Sleep apnea

Sleep apnea also called sleep apnoea or sleep apnea syndrome is a sleep-related breathing disorder in which your breathing completely stops (apnea) or get very shallow episodically during sleep 1, 2, 3. These episodes usually last 10 seconds or more and occur repeatedly throughout the night. Apnea refers to a pause in your breathing for more than 10 seconds 4, 5. Breathing pauses can last from a few seconds to minutes. Breathing pauses may occur 30 times or more an hour. There are 2 types of sleep apnea: central sleep apnea (CSA) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Central sleep apnea (CSA) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are differentiated by a lack of breathing effort in central sleep apnea (CSA) versus continued but ineffective breathing effort in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Central sleep apnea (CSA) is characterized by repetitive cessation of breathing during sleep resulting from lack of breathing effort or drive to breathe from your brain. In obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) you can’t breathe normally because of your throat (upper airway) obstruction. Central sleep apnea is less common than obstructive sleep apnea.

- Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most common type of sleep apnea, which is characterized by partial or complete closure of your throat (upper airway) during sleep with continued respiratory effort 6. Normal breathing starts again with a snort or choking sound. Complete closure of your upper airway can lead to apnea, while partial closure allows breathing but decrease the intake of oxygen (hypopnea). Hypopnea is defined as reduction in ventilation of at least 50% that results in a decrease in arterial saturation of 4% or more due to partial airway obstruction 7, 4.

- Central sleep apnea (CSA) is a sleep disorder in which both airflow and inspiratory effort are absent or reduced due to problem in your brain that temporarily stops sending signals to the muscles that control your breathing 8, 9, 2. A single central apnea event is a ≥10-second pause in breathing with no associated respiratory effort; greater than five such events per hour are considered abnormal. Central sleep apnea is present when a patient has greater than five central apneas per hour of sleep with associated symptoms of disrupted sleep such as excessive daytime somnolence. You might awaken with shortness of breath or have a difficult time getting to sleep or staying asleep. Central sleep apnea often occurs in people who have certain medical problems. For example, it can develop in someone who has a problem with an area of the brain called the brainstem, which controls breathing. Conditions that can cause or lead to central sleep apnea include:

- Problems that affect the brainstem, including brain infection, stroke, or conditions of the cervical spine (neck)

- Certain medicines, such as narcotic painkillers

- Being at high altitude

- Treatment-emergent central sleep apnea also known as complex sleep apnea, which happens when someone has obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) converts to central sleep apnea (CSA) while using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

People with sleep apnea often snore loudly. However, not everyone who snores has sleep apnea. You are more at risk for sleep apnea if you are overweight, male, or have a family history or small airways. Children with enlarged tonsils or adenoids may also get it.

The symptoms of obstructive apnea (OSA) and central sleep apnea (CSA) overlap, sometimes making it difficult to determine which type you have. Most people with sleep apnea will have a combination of both types. The hallmark symptom of sleep apnea is excessive daytime sleepiness.

The most common symptoms of obstructive and central sleep apneas include:

- Restless sleep

- Loud snoring with periods of silence followed by gasps

- Episodes in which you stop breathing during sleep — which would be reported by another person.

- Gasping for air during sleep.

- Difficulty staying asleep, known as insomnia.

- Awakening with a dry mouth.

- Morning headache.

- Falling asleep during the day

- Excessive daytime sleepiness, known as hypersomnia.

- Trouble concentrating

- Difficulty paying attention while awake

- Irritability

- Forgetfulness

- Mood or behavior changes

- Anxiety

- Depression

Not everyone who has these symptoms will have sleep apnea, but a visit to the doctor is recommended for people experiencing even a few. Sleep apnea is more likely to occur in males than females, and in people who are overweight or obese.

When your sleep is interrupted throughout the night, you can be drowsy during the day. Left untreated, sleep apnea can be life threatening. People with sleep apnea are at higher risk for car crashes, work-related accidents, and other medical problems. Sleep apnea also appears to put individuals at risk for a major health issue associated with different forms of cardiovascular disease including high blood pressure (hypertension), coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease), heart attack, heart failure, irregular heartbeat and stroke and transient ischemic attack (TIA) also known as “mini-stroke” 10. Although there is no cure for sleep apnea, recent studies show that successful treatment can reduce the risk of heart and blood pressure problems.

Doctors diagnose sleep apnea based on medical and family histories, a physical exam, and sleep study (also called polysomnography) results. The standard test for the diagnosis of sleep apnea is polysomnography (PSG) during which patients need to sleep overnight at a sleep laboratory. However, more recently home sleep testing is increasingly being used to diagnose obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). The most commonly used type of home sleep testing device records airflow, respiratory effort, oxygen saturation, and heart rate 11. Although home sleep apnea tests are widely utilized, the accuracy of the diagnosis or severity estimation of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) with these devices is reduced 12.

If you have sleep apnea, it is important to get treatment. There are a variety of treatments for sleep apnea, depending on your medical history and the severity of your sleep apnea. Lifestyle changes, mouthpieces, surgery, and breathing devices can treat sleep apnea in many people.

Most sleep apnea treatment regimens begin with lifestyle changes, such as:

- Avoiding alcohol and medications that relax the central nervous system (e.g., sedatives and muscle relaxants)

- Losing weight

- Quitting smoking

Some people find relief when using special pillows or devices that keep them from sleeping on their backs, or oral appliances to keep the airway open during sleep. If these conservative methods are inadequate, doctors often recommend continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), in which a face mask is attached to a tube and a machine that blows pressurized air into the mask and through the airway to keep it open. Machines that offer variable positive airway pressure (VPAP) and automatic positive airway pressure (APAP) are also available.

There are surgical procedures that can be used to remove tissue and widen the airway. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a surgically implantable device, which is placed in the upper chest to monitor a person’s respiratory signals during sleep and stimulate a nerve to stimulate and restore even breathing. Some individuals may need a combination of therapies to successfully treat their sleep apnea.

Obstructive sleep apnea

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most common and potentially serious sleep-related breathing disorder where the muscles in the back of the throat intermittently relax and narrow during sleep, blocking your airway during sleep and interrupting normal breathing. These muscles support the soft palate, the triangular piece of tissue hanging from the soft palate called the uvula, the tonsils, the side walls of the throat and the tongue. When the muscles relax, your airway narrows or closes as you breathe in. You can’t get enough air, which can lower the oxygen level in your blood. Your brain senses that you can’t breathe, and briefly wakes you so that you can reopen your airway. This awakening is usually so brief that you don’t remember it. This may lead to regularly interrupted sleep, which can have a big impact on quality of life and increases the risk of developing certain health conditions.

A noticeable sign of obstructive sleep apnea is snoring. You might also snort, choke or gasp. This pattern can repeat itself 5 to 30 times or more each hour, all night. This makes it hard to reach the deep, restful phases of sleep.

Obstructive sleep apnea is most common in adult males but may also be present in women and children, though rates of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in post-menopausal women approach those of men 13, 14, 15.

In North America, the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is between 15 and 30 percent in males and 10 to 15 percent in females 16, 17. The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) varies by race, and in the United States is more prevalent in African Americans than in other groups, independent of body weight 18, 19.

The prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) also appears to be increasing, which is thought to be related to a combination of increasing rates of obesity as well as increased diagnosis and detection 1. In a study by Peppard et al. 17, it was estimated that the prevalence of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) increased from 11 to 14 percent from 1990 to 2010 among adult American males.

Central sleep apnea

Central sleep apnea is a less common form of sleep apnea in which your breathing stops over and over during sleep. Central sleep apnea results when the brain temporarily stops sending signals to the muscles that cause breathing. Central sleep apnea (CSA) is characterized by transient diminution or cessation of the respiratory rhythm generator located within the pontomedullary region of the brain 2. Central sleep apnea often occurs in people who have certain medical problems. For example, it can develop in someone who has a problem with an area of the brain called the brainstem, which controls breathing.

Conditions that can cause or lead to central sleep apnea include 2, 20, 21, 22:

- Problems that affect the brainstem, including brain infection, stroke, or conditions of the cervical spine (neck) or spinal cord injury

- Certain medicines, such as narcotic painkillers

- Being at high altitude

If the sleep apnea is not associated with another disease, it is called idiopathic central sleep apnea.

A condition called Cheyne-Stokes Breathing (CSB) can affect people with severe heart failure and can be associated with central sleep apnea. The breathing pattern involves alternating deep and heavy breathing with shallow, or even not breathing, usually while sleeping.

Central sleep apnea is not the same as obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). With obstructive sleep apnea, breathing stops and starts because the upper airway is narrowed or blocked. Central sleep apnea and obstructive sleep apnea can be present in the same person.

Though the prevalence of central sleep apnea is lower than obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), both conditions often coexist, and patients can exhibit features of both states 2. The prevalence of central sleep apnea (CSA) tends to increase with age and is higher in the elderly population above 65 years of age. A cross-sectional study reported the prevalence of central sleep apnea (CSA) in men aged 65 years and older as 2.7% by using a modified form of the International Classification of Sleep Disorders – Third Edition (ICSD-3) classification 23.

The International Classification of Sleep Disorders – Third Edition (ICSD-3) has divided central sleep apnea into several categories based on distinct clinical and polysomnographic features 24:

- Primary central sleep apnea (CSA). Diagnosis of primary central sleep apnea can be made if polysomnography (PSG) reveals ≥5 central apneas and/or central hypopneas per hour of sleep, with a total number of these central events being >50% of total respiratory events in the apnea-hypopnea index with no evidence of Cheyne-Stokes breathing (CSB) 25. Additionally, there must be at least one complaint related to disrupted sleep, i.e., sleepiness, insomnia, awakening with shortness of breath, snoring, or witnessed apneas.

- Central sleep apnea (CSA) with Cheyne-Stokes Breathing (CSB). Diagnosis of central sleep apnea with with Cheyne-Stokes Breathing (CSB) requires the criteria of primary central sleep apnea with three or more consecutive central apneas or hypopneas separated by a crescendo–decrescendo respiratory pattern with a cycle length of ≥40 seconds 2.

- Central sleep apnea (CSA) due to a medical disorder without Cheyne-Stokes Breathing (CSB)

- Central sleep apnea (CSA) due to a periodic high-altitude breathing

- Central sleep apnea (CSA) due to a medication or substance

- Treatment-emergent central sleep apnea (CSA) also known as complex sleep apnea, which happens when someone has obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) converts to central sleep apnea (CSA) while using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) therapy for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Diagnosis of treatment-emergent central apnea requires to have a primary diagnosis of OSA (with an apnea-hypopnea index [AHI] ≥ 5 obstructive respiratory events per hour of sleep) followed by resolution of the obstructive apnea and emergence or persistence of central sleep apnea (not explained by the presence of other disease or substance) during positive airway pressure (PAP) titration study 2.

Treatments for central sleep apnea involve treating existing condition that is causing central sleep apnea, using a device to assist breathing or using supplemental oxygen. Oxygen treatment may help ensure the lungs get enough oxygen while sleeping. Devices used during sleep to aid breathing may be recommended. These include nasal continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BiPAP) or adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV). Some types of central sleep apnea are treated with medicines that stimulate breathing. If narcotic medicine is causing the apnea, the dosage may need to be lowered or the medicine changed.

Sleep apnea causes

Central sleep apnea (CSA) is caused by problems with the way your brain controls your breathing while you sleep. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is caused by conditions that block airflow through your upper airways during sleep. For example, your tongue may fall backward and block your airway. Your age, family history, lifestyle habits, other medical conditions, and some features of your body can raise your risk of sleep apnea.

Many conditions can cause sleep apnea. Some factors, such as unhealthy lifestyle habits, can be changed. Other factors, such as age, family history, race and ethnicity, and sex, cannot be changed.

- Age: Sleep apnea can occur at any age, but your risk increases as you get older. As you age, fatty tissue can build up in your neck and the tongue and raise your risk of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). As you get older, normal changes in how your brain controls breathing during sleep may raise your risk of central sleep apnea (CSA).

- Endocrine disorders, or changes in your hormone levels: Your hormone levels can affect the size and shape of your face, tongue, and airway. People who have low levels of thyroid hormones or high levels of insulin or growth hormone have a higher risk of sleep apnea.

- Family history and genetics: Sleep apnea can be inherited . Your gene help determine the size and shape of your skull, face, and upper airway. Also, your genes can raise your risk of other health conditions that can lead to sleep apnea, such as cleft lip and cleft palate and Down syndrome.

- Heart or kidney failure: These conditions can cause fluid to build up in your neck, which can block your upper airway.

- Large tonsils and a thick neck: These features may cause sleep apnea because they narrow your upper airway. Also, having a large tongue and your tongue’s position in your mouth can make it easier for your tongue to block your airway while you sleep.

- Lifestyle habits: Drinking alcohol and smoking can raise your risk of sleep apnea. Alcohol can make the muscles of your mouth and throat relax, which may close your upper airway. Smoking can cause inflammation in your upper airway, which affects breathing.

- Obesity: This condition is a common cause of sleep apnea. People with this condition can have increased fat deposits in their necks that can block the upper airway. Maintaining a healthy weight can help prevent or treat sleep apnea caused by obesity.

- Sex: Sleep apnea is more common in men than in women. Men are more likely to have serious sleep apnea and to get sleep apnea at a younger age than women.

Risk factors for sleep apnea

Sleep apnea can affect anyone, even children. But certain factors increase your risk.

Factors that increase your risk of obstructive sleep apnea

Factors that increase your risk of obstructive sleep apnea include:

- Excess weight. Obesity greatly increases the risk of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Fat deposits around your upper airway can obstruct your breathing.

- Neck circumference. People with thicker necks might have narrower airways.

- A narrowed airway. You might have inherited a narrow throat. Tonsils or adenoids also can enlarge and block the airway, particularly in children.

- Being male. Men are 2 to 3 times more likely to have sleep apnea than are women. However, women increase their risk if they’re overweight or if they’ve gone through menopause.

- Being older. Sleep apnea occurs significantly more often in older adults.

- Family history. Having family members with sleep apnea might increase your risk.

- Use of alcohol, sedatives or tranquilizers. These substances relax the muscles in your throat, which can worsen obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

- Smoking. Smokers are three times more likely to have obstructive sleep apnea than are people who’ve never smoked. Smoking can increase the amount of inflammation and fluid retention in the upper airway.

- Nasal congestion. If you have trouble breathing through your nose — whether from an anatomical problem or allergies — you’re more likely to develop obstructive sleep apnea.

- Medical conditions. Congestive heart failure, high blood pressure and type 2 diabetes are some of the conditions that may increase the risk of obstructive sleep apnea. Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), hormonal disorders, prior stroke and chronic lung diseases such as asthma also can increase risk.

Factors that increase your risk of central sleep apnea

Factors that increase your risk of central sleep apnea include:

- Being older. Middle-aged and older people have a higher risk of central sleep apnea.

- Family history and genetics. Your genes can affect how your brain controls your breathing during sleep. Genetic conditions such as congenital central hypoventilation syndrome can raise your risk.

- Being male. Central sleep apnea is more common in men than it is in women.

- Drinking alcohol and smoking can affect how your brain controls sleep or the muscles involved in breathing.

- Heart disorders. Having congestive heart failure increases the risk.

- Using narcotic pain medicines. Opioid pain medicines, especially long-acting ones such as methadone an cause problems with how your brain controls sleep, increasing your risk of central sleep apnea.

- Stroke. Having had a stroke increases the risk of central sleep apnea.

- Health conditions. Some conditions that affect how your brain controls your airway and chest muscles can raise your risk. These include amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), and myasthenia gravis. Also, your hormone levels can affect how your brain controls your breathing.

- Premature birth. Babies born before 37 weeks of pregnancy have a higher risk of breathing problems during sleep. In most cases, the risk gets lower as the baby gets older.

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). Some people with obstructive sleep apnea develop central sleep apnea while using continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). This condition is known as treatment-emergent central sleep apnea or complex sleep apnea. It is a combination of obstructive and central sleep apneas. For most people, treatment-emergent central sleep apnea goes away with continued use of a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) device. Other people may be treated with a different kind of positive airway pressure therapy.

Sleep apnea prevention

You may be able to prevent obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) by making healthy lifestyle changes, such a eating a heart-healthy diet, aiming for a healthy weight, quitting smoking, and limiting alcohol intake. Your doctor also may ask you to sleep on your side and to adopt healthy sleep habits such as getting the recommended amount of sleep.

Sleep apnea signs and symptoms

Sleep apnea is a sleep disorder in which your breathing completely stops (apnea) or get very shallow episodically during sleep. These episodes usually last 10 seconds or more and occur repeatedly throughout the night. Apnea refers to a pause in your breathing for more than 10 seconds 5. Breathing pauses can last from a few seconds to minutes. Breathing pauses may occur 30 times or more an hour. People with sleep apnea will partially awaken as they struggle to breathe, but they will not be aware of the disturbances in their sleep when they wake up in the morning.

There are two categories of sleep apnea: central sleep apnea (CSA) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Central sleep apnea (CSA) and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) are differentiated by a lack of breathing effort in central sleep apnea (CSA) versus continued but ineffective breathing effort in obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). Central sleep apnea (CSA) is characterized by repetitive cessation of breathing during sleep resulting from lack of breathing effort or drive to breathe from your brain. In obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) you can’t breathe normally because of your throat (upper airway) obstruction. Central sleep apnea is less common than obstructive sleep apnea.

The symptoms of obstructive apnea (OSA) and central sleep apnea (CSA) overlap, sometimes making it difficult to determine which type you have. Most people with sleep apnea will have a combination of both types. The hallmark symptom of sleep apnea is excessive daytime sleepiness.

The most common symptoms of obstructive and central sleep apneas include:

- Restless sleep

- Loud snoring with periods of silence followed by gasps

- Episodes in which you stop breathing during sleep — which would be reported by another person.

- Gasping for air during sleep.

- Difficulty staying asleep, known as insomnia.

- Awakening with a dry mouth.

- Morning headache.

- Falling asleep during the day

- Excessive daytime sleepiness, known as hypersomnia.

- Trouble concentrating

- Difficulty paying attention while awake

- Irritability

- Forgetfulness

- Mood or behavior changes

- Anxiety

- Depression

Not everyone who has these symptoms will have sleep apnea, but a visit to the doctor is recommended for people experiencing even a few. Sleep apnea is more likely to occur in males than females, and in people who are overweight or obese.

Sleep apnea complications

Sleep apnea is a serious medical condition. Sleep apnea affects many parts of your body. It can cause low oxygen levels in your body during sleep and can prevent you from getting enough good quality sleep. Also, it takes a lot of effort for you to restart breathing many times during sleep, and this can damage your organs and blood vessels. These factors may raise your risk of the following conditions 26:

- Asthma

- Cancers, such as pancreatic cancer, kidney cancer and skin cancers

- Chronic kidney disease (CKD)

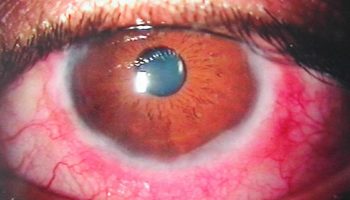

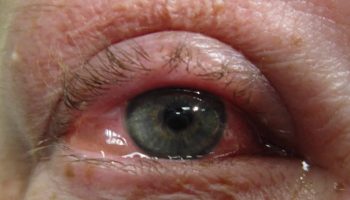

- Eye problems, such a glaucoma, dry eye, or an eye condition called keratoconus or conical cornea, a condition in which the clear tissue on the front of the eye (cornea) bulges outward

- Heart and blood vessel diseases, such as atrial fibrillation, atherosclerosis, difficult-to-control high blood pressure, heart attacks, heart failure, pulmonary hypertension, and stroke

- Metabolic syndrome

- Pregnancy complications

- Type 2 diabetes

Complications of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) can include:

- Daytime fatigue. The repeated awakenings associated with sleep apnea make typical, restorative sleep impossible, in turn making severe daytime drowsiness, fatigue and irritability likely. You might have trouble concentrating and find yourself falling asleep at work, while watching TV or even when driving. People with sleep apnea have an increased risk of motor vehicle and workplace accidents. You might also feel quick-tempered, moody or depressed. Children and adolescents with sleep apnea might perform poorly in school or have behavior problems.

- High blood pressure or heart problems. Sudden drops in blood oxygen levels that occur during obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) increase blood pressure and strain the cardiovascular system. Having obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) increases your risk of high blood pressure, also known as hypertension. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) might also increase your risk of recurrent heart attack, stroke and irregular heartbeats (arrhythmia), such as atrial fibrillation. If you have heart disease, multiple episodes of low blood oxygen (hypoxia or hypoxemia) can lead to sudden death from an irregular heartbeat.

- Type 2 diabetes. Having sleep apnea increases your risk of developing insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes.

- Metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is the name for a group of risk factors for heart disease, diabetes, and other health problems. Metabolic syndrome includes having high blood pressure, abnormal cholesterol levels (having a high triglyceride level or a low HDL “good” cholesterol level), having a high fasting blood sugar and an increased waist circumference also called abdominal obesity or “having an apple shape”, is linked to a higher risk of heart disease, diabetes, and stroke.

- Complications with medicines and surgery. Obstructive sleep apnea is also a concern with certain medicines and general anesthesia. People with sleep apnea might be more likely to have complications after major surgery because they’re prone to breathing problems, especially when sedated and lying on their backs. Before you have surgery, tell your doctor about your sleep apnea and how it’s being treated.

- Liver problems. People with sleep apnea are more likely to have irregular results on liver function tests, and their livers are more likely to show signs of scarring, known as nonalcoholic fatty liver disease.

- Sleep-deprived partners. Loud snoring can keep anyone who sleeps nearby from getting good rest. It’s common for a partner to have to go to another room, or even to another floor of the house, to be able to sleep.

Complications of central sleep apnea (CSA) can include:

- Fatigue. The repeated awakening associated with sleep apnea makes typical, restorative sleep impossible. People with central sleep apnea often have severe fatigue, daytime drowsiness and irritability. You might have difficulty concentrating and find yourself falling asleep at work, while watching television or even while driving.

- Cardiovascular problems. Sudden drops in blood oxygen levels also called known as hypoxia or hypoxemia that occur during central sleep apnea can adversely affect heart health. If there’s underlying heart disease, these repeated multiple episodes of low blood oxygen worsen prognosis and increase the risk of irregular heart rhythms.

Sleep apnea diagnosis

Your doctor will ask you about your symptoms, risk factors, and whether you have a family history of sleep apnea. You may need a sleep study also called polysomnography to help diagnose sleep apnea. Your doctor will ask you to see a sleep specialist or go to a center for a sleep study. The most common type of sleep studies record brain waves and monitor your heart rate, breathing, and the oxygen level in your blood during a full night of sleep (nocturnal polysomnography). Sleep studies (polysomnography) can help diagnose which type of sleep apnea you have and how serious it is. Sleep studies (polysomnography) can also help your doctor diagnose sleep-related seizure disorders, sleep-related movement disorders, and sleep disorders that cause extreme daytime tiredness such as narcolepsy. Doctors also may use sleep tests to help diagnose or rule out restless legs syndrome.

It may also help to fill out an Epworth Sleepiness Scale questionnaire. This asks how likely you’ll be to doze off in a number of different situations, such as watching TV or sitting in a meeting. The final score will help your doctor determine whether you may have a sleep disorder. For example, a score of 16-24 means you’re excessively sleepy and should consider seeking medical attention. A score of eight to nine is considered average during the daytime.

Figure 1. Epworth Sleepiness Scale

Sleep apnea testing

You’re likely to be referred to a sleep disorder center. There, a sleep specialist can help you determine your need for further evaluation.

An evaluation often involves overnight monitoring of your breathing and other body functions during sleep testing at a sleep center. Home sleep testing also might be an option. Tests to detect sleep apnea include:

- Nocturnal polysomnography. During this test, you’re hooked up to equipment that monitors your heart, lung and brain activity, breathing patterns, arm and leg movements, and blood oxygen levels while you sleep.

- Home sleep tests. Your sleep specialist might provide you with simplified tests to be used at home to diagnose sleep apnea. These tests usually measure your heart rate, blood oxygen level, airflow and breathing patterns. Your sleep specialist is more likely to recommend polysomnography in a sleep testing facility, rather than a home sleep test, if central sleep apnea (CSA) is suspected.

If your results abnormal, your sleep specialist might be able to prescribe a therapy without further testing. Portable monitoring devices sometimes miss sleep apnea. So your sleep specialist might still recommend polysomnography even if your first results are within the standard range.

If you have obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), your sleep specialist might refer you to an ear, nose and throat (ENT) specialist to rule out a blockage in your nose or throat. An evaluation by a heart specialist, known as a cardiologist, or a doctor who specializes in the nervous system, called a neurologist, might be necessary to look for causes of central sleep apnea (CSA).

Determining the severity of obstructive sleep apnea

The severity of obstructive sleep apnea is determined by how often your breathing is affected over the course of an hour. These episodes are measured using the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI).

Severity is measured using the following criteria:

- Mild obstructive sleep apnea – an apnea-hypopnea index reading of 5 to 14 episodes an hour

- Moderate obstructive sleep apnea – an apnea-hypopnea index reading of 15 to 30 episodes an hour

- Severe obstructive sleep apnea – an apnea-hypopnea index reading of more than 30 episodes an hour

Current evidence suggests treatment is most likely to be beneficial in people with moderate or severe obstructive sleep apnea. However, some research has suggested treatment may also help some people with mild obstructive sleep apnea.

Ruling out other medical conditions

Your sleep specialist may order other tests to help rule out other medical conditions that can cause sleep apnea.

- Blood tests check the levels of certain hormones to check for endocrine disorders that could contribute to sleep apnea. Thyroid hormones tests can rule out hypothyroidism. Growth hormone tests can rule out acromegaly. Total testosterone and dehydroepiandrosterone sulphate (DHEAS) tests can help rule out polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

- Pelvic ultrasounds examine the ovaries and help detect cysts. This can rule out polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

Your doctor will also want to know whether you are using medicines, such as opioids, that could affect your sleep or cause breathing symptoms of sleep apnea. Your doctor may want to know whether you have traveled recently to altitudes greater than 6,000 feet, because these low-oxygen environments can cause symptoms of sleep apnea for a few weeks after traveling.

Sleep apnea treatment

There are a variety of treatments for sleep apnea, depending on your medical history, condition and the severity of your sleep apnea. Lifestyle changes, mouthpieces, surgery, and breathing devices can treat sleep apnea in many people.

Most sleep apnea treatment regimens begin with lifestyle changes, such as:

- Avoiding alcohol and medications that relax the central nervous system (e.g., sedatives and muscle relaxants)

- Losing weight

- Quitting smoking

You may need to change the position in which you sleep. Some people find relief when using special pillows or devices that keep them from sleeping on their backs, or oral appliances to keep the airway open during sleep. If you have nasal allergies, your doctor may recommend treatment for your allergies. If these conservative methods are inadequate, doctors often recommend continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), in which a face mask is attached to a tube and a machine that blows pressurized air into the mask and through the airway to keep it open. Machines that offer variable positive airway pressure (VPAP) and automatic positive airway pressure (APAP) are also available.

There are surgical procedures that can be used to remove tissue and widen the airway. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved a surgically implantable device, which is placed in the upper chest to monitor a person’s respiratory signals during sleep and stimulate a nerve to stimulate and restore even breathing. Some individuals may need a combination of therapies to successfully treat their sleep apnea.

Healthy lifestyle changes

To help treat your sleep apnea, healthy lifestyle changes can be very effective. Healthy lifestyle include getting regular physical activity, maintaining healthy sleeping habits and a healthy weight, limiting alcohol and caffeine intake, and quitting smoking. Your doctor may also recommend that you sleep on your side — not on your back — as this can help keep your airway open while you sleep.

Obstructive sleep apnea treatment

If you have moderate to severe obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), you might benefit from using a machine that delivers air pressure through a mask while you sleep. A breathing device, such as a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) machine, is the most common treatment for sleep apnea. A CPAP machine provides constant air pressure throughout your upper airways to keep them open and help you breathe while you sleep. Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) work best when they are paired with healthy lifestyle changes.

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP)

With continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), the air pressure is somewhat greater than that of the surrounding air and is just enough to keep your upper airway passages open, preventing apnea and snoring.

Side effects of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) treatment may include:

- Congestion

- Dry eyes

- Dry mouth

- Nosebleeds

- Runny nose

If you experience stomach discomfort or bloating, you should stop using your CPAP machine and contact your doctor. Depending on the type of sleep apnea you have, you may need another type of breathing device, such as an auto-adjusting positive airway pressure (APAP) machine or a bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) machine. It’s recommended that you discuss the most appropriate breathing device for you with your sleep specialist.

Although continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the most common and reliable method of treating sleep apnea, some people find it cumbersome or uncomfortable. Some people give up on the CPAP machine. But with practice, most people learn to adjust the tension of the straps on the mask to obtain a comfortable and secure fit.

You might need to try more than one type of mask to find one that’s comfortable. Don’t stop using the CPAP machine if you have problems. Check with your doctor to see what changes can be made to increase your comfort.

Additionally, contact your doctor if you’re still snoring or begin snoring again despite treatment. If your weight changes, the pressure settings of the CPAP machine might need to be adjusted.

Sleep apnea masks

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) masks and headgear come in many styles and sizes to comfortably treat your sleep apnea. Everyone has different needs, preferences and face shapes, and sometimes you will need to try different mask styles before you find the one that works the best for you.

Sizes may vary across different CPAP mask styles and brands. You may need to try on several styles and sizes to find the best combination of comfort and efficiency.

For example, if you take a small in one type it does not necessarily mean you will need a small in a different brand. Proper sizing is very important to comfort and performance of CPAP masks.

Work with your doctor and CPAP mask supplier to make sure you have a mask that suits your needs and fits you properly.

Nasal pillow CPAP mask

Nasal pillow CPAP mask fits at the nostrils to supply air pressure. Nasal pillow CPAP masks might be good if:

- You feel claustrophobic in masks that cover more of your face.

- You want a full field of vision for reading or watching TV.

- You want to wear your glasses.

- You have facial hair that interferes with other masks.

Figure 2. Nasal pillow CPAP mask

Nasal CPAP masks

Nasal CPAP masks cover your nose to supply air pressure. Nasal CPAP masks might be good if:

- Your doctor has prescribed a high air pressure setting.

- You move around a lot in your sleep.

Figure 3. Nasal CPAP masks

Full-face CPAP masks

Full-face CPAP masks also called oronasal CPAP masks cover your nose and mouth to supply air pressure. Full-face CPAP masks might be a good choice if:

- You have nasal blockage or congestion that makes it hard to breathe through your nose.

- You breathe through your mouth at night despite a month of trying a nasal mask or nasal pillow. A nasal mask or nasal pillow are typically combined with a heated humidity feature, a chin strap or both to keep your mouth closed.

Figure 4. Full-face CPAP masks

Oral CPAP masks

Oral CPAP masks also known as a hybrid CPAP masks deliver air pressure through your mouth. Oral CPAP masks might be right for you if:

- You breathe through your mouth.

- You wear eyeglasses.

Figure 5. Oral CPAP mask

Other airway pressure devices

If using a CPAP machine continues to be a problem for you, you might be able to use a different type of airway pressure device that automatically adjusts the pressure while you’re sleeping (auto-CPAP). Units that supply bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) also are available. These provide more pressure when you inhale and less when you exhale.

Sleep apnea oral devices

If you have sleep apnea, your doctor may prescribe an oral device (also called oral appliance) to keep your throat open if you do not want to use or cannot tolerate continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). You may be referred to a dentist who custom-fits a device to your mouth so that it is comfortable and teaches you how to use it for best results.

Some oral devices are designed to open your throat by bringing your jaw forward, which can sometimes relieve snoring and mild obstructive sleep apnea.

A number of oral devices are available from your dentist. You might need to try different oral devices before finding one that works for you. Once you find the right fit, you’ll need to follow up with your dentist repeatedly during the first year and then regularly after that to ensure that the fit is still good and to reassess your symptoms.

Two types of oral devices work differently to open the upper airway while you sleep:

- Mandibular repositioning mouthpieces are devices that cover the upper and lower teeth and hold the lower jaw in a position that prevents it from sliding backward and blocking the upper airway.

- Tongue-retaining devices are mouthpieces that hold the tongue in a forward position to prevent it from blocking the upper airway.

There are other devices that combine these features and/or use electrical stimulation to keep your upper airways open during sleep.

- Neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) devices are removable devices that stimulate and tone the tongue and upper airway muscles to prevent them from collapsing and blocking the airway during sleep.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved an neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) oral device for use while awake 27. The neuromuscular electrical stimulation (NMES) device delivers electrical muscle stimulation through a removable mouthpiece that sits around the tongue. You wear the mouthpiece once a day for 20 minutes at a time, for six weeks. This device is approved for people with mild obstructive sleep apnea.

You’ll likely read, hear or see TV ads about different treatments for sleep apnea. Talk with your doctor about any treatment before you try it.

Surgery for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA)

Surgery may be an option for people with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), but usually only after other treatments have failed. Generally, at least a three-month trial of other treatment options is suggested before considering surgery. However, for a small number of people with certain jaw structure problems, surgery is a good first option.

Surgical options might include:

- Tissue removal. During this procedure (uvulopalatopharyngoplasty), a surgeon removes tissue from the rear of your mouth and top of the throat. Your tonsils and adenoids usually are removed as well. This type of surgery might be successful in stopping throat structures from vibrating and causing snoring. It’s less effective than CPAP and isn’t considered a reliable treatment for obstructive sleep apnea. Removing tissues in the back of the throat with radiofrequency energy (radiofrequency ablation) might be an option for those who can’t tolerate CPAP or oral appliances.

- Tissue shrinkage. Another option is to shrink the tissue at the rear of the mouth and the back of the throat using radiofrequency ablation. This procedure might be used for mild to moderate sleep apnea. One study found this to have effects similar to that of tissue removal, but with fewer surgical risks.

- Jaw repositioning also known as maxillomandibular advancement. In this procedure, the jaw is moved forward from the remainder of the face bones. This enlarges the space behind the tongue and soft palate, making obstruction less likely.

- Implants. Soft rods, usually made of polyester or plastic, are surgically implanted into the soft palate after numbing with a local anesthetic. More research is needed to determine how well implants work.

- Nerve stimulation. This requires surgery to insert a stimulator for the nerve that controls tongue movement (hypoglossal nerve). The increased stimulation helps keep the tongue in a position that keeps the airway open. More research is needed.

- Creating a new air passageway also known as tracheostomy. You may need this form of surgery if other treatments have failed and you have severe, life-threatening sleep apnea. In this procedure, your surgeon makes an opening in your neck and inserts a metal or plastic tube through which you breathe. You keep the opening covered during the day. But at night you uncover it to allow air to pass in and out of your lungs, bypassing the blocked air passage in your throat.

Other types of surgery may help reduce snoring and contribute to the treatment of sleep apnea by clearing or enlarging air passages:

- Surgery to remove enlarged tonsils and adenoids (adenotonsillectomy).

- Weight-loss surgery, also known as bariatric surgery.

Therapy for your mouth and facial muscles

Exercises for your mouth and facial muscles, called orofacial therapy, may also be an effective treatment for obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in children and adults. This therapy helps to strengthen and reposition the tongue and muscles that control your lips, tongue, upper airway, and face.

Central sleep apnea treatment

Possible causes of central sleep apnea (CSA) include heart or neuromuscular disorders, and treating those conditions might help your sleep apnea. Other therapies that may be used for central sleep apnea (CSA) include supplemental oxygen, continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP), and adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV).

You may be prescribed medicine to help manage your breathing, such as acetazolamide. If medicines are worsening your central sleep apnea (CSA), such as opioids, your doctor may change your medicines.

Using supplemental oxygen while you sleep might help if you have central sleep apnea. Various forms of oxygen are available with devices to deliver oxygen to your lungs.

Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) is recently approved airflow device that learns your typical breathing pattern and stores the information in a built-in computer. After you fall asleep, the adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) machine uses pressure to regulate your breathing pattern and prevent pauses in your breathing. Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) may be an option for some people with treatment-emergent central sleep apnea. However, it might not be a good choice for people with predominant central sleep apnea and advanced heart failure. And adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) is not recommended for those with severe heart failure.

Central sleep apnea treatments may include:

- Addressing associated medical problems. Possible causes of central sleep apnea include other disorders, and treating those conditions may help your central sleep apnea. For example, if central sleep apnea is due to heart failure, the goal is to treat the heart failure itself.

- Reduction of opioid medications. If opioid medications are causing your central sleep apnea, your doctor may gradually reduce your dose of those medications.

- Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). This method, also used to treat obstructive sleep apnea, involves wearing a mask over your nose or your nose and mouth while you sleep. CPAP is usually the first treatment given for central sleep apnea. The mask is attached to a small pump that supplies a continuous amount of pressurized air to hold open your upper airway. CPAP may prevent the airway closure that can trigger central sleep apnea. As with obstructive sleep apnea, it’s important that you use the device only as directed. If your mask is uncomfortable or the pressure feels too strong, talk with your doctor. Several types of masks are available. Doctors can also adjust the air pressure.

- Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV). If CPAP hasn’t effectively treated your condition, you may be given adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV). Like CPAP, adaptive servo-ventilation also delivers pressurized air. Unlike CPAP, adaptive servo-ventilation adjusts the amount of pressure during inhalation on a breath-by-breath basis to smooth out the breathing pattern. The device may also automatically deliver a breath if you haven’t taken a breath within a certain number of seconds. Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) isn’t recommended for people with symptomatic heart failure 28. A multicenter largest trial (SERVE-HF) revealed that the use of adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) was associated with increased the risk of death in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction 29. Therefore, adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) is not recommended for the treatment of central sleep apnea in people with heart failure.

- Bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP). Like adaptive servo-ventilation, bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) delivers pressure when you breathe in and a different amount of pressure when you breathe out. Unlike adaptive servo-ventilation, the amount of pressure during inspiration is fixed rather than variable. Bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) can also be configured to deliver a breath if you haven’t taken a breath within a certain number of seconds. Dohi et al. 30 suggested the effectiveness of BPAP in patients with heart failure and central sleep apnea with Cheyne-Stokes Breathing (CSB). BPAP acts to normalize the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) by increasing ventilation and augmenting alveolar volume. A longitudinal cross-section study also suggested using CPAP and BiPAP to treat opioid-related central sleep apnea 31. Be sure to talk to your doctor about the potential risks of BPAP if your doctor is considering this therapy and you have heart failure.

- Supplemental oxygen. Using supplemental oxygen while you sleep may help if you have central sleep apnea. Various devices are available to deliver oxygen to your lungs.

- Medications. Certain medications, such as acetazolamide (Diamox) or theophylline (Theo-24, Theochron), have been used to stimulate breathing in people with central sleep apnea. These medications may be prescribed to help your breathing as you sleep if you can’t tolerate positive airway pressure. These medications may also be used to prevent central sleep apnea in high altitude.

Central sleep apnea mechanical devices

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) has been recommended as the first-line therapy for central sleep apnea (CSA). Available literature and data support CPAP’s beneficial effect on central sleep apnea 32, 33. It can be explained by its ability to maintain airway patency, stabilizing the compensatory ventilatory output. In concurrent obstructive episodes, CPAP is a reasonable therapeutic option. The Canadian CPAP (CANPAP) trial was the most extensive randomized controlled study to evaluate the effect of CPAP on morbidity and mortality in patients with central sleep apnea (CSA) and heart failure 34. The study did reveal a modest reduction in mean apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) to 19 events per hour of sleep without significant effect on mortality. A subsequent post hoc analysis (a statistical analysis specified after a study has been concluded and the data collected) showed a reduction in mortality rate in those patients who responded to CPAP therapy 35.

Bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) can be a viable option in hypercapnic central sleep apnea, especially if the patient is unresponsive to CPAP. Dohi et al. 30 suggested the effectiveness of bilevel positive airway pressure (BPAP) in patients with heart failure and central sleep apnea (CSA) with Cheyne-Stokes Breathing (CSB). Bi-level positive airway pressure ventilation (BPAP) acts to normalize the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) by increasing ventilation and augmenting alveolar volume. A longitudinal cross-section study also suggested using CPAP and BPAP to treat opioid-related central sleep apnea (CSA) 31

Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) is a form of positive airway pressure that provides ventilatory support individualized to the patient’s effort. A servo-controlled inspiratory pressure is delivered over positive end-expiratory pressure based on the detection of apneas. It remains a therapeutic option for central sleep apnea (CSA) patients with preserved ejection fraction and improves AHI and left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) 28. A multicenter largest trial (SERVE-HF) revealed that the use of adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) was associated with increased mortality in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction 29. Therefore, adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) is not recommended for the treatment of central sleep apnea (CSA) in this particular group of patients 29.

Nocturnal oxygen therapy in previous trials has decreased the number of apneic episodes during sleep times for patients with congestive heart failure. It also improved NYHA functional class quality of life, and ejection fraction was noted at the end of 12-week in patients with central sleep apnea (CSA) 36. These findings were confirmed over 52 weeks in a similar trial, ensuring improved quality of life 37.

Unilateral placement of phrenic nerve stimulators is another treatment option for patients with central sleep apnea (CSA). A recent study suggested that phrenic nerve stimulation therapy was associated with decreased disease severity and improved quality of life 38. It also resulted in significant improvement in the arousal index, improved quality of life, and a decreased self-reported daytime sleepiness. These benefits were independent of heart failure status 38. Peripheral nerve stimulation works by restoring the normal physiological mechanics of breathing.

Different medications have been studied as a potential treatment for central sleep apnea. However, these medications remain investigational, and there is no approved pharmacological treatment for central sleep apnea (CSA). Hypnotics such as triazolam and zolpidem can reduce wakefulness and unstable sleep 39. These medications may lead to increased total sleep, decreased central apnea index, and a decrease in brief arousals 39.

Respiratory stimulants such as acetazolamide, a carbonic anhydrase inhibitor, work by causing mild metabolic acidosis, resulting in increased respiratory drive decreases the frequency of central apneas 40. Recently, other medications such as Buspirone and Mirtazapine have been studied 41, 42. Both drugs reduced the susceptibility to developing hypocapnic central apnea in individuals with spinal cord injuries. Theophylline, a non-selective adenosine receptors antagonist, has been used in the context of central sleep apneas in patients with heart failure, and the benefit may be attributed to inhibition of adenosine receptors located in the medulla leading to increasing ventilatory stimulation 43. A recent experimental study demonstrated that selective adenosine A1 receptor blockade could alleviate the cervical spinal cord injury sleep disordered breathing to significantly reduce apnea-hypopnea index following induced cervical spinal cord injury in rats 44.

Sleep apnea monitoring

If you have been diagnosed with sleep apnea, you will need to schedule regular check-ups to make sure that your treatment is working and whether you have any complications. You may need to repeat your sleep study to monitor your symptoms while using your treatment, especially if you gain or lose a lot of weight. You may also need treatment for other health conditions that caused your sleep apnea or can make it worse.

Sleep apnea prognosis

Undiagnosed or untreated sleep apnea prevents you from getting enough rest, which can cause problems concentrating, remembering things, making decisions, or controlling your behavior, as well as dementia in older adults. In children, sleep apnea can lead to problems with learning and memory, known as learning disabilities. The daytime sleepiness and fatigue that results from sleep apnea can also impact your child’s behavior and their desire to be physically active.

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) prognosis

The short-term prognosis of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) with treatment is good, but the long-term prognosis is guarded 3. The biggest problem is the lack of adherence to CPAP, as nearly 50% of patients stop using CPAP within the first month despite education 45. Many patients have two or more other medical conditions on top of sleep apnea or are at risk for adverse heart events and stroke. Therefore, those who do not use CPAP are at increased risk of heart and brain adverse events in addition to higher annual healthcare-related expenses 46, 47.

Furthermore, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is also associated with pulmonary hypertension, hypercapnia, hypoxemia, and daytime sedation, and these individuals have a high risk of motor vehicle accidents 3. The overall life expectancy of patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is lower than the general population 3. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is known to affect heart function, particularly in obese individuals 48, 49. CPAP treatment was recently found to improve left and right ventricular mechanics in patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) 50.

Cantral sleep apnea (CSA) prognosis

Patients with sleep apnea syndrome are at increased risk of systemic complications, including systemic hypertension, pulmonary hypertension, arrhythmias including atrial fibrillation, sleep disturbances accompanied with excessive daytime sleepiness, mood disorders, chronic respiratory failure, narcolepsy, and hypercapnic respiratory failure 51. Heart failure patients with central sleep apnea (CSA) and Cheyne-Stokes breathing tend to have a worse prognosis, and treatment often includes optimization of heart failure therapy 52.

Adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) is a therapy modality that delivers servo-controlled inspiratory pressure support on top of expiratory positive airway pressure. A recent study in 2015 showed that in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction, adaptive servo-ventilation (ASV) was associated with increased all-cause and cardiovascular mortality without any significant benefit 2. There was no improvement in either symptoms or quality of life 53. There has been reportedly increased mortality in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction in whom adaptive servo-ventilation was used 54.

- Cumpston E, Chen P. Sleep Apnea Syndrome. [Updated 2023 Sep 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK564431[↩][↩]

- Rana AM, Sankari A. Central Sleep Apnea. [Updated 2023 Jun 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK578199[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Slowik JM, Sankari A, Collen JF. Obstructive Sleep Apnea. [Updated 2024 Mar 21]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459252[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- US Preventive Services Task Force; Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, Curry SJ, Davidson KW, Epling JW Jr, García FA, Herzstein J, Kemper AR, Krist AH, Kurth AE, Landefeld CS, Mangione CM, Phillips WR, Phipps MG, Pignone MP, Silverstein M, Tseng CW. Screening for Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA. 2017 Jan 24;317(4):407-414. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.20325[↩][↩]

- Mbata G, Chukwuka J. Obstructive sleep apnea hypopnea syndrome. Ann Med Health Sci Res. 2012;2(1):74–77. doi:10.4103/2141-9248.96943 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3507119[↩][↩]

- Jordan AS, McSharry DG, Malhotra A. Adult obstructive sleep apnoea. Lancet. 2014 Feb 22;383(9918):736-47. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60734-5[↩]

- Sleep apnoea: What Is Sleep Apnoea? NHLBI: Health information for the public. U S Department of Health and Human services. 2009 May; Assessed from internet on 20th November, 2010[↩]

- Dempsey JA, Veasey SC, Morgan BJ, O’Donnell CP. Pathophysiology of sleep apnea. Physiol Rev. 2010 Jan;90(1):47-112. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00043.2008. Erratum in: Physiol Rev.2010 Apr;90(2):797-8.[↩]

- Wellman A, Jordan AS, Malhotra A, Fogel RB, Katz ES, Schory K, Edwards JK, White DP. Ventilatory control and airway anatomy in obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004 Dec 1;170(11):1225-32. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-510OC[↩]

- Tietjens JR, Claman D, Kezirian EJ, De Marco T, Mirzayan A, Sadroonri B, Goldberg AN, Long C, Gerstenfeld EP, Yeghiazarians Y. Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Cardiovascular Disease: A Review of the Literature and Proposed Multidisciplinary Clinical Management Strategy. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019 Jan 8;8(1):e010440. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010440[↩]

- Bazoukis G, Bollepalli SC, Chung CT, Li X, Tse G, Bartley BL, Batool-Anwar S, Quan SF, Armoundas AA. Application of artificial intelligence in the diagnosis of sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2023 Jul 1;19(7):1337-1363. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.10532[↩]

- Kapoor M, Greenough G. Home Sleep Tests for Obstructive Sleep Apnea (OSA). J Am Board Fam Med. 2015 Jul-Aug;28(4):504-9. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2015.04.140266[↩]

- Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993 Apr 29;328(17):1230-5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704[↩]

- Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Lin HM, Ten Have T, Rein J, Vela-Bueno A, Kales A. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in women: effects of gender. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001 Mar;163(3 Pt 1):608-13. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.9911064[↩]

- Bixler EO, Vgontzas AN, Ten Have T, Tyson K, Kales A. Effects of age on sleep apnea in men: I. Prevalence and severity. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998 Jan;157(1):144-8. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.1.9706079[↩]

- Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Peppard PE, Nieto FJ, Hla KM. Burden of sleep apnea: rationale, design, and major findings of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort study. WMJ. 2009 Aug;108(5):246-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2858234[↩]

- Peppard PE, Young T, Barnet JH, Palta M, Hagen EW, Hla KM. Increased prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in adults. Am J Epidemiol. 2013 May 1;177(9):1006-14. doi: 10.1093/aje/kws342[↩][↩]

- Redline S, Tishler PV, Hans MG, Tosteson TD, Strohl KP, Spry K. Racial differences in sleep-disordered breathing in African-Americans and Caucasians. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997 Jan;155(1):186-92. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.155.1.9001310. Erratum in: Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997 May;155(5):1820.[↩]

- Ancoli-Israel S, Klauber MR, Stepnowsky C, Estline E, Chinn A, Fell R. Sleep-disordered breathing in African-American elderly. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995 Dec;152(6 Pt 1):1946-9. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.152.6.8520760[↩]

- Sankari A, Bascom A, Oomman S, Badr MS. Sleep disordered breathing in chronic spinal cord injury. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014 Jan 15;10(1):65-72. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3362[↩]

- Sankari A, Bascom AT, Chowdhuri S, Badr MS. Tetraplegia is a risk factor for central sleep apnea. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014 Feb 1;116(3):345-53. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00731.2013. Epub 2013 Oct 10. Erratum in: J Appl Physiol (1985). 2014 Oct 15;117(8):940.[↩]

- Javaheri S, Barbe F, Campos-Rodriguez F, Dempsey JA, Khayat R, Javaheri S, Malhotra A, Martinez-Garcia MA, Mehra R, Pack AI, Polotsky VY, Redline S, Somers VK. Sleep Apnea: Types, Mechanisms, and Clinical Cardiovascular Consequences. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Feb 21;69(7):841-858. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2016.11.069[↩]

- Donovan LM, Kapur VK. Prevalence and Characteristics of Central Compared to Obstructive Sleep Apnea: Analyses from the Sleep Heart Health Study Cohort. Sleep. 2016 Jul 1;39(7):1353-9. doi: 10.5665/sleep.5962[↩]

- Sateia MJ. International classification of sleep disorders-third edition: highlights and modifications. Chest. 2014 Nov;146(5):1387-1394. doi: 10.1378/chest.14-0970[↩]

- Berry RB, Brooks R, Gamaldo C, Harding SM, Lloyd RM, Quan SF, Troester MT, Vaughn BV. AASM Scoring Manual Updates for 2017 (Version 2.4). J Clin Sleep Med. 2017 May 15;13(5):665-666. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6576[↩]

- Living With Sleep Apnea. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/sleep-apnea/living-with[↩]

- FDA Authorizes Marketing of Novel Device to Reduce Snoring and Mild Obstructive Sleep Apnea in Patients 18 Years and Older. https://www.fda.gov/news-events/press-announcements/fda-authorizes-marketing-novel-device-reduce-snoring-and-mild-obstructive-sleep-apnea-patients-18[↩]

- Aurora RN, Chowdhuri S, Ramar K, Bista SR, Casey KR, Lamm CI, Kristo DA, Mallea JM, Rowley JA, Zak RS, Tracy SL. The treatment of central sleep apnea syndromes in adults: practice parameters with an evidence-based literature review and meta-analyses. Sleep. 2012 Jan 1;35(1):17-40. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1580[↩][↩]

- Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, Angermann C, d’Ortho MP, Erdmann E, Levy P, Simonds AK, Somers VK, Zannad F, Teschler H. Adaptive Servo-Ventilation for Central Sleep Apnea in Systolic Heart Failure. N Engl J Med. 2015 Sep 17;373(12):1095-105. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1506459[↩][↩][↩]

- Dohi T, Kasai T, Narui K, Ishiwata S, Ohno M, Yamaguchi T, Momomura S. Bi-level positive airway pressure ventilation for treating heart failure with central sleep apnea that is unresponsive to continuous positive airway pressure. Circ J. 2008 Jul;72(7):1100-5. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.1100[↩][↩]

- Schoebel C, Ghaderi A, Amra B, Soltaninejad F, Penzel T, Fietze I. Comparison of Therapeutic Approaches to Addicted Patients with Central Sleep Apnea. Tanaffos. 2018 Mar;17(3):155-162. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6428378[↩][↩]

- Hoffstein V, Slutsky AS. Central sleep apnea reversed by continuous positive airway pressure. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987 May;135(5):1210-2. doi: 10.1164/arrd.1987.135.5.1210[↩]

- Sin DD, Logan AG, Fitzgerald FS, Liu PP, Bradley TD. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on cardiovascular outcomes in heart failure patients with and without Cheyne-Stokes respiration. Circulation. 2000 Jul 4;102(1):61-6. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.1.61[↩]

- Bradley TD, Logan AG, Kimoff RJ, Sériès F, Morrison D, Ferguson K, Belenkie I, Pfeifer M, Fleetham J, Hanly P, Smilovitch M, Tomlinson G, Floras JS; CANPAP Investigators. Continuous positive airway pressure for central sleep apnea and heart failure. N Engl J Med. 2005 Nov 10;353(19):2025-33. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa051001[↩]

- Arzt M, Floras JS, Logan AG, Kimoff RJ, Series F, Morrison D, Ferguson K, Belenkie I, Pfeifer M, Fleetham J, Hanly P, Smilovitch M, Ryan C, Tomlinson G, Bradley TD; CANPAP Investigators. Suppression of central sleep apnea by continuous positive airway pressure and transplant-free survival in heart failure: a post hoc analysis of the Canadian Continuous Positive Airway Pressure for Patients with Central Sleep Apnea and Heart Failure Trial (CANPAP). Circulation. 2007 Jun 26;115(25):3173-80. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.683482[↩]

- Sakakibara M, Sakata Y, Usui K, Hayama Y, Kanda S, Wada N, Matsui Y, Suto Y, Shimura S, Tanabe T. Effectiveness of short-term treatment with nocturnal oxygen therapy for central sleep apnea in patients with congestive heart failure. J Cardiol. 2005 Aug;46(2):53-61.[↩]

- Sasayama S, Izumi T, Matsuzaki M, Matsumori A, Asanoi H, Momomura S, Seino Y, Ueshima K; CHF-HOT Study Group. Improvement of quality of life with nocturnal oxygen therapy in heart failure patients with central sleep apnea. Circ J. 2009 Jul;73(7):1255-62. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-08-1210[↩]

- Fudim M, Spector AR, Costanzo MR, Pokorney SD, Mentz RJ, Jagielski D, Augostini R, Abraham WT, Ponikowski PP, McKane SW, Piccini JP. Phrenic Nerve Stimulation for the Treatment of Central Sleep Apnea: A Pooled Cohort Analysis. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019 Dec 15;15(12):1747-1755. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.8076[↩][↩]

- Bonnet MH, Dexter JR, Arand DL. The effect of triazolam on arousal and respiration in central sleep apnea patients. Sleep. 1990 Feb;13(1):31-41. doi: 10.1093/sleep/13.1.31[↩][↩]

- Ginter G, Sankari A, Eshraghi M, Obiakor H, Yarandi H, Chowdhuri S, Salloum A, Badr MS. Effect of acetazolamide on susceptibility to central sleep apnea in chronic spinal cord injury. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2020 Apr 1;128(4):960-966. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00532.2019[↩]

- Prowting J, Maresh S, Vaughan S, Kruppe E, Alsabri B, Badr MS, Sankari A. Mirtazapine reduces susceptibility to hypocapnic central sleep apnea in males with sleep-disordered breathing: a pilot study. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2021 Jul 1;131(1):414-423. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00838.2020[↩]

- Maresh S, Prowting J, Vaughan S, Kruppe E, Alsabri B, Yarandi H, Badr MS, Sankari A. Buspirone decreases susceptibility to hypocapnic central sleep apnea in chronic SCI patients. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2020 Oct 1;129(4):675-682. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00435.2020[↩]

- Javaheri S, Parker TJ, Wexler L, Liming JD, Lindower P, Roselle GA. Effect of theophylline on sleep-disordered breathing in heart failure. N Engl J Med. 1996 Aug 22;335(8):562-7. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199608223350805[↩]

- Sankari A, Minic Z, Farshi P, Shanidze M, Mansour W, Liu F, Mao G, Goshgarian HG. Sleep disordered breathing induced by cervical spinal cord injury and effect of adenosine A1 receptors modulation in rats. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2019 Dec 1;127(6):1668-1676. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00563.2019[↩]

- Guralnick AS, Balachandran JS, Szutenbach S, Adley K, Emami L, Mohammadi M, Farnan JM, Arora VM, Mokhlesi B. Educational video to improve CPAP use in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea at risk for poor adherence: a randomised controlled trial. Thorax. 2017 Dec;72(12):1132-1139. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210106[↩]

- Marshall NS, Wong KK, Cullen SR, Knuiman MW, Grunstein RR. Sleep apnea and 20-year follow-up for all-cause mortality, stroke, and cancer incidence and mortality in the Busselton Health Study cohort. J Clin Sleep Med. 2014 Apr 15;10(4):355-62. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.3600[↩]

- Bock JM, Needham KA, Gregory DA, Ekono MM, Wickwire EM, Somers VK, Lerman A. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure Adherence and Treatment Cost in Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Cardiovascular Disease. Mayo Clin Proc Innov Qual Outcomes. 2022 Apr 4;6(2):166-175. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocpiqo.2022.01.002[↩]

- Alkatib S, Sankri-Tarbichi AG, Badr MS. The impact of obesity on cardiac dysfunction in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breath. 2014 Mar;18(1):137-42. doi: 10.1007/s11325-013-0861-0[↩]

- Saeed S, Romarheim A, Solheim E, Bjorvatn B, Lehmann S. Cardiovascular remodeling in obstructive sleep apnea: focus on arterial stiffness, left ventricular geometry and atrial fibrillation. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2022 Jun;20(6):455-464. doi: 10.1080/14779072.2022.2081547[↩]

- Tadic M, Gherbesi E, Faggiano A, Sala C, Carugo S, Cuspidi C. The impact of continuous positive airway pressure on cardiac mechanics: Findings from a meta-analysis of echocardiographic studies. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2022 Jul;24(7):795-803. doi: 10.1111/jch.14488[↩]

- Chaudhary BA, Speir WA Jr. Sleep apnea syndromes. South Med J. 1982 Jan;75(1):39-45. doi: 10.1097/00007611-198201000-00011[↩]

- Terziyski K, Draganova A. Central Sleep Apnea with Cheyne-Stokes Breathing in Heart Failure – From Research to Clinical Practice and Beyond. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2018;1067:327-351. doi: 10.1007/5584_2018_146[↩]

- Cowie MR, Woehrle H, Wegscheider K, Vettorazzi E, Lezius S, Koenig W, Weidemann F, Smith G, Angermann C, d’Ortho MP, Erdmann E, Levy P, Simonds AK, Somers VK, Zannad F, Teschler H. Adaptive servo-ventilation for central sleep apnoea in systolic heart failure: results of the major substudy of SERVE-HF. Eur J Heart Fail. 2018 Mar;20(3):536-544. doi: 10.1002/ejhf.1048[↩]

- Iftikhar IH, Khayat RN. Central sleep apnea treatment in patients with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction: a network meta-analysis. Sleep Breath. 2022 Sep;26(3):1227-1235. doi: 10.1007/s11325-021-02512-y[↩]