reported of adults with malignant teratomas, which contain frankly malignant tissue of germ cell origin, such as germinoma (eg, seminoma or dysgerminoma) and choriocarcinoma, in addition to mature and/or embryonic tissues 2.

Tumors containing malignant non ̶ germ cell elements have been termed teratoma with malignant transformation; such transformation has included adenocarcinoma or squamous cell carcinoma found in mature teratomas of adults.

Patients with either a malignant teratoma or a benign teratoma with malignant transformation have a considerable increase in mortality, dying from the disease within 2 months to 2 years. This is in comparison with patients with benign disease, who are alive without disease as long as 4 years after treatment.

The majority of teratomas in infancy and childhood are also benign; however, in this population, a tendency exists toward an increase in malignant potential with increasing age. Therefore, surgical excision is performed almost uniformly.

Perianal cyst causes

Anal duct and gland cysts

The cause of anal duct cysts is unknown. One theory states that anal glands lose their communication with the anal ducts during development but retain their ability to secrete fluid and, thus, create a cyst. Another theory suggests that the anal glands are not canalized during embryogenesis. As the epithelium in these noncanalized nests of glandular tissue secrete fluid, cystic formations result.

Kulayat et al reported that three out of 97 anal duct cyst cases had perianal involvement 3. However, these cysts occur more commonly in the presacral, precoccygeal, and retrorectal spaces or high in the anterior or posterior anal canal. Anal duct cysts present most commonly in the third decade of life, and they have a higher incidence in men than in women.

Sacrococcygeal teratomas

Various theories also exist to explain the origin of sacrococcygeal teratomas. These include nonsexual reproduction of germ cells within the gonads or in extragonadal sites, wandering germ cells of nonparthenogenetic origin left behind during the migration of embryonic germ cells from yolk sac to gonad, or origin in other totipotential embryonic cells.

Teratomas, including sacrococcygeal teratomas, are classified into the following three histopathologic categories:

- Mature

- Immature

- Malignant

Mature teratomas (also known as benign teratomas) contain obvious epithelium-lined structures, mature cartilage, and striated or smooth muscle. Immature teratomas have areas of primitive mesoderm, endoderm, or ectoderm mixed with more mature elements in a highly cellular stroma with mitotic figures.

Malignant teratomas, in addition to mature and/or embryonic tissues, have frankly malignant tissue of germ cell origin, such as germinoma (ie, seminoma or dysgerminoma) and choriocarcinoma. Tumors containing malignant non ̶ germ cell elements, including adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma, are referred to as teratoma with malignant transformation.

The sacrococcygeal area is the most frequent site of teratoma in infancy, reported to occur in 1 of 35,000-40,000 births (though a study from southern Sweden cited a higher figure, 1 in 13,982) 4. A female predominance exists. Sacrococcygeal teratoma is the most common neoplasm in newborns 5; it rarely presents in adulthood 6. Unlike teratomas in infants, which are externally visible in 90% of cases, sacrococcygeal teratomas in adults are confined mostly to the intrapelvic space.

Dermoid cysts

Displaced ectodermal structures along the lines of embryonic fusion may cause dermoid cysts. The wall of the cyst is formed of epithelium-lined connective tissue, including skin appendages, and contains keratin, sebum, and hair.

Dermoid cysts are usually found in the genital and perianal areas in adults; however, in children, they are seen most often in the head and neck regions. About 40% of dermoid cysts are present at birth, and 70% are present by age 5 years. They are more common in women than in men.

Epidermoid cysts

These result from inflammation around a pilosebaceous follicle and frequently are seen following the more severe lesions of acne vulgaris. Some epidermoid cysts may result from deep implantation of epidermis by blunt penetrating injury or following a surgical procedure.

Epidermoid cysts are relatively common and mostly affect young and middle-aged adults. They are rare in childhood.

Perianal cyst symptoms

Patients commonly complain of perianal swelling, with pain or soreness if inflamed. Occasional painless rectal bleeding may be present. If the mass is large enough, patients may complain of constipation due to rectal obstruction or recurrent urinary tract infections due to obstruction of the bladder neck.

If a sacrococcygeal teratoma has directly invaded the nerve roots of the cauda equina or metastasized to the spinal cord, the patient may complain of neurologic symptoms, such as lower-extremity numbness or weakness; however, this is very rare. Upon physical examination, perianal cysts present similarly.

Anal duct and gland cysts

Typically, these present with perianal soreness, tenderness, swelling, and induration. These smooth, subcutaneous, spherical nodules may vary in size from 1 to 2 cm. The anterior anus is involved more commonly than the posterior anus.

Sacrococcygeal teratomas

Commonly, these are large, soft presacral masses felt during the rectal examination during a routine physical examination; they may range from 5 to 25 cm in diameter. Sacrococcygeal teratomas may be asymptomatic upon initial presentation; an infected teratoma may present as an abscess 7.

Epidermoid cysts

An epidermoid cyst, because it is situated in the dermis, raises the epidermis to produce a firm, elastic, dome-shaped mass that is mobile over deeper structures. It may have a central, keratin-filled punctum and vary in size from a few millimeters to 50 mm. They may be solitary but more commonly are multiple. Over time, these cysts may enlarge and occasionally become inflamed and tender. When epidermoid cysts present in the perianal region, they are superficial and yellowish to white in color 8.

Dermoid cysts

Typically, these present as subcutaneous, spherical nodules ranging from 6 to 60 mm in diameter, depending on the involved site. Many have a sinus opening from which hair projects. Recurrent infection may be a problem.

Perianal cyst diagnosis

The evaluation of perianal cysts include the following:

- Computed tomography (CT) – CT of the pelvis may be useful for showing a cystic mass in the perianal region and for helping to rule out anal cancer or abscess

- Endoscopy – This may be recommended to help rule out cancer—specifically, anal or rectal cancer

- Cytologic examination – The cyst may be drained and the fluid sent for cytology; if a question of malignancy exists, the cyst still may be drained, but some controversy remains as to whether or not this may seed the tract

- Laboratory tests – No particular laboratory tests are useful in the diagnosis of perianal cysts

Perianal cyst treatment

No particular medical treatment is available for perianal cysts. Complete surgical excision is the treatment of choice. As for any procedure, surgical treatment is contraindicated if the patient is a poor operative candidate. Careful risk-benefit consideration is needed for individuals with severe pulmonary and/or cardiac disease.

Perianal cyst surgery

The majority of sacrococcygeal teratomas can be removed through a sacral approach; however, if the tumor extends greatly into the pelvis and retroperitoneum, an additional abdominal incision may be necessary to completely excise the tumor. Laparoscopic approaches have been described 9.

For sacrococcygeal teratomas, it is recommended that the coccyx also be removed; failure to remove it has been associated with a high risk of recurrence. For histologically benign teratomas, adequate surgical excision is virtually curative 10. For malignant teratomas, surgical excision alone is inadequate, and patients should receive additional treatment with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or both. It has been suggested that same low-stage sacrococcygeal teratomas may be treatable with resection and observation alone, with chemotherapy provided only in the event of recurrence 11.

Of special concern is the association between genetic presacral teratomas and urinary and anal anomalies. The Currarino triad is an autosomal dominant condition that includes anorectal stenosis, a sacral bony anomaly in which the sacrum has a crescent shape, and a presacral mass. This mass can be a teratoma and is rarely malignant. In these cases, care should be taken when excising the mass, because there may be communication with the dura mater and the cerebrospinal fluid.

For the three other cyst types, a transrectal approach may be used. If an abscess is suggested, incision and drainage are recommended, with an appropriate course of antibiotics.

The fetus with sacrococcygeal teratoma has an increased risk of perinatal complications (eg, from tumor rupture or dystocia). In some cases, in-utero interventions such as tumor debulking and cyst aspiration may be considered.

Sananes et al 12 conducted a retrospective study of fetuses with high-risk large sacrococcygeal teratomas with the aims of assessing the efficacy of minimally invasive ablation of these tumors and determining the relative efficacy of vascular and interstitial ablation. They found that this minimally invasive approach appeared to improve outcome and that vascular ablation might be superior to interstitial ablation, but they noted that the latter finding would require further investigation in a larger multicenter prospective study.

Complications

Bleeding and infection are potential complications of any surgical procedure. Profuse bleeding is rarely a major complication, because no major blood vessels are present in the perianal region. Good hygiene during wound healing can reduce the risk of infection.

Fistula formation is a rare complication; however, the risk may be slightly increased in dermoid cysts because they may contain hair projecting from a sinus tract.

Fecal incontinence also is a rare complication; the risk depends on the position of the cyst and on the age, sex, and past medical history of the patient.

In children, sacrococcygeal teratomas can cause such problems as ureteric obstruction and resultant hydronephrosis. Neurogenic bladder is a potential complication of sacrococcygeal teratoma and of its surgical treatment 13.

Postoperative care

No particular diet affects the natural history of these cysts. However, patients should be placed on a high-fiber diet postoperatively to prevent straining-induced wound dehiscence.

Patients with perianal cysts are not limited in their activities. Postoperatively, patients may find sitz baths helpful for decreasing their discomfort.

Postoperative chemotherapy or radiotherapy may be necessary in patients with malignant teratomas or teratomas with malignant transformation. Because sacrococcygeal teratomas are rare, no standard recommendation exists for the use of chemotherapy or radiation therapy. For sacrococcygeal teratomas, postoperative outpatient follow-up is crucial 14. If complete resection is accomplished, a full physical examination should be performed periodically, with emphasis on assessment of the perineal and presacral area by rectal examination. Computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful if a recurrence is suggested.

Perianal cyst prognosis

For the three nonteratoma types of perianal cysts, the prognosis is excellent.

For patients with benign teratomas, adequate surgical excision is curative. Malignant teratomas or teratomas with malignant transformation have a less favorable prognosis, with neurologic involvement being an added negative prognostic factor 15. A multi-institutional study by Akinkuoto et al found that a tumor volume–to–fetal weight ratio higher than 0.12 before 24 weeks’ gestation was objectively predictive of poor outcomes in fetuses with sacrococcygeal tumors 16.

Risks for recurrence include immature or malignant histology and incomplete resection 17. One study examining recurrence risk did not find an association between microscopic involvement at the resection margins and recurrence, as long as the involvement was not yolk sac tumor histology. Recurrence risk is greatest within the initial 3 years after resection; late recurrences rarely occur.

- Perianal cysts. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/192071-overview[↩]

- Lianos G, Alexiou G, Zigouris A, Voulgaris S. Sacrococcygeal neoplastic lesions. J Cancer Res Ther. 2013 Jul-Sep. 9(3):343-7.[↩]

- Kulaylat MN, Doerr RJ, Neuwirth M, et al. Anal duct/gland cyst: report of a case and review of the literature. Dis Colon Rectum. 1998 Jan. 41(1):103-10.[↩]

- Hambraeus M, Arnbjörnsson E, Börjesson A, Salvesen K, Hagander L. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: A population-based study of incidence and prenatal prognostic factors. J Pediatr Surg. 2016 Mar. 51 (3):481-5.[↩]

- Lee MY, Won HS, Hyun MK, Lee HY, Shim JY, Lee PR, et al. Perinatal outcome of sacrococcygeal teratoma. Prenat Diagn. 2011 Dec. 31 (13):1217-21.[↩]

- Luk SY, Tsang YP, Chan TS, Lee TF, Leung KC. Sacrococcygeal teratoma in adults: case report and literature review. Hong Kong Med J. 2011 Oct. 17(5):417-20.[↩]

- Nguyen CT, Kratovil T, Edwards MJ. Retroperitoneal teratoma presenting as an abscess in childhood. J Pediatr Surg. 2007 Nov. 42(11):E21-3.[↩]

- Jain V, Misra S, Tiwari S, Rahul K, Jain H. Recurrent Perianal Sinus in Young Girl Due To Pre-sacral Epidermoid Cyst. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2013 Jul. 3 (3):458-60.[↩]

- Gödeke J, Engel V, Münsterer O. [Laparoscopic-assisted mobilisation and resection of a sacrococcygeal teratoma Altman type III]. Zentralbl Chir. 2017 Jun. 142 (3):255-256.[↩]

- Lee KH, Tam YH, Chan KW, Cheung ST, Sihoe J, Yeung CK. Laparoscopic-assisted excision of sacrococcygeal teratoma in children. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008 Apr. 18 (2):296-301.[↩]

- Egler RA, Gosiengfiao Y, Russell H, Wickiser JE, Frazier AL. Is surgical resection and observation sufficient for stage I and II sacrococcygeal germ cell tumors? A case series and review. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2017 May. 64 (5).[↩]

- Sananes N, Javadian P, Schwach Werneck Britto I, Meyer N, Koch A, Gaudineau A, et al. Technical aspects and effectiveness of percutaneous fetal therapies for large sacrococcygeal teratomas: cohort study and literature review. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2016 Jun. 47 (6):712-9.[↩]

- Ozkan KU, Bauer SB, Khoshbin S, et al. Neurogenic bladder dysfunction after sacrococcygeal teratoma resection. J Urol. 2006 Jan. 175(1):292-6; discussion 296.[↩]

- Padilla BE, Vu L, Lee H, MacKenzie T, Bratton B, O’Day M, et al. Sacrococcygeal teratoma: late recurrence warrants long-term surveillance. Pediatr Surg Int. 2017 Nov. 33 (11):1189-1194.[↩]

- Isaacs H Jr. Perinatal (fetal and neonatal) germ cell tumors. J Pediatr Surg. 2004 Jul. 39(7):1003-13.[↩]

- Akinkuotu AC, Coleman A, Shue E, Sheikh F, Hirose S, Lim FY, et al. Predictors of poor prognosis in prenatally diagnosed sacrococcygeal teratoma: A multiinstitutional review. J Pediatr Surg. 2015 May. 50 (5):771-4.[↩]

- Derikx JP, De Backer A, van de Schoot L, et al. Factors associated with recurrence and metastasis in sacrococcygeal teratoma. Br J Surg. 2006 Dec. 93(12):1543-8.[↩]