Reflux laryngitis

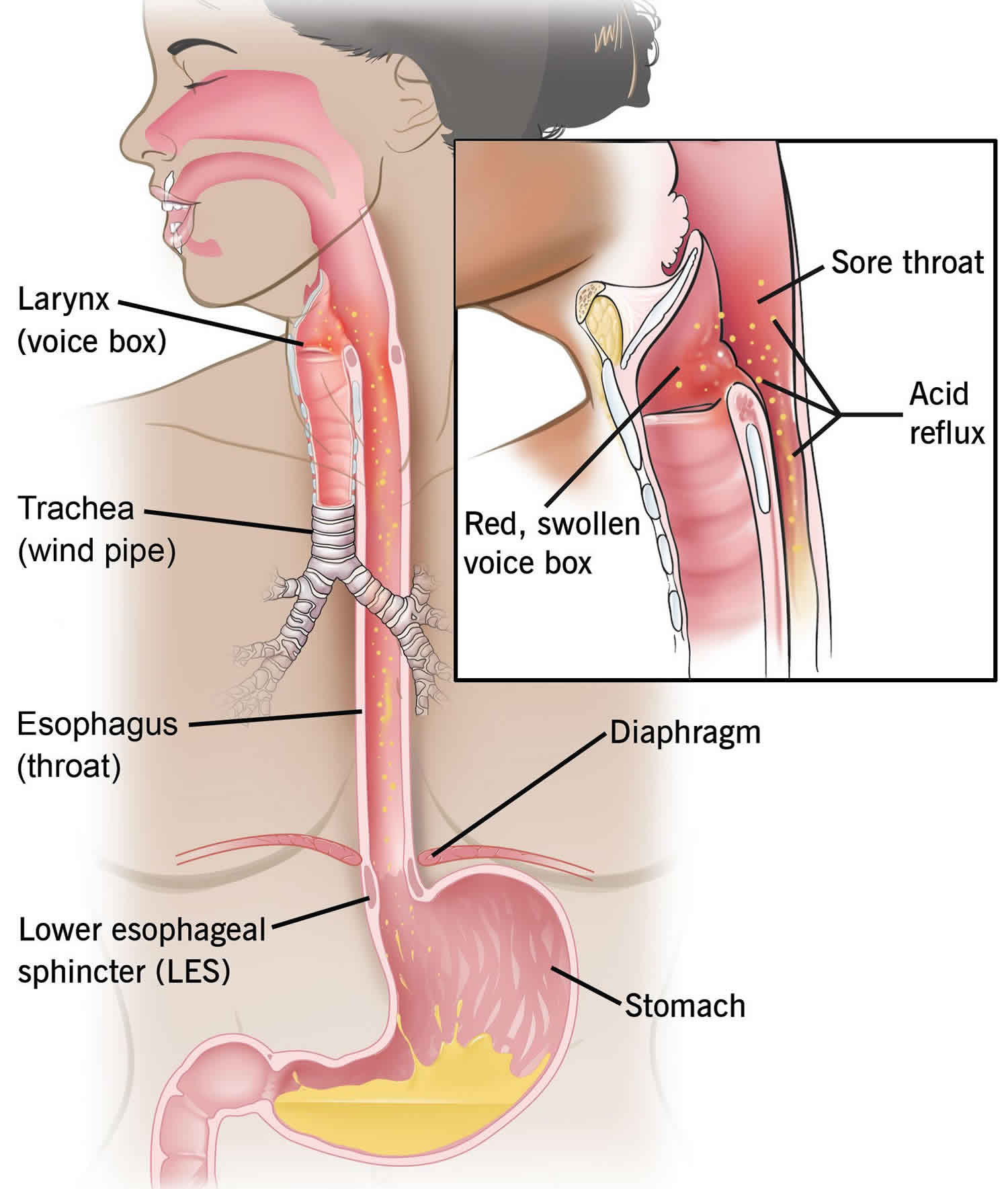

Reflux laryngitis is an inflammation of your voice box (larynx) from your stomach contents that come back up into your esophagus then into your larynx also called laryngopharyngeal reflux. Stomach acid that touches the lining of your esophagus can cause heartburn, also called gastroesophageal reflux, acid indigestion or heartburn. Inside the larynx are your vocal cords — two folds of mucous membrane covering muscle and cartilage. Normally, your vocal cords open and close smoothly, forming sounds through their movement and vibration. But with reflux laryngitis, your vocal cords become inflamed or irritated. This swelling causes distortion of the sounds produced by air passing over them. As a result, your voice sounds hoarse. In some cases of reflux laryngitis, your voice can become almost undetectable.

According to Sataloff, “laryngopharyngeal reflux incorporates a complex spectrum of abnormalities” 1. The airway is subdivided anatomically beginning with the oropharynx, then the hypopharynx, supraglottis, glottis, subglottis, and finally, the trachea. The area of concern, and what brings most patients into the clinic, is the effect of reflux on the glottis, or vocal cords. Reflux is normally sequestered within the stomach and sometimes escapes into the esophagus which has been described in other literature.

In healthy individuals, there are four barriers to reflux encroaching on the larynx. The lower esophageal sphincter, upper esophageal sphincter, esophageal peristalsis, and epithelial resistance factors with any dysfunction will lead to symptoms of laryngopharyngeal reflux.

The upper esophageal sphincter is the final gatekeeper in antireflux. The area of the distal pharynx and proximal esophageal only opens for specific physiologic demands, such as swallowing under tonic contraction. This is made up of the cricopharyngeus, thyropharyngeus, and the proximal cervical esophagus, forming a c-shaped sling that attaches to the cricoid cartilage. The tonic pressure induced by these muscles can be decreased with general anesthesia, sleep state, and cigarette consumption.

The lower esophageal sphincter is located at the gastroesophageal junction whose contracture leads to circular closure and prevention of egress of stomach acid. The diaphragmatic crura make up this critical antireflux mechanism.

The esophagus, with the help of gravity and peristalsis, can clear the acid that makes its way more proximal than expected. A mucus layer is present along the esophagus that is a barrier to large molecules, such as pepsin but does not help prevent acid penetration. Also present is the aqueous layer, which helps form an alkaline buffer.

Anyone can get laryngopharyngeal reflux, but it occurs more often as people age. People who are more likely to have laryngopharyngeal reflux include those who:

- Have certain dietary habits.

- Consistently wear tight or binding clothing.

- Are overweight.

- Are overstressed.

Reflux laryngitis causes

Most people will experience acid reflux and laryngitis if the lining of the esophagus and the larynx comes in contact with too much stomach juice. Stomach juice consists of acid, digestive enzymes, and other injurious materials. Ciliary flow is impeded at pH 5.0 and completely halted at pH 2.0. With decreased ciliary flow, there is a decrease in resistance to infection.

When you swallow, food passes down your throat and through your esophagus to your stomach. A muscle called the lower esophageal sphincter controls the opening between the esophagus and the stomach. The muscle remains tightly closed except when you swallow food.

When this muscle fails to close, the acid-containing contents of your stomach can travel back up into the esophagus and into the larynx. This backward movement is called reflux.

The retrograde flow of gastric acid and pepsin induces laryngeal mucosal damage and impaired mucociliary clearance. Three different theories explain this damage. Direct contact of acid and pepsin with the epithelium induces damage versus gastric refluxate with additional vocal abuse causes symptoms and mucosal lesions 2. The esophageal-bronchial reflex theory suggests that acid in the distal esophagus vagally stimulates a chronic cough induces laryngeal symptoms.

Reflux laryngitis prevention

To decrease your chance of having acid reflux laryngitis, avoid the following:

- Acidic, spicy and fatty foods

- Alcohol

- Tobacco

- Beverages that contain caffeine (tea, coffee, soda, etc.)

- Chocolate

- Mint or mint-flavored foods

Other things you can do to help prevent acid reflux laryngitis:

- Do not wear tight or binding clothing.

- Avoid becoming overly stressed. Learn ways to help manage or reduce stress levels.

- Be sure to maintain a healthy weight.

- Avoid eating less than 2 hours before bedtime.

Reflux laryngitis symptoms

Reflux laryngopharyngitis symptoms are felt in the throat and include the following 3:

- Sore throat

- Mild hoarseness

- Sensation of a lump in the throat

- The need to clear the throat

- The sensation of mucus sticking in the throat, and/or post-nasal drip

- Chronic (long-term) cough

- Difficulty swallowing

- Red, swollen, or irritated larynx (voice box).

Hoarseness was the most prevalent symptom in laryngopharyngeal reflux (100%) with none of the patients with the more common condition of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) reporting hoarseness 1. Patients with laryngopharyngeal reflux typically have upright, or daytime, reflux with good esophageal motor function 4. This is compared to supine, or nocturnal, patients with reflux who had esophageal motor dysfunction 5. Patients with gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) also often have dysfunction of their lower esophageal sphincter compared to upper esophageal sphincter pathology seen in laryngopharyngeal reflux 6.

If it is not treated, acid reflux laryngitis can lead to:

- Sore throat

- Chronic cough

- Swelling of the vocal folds

- Ulcers (open sores) on the vocal folds

- Formation of granulomas (masses) in the throat

- Worsening of asthma, emphysema, and bronchitis

Untreated acid reflux laryngitis also may play a role in the development of cancer of the voice box.

Reflux laryngitis diagnosis

Acid reflux laryngitis is usually diagnosed based on the patient’s symptoms of irritation or swelling in the throat and the back of the voice box. In many cases, no testing is needed to make the diagnosis.

If testing is needed, three commonly used tests are: a swallowing study; a direct look at the stomach and esophagus through an endoscope, and; an esophageal pH test. Detection of retrograde flow of stomach acid into the upper aerodigestive tract has been considered the gold standard. This is tested via a single probe or dual probe pH testing. Pathologic reflux is considered present when 0.1% of the study time has a pH of less than 4.0 7.

- In a swallowing study, the patient swallows a special liquid called barium, which coats the esophagus, stomach and intestine so they are outlined on an X-ray. This allows the doctor to see the movement of food as it passes from the mouth to the esophagus.

- The doctor can also view the inside of the stomach and esophagus with an endoscope, a long thin tube with a camera on the end that the doctor passes through the mouth, down the esophagus and into the stomach.

- The esophageal pH test measures and records the pH (level of acid) in the esophagus. A thin, small tube with a device on the tip that senses acid is gently passed through the nose, down the esophagus, and positioned about 2 inches above the lower esophageal sphincter. The tube is fastened to the side of the face with tape. The end of the tube that comes out of the nose is attached to a portable recorder that is worn on the belt or over the shoulder. The recorder has several buttons on it that the patient presses to mark certain events.

On physical exam, an otolaryngologist (ENT specialist) can perform laryngoscopy as well as videostroboscopy. Posterior thickening and pachyderma of laryngeal posterior commissure and post-cricoid mucosa have been associated with laryngopharyngeal reflux 8. Granulomas of the vocal process have also been highly associated 9. Videostroboscopy may show edema along the undersurface of the vocal fold from the anterior to the posterior commissure 10.

Reflux laryngitis treatment

Lifestyle modifications are the first step of management. This includes weight loss, small meal size, refraining from lying down within 3 hours of a meal, eating a low fat and low acid diet, avoiding carbonates or caffeinated beverages, stopping tobacco use, and reducing alcohol intake.

Lifestyle changes include the following:

- Follow a bland diet (low acid levels, low in fat, not spicy).

- Eat frequent, small meals.

- Lose weight.

- Avoid the use of alcohol, tobacco and caffeine.

- Do not eat food less than 2 hours before bedtime.

- Raise the head of your bed before sleeping. Place a strong, solid object (like a board) under the top portion of the mattress. This will help prop up your head and the upper portion of your body, which will help keep stomach acid from backing up into your throat.

- Avoid clearing your throat.

- Take over-the-counter medications, including antacids, such as Tums®, Maalox®, or Mylanta; stomach acid reducers, such as ranitidine (Tagamet® or Zantac®); or proton pump inhibitors, such as omeprazole (Prilosec®), pantoprazole (Protonix®), and esomeprazole (Nexium®). Be sure to take all medications as directed.

If these measures fail to achieve results, medications such as histamine-2 receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors can be used to suppress acid production. Surgical therapy such as Nissen fundoplication can also be advocated to decrease symptoms.

Reflux laryngitis prognosis

The prognosis for patients who have acid reflux laryngitis is good because most of the causes can be controlled with a healthy lifestyle. Long-term untreated reflux laryngitis will lead to chronic vocal abuse with resultant scarring of the true vocal folds. Laryngopharyngeal reflux may also be related to untreated GERD, which can lead to Barrett esophagitis if left untreated. Also, one study showed in a retrospective chart review that untreated laryngopharyngeal reflux can lead to subglottic stenosis over time 11.

- Sataloff RT. Gastroesophageal reflux-related chronic laryngitis. Commentary. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2010 Sep;136(9):914-5.[↩][↩]

- Johnston N, Wells CW, Samuels TL, Blumin JH. Rationale for targeting pepsin in the treatment of reflux disease. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2010 Aug;119(8):547-58.[↩]

- Burton LK, Murray JA, Thompson DM. Ear, nose, and throat manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux disease. Complaints can be telltale signs. Postgrad Med. 2005 Feb;117(2):39-45.[↩]

- Postma GN, Tomek MS, Belafsky PC, Koufman JA. Esophageal motor function in laryngopharyngeal reflux is superior to that in classic gastroesophageal reflux disease. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2001 Dec;110(12):1114-6.[↩]

- Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms improve before changes in physical findings. Laryngoscope. 2001 Jun;111(6):979-81.[↩]

- Sivarao DV, Goyal RK. Functional anatomy and physiology of the upper esophageal sphincter. Am. J. Med. 2000 Mar 06;108 Suppl 4a:27S-37S.[↩]

- Smit CF, Tan J, Devriese PP, Mathus-Vliegen LM, Brandsen M, Schouwenburg PF. Ambulatory pH measurements at the upper esophageal sphincter. Laryngoscope. 1998 Feb;108(2):299-302.[↩]

- Ylitalo R, Lindestad PA, Ramel S. Symptoms, laryngeal findings, and 24-hour pH monitoring in patients with suspected gastroesophago-pharyngeal reflux. Laryngoscope. 2001 Oct;111(10):1735-41.[↩]

- Noordzij JP, Khidr A, Desper E, Meek RB, Reibel JF, Levine PA. Correlation of pH probe-measured laryngopharyngeal reflux with symptoms and signs of reflux laryngitis. Laryngoscope. 2002 Dec;112(12):2192-5.[↩]

- Belafsky PC, Postma GN, Koufman JA. Laryngopharyngeal reflux symptoms improve before changes in physical findings. Laryngoscope. 2001 Jun;111(6):979-81[↩]

- Maronian NC, Azadeh H, Waugh P, Hillel A. Association of laryngopharyngeal reflux disease and subglottic stenosis. Ann. Otol. Rhinol. Laryngol. 2001 Jul;110(7 Pt 1):606-12.[↩]