What is pigmented purpuric dermatosis

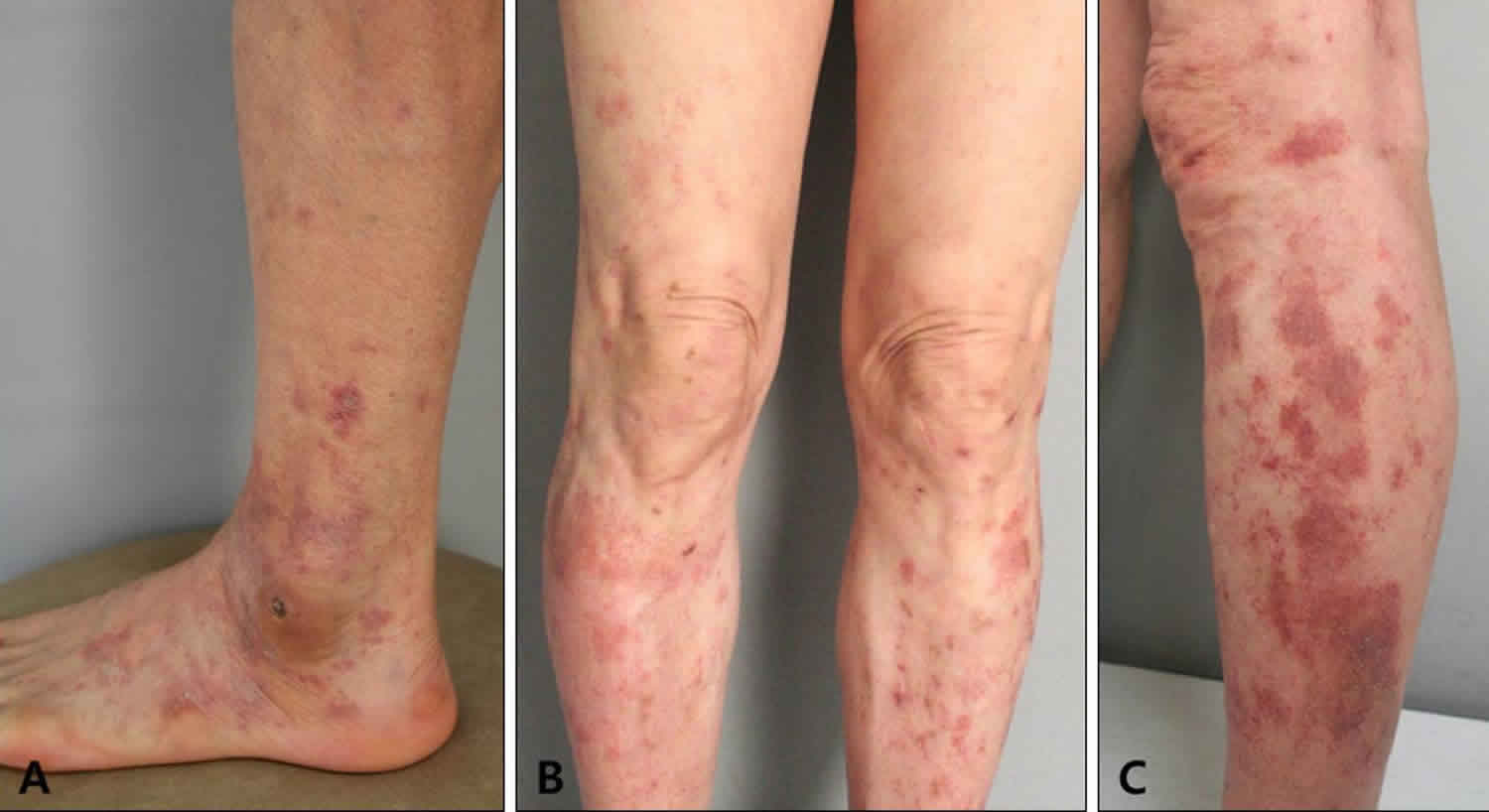

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis is a group of chronic skin diseases of mostly unknown cause characterized by a distinct purpuric rash, often confined to the lower limbs 1. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are characterized by extravasation of red blood cells in the skin with marked hemosiderin deposition 2. Five different clinical types of pigmented purpuric dermatosis have been described, with different clinical appearances, but similar histopathology. They are: progressive pigmented purpuric dermatosis or Schamberg disease, purpura annularis telangiectodes or Majocchi’s disease, lichen aureus, pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatosis, and eczematid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis 3. Several other types have also been reported, but they are rare, such as linear, granulomatous, quadrantic, transitory, and familial forms 2. Schamberg disease may occur in persons of any age. Itching purpura and the dermatosis of Gougerot and Blum mainly affect middle-aged men. Lichen aureus and Majocchi disease are predominantly diseases of children or young adults 4.

In Schamberg disease, irregular plaques and patches of orange-brown pigmentation develop on the lower limbs. The lesions are chronic and persist for years. With time, many of the lesions tend to extend and may become darker brown in color, but some may spontaneously clear.

In itching purpura, the lesions are much more extensive, and patients typically complain of severe pruritus.

The hallmark of a pigmented purpuric dermatosis is its characteristic orange-brown, speckled, cayenne pepper–like discoloration. The lower limbs are affected in Schamberg disease, whereas itching purpura is characterized by more generalized skin involvement.

In lichen aureus, the eruption is usually a solitary lesion or a localized group of golden brown lesions that may affect any part of the body; however, the leg is the most commonly affected area. Linear or segmental forms of lichen aureus have been reported.

Majocchi disease is characterized by small annular plaques of purpura that contain prominent telangiectasias.

Pigmented purpura with lichenoid-type skin change is yet another clinical variant, which Gougerot and Blum first reported. Lesions appear similar to those of Schamberg disease in association with red-brown lichenoid papules.

Pigmented purpuric dermatoses are rare. There is not a racial predilection; although, they appear slightly more often in males. Children can also be affected 5.

Most cases of pigmented purpuric dermatosis are idiopathic 6. It is important to recognize that these disorders are not associated with coagulopathies or thrombocytopenia. However, since most cases present on the lower extremities, important underlying factors include venous stasis, exercise, and capillary fragility which lead to erythrocyte extravasation into the dermis and the characteristic purpuric color 5. Due to inflammatory infiltrate of lymphocytes, macrophages, and Langerhans cells which is often seen on skin biopsies as a capillaritis, cell-mediated immunity is also implicated in the pathogenesis of these disorders and may contribute to vascular fragility. Immunohistochemical studies of Schamberg disease, a subtype of pigmented purpuric dermatosis, have revealed a perivascular infiltrate of dendritic cells and lymphocytes which interact with vascular endothelial cells and affect the permeability of the microvasculature 7. Humoral immunity also may be involved in the pathogenesis as immunoglobulin and complement deposition around dermal vessels has been observed in some cases 8. Many medications also have been reported as causing pigmented purpuric dermatosis including acetaminophen, aspirin, carbamazepine, chlordiazepoxide, diltiazem, dipyridamole, furosemide, glipizide, hydralazine, infliximab, interferon-alpha, medroxyprogesterone acetate, meprobamate, pseudoephedrine, raloxifene, and thiamine 9.

The diagnosis and management of pigmented purpuric dermatosis is difficult and is best done with a multidisciplinary team that includes the primary care provider, dermatologist, nurse practitioner and pathologist. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis remains an enigma and a therapeutic challenge 1. Pigmented purpuric dermatosis is often chronic with a relapsing and remitting course. However, it is a benign, often asymptomatic condition. Even if the capillaritis improves and the active inflammation ceases, the resulting hemosiderin deposition in the dermis can take months to years to slowly fade. Patients should be encouraged to wear compression stockings and keep the legs elevated at rest. The use of moisturizers may help relieve the itching. For most patients, the problem is poor cosmesis.

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis causes

The cause of pigmented purpuric dermatosis is unknown (idiopathic). Rare familial cases of Schamberg disease and Majocchi disease have been reported in the literature, implying a genetic cause in a minority of patients. Venous hypertension, exercise , gravitational dependency, capillary fragility, focal infections, and chemical ingestion are important cofactors 2. Specific drugs are suspected to induce pigmented purpuric dermatosis, including: acetaminophen, aspirin, adalin, carbromal, chlordiazepoxide, glipizide, glybuzole, hydralazine, meprobamate, persantin, reserpine, thiamine, interferon alpha, and medroxyprogesterone acetate injection 2. The differential diagnosis of pigmented purpuric dermatosis includes hyperglobulinaemic purpura, early mycosis fungoides, purpuric clothing dermatitis, stasis pigmentation, scurvy, leukocytoclastic vasculitis, and drug hypersensitivity reactions 2.

Histologically, a perivascular T-cell lymphocytic infiltrate is centered on the superficial small blood vessels of the skin, which show signs of endothelial cell swelling and narrowing of the lumen. Extravasation of red blood cells with marked hemosiderin deposition in macrophages is also found, and a rare granulomatous variant of chronic pigmented dermatosis has been reported 10.

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis pathophysiology

In pigmented purpuric dermatoses, capillaritis in the dermis with possible concomitant venous hypertension leads to endothelial cell dysfunction and extravasation of red blood cells. These erythrocytes deposit in the dermis, clinically manifesting as purpuric macules and patches with variable configurations. Over time, as the hemosiderin is resorbed, golden-brown pigmentation collects in the skin, which over time resolves. However, the disease can often flare and persist chronically.

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis symptoms

There are many different subtypes of pigmented purpuric dermatosis. Their clinical presentation can mainly distinguish these, but some have unique histopathology as well.

Progressive Pigmentary Dermatosis (Schamberg Disease)

This condition presents as an eruption on the legs that consists of red-brown macules and patches with pinpoint red puncta. These stippled puncta have been likened to grains of cayenne pepper as the skin lesions can often have orange-brown color due to hemosiderin deposition. Although initially described in adolescents, it can affect all ages and on average presents in the fifth decade of life 11. The condition is most often asymptomatic although mild pruritus can occur. The eruption is most common on the lower legs but can occur on the trunk or arms. A chronic relapsing and remitting course can happen over time.

Purpura Aannularis Telangiectodes of Majocchi

This pigmented purpuric dermatosis variant presents with annular patches of punctate red-brown macules and patches on the legs with punctate petechiae at the border. The annular (ring-like) configuration of the patches with central clearing is unique, and annular plaques also can manifest. This eruption typically begins on the lower legs but can spread proximally and may also occur on the arms and trunk. This subtype is most common in females 12.

Lichen Aureus

The hallmark of lichen aureus is the presentation of ovoid golden orange to mildly purpuric macules, patches and plaques. They may be quite pruritic although are often asymptomatic. The lesions are often unilateral and localized to the legs but can involve the trunk and arms. It is most common in young adults and can have a chronic course which may persist for years. This eruption is also distinguished by a dense band of lichenoid dermal inflammation, in contrast to the other subtypes of pigmented purpuric dermatosis, which do not exhibit lichenoid histopathology 13.

Pigmented Purpuric Lichenoid Dermatitis of Gougerot and Blum

This eruption is distinguished by red-brown to purpuric ovoid papules and plaques that occur on the lower extremities. Although it is named as lichenoid dermatitis, it does not typically exhibit lichenoid histology. Clinically, this condition can mimic Kaposi sarcoma, and therefore, skin biopsies are helpful to make an accurate diagnosis 14. This subtype is more common in males and can be pruritic.

Eczematoid-Like Purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis

This condition is characterized by mild scale overlying purpuric and petechial macules, papules and patches. It is often pruritic and the lesions can be extensive and may involve the trunk and arms in addition to the lower extremities. It typically self-resolves over many months 15.

Disseminated Pruriginous Angiodermatitis (Itching Purpura)

Itching purpura presents acutely on the legs with diffuse purpuric, orange to brown macules and patches, accompanied by severe pruritus. It can evolve to become widespread and often has a chronic course. It is most common in middle-aged men 16.

Unilateral Linear Capillaritis (Linear Pigmented Purpura)

This eruption presents as a linear distribution of purpuric to red-brown macules that are unilateral on a lower extremity. It commonly self-resolves. Unilateral linear capillaritis has been reported as a segmental variant of Schamberg disease or lichen aureus 17.

Granulomatous Pigmented Purpura

This subtype of pigmented purpuric dermatosis has been most often reported in patients of Asian descent. It occurs as red-brown macules, papules, and plaques on the feet and ankles but can occur on the hands and wrists. It is distinguished by dense granulomatous inflammation in the dermis with thickened capillaries and hemosiderin deposition 18.

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis diagnosis

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis are largely diagnosed based on the clinical presentation. However, with atypical presentations or to rule out cutaneous vasculitis, dermatitis, or cutaneous t-cell lymphoma, skin biopsy by punch technique can be helpful. Skin biopsies show perivascular lymphohistiocytic inflammation around small cutaneous blood vessels with endothelial cell swelling. Leukocytoclastic vasculitis is not observed 19. Extravasated erythrocytes are often seen in the dermis with variable hemosiderin deposition in macrophages. The hemosiderin tends to occur in the superficial papillary dermis, in contrast to stasis dermatitis, in which the deposition occurs around deeper blood vessels. Mild dermatitis can be seen in the overlying epidermis, manifesting as mild spongiosis with lymphocyte exocytosis. Dermatitis is most pronounced in the pigmented purpuric dermatosis variants pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis of Gougerot and Blum and the eczematoid-like purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis. In contrast, in the lichen aureus variant of pigmented purpuric dermatosis, there is a band of lichenoid lymphocytic inflammation at the dermal-epidermal junction, with a Grenz zone of uninvolved papillary dermis 20. A rare variant of pigmented purpuric dermatosis has also been reported in which granulomatous inflammation was characteristic 21.

Laboratory investigations are unremarkable in pigmented purpuric dermatosis. A full blood count and peripheral blood smear are necessary to exclude thrombocytopenia. A coagulation screen, bleeding time, platelet aggregation, capillary test excludes other possible causes of purpura, and tests for, antinuclear antibodies (ANA), rheumatoid factor, anti-HBsAg antibody and anti-HCV antibody should also be performed for excluding rheumatologic diseases and viral infections 22.

Dermatoscopy is a non-invasive, diagnostic technique that allows the visualisation of morphological features invisible to the naked eye; it combines a method that renders the corneal layer of the skin translucent with an optical system that magnifies the image projected onto the retina 23. Dermatoscopy has become a routine technique in dermatological practice in the last decade and has contributed to our improved knowledge of the morphology of numerous cutaneous lesions.

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis treatment

It can be challenging to treat pigmented purpuric dermatoses. If a medication reaction is causative, the eruption should clear with discontinuation of the drug. Due to the possible cause of vascular hypertension and venous stasis of the lower extremities, compression stockings are recommended. A study of 3 patients with pigmented purpuric dermatosis revealed clearance of this eruption after 4 weeks of treatment with the bioflavonoid, rutoside 50 mg 2 times per day, and ascorbic acid 500 mg 2 times per day 24. Given the safety of these supplements, this is a reasonable first-line treatment. Anecdotal data exist for calcineurin-inhibitors, colchicine, pentoxifylline, immunosuppressants, ultraviolet therapy, and laser therapy 25.

Itch (pruritus) may be alleviated by the use of topical corticosteroids and antihistamines.

Tamaki et al reported successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatoses using griseofulvin 26. Treatment with oral cyclosporin has also been successful 27.

The use of narrowband UVB and psoralen plus UVA have shown to be effective treatments for some patients with pigmented purpuric dermatoses 28.

Medium to high potency topical corticosteroids such as triamcinolone can also be used and may improve pruritus and the inflammatory component of this condition. Although systemic immunosuppression with corticosteroids or cyclosporine can be helpful, the side effect profile of these medications and the benign nature of pigmented purpuric dermatosis may not warrant their use 29. However, the condition often recurs when immunosuppression is discontinued. Topical tacrolimus or pimecrolimus can be helpful for chronic use to limit the risk of cutaneous atrophy from topical corticosteroids 30. Griseofulvin 500 mg to 750 mg daily improved 6 patients with pigmented purpuric dermatosis 31. Other case reports of patients with pigmented purpuric dermatosis showed improvement with colchicine 0.5 mg 2 times per day, minocycline, methotrexate, and pentoxifylline 400 mg 3 times per day 32. Ultraviolet (UV) light therapy with PUVA or narrowband UVB also has been reported to be beneficial 33. In some cases, the disease flared with discontinuation of treatment, but in others, sustained remission was achieved 34. Topical photodynamic therapy using 5-aminolevulinic acid or methyl aminolevulinic acid as photosensitizing agents also has been reported to improve pigmented purpuric dermatosis 35.

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis prognosis

Pigmented purpuric dermatosis is often chronic with a relapsing and remitting course. Most eventually resolve spontaneously 4. Typically, pigmented purpuric dermatosis is asymptomatic, but itch may sometimes be a prominent feature in some cases, especially in patients with itching purpura or eczematidlike purpura of Doucas and Kapetanakis. These diseases have no systemic findings. Even if the capillaritis improves and the active inflammation ceases, the resulting hemosiderin deposition in the dermis can take months to years to slowly fade.

- Kim DH, Seo SH, Ahn HH, Kye YC, Choi JE. Characteristics and Clinical Manifestations of Pigmented Purpuric Dermatosis. Ann Dermatol. 2015;27(4):404–410. doi:10.5021/ad.2015.27.4.404 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4530150[↩][↩]

- Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Int J Dermatol. 2004 Jul; 43(7):482-8.[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Ozkaya DB, Emiroglu N, Su O, et al. Dermatoscopic findings of pigmented purpuric dermatosis. An Bras Dermatol. 2016;91(5):584–587. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20165124 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5087214[↩]

- Pigmented purpuric dermatosis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1084594-overview[↩][↩]

- Tristani-Firouzi P, Meadows KP, Vanderhooft S. Pigmented purpuric eruptions of childhood: a series of cases and review of literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001 Jul-Aug;18(4):299-304.[↩][↩]

- Tolaymat L, Hall MR. Pigmented Purpuric Dermatitis. [Updated 2019 Mar 14]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519562[↩]

- von den Driesch P, Simon M. Cellular adhesion antigen modulation in purpura pigmentosa chronica. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1994 Feb;30(2 Pt 1):193-200.[↩]

- Gupta G, Holmes SC, Spence E, Mills PR. Capillaritis associated with interferon-alfa treatment of chronic hepatitis C infection. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2000 Nov;43(5 Pt 2):937-8.[↩]

- Sardana K, Sarkar R, Sehgal VN. Pigmented purpuric dermatoses: an overview. Int. J. Dermatol. 2004 Jul;43(7):482-8.[↩]

- García-Rodiño S, Rodríguez-Granados MT, Seoane-Pose MJ, Espasandín-Arias M, Barbeito-Castiñeiras G, Suárez-Peñaranda JM, et al. Granulomatous variant of pigmented purpuric dermatosis: report of two cases and review of the literature. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2017 Apr 18.[↩]

- Torrelo A, Requena C, Mediero IG, Zambrano A. Schamberg’s purpura in children: a review of 13 cases. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2003 Jan;48(1):31-3.[↩]

- Newton RC, Raimer SS. Pigmented purpuric eruptions. Dermatol Clin. 1985 Jan;3(1):165-9.[↩]

- Price ML, Jones EW, Calnan CD, MacDonald DM. Lichen aureus: a localized persistent form of pigmented purpuric dermatitis. Br. J. Dermatol. 1985 Mar;112(3):307-14.[↩]

- Wong RC, Solomon AR, Field SI, Anderson TF. Pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis of Gougerot-Blum mimicking Kaposi’s sarcoma. Cutis. 1983 Apr;31(4):406-8, 410[↩]

- DOUCAS C, KAPETANAKIS J. Eczematid-like purpura. Dermatologica. 1953;106(2):86-95.[↩]

- Pravda DJ, Moynihan GD. Itching purpura. Cutis. 1980 Feb;25(2):147-51.[↩]

- Riordan CA, Darley C, Markey AC, Murphy G, Wilkinson JD. Unilateral linear capillaritis. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 1992 May;17(3):182-5.[↩]

- Lin WL, Kuo TT, Shih PY, Lin WC, Wong WR, Hong HS. Granulomatous variant of chronic pigmented purpuric dermatoses: report of four new cases and an association with hyperlipidaemia. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2007 Sep;32(5):513-5.[↩]

- Smoller BR, Kamel OW. Pigmented purpuric eruptions: immunopathologic studies supportive of a common immunophenotype. J. Cutan. Pathol. 1991 Dec;18(6):423-7.[↩]

- Rudolph RI. Lichen aureus. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1983 May;8(5):722-4.[↩]

- Saito R, Matsuoka Y. Granulomatous pigmented purpuric dermatosis. J. Dermatol. 1996 Aug;23(8):551-5.[↩]

- Pigmented purpura dermatosis and viral hepatitis: a case-control study. Ehsani AH, Ghodsi SZ, Nourmohammad-Pour P, Aghazadeh N, Damavandi MR. Australas J Dermatol. 2013 Aug; 54(3):225-7.[↩]

- [Vascular patterns in dermoscopy]. Martín JM, Bella-Navarro R, Jordá E. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2012 Jun; 103(5):357-75.[↩]

- Reinhold U, Seiter S, Ugurel S, Tilgen W. Treatment of progressive pigmented purpura with oral bioflavonoids and ascorbic acid: an open pilot study in 3 patients. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 1999 Aug;41(2 Pt 1):207-8.[↩]

- Plachouri KM, Florou V, Georgiou S. Therapeutic strategies for pigmented purpuric dermatoses: a systematic literature review. J Dermatolog Treat. 2018 May 18. 1-5.[↩]

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, et al. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br J Dermatol. 1995 Jan. 132(1):159-60.[↩]

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br J Dermatol. 1996 Jan. 134(1):180-1.[↩]

- Dhali TK, Chahar M, Haroon MA. Phototherapy as an effective treatment for Majocchi’s disease–case report. An Bras Dermatol. 2015 Jan-Feb. 90 (1):96-9.[↩]

- Okada K, Ishikawa O, Miyachi Y. Purpura pigmentosa chronica successfully treated with oral cyclosporin A. Br. J. Dermatol. 1996 Jan;134(1):180-1.[↩]

- Böhm M, Bonsmann G, Luger TA. Resolution of lichen aureus in a 10-year-old child after topical pimecrolimus. Br. J. Dermatol. 2004 Aug;151(2):519-20.[↩]

- Tamaki K, Yasaka N, Osada A, Shibagaki N, Furue M. Successful treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with griseofulvin. Br. J. Dermatol. 1995 Jan;132(1):159-60.[↩]

- Hoesly FJ, Huerter CJ, Shehan JM. Purpura annularis telangiectodes of Majocchi: case report and review of the literature. Int. J. Dermatol. 2009 Oct;48(10):1129-33.[↩]

- Gudi VS, White MI. Progressive pigmented purpura (Schamberg’s disease) responding to TL01 ultraviolet B therapy. Clin. Exp. Dermatol. 2004 Nov;29(6):683-4.[↩]

- Kocaturk E, Kavala M, Zindanci I, Zemheri E, Sarigul S, Sudogan S. Narrowband UVB treatment of pigmented purpuric lichenoid dermatitis (Gougerot-Blum). Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2009 Feb;25(1):55-6.[↩]

- Kim SK, Kim EH, Kim YC. Treatment of pigmented purpuric dermatosis with topical photodynamic therapy. Dermatology (Basel). 2009;219(2):184-6.[↩]