What is PFO

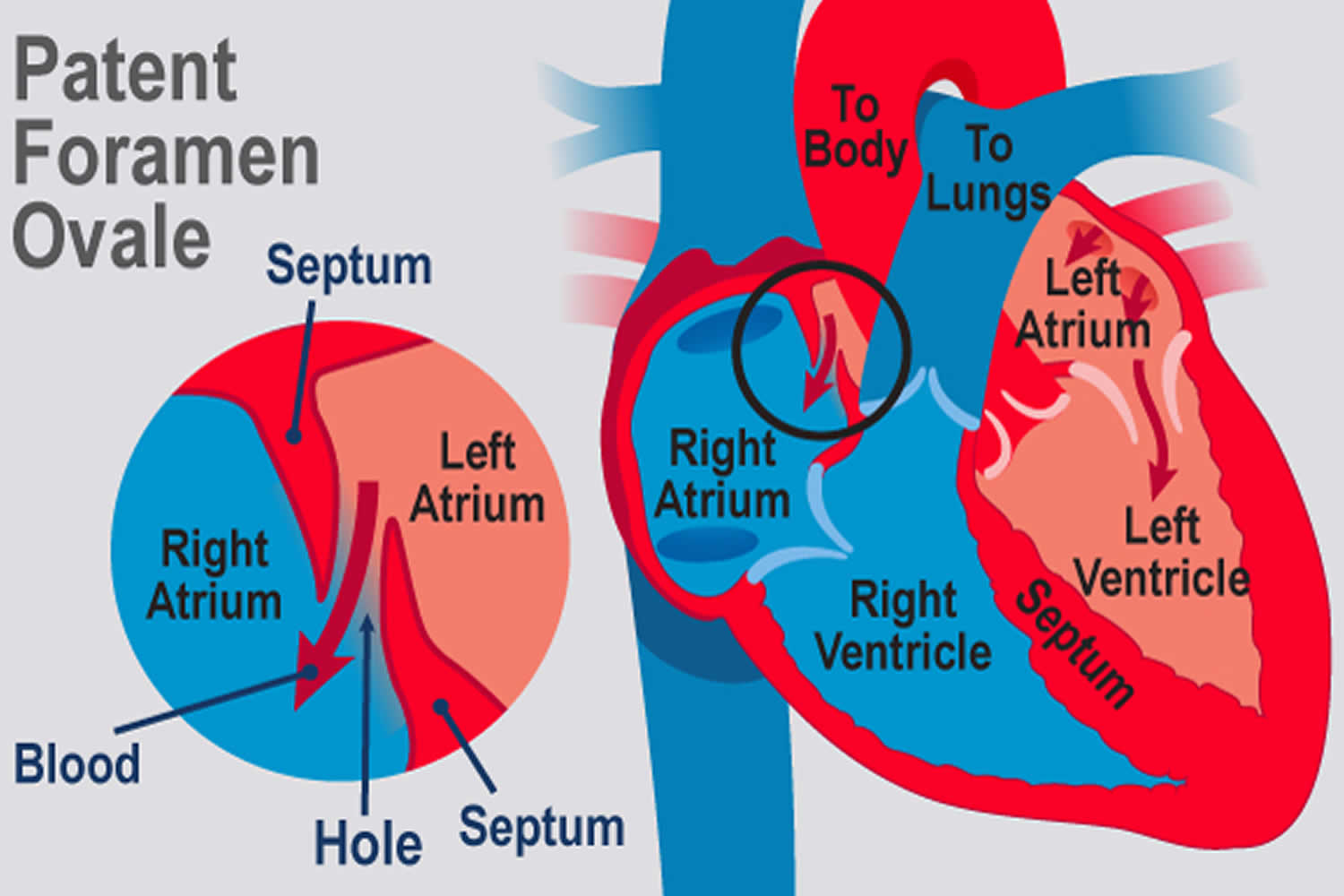

PFO is short for patent foramen ovale, which is a hole in the heart that didn’t close the way it should after birth. During fetal development, a small flap-like opening — the foramen ovale is normally present in the wall between the right and left upper chambers (atria) of the heart. Foramen ovale normally closes during infancy. When the foramen ovale doesn’t close, it’s called a patent foramen ovale or PFO.

PFO occurs in about 25 percent of the normal population, but most people with the PFO never know they have it. A patent foramen ovale is often discovered during tests for other problems. Learning that you have a PFO is understandably concerning, but most people never need treatment for this disorder.

PFO (patent foramen ovale) that abnormally persists into adulthood can contribute to inter-atrial, right-to-left shunting of deoxygenated blood and potential for shunting venous thromboembolism to arterial circulation 1. This implicates PFO as the underlying pathophysiologic determinant of several conditions including cryptogenic (having no other identifiable cause) stroke, decompression sickness, migraine, platypnea-orthodeoxia syndrome, and acute limb ischemia secondary to emboli 2.

Data in 1988 revealed that 30% to 40% of young patients who had a cryptogenic stoke had a PFO 1. This percentage compared to 25% in the general population. Since that time, the largest target population studied has been patients of all ages with cryptogenic stroke, in whom the frequency of finding a PFO is often double that of the general population 1. In this population, an optimal secondary prevention strategy is not well defined. Patients with PFO and atrial septal aneurysm who have experienced strokes seem to be at higher risk for recurrent stroke (as high as 15% per year), and secondary preventive strategies are necessary. In another study, 50% of patients with cryptogenic stroke were found to have right-to-left shunting compared to 15% of the controls. Approximately 2/3rds of divers with undeserved (following safe dive profiles) decompression illness, are found to have a PFO. PFOs are especially common in divers with cerebral, inner ear, and cutaneous decompression sickness 3.

PFO primarily increases the risk for stroke from a paradoxical embolism 1. The risk for a cryptogenic stroke is proportional to the size of the PFO. The presence of an interatrial septal aneurysm in combination with a PFO also increases the risk for an adverse event, perhaps because of increased in situ thrombus formation in the aneurysmal tissue or because PFOs associated with an interatrial septal aneurysm tend to be larger. Despite prior reports concerning paradoxical embolism through a PFO, the magnitude of this phenomenon as a risk factor for stroke remains undefined, because deep venous thrombosis (DVT) is infrequently detected in such patients. In one study, pelvic vein thrombi were found more frequently in young patients with cryptogenic stroke than in those with a known cause of stroke. This may provide the source of venous thrombi, particularly when a source of venous thromboembolism (VTE) is not initially identified 4.

By far the most common circumstance prompting the search for PFO is a cryptogenic stroke 1. Although the prevalence of PFO is about 25 percent in the general population, this increases to about 40 to 50 percent in patients who have stroke of unknown cause, referred to as cryptogenic stroke. This is especially true in patients who have had a stroke before age 40.

Finding out whether you have a PFO is not easy, and it’s something that isn’t usually investigated unless a patient is having symptoms like severe migraines, TIA or stroke. In some cases, the PFO combines with another condition, such as atrial fibrillation (AF), to increase the risk of stroke. There are many causes of stroke and having a PFO accounts for only a very small number. PFO is diagnosed with an echocardiogram. An echocardiogram, also called a cardiac echo, creates an image of the heart using ultrasound. A PFO is usually detected by transthoracic echocardiography, transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE), or transcranial Doppler. Transesophageal echocardiogram is the most sensitive test, especially when performed with contrast media injected during a cough or Valsalva maneuver. Patients with cryptogenic strokes should also be evaluated for the presence of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Divers with more than one episode of undeserved decompression illness should undergo evaluation for a right to left shunt. A 2015 diving medicine consensus panel recommended contrasted provocative transthoracic echocardiography for this evaluation, because it has a lower complication rate than transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) and is unlikely to miss a clinically significant PFO 5.

If you know you have a PFO (patent foramen ovale), but don’t have symptoms, you probably won’t have any restrictions on your activities.

If someone has a PFO (patent foramen ovale) that is related to symptoms, they can be treated with aspirin, warfarin or catheter closure, depending on the circumstances. The aim of drug treatment is to prevent a clot from forming in the first place. Nothing will close a PFO (patent foramen ovale) except open-heart surgery or a closure device placed by a catheter threaded from the groin through the veins to the heart. Until recently, there were no approved catheter-closure devices designed for PFOs. The FDA has approved a device for patients who’ve had a stroke believed to be caused by a PFO, which reduces the risk of another stroke.

Studies currently demonstrate low recurrent ischemic stroke rates with medical therapy alone 1. There is some disparity in trials evaluating the superiority of medical and surgical interventions in the prevention of recurrent stroke albeit that risk is apparently low in both approaches. Three randomized clinical trials that totaled more than 2000 patients compared closure of the patent foramen ovale with alternative medical treatment. Data from these trials indicated that PFO offered no benefit compared with medical therapy.

Other studies have shown that patients with cryptogenic stroke and PFO have relatively low outcome rates with medical therapy with or without device closure and that recurrent stroke rates are lower with percutaneously implanted device closure than with medical therapy alone. One study demonstrated that transcatheter closure was found to be superior to medical therapy in the prevention of recurrent neurological events after cryptogenic stroke, and patients taking coumadin had a lower recurrence rate than did those receiving antiplatelet therapy.

Many single-center studies have been published, most have been retrospective, but all have been observational, often with historical controls. The results of these reports have been summarized in meta-analyses supporting the superiority of device closure, frequently with concomitant antiplatelet therapy, versus medical therapy alone. However, prospective studies are lacking.

Figure 1. PFO (Patent Foramen Ovale)

Figure 2. Normal heart blood flow

PFO vs ASD

There are two kinds of holes between the atria (upper chambers of the heart ) of the heart. One is called an atrial septal defect (ASD), and the other is a patent foramen ovale (PFO). Although both are holes in the wall of tissue (septum) between the left and right atrium, their causes are quite different. An ASD is a failure of the septal tissue to form between the atria, and as such it is considered a congenital heart defect, something that you are born with. Generally an ASD hole is larger than that of a PFO. The larger the hole, the more likely there are to be symptoms.

PFOs, on the other hand, can only occur after birth when the foramen ovale fails to close. The foramen ovale is a hole in the wall between the left and right atria of every human fetus. This hole allows blood to bypass the fetal lungs, which cannot work until they are exposed to air. When a newborn enters the world and takes its first breath, the foramen ovale closes, and within a few months it has sealed completely in about 75 percent of us. When it remains open, it is called a patent foramen ovale (PFO), patent meaning open. For the vast majority of the millions of people with a PFO, it is not a problem, even though blood is leaking from the right atrium to the left. Problems can arise when that blood contains a blood clot.

PFO causes

The foramen ovale is a tunnel-like space between the overlying septum secundum and septum primum. The foramen ovale closes in 75% of people at birth when the septum primum and secundum fuse 1. In utero, the foramen ovale is necessary for the flow of blood across the fetal atrial septum. Oxygenated blood from the placenta returns to the inferior vena cava, crosses the foramen ovale, and enters the systemic circulation. In approximately 25% of people, a PFO persists into adulthood. It’s unclear what causes the foramen ovale to stay open in some people, though genetics may play a role.

An overview of normal heart function in a child or adult is helpful in understanding the role of the foramen ovale before birth.

Normal heart function after birth

Your heart has four pumping chambers that circulate your blood:

- The right atrium. The upper right chamber (right atrium) receives oxygen-poor blood from your body and pumps it into the right ventricle through the tricuspid valve.

- The right ventricle. The lower right chamber (right ventricle) pumps the blood through a large vessel called the pulmonary artery and into the lungs, where the blood is resupplied with oxygen and carbon dioxide is removed from the blood. The blood is pumped through the pulmonary valve, which closes when the right ventricle relaxes between beats.

- The left atrium. The upper left chamber (left atrium) receives the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs through the pulmonary veins and pumps it into the left ventricle through the mitral valve.

- The left ventricle. The lower left chamber (left ventricle) pumps the oxygen-rich blood through a large vessel called the aorta and on to the rest of the body. The blood passes through the aortic valve, which also closes when the left ventricle relaxes.

Baby’s heart in the womb

Because a baby in the womb isn’t breathing, the lungs aren’t functioning yet. That means there’s no need to pump blood to the lungs. At this stage, it’s more efficient for blood to bypass the lungs and use a different route to circulate oxygen-rich blood from the mother to the baby’s body.

The umbilical cord delivers oxygen-rich blood to the baby’s right atrium. Most of this blood travels through the foramen ovale and into the left atrium. From there the blood goes to the left ventricle, which pumps it throughout the body. Blood also travels from the right atrium to the right ventricle, which also pumps blood to the body via another bypass system.

Newborn baby’s heart

When a baby’s lungs begin functioning, the circulation of blood through the heart changes. Now the oxygen-rich blood comes from the lungs and enters the left atrium. At this point, blood circulation follows the normal circulatory route.

The pressure of the blood pumping through the heart usually forces the flap opening of the foramen ovale closed. In most people, the opening fuses shut, usually sometime during infancy.

PFO symptoms

Most people with a PFO (patent foramen ovale) don’t know they have it, because it’s usually a hidden condition that doesn’t create signs or symptoms.

PFO complications

PFOs may be associated with atrial septal aneurysms (a redundancy of the interatrial septum), Eustachian valves (a remnant of the sinus venosus valve), and Chiari networks (filamentous strands in the right atrium) 1. PFOs may serve as either a conduit for paradoxical embolization from the venous side to the systemic circulation or, because of their tunnel-like structure and propensity for stagnant flow, may serve as a nidus for in situ thrombus formation 5.

Generally, a PFO (patent foramen ovale) doesn’t cause complications. But some studies have found the disorder is more common in people with certain conditions, such as unexplained strokes and migraines with aura. PFOs don’t actually cause strokes, but they provide a portal through which a thrombus might pass from the right to the left side of the circulation.

In most cases, there are other reasons for these neurologic conditions, and it’s just a coincidence the person also has a PFO (patent foramen ovale). However, in some cases, small blood clots in the heart may move through a PFO (patent foramen ovale), travel to the brain and cause a stroke.

The possible link between a PFO (patent foramen ovale) and a stroke or migraine is controversial, and research studies are ongoing.

In rare cases a PFO (patent foramen ovale) can cause a significant amount of blood to bypass the lungs, resulting in low blood oxygen levels (hypoxemia).

In decompression illness, which can occur in scuba diving, an air blood clot can travel through a PFO (patent foramen ovale).

In some cases, other heart defects may be present in addition to a PFO (patent foramen ovale).

PFO diagnosis

A doctor trained in heart conditions (cardiologist) may order one or more of the following tests to diagnose a patent foramen ovale:

Echocardiogram

An echocardiogram shows the anatomy, structure and function of your heart.

A common type of echocardiogram is called a transthoracic echocardiogram. In this test, sound waves directed at your heart from a wandlike device (transducer) held on your chest produce video images of your heart in motion. Doctors may use this test to diagnose a patent foramen ovale and detect other heart problems.

Variations of this procedure may be used to identify patent foramen ovale, including:

- Color flow Doppler. When sound waves bounce off blood cells moving through your heart, they change pitch. These characteristic changes (Doppler signals) and computerized colorization of these signals can help your doctor examine the speed and direction of blood flow in your heart. If you have a patent foramen ovale, a color flow Doppler echocardiogram could detect the flow of blood between the right atrium and left atrium.

- Saline contrast study (bubble study). With this approach, a sterile salt solution is shaken until tiny bubbles form and then is injected into a vein. The bubbles travel to the right side of your heart and appear on the echocardiogram. If there’s no hole between the left atrium and right atrium, the bubbles will simply be filtered out in the lungs. If you have a PFO (patent foramen ovale), some bubbles will appear on the left side of the heart. The presence of a PFO may be difficult to confirm by a transthoracic echocardiogram.

Transesophageal echocardiogram

Doctors may conduct another type of echocardiogram called a transesophageal echocardiogram to get a closer look at the heart and blood flow through the heart. In this test, a small transducer attached to the end of a tube is inserted down the tube leading from your mouth to your stomach (esophagus).

This is generally the most accurate available test for doctors to see a PFO (patent foramen ovale) by using the ultrasound in combination with color flow Doppler or a saline contrast study.

Other tests

Your doctor may recommend additional tests if you’re diagnosed with a PFO (patent foramen ovale) and you have had a stroke. Your doctor may also refer you to a doctor trained in brain and nervous system conditions (neurologist).

PFO treatment

Most people with a PFO don’t need treatment. In certain circumstances, however, your doctor may recommend that you or your child have a procedure to close the PFO.

Treatment is aimed at prevention of a secondary event primarily with antiplatelet or anticoagulation therapy or atrial septal device closure. The risk associated with either treatment is low overall, and superiority of one therapy over the other is still contested. Accepted device closure treatment is for large PFOs (greater than 25 mm), and in patients with PFOs who have already had a recurrent neurological event. Any identified venous thromboembolic event involving PFO should be treated with anticoagulation, just as pulmonary embolism would be treated 3.

Reasons for closure

If a PFO is found when an echocardiogram is done for other reasons, a procedure to close the opening usually isn’t performed. Procedures to close the patent foramen ovale may be done in certain circumstances, such as to treat low blood oxygen levels linked to the patent foramen ovale.

Closure of a patent foramen ovale to prevent migraines isn’t currently recommended. Closure of a patent foramen ovale to prevent a stroke remains controversial.

In some cases, doctors may recommend closure of the patent foramen ovale in individuals who have had recurrent strokes despite medical therapy, when no other cause has been found.

PFO repair

Procedures to close a patent foramen ovale include:

Device closure

Using cardiac catheterization, doctors can insert a device that plugs the PFO. In this procedure, the device is on the end of a long flexible tube (catheter).

The doctor inserts the device-tipped catheter into a vein in the groin and guides the device into place with the imaging assistance of an echocardiogram.

Device closure is safe and seems to be effective, with a stroke recurrence rate of between 0% and 3.8% per year 1. The functional closure is usually followed by permanent fusion of the 2 flaps comprising the defective atrial septum. Complete closure occurs in up to 80%, and in an additional 10% to 15% the residual right-to-left shunting appears to be trivial 1.

Although complications are uncommon with the device closure procedure, a tear of the heart or blood vessels, dislodgement of the device, or the development of irregular heartbeats may occur. Atrial arrhythmias may occur in 3% to 5% but are transient. Although the rate of development of atrial fibrillation has been 5% to 6% with some devices, they have also been associated with thrombus formation on the device. Late cardiac perforation has been reported with some devices but appears to be rare. In comparisons, atrial fibrillation was more common among closure patients than anticoagulated patients in secondary preventive strategies 6.

Intraprocedural complications utilizing device closure include perforation resulting in tamponade, air embolism, device embolization, and stroke 1. However, these are all rare events in experienced hands, with rates of less than 1% 1.

PFO surgery

A surgeon can close the patent foramen ovale by opening up the heart and stitching shut the flap-like opening. This procedure can be conducted using a very small incision and may be performed using robotic techniques.

If you or your child is undergoing surgery to correct another heart problem, your doctor may recommend that you have the PFO corrected surgically at the same time. Research is ongoing to determine the benefits of closing the PFO during heart surgery to correct another problem.

Stroke prevention

PFO has been identified as the major contributing factor in cryptogenic stroke in 50% of affected young adults and is present in 25% of the general adult population.

Medications can be used to try to reduce the risk of blood clots crossing a PFO (patent foramen ovale). Antiplatelet therapy such as aspirin or clopidogrel (Plavix) and other blood thinning medications (anticoagulants) — such as warfarin (Coumadin, Jantoven), dabigatran (Pradaxa), apixaban (Eliquis) and rivaroxaban (Xarelto) — may be helpful for people with a patent foramen ovale who’ve had a stroke.

It’s not clear whether medications or procedures to close the defect are most appropriate for stroke prevention in people with a PFO (patent foramen ovale). Studies are ongoing to answer this question.

If you’ll be traveling long distances, it’s important to follow recommendations for preventing blood clots. If you’re traveling by car, stop periodically and go for a short walk. On an airplane, be sure to stay well-hydrated and walk around whenever it’s safe to do so.

- Hampton T, Murphy-Lavoie HM. Patent Foramen Ovale. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK493151[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Pristipino C, Sievert H, D’Ascenzo F, Louis Mas J, Meier B, Scacciatella P, Hildick-Smith D, Gaita F, Toni D, Kyrle P, Thomson J, Derumeaux G, Onorato E, Sibbing D, Germonpré P, Berti S, Chessa M, Bedogni F, Dudek D, Hornung M, Zamorano J., Evidence Synthesis Team. Eapci Scientific Documents and Initiatives Committee. International Experts. European position paper on the management of patients with patent foramen ovale. General approach and left circulation thromboembolism. Eur. Heart J. 2018 Oct 25[↩]

- Kerut EK, Truax WD, Borreson TE, Van Meter KW, Given MB, Giles TD. Detection of right to left shunts in decompression sickness in divers. Am. J. Cardiol. 1997 Feb 01;79(3):377-8.[↩][↩]

- Zoltowska DM, Thind G, Agrawal Y, Gupta V, Kalavakunta JK. May-Thurner Syndrome as a Rare Cause of Paradoxical Embolism in a Patient with Patent Foramen Ovale. Case Rep Cardiol. 2018;2018:3625401.[↩]

- Smart D, Mitchell S, Wilmshurst P, Turner M, Banham N. Joint position statement on persistent foramen ovale (PFO) and diving. South Pacific Underwater Medicine Society (SPUMS) and the United Kingdom Sports Diving Medical Committee (UKSDMC). Diving Hyperb Med. 2015 Jun;45(2):129-31.[↩][↩]

- Giordano M, Gaio G, Santoro G, Palladino MT, Sarubbi B, Golino P, Russo MG. Patent foramen ovale with complex anatomy: Comparison of two different devices (Amplatzer Septal Occluder device and Amplatzer PFO Occluder device 30/35). Int. J. Cardiol. 2018 Oct 16[↩]