Splenic infarction

Splenic infarction refers to occlusion of the splenic blood supply, leading to spleen tissue ischemia and eventual death of tissue (necrosis) 1. Splenic infarction may be the result of arterial or venous occlusion. Occlusion is usually caused by bland or septic emboli as well as venous congestion by abnormal cells. Splenic infarction may involve a small segmental area of the spleen or may be global depending on which vessel is occluded. This occurrence is caused by a wide variety of underlying disease states with prognosis dependent on the causative illness. The most typical presentation includes left sided abdominal pain in a patient with underlying hematologic disorder, blood borne malignancy, blunt abdominal trauma, hypercoagulable state or embolic illness. Treatment of splenic infarct ranges from supportive care to splenectomy 2.

Therapeutic splenic infarction via splenic embolization has been used to treat hemorrhage from traumatic splenic injuries. Splenic embolization has also been used in the treatment of severe portal hypertension and in the pre-operative phase of splenectomy to reduce intra-operative blood loss.

Splenic infarcts are considered a rare cause of abdominal pain although the exact prevalance is unclear. The diagnosis of splenic infarct is thought to be rising due to increased abdominal imaging, increased use of splenic embolization and increased nonoperative management of traumatic splenic injuries. Splenic infarction may affect patients of all ages. Patient 4o years of age and younger are more likey to have underlying hematologic illness while patients 40 years of age and older are more likely to suffer splenic infarct due to thromboembolic diseases 3.

Splenic infarct causes

There are numerous causes of splenic infarct. The two most common causes of splenic infarct (88% of splenic infarction) are thromboembolic disease that produce obstruction of larger vessels and infiltrative hematologic diseases that cause congestion of the splenic circulation by abnormal cells 4. In patients under 40 years of age, the most common cause is a hematologic disease 5. Causes of splenic infarction may be categorized as follows:

- Blood borne malignancy (leukemia, lymphoma), myelofibrosis

- Hypercoagulable states (sickle cell disease, protein C, and S, polycythemia vera, lupus anticoagulant, exogenous estrogen use, malignancy)

- Thromboembolic disorders (atrial fibrillation, endocarditis, patent foramen ovale, prosthetic heart valves, paradoxical emboli from right heart, left ventricular mural thrombus following myocardial infarct, infected thoracic aortic graft, HIV-associated mycobacterial infections)

- Blunt abdominal trauma

- Pancreatic disorders (pancreatitis, compressive pancreatic masses)

- Vascular disorders

- Autoimmune and collagen vascular diseases

- Trauma – torsion of the wandering spleen, left-heart catheterization via femoral artery approach, sclerotherapy of bleeding gastric varices, vasopressin infusion, embolization for splenic bleeding

- Operative causes – pancreatectomy, liver transplant 6

- Miscellaneous – splenic vein thrombosis, pancreatitis, amyloidosis, sarcoidosis, pancreatic cancer, acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), postpartum toxic shock syndrome

Additionally, the “wandering spleen,” have been noted in case reports of the splenic infarct.

Splenic infarct symptoms

The clinical presentation of splenic infarction ranges from asymptomatic infarction (discovered incidentally on radiologic or postmortem studies or at laparoscopy or laparotomy for another indication) to hemorrhagic shock (secondary to massive subcapsular hemorrhage with free rupture into the peritoneal cavity). Approximately one third of splenic infarcts are clinically occult.

Splenic infarction is a rare cause of left-upper-quadrant abdominal pain (up to 70%). Diagnosis is often suspected based on the presence of underlying disease states most likely to cause splenic infarction. A study published in 2010 set out to better characterize the modern experience of splenic infarction. This study performed chart reviews of 26 patients admitted to the hospital with diagnosis of splenic infarction. Their observations were as follows:

- Mean age 52 years old

- 50% complained of localized left sided abdominal pain

- 36% had left sided abdominal tenderness

- 32% splenomegaly

- 31% had no signs or symptoms localized to the spleen area

- 36% had fever temperature >100.4 °F (38 °C)

- 56% had white blood cell >12,000

- 71% had elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) level

- 32% had nausea and or vomiting

Interestingly, the authors noted that in 21 of 26 patients, the diagnosis of splenic infarct led to the diagnosis of a previously unrecognized underlying illness 1.

Splenic infarct diagnosis

Abdominal pain remains the leading chief complaint in patients diagnosed with a splenic infarct. Evaluation of patients who present with abdominal pain requires a broad differential approach 7, 8.

No specific diagnostic laboratory studies for splenic infarction exist. Lab evaluation my help rule in other causes of abdominal pain. Elevated liver function tests, bilirubin or lipase, may suggest a hepatobiliary or pancreatic source for pain. Elevated white blood cell count (leukocytosis) and elevated lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) may be found in splenic infarction. However, these results lack specificity to splenic infarct.

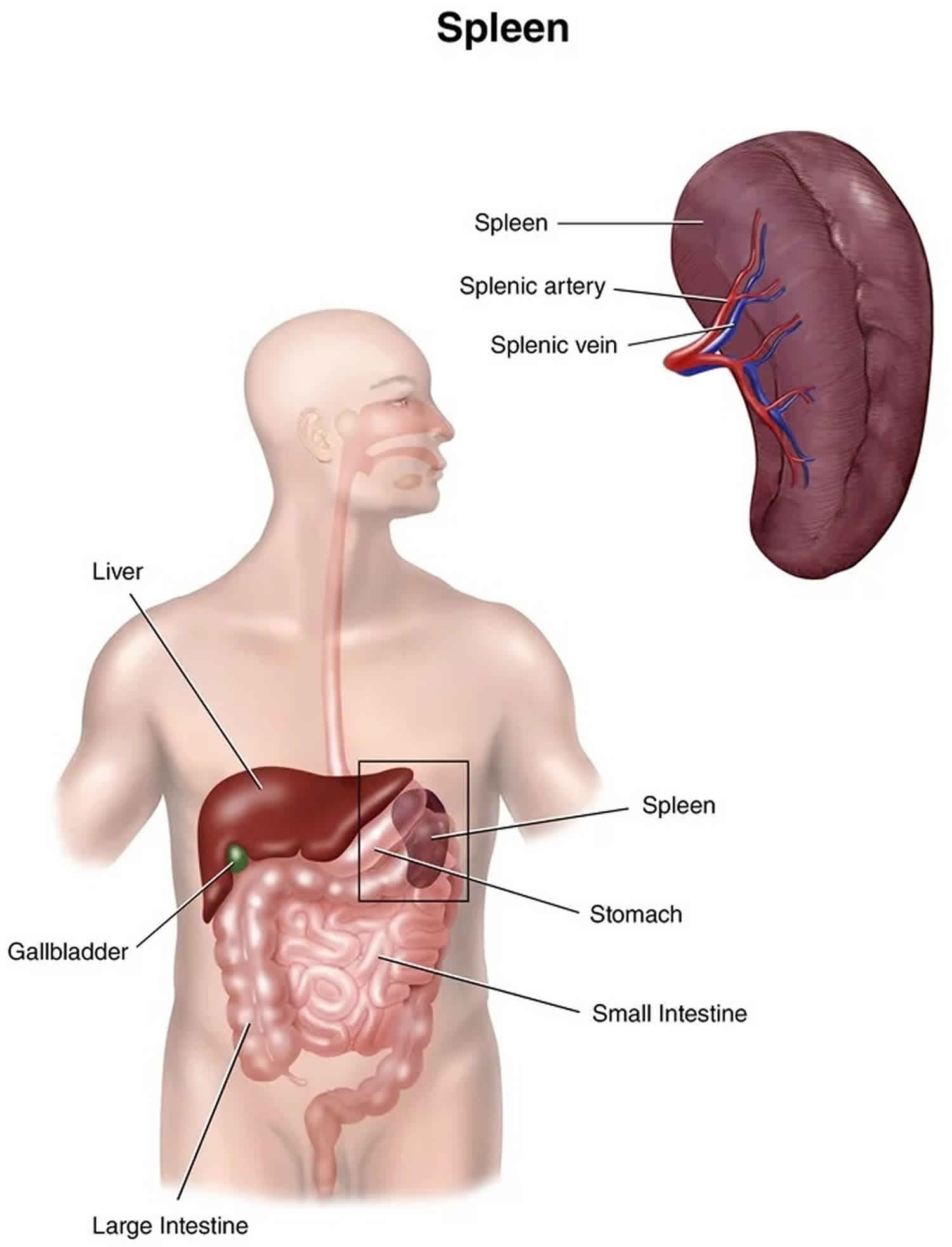

Radiographic testing is required to detect this rare illness. In the hyperacute phase of infarction, abdominal CT scan performed with intravenous contrast is the imaging modality of choice in suspected splenic infarction. Splenic infarct appears as a wedge-shaped area of splenic tissue with the apex pointed toward the helium and the base of the splenic capsule. As the infarction matures, the affected tissue may normalize, liquefy or become contracted or scarred. Abdominal ultrasound has also been used to detect splenic infarction. Ultrasound findings of the hypoechoic wedge-shaped region of splenic tissue indicate infarction. Evolution of infarction may appear as hyperechoic with retraction of the splenic capsule.

Splenic infarct treatment

Treatment of splenic infarct is based primarily on the underlying causative disease state. Splenic infarct in the non-infectious setting may be treated with analgesics, hydration, anti-emetics and other means of supportive care. Hospital admission may be required to provide supportive treatment, monitoring, and further diagnostic testing if the underlying cause is not established. In patients with sickle cell hemoglobinopathies, treatment to correct hypoxia and acidosis may be required. In the case of septic emboli, patients may require intravenous antibiotics and further cardiac evaluation. In patients with the underlying hematologic disease or autoimmune disease, consultation with hematology, oncology or rheumatology may be indicated. Abdominal pain due to uncomplicated cases of splenic infarction resolve without intervention in 7-14 days 9.

In the case of traumatic splenic injury, abnormal vasculature or hemodynamic instability, the surgical evaluation may be required. Dangerous complications of splenic infarct include pseudocyst formation, abscess, hemorrhage, splenic rupture, and aneurysm. In some instances, the infarcted splenic tissue may become infected and lead to abscess formation. Infarcted tissue may also undergo a hemorrhagic transformation. These complications warrant emergent surgical consultation.

In patients undergoing surgery, it is important to ensure that the patient does get vaccinated against encapsulated organisms with pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine.

Splenic infarct prognosis

The prognosis for splenic infarction varies according to the underlying disease process responsible for the infarct. For traumatic cases, the outlook is excellent but in patients with sickle cell disease or a chronic hematolgocial disorder, repeated episodes may occur 10. Splenectomies for infarction of massively enlarged spleens accompanying hematologic malignancies reportedly are associated with mortalities as high as 35%. At the other end of the spectrum, many infarcts are clinically occult, with no significant long-term complications.

Asplenic individuals have an increased lifetime risk for developing overwhelming postsplenectomy sepsis, with the highest rate in the pediatric age group. Patients should be counseled to seek medical attention even for seemingly minor infections, because these can progress to fatal bloodstream infection within hours.

These considerations have proved to be the impetus for splenic preservation.

- Chapman J, Kahwaji CI. Splenic Infarcts. [Updated 2019 May 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430902[↩][↩]

- Kato K, Gleeson TA. Splenic necrosis requiring ultrasound-guided drainage following meningococcal septicaemia. Oxf Med Case Reports. 2019 Mar;2019(3):omz020[↩]

- Smalls N, Obirieze A, Ehanire I. The impact of coagulopathy on traumatic splenic injuries. Am. J. Surg. 2015 Oct;210(4):724-9.[↩]

- Desai DC, Hebra A, Davidoff AM. Wandering spleen: a challenging diagnosis. South Med J. 1997 Apr. 90(4):439-43.[↩]

- Wand O, Tayer-Shifman OE, Khoury S, Hershko AY. A practical approach to infarction of the spleen as a rare manifestation of multiple common diseases. Ann. Med. 2018 Sep;50(6):494-500.[↩]

- Hayashi H, Beppu T, Okabe K, Masuda T, Okabe H, Baba H. Risk factors for complications after partial splenic embolization for liver cirrhosis. Br J Surg. 2008 Jun. 95 (6):744-50.[↩]

- Nofal R, Zeinali L, Sawaf H. Splenic infarction induced by epstein-barr virus infection in a patient with sickle cell trait. J Paediatr Child Health. 2019 Feb;55(2):249-251.[↩]

- el Barzouhi A, van Buren M, van Nieuwkoop C. Renal and Splenic Infarction in a Patient with Familial Hypercholesterolemia and Previous Cerebral Infarction. Am J Case Rep. 2018 Dec 10;19:1463-1466.[↩]

- Mamoun C, Houda F. [Splenic infarction revealing infectious endocarditis in a pregnant woman: about a case and brief literature review]. Pan Afr Med J. 2018;30:184.[↩]

- Fernando C, Mendis S, Upasena AP, Costa YJ, Williams HS, Moratuwagama D. Splenic Syndrome in a Young Man at High Altitude with Undetected Sickle Cell Trait. J Patient Exp. 2018 Jun;5(2):153-155.[↩]