Prurigo pigmentosa

Prurigo pigmentosa is also known as Nagashima disease or “keto rash”, is a rare inflammatory skin disease of unknown cause that presents as a itchy truncal eruption of reticulated and symmetric macules and papules with the predilection for young Japanese females 1. Prurigo pigmentosa is characterized by a recurrent itchy erythematous macules and papules with netlike hyperpigmentation symmetrically distributed on the trunk with a predilection for the upper back, sacrum, abdomen, chest 2 and more rarely, the limbs or face 3. There are no reports of involvement of the mucous membranes, hair, or nails. Vesicular and bullous forms of prurigo pigmentosa have been reported 4. Patients may present with episodes that recur over a period of months to years, which upon resolution, leave behind a pattern of reticulated or mottled hyperpigmentation. Prurigo pigmentosa has been described in people of all ages, sex and ethnicities. However, it is more common amongst Asians, particularly young women. Women are affected twice as commonly as men. Ackerman et al 2 reported a mean age at time of diagnosis of 25 and a female to male ratio of 2:1.

Prurigo pigmentosa has increasingly been associated with ketotic states associated with diabetes, fasting and post-bariatric surgery.

In some patients, prurigo pigmentosa has been associated with systemic diseases such as Sjogren syndrome and eating disorders such as anorexia nervosa. Prurigo pigmentosa has also been described in people with atopy, as well as in pregnancy.

In 1971, Nagashima et al. 5 first described their observation of eight patients with “a peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation” and suggested the name “prurigo pigmentosa” for this condition. Following this initial description, more than 300 patients with prurigo pigmentosa have been described in the Japanese literature 6. However, fewer than 50 cases have been reported in non-Japanese patients and only 3 cases have been reported in the United States 7.

Prurigo pigmentosa responds well to tetracycline and has an excellent prognosis 8.

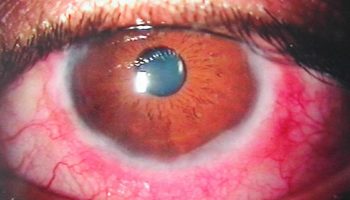

Figure 1. Prurigo pigmentosa

Footnote: Multiple erythematous papules and vesicles, some crusted, interspersed among light brown hyperpigmented macules coalescing in a reticular pattern on the upper back.

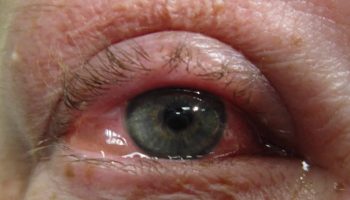

Figure 2. Prurigo pigmentosa

Footnote: Asian female presented with an undiagnosed rash on her back of a few months’ duration. It was initially red and pruritic. Topical steroids offered little relief. She was trying to take off some weight and this rash appeared within a few weeks of starting a ketogenic diet.

Prurigo pigmentosa causes

Although the pathogenesis of prurigo pigmentosa remains elusive, associations with systemic conditions including atopy 9, Helicobacter pylori infection 10, Sjogren syndrome, and adult-onset Still disease have been reported 11. The exact role of the exclusion of carbohydrates and ketosis in the development of prurigo pigmentosa has not yet been elucidated.

Several other mechanisms for prurigo pigmentosa have been proposed, including friction with clothes or a contact allergy to trichlorphenol, chromium in acupuncture needles, chrome in detergent, and nickel.

More recently, Park et al. 12 have reported 3 patients with prurigo pigmentosa who had elevated anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) titers. These patients did not have any antibodies that are more specific to lupus erythematosus. In addition, they did not have any physical signs or symptoms diagnostic of lupus. Although elevated ANA titers are a non-specific finding that can be present in up to 20 percent of the normal population, the authors suggest that autoimmunity may play a role in the pathogenesis of prurigo pigmentosa 12.

The presence of a neutrophilic infiltrate early and a lymphocytic infiltrate late in the disease suggests a reactive process. To this end, certain case reports have suggested a reaction to various allergens, including trichlorphenol 13, chromium in acupuncture needles 14, chrome in detergent 15, and nickel 16; a contact allergy to clothing has also been suggested 17. However, the majority of patients do not have a history of exposure to an allergen.

Another notable association frequently reported in the literature is with ketosis resulting from diabetes 18, diet 19, eating disorders 20, or pregnancy 21. Although several authors have reported improvement of the eruption upon resolution of ketosis 22, there is no noted association with blood glucose levels 23.

Despite the unclear etiology, Ackerman et al. 2 have described a distinct histopathologic sequence in the lesions of prurigo pigmentosa. Early lesions demonstrate a superficial perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate with papillary dermal edema, spongiosis, collections of neutrophils in the epidermis, and a few necrotic keratinocytes. In a fully developed lesion, there is a patchy lichenoid infiltrate in which lymphocytes predominate, with spongiosis intra- and subepidermal vesiculation and numerous necrotic keratinocytes. Finally, the late lesion demonstrates a lymphocytic infiltrate, mild epidermal hyperplasia, parakeratosis, scale-crust, and few to many melanophages. The lesions are negative on direct immunofluorescence.

The significance of the early neutrophilic infiltrate in the pathogenesis of prurigo pigmentosa is supported by the efficacy of the two drugs most commonly used to treat this condition: minocycline and dapsone. These agents are known to block neutrophil chemotaxis and function 24. In addition to tetracycline derivatives 25 and dapsone 26 patients have been treated with macrolide antibiotics 10 and isotretinoin 4. Topical steroids are not effective in the treatment of prurigo pigmentosa.

Prurigo pigmentosa symptoms

The clinical features of prurigo pigmentosa are:

- A pruritic (itchy) rash, which may recur

- Inflamed, red raised spots (papules) that merge to form a reticulate (network-like) pattern

- Symmetrical distribution on the trunk most often affecting the upper back, sacrum (natal cleft), abdomen and chest

- Rare involvement of the face or limbs

- Sparing of mucous membranes, hair and nails

- Reticulated hyperpigmented patches following resolution of the inflammatory phase of the rash.

Prurigo pigmentosa diagnosis

There is distinct histopathology in prurigo pigmentosa.

- Early lesion: superficial perivascular neutrophilic infiltrate, and a few necrotic keratinocytes

- Developed lesion: patchy lymphocytic infiltrate, and necrosis of numerous keratinocytes

- Late lesion: lymphocytic infiltrate, scale-crust, and melanophages

Prurigo pigmentosa treatment

The addition of carbohydrates to the diet may be beneficial if the patient is following a ketogenic diet or has undergone prolonged fasting or stomach surgery.

Dapsone and tetracycline antibiotics are effective in treating prurigo pigmentosa during the inflammatory phase of the disease. These treatments are thought to work by interfering with the movement and function of neutrophils. Recently macrolide antibiotics such as erythromycin have also been demonstrated to be helpful. It is unclear if the antibacterial action of the antibiotics is relevant.

Topical and systemic corticosteroids are not effective for prurigo pigmentosa.

To date, there are no effective treatments for the hyperpigmentation that develops in the later stages of the disease. It eventually fades.

- Prurigo pigmentosa: Report of two cases in the United States and review of the literature. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6rv324m4[↩]

- Boer A, Misago N, Wolter M, Kiryu H, Wang XD, Ackerman AB. Prurigo pigmentosa: A distinctive inflammatory disease of the skin. Am J Dermatopathol 2003 Apr;25(2):117-29.[↩][↩][↩]

- Miyakawa S, Kurihara S, Nishikawa T. Prurigo pigmentosa affecting the forehead. Dermatologica 1984;169(3):135-7.[↩]

- Requena Caballero C, Nagore E, Sanmartin O, Botella-Estrada R, Serra C, Guillen C. Vesiculous prurigo pigmentosa in a 13-year-old girl: Good response to isotretinoin. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2005 Jul;19(4):474-6.[↩][↩]

- Nagashima M, Ohshiro A, Shimizu N. A peculiar pruriginous dermatosis with gross reticular pigmentation. Jap J Dermatol 1971;81:38-9.[↩]

- Teraki Y, Nishikawa T. Skin diseases described in Japan 2004. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2005 Jan;3(1):9-25.[↩]

- Roehr P, Paller AS. A pruritic eruption with reticular pigmentation. Prurigo pigmentosa. Arch Dermatol. 1993;129:365-370.[↩]

- Prurigo pigmentosa. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/prurigo-pigmentosa[↩]

- Cota C, Donati P, Amantea A. Prurigo pigmentosa associated with an atopic diathesis in a 13-year-old girl. Pediatr Dermatol 2007 May-Jun;24(3):277-9.[↩]

- Erbagci Z. Prurigo pigmentosa in association with helicobacter pylori infection in a caucasian turkish woman. Acta Derm Venereol 2002;82(4):302-3.[↩][↩]

- Tomaru K, Nagai Y, Ohyama N, Hasegawa M, Endo Y, Tamura A, Ishikawa O. Adult-onset still’s disease with prurigo pigmentosa-like skin eruption. J Dermatol 2006 Jan;33(1):55-8.[↩]

- Park HY, Hong SP, Ahn SY, Ji JH, Choi EH, Jeon SY. Antinuclear antibodies in patients with prurigo pigmentosa: a linkage or a coincidence? Dermatology 2009;218:90-91.[↩][↩]

- Cotterill JA, Ryatt KS, Greenwood R. Prurigo pigmentosa. Br J Dermatol 1981 Dec;105(6):707-10.[↩]

- Tanii T, Kono T, Katoh J, Mizuno N, Fukuda M, Hamada T. A case of prurigo pigmentosa considered to be contact allergy to chromium in an acupuncture needle. Acta Derm Venereol 1991;71(1):66-7.[↩]

- Kim MH, Choi YW, Choi HY, Myung KB. Prurigo pigmentosa from contact allergy to chrome in detergent. Contact Dermatitis 2001 May;44(5):289-92.[↩]

- Atasoy M, Timur H, Arslan R, Ozdemir S, Gursan N, Erdem T. Prurigo pigmentosa in a patient with nickel sensitivity. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2008 May 21.[↩]

- Yamasaki R, Dekio S, Moriyasu S, Takagaki K. Three cases of prurigo pigmentosa. J Dermatol 1981;8:125-132.[↩]

- Yokozeki M, Watanabe J, Hotsubo T, Matsumura T. Prurigo pigmentosa disappeared following improvement of diabetic ketosis by insulin. J Dermatol 2003 Mar;30(3):257-8.[↩]

- Mitsuhashi Y, Suzuki N, Kawaguchi M, Kondo S. Prurigo pigmentosa on a patient with soft-drink ketosis. J Dermatol 2005 Sep;32(9):767-8.[↩]

- Leone L, Colato C, Girolomoni G. Prurigo pigmentosa in a pregnant woman. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 2007 Sep;98(3):261-2.[↩]

- Wozel G, Blasum C, Winter C, Gerlach B. Dapsone hydroxylamine inhibits the LTB4-induced chemotaxis of polymorphonuclear leukocytes into human skin: Results of a pilot study. Inflamm Res 1997 Oct;46(10):420-2.[↩]

- Ohnishi T, Kisa H, Ogata E, Watanabe S. Prurigo pigmentosa associated with diabetic ketoacidosis. Acta Derm Venereol 2000 Nov-Dec;80(6):447-8.[↩]

- Courtois JM, Dalac S, Collet E, Ladurelle AS, Lambert D. Prurigo pigmentosa. Ann Dermatol Venereol 1992;119(10):757-9.[↩]

- Schepis C, Siragusa M, Palazzo R, Ussia AF, Cavallari V. Prurigo pigmentosa treated with minocycline. Br J Dermatol 1996 Jul;135(1):158-9.[↩]

- Shannon JF, Weedon D, Sharkey MP. Prurigo pigmentosa. Australas J Dermatol 2006 Nov;47(4):289-90.[↩]

- Akoglu G, Boztepe G, Karaduman A. Prurigo pigmentosa successfully treated with low-dose isotretinoin. Dermatology 2006;213(4):331-3.[↩]