PPROM

Preterm premature rupture of membranes or PPROM is also known as preterm PROM, is a condition which occurs in pregnancy when the amniotic sac ruptures before 37 weeks of pregnancy and before labor 1. When birth occurs between 20 and 37 weeks of pregnancy, it is called preterm, or premature, birth. Preterm labor begins with contractions of the uterus before 37 weeks of pregnancy that cause the cervix to thin out and open up. If preterm labor cannot be stopped, it leads to preterm birth. PPROM increases the risk of prematurity and leads to a number of other perinatal and neonatal complications, including a 1 to 2 percent risk of fetal death 2. PPROM can result in significant neonatal morbidity and mortality, primarily from prematurity, sepsis, cord prolapse and pulmonary hypoplasia. In addition, there are risks associated with chorioamnionitis and placental abruption. Preterm births account for approximately 70% of newborn deaths and 36% of infant deaths. Ob-gyns, physicians whose primary responsibility is women’s health, play a leading role in diagnosing and treating premature labor and birth.

Preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM can be caused by a bacterial infection or by a defect in the structure of the amniotic sac, uterus, or cervix. In some cases, the leak can spontaneously heal, but in most cases of PPROM, labor begins within 48 hours of membrane rupture. When this occurs, it is necessary that the mother receive treatment to avoid possible infection in the newborn. The outcomes associated with PPROM include prematurity, oligohydramnios, abruption placentae, intrauterine infection, and chorioamnionitis 3.

The specific risk factors for PPROM were body mass index (BMI) <18.5 kg/m², history of PPROM, nulliparity (never having completed a pregnancy beyond 20 weeks), gestational diabetes and low level of education 4. The complications associated with PPROM were abruption placentae, cesarean, APGAR 5′ <4, birth weight <2500 g, stillbirth, neonatal jaundice, and hospitalization of mother and neonates. All these complications were also associated with spontaneous preterm labor with intact membranes 4.

Preterm prelabor rupture of membranes (PPROM) complicates up to 3% of pregnancies and is associated with 30-40% of all spontaneous preterm births 5.

According to national guidelines, conventional management of preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM) is hospitalization until induction. Outpatient management could be another option. Home management seems to be a safe option to hospitalization in selected patients with PPROM. However, a randomized study would be required to approve those results 6.

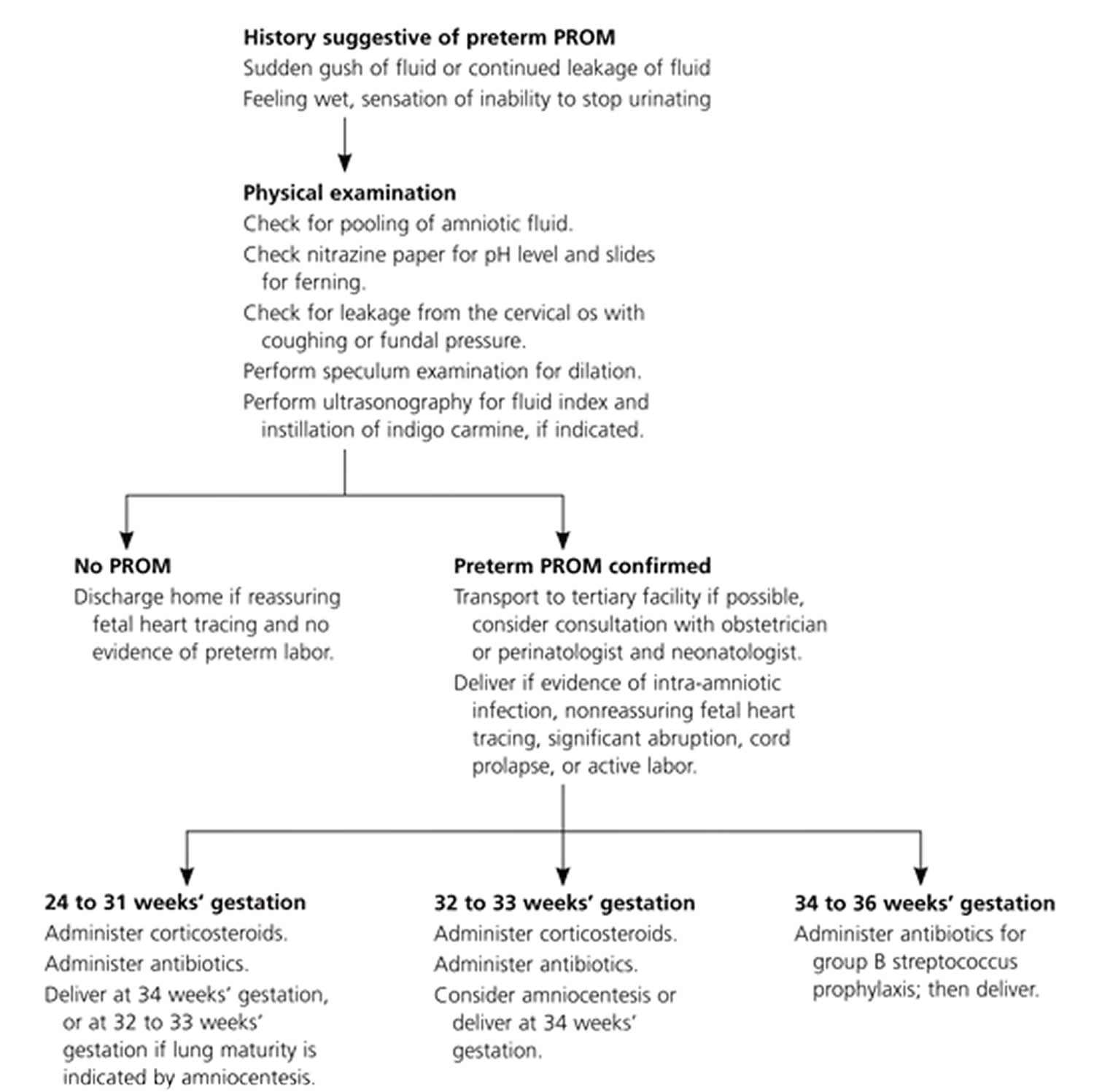

Figure 1. Management of patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes

[Source 7 ]PPROM causes

Although many factors can increase the risk of PPROM, its cause is not fully understood 8. PPROM arises from complex pathophysiological pathways that include inflammation and oxidative stress 9. Among the socio-behavioral and demographic risk factors of PPROM are poor socioeconomic status and low level of education, smoking, difficult working conditions, and African ethnicity 10. Other factors have been proposed, such as maternal age and increased or decreased body mass index (BMI) 11. Also, a history of PPROM, a history of prematurity, or multiple pregnancies are predominant considered risk factors 12. Other factors, such as nulliparity, the interval between pregnancies (<6 or >60 months), cervico-isthmic abnormalities, genital infections, and hydramnios, have also been reported 13.

Risk factors for PPROM

Numerous risk factors are associated with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Black patients are at increased risk of PPROM compared with white patients 14. Other patients at higher risk include those who have lower socioeconomic status, low level of education, BMI <18.5 kg/m², are smokers, have a history of sexually transmitted infections, have had a previous preterm delivery, history of PPROM, nulliparity, multiple pregnancies, the interval between pregnancies (<6 months or >60 months) 12, gestational diabetes, have vaginal bleeding, or have uterine distension (e.g., polyhydramnios, multifetal pregnancy) 15. Procedures that may result in preterm premature rupture of membrane include cerclage and amniocentesis. There appears to be no single cause of preterm premature rupture of membrane. Choriodecidual infection or inflammation may cause PPROM 16. A decrease in the collagen content of the membranes has been suggested to predispose patients to PPROM 17. It is likely that multiple factors predispose certain patients to preterm premature rupture of membranes.

PPROM complications

One of the most common complications of preterm premature rupture of membranes is early delivery. The latent period, which is the time from membrane rupture until delivery, generally is inversely proportional to the gestational age at which PPROM occurs. For example, one large study 18 of patients at term revealed that 95 percent of patients delivered within approximately one day of PROM, whereas an analysis of studies 19 evaluating patients with PPROM between 16 and 26 weeks’ gestation determined that 57 percent of patients delivered within one week, and 22 percent had a latent period of four weeks. When PROM occurs too early, surviving neonates may develop complications such as malpresentation, cord compression, oligohydramnios, necrotizing enterocolitis, neurologic impairment, intraventricular hemorrhage, and respiratory distress syndrome 7.

Table 1. Complications of preterm premature rupture of membranes

| Complications | Incidence (%) |

|---|---|

Delivery within one week | 50 to 75 |

Respiratory distress syndrome | 35 |

Cord compression | 32 to 76 |

Chorioamnionitis | 13 to 60 |

Abruptio placentae | 4 to 12 |

Antepartum fetal death | 1 to 2 |

PPROM diagnosis

The diagnosis of PPROM requires a thorough history, physical examination, and selected laboratory studies. Patients often report a sudden gush of fluid with continued leakage. Physicians should ask whether the patient is contracting, bleeding vaginally, has had intercourse recently, or has a fever. It is important to verify the patient’s estimated due date because this information will direct subsequent treatment.

The physician should perform a speculum examination to evaluate if any cervical dilation, pooling of amniotic fluid and effacement are present. When preterm premature rupture of membranes is suspected, it is important to avoid performing a digital cervical examination; such examinations have been shown to increase morbidity and mortality 20. Digital cervical examinations also cause an average nine-day decrease in the latent period 21. Shortening of the latent period may lead to increased infectious morbidity and complications from preterm labor. Some physicians are concerned that not performing a digital examination may lead to the misdiagnosis of advanced preterm labor with imminent delivery, which has important implications for patients who require transfer to a tertiary care center; however, a prospective comparison 22 found that the difference between digital and speculum examinations was not clinically significant. Physicians should be reassured that careful visual inspection via a speculum examination is the safest method for determining whether dilation has occurred after preterm premature rupture of membranes.

- If pooling of amniotic fluid is observed, do not perform any diagnostic test but offer care consistent with the woman having PPROM 23

- If pooling of amniotic fluid is not observed, perform an insulin-like growth factor binding protein‑1 test or placental alpha-microglobulin‑1 test of vaginal fluid 23.

- If the results of the insulin-like growth factor binding protein‑1 or placental alpha-microglobulin‑1 test are positive, do not use the test results alone to decide what care to offer the woman, but also take into account her clinical condition, her medical and pregnancy history and gestational age, and either 23:

- offer care consistent with the woman having PPROM or

- re-evaluate the woman’s diagnostic status at a later time point.

- If the results of the insulin-like growth factor binding protein‑1 or placental alpha-microglobulin‑1 test are negative and no amniotic fluid is observed 23:

- do not offer antenatal prophylactic antibiotics

- explain to the woman that it is unlikely that she has PPROM, but that she should return if she has any further symptoms suggestive of PPROM or preterm labor 23.

- If the results of the insulin-like growth factor binding protein‑1 or placental alpha-microglobulin‑1 test are positive, do not use the test results alone to decide what care to offer the woman, but also take into account her clinical condition, her medical and pregnancy history and gestational age, and either 23:

- Do not use nitrazine to diagnose PPROM 23.

- Do not perform diagnostic tests for PPROM if labour becomes established in a woman reporting symptoms suggestive of PPROM 23.

During the speculum examination, a DNA probe or cervical culture for chlamydia and gonorrhea should be performed, because women with these infections are seven times more likely to have PROM 24. After the speculum is removed, a vaginal and perianal (or anal) swab for group B streptococcus culture should be obtained.

Identifying infection in women with PPROM 23:

- Use a combination of clinical assessment and tests (C‑reactive protein, white blood cell count and measurement of fetal heart rate using cardiotocography) to diagnose intrauterine infection in women with PPROM.

- Do not use any one of the following in isolation to confirm or exclude intrauterine infection in women with PPROM:

- a single test of C‑reactive protein

- white blood cell count

- measurement of fetal heart rate using cardiotocography.

- If the results of the clinical assessment or any of the tests are not consistent with each other, continue to observe the woman and consider repeating the tests.

In unusual cases in which the patient’s history suggests preterm premature rupture of membranes, but physical examination findings fail to confirm the diagnosis, ultrasonography may be helpful. Occasionally, patients present with conflicting history and physical examination findings (e.g., a history highly suspicious for ruptured membranes with a normal fern test but positive nitrazine test). When ultrasonography is inconclusive or the clinical situation depends on a precise diagnosis (e.g., when contemplating transport to a tertiary care facility), amniocentesis may help determine whether the membranes are ruptured. The physician should instill 1 mL of indigo carmine dye mixed in 9 mL of sterile saline. If the membranes are ruptured, the blue dye should pass onto a vaginal tampon within 30 minutes of instillation. Methylin blue dye should not be used because it has been associated with hyperbilirubinemia and hemolytic anemia in infants 25. Even when ultrasonography is not necessary to confirm PROM, it may help determine the position of the fetus, placental location, estimated fetal weight, and presence of any anomalies.

PPROM treatment

34 to 36 weeks

When PPROM occurs at 34 to 36 weeks’ gestation, physicians should avoid the urge to prolong pregnancy. Studies have shown that labor induction clearly is beneficial at or after 34 weeks’ gestation. One study 26 showed that conservative management between 34 and 36 weeks’ gestational age resulted in an increased risk of chorioamnionitis and a lower average umbilical cord pH. Another study 27 of 430 women with preterm premature rupture of membranes revealed that there was no improvement in major or minor neonatal morbidity after 34 weeks’ gestation. Although corticosteroids are not indicated after 34 weeks’ gestation, physicians should prescribe appropriate antibiotics for group B streptococcus prophylaxis and should consider maternal transport to a facility skilled in caring for premature neonates, if possible. Preterm premature rupture of membranes is not a contraindication to vaginal delivery.

32 to 33 weeks

For patients with PPROM at 32 or 33 weeks’ gestation with documented pulmonary maturity, induction of labor and transportation to a facility that can perform amniocentesis and care for premature neonates should be considered 28. Prolonging pregnancy after documentation of pulmonary maturity unnecessarily increases the likelihood of maternal amnionitis, umbilical cord compression, prolonged hospitalization, and neonatal infection 29.

There are few data to guide the care of patients without documented pulmonary maturity. No studies are available comparing delivery with expectant management when patients receive evidence-based therapies such as corticosteroids and antibiotics. Physicians must balance the risk of respiratory distress syndrome and other complications of premature delivery with the risks of pregnancy prolongation, such as neonatal sepsis and cord accidents. Physicians should administer a course of corticosteroids and antibiotics to patients without documented fetal lung maturity and consider delivery 48 hours later or perform a careful assessment of fetal well-being, observe for intra-amniotic infection, and deliver at 34 weeks, as described above. Consultation with a neonatologist and physician experienced in the management of PPROM may be beneficial. Patients with amnionitis require broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy, and all patients should receive appropriate intrapartum group B streptococcus prophylaxis, if indicated.

24 to 31 weeks

Delivery before 32 weeks’ gestation may lead to severe neonatal morbidity and mortality. In the absence of intra-amniotic infection, the physician should attempt to prolong the pregnancy until 34 weeks’ gestation. Physicians should advise patients and family members that, despite these efforts, many patients deliver within one week of PPROM 19. Contraindications to conservative therapy include chorioamnionitis, abruptio placentae, and nonreassuring fetal testing. Physicians should administer a course of corticosteroids and antibiotics and perform an assessment of fetal well-being by fetal monitoring or ultrasonography. After transport to a facility able to care for patients with PPROM before 32 weeks’ gestation, patients should receive daily (or continuous, if indicated) fetal monitoring for contractions and fetal well-being. Umbilical cord compression is common (32 to 76 percent) 30 with PPROM before 32 weeks’ gestation; therefore, at least daily fetal monitoring is indicated. In addition, the physician should observe closely for fetal or maternal tachycardia, oral temperature exceeding 100.4°F (38°C), regular contractions, uterine tenderness, or leukocytosis, which are possible indicators of amnionitis. Corticosteroid administration may lead to an elevated leukocyte count if given within five to seven days of PROM.

Evidence suggests that prolonged latency may increase the risk of intra-amniotic infection. A retrospective analysis 31 of 134 women with preterm PROM at 24 to 32 weeks’ gestation who received steroids and antibiotics found a nonsignificant trend toward intrauterine inflammation in patients with a latency period longer than one week. Delivery is necessary for patients with evidence of amnionitis. If the diagnosis of an intrauterine infection is suspected but not established, amniocentesis can be performed to check for a decreased glucose level or a positive Gram stain and differential count can be performed 29. For patients who reach 32 to 33 weeks’ gestation, amniocentesis for fetal lung maturity and delivery after documentation of pulmonary maturity, evidence of intra-amniotic infection, or at 34 weeks’ gestation should be considered.

Before 24 weeks

The majority of patients will deliver within one week when PPROM occurs before 24 weeks’ gestation, with an average latency period of six days 32. Many infants who are delivered after previable rupture of the fetal membranes suffer from numerous long-term problems including chronic lung disease, developmental and neurologic abnormalities, hydrocephalus, and cerebral palsy. Previable rupture of membranes also can lead to Potter’s syndrome, which results in pressure deformities of the limbs and face and pulmonary hypoplasia. The incidence of this syndrome is related to the gestational age at which rupture occurs and to the level of oligohydramnios. Fifty percent of infants with rupture at 19 weeks’ gestation or earlier are affected by Potter’s syndrome, whereas 25 percent born at 22 weeks’ and 10 percent after 26 weeks’ gestation are affected 33. Patients should be counseled about the outcomes and benefits and risks of expectant management, which may not continue long enough to deliver a baby that will survive normally.

Physicians caring for patients with PPROM before viability may wish to obtain consultation with a perinatologist or neonatologist. Such patients, if they are stable, may benefit from transport to a tertiary facility. Home management of patients with PPROM is controversial. A study 34 of patients with PPROM randomized to home versus hospital management revealed that only 18 percent of patients met criteria for safe home management. Bed rest at home before viability (i.e., approximately 24 weeks’ gestation) may be acceptable for patients without evidence of infection or active labor, although they must receive precise education about symptoms of infection and preterm labor, and physicians should consider consultation with experts familiar with home management of PPROM. Consider readmission to the hospital for these patients after 24 weeks’ gestation to allow for close fetal and maternal monitoring.

Medications

Corticosteroids

Corticosteroids decrease perinatal morbidity and mortality after preterm premature rupture of membranes 35. A recent meta-analysis 35. found that corticosteroid administration after preterm premature rupture of membranes, versus no administration, reduced the risk of respiratory distress syndrome (20 versus 35.4 percent), intraventricular hemorrhage (7.5 versus 15.9 percent), and necrotizing enterocolitis (0.8 versus 4.6 percent) without an increase in the risk of maternal or neonatal infection. Because corticosteroids are effective at decreasing perinatal morbidity and mortality, all physicians caring for pregnant women should understand the dosing and indications for corticosteroid administration during pregnancy. The most widely used and recommended regimens include intramuscular betamethasone (Celestone) 12 mg every 24 hours for two days, or intramuscular dexamethasone (Decadron) 6 mg every 12 hours for two days 36. The National Institutes of Health recommends administration of corticosteroids before 30 to 32 weeks’ gestation, assuming fetal viability and no evidence of intra-amniotic infection. Use of corticosteroids between 32 and 34 weeks is controversial. Administration of corticosteroids after 34 weeks’ gestation is not recommended unless there is evidence of fetal lung immaturity by amniocentesis. Multiple courses are not recommended because studies have shown that two or more courses can result in decreased infant birth weight, head circumference, and body length 37.

Maternal corticosteroids 23:

- For women between 23+0 and 23+6 weeks of pregnancy who are in suspected or established preterm labour, are having a planned preterm birth or have PPROM, discuss with the woman (and her family members or carers as appropriate) the use of maternal corticosteroids in the context of her individual circumstances.

- Offer maternal corticosteroids to women between 24+0 and 33+6 weeks of pregnancy who are in suspected, diagnosed or established preterm labour, are having a planned preterm birth or have PPROM.

- Consider maternal corticosteroids for women between 34+0 and 35+6 weeks of pregnancy who are in suspected, diagnosed or established preterm labour, are having a planned preterm birth or have PPROM.

- When offering or considering maternal corticosteroids, discuss with the woman (and her family members or carers as appropriate):

- how corticosteroids may help

- the potential risks associated with them.

- Do not routinely offer repeat courses of maternal corticosteroids, but take into account:

- the interval since the end of last course

- gestational age

- the likelihood of birth within 48 hours.

- For guidance on the use of corticosteroids in women with diabetes, see the NICE guideline on diabetes in pregnancy (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng3).

Antibiotics

Giving antibiotics to patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes can reduce neonatal infections and prolong the latent period. A meta-analysis2 showed that patients receiving antibiotics after preterm premature rupture of membranes, compared with those not receiving antibiotics experienced reduced postpartum endometritis, chorioamnionitis, neonatal sepsis, neonatal pneumonia, and intraventricular hemorrhage. Another meta-analysis 38 found a decrease in neonatal intraventricular hemorrhage and sepsis. A number of antibiotic regimens are advocated for use after preterm premature rupture of membranes. The regimen studied by the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development trial 39 uses an intravenous combination of 2 grams of ampicillin and 250 mg of erythromycin every six hours for 48 hours, followed by 250 mg of amoxicillin and 333 mg of erythromycin every eight hours for five days. Women given this combination were more likely to stay pregnant for three weeks despite discontinuation of the antibiotics after seven days. It is advisable to administer appropriate antibiotics for intrapartum group B streptococcus prophylaxis to women who are carriers, even if these patients have previously received a course of antibiotics after preterm premature rupture of membranes.

Antenatal prophylactic antibiotics for women with PPROM 23:

- Offer women with PPROM oral erythromycin 250 mg 4 times a day for a maximum of 10 days or until the woman is in established labour (whichever is sooner).

- For women with PPROM who cannot tolerate erythromycin or in whom erythromycin is contraindicated, consider an oral penicillin for a maximum of 10 days or until the woman is in established labour (whichever is sooner).

- Do not offer women with PPROM co‑amoxiclav as prophylaxis for intrauterine infection.

- For guidance on the use of intrapartum antibiotics, see the NICE guideline on neonatal infection (early onset) (https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg149).

Tocolytic therapy

Limited data are available to help determine whether tocolytic therapy is indicated after preterm premature rupture of membranes. As described above, corticosteroids and antibiotics are beneficial when administered to patients with preterm premature rupture of membranes, but no studies of these therapies combined with tocolysis are available. Tocolytic therapy may prolong the latent period for a short time but do not appear to improve neonatal outcomes 40 In the absence of data, it is not unreasonable to administer a short course of tocolysis after preterm premature rupture of membranes to allow initiation of antibiotics, corticosteroid administration, and maternal transport 41, although this is controversial. Long-term tocolytic therapy in patients with PROM is not recommended; consideration of this should await further research.

Take the following factors into account when making a decision about whether to start tocolysis 23:

- whether the woman is in suspected or diagnosed preterm labour

- other clinical features (for example, bleeding or infection) that may suggest that stopping labour is contraindicated

- gestational age at presentation

- likely benefit of maternal corticosteroids

- availability of neonatal care (need for transfer to another unit)

- the preference of the woman.

Consider nifedipine for tocolysis for women between 24+0 and 25+6 weeks of pregnancy who have intact membranes and are in suspected preterm labor.

Offer nifedipine for tocolysis to women between 26+0 and 33+6 weeks of pregnancy who have intact membranes and are in suspected or diagnosed preterm labor.

If nifedipine is contraindicated, offer oxytocin receptor antagonists for tocolysis.

Do not offer betamimetics for tocolysis.

Magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection

For women between 23+0 and 23+6 weeks of pregnancy who are in established preterm labour or having a planned preterm birth within 24 hours, discuss with the woman (and her family members or carers as appropriate) the use of intravenous magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection of the baby, in the context of her individual circumstances 23.

Offer intravenous magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection of the baby to women between 24+0 and 29+6 weeks of pregnancy who are 23:

- in established preterm labour or

- having a planned preterm birth within 24 hours.

Consider intravenous magnesium sulfate for neuroprotection of the baby for women between 30+0 and 33+6 weeks of pregnancy who are 23:

- in established preterm labor or

- having a planned preterm birth within 24 hours.

Give a 4 g intravenous bolus of magnesium sulfate over 15 minutes, followed by an intravenous infusion of 1 g per hour until the birth or for 24 hours (whichever is sooner) 23.

For women on magnesium sulfate, monitor for clinical signs of magnesium toxicity at least every 4 hours by recording pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate and deep tendon (for example, patellar) reflexes.

If a woman has or develops oliguria or other signs of renal failure:

- monitor more frequently for magnesium toxicity

- think about reducing the dose of magnesium sulfate.

Prophylactic vaginal progesterone and prophylactic cervical cerclage

Offer a choice of prophylactic vaginal progesterone or prophylactic cervical cerclage to women who have both 23:

- a history of spontaneous preterm birth (up to 34+0 weeks of pregnancy) or mid-trimester loss (from 16+0 weeks of pregnancy onwards) and

- results from a transvaginal ultrasound scan carried out between 16+0 and 24+0 weeks of pregnancy that show a cervical length of 25 mm or less.

Discuss the risks and benefits of both options with the woman, and make a shared decision on which treatment is most suitable.

Consider prophylactic vaginal progesterone for women who have either 23:

- a history of spontaneous preterm birth (up to 34+0 weeks of pregnancy) or mid-trimester loss (from 16+0 weeks of pregnancy onwards) or

- results from a transvaginal ultrasound scan carried out between 16+0 and 24+0 weeks of pregnancy that show a cervical length of 25 mm or less.

When using vaginal progesterone, start treatment between 16+0 and 24+0 weeks of pregnancy and continue until at least 34 weeks.

Consider prophylactic cervical cerclage for women when results of a transvaginal ultrasound scan carried out between 16+0 and 24+0 weeks of pregnancy show a cervical length of 25 mm or less, and who have had either 23:

- preterm prelabour rupture of membranes (PPROM) in a previous pregnancy or

- a history of cervical trauma.

If prophylactic cervical cerclage is used, ensure that a plan is in place for removal of the suture.

Rescue cervical cerclage

Do not offer ‘rescue’ cervical cerclage to women with 23:

- signs of infection or

- active vaginal bleeding or

- uterine contractions.

Consider ‘rescue’ cervical cerclage for women between 16+0 and 27+6 weeks of pregnancy with a dilated cervix and exposed, unruptured fetal membranes 23:

- take into account gestational age (being aware that the benefits are likely to be greater for earlier gestations) and the extent of cervical dilatation

- discuss with a consultant obstetrician and consultant paediatrician.

Explain to women for whom ‘rescue’ cervical cerclage is being considered (and their family members or carers as appropriate) 23:

- about the risks of the procedure

- that it aims to delay the birth, and so increase the likelihood of the baby surviving and of reducing serious neonatal morbidity.

If ‘rescue’ cervical cerclage is used, ensure that a plan is in place for removal of the suture.

- Shad H. Deering, Neeta Patel, Catherine Y. Spong, John C. Pezzullo & Alessandro Ghidini (2007) Fetal growth after preterm premature rupture of membranes: Is it related to amniotic fluid volume?, The Journal of Maternal-Fetal & Neonatal Medicine, 20:5, 397-400, DOI: 10.1080/14767050701280249[↩]

- Mercer BM, Arheart KL. Antimicrobial therapy in expectant management of preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Lancet. 1995;346:1271–9.[↩]

- Kacerovsky, M.; Musilova, I.; Andrys, C.; Drahosova, M.; Hornychova, H.; Rezac, A.; Kostal, M.; Jacobsson, B. Oligohydramnios in women with preterm prelabor rupture of membranes and adverse pregnancy and neonatal outcomes. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e105882[↩]

- Bouvier, D.; Forest, J.-C.; Blanchon, L.; Bujold, E.; Pereira, B.; Bernard, N.; Gallot, D.; Sapin, V.; Giguère, Y. Risk Factors and Outcomes of Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes in a Cohort of 6968 Pregnant Women Prospectively Recruited. J. Clin. Med. 2019, 8, 1987. https://www.mdpi.com/2077-0383/8/11/1987/htm[↩][↩]

- Mercer, B.M.; Goldenberg, R.L.; Meis, P.J.; Moawad, A.H.; Shellhaas, C.; Das, A.; Menard, M.K.; Caritis, S.N.; Thurnau, G.R.; Dombrowski, M.P.; et al. The Preterm Prediction Study: Prediction of preterm premature rupture of membranes through clinical findings and ancillary testing. The National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2000, 183, 738–745.[↩]

- Is homecare management associated with longer latency in preterm premature rupture of membranes? Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2019 Nov 23. doi: 10.1007/s00404-019-05363-x. [Epub ahead of print] https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00404-019-05363-x[↩]

- Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes: Diagnosis and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2006 Feb 15;73(4):659-664. https://www.aafp.org/afp/2006/0215/p659.html[↩][↩][↩]

- Lorthe, E. [Epidemiology, risk factors and child prognosis: CNGOF Preterm Premature Rupture of Membranes Guidelines]. Gynecol. Obstet. Fertil. Senol. 2018, 46, 1004–1021.[↩]

- Menon, R.; Richardson, L.S. Preterm prelabor rupture of the membranes: A disease of the fetal membranes. Semin. Perinatol. 2017, 41, 409–419.[↩]

- Shen, T.T.; DeFranco, E.A.; Stamilio, D.M.; Chang, J.J.; Muglia, L.J. A population-based study of race-specific risk for preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008, 199, 373.e1–373.e7[↩]

- Berkowitz, G.S.; Blackmore-Prince, C.; Lapinski, R.H.; Savitz, D.A. Risk factors for preterm birth subtypes. Epidemiol. Camb. Mass. 1998, 9, 279–285.[↩]

- Jelliffe-Pawlowski, L.L.; Baer, R.J.; Blumenfeld, Y.J.; Ryckman, K.K.; O’Brodovich, H.M.; Gould, J.B.; Druzin, M.L.; El-Sayed, Y.Y.; Lyell, D.J.; Stevenson, D.K.; et al. Maternal characteristics and mid-pregnancy serum biomarkers as risk factors for subtypes of preterm birth. BJOG 2015, 122, 1484–1493.[↩][↩]

- Shree, R.; Caughey, A.B.; Chandrasekaran, S. Short interpregnancy interval increases the risk of preterm premature rupture of membranes and early delivery. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2018, 31, 3014–3020.[↩]

- Savitz DA, Blackmore CA, Thorp JM. Epidemiologic characteristics of preterm delivery: etiologic heterogeneity. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;164:467–71.[↩]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Premature rupture of membranes. Clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 1. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 1998;63:75–84.[↩]

- Bendon RW, Faye-Petersen O, Pavlova Z, Qureshi F, Mercer B, Miodovnik M, et al. Fetal membrane histology in preterm premature rupture of membranes: comparison to controls, and between antibiotic and placebo treatment. Pediatr Dev Pathol. 1999;2:552–8.[↩]

- Stuart EL, Evans GS, Lin YS, Powers HJ. Reduced collagen and ascorbic acid concentrations and increased proteolytic susceptibility with prelabor fetal membrane rupture in women. Biol Reprod. 2005;72:230–5.[↩]

- Hannah ME, Ohlsson A, Farine D, Hewson SA, Hodnett ED, Myhr TL, et al. Induction of labor compared with expectant management for prelabor rupture of the membranes at term. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1005–10.[↩]

- Schucker JL, Mercer BM. Midtrimester premature rupture of the membranes. Semin Perinatol. 1996;20:389–400.[↩][↩]

- Alexander JM, Mercer BM, Miodovnik M, Thurnau GR, Goldenburg RL, Das AF, et al. The impact of digital cervical examination on expectantly managed preterm rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:1003–7.[↩]

- Lewis DF, Major CA, Towers CV, Asrat T, Harding JA, Garite TJ. Effects of digital vaginal examinations on latency period in preterm premature rupture of membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:630–4.[↩]

- Munson LA, Graham A, Koos BJ, Valenzuela GJ. Is there a need for digital examination in patients with spontaneous rupture of the membranes?. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153:562–3.[↩]

- Preterm labour and birth. NICE guideline [NG25] August 2019. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng25/chapter/Recommendations[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Ekwo EE, Gosselink CA, Woolson R, Moawad A. Risks for premature rupture of amniotic membranes. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:495–503.[↩]

- Naylor CS, Gregory K, Hobel C. Premature rupture of the membranes: an evidence-based approach to clinical care. Am J Perinatol. 2001;18:397–413.[↩]

- Naef RW III, Allbert JR, Ross EL, Weber BM, Martin RW, Morrison JC. Premature rupture of membranes at 34 to 37 weeks’ gestation: aggressive versus conservative management. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;178(1 pt 1):126–30.[↩]

- Lieman JM, Brumfield CG, Carlo W, Ramsey PS. Preterm premature rupture of membranes: is there an optimal gestational age for delivery?. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:12–7.[↩]

- Ehernberg HM, Mercer BM. Antibiotics and the management of preterm premature rupture of the fetal membranes. Clin Perinatol. 2001;28:807–18.[↩]

- Mercer BM. Preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;101:178–93.[↩][↩]

- Smith CV, Greenspoon J, Phelan JP, Platt LD. Clinical utility of the nonstress test in the conservative management of women with preterm spontaneous premature rupture of the membranes. J Reprod Med. 1987;32:1–4.[↩]

- Gopalani S, Krohn M, Meyn L, Hitti J, Crombleholma WR. Contemporary management of preterm premature rupture of membranes: determinants of latency and neonatal outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;60:16–7.[↩]

- Schutte MF, Treffers PE, Kloosterman GJ, Soepatmi S. Management of premature rupture of membranes: the risk of vaginal examination to the infant. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1983;146:395–400.[↩]

- Rotschild A, Ling EW, Puterman ML, Farquharson D. Neonatal outcome after prolonged preterm rupture of the membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:46–52.[↩]

- Carlan SJ, O’Brien WF, Parsons MT, Lense JJ. Preterm premature rupture of membranes: a randomized study of home versus hospital management. Obstet Gynecol. 1993;81:61–4.[↩]

- Harding JE, Pang J, Knight DB, Liggins GC. Do antenatal corticosteroids help in the setting of preterm rupture of membranes?. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:131–9.[↩][↩]

- Effect of corticosteroids for fetal maturation on perinatal outcomes.. NIH Consens Statement. 1994;12:1–24.[↩]

- Vidaeff AC, Doyle NM, Gilstrap LC III. Antenatal corticosteroids for fetal maturation in women at risk for preterm delivery. Clin Perinatol. 2003;30:825–40,vii.[↩]

- Egarter C, Leitich H, Karas H, Wieser F, Husslein P, Kaider A, et al. Antibiotic treatment in preterm premature rupture of membranes and neonatal morbidity: a metaanalysis. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:589–97.[↩]

- Mercer BM, Miodovnik M, Thurnau GR, Goldenburg RL, Das AF, Ramsey RD, et al. Antibiotic therapy for reduction of infant morbidity after preterm premature rupture of the membranes. A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 1997;278:989–95.[↩]

- Weiner CP, Renk K, Klugman M. The therapeutic efficacy and cost-effectiveness of aggressive tocolysis for premature labor associated with premature rupture of the membranes [published correction appears in Am J Obstet Gynecol 1991;165:785]. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:216–22.[↩]

- Fontenot T, Lewis DF. Tocolytic therapy with preterm premature rupture of membranes. Clin Perinatol. 2001;28:787–96,vi.[↩]