Pyonephrosis

Pyonephrosis is a term given to an infection of the kidney with pus in the upper collecting system which can progress to obstruction 1. Similar to an abscess, pyonephrosis is typically associated with fever, chills, and flank pain, although some patients may be asymptomatic 2. Pyonephrosis may be caused by a broad spectrum of pathologic conditions involving either an ascending infection of the urinary tract or the hematogenous spread of a bacterial pathogen 3.

Pyonephrosis is uncommon in adults and rare in children, and it is thought to be extremely rare in neonates. However, pyonephrosis has been reported in several neonates 4 and adults, making it clear that the condition may develop in any age group.

Risk factors for pyonephrosis include immunosuppression due to medications (eg, steroids), disease (eg, diabetes mellitus, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]), and any anatomic urinary tract obstruction (eg, stones, tumors, ureteropelvic junction obstruction, pelvic kidney, horseshoe kidney) 5.

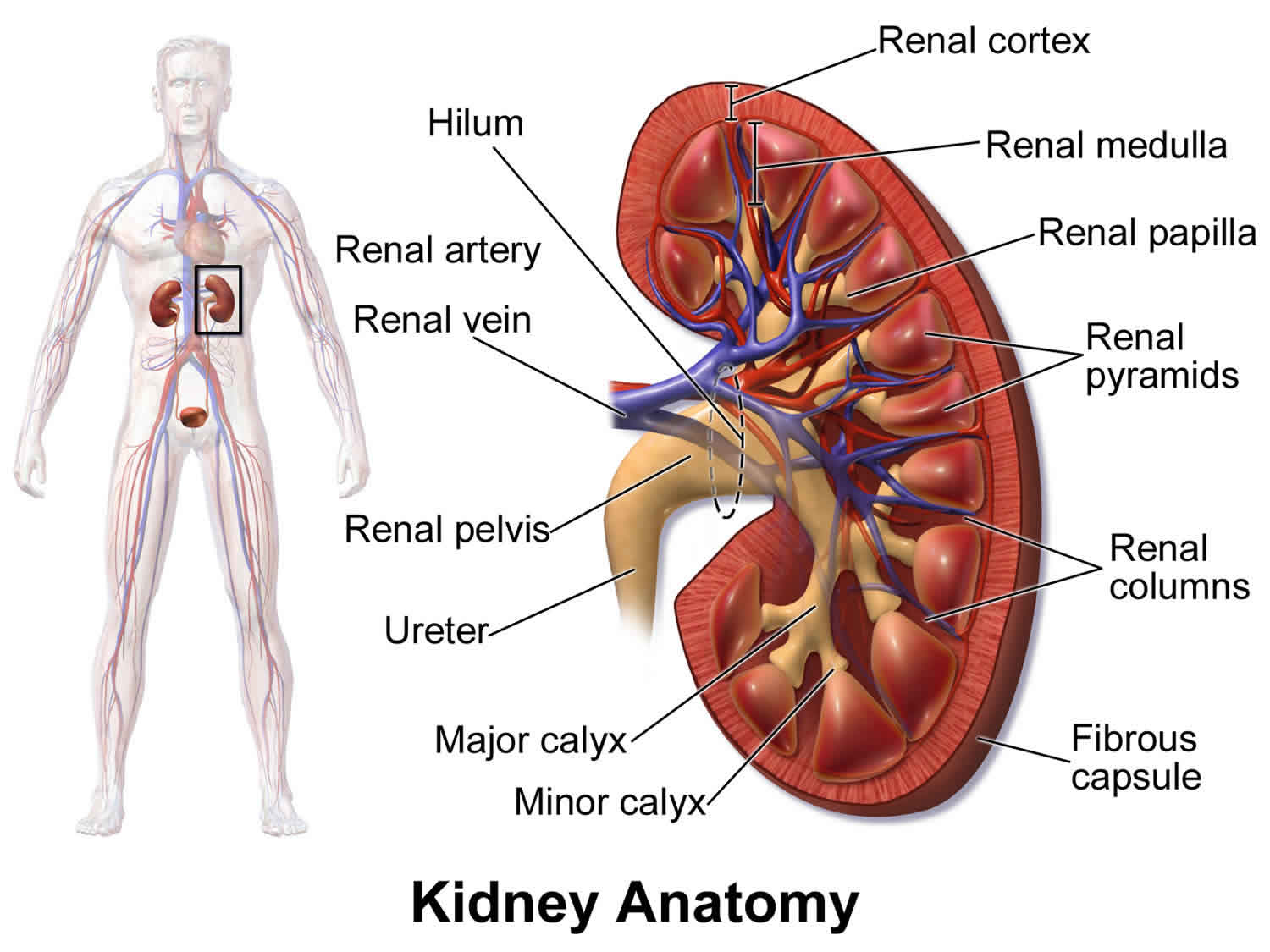

In pyonephrosis, purulent exudate—consisting of inflammatory cells, infectious organisms, and a necrotic, sloughed urothelium—collects in a hydronephrotic collecting system and forms an abscess. The exudate becomes walled off and protected from the body’s natural immune system and from antibiotics. If not recognized and treated promptly, this infectious process may progress, often resulting in clinical deterioration of the patient with urosepsis, which can occur swiftly.

The diagnosis of pyonephrosis is suspected when the clinical symptoms of fever and flank pain are combined with the radiologic evidence of urinary tract obstruction 6.

Emergent insertion of a percutaneous nephrostomy to drain the infected collecting system is usually performed after review and close collaboration with a urologist.

Pyonephrosis causes

Upper urinary tract infection (UTI) in combination with obstruction and hydronephrosis may lead to pyonephrosis. This may progress to renal and perirenal abscesses 7.

Immunocompromised patients and those who are treated with long-term antibiotics are at an increased risk for fungal infections. When fungus balls are present, they may obstruct the renal pelvis or the ureter, resulting in pyonephrosis. Xanthogranulomatous pyelonephritis, a clinical condition consisting of upper renal calculus and infection, has been reported to progress to pyonephrosis when obstruction is present. Several case reports indicate that obstruction from tumors, such as in transitional cell carcinoma, may also cause pyonephrosis 8. The disease process of pyonephrosis consists of 2 parts: infection and obstruction.

Infection

As reported in the current literature, multiple infectious agents have been isolated in patients with pyonephrosis. These include the following, in decreasing order of incidence:

- Escherichia coli

- Enterococcus species

- Candida species and other fungal infections

- Enterobacter species

- Klebsiella species

- Proteus species

- Pseudomonas species

- Bacteroides species

- Staphylococcus species

- Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) 9

- Salmonella species

- Tuberculosis (causes both infection and strictures)

Obstruction

The cause of the obstruction may relate to any of the following factors:

- Stones and staghorn calculi – In as many as 75% of patients

- Fungus balls

- Metastatic retroperitoneal fibrosis – e.g., renal tumors, testicular cancer, colon cancer

- Obstructing transitional cell carcinoma 10

- Mucinous adenocarcinoma of the renal pelvis 11

- Pregnancy

- Ureteropelvic junction obstruction

- Obstructing ureterocele

- Ureterovesical junction obstruction

- Chronic stasis of urine and hydronephrosis secondary to neurogenic bladder

- Ureteral strictures

- Papillary necrosis

- Tuberculosis

- Duplicated kidneys with obstructive components

- Ectopic ureter with ureterocele 12

- Neurogenic bladder

- Other, rare causes, such as sciatic hernias that cause ureteral obstruction

Pyonephrosis symptoms

Patients with pyonephrosis may present with clinical symptoms ranging from asymptomatic bacteruria (15%) to frank sepsis. Maintain a high index of suspicion when examining a patient with a history of fever, flank pain, evidence of a urinary tract infection, and obstruction or hydronephrosis. On physical examination, a palpable abdominal mass may be associated with the hydronephrotic kidney. Rarely, the infected hydronephrotic kidney may rupture spontaneously into the peritoneal cavity, causing some patients to present with diffuse peritonitis and sepsis 13.

Pyonephrosis complications

Sepsis is the most common complication in the perioperative period when treatment is delayed.

Generalized peritonitis can result from a rupture of the pyonephrotic kidney. In 1996, Hendaoui et al 14 reported the first case of a splenic abscess that developed from a ruptured pyonephrosis after the development of generalized peritonitis. Other occurrences of intraperitoneal and retroperitoneal spontaneous rupture have been reported by Sugiura et al, in 2004 15; Chung et al, in 2009 8 and Quaresima et al, in 2011 13, making it possibly much more common than originally thought.

Fistulas may develop and can be associated with peritonitis 16. Renocolonic, renoduodenal 17 and renocutaneous fistulas are the most common; therefore, suspect these in patients who manifest continued electrolyte disorders, diarrhea, and recurrent urinary tract infections after resolution of pyonephrosis.

Other rare complications include pneumoperitoneum from lithogenic pyonephrosis, nephrobronchial fistula, renal vein thrombosis, psoas abscess and/or perinephric abscess, and rhabdomyolysis.

Delay in diagnosis and treatment may result in a loss of renal function from parenchymal damage.

Perinephric hematomas, blood transfusions, and the need for nephrostomy tube revision are complications of percutaneous drainage. If a nephrectomy must be performed in the future, long-term nephrostomy tubes are reported to increase the risk of a postoperative wound infection 18.

Pyonephrosis diagnosis

A complete blood cell count (CBC) with a manual differential, serum chemistry with blood urea nitrogen (BUN) and creatinine, a urinalysis with culture, and blood cultures are indicated in the initial workup of a patient with suspected pyonephrosis 3.

A urine culture of the fluid above the obstruction must be obtained in order to guide antibiotic therapy. A culture specimen may be obtained from an open-ended catheter that has been advanced above the obstruction during stent placement. Cultures should also be obtained from the percutaneous tube at the time of nephrostomy placement if this course of action is chosen.

Leukocytosis and bacteruria may be present; however, they are not specific for pyonephrosis and may be due to other causes (eg, pyelonephritis, uncomplicated urinary tract infections).

Pyuria, while often present in pyonephrosis, is nonspecific. Bacteruria, fever, pain, and leukocytosis can be absent in 30% of patients with pyonephrosis.

C-reactive protein (CRP) value has been shown to help in the diagnosis of pyonephrosis. In a study of 110 patients with renal colic, CRP levels greater than 28 mg/L indicated the need for emergent drainage, with good reliability 19. However, in a systematic review the evidence for use of CRP testing to differentiate pyelonephritis from cystitis in children with urinary tract infections did not support routine use in clinical practice 20.

Lertdumrongluk et al investigated the use of urine heparin-binding protein, a cytokine released from activated neutrophils, for the diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis and concluded that urine heparin-binding protein is a valid adjunctive diagnostic tool for aiding clinicians in making rapid treatment decisions for acute pyelonephritis 21.

Aspiration

Aspiration of the collecting system with CT scan or ultrasonographic guidance, with Gram stain and culture of the fluid, provides a definitive diagnosis of pyonephrosis. Sending the culture for aerobic, anaerobic, and fungal pathogens is important. If clinically indicated, perform acid-fast stain and send cultures for tuberculosis testing.

Imaging studies

Routine radiographic imaging of patients with uncomplicated urinary tract infections is not generally advocated. However, appropriate radiographic studies are beneficial in diagnosing pyonephrosis, emphysematous pyelonephritis, and renal and/or perirenal abscess when patients do not improve rapidly with appropriate antibiotics 22.

Ultrasonography

The sensitivity of renal ultrasonography for differentiating hydronephrosis from pyonephrosis is 90%, and the specificity is 97% 23.

Ultrasonographic findings suggestive of pyonephrosis include the presence of hydronephrosis in conjunction with hyperechoic debris in the collecting system (see image below). The presence of debris and layering of low-amplitude echoes in the hydronephrotic kidney indicate pyonephrosis. These low-level echogenic foci in the collecting system remain the most consistent finding in pyonephrosis. These findings are specific enough that their absence excludes pyonephrosis with a high degree of accuracy 24.

Echogenic gas is rarely demonstrated. Intrarenal gas appears as “dirty shadows.” If echogenic gas is present, assume that the patient has a severe infection and possible renal injury suggestive of emphysematous pyelonephritis.

Ultrasonography does have drawbacks 25. For example, it may not always differentiate hydronephrosis from early pyonephrosis. In these cases, consider conducting an ultrasonographically guided aspiration of the hydronephrotic fluid for microscopic examination to establish the diagnosis.

Computed tomography

CT scanning is extremely helpful in diagnosing pyonephrosis. Advantages of CT scanning include definitive delineation of the obstruction, the function of the kidney, and the severity of hydronephrosis, as well as the presence of other abdominal pathologies, including metastatic cancer, retroperitoneal fibrosis, and renal stones that are not visible on the sonogram 26.

Diagnostic criteria for pyonephrosis on CT scanning include the following 27:

- Increased wall thickness of the renal pelvis of ≥2 mm

- The presence of renal pelvic contents and debris

- Parenchymal and perirenal findings, such as perirenal fat stranding.

- Parenchymal or perinephric inflammatory changes

- Dilatation and obstruction of the collecting system

- Higher than usual attenuation values of the fluid within the renal collecting system

- Gas-fluid levels in the intrarenal collecting system

- Layering of contrast material above / anterior to the purulent fluid on excretory studies

A caveat to CT evaluation is that it is often difficult to distinguish simple hydronephrosis from pyonephrosis by fluid attenuation measurements.

The presence of pyonephrosis during episodes of acute pyelonephritis has been described as a negative prognostic indicator for patients who do not respond appropriately to treatment for the pyelonephritis. Kim et al 28 developed a scoring system for CT scanning of patients admitted with acute pyelonephritis that includes the presence or absence of pyonephrosis. Increased scores on admission indicate more severe illness, thus possibly requiring surgical treatment or other intervention for the infected hydronephrosis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI may demonstrate features similar to those seen on CT. Some promising preliminary work has been done with both diffusion-weighted imaging and apparent apparent diffusion coefficient maps in an attempt to distinguish hydronephrosis from pyonephrosis, but these techniques require further investigation 29.

Renal nuclear scanning

Renal nuclear scanning is not particularly helpful in the immediate diagnostic workup of pyonephrosis. Acutely, scans may exhibit prolonged cortical uptake with delayed excretion of radionuclide similar to that observed in acute obstruction. The image may also be similar to that observed in acute pyelonephritis, with defects in uptake of the radiopharmaceutical that can be unifocal, multifocal, or diffuse. These defects often resolve with resolution of the infection; however, persistence in follow-up renal nuclear scans may indicate permanent damage to the renal cortex 30.

Renal nuclear scanning may be helpful when a kidney is believed to be nonfunctional on any imaging study during the acute phase of pyonephrosis. Performing follow-up nuclear imaging studies is prudent after resolution of the infection to establish the function of the involved kidney. If a kidney is proven to be nonfunctional after resolution of infection and treatment of the etiology of the obstruction, then nephrectomy may be indicated to prevent further episodes of pyonephrosis.

Antegrade nephrostography

This test may be extremely helpful in determining the etiology of the obstruction associated with pyonephrosis and in planning further treatment strategies.

As with any invasive procedure, nephrostography should be delayed until the patient is stable, on antibiotics, and afebrile for 1-2 weeks after placement of a nephrostomy tube.

Further imaging tests

When a definitive anatomic abnormality, such as the presence of a stone or tumor, cannot be determined, further imaging studies and tests may be needed to establish the cause of the pyonephrosis.

These tests may include voiding cystourethrography, to exclude vesicoureteral reflux; multichannel urodynamics, to establish a possible neurogenic bladder with urine stasis; and serial renal ultrasonography, to document resolution of hydronephrosis after treatment.

Pyonephrosis treatment

Pyonephrosis is a surgical emergency and needs immediate intervention. Emergent insertion of a percutaneous nephrostomy to drain the infected collecting system is usually performed after review and close collaboration with a urologist.

With the advent of ultrasonography and computed tomography (CT) scanning, drainage—either percutaneously or retrograde with a ureteral stent—has become the mainstay of treatment 31. Drainage has low morbidity and mortality rates and an excellent outcome. Drainage guided by CT scan or ultrasonography significantly decreases the need for nephrectomy, resulting in renal preservation.

In selected healthy, stable patients, consider retrograde decompression with a stent as an option. This avoids placement of a percutaneous nephrostomy tube and allows internalization of the drainage catheter. However, it does not allow for the antegrade medication infusion or the treatment of obstruction that is sometimes needed with funguria and infected stones 32.

When indicated, laparoscopic nephrectomy for inflammatory kidney disorders such as pyonephrosis has been shown to be safe and effective. The largest risk to the patient in these cases is typically the need to convert to an open procedure (28%) and wound infections 33.

Pyonephrosis prognosis

The prognosis of pyonephrosis is good in most patients who receive prompt diagnosis and treatment. Most infectious processes resolve within 24-48 hours and significantly improve after either nephrostomy or retrograde stent drainage of the infection. If pyonephrosis is recognized and treated promptly, recovery of the affected renal unit is rapid. Long-term complications are rare when pyonephrosis is managed promptly; however, injury to the functional renal unit, abscesses, fistulas, and scarring may occur when definitive therapy is delayed.

Patients with pyonephrosis that is not recognized early may rapidly deteriorate and develop septic shock. In addition to the morbidity and mortality associated with septic shock, potential complications of delayed diagnosis and treatment of pyonephrosis include irreversible damage to the kidneys, with the possible need for nephrectomy. Even in the modern era of antibiotics, adequately controlling an overwhelming infection in an obstructed renal unit without surgical intervention may be impossible. If the diagnosis is delayed, unduly prolonged illness and death may result.

- Pyonephrosis: sonography in the diagnosis and management. American Journal of Roentgenology. 1981;137: 939-943. 10.2214/ajr.137.5.939[↩]

- Pyonephrosis. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/440548-overview[↩]

- St Lezin M, Hofmann R, Stoller ML. Pyonephrosis: diagnosis and treatment. Br J Urol. 1992 Oct. 70(4):360-3.[↩][↩]

- Sharma S, Mohta A, Sharma P. Neonatal pyonephrosis–a case report. Int Urol Nephrol. 2004. 36(3):313-5.[↩]

- Wah TM, Weston MJ, Irving HC. Lower moiety pelvic-ureteric junction obstruction (PUJO) of the duplex kidney presenting with pyonephrosis in adults. Br J Radiol. 2003 Dec. 76(912):909-12.[↩]

- Pyonephrosis: imaging and intervention. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1983 Oct;141(4):735-40. DOI:10.2214/ajr.141.4.735[↩]

- Sugiura S, Ishioka J, Chiba K, et al. [A case report of splenic abscesses due to pyonephrosis]. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2004 Apr. 50(4):265-7.[↩]

- Chung SD, Lai MK, Chueh SC, Wang SM, Yu HJ. An unusual cause of pyonephrosis and intra-peritoneal abscess: ureteral urothelial carcinoma. Int J Infect Dis. 2009 Jan. 13(1):e39-40.[↩][↩]

- Baraboutis IG, Koukoulaki M, Belesiotou H, Platsouka E, Papastamopoulos V, Kontothanasis D, et al. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus as a cause of rapidly progressing pyelonephritis with pyonephrosis, necessitating emergent nephrectomy. Am J Med Sci. 2009 Sep. 338(3):233-5.[↩]

- Jain KA. Transitional cell carcinoma of the renal pelvis presenting as pyonephrosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2007 Jul. 26(7):971-5.[↩]

- Bal A, Aulakh R, Mohan H, Bawa AS. Mucinous adenocarcinoma of the renal pelvis presenting as pyonephrosis: a case report. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2007 Apr. 50(2):336-7.[↩]

- Martín MS, García-Ripoll TJ, Ruíz SA, Rodríguez GV, Ferro RJ, del Busto FE. [Ectopic ureter as cause of pyonephrosis and urinary incontinence]. Actas Urol Esp. 2008 Feb. 32(2):256-60.[↩]

- Quaresima S, Manzelli A, Ricciardi E, Petrou A, Brennan N, Mauriello A, et al. Spontaneous intraperitoneal rupture of pyonephrosis in a patient with unknown kidney carcinosarcoma: a case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2011 Apr 12. 9:39.[↩][↩]

- Hendaoui MS, Abed A, M’Saad W, et al. [A rare complication of renal lithiasis: peritonitis and splenic abscess caused by rupture of pyonephrosis]. J Urol (Paris). 1996. 102(3):130-3.[↩]

- [A case report of splenic abscesses due to pyonephrosis]. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2004 Apr;50(4):265-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15188621[↩]

- Mooreville M, Elkouss GC, Schuster A, et al. Spontaneous renocolic fistula secondary to calculous pyonephrosis. Urology. 1988 Feb. 31(2):147-50.[↩]

- Kim CJ, Kato K, Yoshiki T, et al. [Intractable duodenocutaneous fistula after nephrectomy for stone pyonephrosis: report of a case]. Hinyokika Kiyo. 2003 Sep. 49(9):547-50.[↩]

- Greenstein A, Kaver I, Chen J, et al. Does preoperative nephrostomy increase the incidence of wound infection after nephrectomy?. Urology. 1999 Jan. 53(1):50-2.[↩]

- Angulo JC, Gaspar MJ, Rodríguez N, García-Tello A, Torres G, Núñez C. The value of C-reactive protein determination in patients with renal colic to decide urgent urinary diversion. Urology. 2010 Aug. 76(2):301-6.[↩]

- Shaikh N, Borrell JL, Evron J, Leeflang MM. Procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, and erythrocyte sedimentation rate for the diagnosis of acute pyelonephritis in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Jan 20. 1:CD009185[↩]

- Lertdumrongluk K, Thongmee T, Kerr SJ, Theamboonlers A, Poovorawan Y, Rianthavorn P. Diagnostic accuracy of urine heparin binding protein for pediatric acute pyelonephritis. Eur J Pediatr. 2015 Jan. 174 (1):43-8.[↩]

- Demertzis J, Menias CO. State of the art: imaging of renal infections. Emerg Radiol. 2007 Apr. 14(1):13-22.[↩]

- van Nieuwkoop C, Hoppe BP, Bonten TN, Van’t Wout JW, Aarts NJ, Mertens BJ, et al. Predicting the need for radiologic imaging in adults with febrile urinary tract infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2010 Dec 1. 51(11):1266-72.[↩]

- Choi J, Jang J, Choi H, Kim H, Yoon J. Ultrasonographic features of pyonephrosis in dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 2010 Sep-Oct. 51(5):548-53.[↩]

- Stojadinovic M, Micic S, Milovanovic D. Ultrasonographic and computed tomography findings in renal suppurations: performance indicators and risks for diagnostic failure. Urol Int. 2008. 80(4):389-97.[↩]

- Wyatt SH, Urban BA, Fishman EK. Spiral CT of the kidneys: role in characterization of renal disease. Part I: Nonneoplastic disease. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1995. 36(1):1-37.[↩]

- Joudi FN, Kuehn DM, Williams RD. Maximizing clinical information obtained by CT. Urol Clin North Am. 2006 Aug. 33(3):287-300.[↩]

- Kim SH, Kim YW, Lee HJ. Serious acute pyelonephritis: a predictive score for evaluation of deterioration of treatment based on clinical and radiologic findings using CT. Acta Radiol. 2012 Mar 1. 53(2):233-8.[↩]

- Craig WD, Wagner BJ, Travis MD. Pyelonephritis: radiologic-pathologic review. Radiographics. 28 (1): 255-77. doi:10.1148/rg.281075171[↩]

- Tran MH, Sakow NK, Dorey JH. Detection of pyonephrosis using dual isotope imaging technique. Clin Nucl Med. 1994 Feb. 19(2):161-2.[↩]

- Ramsey S, Robertson A, Ablett MJ, Meddings RN, Hollins GW, Little B. Evidence-based drainage of infected hydronephrosis secondary to ureteric calculi. J Endourol. 2010 Feb. 24(2):185-9.[↩]

- Pearle MS, Pierce HL, Miller GL, et al. Optimal method of urgent decompression of the collecting system for obstruction and infection due to ureteral calculi. J Urol. 1998 Oct. 160(4):1260-4.[↩]

- Hemal AK, Mishra S. Retroperitoneoscopic nephrectomy for pyonephrotic nonfunctioning kidney. Urology. 2010 Mar. 75(3):585-8.[↩]