Saddle nose

Saddle nose or saddle nose deformity, is a loss of height in the bridge of the nose is always associated to cartilaginous or bone defects 1. Saddle nose deformity could have congenital, traumatic, infectious or iatrogenic origin. Its correction consists not only in a camouflage, but also it is important to reconstruct the missing structure.

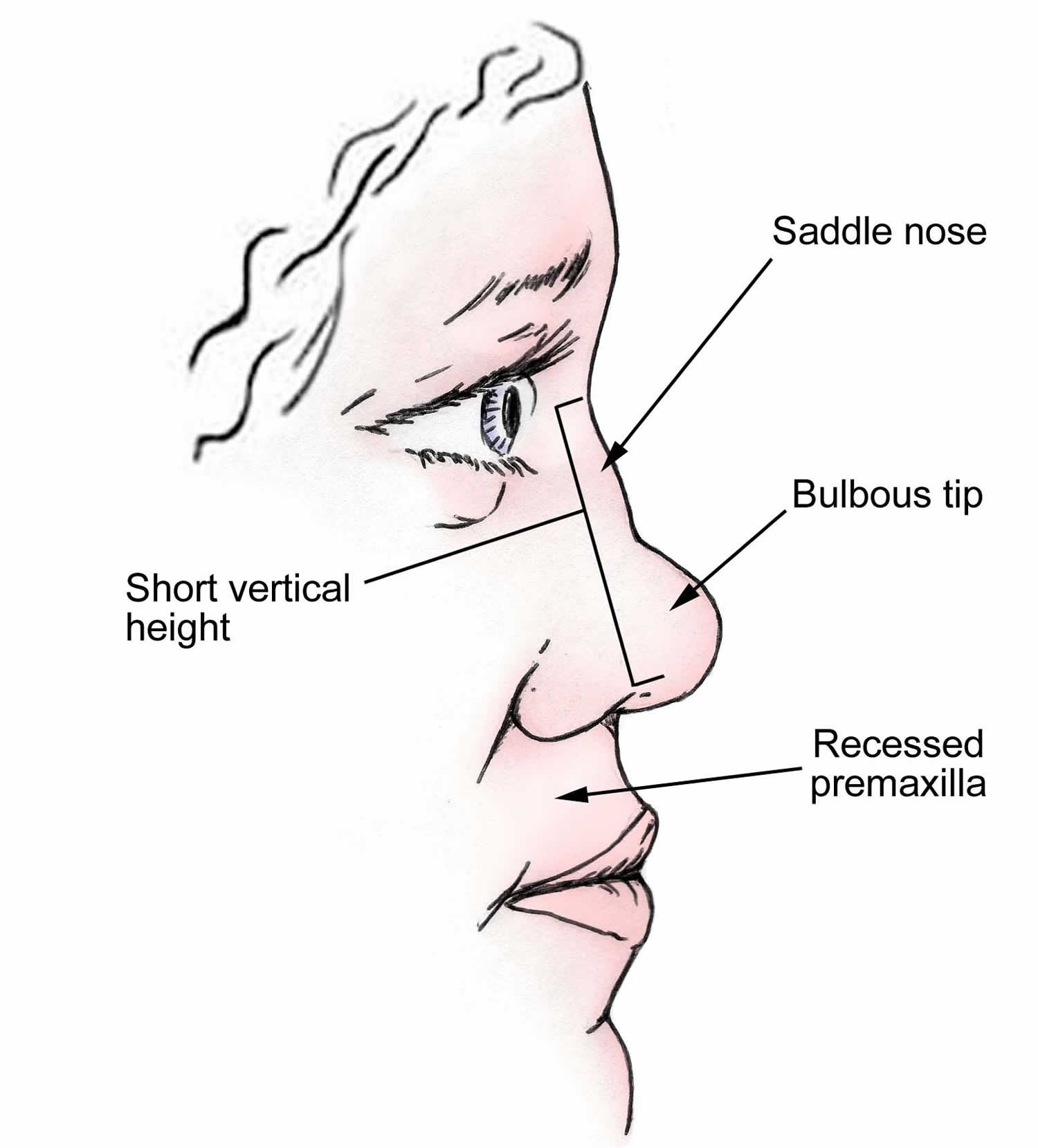

Figure 1. Saddle nose

Footnote: Findings typical of a moderate-to-severe saddle nose include nasal dorsal concavity, shortened vertical nasal length, and loss of nasal tip support and projection.

Saddle nose deformity classification

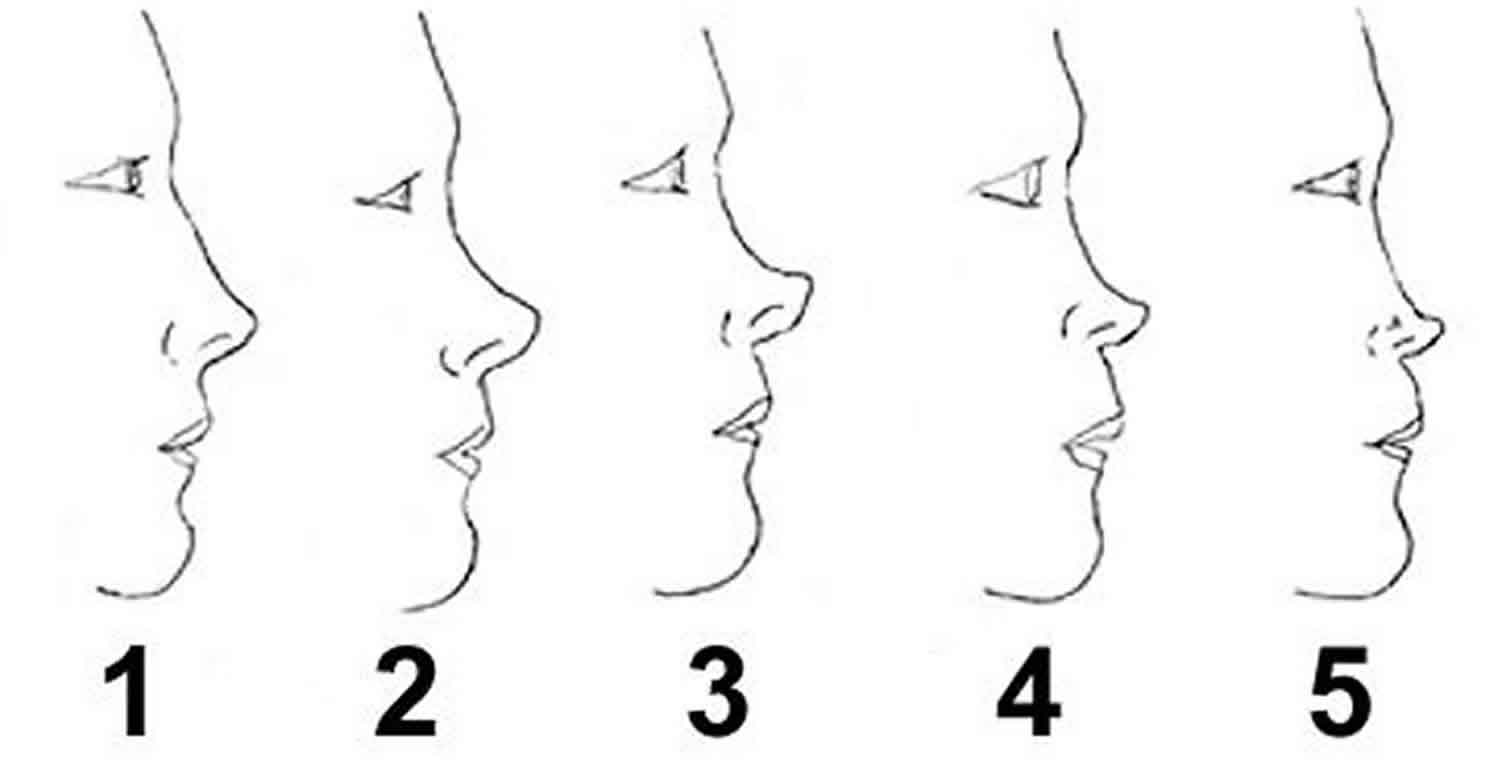

Categorizing the severity of the saddle nose is helpful. The authors use a simplified system that classifies saddle-nose deformities on the basis of the anatomic deficits (see Figure 2 below), as follows 2:

- Type 1 – Minor supratip or nasal dorsal depression, with a normal projection of lower third of the nose

- Type 2 – Depressed nasal dorsum (moderate to severe) with relatively prominent lower third

- Type 3 – Depressed nasal dorsum (moderate to severe) with loss of tip support and structural deficits in the lower third of the nose

- Type 4 – Catastrophic (severe) nasal dorsal loss with significant loss of the nasal structures in the lower and upper thirds of the nose

Most patients with a type 2, 3, or 4 saddle-nose deformity have functional nasal airway obstruction.

A practical classification method described by Tardy divides saddle-nose deformities into 3 categories, as follows:

- Minimal – Supratip depression greater than the ideal 1-2 mm tip-supratip differential

- Moderate – Moderate degrees of saddling due to loss of dorsal height of the quadrangular cartilage, usually with septal damage

- Major – More severe degree of saddling with major cartilage loss and major stigmata of a saddle-nose deformity

Figure 2. Saddle-nose classification

Footnote: Saddle-nose classification based on anatomic deficits. (1) Normal nose, appropriate nasal dorsal height, tip projection, and vertical nasal height. (2) Type 1 saddle-nose deformity, minor supratip or nasal dorsal depression, with normal projection of lower third of the nose. (3) Type 2 saddle-nose deformity, depressed nasal dorsum (moderate to severe) with relatively prominent lower third. (4) Type 3 saddle-nose deformity, depressed nasal dorsum (moderate to severe) with loss of tip support and structural deficits of the lower third of the nose. (5) Type 4 saddle-nose deformity, catastrophic (severe) nasal dorsal loss with significant loss of the nasal structures in the lower and upper thirds of the nose.

Saddle nose causes

Saddle nose deformity causes may include:

- Cleidocranial dysostosis

- Congenital syphilis

- Down syndrome

- Normal variation

- Other syndromes that are present at birth (congenital)

- Williams syndrome

A saddle-nose deformity can be congenital or acquired. Various degrees of nasal dorsal depression can be noticed as a part of individual, familial, syndromic, and racial characteristics. Most saddle-nose deformities are acquired. A common theme in all acquired saddle-nose deformities is a structural compromise of the nasoseptal cartilage leading to decreased dorsal nasal structural support. The most common causes of saddle-nose deformities are traumatic and iatrogenic.

Trauma

Direct trauma to the nose can fracture the cartilaginous and/or bony septum, hence compromising important support structures 3. Nasal bone depression due to trauma can also lead to a depressed dorsum. An unrecognized posttraumatic septal hematoma may become infected, causing irreversible cartilage damage and loss of support. In a study by Jalaludin 4, saddling was noted in 14% of patients with unrecognized or untreated septal abscesses. In that study, the leading cause of a nasal septal abscess was trauma. Birth-related nasoseptal trauma can also appear with various degrees of nasal deformity that may be erroneously labeled as being congenital.

Surgical causes

Changes made to the nose after rhinoplasty or submucous resection of septal cartilage can result in a number of undesirable deformities, including a saddle-nose deformity. Tzadik and colleagues 5 noted that, depending on the surgeon’s skill, saddling rates varied from 0% to 2.6% (average, 0.4%) in patients who had undergone submucous resection of the nasal septum.

Overresection of septal cartilage can lead to collapse of the middle vault and saddling. Removing too much septal cartilage can compromise the structural integrity of the dorsal L-shaped strut and increase the probability of postoperative or traumatic saddling of the nasal dorsum. No cartilage should be resected anterior to an imaginary vertical line drawn from the rhinion (osseocartilaginous junction) to the nasal spine. During septal cartilage resection, leaving a minimum of a 10-mm dorsal-caudal L-shaped margin of cartilage is important. Arching the incisions, instead of creating right-angled corners, can also impart slightly greater structural integrity to the dorsal L-shaped strut.

Surgical overreduction of a nasal dorsal hump can produce an overly concave nasal dorsum. Additionally, an unidentified open roof deformity can further contribute to middle vault depression. Disharmonious changes in the nasal contour (eg, an overly projected nasal tip, an exaggerated supratip break) can also impart the impression of saddling. Inadequate support of the upper lateral cartilages and the middle vault may lead to its settling and relative saddling of the middle vault with time.

Medical causes

A number of medical conditions affecting the nose can result in damage to the septum and cartilaginous structures. The common pathway is damage to the cartilage; compromise in the structure; and various degrees of subsequent nasal dorsal saddling, as clinically observed. A number of conditions can affect the nasal septum and lead to a saddle-nose deformity.

- Wegener granulomatosis

- Relapsing polychondritis

- Leprosy (Hansen disease)

- Syphilis

- Ectodermal dysplasia

Intranasal cocaine use leading to large septal perforation and cartilage loss can also produce saddling of the nose.

Wegener granulomatosis is characterized by necrotizing granulomas and vasculitis of the upper and lower respiratory tracts, including the nasal septum. The cycle of necrotizing granulomatous lesion and microabscess formation leads to cartilage destruction.

In relapsing polychondritis (see the images below), recurrent episodes of autoimmune cartilage inflammation and destruction result in damage to the cartilaginous structure of the ears, nose, larynx, trachea, and peripheral joints. In this rare disease, fibrotic tissue replaces collagen, elastin, and other matrix proteins found in normal cartilage; this process leads to the loss of healthy cartilage 6.

Overall, Hansen disease, or leprosy, is rare in the United States. However, it may be more common in the Gulf states (Texas and Louisiana), and it is endemic in certain areas of the world. The nasal mucosa is frequently involved, and septal ulceration and perforations are common. Nasal deformities, including saddling, are common in advanced cases.

Syphilis can cause intranasal ulcerative lesions that can lead to osteochondritis; cartilage damage; and, eventually, saddle-nose deformity.

Saddle nose symptoms

Patients with saddle-nose deformities may have various degrees of nasal obstruction. Middle vault collapse is commonly observed in moderate-to-severe saddle noses. The inferomedial collapse of the upper lateral cartilages and corresponding narrowing of the internal nasal valve can produce significant obstruction that impairs nasal breathing. Large septal perforations often result in nasal saddling. Saddle-nose deformities with septal perforations can appear with nasal crusting, nasal obstruction, and whistling upon nasal airflow. In individuals in whom nasal airway compromise is noted, nasoseptal reconstruction should address important functional, as well as aesthetic, deficits of the patient’s nose. An exact understanding of the deformity and dysfunction can allow for the proper selection of the best reconstructive option.

Saddle nose diagnosis

Complete history taking and physical examination is an important first step in evaluating the patient with a saddle-nose deformity. In particular, the history should include an investigation of the suspected etiology of the deformity, any history of nasal airway obstruction, any history of antecedent nasal trauma, the number of previous nasal surgeries, and any history of any autoimmune diseases. The use of intranasal cocaine or heroin should be investigated in patients with nasoseptal perforations.

Upon physical examination, the degree and location of saddling, the state of the nasal septum, the status of the internal and external nasal valves, and the structural integrity of the nasal support structures must be evaluated. A higher rate of septal perforations is found in patients who have a saddle noses. Endoscopic nasal examination can facilitate an accurate survey of all endonasal structures. The standard series of photographs should be obtained prior to surgical planning for rhinoplasty.

Imaging studies

- The standard series of photographs should be obtained prior to surgical planning for rhinoplasty.

- Radiologic work-up is not necessary, unless required for medicolegal or insurance documentation.

Diagnostic procedures

- Endoscopic nasal examination can facilitate an accurate survey of the endonasal structures.

Saddle nose treatment

Medical treatment applies only to limiting the progression of those disease states that lead to cartilage destruction and eventual saddling. Diseases such as Wegener granulomatosis and relapsing polychondritis should be managed with the help of medical specialists (rheumatologists). In most individuals with saddle-nose deformities, treatment is aimed at surgical reconstruction of functional and aesthetic deficits.

Saddle nose surgery

Indications for nasal reconstruction must be tempered by patient selection, the surgeon’s experience, and the etiology of the deformity. Indications for surgery can be functional, aesthetic, or, most commonly, both. Examples are as follows:

- Nasal airway obstruction secondary to middle vault collapse and/or incompetency of the internal or external nasal valve in a patient with a saddle-nose deformity

- Nasal airway obstruction secondary to perforation of the loss of septal cartilage in the patient with a saddle-nose deformity

- The patient’s desire for aesthetic improvement.

Saddle nose is one of the most difficult morpho-functional deformities of the nose to correct, as it entails not only masking with a graft but also planned anatomical reconstruction of all the structures involved. Grafts obtained from septal or conchal cartilage, sutured in overlapping layers so as to increase the thickness where necessary, can be sufficient in cases of low to medium severity. The presence of septal remnants can be exploited to combine septal grafts with grafts of auricular concha in order to increase the thickness of the final graft. There is instead less agreement on the choice of material for use in reconstruction in cases of greater severity, where the absence of cartilage is often combined with the absence of the bony support of the nasal pyramid. The ideal graft material must be nontoxic, non-carcinogenic, non-allergenic, nondestructive with respect to adjacent tissues, non-resorbable, readily available, and sterilizable as well as easy to shape and to remove if necessary.

The variety of autogenous (bony and cartilaginous), homologous (irradiated cartilage), and alloplastic grafts put forward in the literature attests to the nonexistence of one “ideal” material. Alloplastic grafts have a tendency toward extrusion and infection, and homologous grafts are characterized by the highest rate of resorption. The bone is difficult to shape, requires solid stabilization, and can be reabsorbed. In the end, despite its tendency toward distortion, costal cartilage remains at present the material of choice for the correction of severe cases of saddle nose.

The future of nasoseptal reconstruction continues to evolve on the basis of long-term results, the introduction of new techniques, and the use of increasingly biocompatible homografts and implants 7. The ideal alloplasts are yet to be found, but the search for new compounds may facilitate the development of an ideal alloplast. Future developments in bioengineering may allow the production of autologous soft tissue products (eg, cartilage). This advancement will eliminate the importance of material as a limiting factor in complicated nasal reconstructions. Until then, the intelligent and creative use of autogenous grafts can allow the surgeon to address an almost limitless array of nasal deformities, including the saddle nose.

Saddle nose surgery contraindications

Persons with contraindications for repairing a saddle-nose deformity include the following:

- Patients with malignant, chronic, or autoimmune disease conditions (eg, relapsing polychondritis) in whom the reconstructed nose is at risk for continuing damage

- Persons who abuse drugs intranasally and who have not demonstrated at least 12 months of sobriety (Nasal reconstruction is contraindicated in patients who have not definitively demonstrated complete rehabilitation from their substance abuse.)

- Patients who are poor candidates for rhinoplasty in general, including unhealthy patients with poor perioperative risk profile and patients whose ability to follow the postoperative care regimen is limited (ie, patients with severe schizophrenia)

- Patients with unrealistic expectations

Patients with relative contraindications include the following:

- The patient with multiple previous rhinoplasties who now has scarred-down thin skin. The history of smoking or an unrealistic expectation by such a patient can also serve as reason[s] to delay or dissuade the patient from surgery.

- Aesthetic rhinoplasty in patients younger than 16 years

- Patients who are expected by habit or profession (mixed martial artists, boxers) to experience repeated nasal trauma

Saddle nose surgery techniques

Depending on the degree of saddling, different reconstructive options can be used. Decisions regarding nasal reconstruction are concerned both with the choice of materials to be used and the type of reconstruction needed.

The history of nasal reconstruction is full of nasal implants and grafts taken from a variety of sources. The interesting list of grafts and implants used in reconstructing the nose seems almost limitless. Some historic grafts and implants used in the human nose include the following:

- Autografts – Auricular cartilage, rib, patient’s finger 8

- Homografts – Irradiated rib, pooled acellular dermis

- Xenografts – Leather, duck’s sternum, bovine cartilage

- Precious metals – Titanium, gold, silver, metal alloys

- Inert bioimplants – Coral, ivory

- Synthetic compounds – Silicone, polytetrafluoroethylenes, polyamide mesh

Variable rates of success and failure have been noted with different implants and grafts. The selection of material in nasal reconstruction should center on balancing long-term biocompatibility, infection rates, extrusion rates, graft resorption rates, graft harvest site morbidity, and material availability. The ideal implant’s profile satisfies all of these concerns. The ideal nasal implant has yet to be developed.

The ideal nasal implant should have certain characteristics, as follows:

- It is noncarcinogenic.

- It is nonimmunogenic (no foreign body or inflammatory reaction).

- It is nonresorbable.

- It is easy to work with and malleable.

- It has a tactile feel similar to that of tissue (cartilage).

- It has a low or zero extrusion rate.

- It allows biointegration of the implant with the surrounding tissue.

- It is cost effective.

In a systematic review involving patients with Wegener granulomatosis–related saddle nose deformity, Ezzat et al 9 reported that the deformity can be safely and effectively corrected with rhinoplasty. The surgery (primary and secondary) was successful in 37 out of 44 study patients (84.1%), with the complication rate found to be 20%. The procedure was most effective when a single L-shaped strut graft composed of autologous tissue was used, as opposed to individually placed grafts 9.

Another systematic review, by Coordes et al 10, also found rhinoplasty to be safe in Wegener granulomatosis patients with saddle nose deformity (with all members of the study group having minimal or no local disease at the time of their procedure). However, the investigators found that the likelihood of revision surgery was greater in individuals with Wegener granulomatosis than in rhinoplasty patients without the disease 10.

Autogenous materials

Autogenous materials are always preferred to alloplastic implants as far as infection rates, extrusion rates, and biocompatibility issues are concerned. Septal cartilage is the best choice but is often not present in sufficient quantity. Secondary sources of autogenous cartilage include auricular and rib cartilage. Cartilage harvested from the ear is especially well suited for use in the nose. Bone grafts harvested from calvarial, iliac, and tibial bone sources can be used. Autogenous soft tissue materials include dermis and fascia.

Homografts

Homografts are harvested from healthy screened donors. Irradiated cartilage and sheets of pooled acellular dermal allografts (AlloDerm; LifeCell Corp, Houston, Texas) are the homografts most commonly used in nasal dorsal reconstruction.

Alloplasts

Synthetic implants offer the advantages of ready availability. However, in the nose, alloplasts have a tendency to behave like foreign bodies, with higher rates of infection, extrusion, and inflammatory reactions, as compared with those of autogenous grafts. Moreover, although alloplasts are well suited as filler material, most do not provide significant structural support to the nose.

Commonly available alloplasts include polyamide mesh (Mersilene; Ethicon, Sommerville, New Jersey), silicone-based implants (Silastic; Dow Corning, Midland, Michigan), expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) (Gore-Tex; WL Gore and Associates, Flagstaff, Arizona), and porous high-density polyethylene (PHDPE) (Medpor; Porex Surgical, Newnan, Georgia) 11.

Proponents of alloplasts note that autogenous cartilage grafts are fraught with problems that must be considered. As mentioned before, septal cartilage is often of low quantity or nonexistent. Auricular cartilage is available; however, it is curved, it can potentially warp with time, it is of limited quantity, and it involves the morbidity of a second operative site. Rib cartilage is susceptible to warping and involves the morbidity of a second operative site. Also, some surgeons may be uncomfortable with the possible risks related to the thoracic surgical site. Bone grafts have been reported to undergo resorption. They are hard and can also result in donor-site morbidities.

At times, because of a number of factors, including strong patient preference against a second operative site, alloplastic implants may be used. ePTFE has been in use for a number of years, and positive reports have encouraged their wider use. Outcomes pertaining to synthetic implants are discussed in the Outcome and Prognosis section.

Porous high-density polyethylene (PHDPE) implants have pore sizes of 125-250 µm, which allow access to immune cells and fibrovascular ingrowth. Sclafani, Thomas, and colleagues (1997) demonstrated the ingrowth of fibrovascular tissue into these porous implants, which confers increased resistance toward implant infection 12. This ingrowth also anchors the implant to the surrounding native tissue.

Despite several promising reports, the long-term viability of these implants has yet to be evaluated. Alloplasts must be recommended only as a last resort and not as a convenient substitute for autogenous grafts. One significant disadvantage of nasal implants includes the changes to the surrounding tissue (scarring, skin atrophy), which may render less-than-optimal results in subsequent rhinoplasties. The authors’ hesitancy to use any foreign materials in the nose is based on the authors’ and other colleagues’ experience with the removal of displaced, infected, or extruding nasal implants placed by other surgeons.

Saddle nose surgery complications

Complications encountered after saddle-nose reconstruction can be categorized as medical, functional, or aesthetic. Complications vary with the amount and duration of surgery, the surgical approach to the nose, the amount of dissection, the number of previous surgeries, the use and choice of reconstruction materials, and the intrinsic patient factors.

- Medical complications

- Infection – Localized cellulitis, abscess formation, infected implant, or infected graft harvest site

- Perioperative medical events – Atelectasis or pneumothorax with rib cartilage harvest

- Anesthesia related – Intubation-related injuries

- Functional complications – Nasal obstruction due to inferior migration of spreader grafts, restenosis of the internal nasal valve, iatrogenic septal perforation, or synechia

- Aesthetic complications

- Graft related – Migration or displacement, warping, visibility of graft through thin skin or with time, or resorption of graft

- Alloplast implant related – Extrusion, displacement, or unnatural implant contours

- Transcolumellar incision related – Prolonged localized erythema, stitch granuloma, scarring (rare), or nasal tip ischemia (very rare)

- General rhinoplasty related – Loss tip definition or symmetry, polly beak deformity or loss of favorable supratip break, inappropriate columellar show, alar-columellar disproportion, crooked nose deformity, or other well-recognized rhinoplasty complications

Saddle nose surgery prognosis

Long-term outcomes at 10 years or longer are the standards by which rhinoplasty and nasoseptal reconstruction procedures should be judged and evaluated. Most available studies are limited by short follow-up, small numbers of patients, outcomes influenced by the surgeon’s experience with a particular approach or technique, variability in intrinsic patient factors, and patient selection. Nevertheless, reviewing the available, albeit imperfect, data on the use alloplasts and the application of autogenous grafts is useful.

Alloplasts

The infection and extrusion rates of synthetic implants are of prime concern regarding their wider nonselective use in rhinoplasty. Most published studies reveal alloplast infection rates of 2-4%. True implant extrusion rates are difficult to ascertain because of variable patient follow-up intervals, patients lost to follow-up, and the lack of substantial long-term studies. On the basis of available studies, implant extrusion rates range from 0% to 9%.

Conrad and Gillman evaluated 13 the use of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (ePTFE) implants in 189 patients undergoing rhinoplasty. Follow-up intervals varied from 3 months to 6 years (average, 17.5 months) with 5 cases (2.6%) of implant removal secondary to infection. Two implants were removed because of chronic inflammation and soft tissue reaction. No cases of implant extrusion, migration, or resorption were reported.

Godin et al 14 reviewed 309 patients who received ePTFE implants for a 10-year period. With an average follow-up of 40.4 months (range, 5 mo-10 y), 10 implants (3.2%) were removed secondary to infection.

Niechajev’s 15 review of 23 nasal reconstructions using porous high-density polyethylene (PHDPE) nasal implants revealed successful aesthetic outcomes in all patients, with a mean follow-up of 2 years (range, 1-3 years). In this study, 2 implant extrusions (9%) were treated with minor revision surgery, and 1 case of implant infection (4%) was treated with antibiotics.

Turegun et al 16 used PHDPE implants in reconstructing the noses of 36 individuals with saddle-nose deformities and reported that no cases required implant removal. However, the follow-up in this study was generally short (8-18 months), and the aesthetic and functional outcomes were poorly defined.

Romo et al 17 used PHDPE nasal implants in 15 saddle-nose reconstructions and noted 1 major complication because of a twisted dorsal implant at 1-year follow-up. Of the 15 patients, 14 (93%) were pleased with their aesthetic outcomes (follow-up duration unknown). Despite attempts at precise contouring of the implant prior to its placement, the investigators noted demarcation of the lateral borders of a number of implants placed on the dorsum.

In another study, Romo et al 17 applied PHDPE implants in 121 cases involving revision rhinoplasty and in 66 platyrrhine noses. In most cases, the implant was used to augment the dorsum and reinforce the columella. From a total of 187 cases, 5 implants (2.7%) needed to be removed because of 3 early and 2 delayed implant infections.

Beekhuis’ report 18 of 70 patients with various degrees of nasal dorsal saddling who were all treated with rhinoplasty and polyamide mesh placement revealed 3 cases (4%) of implant removal (all because of infection).

Autogenous material

In a review article about surgical correction of the saddle-nose deformity, Tardy 19 describes his 20-year experience in using various autogenous grafts in nasal reconstruction with gratifying results and no major complications. Infection rates with autogenous cartilage are low, and infections can be successfully treated with antibiotics. Rates of auricular cartilage warping are variable but approximately 4-7%. Cartilage extrusion rates are less than 5%, with most cases of extrusion resolving spontaneously.

Sherris treated 21 patients requiring caudal and dorsal septal reconstruction by using only autogenous material. Material used included septal cartilage; autogenous rib grafts; ethmoid bone; and, in one case, calvarial bone grafts. With an average follow-up of 19.8 months (range, 12-29 mo), no cases of infection, graft extrusion, or warping were noted. He noted one case (5%) of partial (rib) graft exposure, which resolved spontaneously without any sequelae, and one case (5%) in which (calvarial bone) graft resorption in the nasal tip area had been noted at 2-year follow-up. Aesthetic outcomes were “much improved” in 76% of the cases and “improved” in the remaining 24%.

Murakami et al 20 used irradiated rib cartilage to reconstruct 18 saddle-nose deformities. With a follow-up of 1-6 years (mean, 2.8 y), no cases of infection, extrusion, or noticeable resorption were noted. One (6%) graft had to be removed secondary to warping, and 2 (11%) displaced caudal struts had to be repositioned under local anesthesia. Long-term evaluation of irradiated cartilage grafts by Welling et al revealed progressive graft resorption with time 21. Animal studies by Donald 22 have also demonstrated the steady resorption of irradiated cartilage with time. This resorption may discourage the use of irradiated cartilage in younger patients, in whom long-term resorption may limit the lifespan of the nasal reconstruction.

Adams et al 23 have demonstrated decreased rib cartilage warping rates when the cartilages were carved from central portion rather than peripheral portions of the harvested cartilage. Gunter and colleagues significantly reduced their postoperative cartilage warping rates by internally stabilizing rib cartilage grafts by using Kirschner wires (K-wires) 24. Toriumi 25 describes minimizing the risk of long-term warping by performing adequate symmetric carving of the graft, by not leaving any perichondrium on the graft, and by dissecting a precise subperiosteal graft insertion pocket.

Ozturan et al 26 described the use of an “accordion” technique for preventing costal cartilage warping in saddle-nose repair. In the surgery, on 23 patients with severe saddle-nose deformity, a horizontal transection was made every 2 mm along the length of the costal cartilage graft (on alternate sides) prior to graft implantation. None of the patients experienced postoperative warping. In contrast, seven of 18 patients (39%) with comparable saddle-nose deformity who underwent costal cartilage repair without use of the accordion technique suffered early and/or late postoperative warping 26.

In the study by Gerow et al 27, the use of rib bone grafts for 16 saddle-nose reconstructions yielded good aesthetic results with no significant complications. Some of the cases described had continued good aesthetic results at long-term follow-up (7-10 years). Bone absorption was noted in all cases, but in no cases did the deformities recur.

- Saddle Nose: A Systematic Approach. https://www.intechopen.com/books/contemporary-rhinoplasty/saddle-nose-a-systematic-approach[↩]

- Saddle Nose Rhinoplasty. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/840910-overview#a9[↩]

- Won TB, Kang JG, Jin HR. Management of post-traumatic combined deviated and saddle nose deformity. Acta Otolaryngol. 2012 Jun. 132 Suppl 1:S44-51.[↩]

- Jalaludin MA. Nasal septal abscess–retrospective analysis of 14 cases from University Hospital, Kuala Lumpur. Singapore Med J. 1993 Oct. 34(5):435-7.[↩]

- Tzadik A, Gilbert SE, Sade J. Complications of submucous resections of the nasal septum. Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 1988. 245(2):74-6.[↩]

- Chauhan K, Hanna A. Relapsing Polychondritis. [Updated 2020 Jan 24]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK436007[↩]

- Hong SN, Mutsumay S, Jin HR. Long-term Results of Combined Rhinoplasty and Septal Perforation Repair. JAMA Facial Plast Surg. 2016 Dec 1. 18 (6):475-80.[↩]

- Young K, Rowe-Jones J. Current approaches to septal saddle nose reconstruction using autografts. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011 Aug. 19(4):276-82.[↩]

- Ezzat WH, Compton RA, Basa KC, Levi J. Reconstructive Techniques for the Saddle Nose Deformity in Granulomatosis With Polyangiitis: A Systematic Review. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2017 May 1. 143 (5):507-12.[↩][↩]

- Coordes A, Loose SM, Hofmann VM, et al. Saddle nose deformity and septal perforation in granulomatosis with polyangiitis. Clin Otolaryngol. 2018 Feb. 43 (1):291-9.[↩][↩]

- Razmpa E, Saedi B, Mahbobi F. Augmentation rhinoplasty with combined use of Medpor graft and irradiated homograft rib cartilage in saddle nose deformity. Arch Iran Med. 2012 Apr. 15(4):235-8.[↩]

- Sclafani AP, Thomas JR, Cox AJ, Cooper MH. Clinical and histologic response of subcutaneous expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex) and porous high-density polyethylene (Medpor) implants to acute and early infection. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997 Mar. 123(3):328-36.[↩]

- Conrad K, Gillman G. A 6-year experience with the use of expanded polytetrafluoroethylene in rhinoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998 May. 101(6):1675-83; discussion 1684.[↩]

- Godin MS, Waldman SR, Johnson CM Jr. Nasal augmentation using Gore-Tex. A 10-year experience. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 1999 Apr-Jun. 1(2):118-21; discussion 122.[↩]

- Niechajev I. Porous polyethylene implants for nasal reconstruction: clinical and histologic studies. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1999 Nov-Dec. 23(6):395-402.[↩]

- Turegun M, Sengezer M, Güler M. Reconstruction of saddle nose deformities using porous polyethylene implant. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1998 Jan-Feb. 22(1):38-41.[↩]

- Romo T 3rd, Sclafani AP, Sabini P. Use of porous high-density polyethylene in revision rhinoplasty and in the platyrrhine nose. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 1998 May-Jun. 22(3):211-21.[↩][↩]

- Beekhuis GJ. Surgical correction of saddle nose deformity. Trans Sect Otolaryngol Am Acad Ophthalmol Otolaryngol. 1975 Nov-Dec. 80(6):596-607.[↩]

- Tardy ME Jr, Schwartz M, Parras G. Saddle nose deformity: autogenous graft repair. Facial Plast Surg. 1989 Winter. 6(2):121-34.[↩]

- Murakami CS, Cook TA, Guida RA. Nasal reconstruction with articulated irradiated rib cartilage. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991 Mar. 117(3):327-30; discussion 331.[↩]

- Welling DB, Maves MD, Schuller DE, et al. Irradiated homologous cartilage grafts. Long-term results. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1988 Mar. 114(3):291-5.[↩]

- Donald PJ. Cartilage grafting in facial reconstruction with special consideration of irradiated grafts. Laryngoscope. 1986 Jul. 96(7):786-807.[↩]

- Adams WP Jr, Rohrich RJ, Gunter JP, et al. The rate of warping in irradiated and nonirradiated homograft rib cartilage: a controlled comparison and clinical implications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1999 Jan. 103(1):265-70.[↩]

- Gunter JP, Clark CP, Friedman RM. Internal stabilization of autogenous rib cartilage grafts in rhinoplasty: a barrier to cartilage warping. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1997 Jul. 100(1):161-9.[↩]

- Toriumi DM. Autogenous grafts are worth the extra time. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000 Apr. 126(4):562-4.[↩]

- Ozturan O, Aksoy F, Veyseller B, et al. Severe saddle nose: choices for augmentation and application of accordion technique against warping. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2013 Feb. 37(1):106-16.[↩][↩]

- Gerow FJ, Stal S, Spira M. The totem pole rib graft reconstruction of the nose. Ann Plast Surg. 1983 Oct. 11(4):273-81.[↩]