Vaccinia virus

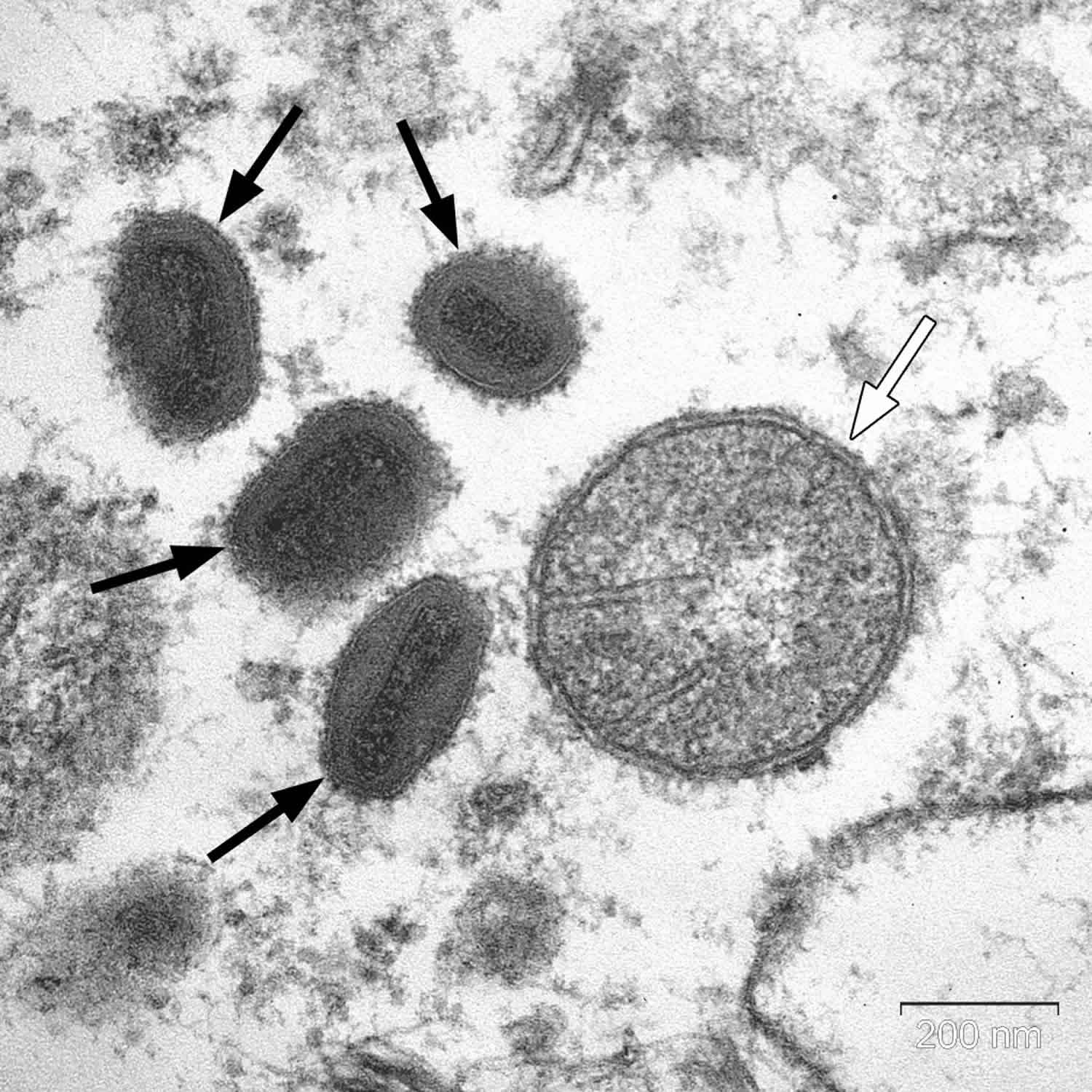

Vaccinia virus is a member of the orthopoxvirus genus of the Chordopoxvirinae subfamily 1. Vaccinia virus has a linear, double-stranded DNA genome approximately 190 kb in length, which encodes about 200 genes. Physically, the vaccinia virus particle is the shape of a brick, averaging 270 × 350 nm in size. Although the exact origins of vaccinia virus are uncertain, vaccinia virus may represent a hybrid of the variola and cowpox viruses 2. Vaccination with vaccinia virus has been directly responsible for the successful eradication of smallpox (variola virus). Routine childhood immunization for smallpox in the general population was officially discontinued in the United States in 1972 3.

During 2003, because of the concern for biological warfare, the United States government recommended that all first responders be vaccinated with the vaccinia virus. However, vaccination of first responders was halted upon the occurrence of vaccination-related complications, including a previously unrecognized complication, cardiomyopathy. Certain military recruits continue to receive vaccinia vaccine owing to the concern for bioterrorism. Laboratory personnel working with vaccinia and others for whom the benefits outweigh the risks of vaccination may also receive vaccinations

Vaccinia virus is usually administered via either intradermal scarification or injection. A bifurcated needle is used to apply the vaccine by pressing in and out of the skin of the upper deltoid region of the arm 5 times for a primary vaccination and 15 times for a revaccination.

Typically, a papule appears 4-5 days after vaccination secondary to local replication of the virus. The papule becomes pustular within 7-10 days and reaches a maximum size of 2-4 cm; this is known as a Jennerian pustule. At this time, associated axillary lymphadenopathy and mild fever may occur. The pustule contains fluid with live viral particles that can spread by direct contact. Two to 3 weeks after vaccination, the pustule dries from the center and forms a scab. A characteristic scar that is approximately 1 cm in diameter usually remains as evidence of prior vaccination. Revaccination yields a similar, yet accelerated, course of events. No evidence exists for systemic viremia during administration of vaccinia virus in immunocompetent individuals.

A Jennerian pustule indicates a successful primary vaccination and is classified as a major reaction. Reactions other than a Jennerian pustule are classified as equivocal and require a subsequent vaccination. Full immunity is conferred in more than 95% of persons for 5-10 years in a successful primary vaccination; successful revaccination allows 10-20 years of protection or more. Neutralizing antibodies have been found in some vaccinees up to 75 years following vaccination. Of note, antibodies to vaccinia are also protective against other Orthopox viruses (monkeypox and cowpox) and may decrease the severity of smallpox if administered within a few days of exposure.

Vaccinia virus induces immunity through both T-cell and B-cell responses. The B-cell response is evident from the presence of vaccinia-specific circulating antibodies for years after vaccination. The T-cell responses may be more important because full protection against smallpox was observed in children with agammaglobulinemia who could not mount an antibody response and who were immunized with vaccinia virus. CD8+ T-cell responses are essential for immunity, whereas CD4+ T cells are thought to contribute to long-lasting protection against vaccinia virus.

Most adverse reactions to vaccinia administration involve the skin and central nervous system (CNS). Progressive vaccinia, also known as vaccinia necrosum, is a rare complication in which viremia can lead to metastatic infection of the organs, necrosis of the skin, and, in some cases, death in immunosuppressed patients, particularly those with T-cell deficiencies. In children younger than 15 years who have eczema, vaccinia virus can also replicate rapidly in the eczematous lesions, leading to eczema vaccinatum. The sequelae of eczema vaccinatum include prolonged hospital stays and, occasionally, death.

Recent research has shown that patients with atopic dermatitis have an overabundance of a class A scavenger receptor known as macrophage receptor with collagenous structure on keratinocytes. Vaccinia virus bound directly to macrophage receptor with collagenous structure increases susceptibility to eczema vaccinatum. This breakthrough represents a potential area for future therapeutic strategies to prevent vaccinia virus infection in patients with increased susceptibility 4.

Central nervous system (CNS) effects are also rare and include microglial encephalitis and postvaccinial encephalopathy. The former occurs most often in people older than 2 years and is characterized by fever, headaches, seizures, and coma. The latter occurs in children younger than 2 years and causes diffuse cerebral edema and cerebral hemorrhage. Permanent neurological sequelae and death can result. Adults may rarely experience a less severe central nervous system reaction consisting of a demyelinating process. Definite predisposing factors have not been identified for people at risk of central nervous system complications, but the incidence varied with the strain of vaccinia virus used.

Vaccinia virus can also be spread from draining primary vaccination sites to the eyes, eyelids, nose, and perineum, causing mild inflammatory reactions or, rarely, a more serious ocular infection. Vaccination sites should be covered with protective bandages to prevent local spread and accidental infection. Shedding of the virus can occur for up to 21 days following vaccination. Vaccinia virus should not be administered to children younger than 3 years, individuals with eczema or central nervous system disorders, or immunosuppressed individuals.

Individuals vaccinated within the preceding 21 days can also spread the virus to unvaccinated contacts. In particular, these individuals should avoid contact with young children, immunocompromised persons, pregnant persons, and individuals with a history of atopic dermatitis. If this contact is unavoidable, vaccinated individuals should ensure proper hand hygiene and apply an occlusive dressing to the vaccination site to prevent inadvertent transmission 5.

Because of concerns about vaccine-related adverse events, diluted forms of both Dryvax and Pasteur were studied for safety and efficacy. The results showed that highly diluted first-generation vaccines caused less fever and loss of productivity while demonstrating similar levels of serum neutralizing antibody compared with undiluted forms of these vaccines. 6.

Although vaccinia virus is no longer necessary to prevent smallpox in the general population, vaccinia is now used to generate live recombinant vaccines for the treatment of other illnesses. Vaccinia virus can accept as much as 25 kb of foreign DNA, making it useful for expressing large eukaryotic and prokaryotic genes. Foreign genes are integrated stably into the viral genome, resulting in efficient replication and expression of biologically active molecules. Furthermore, posttranslational modifications (eg, methylation, glycosylation) occur normally in the infected cells.

The methods for constructing recombinant vaccinia viruses are well established. Recombinant shuttle plasmids are commonly used for placing a foreign gene into a nonessential region of the parental wild-type vaccinia virus. The plasmids contain a cloning site for insertion of the gene of interest, a selectable marker gene (eg, LacZ) or an antibiotic resistance gene, and flanking portions of a nonessential vaccinia gene. The cotransfection of the recombinant plasmid and a wild-type vaccinia virus into susceptible cells in culture results in homologous recombination between the plasmid and the vaccinia genome. Selection of recombinant viruses is possible using the selectable markers found only on the shuttle plasmid. The recombinant viruses can be purified and characterized for gene expression.

Recombinant vaccinia technology has resulted in numerous vaccine constructs targeting both infectious diseases and cancer. A recombinant vaccinia virus expressing the rabies glycoprotein was effective in preventing rabies in wild foxes. Vaccines targeted against HIV, malaria, hepatitis, and other infectious diseases have been generated and are being evaluated in clinical trials. Modified vaccinia Ankara is being considered as a candidate pandemic influenza H5N1 vaccine 7. The expression of human tumor antigens in vaccinia virus has been evaluated for the treatment of diverse types of cancer, including gastrointestinal tumors, malignant melanoma, breast cancer, cervical cancer, colorectal cancer, renal cell carcinoma, and hormone-refractory prostate cancer 1. Although these studies are in an early stage of development, the likelihood for exposure to vaccinia virus in the general population is expected to increase over the next several years 8.

Vaccinia virus causes

The causes of vaccinia infection are generally due to intentional vaccination; however, cases of infection by direct contact with a recently vaccinated individual have been reported. Furthermore, with the increasing interest in poxviruses for foreign gene transfer, risk of accidental infection of laboratory workers and medical personnel is increasing.

Vaccinia virus symptoms

Vaccinia necrosum (gangrenosa), also known as progressive vaccinia, is the most severe complication of vaccinia inoculation. Vaccinia necrosum is due to the accidental or inadvertent administration of vaccinia virus to immunocompromised individuals. Exposure can be due to either direct vaccination or contact with a recently vaccinated individual. The initial site of entry results in a typical-appearing vaccinia lesion that progresses because of the lack of local or systemic immunity. The lesion may progress for months, and secondary lesions can develop elsewhere on the body. Live vaccinia particles can be isolated easily from any of the lesions. The infection is more common in young children with unsuspected immune deficiency disorders and is generally fatal. The condition is rare, severe, and often lethal. Treatment with vaccinia immune globulin, a pooled aggregate of vaccinia-specific antibodies, can be life-saving if administered early.

Eczema vaccinatum occurs in patients with a history of eczema, who are unusually susceptible to infection with both the herpes simplex virus and vaccinia virus. The virus multiplies rapidly in eczematous skin. Lesions begin to appear at distant sites as the virus spreads throughout the body. The lesions are similar in appearance to smallpox but can be differentiated by a less regular pattern. As the infection progresses, however, few areas may be free of lesions. Culture assays of the virus are necessary to differentiate eczema vaccinatum from herpes infection. The disease has a 30% mortality rate, largely in infants. Treatment with vaccinia immune globulin has some limited benefit.

Accidental/inadvertent vaccinia infection occurs when the vaccinia virus spreads from one part of the body to another. Infections of both the nose and the eyelid are most common, although other sites (eg, the perineum) can also be involved. Contamination occurs when the patient transfers the virus from a recently vaccinated site on the patient or on a vaccinated contact. Although not generally serious in people with healthy immune systems, the infection can spread from the eyelid to the cornea, resulting in permanent damage.

When transmission results from sexual contact with a vaccinated individual, painful vulvar ulcers and/or edema may develop 9. These lesions may be accompanied by lymphadenopathy and, in some cases, pruritus and new vaginal discharge.

Erythematous rash occurs 4-17 days after vaccination and usually lasts approximately 10 days. The rash may have an appearance similar to the typical rash of roseola or erythema multiforme. The cause of the rash is not known, and full recovery without treatment is common.

Generalized vaccinia occurs in immunocompetent individuals for unknown reasons. After vaccination and before protective immunity develops, the virus spreads hematogenously and travels to ectopic sites, where it multiplies in epidermal cells. Lesions similar to the primary vaccination site appear on the skin throughout the body. The irregularity of the lesions and the healthy immune system of affected patients differentiate this disease from erythematous rash and accidental vaccinia. Recovery generally occurs without specific intervention. If symptoms last for more than 15 days, vaccinia immune globulin can be administered.

Generalized vaccinia is a rarely reported complication of vaccinia virus vaccination, and true generalized vaccinia may be even less common because of more strict definitions. Appropriately screened individuals considering vaccinia virus vaccination may be reassured that most exanthemata after vaccination are benign.

Fetal vaccinia is a rare but often lethal condition that manifests as multiple skin lesions, including macules, papules, vesicles, pustules, scars, ulcers or areas of maceration, and epidermolysis of blisters of bullae in a fetus.

CNS complications

Postinfection encephalitis is a rare and serious complication of infection with several viruses, including measles and vaccinia. The relationship of the vaccinia virus to encephalitis is unknown. The encephalitis that develops in children younger than 2 years is characterized by an incubation period of 6-10 days and is associated with degenerative changes in ganglion cells, perivascular hemorrhage, and generalized hyperemia of the brain. Symptoms are the same as those associated with general encephalitis, including intracranial pressure, myelitis, convulsions, and muscular paralysis.

A second form of disease develops in older children and adults. This is characterized by an incubation period of 11-15 days and is associated with signs of an allergic response with perivascular demyelination.

CNS complications are rare in infants younger than 6 months and in patients who are revaccinated with vaccinia virus. Although the etiology is unknown, administration of vaccinia immune globulin along with the primary vaccination in army recruits showed significant reduction in the incidence of this complication. Treatment is generally supportive and may include steroids for cerebral edema.

Cardiac complications

These include dilated cardiomyopathy, myocarditis and/or pericarditis, and ischemic heart disease. Cardiac deferral criteria include a history of underlying cardiac disease and at least 3 of 5 of the following major risk factors for atherosclerotic heart disease: hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, smoking, or a history of heart disease in a first-degree relative younger than 50 years.

Vaccinia virus diagnosis

The diagnosis of vaccinia virus complications is usually straightforward and depends on obtaining the history of recent vaccinia virus exposure by vaccination or contact with a vaccinated individual. A careful workup for immune deficiency should be considered in patients who do not promptly improve.

Consultation with a dermatologist may be helpful when the diagnosis of a skin lesion is in doubt. Patients who present with skin manifestations usually have live viral particles replicating in the dermal lesions. The presence of vaccinia virus can be confirmed by obtaining a biopsy of the skin lesion and examination through microscopy, plaque titer assay, Western blot, and polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis.

The diagnosis of central nervous system (CNS) complications is more difficult because the signs and symptoms are nonspecific. Although rare, postvaccinial encephalitis should be considered in any patient with neurologic symptoms developing 1-2 weeks after exposure to live vaccinia virus. Vaccinia virus has not been isolated from cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) of patients with encephalitis, and CSF analysis usually produces normal results, except for increased pressure; however, CSF analysis may be indicated to exclude other causes of encephalitis.

Vaccinia virus treatment

Suspected cases of vaccinia-related complications should be treated in consultation with an expert in infectious diseases and poxvirus virology. Treatment for the complications associated with vaccinia virus is supportive.

Vaccinia immune globulin (VIG) may be helpful in selected patients, such as those with generalized vaccinia and eczema vaccinatum or those at high risk for developing complications following vaccination with vaccinia. Vaccinia immune globulin is less successful when used for treatment of progressive vaccinia and CNS complications.

Vaccinia immune globulin was developed from pooled sera collected from vaccinated patients in the 1960s and is available from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in Atlanta, GA.

Vaccinia immune globulin is contraindicated in patients with allergies to vaccinia immune globulin or sensitivity to human pooled serum.

The first drug for the treatment of smallpox, tecovirimat, was approved in July 2018 should smallpox ever be used as a bioweapon. Tecovirimat is an antiviral that inhibits the activity of the orthopoxvirus VP37 protein. The effectiveness of tecovirimat against smallpox was established by studies in animals infected with viruses closely related to variola virus, which demonstrated higher survival rates compared with those of placebo. The safety of tecovirimat was demonstrated in 359 healthy human volunteers, in whom the most frequently reported adverse effects included headache, nausea, and abdominal pain 10.

Cidofovir and adefovir are being investigated to evaluate the clinical effect and outcomes as a secondary treatment of vaccinia-related complications that do not respond to vaccinia immune globulin treatment. An oral form of this drug is currently under development.

To obtain tecovirimat, clinicians should contact the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Emergency Operations Center, , which will coordinate shipment with the US government’s Strategic National Stockpile.

The antiviral agent cidofovir is available from the Strategic National Stockpile as an investigational agent for treatment of smallpox. Cidofovir is approved in the United States for CMV retinitis.

- Guo ZS, Lu B, Guo Z, et al. Vaccinia virus-mediated cancer immunotherapy: cancer vaccines and oncolytics. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7(1):6. Published 2019 Jan 9. doi:10.1186/s40425-018-0495-7 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6325819[↩][↩]

- Vaccinia. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/231773-overview[↩]

- Smallpox Vaccine Basics. https://www.cdc.gov/smallpox/vaccine-basics/index.html[↩]

- MacLeod DT, Nakatsuji T, Wang Z, di Nardo A, Gallo RL. Vaccinia Virus Binds to the Scavenger Receptor MARCO on the Surface of Keratinocytes. J Invest Dermatol. 2014 Aug 4.[↩]

- Petersen BW, Harms TJ, Reynolds MG, Harrison LH. Use of Vaccinia Virus Smallpox Vaccine in Laboratory and Health Care Personnel at Risk for Occupational Exposure to Orthopoxviruses – Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016 Mar 18. 65 (10):257-62.[↩]

- Couch RB, Winokur P, Edwards KM, Black S, Atmar RL, Stapleton JT, et al. Reducing the dose of smallpox vaccine reduces vaccine-associated morbidity without reducing vaccination success rates or immune responses. J Infect Dis. 2007 Mar 15. 195(6):826-32.[↩]

- Rimmelzwaan GF, Sutter G. Candidate influenza vaccines based on recombinant modified vaccinia virus Ankara. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2009 Apr. 8(4):447-54.[↩]

- Tykodi SS, Thompson JA. Development of modified vaccinia Ankara-5T4 as specific immunotherapy for advanced human cancer. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2008 Dec. 8(12):1947-53.[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Vulvar vaccinia infection after sexual contact with a military smallpox vaccinee–Alaska, 2006. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2007 May 4. 56(17):417-9.[↩]

- Grosenbach DW, Honeychurch K, Rose EA, Chinsangaram J, Frimm A, Maiti B, et al. Oral Tecovirimat for the Treatment of Smallpox. N Engl J Med. 2018 Jul 5. 379 (1):44-53.[↩]