Poliomyelitis

Poliomyelitis also known as polio, is a highly contagious viral infection caused by the poliovirus that attacks your nervous system resulting in paralysis and muscle spasms, and in some cases encephalitis 1, 2. In serious polio cases, it can cause paralysis where you can’t move parts of the body. The paralysis may be lifelong and can sometimes be life-threatening causing death due to breathing muscle paralysis. Because of the polio vaccines, United States is now polio-free, but vaccination with the polio vaccine (inactivated poliovirus vaccine [IPV]) is still important to prevent cases of polio from coming back. Furthermore, polio still occur in some parts of the world, such as Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan, and there are records of imported cases in some African countries 3. As long as a single child remains infected, children in all countries are at risk of contracting polio 3. Failure to eradicate polio from these last remaining countries could result in a global resurgence of the disease 3.

The poliovirus only infects humans and spreads from person to person. Polio (poliomyelitis) mainly affects children under 5 years of age, although anyone can get polio 3. The polio virus lives in an infected person’s throat and intestines. It enters the body through the mouth and spreads through contact with the feces (poop) of an infected person and, though less common, through droplets from a sneeze or cough. You can get infected with poliovirus if you have feces on your hands and you touch your mouth. Also, you can get infected if you put in your mouth objects like toys that are contaminated with feces (poop).

An infected person may spread the virus to others immediately before and about 1 to 2 weeks after symptoms appear. The polio virus can live in an infected person’s feces for many weeks. It can contaminate food and water in unsanitary conditions.

People who don’t have symptoms can still pass the polio virus to others and make them sick.

About 1 in 200 infections leads to irreversible paralysis. Among those paralyzed, 5–10% die when their breathing muscles become immobilized.

Poliovirus

Poliovirus is a member of the enterovirus subgroup, family Picornaviridae 4. Enteroviruses are transient inhabitants of the gastrointestinal tract and are stable at acidic pH. Picornaviruses are small, ether-insensitive viruses with an RNA genome. Poliovirus is highly contagious and causes polio, or poliomyelitis, a serious and debilitating disease.

There are three poliovirus serotypes (PV1, PV2, and PV3) with minimal heterotypic immunity between them. That is, immunity to one serotype does not produce significant immunity to the other serotypes.

Poliovirus is rapidly inactivated by heat, formaldehyde, chlorine, and ultraviolet light.

The naturally-occurring poliovirus, called the wild-type poliovirus (WPV), has been eliminated in most countries and causes few cases of polio. Another version of the virus, called the vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV), is more widespread and now causes most infections worldwide. Vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) exists mainly in a few countries that use an oral vaccine with a weakened poliovirus (OPV).

The weakened virus in the oral vaccine (OPV) doesn’t itself cause polio, and vaccinated people rarely contract VDPV (vaccine-derived poliovirus). Instead, vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) is a new version of the virus that develops within a community or region where not enough people are vaccinated.

Even though the weakened virus in the oral vaccine (OPV) doesn’t cause illness, it can spread. If most people in a community are vaccinated, the spread of the weakened virus is controlled. If many people aren’t vaccinated, the weakened virus can move through a community for a long time. This gives the virus the chance to change, or mutate, and behave like the wild-type virus that causes illness.

Infections from vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) have been reported in the United States. In each case, the person was either not vaccinated or had a significantly weakened immune system. One case in New York in July 2022 was in a county with a lower-than-average polio vaccination rate 5. Samples from wastewater showed that vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) was spreading in some communities.

Since 2000, polio vaccination in the United States has used an injected vaccine with an inactivated poliovirus (IPV) that doesn’t create the risk for vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) 6. Inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) is given by shot in the arm or leg, depending on the person’s age.

The poliovirus only infects humans. Poliovirus is very contagious and spreads through person-to-person contact.

The poliovirus spreads through contact with:

- The stool (poop) of person who has the infection

- Droplets from a sneeze or cough of someone who has the infection

This contact can happen if:

- You get contaminated stool or droplets on your hands and then touch your mouth

- A child puts contaminated toys or other objects into their mouth

- You share food or utensils with someone who has the infection

People who have poliovirus infection can spread it to others just before and up to several weeks after the symptoms appear. People who don’t have symptoms can still spread poliovirus to others and make them sick.

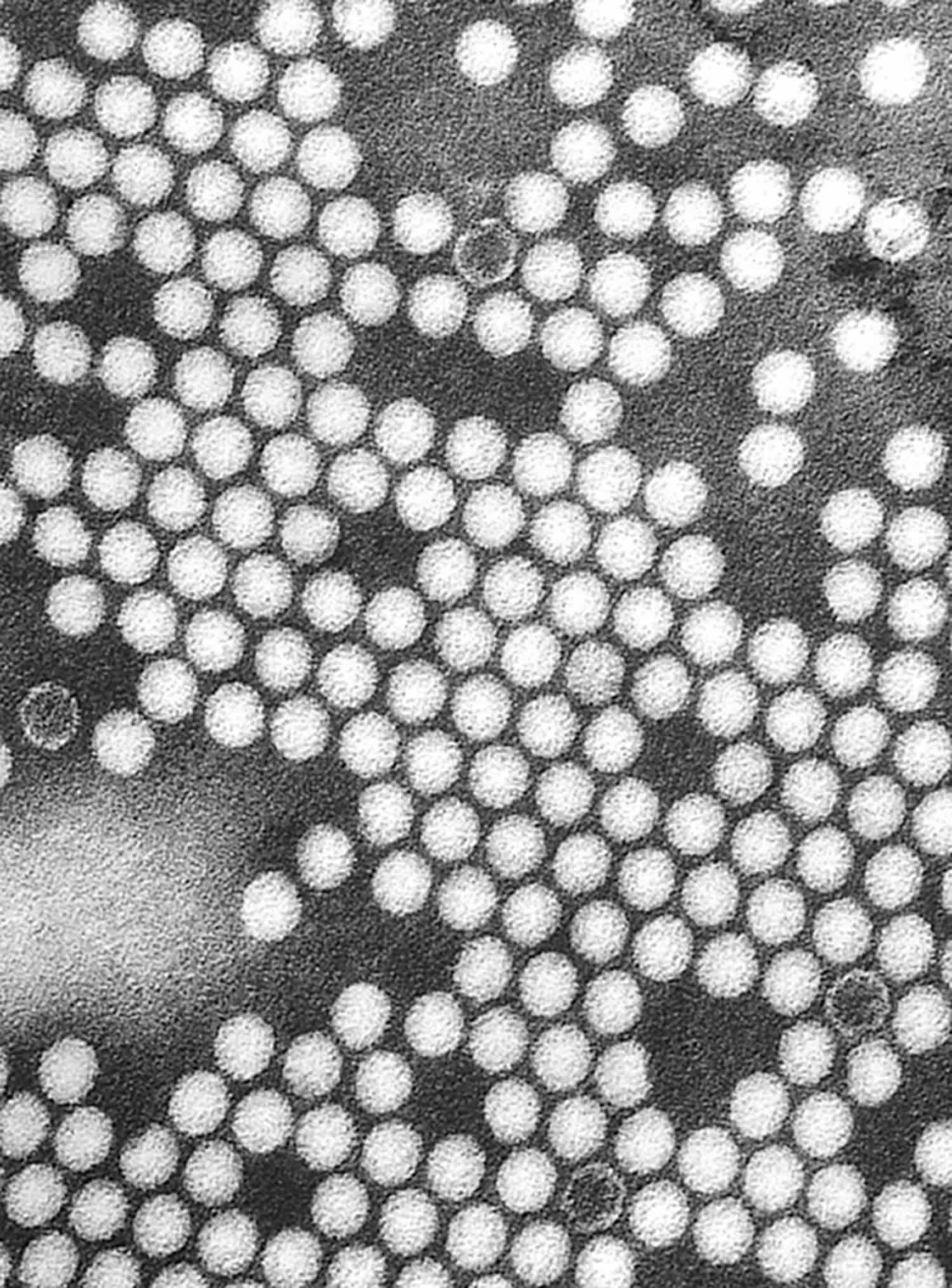

Figure 1. Poliovirus

Footnote: A transmission electron micrograph shows the 30 nm poliovirus particles

How is polio spread?

Poliovirus only infects humans. Poliovirus is very contagious and spreads through person-to-person contact. The virus lives in an infected person’s throat and intestines. It enters the body through the mouth and spreads through contact with the feces (poop) of an infected person and, though less common, through droplets from a sneeze or cough. You can get infected with poliovirus if you have feces on your hands and you touch your mouth. Also, you can get infected if you put in your mouth objects like toys that are contaminated with feces (poop).

An infected person may spread the virus to others immediately before and about 1 to 2 weeks after symptoms appear. The virus can live in an infected person’s feces for many weeks. It can contaminate food and water in unsanitary conditions.

People who don’t have symptoms can still pass the virus to others and make them sick.

Who is at risk from polio?

Polio has been eradicated in most parts of the world, although there are still a few cases in Afghanistan, Nigeria, Pakistan and African countries 3. People who are not immune to the polio virus may become infected if they travel to areas with polio. They may also take the infection with them to polio-free countries, including United States, and could potentially infect others.

Children under 5 and young adults are most at risk, although anyone can get polio.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) publishes travel notices of countries where there is a higher risk of polio. Countries at a higher risk of polio are generally in Africa, the Middle East, and southern and central Asia. For additional information on the status of polio eradication efforts, countries or areas with active wild poliovirus (WPV) or vaccine–derived polioviruses (VDPV) circulation, and vaccine recommendations, consult the travel notices on the CDC Travelers’ Health website (https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel) and the Global Polio Eradication Initiative website (https://polioeradication.org).

If you plan to travel to an area where polio occurs, or care for people with polio, ask your doctor about precautions. Even if you have been vaccinated, you may need a booster dose to ensure you are immune.

Vaccinated adults who plan to travel to an area where polio is spreading should get a booster dose of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV). Immunity after a booster lasts a lifetime.

Polio causes

Polio is caused by the poliovirus. The poliovirus can be transmitted through direct contact with someone infected with the virus or, less commonly, through contaminated food and water. Transmission occurs from person to person through the oral and fecal–oral routes. The poliovirus enters through the mouth and multiplies in the throat and gastrointestinal tract. People carrying the poliovirus can spread the virus for 1–2 weeks in nasopharyngeal secretions and for 3–6 weeks in their feces. People who have the virus but don’t have symptoms can pass the virus to others.

The poliovirus mainly targets nerve cells in the spinal cord and brain stem that control muscle movement. Nerve cells controlling sensation are generally not affected.

Risk factors for poliomyelitis

Polio mainly affects children younger than 5. However, anyone who hasn’t been vaccinated is at risk of developing the disease.

Polio prevention

The most effective way to prevent polio is vaccination. Polio vaccine protects children by preparing their bodies to fight the polio virus. Almost all children (99 children out of 100) who get all the recommended doses of vaccine will be protected from polio.

There are two types of vaccine that can prevent polio: inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) and oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV). Only IPV has been used in the United States since 2000; OPV is still used throughout much of the world.

Polio Vaccines

There are two types of vaccine that protect against polio:

- Inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV)

- Oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV)

IPV (inactivated poliovirus vaccine) is given as an injection in the leg or arm, depending on the patient’s age. Polio vaccine may be given at the same time as other vaccines. Most people should get polio vaccine when they are children. Children get 4 doses of IPV at these ages: 2 months, 4 months, 6-18 months, and a booster dose at 4-6 years.

Oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV) has not been used in the United States since 2000 but is still used in many parts of the world. Since 2000, only inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) has been used in the United States to eliminate the risk of vaccine-derived poliovirus (VDPV) that can occur with oral poliovirus vaccine (OPV).

Who should get polio vaccine?

The CDC recommends that all children get four doses of polio vaccine as part of the routine childhood vaccination schedule.

Children should get one dose of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) at each of the following ages:

- 2 months old,

- 4 months old,

- 6 through 18 months old, and

- 4 through 6 years old.

Children who are unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated should see their healthcare professional to complete their polio vaccine series.

Most adults residing in the United States are presumed to be protected against polio because they received routine childhood immunization and have only a small risk of exposure to poliovirus in the United States.

Unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated adults who are at increased risk of exposure to poliovirus should receive and complete the polio vaccination series with inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV). Other adults who are unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated should talk with their doctor to understand their risk for polio and need for polio vaccination. Adults who are completely vaccinated but are at increased risk for exposure to poliovirus, including international travelers, laboratory workers, and healthcare workers, may receive a single lifetime booster dose of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV).

Infants and Children

Children in the United States should get inactivated polio vaccine (IPV) to protect against polio, or poliomyelitis. They should get four doses total, with one dose at each of the following ages 7:

- 2 months old

- 4 months old

- 6 through 18 months old

- 4 through 6 years old

Children who will be traveling to a country where the risk of getting polio is greater should complete the series before leaving for their trip. If a child cannot complete the routine series before leaving, an accelerated schedule is recommended as follows:

- 1 dose at age 6 weeks or older

- a second dose 4 or more weeks after the first dose

- a third dose 4 or more weeks after the second dose

- a fourth dose 6 or more months after the third dose

If the accelerated schedule cannot be completed before leaving, the remaining doses should be given in the affected country, or upon returning home, at the intervals recommended in the accelerated schedule. In addition, children completing the accelerated schedule should still receive a dose of IPV at 4 years old or older, as long as it has been at least 6 months after the last dose.

Adults

Most adults do not need polio vaccine because they were already vaccinated as children. But some adults are at higher risk and should consider polio vaccination in the following situations:

- You are traveling to a country where the risk of getting polio is greater. Ask your healthcare provider for specific information on whether you need to be vaccinated.

- You are working in a laboratory and handling specimens that might contain polioviruses.

- You are a healthcare worker treating patients who could have polio or have close contact with a person who could be infected with poliovirus.

- You are an unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated adult whose children will be receiving oral poliovirus vaccine (for example, international adoptees or refugees).

- You are an unvaccinated or incompletely vaccinated adult living or working in a community where poliovirus is circulating.

Adults in these groups who have never been vaccinated against polio should get 3 doses of IPV:

- The first dose at any time,

- The second dose 1 to 2 months later,

- The third dose 6 to 12 months after the second.

Adults in these groups who have had 1 or 2 doses of polio vaccine in the past should get the remaining 1 or 2 doses. It doesn’t matter how long it has been since the earlier dose(s).

Adults who are at increased risk of exposure to poliovirus and who have previously completed a routine series of polio vaccine (IPV or OPV) can receive one lifetime booster dose of IPV.

Who should NOT get polio vaccine?

Tell the person who is giving the vaccine:

- If the person getting the vaccine has any severe, life-threatening allergies.

- If you ever had a life-threatening allergic reaction after a dose of IPV, or have a severe allergy to any part of this vaccine, you may be advised not to get vaccinated. Ask your health care provider if you want information about vaccine components.

- If the person getting the vaccine is not feeling well.

- If you have a mild illness, such as a cold, you can probably get the vaccine today. If you are moderately or severely ill, you should probably wait until you recover. Your doctor can advise you.

IPV can cause an allergic reaction in some people. Because the vaccine has trace amounts of the antibiotics streptomycin, polymyxin B and neomycin, it may cause a reaction in people allergic to one of these antibiotics. A person who has a severe reaction to a first dose of IPV won’t get more doses.

Signs and symptoms of an allergic reaction usually occur within minutes to a few hours after the shot. Watch for:

- Skin reactions, including hives and itching and flushed or pale skin

- Low blood pressure (hypotension)

- Narrowing of the airways and a swollen tongue or throat, which can cause wheezing and trouble breathing

- A weak and fast pulse

- Nausea, vomiting or diarrhea

- Dizziness or fainting

If you or your child has an allergic reaction after any vaccination, get medical help right away.

How well does the polio vaccine work?

Inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV), which is the only polio vaccine that has been given in the United States since 2000, protects almost all children (99 out of 100) who get all the recommended doses. Two doses of IPV provide at least 90% protection, and three doses provide at least 99% protection. For best protection, children should get four doses of inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV).

What are the possible side effects of polio vaccine?

With any medicine, including vaccines, there is a chance of side effects. These are usually mild and go away on their own, but serious reactions are also possible.

Some people who get inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) get a sore spot where the shot was given. Inactivated poliovirus vaccine (IPV) has not been known to cause serious problems, and most people do not have any problems with it 7.

Other problems that could happen after this vaccine:

- People sometimes faint after a medical procedure, including vaccination. Sitting or lying down for about 15 minutes can help prevent fainting and injuries caused by a fall. Tell your provider if you feel dizzy, or have vision changes or ringing in the ears.

- Some people get shoulder pain that can be more severe and longer-lasting than the more routine soreness that can follow injections. This happens very rarely.

- Any medication can cause a severe allergic reaction. Such reactions from a vaccine are very rare, estimated at about 1 in a million doses, and would happen within a few minutes to a few hours after the vaccination.

As with any medicine, there is a very remote chance of a vaccine causing a serious injury or death.

Polio symptoms

Most people who get infected with poliovirus (about 72 out of 100) do not become ill and are not aware that they have the infection.

About 1 out of 4 people with poliovirus infection will have flu-like symptoms that may include:

- Sore throat

- Fever

- Tiredness

- Nausea and vomiting

- Headache

- Stomach pain

- Pain or stiffness in the back, neck, arms or legs

- Weak or tender muscles

These symptoms usually last 2 to 10 days then go away on their own.

In rare cases, poliovirus infection can be very serious. About 1 out of 200 people will have severe muscle weakness or paralysis in their arms, legs, head and neck, and the diaphragm (a chest muscle vital for breathing), known as acute flaccid paralysis, acute poliomyelitis or infantile paralysis. This paralysis or weakness can last a lifetime. Although most people recover completely, others develop irreversible paralysis, and some die.

A smaller proportion of people with poliovirus infection will develop other more serious symptoms that affect the brain and spinal cord:

- Paresthesia (feeling of pins and needles in the legs)

- Meningitis (infection of the covering of the spinal cord and/or brain) occurs in about 1 out of 25 people with poliovirus infection

- Paralysis (can’t move parts of the body) or weakness in the arms, legs, or both, occurs in about 1 out of 200 people with poliovirus infection

Paralysis is the most severe symptom associated with polio because it can lead to permanent disability and death. Between 2 and 10 out of 100 people who have paralysis from poliovirus infection die because the virus affects the muscles that help them breathe (the diaphragm).

Even children who seem to fully recover can develop new muscle pain, weakness, or paralysis as adults, 15 to 40 years later. This is called post-polio syndrome.

Abortive polio

About 5% of people with the poliovirus get a mild version of the disease called abortive poliomyelitis. This leads to flu-like symptoms that last 2 to 3 days. These include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Muscle aches

- Sore throat

- Stomachache

- Loss of appetite

- Nausea

- Vomiting

Nonparalytic polio

A more severe form of the disease, called nonparalytic polio, affects about 1% of those infected. While the illness lasts longer than a few days, it doesn’t cause paralysis. Besides having more-severe flu-like symptoms, nonparalytic polio symptoms may include:

Neck pain or stiffness

Aches or stiffness in the arms or legs

Severe headache

A second phase of symptoms may follow, or a person may seem to be getting better for a few days before a second phase starts. These symptoms include:

Stiffness of the spine and neck

Decreased reflexes

Muscle weakness

Paralytic polio

Paralytic polio is the most serious form of the disease is rare. Paralytic polio begins much like nonparalytic polio. But it progresses to more-severe signs and symptoms, including:

- Intense pain

- Extreme sensitivity to touch

- Tingling or pricking sensations

- Muscles spasms or twitching

- Muscles weakness progressing to a limp paralysis

Any combination of limbs may experience paralysis. But paralysis of one leg is most common, followed by paralysis of one arm.

Depending on the severity of paralytic polio, other signs or symptoms may include:

- Paralysis of muscles involved in breathing

- Difficulty swallowing

Post-polio syndrome

Post-polio syndrome is the term used to describe a collection of signs and symptoms that may be experienced by polio survivors decades after they recover from their initial poliovirus infection 8. Post-polio syndrome is characterized by a set of health problems, such as muscle weakness, muscle wasting (atrophy), fatigue (mental and physical), muscle and joint pain from joint deterioration, sleep disturbances, intolerance to cold, respiratory and swallowing difficulties and a recent increase in body mass that begins about 15 to 40 years after the initial poliovirus infection 9, 10, 11. Post-polio syndrome affects between 25 and 40 out of every 100 polio survivors.

Post-polio syndrome is a slowly progressive disease, usually insidious, with subacute onset, sometimes resulting in significant restrictions of activities associated with everyday life 12, 10, 13.

Post-polio syndrome common signs and symptoms include:

- Progressive muscle or joint weakness and pain

- Fatigue (mental and physical)

- Muscle wasting (atrophy)

- Breathing or swallowing problems

- Sleep-related breathing disorders, such as sleep apnea

- Decreased tolerance of cold temperatures

Some people with post-polio syndrome have only minor symptoms, while others develop more visible muscle weakness and atrophy (a decrease in muscle size). Post-polio syndrome is rarely life-threatening, but the symptoms can make it difficult for an affected person to function independently.

Unlike poliovirus, post-polio syndrome is not contagious. Only a polio survivor can develop post-polio syndrome.

The pathophysiology of post-polio syndrome remains unclear and different mechanisms have been proposed. The most accepted mechanism theorizes that degeneration or dysfunction of giant motor units, manifested by peripheral deterioration (axon and/or neuromuscular junction), probably as a result of metabolic requirements of giant motor units (muscle overuse), has a central role in the cause of the post-polio syndrome 14, 15. However, there are different hypotheses associated with the pathophysiology of post-polio syndrome, which include: muscle disuse, the normal loss of motor units with age, predisposition to motor neuron degeneration due to glial vascular and lymphatic damage, reactivation of the virus or persistent infection, immunological factors related to poliomyelitis, the effect of growth hormone and the combined effect of overuse, disuse, pain, body mass gain or other diseases 16, 17, 18, 19, 14.

Regarding the diagnostic criteria for post-polio syndrome, a clinical approach aimed at ruling out other neurological diseases, orthopedic conditions, psychiatric disorders or even consequences linked to the aging process is required, since these conditions could develop the same signs and symptoms as seen in post-polio syndrome 14, 20. Therefore, it is extremely important that patients should be managed by a multidisciplinary healthcare professional team that includes neurologists, rheumatologists, orthopedists, pulmonologists, physical education professionals, physical therapists, nutritionists, nurses and psychologists 14, 21, 22.

Despite the significant decline in the incidence of paralytic poliomyelitis, post-polio syndrome will remain a major health problem 3. In western countries, where the last large epidemics date back to the 1940s and 1950s, many survivors of paralytic poliomyelitis are now aged between 70 and 80 years 23. In Brazil, the last major outbreak was in 1984 23. Therefore, the future outlook is for continued or even increased need for rehabilitation programs and management of people with post-polio syndrome 14, 24. In addition, according to the World Health Organization (WHO), it is estimated that there are about 18 million people alive who were affected by paralytic poliomyelitis 3.

Poliomyelitis complications

Severe polio that affects your ability to breathe can cause death. Long-term complications for people who recover from polio may include:

- Permanent paralysis

- Muscle shortening that causes deformed bones or joints

- Chronic pain

- Post-polio syndrome

Polio diagnosis

Doctors often recognize polio by symptoms, such as neck and back stiffness, abnormal reflexes, and difficulty swallowing and breathing. To confirm the diagnosis, a sample of throat secretions, stool or a colorless fluid that surrounds your brain and spinal cord (cerebrospinal fluid) is checked for poliovirus.

Polio treatment

There’s currently no cure for polio. Treatment focuses on supporting bodily functions and reducing the risk of long-term problems while the body fights off the infection. This can include bed rest in hospital, painkillers, breathing support and regular stretches or exercises to prevent problems with the muscles and joints.

If you’re left with long-term problems as a result of a polio infection, you’ll probably need ongoing treatment and support.

This may include physiotherapy to help with any movement problems, devices such as splints and braces to support weak limbs or joints, occupational therapy to help you adapt to any difficulties, and possibly surgery to correct any deformities.

Depending on the severity of your polio, supportive treatments may include:

- Bed rest

- Pain relievers

- Hot moist packs to control muscle pain and spasms

- Portable ventilators to assist breathing

- Physical therapy exercises to prevent bone deformity and loss of muscle function

- Splints or other devices to encourage good position, or alignment, of the spine and limbs

Polio prognosis

The presentation of polio is highly variable, ranging from viral symptoms without paralysis to quadriplegia (paralysis that affects all four limbs, plus the torso) and even respiratory failure 25. Polio patients who present with only abortive poliomyelitis with flu-like symptoms that last 2 to 3 days are likely to see complete resolution of symptoms. For those that experience acute paralysis, the degree of paralysis often remains static. Approximately 30% to 40% of polio patients will develop post-polio syndrome decades after the primary infection. This progression is multifactorial and depends on factors like severity of acute paralysis, age of onset, and even socioeconomic status 26, 27, 13.

- Howard RS. Poliomyelitis and the postpolio syndrome. BMJ. 2005;330(7503):1314–1318. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7503.1314[↩]

- Schmidt S, Gocheva V, Zumbrunn T, et al. Treatment with L-citrulline in patients with post-polio syndrome: study protocol for a single-center, randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Trials. 2017;18(1):116–116. doi: 10.1186/s13063-017-1829-3[↩]

- Poliomyelitis. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/poliomyelitis[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Poliomyelitis: For Healthcare Providers. https://www.cdc.gov/polio/what-is-polio/hcp.html[↩]

- Vaccine-Derived Poliovirus. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/polio/hcp/vaccine-derived-poliovirus-faq.html[↩]

- Polio Vaccination. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/polio/index.html[↩]

- Polio Vaccination: What Everyone Should Know. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/vpd/polio/public/index.html[↩][↩]

- Dencker A, Sunnerhagen KS, Taft C, Lundgren-Nilsson Å. Multidimensional fatigue inventory and post-polio syndrome – a Rasch analysis. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2015;13(20) doi: 10.1186/s12955-015-0213-9[↩]

- Halstead LS, Rossi CD. New problems in old polio patients: results of a survey of 539 polio survivors. Orthopedics. 1985 Jul;8(7):845-50. doi: 10.3928/0147-7447-19850701-06[↩]

- Garip Y, Eser F, Bodur H, Baskan B, Sivas F, Yilmaz O. Health related quality of life in Turkish polio survivors: impact of post-polio on the health related quality of life in terms of functional status, severity of pain, fatigue, and social, and emotional functioning. Rev Bras Reumatol Engl Ed. 2017 Jan-Feb;57(1):1-7. English, Portuguese. doi: 10.1016/j.rbre.2014.12.006[↩][↩]

- de Lira CAB, de Almeida Alves TM, Peixinho-Pena LF, Sousa BS, de Santana MG, Benite-Ribeiro SA, Andrade MDS, Vancini RL. Knowledge among physical education professionals about poliomyelitis and post-poliomyelitis syndrome: a cross-sectional study in Brazil. Degener Neurol Neuromuscul Dis. 2013 Aug 8;3:41-46. doi: 10.2147/DNND.S45980[↩]

- Winberg C, Carlsson G, Brogårdh C, Lexell J. The Perception of Physical Activity in Ambulatory Persons with Late Effects of Polio: A Qualitative Study. J Aging Phys Act. 2017 Jan;25(1):65-72. doi: 10.1123/japa.2015-0282[↩]

- Lo, J.K. and Robinson, L.R. (2018), Postpolio syndrome and the late effects of poliomyelitis. Part 1. pathogenesis, biomechanical considerations, diagnosis, and investigations. Muscle Nerve, 58: 751-759. https://doi.org/10.1002/mus.26168[↩][↩]

- Lo JK, Robinson LR. Postpolio syndrome and the late effects of poliomyelitis. Part 1. pathogenesis, biomechanical considerations, diagnosis, and investigations. Muscle Nerve. 2018;58(6):751–9. doi: 10.1002/mus.26168[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Wiechers DO, Hubbell SL. Late changes in the motor unit after acute poliomyelitis. Muscle Nerve. 1981;4(6):524–528. doi: 10.1002/mus.880040610[↩]

- Voorn EL, Brehm MA, Beelen A, et al. Reliability of Contractile Properties of the Knee Extensor Muscles in Individuals with Post-Polio Syndrome. PLoS One. 2014;9(7):e101660. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101660[↩]

- Koopman FS, Beelen A, Gilhus NE, de Visser M, Nollet F. Treatment for postpolio syndrome. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;18(5):CD007818–CD007818. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007818.pub3[↩]

- Kosaka T, Kuroha Y, Tada M, et al. A fatal neuromuscular disease in an adult patient after poliomyelitis in early childhood: Consideration of the pathology of post-polio syndrome. Neuropathology. 2013;33(1):93–101. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1789.2012.01327.x[↩]

- Tersteeg IM, Koopman FS, Stolwijk-Swüste JM, Beelen A, Nollet F. A 5-Year Longitudinal Study of Fatigue in Patients With Late-Onset Sequelae of Poliomyelitis. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;92(6):899–904. doi: 10.1016/j.apmr.2011.01.005[↩]

- Dalakas MC. The post-polio syndrome as an evolved clinical entity. Definition and clinical description. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;753:68–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1995.tb27532.x[↩]

- Willén C, Thorén-Jönsson AL, Grimby G, Sunnerhagen KS. Disability in a 4-year follow-up study of people with post-polio syndrome. J Rehabil Med. 2007;39(2):175–180. doi: 10.2340/16501977-0034[↩]

- de Lira CAB, Vancini RL, Cabral FR, et al. Post-polio syndrome: renaissance of poliomyelitis? Einstein. 2009;7(2 Pt 1):225–228. https://apps.einstein.br/revista/arquivos/PDF/1236-Einsteinv7n2p225-8_ing.pdf[↩]

- Nathanson N, Kew OM. From emergence to eradication: the epidemiology of poliomyelitis deconstructed. Am J Epidemiol. 2010;172(11):1213–1229. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwq320[↩][↩]

- Lo JK, Robinson LR. Post-polio syndrome and the late effects of poliomyelitis: Part 2. treatment, management, and prognosis. Muscle Nerve. 2018;58(6):760–769. doi: 10.1002/mus.26167[↩]

- Wolbert JG, Higginbotham K. Poliomyelitis. [Updated 2022 Jun 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK558944[↩]

- Ragonese P, Fierro B, Salemi G, Randisi G, Buffa D, D’Amelio M, Aloisio A, Savettieri G. Prevalence and risk factors of post-polio syndrome in a cohort of polio survivors. J Neurol Sci. 2005 Sep 15;236(1-2):31-5. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2005.04.012[↩]

- Bang H, Suh JH, Lee SY, Kim K, Yang EJ, Jung SH, Jang SN, Han SJ, Kim WH, Oh MG, Kim JH, Lee SG, Lim JY. Post-polio syndrome and risk factors in korean polio survivors: a baseline survey by telephone interview. Ann Rehabil Med. 2014 Oct;38(5):637-47. doi: 10.5535/arm.2014.38.5.637[↩]