What is propolis

Propolis is a resinous substance or “bee glue” synthesized by honeybees (Apis species) using products present on floral buds, gems, and vegetable cuts 1. The word “propolis” is derived from Greek to mean defense for “pro” and city or community for “polis”, or the beehive, in other words 2. Bees collect resins from buds, exudates and other parts of plants, mix them with their own salivary enzymes and beeswax which creates propolis 3. Propolis is composed of a mixture of different plants parts and molecules secreted by bees 1. Propolis is composed mainly of resin (50%), wax (30%), essential oils (10%), pollen (5%), and other organic compounds (5%) 4. Propolis functions in sealing holes and cracks and for the reconstruction of the beehive. Propolis is also used for smoothing the inner surface of the beehive, retaining the hive’s internal temperature (35°C), preventing weathering and invasion by predators 5. Furthermore, propolis hardens the cell wall and contributes to an aseptic internal environment. Propolis generally becomes soft and sticky upon heating 6. Propolis also possesses a pleasant smell.

The important organic compounds present in propolis are phenolic compounds, esters, flavonoids, terpenes, beta-steroids, aromatic aldehydes, and alcohols 7. Twelve different flavonoids, namely, pinocembrin, acacetin, chrysin, rutin, luteolin, kaempferol, apigenin, myricetin, catechin, naringenin, galangin, and quercetin; two phenolic acids, caffeic acid and cinnamic acid; and one stilbene derivative called resveratrol have been detected in propolis extracts by capillary zone electrophoresis 8. Propolis also contains important vitamins, such as vitamins B1 (Thiamine), B2 (Riboflavin), B6 (Pyridoxine), C (ascorbic acid), and vitamin E and useful minerals such as magnesium (Mg), calcium (Ca), potassium (K), sodium (Na), copper (Cu), zinc (Zn), manganese (Mn), and iron (Fe). A few enzymes, such as succinic dehydrogenase, glucose-6-phosphatase, adenosine triphosphatase, and acid phosphatase, are also present in propolis 9.

Besides being used as a material for repair, isolation, fixation, and microbiological protection of bee hives, its use as a therapeutic for several diseases has been reported 10. Propolis and its extracts have numerous applications in treating various diseases due to its antiseptic, anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, antibacterial, antimycotic, antifungal, antiulcer, anticancer, and immunomodulatory properties. Green propolis contains a significant amount of Artepillin C, a cinnamic acid derivative 11. Artepillin C acts as an anti-inflammatory and anti-bacterial component when combined with other compounds present in green propolis 12. When propolis was first isolated and identified, it was found to have a significant anti-bacterial potential 13. The anti-bacterial action of propolis is mainly demonstrated on Gram-positive bacteria 14 and has been tested as a major component of many pharmacological compounds used for various purposes, such as wound healing, anti-inflammatory action, and anti-bacterial activities in lab rats 15.

Another type of propolis comes from stingless bees (e.g., Melipona mondury, Melipona scutellaris) and it is called geopropolis. Geopropolis is very similar to propolis produced by bees belonging to Apis spp. in both composition and biological activity 16. Torres et al. 17 in their study compared two ethanolic extracts of propolis collected from a stingless species of bees, Melipona quadrifasciata and Tetragonisca angustula. The study showed the more significant activity of geopropolis extracts against Gram-positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus MSSA and MRSA, Enterococcus faecalis) than Gram-negative (Klebsiella pneumoniae, Escherichia coli). From the two geopropolis which were analyzed, the Melipona species was more effective 17.

Propolis chemical compounds

The chemical composition of propolis is closely related to the resins and balsams of plant sources used to produce it. Along with the progress of research, more than 300 chemical components of propolis have been identified 18. The main groups of chemical compounds found to be present in propolis except resins are waxes, polyphenols (phenolic acids, flavonoids) and terpenoids. The activity of propolis depends on chemical composition and is different in individual countries.

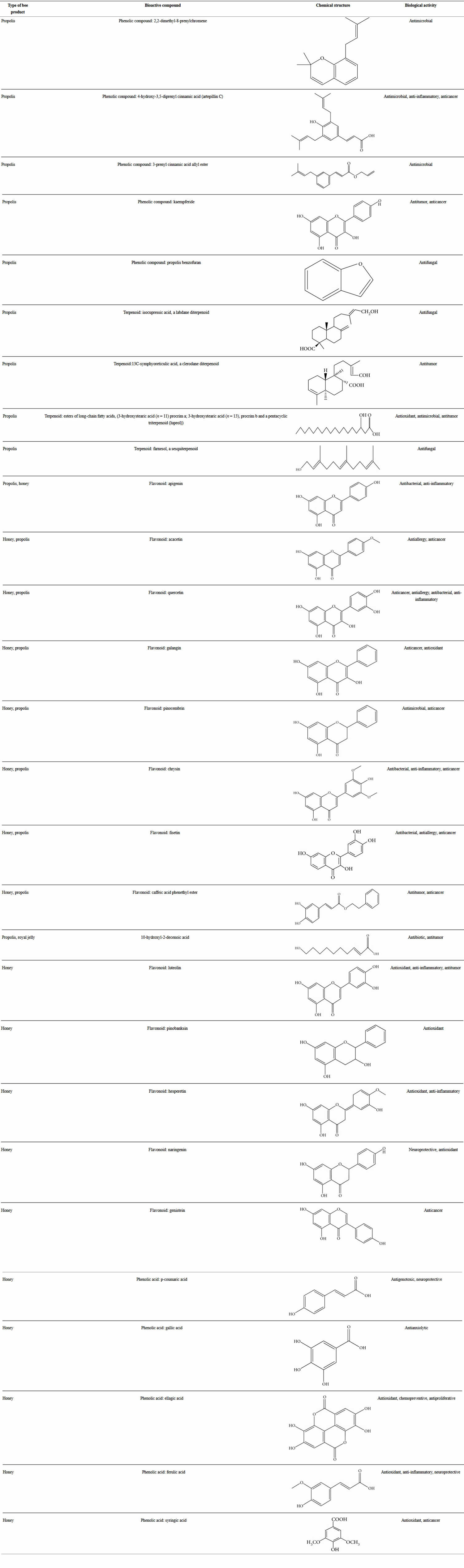

Polyphenols and terpenoids are also considered to be the most active 19. The flavonoid group includes chrysin, pinocembrin, apigenin, galangin, kaempferol, quercetin, tectochrysin, pinostrobin and others (see Figure 1). Another critical group of compounds of propolis are aromatic acids, among which the most often occur in ferulic, cinnamic, caffeic, benzoic, salicylic and p-cumaric acids 20. In Polish propolis, the content of flavonoid compounds ranged from 6.2 to 18.8%. Among the flavonoids, the highest amounts were pinocembrin (mean 4.7%), pinobenchin (mean 3.1%), galangin (mean 2.2%) and chrysin (mean 2.1%) 20. In addition, propolis also includes other phenolic compounds (e.g., artepillin C), and terpenes (terpineol, camphor, geraniol, nerol, farnesol) which are responsible for its characteristic fragrance 18. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) is considered an anti-obesity agent with beneficial effects on inflammation and diabetes 21. CAPE reduced insulin resistance in diabetic mice and in hepatic cell culture 22. Chrysin, another component of propolis, also has antidiabetic properties 23. In propolis, micro and macroelements (manganese, iron, silicon, magnesium, zinc, selenium, calcium, potassium, sodium, copper) and vitamins B1, B2, B6, C and E can be found 24. This diversity of the chemical composition gives propolis an additional advantage as an antibacterial agent. The combination of many active ingredients and their presence in various proportions prevents the bacterial resistance from occurring 25.

Figure 1. Important bioactive compounds in propolis, honey and royal jelly.

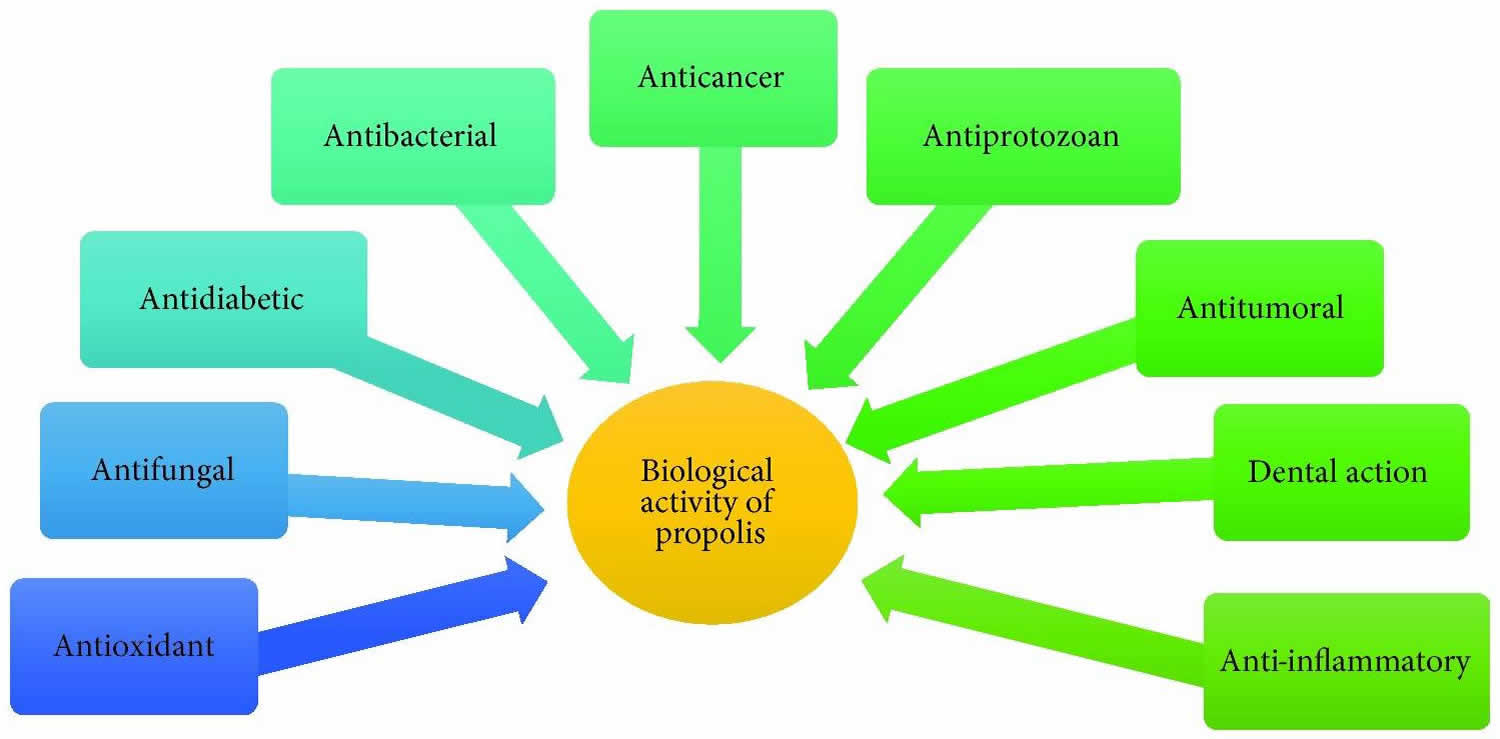

Figure 2. Biological activities of propolis

[Source 5 ]What are health benefits of propolis?

Propolis has been reported to have various health benefits related to gastrointestinal disorders, allergies, and gynecological, oral, and dermatological problems.

Propolis is possibly effective for:

- Diabetes. Research shows that taking propolis may improve blood sugar control by a small amount in people with diabetes. But it doesn’t seem to affect insulin levels or improve insulin resistance.

- Cold sores (herpes labialis). Most research shows that applying an ointment or cream containing 0.5% to 3% propolis five times daily helps cold sores to heal faster and reduces pain.

- Swelling (inflammation) and sores inside the mouth (oral mucositis). Most research shows that rinsing the mouth with a propolis mouth rinse helps heal sores caused by cancer drugs or dentures.

Insufficient evidence to rate effectiveness for:

- Prone to allergies and allergic reactions (atopic disease). Early research shows that taking propolis while nursing a newborn infant doesn’t seem to reduce the child’s risk of developing allergies at one year of age.

- Burns. Early research shows that applying propolis to the skin every 3 days might help treat minor burns and prevent infections.

- Canker sores. Early research shows that taking propolis by mouth daily for 6-13 months reduces canker sore outbreaks.

- A painful disease transmitted by mosquitos (dengue fever). Research shows that taking propolis helps people with dengue fever leave the hospital faster. It is not known if propolis helps with symptoms of dengue fever.

- Foot sores in people with diabetes. Early research shows that applying a propolis ointment to sores on the feet of people with diabetes might help the sores to heal faster.

- Genital herpes. Early research shows that applying a 3% propolis ointment four times daily for 10 days might improve healing of lesions in people with genital herpes. Some research suggests that it might heal lesions faster and more completely than the conventional treatment 5% acyclovir ointment.

- A mild form of gum disease (gingivitis). Early research suggests that using propolis in a gel or a rinse might help prevent or reduce signs of gum disease.

- A digestive tract infection that can lead to ulcers (Helicobacter pylori or H. pylori). Early research shows that taking 60 drops of a preparation containing Brazilian green propolis daily for 7 days does not reduce H. pylori infection.

- Infection of the intestines by parasites. Early research suggests that taking a 30% propolis extract for 5 days can cure giardiasis in more people than the drug tinidazole.

- Thrush. Early research suggests that using Brazilian green propolis extract four times daily for 7 days can prevent oral thrush in people with dentures.

- A serious gum infection (periodontitis). Early research shows that deeply rinsing the gums with a propolis extract solution decreases bleeding of gums in people with periodontitis. Taking propolis by mouth helps to prevent loose teeth in people with this condition. But taking propolis by mouth doesn’t seem to help with plaque or bleeding.

- Athlete’s foot (Tinea pedis). Early research shows that applying Brazilian green propolis to the skin decreases itching, peeling, and redness in students with athlete’s foot.

- Upper airway infection. There is some early evidence that propolis might help prevent or reduce the duration of common colds and other upper airway infections.

- Swelling (inflammation) of the vagina (vaginitis). Early research suggests that applying a 5% propolis solution vaginally for 7 days can reduce symptoms and improve quality of life in people with vaginal swelling.

- Warts. Early research shows that taking propolis by mouth daily for up to 3 months cures warts in some people with plane and common warts. However, propolis does not seem to treat plantar warts.

- Wound healing. Early research shows that using a propolis mouth rinse five times daily for 1 week might improve healing and reduce pain and swelling after mouth surgery. However, if people are already using a special dressing after dental surgery, using a propolis solution in the mouth does not seem to offer additional benefit.

- Improving immune response.

- Infections.

- Infections of the kidney, bladder, or urethra (urinary tract infections or UTIs).

- Inflammation.

- Nose and throat cancer.

- Stomach and intestinal disorders.

- Tuberculosis.

- Ulcers.

- Other conditions.

More evidence is needed to rate propolis for these uses.

Table 1. Propolis health benefits

| Health benefits | Propolis activity | Type of studies | Authors |

| Gastrointestinal disorder | Antiparasitic | Humans | Freitas et al. 2006 26 |

| Antiulceration | Animals | Paulino et al. 2015 27 | |

| Gynecological care | Antifungal | Human | Imhof et al. 2005 28 |

| Antifungal and antibiofilm | Human | Capoci et al. 2015 29 | |

| Oral health | Antibacterial | Laboratory | Pereira et al. 2011 30 |

| Daily mouthwash | Human | Jain et al. 2014 31 | |

| Toothpaste disinfection | Laboratory | Bertolini et al. 2012 32 | |

| Toothpaste against gingivitis | Human | Skaba et al. 2013 33 | |

| Oral therapeutic agent | Human | Pereira et al. 2011 30 | |

| Cancer treatment | Anti-breast cancer | Human | Xuan et al. 2014 34 |

| Antimelanoma cancer | Animals | Benguedouar et al. 2015 35 | |

| Anti-lung cancer | Human | Demir et al. 2016 36 | |

| Skin care | Acne vulgaris | Human | Ali et al. 2015 37 |

| Collagen metabolism | Animals | Olczyk et al. 2014 38 | |

| Diabetic foot ulcer | Human | Henshaw et al. 2014 39 | |

Gastrointestinal disorder

Infection with parasites usually occurs upon contact with an infected surface. The symptoms of parasitic infection of the gastrointestinal tract include abdominal pain, diarrhea, bloating, and nausea. Propolis has been reported to have several biological activities including anticancer, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities (see Figure 2). There are a few studies that reported the clinical use of propolis in the treatment of viral infections 5. In one study, the test tube effect of propolis ethanolic extract on the growth and adherence of Giardia duodenalis trophozoites was evaluated 26. Propolis was shown to inhibit growth and adherence of the trophozoites. It also promoted the detachment of these parasitic organisms. Its efficacy against giardiasis has also been reported in a clinical study whereby children and adults with giardiasis-given propolis showed a cure rate between 52% and 60%, whereas those given the conventional drug showed a 40% cure rate. Another experimental study showed that propolis has antihistaminergic, anti-inflammatory, antiacid, and anti-H. pylori activities that can be used to treat gastric ulceration 27.

Gynecological disorder

Widespread causes of indicative vaginitis are bacterial vaginosis and vulvovaginal candidiasis. The depletion of Lactobacillus spp. in the vagina is a distinguished feature of vaginal infections. The infection is accompanied by an overgrowth of vaginal pathogens such as yeast-like fungi and an elevated vaginal pH. Diabetes patients are more prone to having vaginal infections caused by Candida albicans. A study conducted on the application of 5% aqueous propolis solution resulted in an improvement in vaginal well-being 28. In addition to providing antibiotic and antimycotic actions, propolis provides early symptomatic relief due to its anesthetic properties. Thus, propolis may be used for Recurrent Vulvovaginal Candidiasis and can be an alternative option for patients who are unable to take antibiotics due to a concurrent pharmacological treatment. The effectiveness of propolis against conventional antifungal nystatin has shown satisfactory results. Propolis extract solution also show low toxicity in human cells and can be an alternative treatment for chronic vaginitis. In addition, propolis extract solution has antifungal properties and it can be used as antibiofilm material for recurrent vulvovaginal candidiasis to counteract biofilm growth of Candida albicans and resistance in antifungal drug 29.

Oral health

The oral cavity has an abundant bacterial microflora and excessive bacterial growth may lead to several conditions such as oral diseases. Studies have shown that propolis may restrict bacterial-plaque development and periodontitis-causing pathogens because of its antibacterial properties 30. Propolis solutions exert a selectively lower cytotoxic action on human gum fibroblasts compared to chlorhexidine. In addition to that, mouthwash containing propolis have shown effectiveness in healing surgical wounds. This encourages the use of propolis in solutions used as mouthwash 31. Propolis solution can also be used to disinfect toothbrushes 32. A 3% ethanolic extract of propolis toothpaste gel showed greater potency against gingivitis caused by dental plague in a group of patients 33. Propolis extracts have also helped cure halitosis, a condition where an individual experiences unpleasant breath predominantly due to poor oral hygiene. Propolis toothpaste or mouthwash is used for their ability to reduce growth of bacterial plaque and pathogenic microflora that causes gingivitis and periodontitis. Thus, propolis also plays a role as a therapeutic agent 30.

Cancer treatment

Propolis has potential as a complementary therapy for cancer. It has shown efficacy against various types, including bladder, blood, brain, breast, colon, head and neck, kidney, liver, pancreas, prostate, and skin cancers 40. Propolis could help prevent cancer progression; in various parts of the world it is considered an alternative therapy for cancer treatment 41. Propolis extracts have been found to inhibit tumor cell growth both in vitro and in vivo, including inhibition of angiogenesis, demonstrating potential for the development of new anticancer drugs 42. Various components of propolis have been shown to inhibit cancer cell growth, including cinnamic acid 43, caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) 44, quercetin 45 and chrysin 46. Propolis and its components normally have little impact on normal cells, displaying differential cytotoxicity in liver cancer, melanoma and breast cell carcinoma cell lines 47. Propolis enhances the activity of tumor necrosis factor related apoptosis inducing ligand in cancer cells 48.

A study reported that propolis has potential towards human breast cancer treatment due to its antitumor activity by inducing apoptosis on human breast cancer cells. It also exhibits low or no toxicity towards normal cells due to its selectively toxic properties against tumor cells and is believed that propolis may become a prominent agent to treat breast cancer 34. Another study investigating the effect of ethanolic extract of Algerian propolis on melanoma tumor growth has shown that galangin, a common flavonoid in propolis remarkably induced apoptosis and inhibited melanoma cells in vitro 35. Turkish propolis has also been shown to exert a selective cytotoxic action on human lung cancer cells by inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress, apoptosis, and caspase activity and by reducing the mitochondrial membrane potential. This indicates that propolis is able to minimize the cancer cell growth 36.

Skincare

Propolis is widely used in dermatological products such as creams and ointments. Its use in skin care products is based on its antiallergy, anti-inflammation, antimicrobial properties, and promotive action on collagen synthesis. A recent study comparing the effect of propolis and the conventional drug silver sulfadiazine showed that propolis notably decreased free radical activity in healing the wound beds which supported the repair process. A clinical study on acne patients using ethanolic extract propolis showed its high efficacy in the treatment of acne vulgaris 37. Propolis also shows positive collagen metabolism in the wound during the healing process by increasing the collagen content of tissues 38. A study demonstrated the use of propolis as an alternative therapy for wound healing to promote wound closure, especially under conditions such as human diabetic foot ulcer 39.

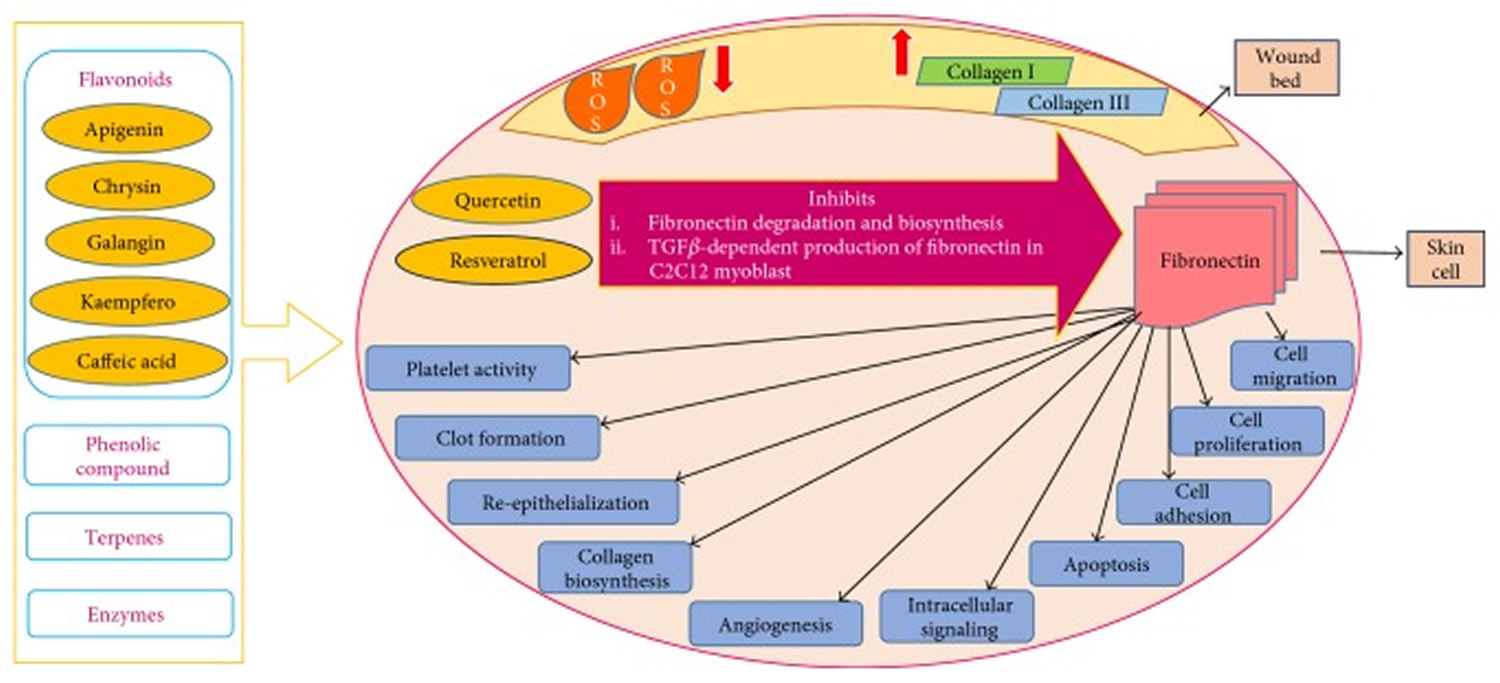

The molecular mechanisms responsible for the wound-healing activity of propolis is shown in Figure 3 below. Fibronectin is a multifunctional glycoprotein of high molecular weight, which influences the structural stability and functional properties of various organs and tissues. The fibronectin matrix and its accumulation are essential for cell migration, cell proliferation, cell differentiation, cell adhesion, apoptosis, cellular signaling, angiogenesis, collagen biosynthesis, re-epithelialization, clot formation, and platelet activity. Fibronectins are also important in the repair mechanisms for conditions such as glycoprotein intensified degradation, which leads to a defective cellular microenvironment and affliction in the structure of granulation tissues. This condition may prevent the wound from healing or inhibit the repair process. The accumulation of fibronectin in the extracellular space also modulates the secretion of other repairing components such as collagen type 1 and type 3, tenascin, laminin, and fibrillin.

Propolis has demonstrated favorable effects in the wound-healing process such as antifungal and antibacterial activities due to its components such as flavonoids, phenolic compounds, terpenes, and enzymes. It also reduces the activity of free radicals (ROS or reactive oxygen species) in the wound bed favoring the repair process. Propolis has also demonstrated great effects on collagen metabolism by increasing the amount of both type 1 and type 3 collagens in tissues. The reduction of ROS and accumulation of collagen aid in balancing the extracellular matrix and generating granulation tissues. Propolis is a potential apitherapeutic agent that is able to modify the metabolism of fibronectin by developing a fibrous network of extracellular matrix and inhibiting fibronectin disintegration. The active components in propolis such as quercetin and resveratrol inhibited fibronectin biosynthesis and TGF𝛽-dependent production of fibronectin, respectively, in C2C12 myoblasts. Both the components play important roles in regulating the expression of fibronectins. Studies have also shown that mobility and migration of epithelial cells are dependent on reduced fibronectin content in the extracellular matrix. Reduced amounts of this glycoprotein in propolis effectively treated wounds and produced granulation tissues. Therefore, the influence of propolis on fibronectin metabolism may alter the mechanism of wound healing 38.

Figure 3. Molecular mechanism targeting wound-healing activity of propolis

[Source 5 ]Antifungal action

Antifungals are used for the treatment and prevention of fungal infections. Commonly, these antifungal drugs are prescribed for the fungal infection of skin, hair, nail and oral candidiasis. Furthermore, they are used as a supportive therapy for patients suffering from denture stomatitis and added to denture tissue conditioners 49. Propolis extract shows excellent performance regarding in vitro tests against yeasts identified as onychomycosis agents. In low concentrations, propolis extract was not only found to be fungistatic but also fungicidal. Candida tropicalis was found to be the most resilient whereas the Trichosporon species were the most vulnerable yeasts. The results reinforce the importance and the potential of propolis extract as a treatment for fungal infection of the nail (onychomycosis) 50. The results of the study showed that all the yeasts tested were inhibited by low concentrations of propolis extract, including an isolate resistant to nystatin 51. Similarly, Ota et al 52 studied antifungal activity of propolis extract on 80 different strains of Candida yeast and found the yeasts showed a clear antifungal activity with the following order of sensitivity: Candida albicans > Candida tropicalis > Candida krusei > Candida guilliermondii. Recently, Siquera et al 53 assessed the fungistatic and fungicidal activity of propolis against different species of Candida using fluconazole as control. It was noted that propolis has fungistatic and fungicidal properties better than fluconazole.

Propolis has been tested against various viral disease organisms 54; initial successes have prompted research to determine the most useful components, which may be modified to produce more active and specific pharmaceuticals 55. Viruses that were controlled by propolis in animal models with suggestion for control in humans include influenza 56, herpes simplex virus type 2 (HSV-2) 57 and HIV 55. Shimizu et al. 58 evaluated three different types of propolis in ethanol extracts, using a mice model of herpes simplex virus-1 (HSV-1). Despite the chemical differences due to the different plant origins of the resins the bees used to produce the propolis (Baccharis dracunculifolia, Baccharis eriodata and Myrceugenia euosma), all three propolis extracts not only had direct anti-HSV-1 effects, but also stimulated immunological activity against intradermal HSV-1 infection in mice.

Antiviral activity of propolis has been reported for DNA and RNA viruses (poliovirus, herpes simplex virus, and adenovirus) in an in vitro model (cultured cells). The best results were obtained against poliovirus and herpes virus, with 99.9% inhibition of the latter, at a propolis concentration of 30 ug/ml 59. The propolis components chrysine and kaempferol caused a concentration-dependent reduction of intracellular replication of herpes-virus strains when host cell monolayers were infected and subsequently cultured in a drug-containing medium. Quercetin, another propolis component, had the same effect, but only at the highest concentrations tested (60 ug/mL) against various human herpes simplex virus strains, with a intracellular replication reduction of approximately 65%, while it reduced the infectivity of bovine herpes virus, human adenovirus, human coronavirus, and bovine coronavirus about 50%. The reduction was 70% in the case of rotavirus 60.

Anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory properties

There is considerable evidence that propolis can reduce and alleviate the symptoms of inflammatory diseases 61 and has immunomodulatory properties 62. However, these properties can vary according to the plant origin of the propolis, as well as the extraction process/solvent used and the inflammatory protocol (cell culture, animal models, induction by lipopolysaccharides) when the propolis extracts are tested 63. Tests with animal models have shown that propolis can reduce the levels of interleukin 6 (IL-6) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-alpha), which are key pro-inflammatory mediators, and increase the levels of the regulatory cytokine IL-10 62. Kaempferol, a propolis component, reduces IL-6, TNF-alpha, and VEGF (vascular endothelial growth factor) via the ERK-NFkB-cMyc-p21 pathway 64.

Tests on macrophage cell cultures also demonstrated that propolis inhibits the production of IL-1 beta, an important component of the inflammasome inflammatory pathway, in diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus and other autoimmune diseases 65. Although the mechanisms of action are not well elucidated, these propolis components have potential as complementary supplements in the preventive treatment of chronic inflammatory diseases 66.

Hypertension and cardiovascular disease

Propolis has demonstrated anti-hypertensive effects in rat models 67. In Cameroon, it is used in popular medicine to treat various ailments, including high blood pressure 68. Propolis has been widely used as a dietary supplement for its health benefits, including cardiovascular protective effects 69. In a human trial, consumption of propolis improved critical blood parameters, including HDL (high density lipoprotein or “good cholesterol”), glutathione (GSH) and thiobarbituric acid reactive substance (TBARS) levels, demonstrating that it could contribute to a reduced risk for cardiovascular disease 70.

Propolis reduced inflammation and prevented hyperlipidemia and metabolic syndromes in highly caloric diet induced obesity in mice. Body weight gain, visceral adipose tissue, liver and serum triglycerides, cholesterol, and non-esterified fatty acids were all reduced in the propolis fed mice 71. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester, a propolis component, is a natural anti-obesity agent 72.

Thrombosis and microthrombosis

Various types of evidence demonstrate that propolis can reduce platelet aggregation and other thrombosis-related parameters. Propolis decreased thrombotic tendencies in mice by suppressing lipopolysaccharide-induced increases in PAI-1 levels 73. Propolis downregulated platelet-derived growth factor and platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecules in low-density lipoprotein knockout mice 74. Platelet aggregation was reduced by propolis in tests on human blood in vitro 75 and in other in test tube tests 76. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE), a well-studied bioactive propolis component, inhibits collagen induced platelet activation 77.

Aging

Propolis has antioxidant properties, which could help retard or reduce aging processes 78. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE), a propolis component, increased the lifespan of Caenorhabditis elegans, a common model organism for aging studies 79. Propolis consumption protected against cognitive decline in elderly subjects (humans) exposed to high altitudes 80. Serum TGF-β1 and IL-10 levels were significantly higher in propolis-treated elderly subjects, helping reduce inflammation, which could be the mechanism of protection against cognitive decline. Activity of superoxide dismutase (SOD), a key antioxidant in men treated with propolis was increased, while malondialdehyde, a marker of oxidative stress, decreased 81. The same tendencies were detected in a diabetic rat model 82. A randomized double-blind placebo controlled clinical study of 32 patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD), demonstrated safety of the Standardized Propolis Extract (EPP-AF®) at an oral dose of 500 mg/day after administration during 12 months, with significant reduction in proteinuria and urinary MCP1 in the propolis group compared to the placebo 63, with no side effects. Propolis has the potential to reduce neurodegenerative damage through antioxidant activity, which helps protect against cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease as well as aging 83. In a mouse model of Alzheimer’s disease, coniferaldehyde, an active ingredient in propolis, had neuroprotective effects. It reduced brain beta-amyloid deposits and pathological changes in the brain, helping preserve learning and memory capacity 84.

Diabetes

Propolis was found to reduce blood glucose, blood lipids and free radicals in diabetic rats 85. It also reduced blood glucose86 and insulin resistance in diabetic rats 87. Experimental diabetic nephropathy was also prevented 88. Diabetes symptoms were reduced in a diabetic mouse model, apparently by attenuating immune activation in adipose tissues 89.

Clinical trials with diabetic patients demonstrated that propolis consumption improved antioxidant parameters 90, glycemic control 91 and the lipid profile and renal function 92. Propolis is also an antimicrobial agent with wound healing properties 93, which has proven especially useful for diabetic patients 94, who tend to develop difficult to heal wounds.

Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) is considered an anti-obesity agent with beneficial effects on inflammation and diabetes 21. CAPE reduced insulin resistance in diabetic mice and in hepatic cell culture 22. Chrysin, another component of propolis, also has antidiabetic properties 23.

Propolis dose

Clinical trials with propolis have been conducted in various regions of the world, most of them with the limitation of a lack of standardization. Berretta et al. 95 evaluated many of them; the most common dosage used was 500 mg/day for adults. Considering the case of Standardized Propolis Extract (EPP-AF®), the clinical data until now support dosages of 375 – 500 mg of propolis/day; however, non-clinical trials indicate that much higher dosages can be tolerated and may be useful 96. The dose of 500 mg/day would be equivalent to 30 drops of propolis extract (with 11% w/v of dry matter), 3 to 4 times a day, diluted in about 100 ml of water, or 3 to 4 units/day of capsules or tablets with the equivalent amount of extract. For preventive purposes, 30 drops/day or one capsule, are usually taken.

The following propolis doses have been studied in scientific research:

- Propolis by mouth:

- For diabetes: 500 mg of propolis three times per day for 8 weeks. 900 mg of propolis daily for 12 weeks. 400 mg of propolis daily for 6 months.

- For swelling (inflammation) and sores inside the mouth (oral mucositis): 80 mg of propolis (Natur Farma S.A.S.) 2-3 times daily has been used along with rinsing with bicarbonate solution.

- Propolis applied to the skin:

- For cold sores (herpes labialis): Creams or ointments containing propolis 0.5% or 3% applied to the lips 5 times per day at the start of cold sore symptoms.

- Propolis as a mouth rinse:

- For swelling (inflammation) and sores inside the mouth (oral mucositis): 5 mL of propolis 30% mouth rinse (Soren Tektoos) for 60 seconds three times daily for 7 days has been used. 10 mL of a mouth wash has been used as a gargle 3 times daily in addition to chlorhexidine mouthwash and fluconazole for 14 days. Propolis 2% to 3% (extract Standardized Propolis Extract [EPP-AF®]) has been applied to dentures 3-4 times daily for 7-14 daily.

Propolis side effects

Propolis is considered to be relatively nontoxic 97. When taken by mouth – propolis is POSSIBLY SAFE when taken by mouth appropriately. A clinical safety study was carried out at the Ribeirão Preto School of Medicine of the University of São Paulo with healthy volunteers in order to assess the safety of ingesting 375 mg/day of Standardized Propolis Extract (EPP-AF®), for five days. No adverse events were observed. The study pointed to the absence of acute toxicity after the oral use of Standardized Propolis Extract (EPP-AF®) at a dose of 375 mg daily for five days. The significant positive variation observed in the parameter HDL cholesterol needs further studies with a larger number of patients to confirm this beneficial effect on the cardiovascular system (unpublished data).

- Asthma: Some experts believe certain chemicals in propolis may make asthma worse. Avoid using propolis if you have asthma.

- Bleeding conditions: A certain chemical in propolis might slow blood clotting. Taking propolis might increase the risk of bleeding in people with bleeding disorders.

- Allergies: Do not use propolis if you are allergic to bee by-products including honey, conifers, poplars, Peru balsam, and salicylates.

- Surgery: A certain chemical in propolis might slow blood clotting. Taking propolis might increase the risk of bleeding during and after surgery. Stop taking propolis 2 weeks before surgery.

The most common and reported side effect of propolis is allergy to the resinous wax material. Propolis can cause allergic reactions, especially in people who are allergic to bees or bee products. Lozenges containing propolis can cause irritation and mouth ulcers. When applied to the skin propolis is POSSIBLY SAFE when applied to the skin appropriately. It can cause allergic reactions, especially in people who are allergic to bees or bee products. Sensitization to propolis, long recognized by apiary workers, has also been reported. Thirty-seven German beekeepers out of 1051 were allergic to propolis and showed symptoms of skin rashes after working in bee farms professionally 98. A case of eczematous dermatitis on the face after application of honey for cosmetic purposes has also been reported 99. Sensitization to propolis with cross-sensitivity to balsam of Peru, a common additive in flavoring agents, has been reported 100. Similarly, Brailo et al 98 reported a subjective case of a 20-year-old women who experienced irregular erosions covered by pseudomembranes involving the lips and oral mucosa. She used propolis-based ointments for treatment of aphthous ulcers. Moreover, Zirwas and Otto 101 claimed that with time allergic cases of propolis have increased from 0.4% to 1.4%. Adverse reactions are more common at doses greater than 15 g/day although a trial using 20 drops of an ethanolic preparation of Brazilian green propolis taken 3 times a day for 7 days resulted in reports of mild nausea and epigastric pain in some participants 97, 102.

Information regarding safety and efficacy in pregnancy and lactation is lacking 103. Furthermore, due to certain impurities in propolis, there is limited literature to recommend it in pregnant women 104. Stay on the safe side and avoid use during pregnancy. Propolis is POSSIBLY SAFE when taken by mouth while breastfeeding. Doses of 300 mg daily for up to 10 months have been used safely. Stay on the safe side and avoid higher doses when breast-feeding.

Propolis preparation may contain high levels of alcohol and may result in nausea when taken as an adjunct to metronidazole 105. Contents in propolis may interact with antiviral, anticancer, antibiotic and anti-inflammatory drugs and may manifest allergic reactions which may range from eczema, cheilitis, oral pain, labial edema and peeling of lips 106. Additionally, more research should be carried out to define the parameters of the use of propolis both in the dental and medicinal fields.

Information regarding toxicology is lacking. The median lethal dose for mice is estimated to be between 2 to 7.3 g/kg and extrapolated to a safe level in humans of propolis 70 mg/day 107.

Propolis interactions with medications

Be cautious with this combination.

- Medications changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 1A2 (CYP1A2) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Propolis might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. Taking propolis along with some medications that are changed by the liver can increase the effects and side effects of your medication. Before taking propolis, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

Some medications that are changed by the liver include clozapine (Clozaril), cyclobenzaprine (Flexeril), fluvoxamine (Luvox), haloperidol (Haldol), imipramine (Tofranil), mexiletine (Mexitil), olanzapine (Zyprexa), pentazocine (Talwin), propranolol (Inderal), tacrine (Cognex), theophylline, zileuton (Zyflo), zolmitriptan (Zomig), and others.

- Medications changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 2C19 (CYP2C19) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Propolis might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. Taking propolis along with some medications that are changed by the liver can increase the effects and side effects of your medication. Before taking propolis, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

Some medications that are changed by the liver include proton pump inhibitors including omeprazole (Prilosec), lansoprazole (Prevacid), and pantoprazole (Protonix); diazepam (Valium); carisoprodol (Soma); nelfinavir (Viracept); and others.

- Medications changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 2C9 (CYP2C9) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Propolis might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. Taking propolis along with some medications that are changed by the liver can increase the effects and side effects of your medication. Before taking propolis, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

Some medications that are changed by the liver include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as diclofenac (Cataflam, Voltaren), ibuprofen (Motrin), meloxicam (Mobic), and piroxicam (Feldene); celecoxib (Celebrex); amitriptyline (Elavil); warfarin (Coumadin); glipizide (Glucotrol); losartan (Cozaar); and others.

- Medications changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 2D6 (CYP2D6) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Propolis might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. Taking propolis along with some medications that are changed by the liver can increase the effects and side effects of your medication. Before taking propolis, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

Some medications that are changed by the liver include amitriptyline (Elavil), clozapine (Clozaril), codeine, desipramine (Norpramin), donepezil (Aricept), fentanyl (Duragesic), flecainide (Tambocor), fluoxetine (Prozac), meperidine (Demerol), methadone (Dolophine), metoprolol (Lopressor, Toprol XL), olanzapine (Zyprexa), ondansetron (Zofran), tramadol (Ultram), trazodone (Desyrel), and others.

- Medications changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 2E1 (CYP2E1) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Propolis might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. Taking propolis along with some medications that are changed by the liver can increase the effects and side effects of your medication. Before taking propolis, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

Some medications that are changed by the liver include acetaminophen, chlorzoxazone (Parafon Forte), ethanol, theophylline, and drugs used for anesthesia during surgery such as enflurane (Ethrane), halothane (Fluothane), isoflurane (Forane), and methoxyflurane (Penthrane).

- Medications changed by the liver (Cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) substrates)

Some medications are changed and broken down by the liver. Propolis might decrease how quickly the liver breaks down some medications. Taking propolis along with some medications that are changed by the liver can increase the effects and side effects of your medication. Before taking propolis, talk to your healthcare provider if you take any medications that are changed by the liver.

Some medications that are changed by the liver include lovastatin (Mevacor), clarithromycin (Biaxin), cyclosporine (Neoral, Sandimmune), diltiazem (Cardizem), estrogens, indinavir (Crixivan), triazolam (Halcion), and others.

- Herbs and supplements that might slow blood clotting

Propolis might increase the amount of time it takes for blood to clot. Taking it along with other herbs and supplements that slow blood clotting can slow blood clotting even more and could increase the risk of bleeding and bruising in some people. Some of these herbs include angelica, clove, danshen, garlic, ginger, ginkgo, Panax ginseng, and others.

- Medications that slow blood clotting (Anticoagulant / Antiplatelet drugs)

Propolis might slow blood clotting and increase bleeding time. Taking propolis along with medications that also slow clotting might increase the chances of bruising and bleeding.

Some medications that slow blood clotting include aspirin, clopidogrel (Plavix), dalteparin (Fragmin), enoxaparin (Lovenox), heparin, ticlopidine (Ticlid), warfarin (Coumadin), and others.

- Warfarin (Coumadin)

Warfarin (Coumadin) is used to slow blood clotting. Propolis might decrease the effectiveness of warfarin (Coumadin). Decreasing the effectiveness of warfarin (Coumadin) might increase the risk of clotting. Use caution in you take warfarin (Coumadin) and are starting propolis.

- Kalil, M. A., Santos, L. M., Barral, T. D., Rodrigues, D. M., Pereira, N. P., Sá, M., Umsza-Guez, M. A., Machado, B., Meyer, R., & Portela, R. W. (2019). Brazilian Green Propolis as a Therapeutic Agent for the Post-surgical Treatment of Caseous Lymphadenitis in Sheep. Frontiers in veterinary science, 6, 399. https://doi.org/10.3389/fvets.2019.00399[↩][↩]

- Castaldo S, Capasso F. Propolis, an old remedy used in modern medicine. Fitoterapia. 2002 Nov;73 Suppl 1:S1-6. doi: 10.1016/s0367-326x(02)00185-5[↩]

- Silva J.C., Rodrigues S., Feás X., Estevinho L.M. Antimicrobial activity, phenolic profile and role in the inflammation of propolis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2012;50:1790–1795. doi: 10.1016/j.fct.2012.02.097[↩]

- Gómez-Caravaca A., Gómez-Romero M., Arráez-Román D., Segura-Carretero A., Fernández-Gutiérrez A. Advances in the analysis of phenolic compounds in products derived from bees. Journal of Pharmaceutical and Biomedical Analysis. 2006;41(4):1220–1234. doi: 10.1016/j.jpba.2006.03.002[↩]

- Pasupuleti, V. R., Sammugam, L., Ramesh, N., & Gan, S. H. (2017). Honey, Propolis, and Royal Jelly: A Comprehensive Review of Their Biological Actions and Health Benefits. Oxidative medicine and cellular longevity, 2017, 1259510. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1259510[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Shehu A., Ismail S., Rohin M. A. K., Harun A., Aziz A. A., Haque M. Antifungal properties of Malaysian Tualang honey and stingless bee propolis against Candida albicans and Cryptococcus neoformans. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science. 2016;6(2):044–050[↩]

- Huang S., Zhang C.-P., Wang K., Li G. Q., Hu F.-L. Recent advances in the chemical composition of propolis. Molecules. 2014;19(12):19610–19632. doi: 10.3390/molecules191219610[↩]

- Volpi N. Separation of flavonoids and phenolic acids from propolis by capillary zone electrophoresis. Electrophoresis. 2004;25(12):1872–1878. doi: 10.1002/elps.200405949[↩]

- Lotfy M. Biological activity of bee propolis in health and disease. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2006;7(1):22–31. http://journal.waocp.org/article_24421_e27f12cfb64e899d4a0ee2f315f985bf.pdf[↩]

- Ghisalberti EL. Propolis: a review. Bee World. (1979). 60:59–84. 10.1080/0005772X.1979.11097738[↩]

- Machado BAS, Silva RPD, Barreto GDA, Costa SS, Silva DFD, Brandão HN, et al. . Chemical composition and biological activity of extracts obtained by supercritical extraction and ethanolic extraction of brown, green and red propolis derived from different geographic regions in Brazil. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0145954. 10.1371/journal.pone.0145954[↩]

- Veiga RS, Mendonca SD, Mendes PB, Paulino N, Mimica MJ, Lagareiro Netto AA, et al. . Artepillin C and phenolic compounds responsible for antimicrobial and antioxidant activity of green propolis and Baccharis dracunculifolia DC. J Appl Microbiol. (2017) 122:911–20. 10.1111/jam.13400[↩]

- Aga H, Shibuya T, Sugimoto T, Kurimoto M, Nakajima S. Isolation and identification of antimicrobial compounds in Brazilian propolis. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. (1994) 58:945–46. 10.1271/bbb.58.945[↩]

- Sforcin JM, Fernandes A, Lopes CAM, Bankova V, Funari SRC. Seasonal effect on Brazilian propolis antibacterial activity. J Ethnopharmacol. (2000) 73:243–49. 10.1016/S0378-8741(00)00320-2[↩]

- Takzaree N, Hadjiakhondi A, Hassanzadeh G, Rouini MR, Manayi A. Synergistic Effect of Honey and Propolis on Cutaneous Wound Healing in Rats. Acta Med Iran. 2016 Apr;54(4):233-9. https://acta.tums.ac.ir/index.php/acta/article/view/5023/4774[↩]

- Santos T.L.A.D., Queiroz R.F., Sawaya A.C.H.F., Lopez B.G., Soares M.B.P., Bezerra D.P., Rodrigues A.C.B.C., Paula V.F., Waldschmidt A.M. Melipona mondury produces a geopropolis with antioxidant, antibacterial and antiproliferative activities. An. Acad. Bras. Cienc. 2017;89:2247–2259. doi: 10.1590/0001-3765201720160725[↩]

- Torres A.R., Sandjo L.P., Friedemann M.T., Tomazzoli M.M., Maraschin M., Mello C.F., Santos A.R.S. Chemical characterization, antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of propolis obtained from Melipona quadrifasciata quadrifasciata and Tetragonisca angustula stingless bees. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2018;51:e7118. doi: 10.1590/1414-431×20187118[↩][↩]

- Przybyłek, I., & Karpiński, T. M. (2019). Antibacterial Properties of Propolis. Molecules (Basel, Switzerland), 24(11), 2047. https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules24112047[↩][↩]

- Pimenta H.C., Violante I.M., Musis C.R., Borges Á.H., Aranha A.M. In vitro effectiveness of Brazilian brown propolis against Enterococcus faecalis. Braz. Oral Res. 2015;29:1–6. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2015.vol29.0058[↩]

- Kędzia B., Hołderna-Kędzia E. Pinocembryna – flawonoidowy składnik krajowego propolisu o działaniu opóźniającym rozwój choroby Alzheimera. Pinocembrin—flavonoid component of domestic propolis with delaying effect of the development of Alzheimer’s disease. Post. Fitoter. 2017;18:223–228.[↩][↩]

- Shin S.H., Seo S.G., Min S., Yang H., Lee E., Son J.E., Kwon J.Y., Yue S., Chung M.Y., Kim K.H., Cheng J.X., Lee H.J., Lee K.W. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester, a major component of propolis, suppresses high fat diet-induced obesity through inhibiting adipogenesis at the mitotic clonal expansion stage. J Agric Food Chem. 2014;62(19):4306–4312. doi: 10.1021/jf405088f[↩][↩]

- Nie J., Chang Y., Li Y., Zhou Y., Qin J., Sun Z., Li H. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester (Propolis Extract) Ameliorates Insulin Resistance by Inhibiting JNK and NF-κB Inflammatory Pathways in Diabetic Mice and HepG2 Cell Models. J Agric Food Chem. 2017;65(41):9041–9053. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b02880[↩][↩]

- Ramírez-Espinosa J.J., Saldaña-Ríos J., García-Jiménez S., Villalobos-Molina R., Ávila-Villarreal G., Rodríguez-Ocampo A.N., Bernal-Fernández G., Estrada-Soto S. Chrysin Induces Antidiabetic, Antidyslipidemic and Anti-Inflammatory Effects in Athymic Nude Diabetic Mice. Molecules. 2017;23(1):67. doi: 10.3390/molecules23010067[↩][↩]

- Pasupuleti V.R., Sammugam L., Ramesh N., Gan S.H. Honey, propolis and royal jelly: A comprehensive review of their biological actions and health benefits. Oxid. Med. Cell Longev. 2017;2017:1259510. doi: 10.1155/2017/1259510[↩]

- Pamplona-Zomenhan L.C., Pamplona B.C., da Silva C.B., Marcucci M.C., Mimica L.M. Evaluation of the in vitro antimicrobial activity of an ethanol extract of Brazilian classified propolis on strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2011;42:1259–1264. doi: 10.1590/S1517-83822011000400002[↩]

- Freitas S., Shinohara L., Sforcin J., Guimarães S. In vitro effects of propolis on Giardia duodenalis trophozoites. Phytomedicine. 2006;13(3):170–175. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2004.07.008[↩][↩]

- Paulino N., Coutinho L. A., Coutinho J. R., Vilela G. C., da Silva Leandro V. P., Paulino A. S. Antiulcerogenic effect of Brazilian propolis formulation in mice. Pharmacology & Pharmacy. 2015;6(12):p. 580.[↩][↩]

- Imhof M., Lipovac M., Kurz C., Barta J., Verhoeven H. C., Huber J. C. Propolis solution for the treatment of chronic vaginitis. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 2005;89(2):127–132. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.01.033[↩][↩]

- Capoci I. R. G., Bonfim-Mendonça Pde S., Arita G. S., et al. Propolis is an efficient fungicide and inhibitor of biofilm production by vaginal Candida albicans. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2015;2015:9. doi: 10.1155/2015/287693.287693[↩][↩]

- Pereira E. M. R., da Silva J. L. D. C., Silva F. F., De Luca M. P., Lorentz T. C. M., Santos V. R. Clinical evidence of the efficacy of a mouthwash containing propolis for the control of plaque and gingivitis: a phase II study. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2011;2011:7.750249[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Jain S., Rai R., Sharma V., Batra M. Propolis in oral health: a natural remedy. World Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 2014;2(1):90–94.[↩][↩]

- Bertolini P. F. R., Biondi Filho O., Pomilio A., Pinheiro S. L., Carvalho M. S. D. Antimicrobial capacity of Aloe vera and propolis dentifrice against Streptococcus mutans strains in toothbrushes: an in vitro study. Journal of Applied Oral Science. 2012;20(1):32–37. doi: 10.1590/S1678-77572012000100007[↩][↩]

- Skaba D., Morawiec T., Tanasiewicz M., et al. Influence of the toothpaste with Brazilian ethanol extract propolis on the oral cavity health. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2013;2013:12.215391[↩][↩]

- Xuan H., Li Z., Yan H., et al. Antitumor activity of Chinese propolis in human breast cancer MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cells. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. 2014;2014:11.280120[↩][↩]

- Benguedouar L., Lahouel M., Gangloff S., et al. Annales de Dermatologie et de Vénéréologie. France: Elsevier; 2015. Algerian ethanolic extract of propolis and galangin decreased melanoma tumour progression in C57BL6 mice; p. p. S294.[↩][↩]

- Demir S., Aliyazicioglu Y., Turan I., et al. Antiproliferative and proapoptotic activity of Turkish propolis on human lung cancer cell line. Nutrition and Cancer. 2016;68(1):165–172. doi: 10.1080/01635581.2016.1115096[↩][↩]

- Ali B. M. M., Ghoname N. F., Hodeib A. A., Elbadawy M. A. Significance of topical propolis in the treatment of facial acne vulgaris. Egyptian Journal of Dermatology and Venerology. 2015;35(1):p. 29.[↩][↩]

- Olczyk P., Komosinska-Vassev K., Wisowski G., Mencner L., Stojko J., Kozma E. M. Propolis modulates fibronectin expression in the matrix of thermal injury. BioMed Research International. 2014;2014:10.748101[↩][↩][↩]

- Henshaw F. R., Bolton T., Nube V., et al. Topical application of the bee hive protectant propolis is well tolerated and improves human diabetic foot ulcer healing in a prospective feasibility study. Journal of Diabetes and Its Complications. 2014;28(6):850–857. doi: 10.1016/j.jdiacomp.2014.07.012[↩][↩]

- Patel S. Emerging Adjuvant Therapy for Cancer: Propolis and its Constituents. J Diet Suppl. 2016;13(3):245–268. doi: 10.3109/19390211.2015.1008614[↩]

- Frión-Herrera Y., Gabbia D., Scaffidi M., Zagni L., Cuesta-Rubio O., De Martin S., Carrara M. The Cuban Propolis Component Nemorosone Inhibits Proliferation and Metastatic Properties of Human Colorectal Cancer Cells. Int J Mol Sci. 2020;21(5):1827. doi: 10.3390/ijms21051827[↩]

- Watanabe M.A., Amarante M.K., Conti B.J., Sforcin J.M. Cytotoxic constituents of propolis inducing anticancer effects: a review. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2011;63(11):1378–1386. doi: 10.1111/j.2042-7158.2011.01331.x[↩]

- Akao Y M.H., Matsumoto K., Ohguchi K., Nishizawa K., Sakamoto T., Araki Y., Mishima S., Nozawa Y. Cell growth inhibitory effect of cinnamic acid derivatives from propolis on human tumor cell lines. Biol Pharm Bull. 2003;26(7):1057. doi: 10.1248/bpb.26.1057[↩]

- Chang H., Wang Y., Yin X., Liu X., Xuan H. Ethanol extract of propolis and its constituent caffeic acid phenethyl ester inhibit breast cancer cells proliferation in inflammatory microenvironment by inhibiting TLR4 signal pathway and inducing apoptosis and autophagy. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):471. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1984-9[↩]

- Orsolić N., Knezević A.H., Sver L., Terzić S., Basić I. Immunomodulatory and antimetastatic action of propolis and related polyphenolic compounds. J Ethnopharmacol. 2004;94(2–3):307–315. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2004.06.006[↩]

- Sawicka D., Car H., Borawska M.H., Nikliński J. The anticancer activity of propolis. Folia Histochem Cytobiol. 2012;50(1):25–37. doi: 10.2478/18693[↩]

- Nagaoka T., Banskota A.H., Tezuka Y., Saiki I., Kadota S. Selective antiproliferative activity of caffeic acid phenethyl ester analogues on highly liver-metastatic murine colon 26-L5 carcinoma cell line. Bioorg Med Chem. 2002;10(10):3351–3359. doi: 10.1016/s0968-0896(02)00138-4[↩]

- Szliszka E., Czuba Z.P., Domino M., Mazur B., Zydowicz G., Krol W. Ethanolic extract of propolis (EEP) enhances the apoptosis- inducing potential of TRAIL in cancer cells. Molecules. 2009;14(2):738–754. doi: 10.3390/molecules14020738[↩]

- Iqbal Z, Zafar MS. Role of antifungal medicaments added to tissue conditioners: A systematic review. Journal of Prosthodontic Research. 2016;60:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpor.2016.03.006[↩]

- Oliveira ACP, Shinobu CS, Longhini R, Franco SL, Svidzinski TIE. Antifungal activity of propolis extract against yeasts isolated from onychomycosis lesions. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz. 2006;101:493–7. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762006000500002[↩]

- Dalben-Dota K, Faria MGI, Bruschi ML, Pelloso SM, Lopes-Consolaro M, Svidzinski TIE. Antifungal activity of propolis extract against yeasts isolated from vaginal exudates. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine. 2010;16:285–90.[↩]

- Ota C, Unterkircher C, Fantinato V, Shimizu MT. Antifungal activity of propolis on different species of candida. Mycoses. 2001;44:375–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1439-0507.2001.00671.x[↩]

- Siqueira ABS, Rodriguez, Larissa Rodrigues Nolasco De Araújo , Santos RKB, Marinho RRB, Abreu S, Peixoto RF, Gurgel Gurgel, Bruno César de Vasconcelos. Antifungal activity of propolis against candidaspecies isolated from cases of chronic periodontitis. Brazilian oral research. 2015;29:1–6. doi: 10.1590/1807-3107BOR-2015.vol29.0083[↩]

- Berretta, A. A., Silveira, M., Cóndor Capcha, J. M., & De Jong, D. (2020). Propolis and its potential against SARS-CoV-2 infection mechanisms and COVID-19 disease: Running title: Propolis against SARS-CoV-2 infection and COVID-19. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie, 131, 110622. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2020.110622[↩]

- Ito J., Chang F.R., Wang H.K., Park Y.K., Ikegaki M., Kilgore N., Lee K.H. Anti-AIDS agents. 48.(1) Anti-HIV activity of moronic acid derivatives and the new melliferone-related triterpenoid isolated from Brazilian propolis. J Nat Prod. 2001;64(10):1278–1281. doi: 10.1021/np010211x[↩][↩]

- Shimizu T., Hino A., Tsutsumi A., Park Y.K., Watanabe W., Kurokawa M. Anti-influenza virus activity of propolis in vitro and its efficacy against influenza infection in mice. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2008;19(1):7–13. doi: 10.1177/095632020801900102[↩]

- Nolkemper S., Reichling J., Sensch K.H., Schnitzler P. Mechanism of herpes simplex virus type 2 suppression by propolis extracts. Phytomedicine. 2010;17(2):132–138. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2009.07.006[↩]

- Shimizu T., Takeshita Y., Takamori Y., Kai H., Sawamura R., Yoshida H., Watanabe W., Tsutsumi A., Park Y.K., Yasukawa K., Matsuno K., Shiraki K., Kurokawa M. Efficacy of Brazilian Propolis against Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 Infection in Mice and Their Modes of Antiherpetic Efficacies. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2011;2011:976196. doi: 10.1155/2011/976196[↩]

- Amoros M., Simões C.M., Girre L., Sauvager F., Cormier M. Synergistic effect of flavones and flavonols against herpes simplex virus type 1 in cell culture. Comparison with the antiviral activity of propolis. J Nat Prod. 1992;55(12):1732–1740. doi: 10.1021/np50090a003[↩]

- Debiaggi M., Tateo F., Pagani L., Luini M., Romero E. Effects of propolis flavonoids on virus infectivity and replication. Microbiologica. 1990;13(3):207–213.[↩]

- Pineros A.R., de Lima M.H.F., Rodrigues T., Gembre A.F., Bertolini T.B., Fonseca M.D., Berretta A.A., Ramalho L.N.Z., Cunha F.Q., Hori J.I., Bonato V.L.D. Green propolis increases myeloid suppressor cells and CD4(+)Foxp3(+) cells and reduces Th2 inflammation in the lungs after allergen exposure. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;252:112496. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2019.112496[↩]

- Machado J.L., Assuncao A.K., da Silva M.C., Dos Reis A.S., Costa G.C., Arruda Dde S., Rocha B.A., Vaz M.M., Paes A.M., Guerra R.N., Berretta A.A., do Nascimento F.R. Brazilian green propolis: anti-inflammatory property by an immunomodulatory activity. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2012;2012:157652. doi: 10.1155/2012/157652[↩][↩]

- Berretta A.A., Arruda C., Miguel F., Baptista N., Nascimento A., Marquele- Oliveira F., Hori J., Barud H., Damaso B., Ramos C., Ferreira R., Bastos J. Functional Properties of Brazilian Propolis: From Chemical Composition Until the Market. In: Waisundara V., editor. Superfood and Functional Food – An Overview of Their Processing and Utilization. Intech Open; London: 2017. pp. 55–98.[↩][↩]

- Da J., Xu M., Wang Y., Li W., Lu M., Wang Z. Kaempferol Promotes Apoptosis While Inhibiting Cell Proliferation via Androgen-Dependent Pathway and Suppressing Vasculogenic Mimicry and Invasion in Prostate Cancer. Anal Cell Pathol. 2019;2019:1907698. doi: 10.1155/2019/1907698[↩]

- Ramos A., Miranda J. Propolis: a review of its anti-inflammatory and healing actions. J Venom Anim Toxins Trop Dis. 2007;13(4):697–710. doi: 10.1590/S1678-91992007000400002[↩]

- Tozser J., Benko S. Natural Compounds as Regulators of NLRP3 Inflammasome-Mediated IL-1beta Production. Mediators Inflamm. 2016;2016:5460302. doi: 10.1155/2016/5460302[↩]

- Zhou H., Wang H., Shi N., Wu F. Potential Protective Effects of the Water-Soluble Chinese Propolis on Hypertension Induced by High-Salt Intake. Clin Transl Sci. 2020 doi: 10.1111/cts.12770[↩]

- Zingue S., Nde C.B.M., Michel T., Ndinteh D.T., Tchatchou J., Adamou M., Fernandez X., Fohouo F.T., Clyne C., Njamen D. Ethanol-extracted Cameroonian propolis exerts estrogenic effects and alleviates hot flushes in ovariectomized Wistar rats. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2017;17(1):65. doi: 10.1186/s12906-017-1568-8.[↩]

- Yuan W., Chang H., Liu X., Wang S., Liu H., Xuan H. Brazilian Green Propolis Inhibits Ox-LDL-Stimulated Oxidative Stress in Human Umbilical Vein Endothelial Cells Partly through PI3K/Akt/mTOR-Mediated Nrf2/HO-1 Pathway. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2019;2019:5789574. doi: 10.1155/2019/5789574[↩]

- Mujica V., Orrego R., Pérez J., Romero P., Ovalle P., Zúñiga-Hernández J., Arredondo M., Leiva E. The Role of Propolis in Oxidative Stress and Lipid Metabolism: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2017;2017:4272940. doi: 10.1155/2017/4272940[↩]

- Koya-Miyata S., Arai N., Mizote A., Taniguchi Y., Ushio S., Iwaki K., Fukuda S. Propolis prevents diet-induced hyperlipidemia and mitigates weight gain in diet-induced obesity in mice. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32(12):2022–2028. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.2022[↩]

- Rayalam S., Mills D., Azhar Y., Miller E., Wang X. Caffeic Acid Phenethyl Ester and Its Fluorinated Derivative as Natural Anti-obesity Agents (P06-089-19) Curr Dev Nutr. 2019;3(Supplement_1) doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzz031.P06-089-19[↩]

- Kitamura H. Effects of Propolis Extract and Propolis-Derived Compounds on Obesity and Diabetes: Knowledge from Cellular and Animal Models. Molecules. 2019;24(23):4394. doi: 10.3390/molecules24234394[↩]

- Daleprane J.B., Abdalla D.S. Emerging roles of propolis: antioxidant, cardioprotective, and antiangiogenic actions. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:175135. doi: 10.1155/2013/175135[↩]

- Bojić M., Antolić A., Tomičić M., Debeljak Ž., Maleš Ž. Propolis ethanolic extracts reduce adenosine diphosphate induced platelet aggregation determined on whole blood. Nutr J. 2018;17(1):52. doi: 10.1186/s12937-018-0361-y[↩]

- Zhang Y.-X., Yang T.-T., Xia L., Zhang W.-F., Wang J.-F., Wu Y.-P. Inhibitory Effect of Propolis on Platelet Aggregation In Vitro. J Healthc Eng. 2017;2017:3050895. doi: 10.1155/2017/3050895[↩]

- Hsiao G., Lee J.J., Lin K.H., Shen C.H., Fong T.H., Chou D.S., Sheu J.R. Characterization of a novel and potent collagen antagonist, caffeic acid phenethyl ester, in human platelets: in vitro and in vivo studies. Cardiovasc Res. 2007;75(4):782–792. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.05.005[↩]

- Kocot J., Kiełczykowska M., Luchowska-Kocot D., Kurzepa J., Musik I. Antioxidant Potential of Propolis, Bee Pollen, and Royal Jelly: Possible Medical Application. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2018;2018:7074209. doi: 10.1155/2018/7074209[↩]

- Havermann S., Chovolou Y., Humpf H.U., Wätjen W. Caffeic acid phenethylester increases stress resistance and enhances lifespan in Caenorhabditis elegans by modulation of the insulin-like DAF-16 signalling pathway. PLoS One. 2014;9(6) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100256[↩]

- Zhu A., Wu Z., Zhong X., Ni J., Li Y., Meng J., Du C., Zhao X., Nakanishi H., Wu S. Brazilian Green Propolis Prevents Cognitive Decline into Mild Cognitive Impairment in Elderly People Living at High Altitude. J Alzheimers Dis. 2018;63(2):551–560. doi: 10.3233/JAD-170630[↩]

- Jasprica I., Mornar A., Debeljak Z., Smolcić-Bubalo A., Medić-Sarić M., Mayer L., Romić Z., Bućan K., Balog T., Sobocanec S., Sverko V. In vivo study of propolis supplementation effects on antioxidative status and red blood cells. J Ethnopharmacol. 2007;110(3):548–554. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2006.10.023[↩]

- Sameni H.R., Ramhormozi P., Bandegi A.R., Taherian A.A., Mirmohammadkhani M., Safari M. Effects of ethanol extract of propolis on histopathological changes and anti-oxidant defense of kidney in a rat model for type 1 diabetes mellitus. J Diabetes Investig. 2016;7(4):506–513. doi: 10.1111/jdi.12459[↩]

- Ayaz M., Sadiq A., Junaid M., Ullah F., Ovais M., Ullah I., Ahmed J., Shahid M. Flavonoids as Prospective Neuroprotectants and Their Therapeutic Propensity in Aging Associated Neurological Disorders. Front Aging Neurosci. 2019;11:155. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00155[↩]

- Dong Y., Stewart T., Bai L., Li X., Xu T., Iliff J., Shi M., Zheng D., Yuan L., Wei T., Yang X., Zhang J. Coniferaldehyde attenuates Alzheimer’s pathology via activation of Nrf2 and its targets. Theranostics. 2020;10(1):179–200. doi: 10.7150/thno.36722[↩]

- El Adaouia Taleb R., Djebli N., Chenini H., Sahin H., Kolayli S. In vivo and in vitro anti-diabetic activity of ethanolic propolis extract. J Food Biochem. 2020;44 doi: 10.1111/jfbc.13267[↩]

- (Matsui T., Ebuchi S., Fujise T., Abesundara K.J., Doi S., Yamada H., Matsumoto K. Strong antihyperglycemic effects of water-soluble fraction of Brazilian propolis and its bioactive constituent, 3,4,5-tri-O-caffeoylquinic acid. Biol Pharm Bull. 2004;27(11):1797–1803. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.1797[↩]

- Aoi W., Hosogi S., Niisato N., Yokoyama N., Hayata H., Miyazaki H., Kusuzaki K., Fukuda T., Fukui M., Nakamura N., Marunaka Y. Improvement of insulin resistance, blood pressure and interstitial pH in early developmental stage of insulin resistance in OLETF rats by intake of propolis extracts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2013;432(4):650–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.029[↩]

- Abo-Salem O.M., El-Edel R.H., Harisa G.E., El-Halawany N., Ghonaim M.M. Experimental diabetic nephropathy can be prevented by propolis: Effect on metabolic disturbances and renal oxidative parameters. Pak J Pharm Sci. 2009;22(2):205–210.[↩]

- Kitamura H., Naoe Y., Kimura S., Miyamoto T., Okamoto S., Toda C., Shimamoto Y., Iwanaga T., Miyoshi I. Beneficial effects of Brazilian propolis on type 2 diabetes in ob/ob mice: Possible involvement of immune cells in mesenteric adipose tissue. Adipocyte. 2013;2(4):227–236. doi: 10.4161/adip.25608[↩]

- Gao W., Pu L., Wei J., Yao Z., Wang Y., Shi T., Zhao L., Jiao C., Guo C. Serum Antioxidant Parameters are Significantly Increased in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus after Consumption of Chinese Propolis: A Randomized Controlled Trial Based on Fasting Serum Glucose Level. Diabetes Ther. 2018;9(1):101–111. doi: 10.1007/s13300-017-0341-9[↩]

- Hesami S., Hashemipour S., Shiri-Shahsavar M.R., Koushan Y., Khadem Haghighian H. Administration of Iranian Propolis attenuates oxidative stress and blood glucose in type II diabetic patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, clinical trial. Caspian J Intern Med. 2019;10(1):48–54. doi: 10.22088/cjim.10.1.48[↩]

- Zakerkish M., Jenabi M., Zaeemzadeh N., Hemmati A.A., Neisi N. The Effect of Iranian Propolis on Glucose Metabolism, Lipid Profile, Insulin Resistance, Renal Function and Inflammatory Biomarkers in Patients with Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: A Randomized Double-Blind Clinical Trial. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):7289. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43838-8[↩]

- Picolotto A., Pergher D., Pereira G.P., Machado K.G., da Silva Barud H., Roesch-Ely M., Gonzalez M.H., Tasso L., Figueiredo J.G., Moura S. Bacterial cellulose membrane associated with red propolis as phytomodulator: Improved healing effects in experimental models of diabetes mellitus. Biomed Pharmacother. 2019;112:108640. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2019.108640[↩]

- Afkhamizadeh M., Aboutorabi R., Ravari H., Fathi Najafi M., Ataei Azimi S., Javadian Langaroodi A., Yaghoubi M.A., Sahebkar A. Topical propolis improves wound healing in patients with diabetic foot ulcer: a randomized controlled trial. Nat Prod Res. 2018;32(17):2096–2099. doi: 10.1080/14786419.2017.1363755[↩]

- Zaccaria V., Garzarella E.U., Di Giovanni C., Galeotti F., Gisone L., Campoccia D., Volpi N., Arciola C.R., Daglia M. Multi Dynamic Extraction: An Innovative Method to Obtain a Standardized Chemically and Biologically Reproducible Polyphenol Extract from Poplar-Type Propolis to Be Used for Its Anti-Infective Properties. Materials. 2019;12(22):3746. doi: 10.3390/ma12223746[↩]

- Waldesch F.G., Konigswinter B., Remagen H. Medpharm CRC Press; Boca Raton: 2003. Herbal Medicinal Products – Scientific and regulatory basis for development quality assurance and marketing authorisation.[↩]

- Castaldo S, Capasso F. Propolis, an old remedy used in modern medicine. Fitoterapia. 2002;73(suppl 1):S1-S6.12495704[↩][↩]

- Brailo V, Vucicevic Boras V, Alajbeg I, VidovicJuras D. Delayed contact sensitivity on the lips and oral mucosa due to propolis-case report. Med Oral Patol Oral Cir Bucal. 2006;11:303–4.[↩][↩]

- Matos D, Serrano P, Brandao FM. A case of allergic contact dermatitis caused by propolis-enriched honey. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;72(1):59-60.25524122[↩]

- Ting PT, Silver S. Allergic contact dermatitis to propolis. J Drugs Dermatol. 2004;3(6):685-686.15624755[↩]

- Zirwas MJ, Otto S. Toothpaste allergy diagnosis and management. The Journal of clinical and aesthetic dermatology. 2010;3:42.[↩]

- Coelho LG, Bastos EM, Resende CC, et al. Brazilian green propolis on Helicobacter pylori infection. a pilot clinical study. Helicobacter. 2007;12(5):572-574.17760728[↩]

- Ernst E. Herbal medicinal products during pregnancy: are they safe? BJOG. 2002;109(3):227-235.11950176[↩]

- Naseem M, Khurshid Z, Khan HA, Niazi F, Zohaib S, Zafar MS. Oral health challenges in pregnant women: Recommendations for dental care professionals. The Saudi Journal for Dental Research. 2016;7:138–46. doi: 10.1016/j.sjdr.2015.11.002[↩]

- Basavaiah ND, Suryakanth DB. Propolis and allergic reactions. J Pharm BioalliedSci. 2012;4:345 7406 103279. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.103279[↩]

- Czarnobilska E, Obtulowicz K, Dyga W, Spiewak R. The most important contact sensitizers in polish children and adolescents with atopy and chronic recurrent eczema as detected with the extended european baseline series. Pediatric Allergy and Immunology. 2011;22:252–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3038.2010.01075.x[↩]

- Burdock GA. Review of the biological properties and toxicity of bee propolis (propolis). Food Chem Toxicol. 1998;36(4):347-363.9651052[↩]