What is PTCA

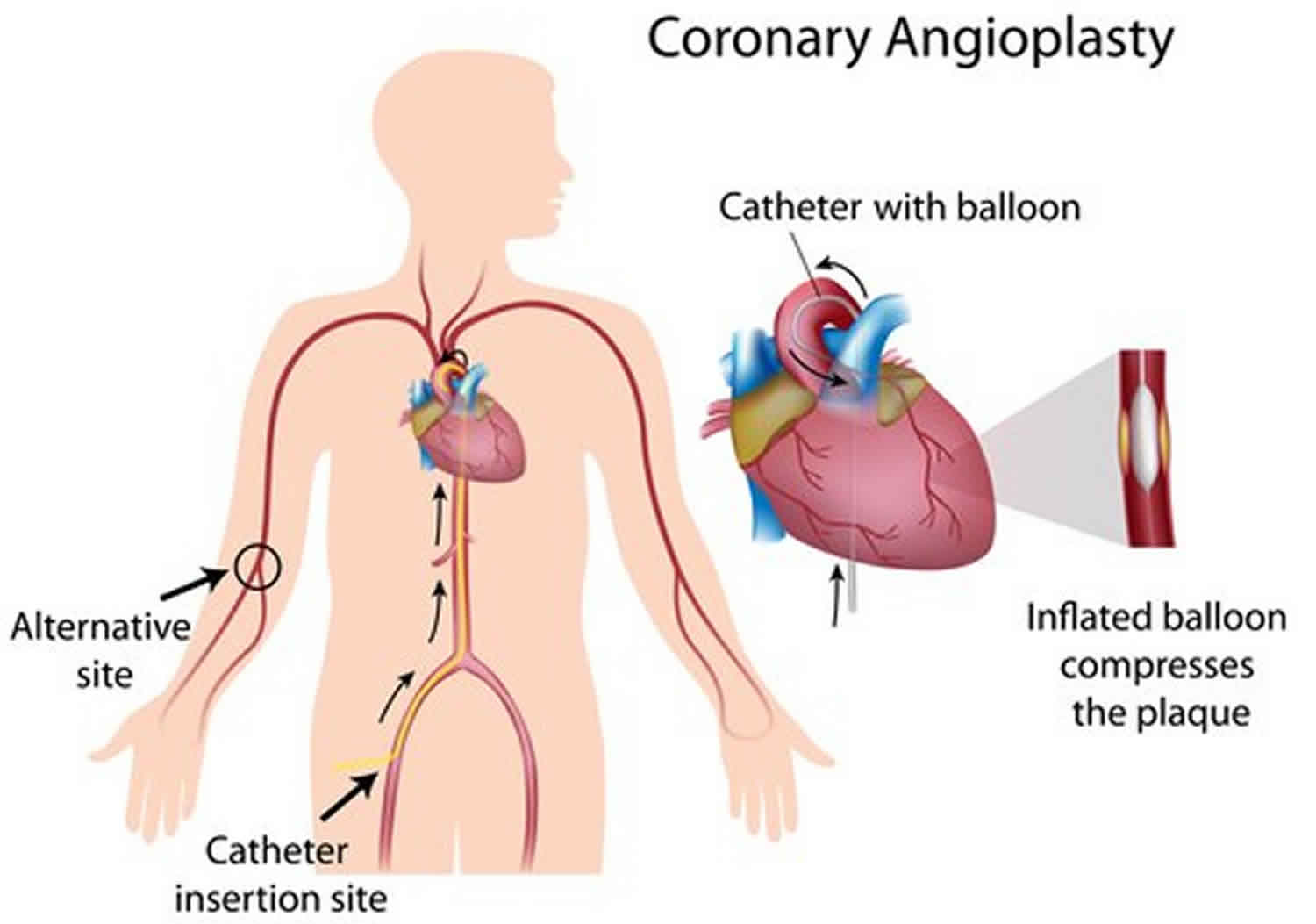

PTCA short for percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty is also called coronary angioplasty, balloon angioplasty or percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI), is a minimally invasive procedure to open up blocked coronary arteries, allowing blood to circulate unobstructed to the heart muscle 1. Angioplasty involves temporarily inserting and inflating a tiny balloon where your artery is clogged to help widen the artery. PTCA has become the method of choice to treat patients with heart attack (acute myocardial infarction) or occluded leg arteries 2.

PTCA is performed under local anesthesia and serves as an alternative to coronary artery bypass surgery (CABG). In comparison to coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG), PTCA is associated with lower morbidity and mortality, shorter convalescence and lower cost 1. It can significantly improve blood flow through the coronary arteries in about 90% of patients with relief of anginal symptoms and improvement in exercise capacity. It effectively eliminates arterial narrowing in most cases. Different modeling studies presented different conclusions regarding the cost-effectiveness of PTCA and CABG in patients of myocardial ischemia that do not respond to medical therapy 3.

PTCA procedure begins with the doctor injecting some local anesthesia into your groin area and putting a needle into the femoral artery, the blood vessel that runs down the leg. A guide wire is placed through the needle and the needle is removed. An introducer is then placed over the guide wire, after which the wire is removed. A different sized guide wire is put in its place.

Next, a long narrow tube called a diagnostic catheter is advanced through the introducer over the guide wire, into the blood vessel. This catheter is then guided to the aorta and the guide wire is removed. Once the catheter is placed in the opening or ostium of one the coronary arteries, the doctor injects dye and takes an x-ray.

If a treatable blockage is noted, the first catheter is exchanged for a guiding catheter. Once the guiding catheter is in place, a guide wire is advanced across the blockage, then a balloon catheter is advanced to the blockage site. The balloon is inflated for a few seconds to compress the blockage against the artery wall. Then the balloon is deflated.

The doctor may repeat this a few times, each time pumping up the balloon a little more to widen the passage for the blood to flow through. This treatment may be repeated at each blocked site in the coronary arteries. A device called a stent may be placed within the coronary artery to keep the vessel open. Once the compression has been performed, contrast media is injected and an x-ray is taken to check for any change in the arteries. Following this, the catheter is removed and the procedure is completed.

How you prepare

Before a scheduled PTCA procedure, your doctor will review your medical history and do a physical exam. You’ll also have an imaging test called a coronary angiogram to see if your blockages can be treated with angioplasty. A coronary angiogram helps doctors determine if the arteries to your heart are narrowed or blocked.

In a coronary angiogram, liquid dye is injected into the arteries of your heart through a catheter — a long, thin tube that’s fed through an artery from your groin, arm or wrist to arteries in your heart. As the dye fills your arteries, they become visible on X-ray and video, so your doctor can see where your arteries are blocked. If your doctor finds a blockage during your coronary angiogram, it’s possible he or she may decide to perform angioplasty and stenting immediately after the angiogram while your heart is still catheterized.

You’ll receive instructions about eating or drinking before angioplasty. Usually, you’ll need to stop eating or drinking six to eight hours before the procedure is scheduled. Your preparation may be different if you’re already staying at the hospital before your procedure.

Whether the angioplasty is pre-scheduled or done as an emergency, you’ll likely have some routine tests first, including a chest X-ray, electrocardiogram and blood tests.

Percutaneous transluminal arteriography (PCTA) is a minor procedure but can be connected with many serious complications. A Heart Team approach 4 is recommended and the ideal way to limit the complexities of this procedure. Before the intervention, the patient should have the following done:

- Preoperative evaluation including a thorough physical examination and electrocardiogram (ECG)

- Timely stress testing with either exercise or chemical stress testing if appropriate.

- Pre-procedure imaging including an echocardiogram to assess the structure and function of the heart.

- Pre-procedure evaluation by Anesthesiologist to ensure that the patient is fit for general anesthesia.

The night before your PTCA procedure, you should:

- Follow your doctor’s instructions about adjusting your current medications before angioplasty. Your doctor may instruct you to stop taking certain medications before angioplasty, such as certain diabetes medications.

- Gather all of your medications to take to the hospital with you, including nitroglycerin, if you take it.

- Take approved medications with only small sips of water.

- Arrange for transportation home. Angioplasty usually requires an overnight hospital stay, and you won’t be able to drive yourself home the next day.

PTCA vs PCI

Percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty (PTCA) also called percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

PTCA indications

Indications of PTCA depend on various factors. Patients with stable angina symptoms unresponsive to maximal medical therapy will benefit from percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) 1. PTCA helps provide relief of persistent angina symptoms despite maximal medical therapy 5. Emergency PTCA is indicated for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) suggesting 100% occlusion of the coronary artery. With acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), patients are taken directly to cath lab immediately upon presentation to help prevent further myocardial muscle damage. In non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI), or unstable angina, (known as acute coronary syndromes), patients are taken to cardiac cath lab within 24 to 48 hours.

The following are indications for PTCA if the patient is not a candidate for coronary artery bypass grafting (CABG) 2:

- Acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI)

- Non ST-elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI)

- Unstable angina

- Stable angina

- Anginal equivalent

- High-risk stress testing

PTCA contraindications

PTCA has limited contraindications 1. Patients with left main coronary heart disease are poor candidates for the PTCA procedure due to the risk of acute obstruction or spasm of the left main coronary artery during the procedure. It is also not recommended for patients with hemodynamically insignificant (less than 70%) stenosis of the coronary arteries.

The main contraindication for percutaneous transluminal arteriography is kidney dysfunction with serum creatinine greater than 3 2. The contrast dye used during the procedure puts these patients at increased risk for worsening renal function as well as an end-stage renal disease requiring future dialysis.

PTCA procedure

PTCA procedure is performed under local anesthesia. Conscious sedation is routinely given to avoid stress and calm the patient. There are multiple access points available including the radial, femoral, and ulnar arteries. Radial access is now the preferred access point as it has lower rates of complications 2. However, the femoral approach is still done quite often in patients with end-stage renal disease to preserve future access points for dialysis.

Most commonly used approach is the percutaneous femoral (Judkins) approach. Once the patient is anesthetized with a superficial injection of lidocaine to the skin, and subcutaneous tissues over the right femoral artery, a needle is inserted into the femoral artery (percutaneous access). Successful insertion of the needle is followed by insertion of a guide wire through the needle into the lumen of the blood vessel. The needle is then removed with the guide wire remaining in the vessel lumen. A sheath with introducer is placed over the guide wire and into the femoral artery. Next, the guide wire and introducer is removed, leaving the sheath in the vessel lumen. This provides easy access to the femoral artery lumen. Next, a long narrow tube, known as the “diagnostic catheter,” is advanced through the sheath with a long guidewire in the catheter lumen. The diagnostic catheter follows the guide wire and is passed retrograde through the femoral artery, iliac artery, descending aorta, over the aortic arch to the proximal ascending aorta. The guide wire is removed leaving the tip of the diagnostic catheter in the ascending aorta. The diagnostic catheter is attached to a manifold with a syringe. The manifold allows the ability to inject contrast, check inter-arterial pressure, and administer medications.

The diagnostic catheter is then manipulated into the ostium of the left main coronary artery, or right coronary artery. Contrast dye is injected, and cineangiography images are obtained in multiple views of both arteries.

Blockages less than 2 mm or smaller than the catheter are considered by many operators, not to be candidates for ballooning 2. Once the blockage is identified and determined to be safe for PTCA, a flexible guide-wire is threaded through the catheter and up to the heart. The flexible catheter is removed, and the guide-wire is advanced into the blocked coronary artery. A balloon-tipped catheter is then inserted over the guide-wire and positioned at the site of the blockage. Inflation and deflation of the catheter balloon push the artery wall out reestablishing the flow of blood in the artery. Each time the balloon is re-inflated, it blows up a little further. This procedure is done in stages to ensure the artery wall will not dissect. Once the arterial flow is re-established, the balloon-tipped catheter is removed.

In most instances, a stent is required. The balloon wire is removed and exchanged for a stent. A stent is a latticed metal scaffold that is delivered crimped over a balloon of a balloon wire. The stent is then placed in the position of the stenosis, and the balloon expanded. Once the stent is expanded, it cannot be removed from the artery. The balloon is deflated, and the stent remains in place. The stent can maintain long-term patency. Repeated injections of contrast media are utilized to check for patency of the artery.

Upon successful insertion of the stent and expansion of the vessel, the balloon wire is removed. Lastly, the PTCA guide wire is removed. During the procedure, anticoagulation is administered to prevent the formation of clots. Most coronary angioplasty procedures last between 30 minutes to 3 hours depending upon the technical difficulties of the case.

Once the process is completed, a pressure bandage is placed over the access site to prevent hemorrhage and hematoma. If femoral access were used, the patient would need to lay flat for several hours during which time the signs of bleeding or chest pain are monitored. Most patients can return home the same day as the procedure.

Types of stents

Stents are used in most coronary angioplasties.

The two main types that are currently used are:

- Drug-eluting stents: Drug-eluting stents are coated with a medicine which reduces the risk of the artery becoming narrow again after the angioplasty. Most people have this type of stent.

- Bare-metal stents: Bare-metal stents are more suitable in certain circumstances.

A new type of stent, called a bio-absorbable stent is currently being developed. These stents are made from a material which, over time, becomes absorbed by the body, allowing the artery to ‘re-form’ and work like a normal artery. At the moment they are undergoing research and are not being used routinely.

There are national guidelines to advise cardiologists about which type of stent it is best to use. These guidelines will help to decide which type of stent you will be given.

You may need to have more than one stent. This could be because:

- the narrowing is too long for one stent

- you have narrowings in different places in the same artery, or

- you have narrowings in more than one artery.

Stent placement

Most people who have angioplasty also have a stent placed in their blocked artery during the same procedure. The stent is usually inserted in the artery after it’s widened by the inflated balloon.

The stent supports the walls of your artery to help prevent it from re-narrowing after the angioplasty. The stent looks like a tiny coil of wire mesh.

Here’s what happens:

- The stent, which is collapsed around a balloon at the tip of the catheter, is guided through the artery to the blockage.

- At the blockage, the balloon is inflated and the spring-like stent expands and locks into place inside the artery.

- The stent stays in the artery permanently to hold it open and improve blood flow to your heart. In some cases, more than one stent may be needed to open a blockage.

- Once the stent is in place, the balloon catheter is removed and more images (angiograms) are taken to see how well blood flows through your newly widened artery.

- Finally, the guide catheter is removed, and the procedure is completed.

After your stent placement, you may need prolonged treatment with medications, such as aspirin or clopidogrel (Plavix) to reduce the chance of blood clots forming on the stent.

Figure 1. Coronary artery stent

Footnote: When placing a coronary artery stent, your doctor will find a blockage in your heart’s arteries (A) using cardiac catheterization techniques. A balloon on the tip of the catheter is inflated to widen the blocked artery, and a metal mesh stent is placed (B). After the stent is placed, the artery is held open by the stent, which allows blood to flow through the previously blocked artery (C).

New techniques

At some centers, cardiologists are using the following new techniques during the percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty procedure, to help them decide how best to treat you. They take just a few minutes and provide the doctors with extra information about the narrowings inside your arteries.

Intravascular ultrasound

Intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) uses sound waves to look inside the artery. A small sound probe, attached to the tip of the catheter, measures the sound waves reflecting off the artery. This provides pictures of the artery walls, and shows in more detail where the plaque is and how much there is. IVUS is often used to decide exactly where a stent should be placed, or to make sure the stent is placed in the correct position.

Optical coherence tomography

A small number of centers use a technique called optical coherence tomography (OCT), where a tiny camera at the tip of the catheter provides detailed images of the artery.

Fractional flow reserve

Sometimes the doctors use a technique called fractional flow reserve (FFR) to test the flow of blood in your arteries.

After the PTCA procedure

After the angioplasty, the catheter is removed, and a nurse or cardiologist will apply pressure over the area where it was inserted (the puncture site) for a short while, to stop any bleeding.

Over the next few hours, a nurse will regularly check your blood pressure and heart rate, the pulses in your feet or arm, and the puncture site.

If the puncture site was in your arm, you will normally be able to sit up soon after the angioplasty. If it was in your groin, you will usually have to stay in bed lying on your back for a few hours afterwards. However, a special sealing device for the puncture site is often used. This can allow you to sit up and get out of bed more quickly.

In the first few hours after the angioplasty, you may get a little chest discomfort that feels like angina. If this happens, tell your doctor or nurse about it.

If you had a non emergency PTCA procedure, you’ll probably remain hospitalized one day while your heart is monitored and your medications are adjusted. You generally should be able to return to work or your normal routine the week after angioplasty. If you needed angioplasty and stenting during a heart attack, your hospital stay and recovery period will likely be longer.

When you return home, drink plenty of fluids to help flush your body of the contrast dye. Avoid strenuous exercise and lifting heavy objects for at least a day afterward. Ask your doctor or nurse about other restrictions in activity.

Call your doctor’s office or hospital staff immediately if:

- The site where your catheter was inserted starts bleeding or swelling

- You develop pain or discomfort at the site where your catheter was inserted

- You have signs of infection, such as redness, swelling, drainage or fever

- There’s a change in temperature or color of the leg or arm that was used for the procedure

- You feel faint or weak

- You develop chest pain or shortness of breath

Blood thinners

It’s important that you closely follow your doctor’s recommendations about your treatment with blood-thinning medications — aspirin and clopidogrel or similar medications.

Most people who have undergone angioplasty with or without stent placement will need to take aspirin indefinitely. Those who have had stent placement will need a blood-thinning medication such as clopidogrel for a year or longer in some cases. If you have any questions or if you need noncardiac surgery, talk to your cardiologist before stopping any of these medications.

Going home

Many people who have a planned coronary angioplasty can go home on the same day, especially if the puncture site was in the arm rather than the groin. Others usually go home the next day. When you are making your plans for going home, try to arrange for someone to stay at home with you for the first night.

If you have had an angioplasty as an urgent or emergency treatment for acute coronary syndrome or a heart attack, how long you’ll need to stay in hospital will depend on your initial condition and diagnosis, and on how quickly you recover.

Before you leave the hospital, the team will talk to you about what you can and cannot do when you get home. They will also tell you about what medicines you need to take and when your follow-up appointment will be.

While you’re in hospital, a member of the cardiac rehabilitation team may visit you. They will talk to you about your recovery and how to get back to your usual activities, and offer advice on how you can improve your diet and lifestyle. They’ll also give you information on how to join a cardiac rehabilitation programme after you go home.

When you get home, keep an eye on the area where the catheter was inserted. You can expect to have some bruising and tenderness. But contact your doctor if you get any new swelling, or if the bruising becomes very widespread, or if the area becomes hard and painful. If your leg or arm changes colour, or becomes numb or cool to touch, get medical attention straight away. In very rare cases, there may be significant bleeding from the artery. If this happens, apply firm pressure and call your local emergency services number.

You may feel tired after having your coronary angioplasty, but most people find that they’re back to normal within a few days. Gradually increase your activity to get back to what you were able to do before the angioplasty. But avoid doing any strenuous or demanding activities, like heavy lifting, for at least a week, or longer if your doctor says so.

If you were suffering from frequent angina before the angioplasty, you may be able to do more than you were doing before.

If you’ve had a heart attack, it will take longer for you to recover and you’ll need to avoid strenuous or demanding activities for longer.

Driving

If you have an ordinary driving licence to drive a car or motorcycle, you should not drive for at least one week after having a successful angioplasty. However, if you’ve also had a heart attack, the time needed before you can start driving again depends on the nature of your heart attack. Most people will need to avoid driving for at least four weeks, but some people may be allowed to drive after a week. Check this with your doctor or cardiac rehab team.

If you have a bus, coach or truck licence

If you have one of these licences, you should not drive for at least six weeks after your angioplasty. You will need to have further tests before you can drive a bus,

coach or truck again.

PTCA risks

Although percutaneous coronary angioplasty is a less invasive way to open clogged arteries than bypass surgery is, the procedure still carries some risks.

The most common percutaneous coronary angioplasty risks include:

- Re-narrowing of your artery (restenosis). With angioplasty alone — without stent placement — restenosis happens in about 30 percent of cases. Stents were developed to reduce restenosis. Bare-metal stents reduce the chance of restenosis to about 15 percent, and the use of drug-eluting stents reduces the risk to less than 10 percent.

- Blood clots. Blood clots can form within stents even after the procedure. These clots can close the artery, causing a heart attack. It’s important to take aspirin, clopidogrel (Plavix), prasugrel (Effient) or another medication that helps reduce the risk of blood clots exactly as prescribed to decrease the chance of clots forming in your stent. Talk to your doctor about how long you’ll need to take these medications. Never discontinue these medications without discussing it with your doctor.

- Bleeding. You may have bleeding in your leg or arm where a catheter was inserted. Usually this simply results in a bruise, but sometimes serious bleeding occurs and may require a blood transfusion or surgical procedures.

Other rare risks of PTCA procedure include:

- Heart attack. Though rare, you may have a heart attack during the procedure.

- Coronary artery damage. Your coronary artery may be torn or ruptured (dissected) during the procedure. These complications may require emergency bypass surgery.

- Kidney problems. The dye used during angioplasty and stent placement can cause kidney damage, especially in people who already have kidney problems. If you’re at increased risk, your doctor may take steps to try to protect your kidneys, such as limiting the amount of contrast dye and making sure that you’re well-hydrated during the procedure.

- Stroke. During angioplasty, a stroke can occur if plaques break loose when the catheters are being threaded through the aorta. Blood clots also can form in catheters and travel to the brain if they break loose. A stroke is an extremely rare complication of coronary angioplasty, and blood thinners are used during the procedure to reduce the risk.

- Abnormal heart rhythms. During the procedure, the heart may beat too quickly or too slowly. These heart rhythm problems are usually short-lived, but sometimes medications or a temporary pacemaker is needed.

Reactions to the dye

It’s normal to get a warm, flushing feeling when the radio-opaque dye is injected during a coronary angioplasty. This lasts only a short time. A small number of people may have an allergic reaction to the dye. It’s rare to have a serious reaction. However, if you’ve ever had any test that uses radio-opaque dye and you’ve had an allergic reaction to it, no matter how small, tell the cardiologist and nurse before you have your angioplasty.

Radiation

Having a coronary angioplasty means that you are exposed to a small amount of radiation. However, if you’ve been told that you need an angioplasty, the benefits of having the procedure are likely to be greater than the risks from the radiation.

PTCA complications

PTCA is widely practiced and has risks, but major procedural complications are rare. The mortality rate during angioplasty is 1.2% 6. People older than the age of 65, with kidney disease or diabetes, women and those with massive heart disease are at a higher risk for complications. Possible complications include hematoma at the femoral artery insertion site, pseudoaneurysm of the femoral artery, infection of skin over femoral artery, embolism, stroke, kidney injury from contrast dye, hypersensitivity to dye, vessel rupture, coronary artery dissection, bleeding, vasospasm, thrombus formation, and acute heart attack. There is a long-term risk of re-stenosis of the stented vessel.

Multiple studies following PTCA have revealed an increased risk of new-onset arrhythmias, angina, aneurysm, arteritis, coronary artery aneurysm, congestive heart failure, renal failure, groin infection, myocardial infarction, hemorrhage, hematoma, thrombus, pancreatitis, and death to be possible complications of percutaneous transluminal coronary angioplasty 7. In 1994 Carey and colleagues studied the need for emergency surgical intervention following PCTA complications and found that postoperative complications were higher in the former PCTA group with stroke and arrhythmias 8. In 1996, White and colleagues 9 published a study that showed a strong association between coronary thrombus and post-operative complications following PTCA.

PTCA results

Percutaneous coronary angioplasty greatly increases blood flow through the previously narrowed or blocked coronary artery. Your chest pain generally should decrease, and you may be better able to exercise.

Having percutaneous coronary angioplasty and stenting doesn’t mean your heart disease goes away. You’ll need to continue healthy lifestyle habits and take medications as prescribed by your doctor.

If your symptoms return, such as chest pain or shortness of breath, or if other symptoms similar to those you had before your procedure recur, contact your doctor. If you have chest pain at rest or pain that doesn’t respond to nitroglycerin, call your local emergency medical help.

To keep your heart healthy after angioplasty, you should:

- Quit smoking

- Lower your cholesterol levels

- Maintain a healthy weight

- Control other conditions, such as diabetes and high blood pressure

- Get regular exercise

Successful angioplasty also means you might not have to undergo a surgical procedure called coronary artery bypass surgery. In a bypass, an artery or a vein is removed from a different part of your body and sewn to the surface of your heart to take over for the blocked coronary artery. This surgery requires an incision in the chest, and recovery from bypass surgery is usually longer and more uncomfortable.

- Malik TF, Tivakaran VS. Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Angioplasty (PTCA) [Updated 2018 Dec 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535417[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Brown KN, Gupta N. Percutaneous Transluminal Coronary Arteriography. [Updated 2019 Feb 22]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538158[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Osnabrugge RL, Magnuson EA, Serruys PW, Campos CM, Wang K, van Klaveren D, Farooq V, Abdallah MS, Li H, Vilain KA, Steyerberg EW, Morice MC, Dawkins KD, Mohr FW, Kappetein AP, Cohen DJ., SYNTAX trial investigators. Cost-effectiveness of percutaneous coronary intervention versus bypass surgery from a Dutch perspective. Heart. 2015 Dec;101(24):1980-8[↩]

- Sanchez CE, Dota A, Badhwar V, Kliner D, Smith AJ, Chu D, Toma C, Wei L, Marroquin OC, Schindler J, Lee JS, Mulukutla SR. Revascularization heart team recommendations as an adjunct to appropriate use criteria for coronary revascularization in patients with complex coronary artery disease. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2016 Oct;88(4):E103-E112.[↩]

- Pursnani S, Korley F, Gopaul R, Kanade P, Chandra N, Shaw RE, Bangalore S. Percutaneous coronary intervention versus optimal medical therapy in stable coronary artery disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2012 Aug 01;5(4):476-90.[↩]

- Movahed MR, Hashemzadeh M, Jamal MM, Ramaraj R. Decreasing in-hospital mortality of patients undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention with persistent higher mortality rates in women and minorities in the United States. J Invasive Cardiol. 2010 Feb;22(2):58-60.[↩]

- White HD, Reynolds HR, Carvalho AC, Pearte CA, Liu L, Martin CE, Knatterud GL, Džavík V, Kruk M, Steg PG, Cantor WJ, Menon V, Lamas GA, Hochman JS. Reinfarction after percutaneous coronary intervention or medical management using the universal definition in patients with total occlusion after myocardial infarction: results from long-term follow-up of the Occluded Artery Trial (OAT) cohort. Am. Heart J. 2012 Apr;163(4):563-71[↩]

- Carey JA, Davies SW, Balcon R, Layton C, Magee P, Rothman MT, Timmis AD, Wright JE, Walesby RK. Emergency surgical revascularisation for coronary angioplasty complications. Br Heart J. 1994 Nov;72(5):428-35[↩]

- White CJ, Ramee SR, Collins TJ, Escobar AE, Karsan A, Shaw D, Jain SP, Bass TA, Heuser RR, Teirstein PS, Bonan R, Walter PD, Smalling RW. Coronary thrombi increase PTCA risk. Angioscopy as a clinical tool. Circulation. 1996 Jan 15;93(2):253-8.[↩]