What is vaginal hysterectomy

Vaginal hysterectomy is surgery to remove a woman’s womb (uterus) through the vagina. The uterus is a hollow muscular organ that nourishes the developing baby during pregnancy. Vaginal hysterectomy is the method of choice for removal of the uterus in patients with benign gynecological diseases 1. For women of advanced age and small uterus size, the vaginal hysterectomy procedure has some advantages over abdominal hysterectomy procedure, including less complications, shorter hospital stay, and faster recovery 2. According to the surveillance data from 1995-1996 in the UK, most hysterectomies in the UK are abdominal (70–90%) with only 10–30% performed vaginally and less than 5% laparoscopically 3. A recent report in Denmark shows that the use of vaginal hysterectomy increases from 12 to 34%, accompanied with a decrease in the use of abdominal hysterectomy 4. However, vaginal hysterectomy is contraindicated in patients with large uterine size 5, because the vaginal route offers relatively limited space for surgical procedure. Therefore, surgeons have greater confidence in operating through the abdominal route if adequate surgical hemostasis is maintained.

Vaginal hysterectomy is usually performed under a general anesthetic. Vaginal hysterectomy usually takes about 45 minutes.

Your gynecologist will make a cut around your cervix at the top of your vagina so they can remove your womb and cervix.

They will usually stitch the support ligaments of your womb to the top of your vagina to reduce the risk of a future prolapse.

After a hysterectomy, you’ll no longer have periods or be able to get pregnant.

If you had your ovaries removed but hadn’t reached menopause, you’ll begin menopause immediately after surgery. You might have symptoms such as vaginal dryness, hot flashes and night sweats. Your doctor can recommend medications for these symptoms. He or she might recommend hormone replacement even if you don’t have symptoms.

If your ovaries weren’t removed during surgery — and you still had periods before your surgery — your ovaries continue producing hormones and eggs until you reach natural menopause.

Hysterectomy is currently one of the most common gynecological surgical procedures 6. In the United States, hysterectomy is second to Cesarean delivery as the most frequently performed major surgical procedure for women of the reproductive age. Approximately one in three women has undergone a hysterectomy by age 60, with approximately 600 000 hysterectomies performed annually in the United States 7.

The route of hysterectomy is guided by the surgical indication for hysterectomy, patient anatomy, data that support the selected procedure, informed patient preference, and the surgeon’s expertise 8. The common indications for traditional vaginal hysterectomy include good uterine activity, volume of uterus equivalent to less than 12 weeks’ gestation, no history of pelvic surgery, normal adnexa, wide maternal pelvis, and no other anesthetic or surgical contraindications. In this study 9, vaginal hysterectomy was performed in patients with uterine size equivalent to 8-16 weeks, and was associated with less operation time, less intraoperative blood loss and better postoperative outcomes compared with abdominal hysterectomy, suggesting that vaginal hysterectomy is an effective treatment for patients with benign gynecological diseases.

In addition, Mistrangelo et al. 10 reported that vaginal hysterectomy was safe and effective in cases of greater uterine weight or volume. Guvenal et al. 11 found that vaginal hysterectomy could be performed with less morbidity, even in patients with a large, immobile uterus and previous pelvic surgery. Falcone et al 12 have confirmed the success of the vaginal approach in patients with these characteristics. Rates of urethral and bladder injuries at the time of vaginal hysterectomy were 0.88% and 1.76%, respectively 13. Consistent with this, in a recent large case series, the incidence of bowel injury was low in vaginal hysterectomy patients 13. Furthermore, conversion rates from the vaginal to abdominal approach have been reported to be of 0.4% in a retrospective review of 220 patients 14. In this study 9, no intraoperative complications occurred in patients of the vaginal hysterectomy group, and no vaginal approach was converted to an abdominal approach. Taken together, all these studies indicate that vaginal hysterectomy is a safe and effective surgical treatment for benign gynaecological diseases.

There are different types of hysterectomy:

- Total hysterectomy: The entire uterus, including the cervix, is removed.

- Supracervical (also called subtotal or partial) hysterectomy: The upper part of the uterus is removed, but the cervix is left in place. This type of hysterectomy can only be performed laparoscopically or abdominally.

- Radical hysterectomy: This is a total hysterectomy that also includes removal of structures around the uterus. It may be recommended if cancer is diagnosed or suspected.

If needed, the ovaries and fallopian tubes may be removed if they are abnormal (for example, they are affected by endometriosis). This is called salpingo-oophorectomy if both tubes and ovaries are removed; salpingectomy if just the fallopian tubes are removed; and oophorectomy if just the ovaries are removed. Your surgeon may not know whether the ovaries and fallopian tubes will be removed until the time of surgery. Women at risk of ovarian cancer or breast cancer can choose to have both ovaries removed even if these organs are healthy in order to reduce their risk of cancer. This is called a risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy.Removing the fallopian tubes (but not the ovaries) at the time of hysterectomy also may be an option for women who do not have cancer. This procedure is called opportunistic salpingectomy. It may help prevent ovarian cancer. Talk with your surgeon about the possible benefits of removing your fallopian tubes at the time of your surgery.

Vaginal hysterectomy indications

Vaginal hysterectomy treats various gynecological problems, including:

- Fibroids. Many hysterectomies are done to permanently treat these benign tumors in your uterus that can cause persistent bleeding, anemia, pelvic pain, pain during intercourse and bladder pressure. For large fibroids, you might need surgery that removes your uterus through an incision in your lower abdomen (abdominal hysterectomy).

- Endometriosis. This occurs when the tissue lining your uterus (endometrium) grows outside the uterus, involving the ovaries, fallopian tubes or other organs. Most women with endometriosis have a laparoscopic or robotic hysterectomy or abdominal hysterectomy, but sometimes a vaginal hysterectomy is possible.

- Adenomyosis. This occurs when the tissue that normally lines the uterus grows into the uterine wall. An enlarged uterus and painful, heavy periods result.

- Gynecological cancer. If you have cancer of the uterus, cervix, endometrium or ovaries, or precancerous changes, your doctor might recommend a hysterectomy. Most often, treatment for ovarian cancer involves an abdominal hysterectomy, but sometimes vaginal hysterectomy is appropriate for women with cervical or endometrial cancer.

- Uterine prolapse. When pelvic supporting tissues and ligaments weaken or stretch out, the uterus can sag into the vagina, causing urine leakage, pelvic pressure or difficulty with bowel movements. Removing the uterus and repairing supportive tissues might relieve those symptoms.

- Abnormal uterine bleeding. When medication or a less invasive surgical procedure doesn’t control irregular, heavy or very long periods, hysterectomy may be needed.

- Chronic pelvic pain. If your pain is clearly caused by a uterine condition, hysterectomy might help, but only as a last resort. Chronic pelvic pain can have several causes, so an accurate diagnosis of the cause is critical before having a hysterectomy.

For most of these conditions — with the possible exception of cancer — hysterectomy is just one of several treatment options. You might not need to consider hysterectomy if medications or less invasive gynecological procedures manage your symptoms.

You cannot become pregnant after a hysterectomy. If you’re not sure that you’re ready to give up your fertility, explore other treatments.

Vaginal hysterectomy contraindications

There are very few absolute contraindications for vaginal hysterectomy (e.g., pregnancy, cancer). However, there are some factors that may influence the surgeon’s choice of a route for hysterectomy, including the following:

- Surgeon training and experience

- Accessibility of the uterus

- Extent of extrauterine disease

- Size and shape of the uterus

- Need for concurrent procedures

- Patient preference

There are some relative contraindications to vaginal hysterectomy, such as the following:

- Enlarged uterus

- Nulliparity

- Narrow vagina

- Narrow pubic arch (< 90º)

- Immobile uterus

Other possible concerns that may militate against vaginal hysterectomy include extrauterine disease (eg, adnexal pathology), severe endometriosis, adhesions, and an indication for salpingo-oophorectomy. When these concerns arise, many surgeons choose to visualize the pelvis laparoscopically before deciding on the route for hysterectomy. The decision to perform a salpingo-oophorectomy should not be influenced by the chosen route for hysterectomy and is not a contraindication for vaginal hysterectomy 15.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists made the following recommendations on choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease 16:

- Vaginal hysterectomy is the approach of choice whenever feasible.

- Laparoscopic hysterectomy is a preferable alternative to open abdominal hysterectomy for those patients in whom a vaginal hysterectomy is not indicated or feasible.

- The surgeon should account for clinical factors to determine the best route of hysterectomy for each individual patient.

- The size and shape of the vagina and uterus; accessibility to the uterus (eg, descensus, pelvic adhesions); extent of extrauterine disease; the need for concurrent procedures; surgeon training and experience; average case volume; available hospital technology, devices, and support; whether the case is emergent or scheduled, and patient preference can all influence the route of hysterectomy.

- A discussion with the patient should take place on the route of hysterectomy and advantages and disadvantages of each approach.

- Opportunistic salpingectomy usually can be safely accomplished at the time of vaginal hysterectomy.

- The role of robotic assistance for execution of laparoscopic hysterectomy has not been clearly determined and more studies are needed to determine clinical use.

In practice, most vaginal surgeons individualize the choice of a hysterectomy route. Many nulliparous women and many women who have undergone cesarean delivery do in fact have sufficient vaginal capacity to allow a vaginal hysterectomy. As long as the surgeon can obtain adequate access for division of the uterosacral and cardinal ligaments, the uterus can be mobilized sufficiently to allow vaginal extraction.

Even when the uterus is enlarged, vaginal hysterectomy often can be accomplished safely by means of morcellation, uterine bisection, wedge debulking, or intramyometrial coring 15.

Vaginal hysterectomy procedure

Once the patient has been properly positioned, a weighted speculum is placed into the posterior vagina, and a right-angle retractor is positioned anterior to the cervix while the anterior and posterior lips of the cervix are grasped with a single- or double-toothed tenaculum. Some surgeons inject vasopressin (10-20 U in 50 mL of saline) or lidocaine 0.5% into the cervical, paracervical, and submucosal tissues to help identify tissue planes and reduce blood loss, but these agents are not required.

Vaginal hysterectomy preparation

As with any surgery, it’s normal to feel nervous about having a hysterectomy. Here’s what you can do to prepare:

- Gather information. Before the surgery, get all the information you need to feel confident about it. Ask your doctor and surgeon questions.

- Follow your doctor’s instructions about medication. Find out whether you should take your usual medications in the days before your hysterectomy. Be sure to tell your doctor about over-the-counter medications, dietary supplements or herbal preparations that you take.

- Discuss anesthesia. You might prefer general anesthesia, which makes you unconscious during surgery, but regional anesthesia — also called spinal block or epidural block — might be an option. During a vaginal hysterectomy, regional anesthesia will block the feelings in the lower half of your body. With general anesthesia, you’ll be asleep.

- Arrange for help. Although you’re likely to recover sooner after a vaginal hysterectomy than after an abdominal one, it still takes time. Ask someone to help you out at home for the first week or so.

Talk with your doctor about what to expect during and after a vaginal hysterectomy, including physical and emotional effects.

During the vaginal hysterectomy procedure

You’ll lie on your back, in a position similar to the one you’re in for a Pap test. You might have a urinary catheter inserted to empty your bladder. A member of your surgical team will clean the surgical area with a sterile solution before surgery.

To perform the vaginal hysterectomy:

- Your surgeon makes an incision inside your vagina to get to the uterus

- Using long instruments, your surgeon clamps the uterine blood vessels and separates your uterus from the connective tissue, ovaries and fallopian tubes

- Your uterus is removed through the vaginal opening, and absorbable stitches are used to control any bleeding inside the pelvis

Except in cases of suspected uterine cancer, the surgeon might cut an enlarged uterus into smaller pieces and remove it in sections (morcellation).

Laparoscopic or robotic hysterectomy

You might be a candidate for a laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy or robotic hysterectomy. Both procedures allow your surgeon to remove the uterus vaginally while being able to see your pelvic organs through a slender viewing instrument called a laparoscope.

Your surgeon performs most of the procedure through small abdominal incisions aided by long, thin surgical instruments inserted through the incisions. Your surgeon then removes the uterus through an incision made in your vagina.

Your surgeon might recommend laparoscopically assisted vaginal hysterectomy or robotic hysterectomy if you have scar tissue on your pelvic organs from prior surgeries or from endometriosis.

Vaginal hysterectomy steps

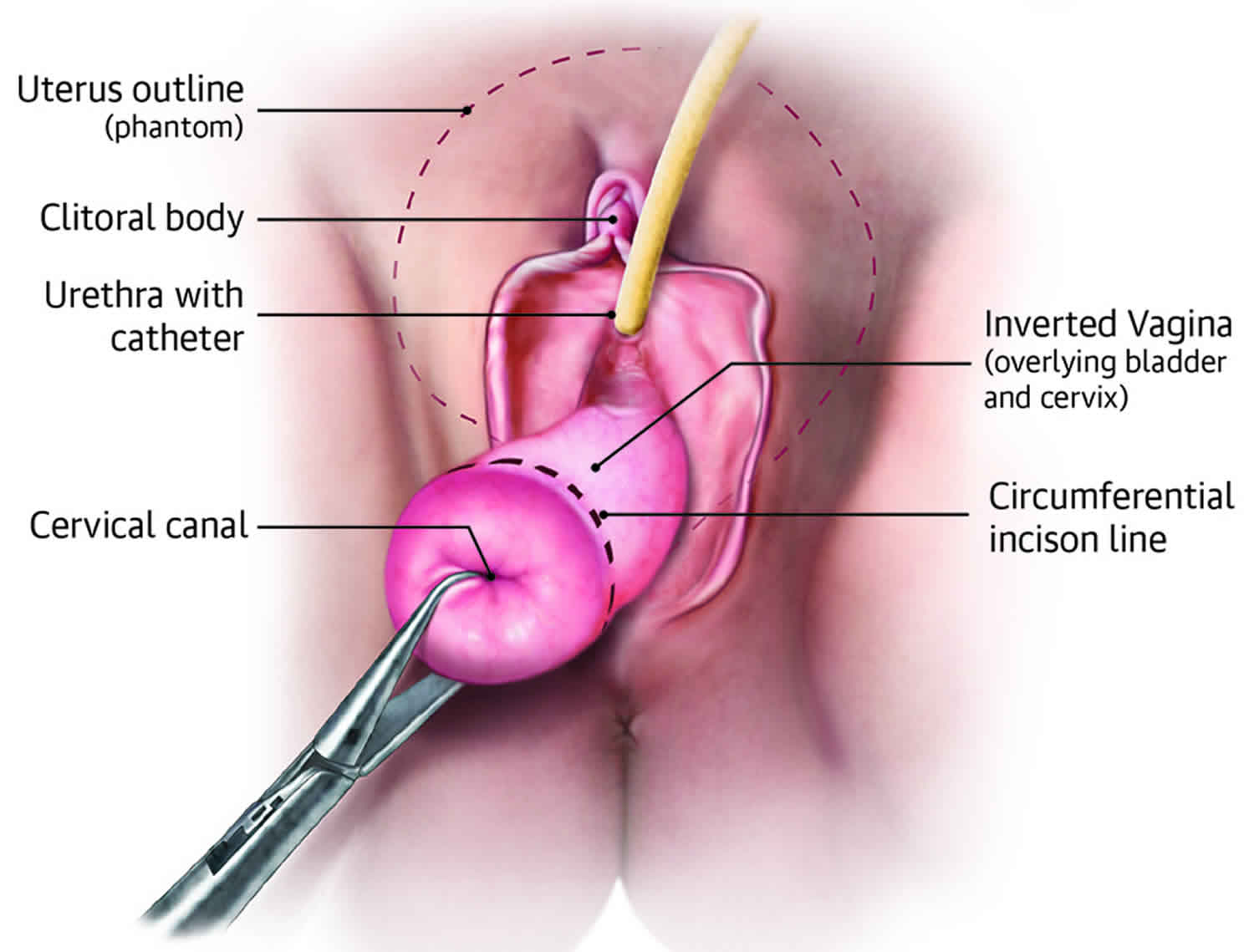

Vaginal incision and opening of posterior peritoneum

The initial vaginal incision is made circumferentially, beginning at the level of the vaginal rugae through the full thickness of the vagina, just below the bladder reflection—not on the cervix (see the image below). If an incidental cystotomy occurs, the vaginal hysterectomy should be completed before the bladder is repaired. The vaginal epithelium is dissected bluntly or sharply to the underlying tissue with an open sponge over the index finger and Mayo scissors.

The posterior peritoneum is then identified where rugae are not present and where the uterosacral ligaments join the cervix. The peritoneum is grasped with tissue forceps and incised with Mayo scissors in a generous bite and a Steiner-Anvard weighted speculum is inserted into the posterior cul-de-sac.

Division and ligation of uterosacral ligaments

The uterosacral ligaments are identified and clamped, with the tip of the clamp incorporating the lower portion of the cardinal ligaments. The clamp is placed perpendicular to the uterine axis, and the pedicle is cut so that approximately 0.5 cm of tissue is distal to the clamp. A transfixion suture is placed at the tip of the clamp and tied. This suture may be held with a hemostat to facilitate location of any bleeding at the completion of the procedure and to aid in vaginal closure.

Opening of anterior peritoneum

Attention is then directed to opening the anterior peritoneum. The anterior peritoneal fold appears as a crescent-shaped line. The peritoneal reflection is grasped with tissue forceps, tented, and opened with scissors that have their tips pointed toward the uterus. A Heaney or Deaver retractor is placed into this space to protect the bladder and to facilitate visualization of the abdominal contents.

If the peritoneal reflection is not readily identified, one can wait to make the entry, as long as the bladder has been safely advanced cranially. A Deaver or Heaney retractor is placed in the midline to keep the bladder out of the operative field. Blunt or sharp advancement of the bladder should continue before each clamp placement until the vesicovaginal space is entered. Once this space is entered, the Heaney or Deaver retractor is placed into the peritoneal cavity.

Division and ligation of cardinal ligaments

Next, the cardinal ligaments are identified, clamped, cut, and suture-ligated in a manner similar to that previously described for the uterosacral ligaments. Alternatively, newer electrocauterization devices (eg, LigaSure; Covidien, Boulder, CO) can be used in vessels up to 7 mm in diameter to accomplish the same task.

The uterine vessels are then clamped in such a way as to incorporate the anterior and posterior leaves of the visceral peritoneum (an important step). A single-clamp technique reduces the risk of ureteral injury.

Delivery of surgical specimen

The uterine fundus is delivered posteriorly by placing a tenaculum or towel clip on the uterine fundus in successive bites. The utero-ovarian ligament is identified with the surgeon’s finger, then clamped and cut. The pedicles are double-ligated, first with a suture tie and then with a suture ligature medial to the first tie. A hemostat is placed on the second suture to assist in the identification of any bleeding.

If the adnexa are to be removed, traction is placed on the ovary by grasping it with a Babcock clamp. A Heaney clamp is placed across the infundibulopelvic ligament, and the ovary and tube are excised. Both a suture tie and a transfixion suture ligature are placed on this pedicle.

Management of enlarged uterus

For enlarged uteri, the following techniques may be employed to facilitate removal of the uterus: morcellation, intramyometrial coring, uterine bisection, and wedge debulking.

Morcellation can be used in cases involving uterine enlargement, uterine fixation, or limited vaginal exposure. It should not be performed if the uterine arteries cannot be secured or if malignancy is suspected.

Intramyometrial coring is accomplished by circumferentially incising the outer myometrium beneath the uterine serosa with a scalpel while placing the cervix on traction. The incision should be kept as close to the uterine serosa as possible. The enlarged uterus is delivered as an elongated mass inverting the uterine fundus.

Uterine bisection is performed by cutting the cervix and the uterine fundus in the sagittal plane. This technique is often combined with myomectomy or wedge morcellation to reduce the bulk of the uterine halves so that the tubo-ovarian vessels can be ligated.

Completion and closure

A sponge-stick or laparotomy pad is placed into the peritoneal cavity to allow the surgeon to visualize each of the pedicles and confirm that hemostasis is adequate. If any bleeding points are identified, a suture is used to ligate the bleeding vessel under direct vision. The pelvic peritoneum is left open.

Finally, the vaginal epithelium is reapproximated either vertically or horizontally with either a continuous suture or a series of interrupted sutures. These sutures are placed through the full thickness of the vaginal epithelium, with care taken to ensure that the bladder is not entered.

Culdoplasty for prevention of enterocele

A culdoplasty is generally recommended to reduce the risk of subsequent enterocele formation and potential vaginal vault prolapse. The 2 methods commonly described are the Moschcowitz repair (ie, closing the cul-de-sac and bringing the uterosacral-cardinal complex together in the midline) and the McCall culdoplasty (ie, obliterating the cul-de-sac, plicating the uterosacral-cardinal complex, and elevating any redundant posterior vaginal apex). There is some evidence to suggest that the McCall procedure is superior in preventing enterocele.

In this procedure, an absorbable suture is placed through the full thickness of the posterior vaginal wall at the apex of what will be the vaginal vault. This suture is passed through the left uterosacral ligament pedicle, the posterior peritoneum, and the right uterosacral ligament and completed by being passed from the inside to the outside at the same point where it was begun. The suture is then tied, thus approximating the uterosacral ligaments and the posterior peritoneum. It is not necessary to use a vaginal pack or leave a bladder catheter in place.

Vaginal hysterectomy complications

Although vaginal hysterectomy is generally safe, any surgery has risks. Risks of vaginal hysterectomy include:

- Heavy bleeding

- Blood clots in the legs or lungs

- Infection

- Damage to surrounding organs

- Adverse reaction to anesthetic

Severe endometriosis or scar tissue (pelvic adhesions) might force your surgeon to switch from vaginal hysterectomy to laparoscopic or abdominal hysterectomy during the surgery.

General complications

- pain

- feeling or being sick

- bleeding

- infection of the surgical site (wound)

- blood clots

Specific complications

- pelvic infection or abscess

- damage to structures close to your womb

- developing an abnormal connection

- conversion to an abdominal hysterectomy

- developing a collection of blood

- vaginal cuff dehiscence

Long-term problems

- prolapse

- continued pain

- tissues can join together in an abnormal way

- stress incontinence

- feelings of loss (a hysterectomy will make you infertile)

- menopause, even if your ovaries are not removed

The primary intraoperative complications are visceral injury and hemorrhage. Reported rates of hemorrhage range from 1.4% to 2.6%, whereas reported rates of ureteral and bladder injury are 0.88% and 1.76%, respectively 17.

The most common postoperative complication is pelvic infection. Febrile morbidity occurs in approximately 15% of women who undergo vaginal hysterectomy and can be reduced by means of prophylactic antibiotics. Infections after vaginal hysterectomy include vaginal cuff cellulitis, pelvic cellulitis, and pelvic abscess. These infections occur in approximately 4% of women 18.

Vaginal hysterectomy recovery

After surgery, you’ll be in a recovery room for one to two hours and in the hospital overnight.

Recovering from a hysterectomy takes time. Most women stay in the hospital one to two days after surgery. Some doctors may send you home the same day of your surgery. Some women stay in the hospital longer, often when the hysterectomy is done because of cancer.

You’ll take medication for pain. Your health care team will encourage you to get up and move as soon as possible after your hysterectomy. This includes going to the bathroom on your own. However, you may have to pee through a thin tube called a catheter for one or two days after your surgery.

It’s normal to have bloody vaginal discharge for several days to weeks after a hysterectomy, so you’ll need to wear sanitary pads.

How you’ll feel physically

Recovery after vaginal hysterectomy is shorter and less painful than it is after an abdominal hysterectomy. A full recovery might take three to four weeks.

Even if you feel recovered, don’t lift anything heavy — more than 20 pounds (9.1 kilograms) — or have vaginal intercourse until six weeks after surgery.

Contact your doctor if pain worsens or if you develop nausea, vomiting or bleeding that’s heavier than a menstrual period.

What changes can I expect after a hysterectomy?

Hysterectomy is a major surgery, so recovery can take a few weeks. But for most women, the biggest change is a better quality of life. You should have relief from the symptoms that made the surgery necessary.

Other changes that you may experience after a hysterectomy include:

- Menopause. You will no longer have periods. If your ovaries are removed during the hysterectomy, you may have other menopause symptoms.

- Change in sexual feelings. Some women have vaginal dryness or less interest in sex after a hysterectomy, especially if the ovaries are removed.

- Increased risk for other health problems. If both ovaries are removed, this may put you at higher risk for certain conditions such as: bone loss, heart disease, and urinary incontinence (leaking of urine). Talk to your doctor about how to prevent these problems.

- Sense of loss. Some women may feel grief or depression over the loss of fertility or the change in their bodies. Talk to your doctor if you have symptoms of depression, including feelings of sadness, a loss of interest in food or things you once enjoyed, or less energy, that last longer than a few weeks after your surgery.

Feeling low after a hysterectomy

Having your uterus removed can cause you to have feelings of loss or sadness. However, these feelings should pass.

You may find it helps to focus on your recovery – eating healthily, getting some exercise (your doctor will tell you how much activity you should aim for) and talking to your partner or friends about how you’re feeling.

If you’re finding it hard to cope with these emotions, talk to your doctor. You may be able to have counselling to help you work through your feelings.

How you’ll feel emotionally

After a hysterectomy, you might feel relief because you no longer have heavy bleeding or pelvic pain.

For most women, there’s no change in sexual function after hysterectomy. But for some women, heightened sexual satisfaction occurs after hysterectomy — perhaps because they no longer have pain during intercourse.

You might feel a sense of loss and grief after hysterectomy, which is normal. Or you might have depression related to the loss of your fertility, especially if you’re young and hoped for a future pregnancy. If sadness or negative feelings interfere with your enjoyment of everyday life, talk to your doctor.

Sex after hysterectomy

How a hysterectomy might affect your sex life, how long you should wait before having sex again and how to cope with issues such as vaginal dryness.

It takes time to get back to normal after an operation, but having a hysterectomy can have a strong emotional impact too, which can affect how you feel about sex.

If you had a good sex life before your hysterectomy, you should be able to return to it without any problems after recovery. Many women report a better sex life after hysterectomy because of relief from pain or heavy vaginal bleeding.

If your hysterectomy causes you to have symptoms of menopause, you may experience vaginal dryness or a lack of interest in sex. Using a water-based lubricant can help with dryness.

If you experience problems with sex after your operation, there is help available. You can talk to your doctor.

How long should you wait before having sex after a hysterectomy?

You will be advised not to have sex for around 4 to 6 weeks after having a hysterectomy. This should allow time for scars to heal and any vaginal discharge or bleeding to stop.

If you don’t feel ready for sex after 6 weeks, don’t worry – different women feel ready at different times.

There are many different types of hysterectomy, which will affect how it is performed and what is removed.

A total hysterectomy is the removal of the uterus (womb) and cervix. If the cervix remains intact, this is a subtotal hysterectomy. Sometimes the ovaries or fallopian tubes are removed as well.

Which organs are removed will depend on your own personal circumstances and the reasons you’re having a hysterectomy.

Bleeding after sex after a hysterectomy

If you notice bleeding after sex after a hysterectomy, see a doctor to find out why it is happening. Your doctor may be able to offer treatment, and can check that everything is healing well.

Do I still need to have Pap tests?

Maybe. You will still need regular Pap tests (or Pap smear) to screen for cervical cancer if you:

- Did not have your cervix removed

- Had a hysterectomy because of cancer or precancer

Ask your doctor what is best for you and how often you should have Pap tests.

Vaginal hysterectomy recovery time

You will usually be able to go home after 1 to 3 days. Rest for 2 weeks and continue to do the exercises that you were shown in hospital. You can usually return to work after 4 to 6 weeks, depending on your type of work.

You should be feeling more or less back to normal after 2 to 3 months.

Regular exercise should help you to return to normal activities as soon as possible. Before you start exercising, ask the healthcare team or your doctor for advice.

References- David-Montefiore E, Rouzier R, Chapron C, Darai E. Surgical routes and complications of hysterectomy for benign disorders: a prospective observational study in French university hospitals. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:260–265

- Johnson N, Barlow D, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006:CD003677

- Maresh MJ, Metcalfe MA, McPherson K, Overton C, Hall V, Hargreaves J, et al. The VALUE national hysterectomy study: description of the patients and their surgery. BJOG. 2002;109(3):302–312

- Nielsen SL, Daugbjerg SB, Gimbel H, Settnes A. Steering Committee of Danish Hysterectomy Database Use of vaginal hysterectomy in Denmark: rates indications and patient characteristics. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2011;90(9):978–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0412.2011.01199.x

- Unger JB. Vaginal hysterectomy for the woman with a moderately enlarged uterus weighing 200 to 700 grams. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:1337–1344

- Wu JM, Wechter ME, Geller EJ, Nguyen TV, Visco AG. Hysterectomy rates in the United States, 2003. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:1091–1095

- Whiteman MK, Hillis SD, Jamieson DJ, Morrow B, Podgornik MN, Brett KM, et al. Inpatient hysterectomy surveillance in the United States, 2000-2004. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198:34.e1–34.e7

- Nieboer TE, Johnson N, Lethaby A, Tavender E, Curr E, Garry R, et al. Surgical approach to hysterectomy for benign gynaecological disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD003677. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003677.pub4

- Chen B, Ren DP, Li JX, Li CD. Comparison of vaginal and abdominal hysterectomy:A prospective non-randomized trial. Pak J Med Sci. 2014;30(4):875–879. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4121717

- Mistrangelo E, Febo G, Ferrero B, Ferrero S, Deltetto F, Camanni M. Safety and efficacy of vaginal hysterectomy in the large uterus with the LigaSure™ bipolar diathermy system. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;199(5):475.e1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2008.03.025

- Guvenal T, Ozsoy AZ, Kilcik MA, Yanik A. The availability of vaginal hysterectomy in benign gynaecological diseases: a prospective, non-randomized trial. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2010;36(4):832–837. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2010.01183.x

- Falcone T, Walters MD. Hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2008;111:753–767

- Ibeanu OA, Chesson RR, Echols KT, Nieves M, Busangu F, Nolan TE. Urinary tract injury during hysterectomy based on universal cystoscopy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113(1):6–10. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818f6219

- Kriplani A, Garg P, Sharma M, Lal S, Agarwal N. A review of total laparoscopic hysterectomy using LigaSure™ uterine artery-sealing device: AIIMS experience. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18(6):825–829. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0034

- ACOG Committee Opinion No. 444: choosing the route of hysterectomy for benign disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2009 Nov. 114(5):1156-8.

- Committee on Gynecologic Practice. Committee Opinion No 701: Choosing the Route of Hysterectomy for Benign Disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2017 Jun. 129 (6):e155-e159.

- Kulkarni MM, Rogers RG. Vaginal hysterectomy for benign disease without prolapse. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010 Mar. 53(1):5-16

- Clarke-Pearson DL, Geller EJ. Complications of hysterectomy. Obstet Gynecol. 2013 Mar. 121(3):654-73