Tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is a disease caused by bacteria called Mycobacterium tuberculosis. The bacteria usually attack the lungs, but tuberculosis bacteria can also attack any part of the body such as the kidney, spine, and brain. Not everyone infected with TB bacteria becomes sick. As a result, two TB-related conditions exist: latent TB infection and tuberculosis disease. Tuberculosis is a treatable and curable disease. If it is not treated properly, TB can progress and even be fatal.

It is important to understand that there is a difference between being infected with TB (latent TB) and having active TB disease. Someone who is infected with TB has the TB bacteria in their body. The body’s immune system is protecting them from the germs and they are not sick. This is referred to as latent TB.

Someone with tuberculosis disease is sick and can spread the disease to other people. A person with TB disease needs to see a doctor as soon as possible. This is referred to as active tuberculosis.

There are also forms of tuberculosis that are multi-drug resistant or even worse extremely multi-drug resistant tuberculosis. This means that some of the drugs used to treat the infection are not effective against the resistant TB bacteria in the body.

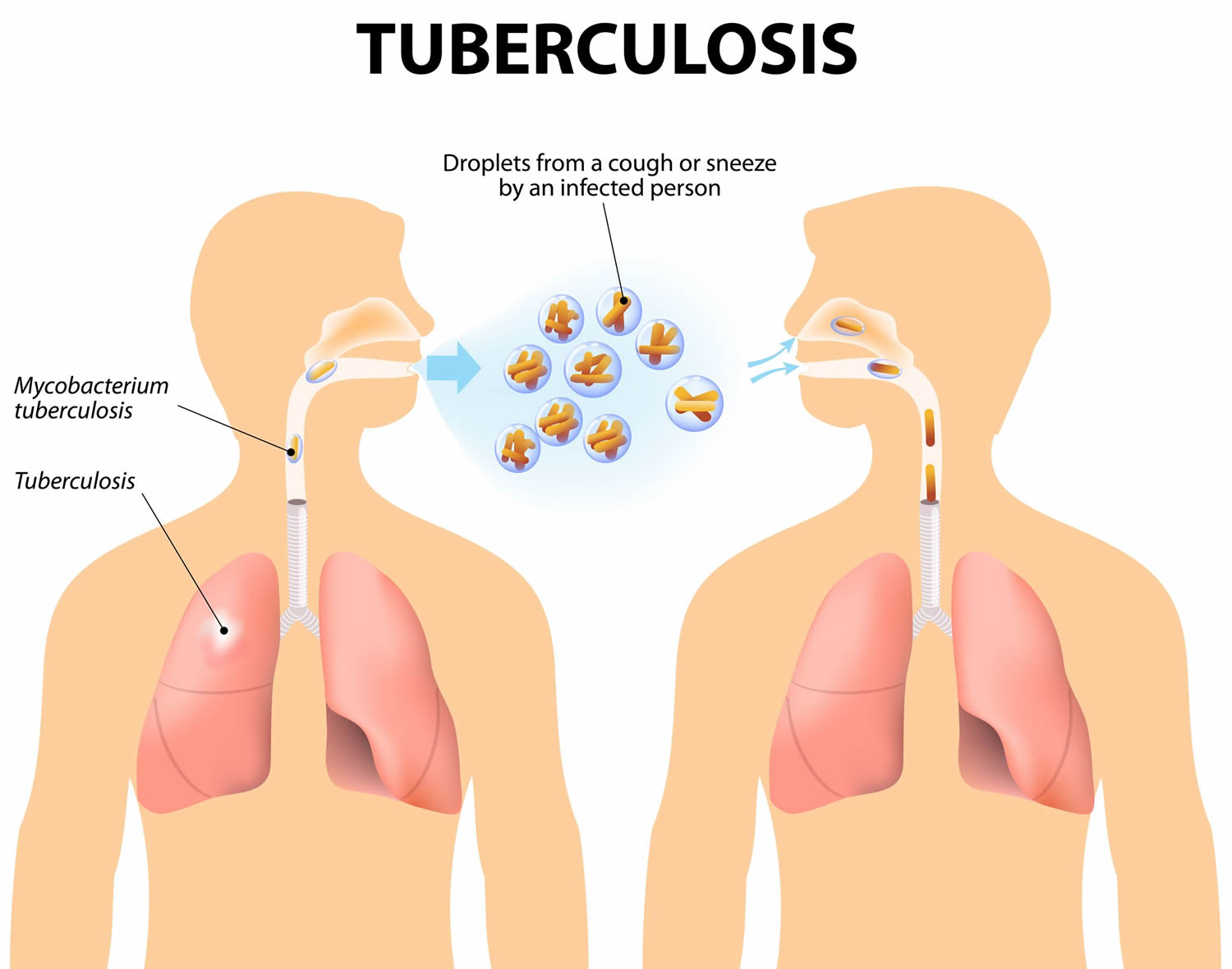

Tuberculosis spreads through the air when a person with tuberculosis of the lungs or throat coughs, sneezes, or talks. If you have been exposed, you should go to your doctor for tests. You are more likely to get TB if you have a weak immune system.

People with weakened immune systems (those with HIV/AIDS, those receiving chemotherapy, or children under 5 years old, for example) are at a greater risk for developing tuberculosis disease. When they breathe in tuberculosis bacteria, the bacteria settle in their lungs and start growing because their immune systems cannot fight the bacteria. In these people, tuberculosis disease may develop within days or weeks after the infection.

In other people who are healthy at the time of they are infected with latent tuberculosis, active tuberculosis disease may not develop until months or years later, at a time when the immune system becomes weak for other reasons and they are no longer able to fight the germs (Mycobacteria).

When a person gets active tuberculosis disease, it means tuberculosis bacteria are multiplying and attacking the lung(s) or other parts of the body, such as the lymph nodes, bones, kidney, brain, spine, and even the skin. From the lungs, tuberculosis bacteria move through the blood or lymphatic system to different parts of the body. Symptoms of active disease include cough, loss of weight and appetite, fever, chills and night sweats as well as symptoms related to the function of a specific organ or system that is affected; for example, coughing up blood or sputum in tuberculosis of the lungs, or bone pain if the bacteria have invaded the bones.

Symptoms of tuberculosis in the lungs may include:

- A bad cough that lasts 3 weeks or longer

- Weight loss

- Loss of appetite

- Coughing up blood or mucus

- Weakness or fatigue

- Fever

- Night sweats

Skin tests, blood tests, x-rays, and other tests can tell if you have tuberculosis. If not treated properly, tuberculosis can be deadly. You can usually cure active TB by taking several medicines for a long period of time.

Tuberculosis is present globally. About 1.4 billion people, or one-quarter of the world’s population, are infected with tuberculosis. Most infected people have latent tuberculosis, meaning they have the tuberculosis germs in their bodies, but their immune systems protect them from becoming sick. However, about 10 million people have active tuberculosis disease, worldwide. The bulk of the global burden of new infection and tuberculosis death is borne by developing countries with 6 countries, India, Indonesia, China, Nigeria, Pakistan, and South Africa, accounting for 60% of TB death in 2015 1. In 2017, 10 million people fell ill with tuberculosis, and 1.6 million died from the disease (including 0.3 million among people with HIV). Developing countries account for a disproportionate share of tuberculosis disease burden. In addition to the six countries, several countries in Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, and Latin and Central America continue to have an unacceptably high burden of tuberculosis 2. In the United States, tuberculosis is much less common, however, it continues to cause disproportionate illness in certain populations.

In more advanced countries, high burden tuberculosis is seen among recent arrivals from tuberculosis-endemic zones, health care workers, and HIV-positive individuals. Use of immunosuppressive agents such as long-term corticosteroid therapy has also been associated with an increased risk.

Tuberculosis key points

- It is not easy to become infected with tuberculosis.

- Most infected people have latent tuberculosis, meaning they have the tuberculosis germs in their bodies, but their immune system protects them from becoming sick and they are not contagious.

- Tuberculosis can almost always be treated and cured if you take medicine as directed.

- There are forms of tuberculosis that are drug resistant.

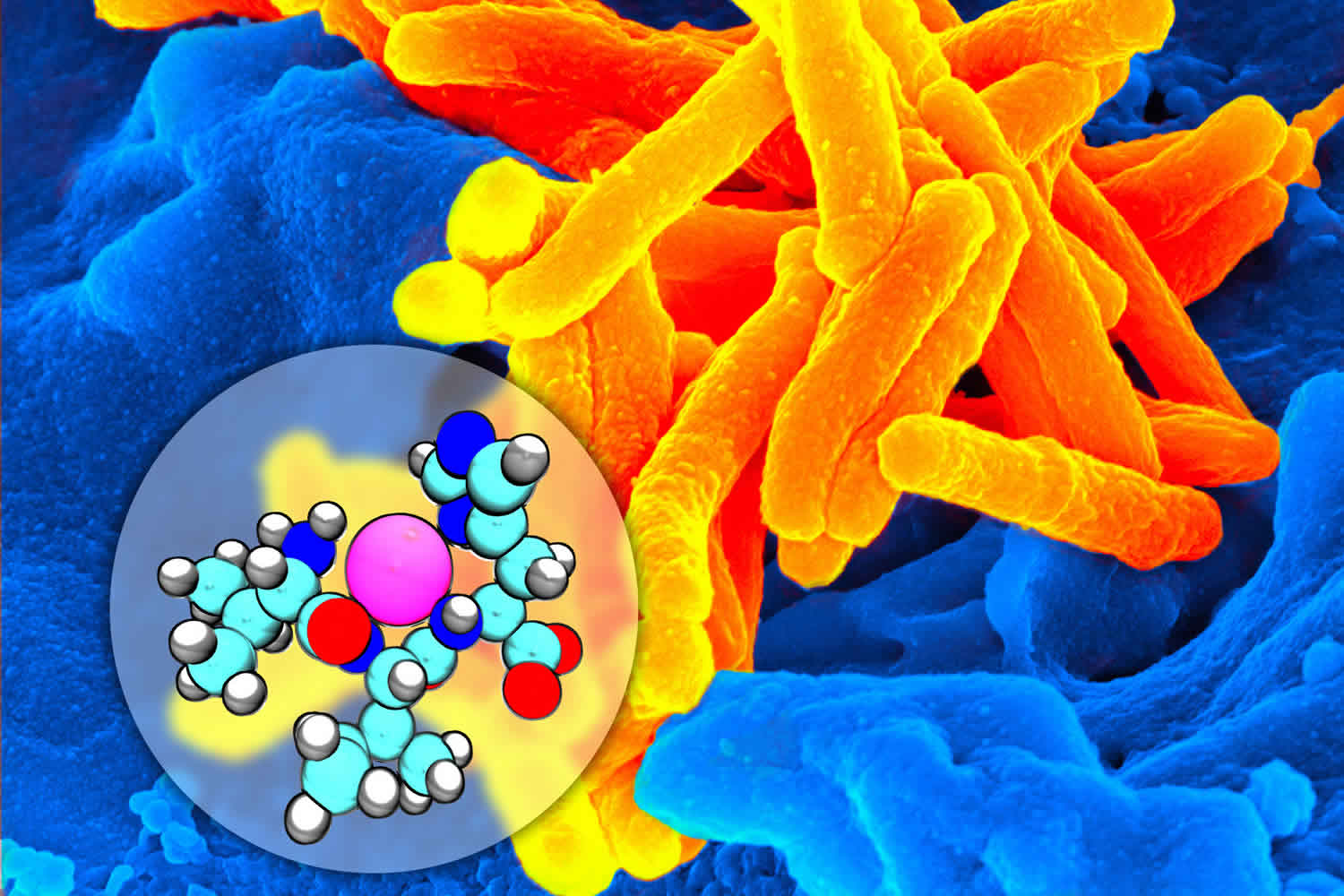

Figure 1. Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria

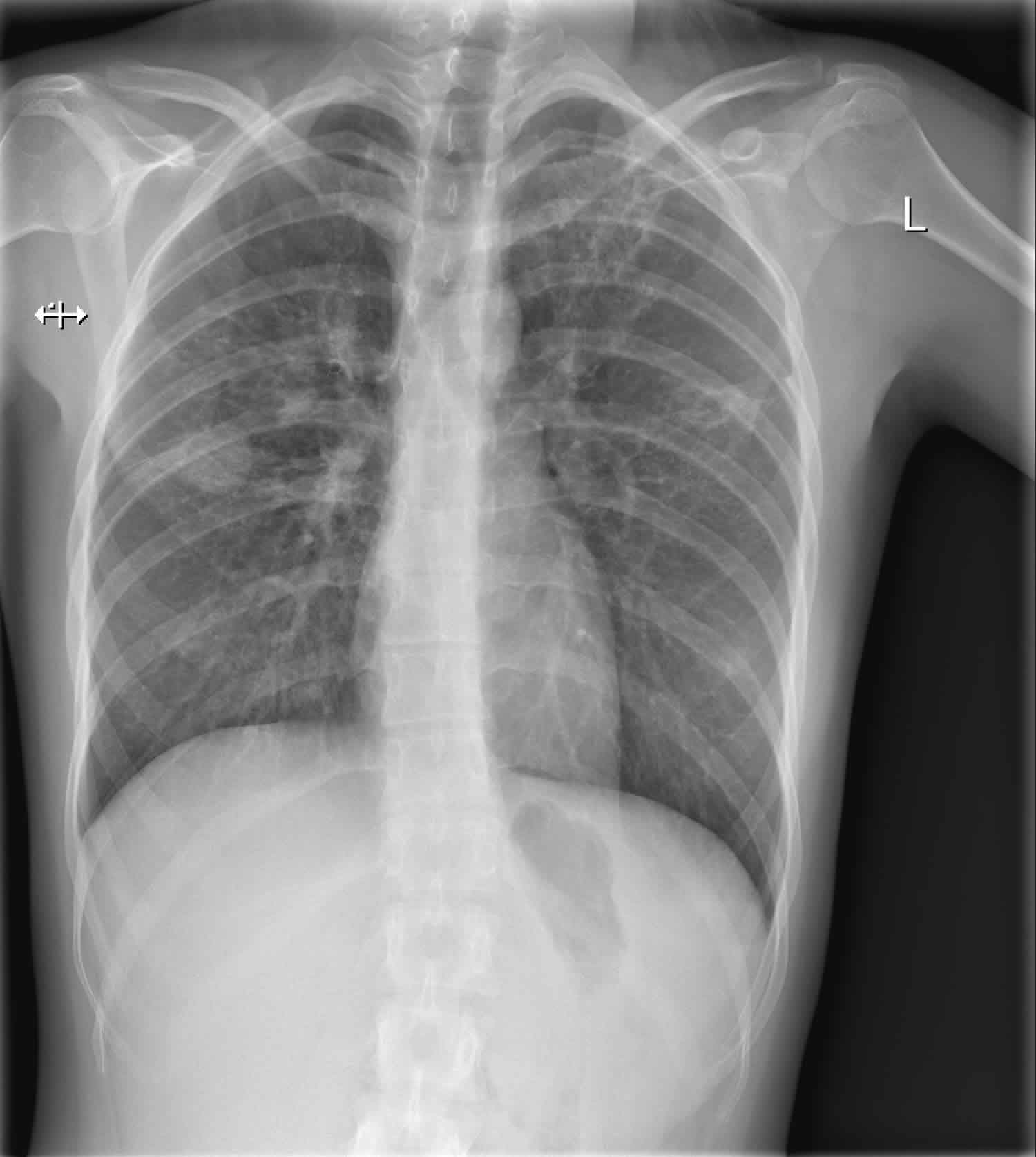

Figure 2. Tuberculosis chest x-ray

Footnote: Diffuse reticular and micronodular pattern with a predilection for upper and middle zones. There is a mass in the middle zone of the right lung and two cavities in the middle and upper zones of the left lung.

Is tuberculosis contagious?

Yes. You may have been exposed to tuberculosis bacteria if you spent time near someone with tuberculosis disease. The tuberculosis bacteria are put into the air when a person with active tuberculosis disease of the lungs or throat coughs, sneezes, speaks, or sings.

You cannot get tuberculosis from:

- Clothes

- Drinking glass

- Eating utensils

- Handshake

- Toilet

- Other surfaces

If you think you have been exposed to someone with tuberculosis disease, you should contact your doctor or local health department about getting a tuberculosis skin test or a special tuberculosis blood test. Be sure to tell the doctor or nurse when you spent time with the person who has tuberculosis disease.

It is important to know that a person who is exposed to tuberculosis bacteria is not able to spread the bacteria to other people right away. Only persons with active tuberculosis disease can spread tuberculosis bacteria to others. Before you would be able to spread tuberculosis to others, you would have to breathe in tuberculosis bacteria and become infected. Then the active bacteria would have to multiply in your body and cause active tuberculosis disease. At this point, you could possibly spread tuberculosis bacteria to others. People with tuberculosis disease are most likely to spread the bacteria to people they spend time with every day, such as family members, friends, coworkers, or schoolmates.

Some people develop tuberculosis disease soon (within weeks) after becoming infected, before their immune system can fight the tuberculosis bacteria. Other people may get sick years later, when their immune system becomes weak for another reason. Many people with tuberculosis infection never develop tuberculosis disease.

Tuberculosis causes

Tuberculosis is an infection caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis bacteria. It’s spread through the air—when an infected person coughs, sneezes, laughs, etc. However, it is not easy to become infected with tuberculosis. Usually, a person has to be close to someone with tuberculosis disease for a long period of time. tuberculosis is usually spread between family members, close friends, and people who work or live together. tuberculosis is spread most easily in closed spaces over a long period of time.

Most cases of active tuberculosis result from the activation of latent tuberculosis infections or old infections in people with impaired immune systems. People with clinically active tuberculosis will often but not always display symptoms and can spread the disease to others.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is an alcohol and acid-fast bacillus. It is part of a group of organisms classified as the M. tuberculosis complex. Other members of this group are, Mycobacterium africanum, Mycobacterium bovis, and Mycobacterium microti. Most other mycobacteria organisms are classified as non-tuberculous or atypical mycobacterial organisms.

Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a non-spore forming, non-motile, obligate-aerobic, facultative, catalase negative, intracellular bacteria. The organism is neither gram-positive nor gram-negative because of very poor reaction with the Gram stain. Weakly positive cells can sometimes be demonstrated on Gram stain, a phenomenon known as “ghost cells.”

The organism has several unique features compared to other bacteria such as the presence of several lipids in the cell wall including mycolic acid, cord factor, and Wax-D. The high lipid content of the cell wall is thought to contribute the following properties of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection:

- Resistance to several antibiotics

- Difficulty staining with Gram stain and several other stains

- Ability to survive under extreme conditions such as extreme acidity or alkalinity, low oxygen situation and intracellular survival(within the macrophage)

The first contact of the Mycobacterium organism with a host leads to manifestations known as primary tuberculosis. This primary tuberculosis is usually localized to the middle portion of the lungs, and this is known as the Ghon focus of primary tuberculosis. In most infected individuals, the Ghon focus enters a state of latency. This state is known as latent tuberculosis.

Latent tuberculosis is capable of being reactivated after immunosuppression in the host. A small proportion of people would develop an active disease following first exposure. Such cases are referred to as primary progressive tuberculosis. Primary progressive tuberculosis is seen in children, malnourished people, people with immunosuppression, and individuals on long-term steroid use.

Most people who develop tuberculosis, do so after a long period of latency (usually several years after initial primary infection). This is known as secondary tuberculosis. Secondary tuberculosis usually occurs because of reactivation of latent tuberculosis infection. The lesions of secondary tuberculosis are in the lung apices. A smaller proportion of people who develop secondary tuberculosis does so after getting infected a second time (re-infection).

The lesions of secondary tuberculosis are similar for both reactivation and reinfection in terms of location (at the lung apices), and the presence of cavitation enables a distinction from primary progressive tuberculosis which tends to be in the middle lung zones and lacks marked tissue damage or cavitation.

Multi-drug resistant tuberculosis

Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis is a very dangerous form of tuberculosis. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis refers to tuberculosis with strains of Mycobacterium which have developed resistance to the classic anti-tuberculosis medications. TB is especially a problem among patients with HIV/AIDS. Resistance to multiple anti-tuberculosis medications including at least the two standard anti-tuberculous medications, Rifampicin or Isoniazid, is required to make a diagnosis of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.

Seventy-five percent of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis is considered primary multi-drug resistant tuberculosis, caused by infection with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis pathogens. The remaining 25% are acquired and occur when a patient develops resistance to treatment for tuberculosis. Inappropriate treatment for tuberculosis because of several factors such as antibiotic abuse; inadequate dosage; incomplete treatment is the number one cause of acquired multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.

Drug-resistant tuberculosis can occur when the drugs used to treat tuberculosis are misused or mismanaged. For example:

- When people do not complete the full course of treatment;

- When healthcare providers prescribe the wrong treatment, the wrong dose, or wrong length of time for taking the drugs;

- When the supply of drugs is not always available; or

- When the drugs are of poor quality.

Drug-resistant tuberculosis is more common in people who:

- Do not take their tuberculosis drugs regularly

- Do not take all of their medications for the length of time the doctor recommended

- Develop tuberculosis disease again, after being treated for tuberculosis disease in the past

- Come from areas of the world where drug-resistant tuberculosis is common

- Have spent time with someone known to have drug-resistant tuberculosis disease

Extremely multi-drug resistant tuberculosis

This is a more severe type of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis. Extremely multi-drug resistant tuberculosis is an uncommon occurrence. Diagnosis requires resistance to at least four anti-tuberculous medications including resistance to Rifampicin, Isoniazid, and resistance to any two of the newer anti-tuberculous medications. The newer medications implicated in extremely multi-drug resistant tuberculosis are the fluoroquinolones (Levofloxacin and moxifloxacin) and the injectable second-line aminoglycosides, Kanamycin, Capreomycin, and amikacin.

Mechanism of developing extremely multi-drug resistant tuberculosis is similar to the mechanism for developing multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.

Risk factors for tuberculosis

The chances of getting infected by the tuberculosis bacteria are highest for people that are in close contact with others who are infected. This includes:

- Family and friends of a person with infectious tuberculosis disease

- People from parts of the world with high rates of tuberculosis, including India and parts of Asian and Africa.

- People in groups with high rates of tuberculosis transmission, including the homeless persons, injection drug users, and people living with HIV infection

- People who work or reside in facilities or institutions that house people who are at high risk for tuberculosis such as hospitals, homeless shelters, correctional facilities, nursing homes, and residential homes for those with HIV

Not everyone who is infected with the tuberculosis bacteria (latent tuberculosis) develops clinically active tuberculosis disease. People at highest risk for developing active tuberculosis disease are those with a weak immune system, including:

- Babies and young children, whose immune systems have not matured

- People with chronic conditions such as diabetes or kidney disease

- People with HIV/AIDS

- Organ transplant recipients

- Cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy

- People receiving certain specialized treatments for autoimmune disorders such as rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn’s disease

Some people develop tuberculosis disease soon after becoming infected (within weeks) before their immune system can fight the tuberculosis bacteria. Other people may get sick years later, when their immune system becomes weak for another reason.

Overall, about 5 to 10% of infected persons who do not receive treatment for latent tuberculosis infection will develop tuberculosis disease at some time in their lives. For persons whose immune systems are weak, especially those with HIV infection, the risk of developing tuberculosis disease is much higher than for persons with normal immune systems.

Generally, persons at high risk for developing tuberculosis disease fall into two categories:

- Persons who have been recently infected with tuberculosis bacteria

- Persons with medical conditions that weaken the immune system

1. Persons who have been recently infected with tuberculosis bacteria

This includes:

- Close contacts of a person with infectious tuberculosis disease

- Persons who have immigrated from areas of the world with high rates of tuberculosis

- Children less than 5 years of age who have a positive tuberculosis test

- Groups with high rates of tuberculosis transmission, such as homeless persons, injection drug users, and persons with HIV infection

- Persons who work or reside with people who are at high risk for tuberculosis in facilities or institutions such as hospitals, homeless shelters, correctional facilities, nursing homes, and residential homes for those with HIV

2. Persons with medical conditions that weaken the immune system

Babies and young children often have weak immune systems. Other people can have weak immune systems, too, especially people with any of these conditions:

- HIV infection (the virus that causes AIDS)

- Substance abuse

- Silicosis

- Diabetes mellitus

- Severe kidney disease

- Low body weight

- Organ transplants

- Head and neck cancer

- Medical treatments such as corticosteroids or organ transplant

- Specialized treatment for rheumatoid arthritis or Crohn’s disease.

More recently, the use of a monoclonal antibody targeting the inflammatory cytokine, tumor necrotic factor alpha (TNF-alpha) has been associated with an increased risk of tuberculosis. Antagonists of this cytokine include several monoclonal antibodies (biologics) used for the treatment of inflammatory disorders. Drugs in this category include infliximab, adalimumab, etanercept, and golimumab. Patients using any of these medications should be monitored for tuberculosis before and during the period of drug treatment.

Other major risk factors:

- Socio-economic factors: Poverty, malnutrition, wars

- Immunosuppression: HIV/AIDS, chronic immunosuppressive therapy (steroids, monoclonal antibodies against tumor necrotic factor), a poorly developed immune system (children, primary immunodeficiency disorders)

- Occupational: Mining, construction workers, pneumoconiosis (silicosis)

Tuberculosis transmission

Tuberculosis bacteria are spread through the air from one person to another. The TB bacteria are put into the air when a person with TB disease of the lungs or throat coughs, speaks, or sings. People nearby may breathe in these bacteria and become infected.

Tuberculosis is NOT spread by:

- shaking someone’s hand

- sharing food or drink

- touching bed linens or toilet seats

- sharing toothbrushes

- kissing

When a person breathes in tuberculosis bacteria, the bacteria can settle in the lungs and begin to grow. From there, they can move through the blood to other parts of the body, such as the kidney, spine, and brain.

Tuberculosis disease in the lungs or throat can be infectious. This means that the bacteria can be spread to other people. Tuberculosis in other parts of the body, such as the kidney or spine, is usually not infectious.

People with tuberculosis disease are most likely to spread it to people they spend time with every day. This includes family members, friends, and coworkers or schoolmates.

Tuberculosis prevention

If you have become infected with tuberculosis, but do not have active tuberculosis disease, you may get preventive therapy. This treatment kills germs that are not doing any damage right now, but could so do in the future. The most common preventive therapy is a daily dose of the medicine isoniazid (INH) for 6 to 9 months.

If you take your medicine as instructed by your healthcare provider, it can keep you from developing active tuberculosis disease.

There is a vaccine against tuberculosis called BCG or bacillus Calmette-Guerin. It is used in many foreign countries where tuberculosis is more common. However, it is not used very often in the United States because the chances of being infected with tuberculosis in the U.S. is low. It can also make tuberculosis skin tests less accurate. Recent evidence has shown that BCG is effective at reducing the incidence of tuberculosis in children by about half in populations with a high prevalence of active tuberculosis but is much less effective in adults.

Preventing exposure to tuberculosis disease while traveling abroad

In many countries, tuberculosis is much more common than in the United States. Travelers should avoid close contact or prolonged time with known tuberculosis patients in crowded, enclosed environments (for example, clinics, hospitals, prisons, or homeless shelters).

Although multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis are occurring globally, they are still rare. HIV-infected travelers are at greatest risk if they come in contact with a person with multidrug-resistant and extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis.

Air travel itself carries a relatively low risk of infection with tuberculosis of any kind. Travelers who will be working in clinics, hospitals, or other health care settings where tuberculosis patients are likely to be encountered should consult infection control or occupational health experts. They should ask about administrative and environmental procedures for preventing exposure to tuberculosis. Once those procedures are implemented, additional measures could include using personal respiratory protective devices.

Travelers who anticipate possible prolonged exposure to people with tuberculosis (for example, those who expect to come in contact routinely with clinic, hospital, prison, or homeless shelter populations) should have a tuberculosis skin test or a tuberculosis blood test before leaving the United States. If the test reaction is negative, they should have a repeat test 8 to 10 weeks after returning to the United States. Additionally, annual testing may be recommended for those who anticipate repeated or prolonged exposure or an extended stay over a period of years. Because people with HIV infection are more likely to have an impaired response to tuberculosis tests, travelers who are HIV positive should tell their physicians about their HIV infection status.

Preventing latent tuberculosis infection from progressing to tuberculosis disease

Many people who have latent tuberculosis infection never develop tuberculosis disease. But some people who have latent tuberculosis infection are more likely to develop tuberculosis disease than others. Those at high risk for developing tuberculosis disease include:

- People with HIV infection

- People who became infected with tuberculosis bacteria in the last 2 years

- Babies and young children

- People who inject illegal drugs

- People who are sick with other diseases that weaken the immune system

- Elderly people

- People who were not treated correctly for tuberculosis in the past

If you have latent tuberculosis infection and you are in one of these high-risk groups, you should take medicine to keep from developing tuberculosis disease. There are several treatment options for latent tuberculosis infection. You and your health care provider must decide which treatment is best for you. If you take your medicine as instructed, it can keep you from developing tuberculosis disease. Because there are less bacteria, treatment for latent tuberculosis infection is much easier than treatment for tuberculosis disease. A person with tuberculosis disease has a large amount of tuberculosis bacteria in the body. Several drugs are needed to treat tuberculosis disease.

Tuberculosis vaccine

Bacille Calmette-Guérin (BCG) is a vaccine for tuberculosis (tuberculosis) disease. This vaccine is not widely used in the United States, but it is often given to infants and small children in other countries where tuberculosis is common. BCG does not always protect people from getting tuberculosis.

BCG Recommendations

In the United States, BCG should be considered for only very select people who meet specific criteria and in consultation with a tuberculosis expert. Health care providers who are considering BCG vaccination for their patients are encouraged to discuss this intervention with the tuberculosis control program in their area.

Children

BCG vaccination should only be considered for children who have a negative tuberculosis test and who are continually exposed, and cannot be separated from adults who

- Are untreated or ineffectively treated for tuberculosis disease, and the child cannot be given long-term primary preventive treatment for tuberculosis infection; or

- Have tuberculosis disease caused by strains resistant to isoniazid and rifampin.

Health Care Workers

BCG vaccination of health care workers should be considered on an individual basis in settings in which

- A high percentage of tuberculosis patients are infected with tuberculosis strains resistant to both isoniazid and rifampin;

- There is ongoing transmission of drug-resistant tuberculosis strains to health care workers and subsequent infection is likely; or

- Comprehensive tuberculosis infection-control precautions have been implemented, but have not been successful.

Health care workers considered for BCG vaccination should be counseled regarding the risks and benefits associated with both BCG vaccination and treatment of latent tuberculosis infection.

Contraindications

- Immunosuppression. BCG vaccination should not be given to persons who are immunosuppressed (e.g., persons who are HIV infected) or who are likely to become immunocompromised (e.g., persons who are candidates for organ transplant).

- Pregnancy. BCG vaccination should not be given during pregnancy. Even though no harmful effects of BCG vaccination on the fetus have been observed, further studies are needed to prove its safety.

Types of tuberculosis

Not everyone infected with tuberculosis bacteria becomes sick. As a result, two tuberculosis-related conditions exist: latent tuberculosis infection and tuberculosis disease.

Table 1. The difference between Latent tuberculosis infection and tuberculosis disease

| A person with latent tuberculosis infection | A person with tuberculosis disease |

|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Latent tuberculosis infection

Tuberculosis bacteria can live in the body without making you sick. This is called latent tuberculosis infection. In most people who breathe in tuberculosis bacteria and become infected, the body is able to fight the TB bacteria to stop them from growing.

People with latent tuberculosis infection:

- Have no symptoms

- Don’t feel sick

- Can’t spread tuberculosis bacteria to others

- Usually have a positive tuberculosis skin test reaction or positive tuberculosis blood test

- May develop tuberculosis disease if they do not receive treatment for latent tuberculosis infection

Many people who have latent tuberculosis infection never develop tuberculosis disease. In these people, the tuberculosis bacteria remain inactive for a lifetime without causing disease. But in other people, especially people who have a weak immune system, the bacteria become active, multiply, and cause tuberculosis disease.

Tuberculosis disease

Tuberculosis bacteria become active if the immune system can’t stop them from growing. When tuberculosis bacteria are active (multiplying in your body), this is called tuberculosis disease. People with tuberculosis disease are sick. They may also be able to spread the bacteria to people they spend time with every day.

Many people who have latent tuberculosis infection never develop tuberculosis disease. Some people develop tuberculosis disease soon after becoming infected (within weeks) before their immune system can fight the tuberculosis bacteria. Other people may get sick years later when their immune system becomes weak for another reason.

For people whose immune systems are weak, especially those with HIV infection, the risk of developing tuberculosis disease is much higher than for people with normal immune systems.

Signs and symptoms of tuberculosis

Symptoms of tuberculosis disease depend on where in the body the tuberculosis bacteria are growing. TB bacteria usually grow in the lungs (pulmonary tuberculosis). Tuberculosis disease in the lungs may cause symptoms such as:

- a bad cough that lasts 3 weeks or longer

- pain in the chest

- coughing up blood or sputum (phlegm from deep inside the lungs)

Other symptoms of tuberculosis disease are:

- weakness or fatigue

- weight loss

- no appetite

- chills

- fever

- sweating at night

Symptoms of tuberculosis disease in other parts of the body depend on the area affected.

People who have latent tuberculosis infection do not feel sick, do not have any symptoms, and cannot spread tuberculosis to others.

Tuberculosis complications

Most patients have a relatively benign course. Complications are more frequently seen in patients with the risk factors mentioned above. Some of the complications associated with tuberculosis are:

- Extensive lung destruction

- Damage to cervical sympathetic ganglia leading to Horner’s syndrome.

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome

- Milliary spread (disseminated tuberculosis) including tuberculosis meningitis.

- Empyema

- Pneumothorax

- Systemic amyloidosis

Tuberculosis diagnosis

Tuberculosis can be detected through a skin test or a tuberculosis blood test. A positive tuberculosis skin test or tuberculosis blood test only tells that a person has been infected with tuberculosis bacteria. It does not tell whether the person has latent tuberculosis infection or has progressed to tuberculosis disease. Other tests, such as a chest x-ray and a sample of sputum, are needed to see whether the person has tuberculosis disease.

The skin test is done by injecting a small amount of fluid called tuberculin into the skin in the arm. You will be told to return within 48 to 72 hours to have a healthcare worker check the arm to see if a bump or an induration (thickening) of the skin has developed. These may be difficult to feel and an experienced healthcare worker should examine the reaction. The healthcare worker will measure the bump or induration and tell you if your reaction to the test is positive or negative. If it’s positive, it usually means you have been infected with the tuberculosis germ. It does not tell whether you have developed clinically active tuberculosis disease.

The tuberculosis blood test measures how your immune system reacts to the germs that cause tuberculosis. If you have a positive test for tuberculosis infection, it only means that you have been infected with tuberculosis germs. It does not tell whether you have developed clinically active tuberculosis disease. You will be given other tests, such as a chest X-ray and a check of your sputum (coughed up mucus), to see whether you have clinically active tuberculosis disease.

However, many countries still rely on a long-used method called sputum smear microscopy to diagnose tuberculosis. Trained laboratory technicians look at sputum samples under a microscope to see if tuberculosis bacteria are present. Microscopy detects only half the number of tuberculosis cases and cannot detect drug-resistance. The use of the rapid test Xpert MTB/RIF® has expanded substantially since 2010, when World Health Organization (WHO) first recommended its use. The test simultaneously detects tuberculosis and resistance to rifampicin, the most important tuberculosis medicine. Diagnosis can be made within 2 hours and the test is now recommended by WHO as the initial diagnostic test in all persons with signs and symptoms of tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis screening tests

Tuberculosis screening test checks to see if you have been infected with TB. Tuberculosis is a serious bacterial infection that mainly affects the lungs. It can also affect other parts of the body, including the brain, spine, and kidneys. tuberculosis is spread from person to person through coughing or sneezing.

Not everyone infected with tuberculosis gets sick. Some people have an inactive form of the infection called latent tuberculosis. When you have latent tuberculosis, you don’t feel sick and can’t spread the disease to others.

Many people with latent tuberculosis will never feel any symptoms of the disease. But for others, especially those who have or develop weakened immune systems, latent tuberculosis can turn into a far more dangerous infection called active tuberculosis. If you have active tuberculosis, you may feel very sick. You may also spread the disease to other people. Without treatment, active tuberculosis can cause serious illness or even death.

There are two types of tuberculosis tests used for screening: a tuberculosis skin test (Mantoux test or PPD test) and a tuberculosis blood test (IGRA test). These tests can show if you have ever been infected with tuberculosis. They don’t show if you have a latent or active tuberculosis infection. More tests will be needed to confirm or rule out a diagnosis.

A positive screening test indicates exposure to tuberculosis and a high chance of developing active tuberculosis in the future. Tuberculosis incidence in patients with positive Mantoux skin test averages between 2% to 10% without treatment.

Patients with a positive test should have a chest x-ray as a minimum diagnostic test. In some cases, these patients should have additional tests. Patients meeting the criteria for latent tuberculosis should receive prophylaxis with isoniazid.

You may need a tuberculosis skin test or tuberculosis blood test if you have symptoms of an active tuberculosis infection or if you have certain factors that put you at higher risk for getting tuberculosis.

Symptoms of an active tuberculosis infection include:

- Cough that lasts for three weeks or more

- Coughing up blood

- Chest pain

- Fever

- Fatigue

- Night sweats

- Unexplained weight loss

In addition, some childcare centers and other facilities require tuberculosis testing for employment.

You may be at higher risk for getting tuberculosis if you:

- Are a health care worker who cares for patients who have or are at high risk for getting tuberculosis

- Live or work in a place with a high rate of tuberculosis infection. These include homeless shelters, nursing homes, and prisons.

- Have been exposed to someone who has an active tuberculosis infection

- Have HIV or another disease that weakens your immune system

- Use illegal drugs

- Have traveled or lived in an area where tuberculosis is more common. These include countries in Asia, Africa, Eastern Europe, Latin America, and the Caribbean, and in Russia.

Tuberculin skin testing

In Mantoux test or skin testing with PPD (purified protein derivative), the Mantoux reaction following injection of a dose of PPD (purified protein derivative) is the traditional screening test for exposure to tuberculosis. The result is interpreted taking into consideration the patient’s overall risk of exposure. Patients are classified into 3 groups based on the risk of exposure with three corresponding cut-off points. The 3 major groups used are discussed below.

Low Risk

- Individuals with minimal probability of exposure are considered to have a positive Mantoux test only if there is very significant induration following intradermal injection of PPD. The cut-off point for this group of people (with minimal risk of exposure) is taken to be 15 mm.

Intermediate Risk

- Individuals with intermediate probability are considered positive if the induration is greater than 10 mm.

High Risk

- Individuals with a high risk of a probability of exposure are considered positive if the induration is greater than 5 mm.

Examples of Patients in the Different Risk Categories

- Low Risk/Low Probability: Patients with no known risk of exposure to tuberculosis. Example: No history of travel, military service, HIV-negative, no contact with a chronic cough patient, no occupational exposure, no history of steroids. Not a resident of a tuberculosis-endemic region.

- Intermediate Risk/Probability: Residents of tuberculosis-endemic countries (Latin America, Sub -Sahara Africa, Asia), workers or residents of shelters, Medical or microbiology department personnel.

- High Risk/Probability: HIV-positive patient, a patient with evidence of the previous tuberculosis such as the healed scar on an x-ray), contact with chronic cough patients.

Note that a Mantoux test indicates exposure or latent tuberculosis. However, this test lacks specificity, and patients would require subsequent visits for interpreting the results as well as chest x-ray for confirmation. Although relatively sensitive, the Mantoux reaction is not very specific and may give false positive reactions in individuals who have been exposed to the BCG-vaccine.

Screening in immunocompromised patients

Immunocompromised patients may show lower levels of reaction to PPD or false negative Mantoux because of cutaneous anergy.

A high level of suspicion should be entertained when reviewing negative screening tests for tuberculosis in HIV-positive individuals.

IGRA test

Interferon Gamma Release Assay (IGRA) also called Quantiferon assays is a tuberculosis blood test that is more specific and equally as sensitive as the Mantoux skin test. IGRA test assays for the level of the inflammatory cytokine, especially interferon gamma.

The advantages of IGRA test, especially in those with prior vaccination with BCG vaccine, includes, the test requires a single blood draw, obviating the need for repeat visits to interpret results. Furthermore, additional investigations such as HIV screening could be performed (after patient consent) on the same blood draw.

IGRA test’s disadvantages include cost and the technical expertise required to perform the test.

Screening questionnaires for resource-poor settings

Several screening questionnaires have been validated to enable healthcare workers working in remote and resource-poor environments screen for tuberculosis.

These questionnaires make use of an algorithm that combines several clinical signs and symptoms of tuberculosis. Some of the commonly used symptoms are:

- Chronic cough

- Weight loss

- Fever and night sweats

- History of contact

- HIV status

- Blood in sputum

Several studies have confirmed the utility of using several criteria rather than a focus on only chronic cough or weight loss.

Testing for tuberculosis in BCG-vaccinated people

Many people born outside of the United States have been BCG-vaccinated.

People who were previously vaccinated with BCG may receive a tuberculosis skin test to test for tuberculosis infection. Vaccination with BCG may cause a positive reaction to a tuberculosis skin test. A positive reaction to a tuberculosis skin test may be due to the BCG vaccine itself or due to infection with tuberculosis bacteria.

Tuberculosis blood tests (IGRAs), unlike the tuberculosis skin test, are not affected by prior BCG vaccination and are not expected to give a false-positive result in people who have received BCG.

For children under the age of five, the tuberculosis skin test is preferred over tuberculosis blood tests.

A positive tuberculosis skin test or tuberculosis blood test only tells that a person has been infected with tuberculosis bacteria. It does not tell whether the person has latent tuberculosis infection or has progressed to tuberculosis disease. Other tests, such as a chest x-ray and a sample of sputum, are needed to see whether the person has tuberculosis disease.

Confirmatory and diagnostic tests

- A chest x-ray is indicated to rule out or rule in the presence of active disease in all screening test positive cases.

- Acid Fast Staining-Ziehl-Neelsen. The Ziehl-Neelsen stain is one of the most commonly used stains to diagnose tuberculosis. The sample is initially stained with carbol fuchsin (pink color stain), decolorized with acid -alcohol and then counter-stained with another stain(usually, blue colored methylene blue). A positive sample would retain the pink color of the original carbol fuchsin, hence the designation, alcohol and acid-fast bacillus.

- Culture

- Nuclear Amplification and Gene-Based Tests: These represent a new generation of diagnostic tools for tuberculosis. These tests enable identification of the bacteria or bacteria particles making use of DNA-based molecular techniques. Examples are Genexpert and DR-Mtuberculosis.

The new molecular-based techniques are faster and enable rapid diagnosis with high precision. Confirmation of tuberculosis could be made in hours rather than the days or weeks it takes to wait for a standard culture. This is very important, especially among immunocompromised host where there is a high rate of false negative results. Some molecular-based tests such as GeneXpert and DR-Mtuberculosis also allow for identification of multi-drug resistant tuberculosis.

Tuberculosis treatment

Treatment for tuberculosis depends on whether a person has clinically active tuberculosis disease or only tuberculosis infection (latent TB infection). Without treatment latent tuberculosis infection can progress to tuberculosis disease. If not treated properly, tuberculosis disease can be fatal.

If you have become infected with TB and you do not have symptoms, and you cannot spread TB bacteria to others, this is called latent tuberculosis, you should get preventive therapy. This treatment kills germs that are not doing any damage right now, but could so do in the future. Latent TB bacteria can become active in the body and multiply, the person will go from having latent TB infection to being sick with active TB disease. For this reason, people with latent TB infection should be treated to prevent them from developing TB disease. As of 2018, there are four Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommended treatment regimens for latent tuberculosis infection that use isoniazid, rifapentine and/or rifampin. All the regimens are effective. Healthcare providers should prescribe the more convenient shorter regimens, when possible. Patients are more likely to complete shorter treatment regimens. Treatment must be modified if the patient is a contact of an individual with drug-resistant tuberculosis disease. Consultation with a tuberculosis expert is advised if the known source of tuberculosis infection has drug-resistant tuberculosis. The CDC has updated the recommendations for use of once-weekly isoniazid-rifapentine for 12 weeks (3HP) for treatment of latent tuberculosis infection.

In the United States, up to 13 million people may have latent TB infection. Without treatment, on average 1 in 10 people with latent TB infection will get sick with TB disease in the future. The risk is higher for people with HIV, diabetes, or other conditions that affect the immune system. More than 80% of people who get sick with TB disease in the United States each year get sick from untreated latent TB infection.

If you have active tuberculosis disease you will probably be treated with a combination of several drugs for 6 to 12 months. You may only have to stay a short time in the hospital, if at all, and can then continue taking medication at home. After a few weeks, you can probably even return to normal activities and not have to worry about infecting others.

The most common treatment for active tuberculosis is isoniazid plus three other drugs—rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. You will probably begin to feel better only a few weeks after starting to take the drugs.

It is very important that you continue to take the medicine correctly (regularly and under medical supervision) for the full length of treatment. If you are being treated in a public clinic you may be asked to take your medicines in the presence of a healthcare worker who will ensure that you have done so. This is called Directly Observed Therapy (DOT).

TB antibiotics

Treatment regimens for latent tuberculosis infection

Groups Who Should be Given High Priority for Latent tuberculosis Infection Treatment include:

- People with a positive tuberculosis blood test (interferon-gamma release assay or IGRA).

- People with a tuberculin skin test reaction of 5 or more millimeters who are:

- HIV-infected persons.

- Recent contacts to a patient with active tuberculosis disease.

- Persons with fibrotic changes on chest radiograph consistent with old tuberculosis.

- Organ transplant recipients.

- Persons who are immunosuppressed for other reasons (e.g., taking the equivalent of >15 mg/day of prednisone for 1 month or longer, taking TNF-α antagonists).

- People with a tuberculin skin test reaction of 10 or more millimeters who are:

- From countries where tuberculosis is common, including Mexico, the Philippines, Vietnam, India, China, Haiti, and Guatemala, or other countries with high rates of tuberculosis. Of note, people born in Canada, Australia, New Zealand, or Western and Northern European countries are not considered at high risk for tuberculosis infection, unless they spent time in a country with a high rate of tuberculosis.

- Injection drug users.

- Residents and employees of high-risk congregate settings (e.g., correctional facilities, nursing homes, homeless shelters, hospitals, and other health care facilities).

- Mycobacteriology laboratory personnel.

- Children under 4 years of age, or children and adolescents exposed to adults in high-risk categories.

Persons with no known risk factors for tuberculosis may be considered for treatment of latent TB infection if they have either a positive IGRA result or if their reaction to the tuberculin skin test is 15 mm or larger. However, targeted tuberculosis testing programs should only be conducted among high-risk groups. All testing activities should be accompanied by a plan for follow-up care for persons with latent tuberculosis infection or disease.

The four treatment regimens for latent tuberculosis infection use isoniazid, rifapentine, or rifampin. While all the regimens are effective, healthcare providers should prescribe the more convenient shorter regimens, when possible. Patients are more likely to complete shorter treatment regimens.

Treatment must be modified if the patient is a contact of an individual with drug-resistant tuberculosis disease. Consultation with a tuberculosis expert is advised if the known source of tuberculosis infection has drug-resistant tuberculosis.

CDC has updated the recommendations for use of once-weekly isoniazid-rifapentine for 12 weeks for treatment of latent tuberculosis infection.

Table 2. Latent tuberculosis infection treatment regimens

| Drug(s) | Duration | Dose | Frequency | Total Doses |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isoniazid* and Rifapentine† | 3 months | Adults and Children aged 12 years and older: Isoniazid: 15 mg/kg rounded up to the nearest 50 or 100 mg; 900 mg maximum Rifapentine: 10–14.0 kg 300 mg 14.1–25.0 kg 450 mg 25.1–32.0 kg 600 mg 32.1–49.9 kg 750 mg ≥50.0 kg 900 mg maximum Children aged 2–11 years: Isoniazid*: 25 mg/kg; 900 mg maximum Rifapentine†: as above | Once weekly‡ | 12 |

| Rifampin§ | 4 months | Adult: 10 mg/kg Children: 15–20 mg/kg‖ Maximum dose: 600 mg | Daily | 120 |

| Isoniazid | 9 months | Adult: 5 mg/kg Children: 10–20 mg/kg¶ Maximum dose: 300 mg | Daily | 270 |

| Adult:15 mg/kgChildren: 20–40 mg/kg¶Maximum dose: 900 mg | Twice weekly‡ | 76 | ||

| 6 months | Adult: 5 mg/kgChildren: Not recommendedMaximum dose: 300 mg | Daily | 180 | |

| Adult: 15 mg/kgChildren: Not recommendedMaximum dose: 900 mg | Twice weekly‡ | 52 |

Footnotes:

*Isoniazid (INH) is formulated as 100 mg and 300 mg tablets.

†Rifapentine (RPT) is formulated as 150 mg tablets in blister packs that should be kept sealed until use.

‡Intermittent regimens must be provided via directly observed therapy (DOT), that is, a health care worker observes the ingestion of medication.

§Rifampin (rifampicin; RIF) is formulated as 150 mg and 300 mg capsules.

‖The American Academy of Pediatrics acknowledges that some experts use rifampicin at 20–30 mg/kg for the daily regimen when prescribing for infants and toddlers 3.

¶The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends an isoniazid dosage of 10–15 mg/kg for the daily regimen and 20–30 mg/kg for the twice weekly regimen.

Treatment for tuberculosis disease

When tuberculosis bacteria become active (multiplying in your body) and your immune system can’t stop the tuberculosis bacteria from growing, this is called tuberculosis disease. Tuberculosis disease will make a person sick. People with tuberculosis disease may spread the bacteria to people with whom they spend many hours.

It is very important that people who have tuberculosis disease are treated, finish the medicine, and take the drugs exactly as prescribed. If they stop taking the drugs too soon, they can become sick again; if they do not take the drugs correctly, the tuberculosis bacteria that are still alive may become resistant to those drugs. tuberculosis that is resistant to drugs is harder and more expensive to treat.

Tuberculosis disease can be treated by taking several drugs for 6 to 9 months. There are 10 drugs currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treating tuberculosis. Of the approved drugs, the first-line anti-tuberculosis agents that form the core of treatment regimens are:

- Isoniazid

- Rifampin

- Ethambutol

- Pyrazinamide

Tuberculosis regimens for drug-susceptible tuberculosis

Regimens for treating tuberculosis disease have an intensive phase of 2 months, followed by a continuation phase of either 4 or 7 months (total of 6 to 9 months for treatment).

Table 3. Drug susceptible tuberculosis disease treatment regimens

Footnotes: Use of once-weekly therapy with Isoniazid 900 mg and rifapentine 600 mg in the continuation phase is not generally recommended. In uncommon situations where more than once-weekly Directly Observed Therapy is difficult to achieve, once-weekly continuation phase therapy with Isoniazid 900 mg plus rifapentine 600 mg may be considered for use only in HIV uninfected persons without cavitation on chest radiography.

- a. Other combinations may be appropriate in certain circumstances; additional details are provided in the Official American Thoracic Society/Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Infectious Diseases Society of America Clinical Practice Guidelines: Treatment of Drug-Susceptible Tuberculosisexternal icon.

- b. When Directly Observed Therapy is used, drugs may be given 5 days per week and the necessary number of doses adjusted accordingly. Although there are no studies that compare 5 with 7 daily doses, extensive experience indicates this would be an effective practice. Directly Observed Therapy should be used when drugs are administered less than 7 days per week.

- c. Based on expert opinion, patients with cavitation on initial chest radiograph and positive cultures at completion of 2 months of therapy should receive a 7-month (31-week) continuation phase.

- d. Pyridoxine (vitamin B6), 25–50 mg/day, is given with Isoniazid to all persons at risk of neuropathy (e.g., pregnant women; breastfeeding infants; persons with HIV; patients with diabetes, alcoholism, malnutrition, or chronic renal failure; or patients with advanced age). For patients with peripheral neuropathy, experts recommend increasing pyridoxine dose to 100 mg/day.

- e. Alternatively, some U.S. TB control programs have administered intensive-phase regimens 5 days per week for 15 doses (3 weeks), then twice weekly for 12 doses.

Continuation Phase of Treatment

The continuation phase of treatment is given for either 4 or 7 months. The 4-month continuation phase should be used in most patients. The 7-month continuation phase is recommended only for the following groups:

- Patients with cavitary pulmonary tuberculosis caused by drug-susceptible organisms and whose sputum culture obtained at the time of completion of 2 months of treatment is positive;

- Patients whose intensive phase of treatment did not include Pyrazinamide;

- Patients with HIV who are not receiving antiretroviral treatment (ART) during tuberculosis treatment; and

- Patients being treated with once weekly Isoniazid and rifapentine and whose sputum culture obtained at the time of completion of the intensive phase is positive.

- (Note: Use of once-weekly therapy with Isoniazid 900 mg and rifapentine 600 mg in the continuation phase is not generally recommended. In uncommon situations where more than once-weekly DOT is difficult to achieve, once-weekly continuation phase therapy with Isoniazid 900 mg plus rifapentine 600 mg may be considered for use only in HIV uninfected persons without cavitation on chest radiography.)

Treatment for drug-resistant tuberculosis

Drug-resistant tuberculosis is caused by tuberculosis bacteria that are resistant to at least one first-line anti-tuberculosis drug. Multidrug-resistant tuberculosis is resistant to more than one anti-tuberculosis drug and at least isoniazid and rifampin.

Extensively drug-resistant tuberculosis is a rare type of multidrug-resistant tuberculosis that is resistant to isoniazid and rifampin, plus any fluoroquinolone and at least one of three injectable second-line drugs (i.e., amikacin, kanamycin, or capreomycin).

Treating and curing drug-resistant tuberculosis is complicated. Inappropriate management can have life-threatening results. Drug-resistant tuberculosis should be managed by or in close consultation with an expert in the disease.

Side effect associated with most commonly used anti-tuberculosis drugs

- Isoniazid- Asymptomatic elevation of Aminotransferases (10-20%), Clinical Hepatitis (0.6%), Peripheral neurotoxicity, Hypersensitivity 4.

- Rifampin- Pruritis, Nausea & Vomiting, Flulike symptoms, Hepatotoxicity, Orange discoloration of bodily fluid.

- Rifabutin- Neutropenia, Uveitis (0.01%), Polyarthralgias, Hepatotoxicity (1%)

- Rifapentine- Similar to Rifampin

- Pyrazinamide- Hepatotoxicity (1%), Nausea & Vomiting, Polyarthralgias (40%), Acute gouty arthritis, Rash and photosensitive dermatitis

- Ethambutol- Retrobulbar neuritis (18%)

One of the most important aspects of tuberculosis treatment is close follow up and monitoring for these side effects. Most of these side effects can be managed by either close monitoring or adjusting dose. In some cases, the medication needs to be discontinued and second-line therapy should be considered if other alternatives are not available.

Living with tuberculosis

While you are in treatment for active tuberculosis disease, you will need regular checkups to make sure your treatment is working. You must finish your medicine and take the drugs exactly as prescribed. If you stop taking the drugs too soon you can become sick again and potentially spread the disease to others around you. If you do not take the drugs correctly, the tuberculosis germs that are still alive can become resistant to the drugs.

Sometimes the drugs used to treat tuberculosis can cause side effects. Side effects of tuberculosis drugs depend on which drugs you are taking and how your body reacts to the medication. Everyone is different. Common side effects include:

- upset stomach, nausea and vomiting or loss of appetite.

- tingling or numbness in the hands or feet

- itchy skin, rashes or bruising

- changes in your eyesight or blurred visions

- yellowish skin or eyes

- dark-colored urine

- weakness, fatigue or fever that for 3 or more days

It is important to tell your doctor or tuberculosis nurse immediately if you begin having any unusual symptoms while taking medicine for either preventive therapy or for active tuberculosis disease. tuberculosis drugs can be toxic to your liver, and your side effects may be a warning sign of liver damage. If you are having trouble with tingling and numbness, you doctor may prescribe a vitamin B6 supplement while you are in treatment. It may also be possible to change tuberculosis medications if your side effects are serious.

Don’t spread your tuberculosis

If you have active tuberculosis disease, it will take a few weeks of treatment before you can’t spread tuberculosis bacteria to others. Until your healthcare provider tells you to go back to your daily routine, here are ways to protect yourself and others near you:

- Take your medicine exactly as the healthcare provider directed.

- When you cough, sneeze or laugh, cover your mouth with a tissue. Put the tissue in a closed bag and throw it away.

- Do not go to work or school until your healthcare provider says it’s OK to go back. Avoid close contact with anyone. Sleep in a bedroom alone.

- Air out your room often so the tuberculosis germs don’t stay in the room and infect someone who breathes the air.

Tuberculosis prognosis

Majority of patients with a diagnosis of tuberculosis have a good outcome. This is mainly because of effective treatment. Without treatment mortality rate for tuberculosis is more than 50%.

The following group of patients is more susceptible to worse outcomes or death following tuberculosis infection:

- Extremes of age, elderly, infants and young children

- Delay in receiving treatment

- Radiologic evidence of extensive spread.

- Severe respiratory compromise requiring mechanical ventilation

- Immunosuppression

- Multidrug Resistance Tuberculosis.

- Tuberculosis (TB). https://www.who.int/tb/en/[↩]

- Adigun R, Singh R. Tuberculosis. [Updated 2019 Feb 6]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441916[↩]

- American Academy of Pediatrics. Tuberculosis. In: Kimberlin DW, Brady MT, Jackson MA, Long SS, eds. Red Book: 2018 Report of the Committee on Infectious Diseases. 31st ed. Itasca, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2018:829–853[↩]

- Metushi I, Uetrecht J, Phillips E. Mechanism of isoniazid-induced hepatotoxicity: then and now. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2016 Jun;81(6):1030-6.[↩]