What is squamous intraepithelial lesion

Squamous intraepithelial lesion is used to indicate that the cells collected from the cervical Pap smear may be precancerous. If the changes are low grade (low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion or LSIL), it means the size, shape and other characteristics of the cells suggest that if a precancerous lesion is present, it’s likely to be years away from becoming a cancer. If the changes are high grade (high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion or HSIL), the cells look severely abnormal and are less likely than the cells in LSIL to go away without treatment and there’s a greater chance that high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion may develop into cancer much sooner. Additional diagnostic testing is necessary.

The first step in finding cervical cancer is often an abnormal Pap test result. This will lead to further tests, which can diagnose cervical cancer.

Cervical cancer may also be suspected if you have symptoms like abnormal vaginal bleeding or pain during sex. Your primary doctor or gynecologist often can do the tests needed to diagnose pre-cancers and cancers and may also be able to treat a pre-cancer.

If there is a diagnosis of invasive cancer, your doctor should refer you to a gynecologic oncologist, a doctor who specializes in cancers of women’s reproductive systems.

Scientific studies have established human papillomavirus (HPV) as the major agent in the pathogenesis of cervical dysplasia and cancer of the cervix. HPV is a non-enveloped double-stranded DNA virus within the Papillomaviridae family. There are over 150 genotypes of HPV with 40 known to infect the anogenital tract. These 40 are divided into high-risk and low-risk groups based on evidence of their oncogenic potential. HPV16 and HPV18 are high-risk genotypes found in over 70% of HSILs and cervical squamous cell carcinomas. Opposed to low-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (LSIL), which represent transient HPV infections that are cleared within two to five years and have a low risk of malignancy, high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSILs) are associated with persistent infection and a greater risk of progression to invasive cancer, especially if the persistent infection is a high-risk genotype such as HPV16 and/or HPV 18 1.

The American Cancer Society recommends that women follow these guidelines to help find cervical cancer early. Following these guidelines can also find pre-cancers, which can be treated to keep cervical cancer from forming.

- All women should begin cervical cancer testing (screening) at age 21. Women aged 21 to 29, should have a Pap test every 3 years. HPV testing should not be used for screening in this age group (it may be used as a part of follow-up for an abnormal Pap test).

- Beginning at age 30, the preferred way to screen is with a Pap test combined with an HPV test every 5 years. This is called co-testing and should continue until age 65.

- Another reasonable option for women 30 to 65 is to get tested every 3 years with just the Pap test.

- Women who are at high risk of cervical cancer because of a suppressed immune system (for example from HIV infection, organ transplant, or long-term steroid use) or because they were exposed to DES in utero may need to be screened more often. They should follow the recommendations of their health care team.

- Women over 65 years of age who have had regular screening in the previous 10 years should stop cervical cancer screening as long as they haven’t had any serious pre-cancers (like CIN2 or CIN3) found in the last 20 years. Women with a history of CIN2 or CIN3 should continue to have testing for at least 20 years after the abnormality was found.

- Women who have had a total hysterectomy (removal of the uterus and cervix) should stop screening (such as Pap tests and HPV tests), unless the hysterectomy was done as a treatment for cervical pre-cancer (or cancer). Women who have had a hysterectomy without removal of the cervix (called a supra-cervical hysterectomy) should continue cervical cancer screening according to the guidelines above.

- Women of any age should NOT be screened every year by any screening method.

- Women who have been vaccinated against HPV should still follow these guidelines.

Some women believe that they can stop cervical cancer screening once they have stopped having children. This is not true. They should continue to follow American Cancer Society guidelines.

Although annual (every year) screening should not be done, women who have abnormal screening results may need to have a follow-up Pap test (sometimes with a HPV test) done in 6 months or a year.

The American Cancer Society guidelines for early detection of cervical cancer do not apply to women who have been diagnosed with cervical cancer, cervical pre-cancer, or HIV infection. These women should have follow-up testing and cervical cancer screening as recommended by their health care team.

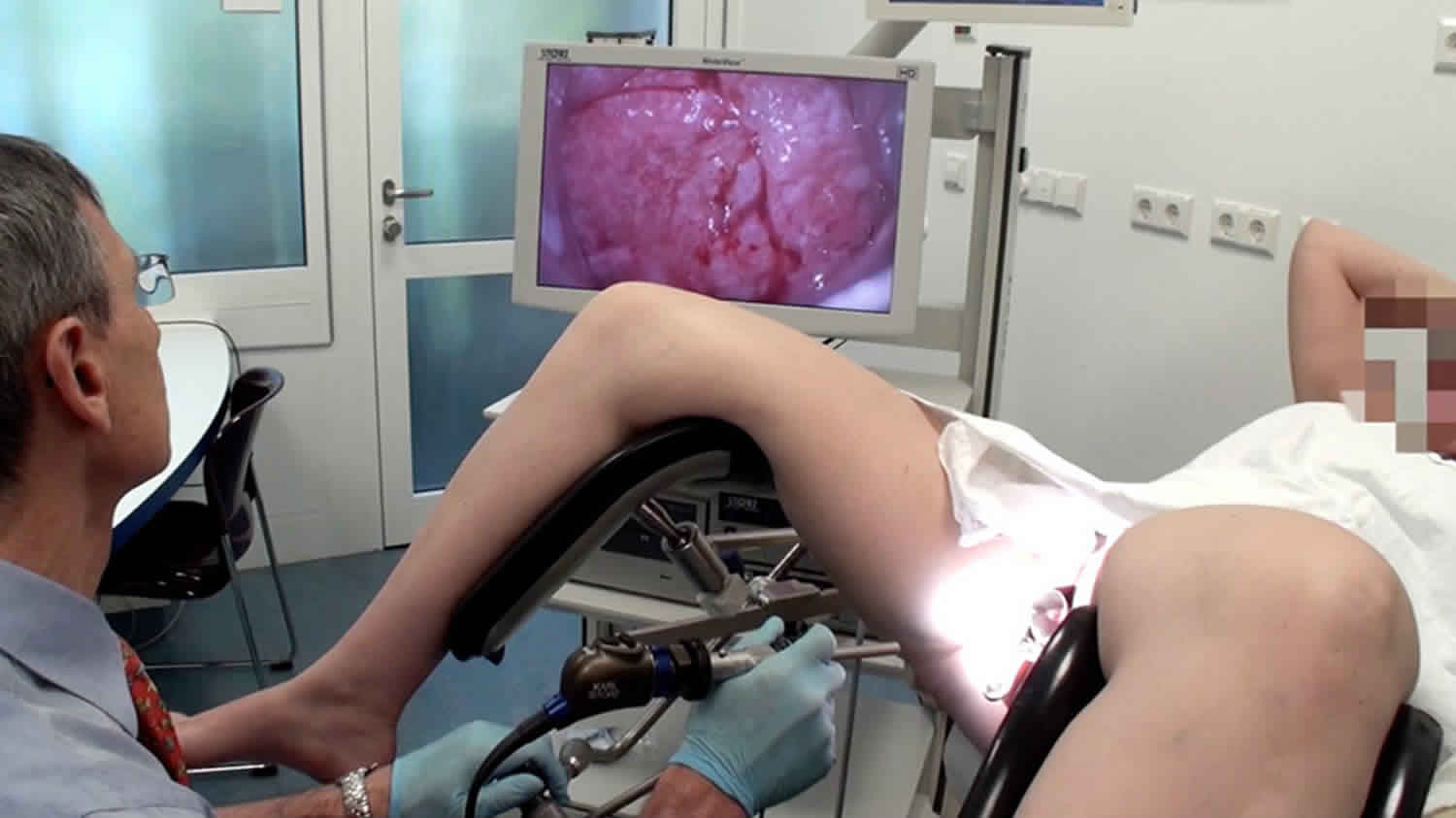

Figure 1. Squamous intraepithelial lesion

Abbreviations: Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion or LSIL; high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion or HSIL

Tests for women with symptoms of cervical cancer or abnormal Pap test results

Medical history and physical exam

First, the doctor will ask you about your personal and family medical history. This includes information related to risk factors and symptoms of cervical cancer. A complete physical exam will help evaluate your general state of health. The doctor will do a pelvic exam and may do a Pap test if one has not already been done. In addition, your lymph nodes will be felt for evidence of metastasis (cancer spread).

The Pap test is a screening test, not a diagnostic test. It cannot tell for certain if you have cervical cancer. An abnormal Pap test result may mean more testing, sometimes including tests to see if a cancer or a pre-cancer is actually present. The tests that are used include colposcopy (with biopsy), endocervical scraping and cone biopsies.

Colposcopy

If you have certain symptoms that are worrisome for cancer or if your Pap test shows abnormal cells, you will need to have a test called colposcopy. You will lie on the exam table as you do with a pelvic exam. A speculum will be placed in the vagina to help the doctor see the cervix. The doctor will use a colposcope to examine the cervix. The colposcope is an instrument that stays outside the body and has magnifying lenses. It lets the doctor see the surface of the cervix closely and clearly. Colposcopy itself usually causes no more discomfort than any other speculum exam. It can be done safely even if you are pregnant. Like the Pap test, it is better not to have it during your menstrual period.

At the time of the procedure, the doctor will apply a weak solution of acetic acid (similar to vinegar) to your cervix to make any abnormal areas easier to see. If an abnormal area is seen, a biopsy (removal of a small piece of tissue) will be done. The tissue is sent to a lab to be looked at under a microscope. A biopsy is the best way to tell for certain whether an abnormal area is a pre-cancer, a true cancer, or neither. Although the colposcopy procedure is usually not painful, the cervical biopsy can cause discomfort, cramping, bleeding, or even pain in some women.

Cervical biopsies

Several types of biopsies can be used to diagnose cervical pre-cancers and cancers. After these procedures, patients may feel mild cramping or pain and may also have some light bleeding.

Colposcopic biopsy

For this type of biopsy, the cervix is examined with a colposcope to find the abnormal areas. A local anesthetic may then be used to numb the cervix before the biopsy. Using biopsy forceps, a small section of the abnormal area is removed.

Endocervical curettage (endocervical scraping)

Sometimes the transformation zone (the area at risk for HPV infection and pre-cancer) cannot be seen with the colposcope, so something else must be done to check that area for cancer. This means taking a scraping of the endocervix by inserting a narrow instrument (called a curette) into the endocervical canal (the part of the cervix closest to the uterus). The curette is used to scrape the inside of the canal to remove some of the tissue, which is then sent to the lab for examination.

Cone biopsy

In this procedure, also known as conization, the doctor removes a cone-shaped piece of tissue from the cervix. The tissue removed in the cone includes the transformation zone where cervical pre-cancers and cancers are most likely to start.

A cone biopsy is not only used to diagnose pre-cancers and cancers. It can also be used as a treatment since it can sometimes completely remove pre-cancers and some very early cancers.

The methods commonly used for cone biopsies are the loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), also called the large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ), and the cold knife cone biopsy. With both procedures, you might have mild cramping and some bleeding for a few weeks.

- Loop electrosurgical procedure (LEEP or LLETZ): In this method, the tissue is removed with a thin wire loop that is heated by electricity and acts as a small knife. For this procedure, a local anesthetic is used, and it can be done in your doctor’s office.

- Cold knife cone biopsy: This method uses a surgical scalpel or a laser instead of a heated wire to remove tissue. · You will receive anesthesia during the operation (either a general anesthesia, where you are asleep, or a spinal or epidural anesthesia, where an injection into the area around the spinal cord makes you numb below the waist) and it is done in a hospital.

Having any type of cone biopsy will not prevent most women from getting pregnant, but if a large amount of tissue has been removed, women may have a higher risk of giving birth prematurely.

Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), classically referred to as cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 1 (CIN 1) or mild dysplasia. Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) usually represents reversible infection with human papillomavirus (HPV). Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL) doesn’t normally need treatment as the cell changes often return to normal over time (usually resolves spontaneously within 9-12 months). There are numerous follow-up studies of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grades 1 (CIN 1) showing a highly variable risk of progression to CIN 2-3 and a consequent risk of invasive cancer in a small minority of patients 2.

A large retrospective follow-up study of mild, moderate and severe dysplasia by Holowaty et al. 3 showed that the majority of cases of mild (62.2%) and moderate dysplasia (53.7%) regressed (two negative smears within 2 years) while progression to moderate dysplasia or worse was approximately 25% within 5 years, which is consistent with other studies.

Likelihood of progression depends on persistence of HPV, its integration into the host genome and its type 4:

- HPV16 and 33 have the highest risk of progression to CIN3.

- HPV16 and 31 to have the least likelihood of regression.

Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion symptoms

Women with early cervical cancers and low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion usually have no symptoms. Symptoms often do not begin until the cervical cancer becomes invasive and grows into nearby tissue. When this happens, the most common symptoms are:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding, such as bleeding after vaginal sex, bleeding after menopause, bleeding and spotting between periods, and having (menstrual) periods that are longer or heavier than usual. Bleeding after douching or after a pelvic exam may also occur.

- An unusual discharge from the vagina − the discharge may contain some blood and may occur between your periods or after menopause.

- Pain during sex.

These signs and symptoms can also be caused by conditions other than cervical cancer. For example, an infection can cause pain or bleeding. Still, if you have any of these symptoms, see a health care professional right away. Ignoring symptoms may allow the cancer to grow to a more advanced stage and lower your chance for effective treatment.

Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion treatment

Low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (LSIL), classically referred to as CIN1 or mild dysplasia, does not require treatment and should be followed conservatively 5. Patients with LSIL should return in one year for co-testing, This involves a repeat Pap smear with HPV molecular testing as the majority of the lesions will regress on their own.

High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion

High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL) is a squamous cell abnormality associated with human papillomavirus (HPV) 1. High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL) encompasses the previously used terms of cervical intraepithelial neoplasia-2 (CIN 2), cervical intraepithelial neoplasia-3 (CIN 3), moderate and severe dysplasia and carcinoma in situ. This current terminology for high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion was introduced by the Bethesda System for Reporting Cervical Cytology for cytology specimens in 1988, and has since been adopted for histology specimens by the Lower Anogenital Squamous Terminology Standardization Consensus Conference and the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2012 and 2014, respectively. Though not all high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL) will progress to cancer, it is considered a pre-cancerous lesion and therefore is usually treated aggressively. Though high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion can involve various cutaneous and mucosal sites within the anogenital tract, this post will focus on cervical high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion.

Women with biopsy-proven high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL) will likely have a history of multiple risk factors associated with HPV infection, a positive HPV test and/or a history of abnormal pap tests. Abnormal colposcopic findings characteristic of high-grade changes include dense acetowhite epithelium, rapid appearance of acetowhitening, cuffed crypt openings, coarse mosaic, coarse punctuation, a sharp border, an inner border sign and a ridge sign. The inner border sign is when there is a sharply demarcated acetowhite area within a less opaque acetowhite area. The ridge sign is the presence of thick ledges of opaque acetowhite epithelium growing irregularly within the squamocolumnar junction.

Since high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HGSIL) is caused by HPV infection, it is found more commonly in women with specific genetic and behavioral factors which increase their risk of acquiring HPV. HPV prevalence is highest in young, sexually active females, then progressively drops until menopause, with some studies showing a slight increase after menopause. This decline in middle-age is thought to be the result of an effective immune response after exposure to HPVs, in addition to the likelihood of less exposure to the HPV virus. An immunocompromised state, such as after transplant therapy and HIV-infected individuals, increases a patient’s risk of persistent infection and development of a squamous intraepithelial lesion. Studies indicate a younger age of sexual intercourse and the number of sexual partners increases the risk of HPV infection as well as more recent sexual activity. Male partner promiscuity is also a factor as well as condom use and circumcision, as both significantly reduce the risk of HPV infection. Women who have sex with women also have an increased risk of cervical neoplasia. Multiparous women, specifically greater than 7, are also at increased risk. There is a strong association between smoking and cervical neoplasia, independent of HPV status, presumably due to the presence of carcinogens within the cervical mucus. Certain HLA class II haplotypes, notably HLA B*07+HLA-DQB1*302, have a positive association with SILs and invasive cancer with evidence suggesting that the haplotype may influence HPV antigen presentation and immune response. Other HLA class II haplotypes have been found to be protective. Oral contraceptive use may somewhat increase a patient’s risk of cervical neoplasia, though studies have not been consistent.

High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion symptoms

Women with early cervical cancers and high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion usually have no symptoms. Symptoms often do not begin until the cervical cancer becomes invasive and grows into nearby tissue. When this happens, the most common symptoms are:

- Abnormal vaginal bleeding, such as bleeding after vaginal sex, bleeding after menopause, bleeding and spotting between periods, and having (menstrual) periods that are longer or heavier than usual. Bleeding after douching or after a pelvic exam may also occur.

- An unusual discharge from the vagina − the discharge may contain some blood and may occur between your periods or after menopause.

- Pain during sex.

These signs and symptoms can also be caused by conditions other than cervical cancer. For example, an infection can cause pain or bleeding. Still, if you have any of these symptoms, see a health care professional right away. Ignoring symptoms may allow the cancer to grow to a more advanced stage and lower your chance for effective treatment.

High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion diagnosis

The current American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommendations for cervical carcinoma screening in women is dependent upon age, HIV infection/immunodeficiency and pregnancy status. Screening should be initiated at 21 years of age. Women ages 21 to 29 should be screened by cytology every three years. Women ages 30 to 65 should be screened with cytology and HPV co-testing every five years or by cytology alone every three years. Depending on the HPV test used, the test will provide pooled results for high-risk HPV subtypes and/or individual genotype results for HPV16 and 18. The risk of high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion in a patient with a positive HPV test and an abnormal pap test is approximately 20% and increases to 33% if HPV positive at more than one visit.

A Papanicolaou (Pap) test is the preferred initial method of screening for cervical neoplasia. This is performed by opening the vaginal canal with a speculum, fully visualizing the cervix, using a cervical broom or spatula to exfoliate cells from the transformation zone and transferring the cells either into liquid preservative (liquid-based cytology) or directly onto a microscope slide (conventional cytology). Pathology will process the specimens according to the type of test they receive.

Diagnosis of high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion on cytology requires specific criteria to be met. The cells are smaller with less cytoplasmic maturity than that of LGSIL. Occasionally, the cytoplasm may be densely keratinized. high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cells occur singly as well as in sheets or syncytial aggregates. Though the size of the nucleus itself is variable, the cells must have a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. The nuclei are often hyperchromatic but can be normo- to hyperchromatic. The chromatin can range from evenly distributed and fine to coarsely granular. Nuclear contours must be distinctly irregular with prominent indentations and/or grooves. Nucleoli are usually not a feature of high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, though may be seen when high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion involves the endocervical glands.

The American Society for Colposcopy and Cervical Pathology publishes guidelines for the management of woman based on their Pap test and HPV test results. For women ages 21-24, colposcopy is recommended following an high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cytology diagnosis. Women over the age of 24 years old should also have colposcopy performed, though management with an excisional procedure is acceptable. Around 60% of women with high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cytology will have at least CIN 2 on biopsy, with approximately 2% showing invasive cancer, though the latter is more likely in older women. Women over 30 years of age have an 8% 5-year risk of cervical cancer after a diagnosis of high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. Biopsies taken during colposcopy are examined by histology. Histologic criteria for high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion exceeds the extent and degree of nuclear atypia allowed for a diagnosis of low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion and includes less maturation, a higher nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio, decreased organization from the lower immature cell layers to the superficial mature layers (loss of polarity), a greater degree of nuclear pleomorphism, highly irregular nuclear contours, increased mitotic index and abnormal mitotic figures, especially within more superficial layers of the epithelium. CIN3 must have full thickness atypia. When faced with not-so-straight-forward biopsies where the pathologist is debating between benign mimics of high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, such as immature metaplasia or atypical atrophy, utilizing the biomarker p16 may help distinguish them, as p16 shows intense and continuous staining in high grade squamous intraepithelial lesions and suggests infection with a high-risk HPV type.

High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion treatment

High grade squamous intraepithelial lesion, classically referred to as CIN2/3 or CIS (carcinoma in situ) usually requires an excisional procedure for treatment. Ablative procedures can be offered, but the majority of clinicians perform excisional procedures to give the pathologist a better specimen to evaluate. Excisional procedures provide assurance that an underlying cancer is identified and adequate treatment for the lesion is provided. A loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) to remove the abnormal tissue with a thin electrified wire that cuts the specimen from the cervix can be performed in the office. A cold knife cone (CKC) typically is performed in the operating room, using a knife to resect a cone shaped portion of cervical tissue. The advantage of a cold knife cone is that the pathologist can identify the margins more clearly and because they are not obscured by the burn artifact created with the electrified wire. Following a complete excision and negative margins, patients require yearly follow-up with a pap smear. If underlying cancer is discovered, treatment plans are expanded, and an oncologist is consulted. If an excisional procedure provides results in positive LEEP (loop electrosurgical excision procedure) margin findings, the decision to re-excise or follow conservatively is based on the patient’s age and fertility status.

Women ages 21-24 with high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cytology are recommended to undergo colposcopy. If cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN 2) or greater is not diagnosed on biopsy, it is recommended the patient follow-up with cytology and colposcopy every six months for a 24 month period, as long as her exams are adequate and reveal no squamous intraepithelial lesions or at most low grade squamous intraepithelial lesion. If high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cytology or a high-grade colposcopic lesion is found during this time, a biopsy should be taken. In patients where high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cytology persists for 24 months, but no high-grade lesion is identified on biopsy, a diagnostic excisional procedure is recommended. If colposcopy is inadequate, CIN3 is specified on biopsy, or cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN 2) or CIN2-3 persists for 24 months, then a diagnostic excisional procedure is recommended. If cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN 2) is specified on biopsy, observation for 12 months using both cytology and colposcopy every six months is recommended. This is because cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 2 (CIN 2) has a higher regression rate and less risk of progression to cancer than cervical intraepithelial neoplasia grade 3 (CIN 3), especially in younger women. Once the patient has two consecutive negative results on cytology and no evidence of a colposcopic abnormality, a co-test is recommended a year later. If negative, a second co-test is recommended after three years. If either co-test is abnormal, colposcopy is recommended.

Pregnant women found to have high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion cytology should not undergo excisional treatment; only colposcopy is acceptable. If a histologic diagnosis of a high-grade lesion is made, she may have additional cytologic and colposcopic exams up to every 12 weeks. If cytology results are suggestive of invasive cancer or if the colposcopic appearance of the lesions worsens, a repeat biopsy is recommended. It is also considered acceptable to defer re-evaluation until the patient is at least six weeks postpartum. A diagnostic excisional procedure is only recommended if there is a concern for invasive cancer.

For women >24 years old without special circumstances and with a high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion Pap test result, either immediate excisional procedure or colposcopy is recommended, regardless of HPV results at co-testing. If the colposcopic exam is inadequate, a diagnostic excisional procedure is recommended. If the colposcopy is adequate and high grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (CIN2, CIN3 or CIN2-3) is confirmed on biopsy, ablation of the transformation zone or excision is considered acceptable. However, only a diagnostic excisional procedure is acceptable if the colposcopy is inadequate or the endocervical curettage shows a high-grade lesion.

Once the patient is treated, regardless of age, her recommended follow-up is HPV co-testing at 12 and 24 months post-treatment. If both are negative, she can be retested in 3 years. If this test is negative, she can return to routine screening for at least the next 20 years. An abnormal test should result in colposcopy with endocervical sampling.

Table 1. Comparison of the characteristics of treatment methods for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia

| Method | Procedure | Strengths | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cryotherapy | A highly cooled metal disc is applied to the cervix for the purpose of freezing and therefore destroying precancerous lesions, with subsequent regeneration to normal epithelium. |

|

|

| Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) | Abnormal areas are removed from the cervix using a loop made of thin wire powered by an electrosurgical unit. |

|

|

| Cold knife conization (CKC) | A cone-shaped area is removed from the cervix, including portions of the outer and inner cervix. |

|

|

Cryotherapy

Cryotherapy eliminates precancerous areas on the cervix by freezing (an ablative method) 6. It involves applying a highly cooled metal disc (cryoprobe) to the cervix and freezing the abnormal areas (along with normal areas) covered by it (see Figure 2). The supercooling of the cryoprobe is accomplished using a tank with compressed carbon dioxide (CO2) or nitrous oxide (N2O) gas. Cryotherapy can be performed at all levels of the health system, by health-care providers (doctors, nurses and midwives) who are skilled in pelvic examination and trained in cryotherapy. It takes about 15 minutes and is generally well tolerated and associated with only mild discomfort. It can, therefore, be performed without anaesthesia. Following cryotherapy, the frozen area regenerates to normal epithelium.

Eligibility criteria: Screen-positive women or women with histologically confirmed CIN2+ are eligible for cryotherapy if the entire lesion and squamocolumnar junction are visible, and the lesion does not cover more than three quarters of the ectocervix. If the lesion extends beyond the cryoprobe being used, or into the endocervical canal, the patient is not eligible for cryotherapy. The patient is not eligible for cryotherapy if the lesion is suspicious for invasive cancer.

Post procedure: It takes a month for the cervical tissue to regenerate. The patient should be advised that during this time she may have a profuse, watery discharge and she should avoid sexual intercourse until all discharge stops, or use a condom if intercourse cannot be avoided.

Figure 2. Cryotherapy for squamous intraepithelial lesion (cervical intraepithelial neoplasia)

[Source 6 ]Loop electrosurgical excision procedure

Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) is also called large loop excision of the transformation zone (LLETZ) or loop diathermy, is the removal of abnormal areas from the cervix using a loop made of thin wire powered by an electrosurgical unit. The loop tool cuts and coagulates at the same time, and this is followed by use of a ball electrode to complete the coagulation (see Figure 3). Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) is the most common treatment for abnormal cervical cells. Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) aims to remove the lesion and the entire transformation zone. The tissue removed can be sent for examination to the histopathology laboratory, allowing the extent of the lesion to be assessed. Thus, loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) serves a double purpose: it removes the lesion (thus treating the pre-cancer) and it also produces a specimen for pathological examination. The procedure can be performed under local anaesthesia on an outpatient basis and usually takes less than 30 minutes. However, following loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP), a patient should stay at the outpatient facility for a few hours to assure bleeding does not occur.

Loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) is a relatively simple surgical procedure, but it should only be performed by a trained health-care provider with demonstrated competence in the procedure and in recognizing and managing intraoperative and postoperative complications, such as haemorrhage; e.g. a gynaecologist. LEEP is best carried out in facilities where back-up is available for management of potential problems; in most cases, this will limit LEEP to at least the secondary-level facilities (i.e. district hospitals).

Eligibility criteria: Screen-positive women or women with histologically confirmed CIN2+ are eligible for LEEP if the lesion is not suspicious for invasive cancer.

Post procedure: The patient should be advised to expect mild cramping for a few days and some vaginal discharge for up to one month. Initially, this can be bloody discharge for 7–10 days, and then it can transition to yellowish discharge. It takes one month for the tissue to regenerate, and during this time the patient should avoid sexual intercourse or use a condom if intercourse cannot be avoided.

Figure 3. LEEP cone biopsy

Cold knife conization

Cold knife conization is the removal of a cone-shaped area from the cervix, including portions of the outer (ectocervix) and inner cervix (endocervix) (see Figure 4). The amount of tissue removed will depend on the size of the lesion and the likelihood of finding invasive cancer. The tissue removed is sent to the pathology laboratory for histopathological diagnosis and to ensure that the abnormal tissue has been completely removed. A cold knife conization is usually done in a hospital, with the necessary infrastructure, equipment, supplies and trained providers. It should be performed only by health-care providers with surgical skill – such as gynaecologists or surgeons trained to perform the procedure – and competence in recognizing and managing complications, such as bleeding. The procedure takes less than one hour and is performed under general or regional (spinal or epidural) anesthesia. The patient may be discharged from hospital the same or the next day.

Eligibility criteria: Cold knife conization should be reserved for cases that cannot be resolved with cryotherapy or LEEP. It should be considered in the presence of glandular pre-cancer or microinvasive cancer lesions of the cervix.

Post procedure: Following cold knife conization, patients may have mild cramping for a few days and a bloody vaginal discharge, transitioning into a yellow discharge for 7–14 days. It takes 4–6 weeks for the cervix to heal (depending on the extent of the procedure) and during this time the patient should avoid sexual intercourse or use a condom if intercourse cannot be avoided.

Figure 4. Cold knife conization

Treatment Possible complications

All three treatment modalities may have similar complications in the days following the procedure. All of these complications may be indications of continuing bleeding from the cervix or vagina or an infection that needs to be treated.

Patients should be advised that if they have any of the following symptoms after cryotherapy, LEEP or cold knife conization, they should seek care at the closest facility without delay:

- bleeding (more than menstrual flow)

- abdominal pain

- foul-smelling discharge

- fever.

Follow-up after treatment

A follow-up visit including cervical cancer screening is recommended 12 months after treatment to evaluate the woman post-treatment and detect recurrence. If this follow-up rescreen is negative, the woman can be referred back to the routine screening programme.

An exception is if the patient has a histopathological result at the time of treatment that indicates CIN3 or adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) based on a specimen from LEEP or cold knife conization. In this case, rescreening is recommended every year for three years. If these rescreens are negative, she is then referred back to the routine screening programme.

If the patient treated for pre-cancer has a positive screen on her follow-up visit (indicating persistence or recurrence of cervical pre-cancer), retreatment is needed. If the initial treatment was with cryotherapy, then retreatment should be performed using LEEP or cold knife conization, if feasible.

If a histopathological result from a specimen obtained from a punch biopsy, LEEP or cold knife conization procedure indicates cancer, it is critical that the patient be contacted and advised that she must be seen at a tertiary care hospital as soon as possible.

- Khieu M, Butler SL. Cancer, Squamous Cell, High Grade Squamous Intraepithelial Lesion (HGSIL) [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430728[↩][↩]

- Bansal N, Wright JD, Cohen CJ, Herzog TJ (2008). Natural history of established low-grade cervical intraepithelial (CIN1) lesions. Anticancer Res 28:1763-6.[↩]

- Holowaty P, Miller AB, Rohan T, To T (1999). Natural history of dysplasia of the uterine cervix. J Natl Cancer Inst 91:252-8.[↩]

- Jaisamrarn U, Castellsague X, Garland SM et al. (2013). Natural history of HPV infection to cervical lesion or clearance: analysis of the control arm of the large, randomised PATRICIA study. PLoS One 8:e79260.[↩]

- Cooper DB, McCathran CE. Cervical, Dysplasia. [Updated 2018 Oct 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2018 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK430859[↩]

- Comprehensive Cervical Cancer Control: A Guide to Essential Practice. 2nd edition. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2014. 5, Screening and treatment of cervical pre-cancer. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK269601[↩][↩][↩]