Vasovasostomy

Vasovasostomy is a surgical procedure designed to bypass an obstruction in the male genital tract. Vasovasostomy involves the anastomosis of segments of the vas deferens above and below an obstruction. Vasovasostomy is usually performed to restore fertility. The vast majority of vasovasostomies are performed to reverse a prior vasectomy (vasectomy reversal), but the vasovasostomy procedure is occasionally indicated for repair of an iatrogenic vasal injury secondary to prior surgery (eg, inguinal herniorrhaphy) and occasionally undertaken to relieve pain, such as in postvasectomy pain syndromes.

Azoospermia (the absence of sperm in the ejaculate) can result from an obstructed genital tract or a failure of spermatogenesis in the testicle. Vasovasostomies are indicated for an obstruction at the level of the vas deferens, while vasoepididymostomies are used to treat epididymal obstructions. The site of obstruction can often be discerned by examination of the fluid from the vasal end or from the epididymal tubule. The goal of both procedures is to restore genital tract patency and ultimately to allow conception. These procedures are not indicated for nonobstructive causes of azoospermia.

Primary genital tract obstruction occurs in 7.4% of infertile males who have not undergone a prior vasectomy. While the cause may be multifactorial (eg, including epididymal trauma, infection, congenital hypoplasia of the ductal system), a significant number of these patients are candidates for vasoepididymostomy for restoration of the patency of the seminal tract.

Patients who desire vasovasostomy for vasectomy reversal self-refer for evaluation. All other patients present for an evaluation of infertility after a trial of unprotected intercourse. A careful physical examination suggests the diagnosis of vasal or epididymal obstruction that is amenable to a vasovasostomy or vasoepididymostomy, respectively. Men with a genital tract obstruction have testes of normal size (>20 mL volume or 4 cm length) and consistency. The epididymis feels prominent proximal to a site of obstruction and feels flat (empty) distal to an obstructed tubule. Dilatation of the entire epididymis suggests an obstruction at either the junction of the epididymis with the vas deferens or within the vas deferens itself.

Before a vasovasostomy is done, your doctor will want to confirm that you were fertile before your vasectomy. You can have tests to see whether you have sperm antibodies in your semen before and after vasovasostomy for vasectomy reversal. If there are sperm antibodies in your semen after surgery, your partner is unlikely to become pregnant. In such a case, you may wish to try in vitro fertilization (IVF) with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

Vasovasostomy is most commonly performed under general anesthesia. This provides the most favorable environment for the surgeon to create the optimal microsurgical anastomosis especially if more complicated repairs are necessary 1. Regional anesthetic, such as spinal or epidural anesthesia, can be used if long acting agents are available. Uncomplicated vasovasostomy for vasectomy reversal takes 2 to 4 hours and are often performed under local anesthesia with mild sedation, followed by a few more hours for recovery from the anesthetic. You can expect to go home the same day. Be sure you have someone to drive you home. Anesthesia and pain medicine make it unsafe for you to drive. A broad-spectrum antibiotic is usually administered 30 minutes prior to surgery.

You will be given more specific instructions about recovering from your surgery. They will cover things like diet, wound care, follow-up care, driving, and getting back to your normal routine. Pain may be mild to moderate. You should be able to resume normal activities, including sex, within 3 weeks.

Instructions to wear a scrotal support for 6 weeks are given. Light activity is allowed starting 3 days postoperatively; however, no sports or heavy workload should be undertaken for 2 weeks and sexual activity should be avoided for 3 to 4 weeks total. Semen analyses are collected at 2, 4 and 6 months postoperatively. If azoospermia persists at 6 months, a revision of the vasovasostomy may be necessary.

More recently, new literature has emerged investigating the use of robotic-assisted vasovasostomy with promising results. The handful of studies available, notably from Parekattil et al 2 and Kavoussi 3, have found similar rates of patency compared with microsurgical technique. The potential benefits of the robotic technique vs the microsurgical vasovasostomy appear to be decreased operative time, mildly increased patency rates, and decreased learning curve for the surgeon. Increased cost, as well as decreased magnification compared to the microsurgical technique are the main disadvantages 4.

Vasovasostomy anatomy

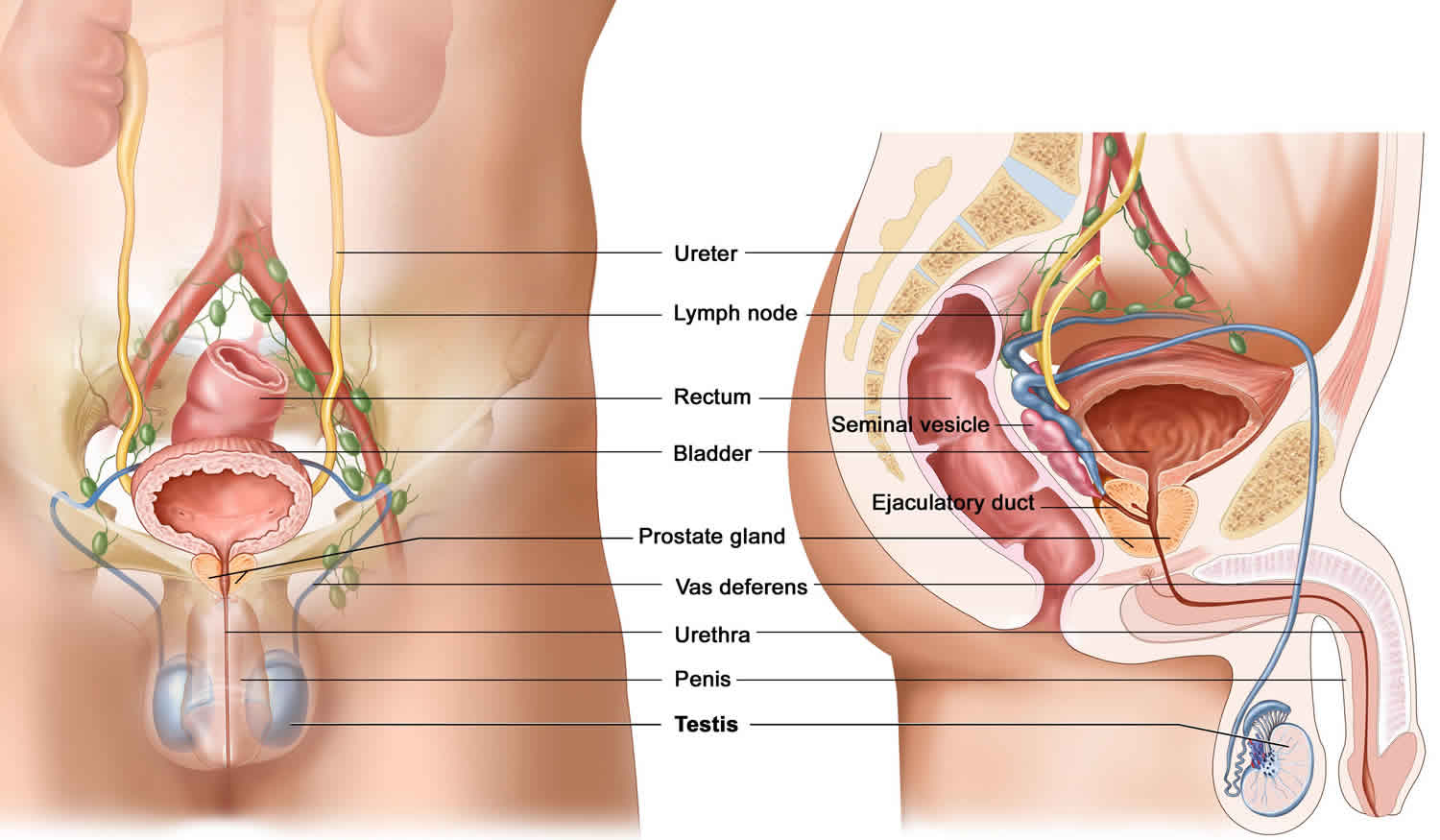

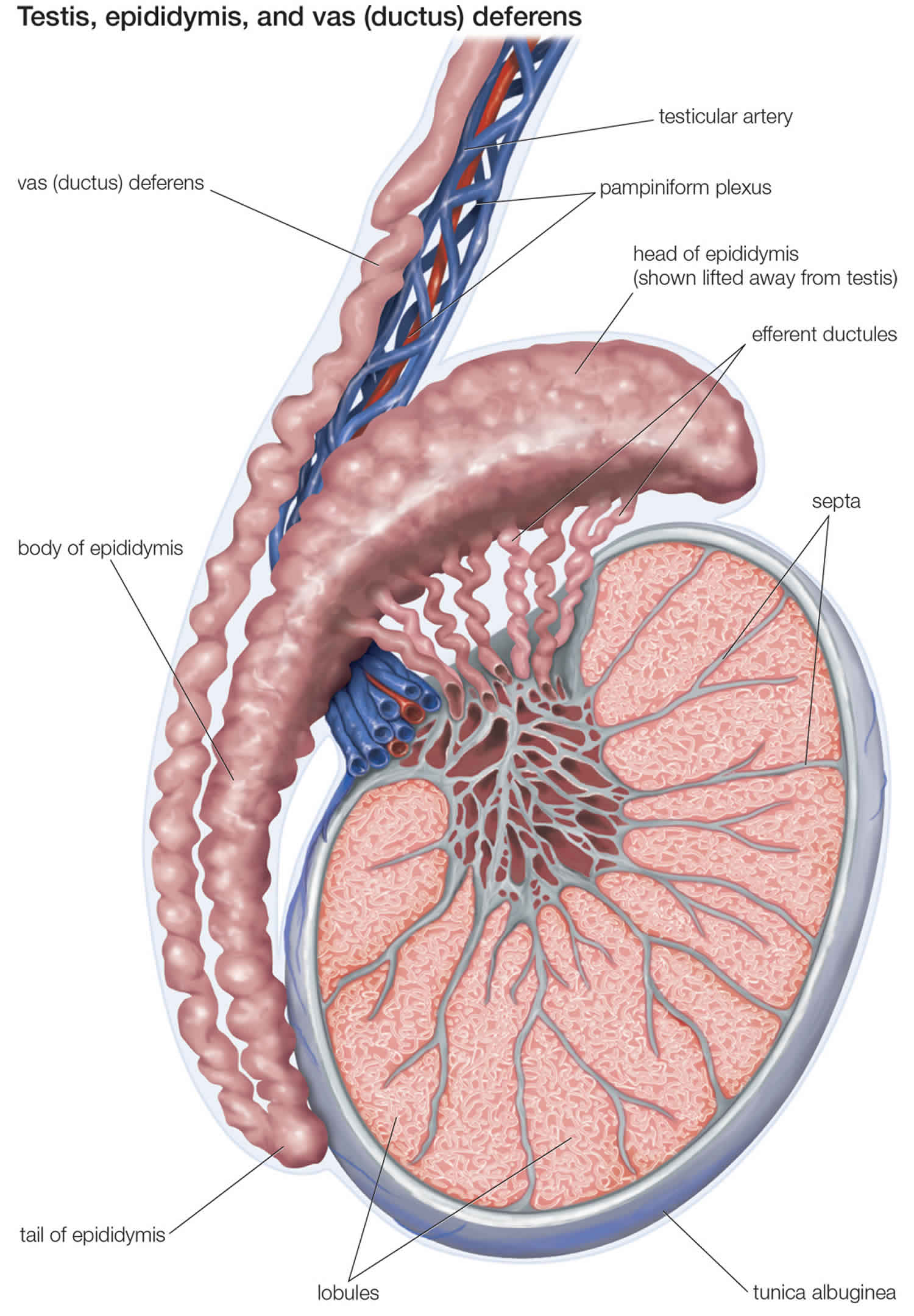

To understand the surgical bypass procedures needed to restore sperm flow, it is important to understand the basic anatomy and physiology of the seminal tract. Sperm is produced and then released into the seminiferous tubules. The sperm transits through the rete testis, efferent ductules, and into the epididymal tubule. See figures 1 to 3.

Epididymis

The epididymis consists of a single, highly convoluted tubule that is covered with tunica vaginalis. By convention, the epididymis is divided into the following anatomic segments: (1) the caput (head), (2) the corpora (body), and (3) the cauda (tail).

The proximal epididymis is involved in sperm maturation, whereas the distal region is the area of sperm storage. Vasoepididymal anastomosis to the more proximal epididymal tubule results in lower pregnancy rates because this bypasses a region of vital importance for sperm development.

Vas deferens

At the terminal end of the epididymis, a thick muscle wall that forms the proximal end of the vas deferens surrounds the tubule. The vas deferens follows the spermatic cord, courses through the inguinal canal, and enters the pelvis via the internal inguinal ring. From the pelvis, the vas travels behind the bladder and joins with the ipsilateral seminal vesicle to form an ejaculatory duct, which enters the prostate posteriorly. Contraction of the muscular wall of the vas deferens serves to propel sperm from the epididymis into the prostatic urethra via the ejaculatory ducts.

Figure 1. Male reproductive organ anatomy

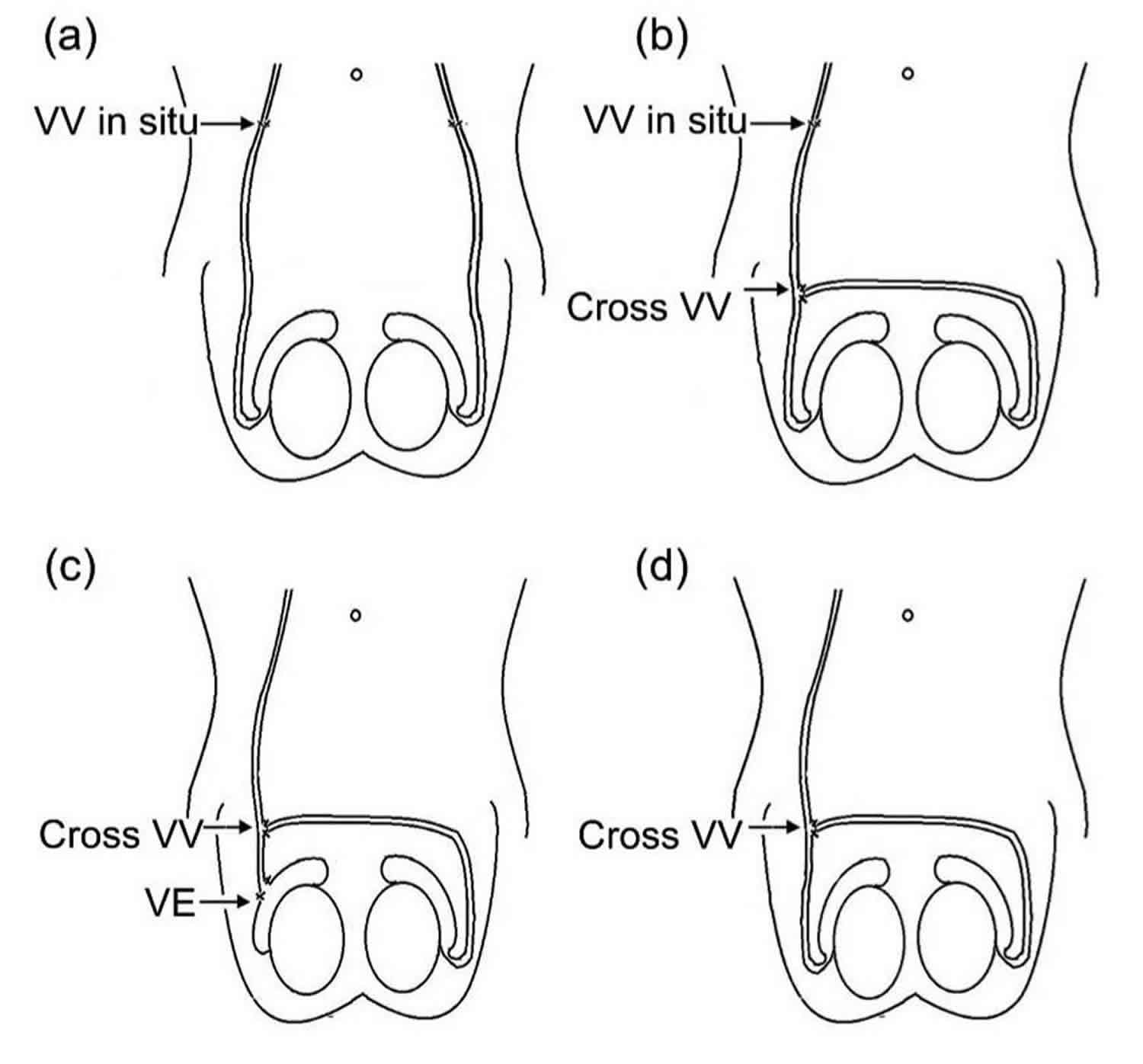

Figure 2. Vasovasostomy

Footnote: Three types of cross vasovasostomy in the scrotum. (a) Vasovasostomy in situ (inguinal region); (b) Cross vasovasostomy (CVV) on the basis of unilateral vasovasostomy in situ; (c) Cross vasovasostomy (CVV) plus unilateral vasoepididymostomy; (d) unilateral cross vasovasostomy

Abbreviations: Vasoepididymostomy (VE); Vasovasostomy (VV)

[Source 5 ]Vasovasostomy uses

The indications for a vasovasostomy include vasectomy reversal and relief of postvasectomy pain syndrome. The latter indication is uncommon and remains of controversial efficacy. Prior to undertaking a vasovasostomy for vasectomy reversal, the female partner should be evaluated by a gynecologist to exclude concurrent female causes of infertility. A vasoepididymostomy is performed for the treatment of a genital tract obstruction at the level of the epididymis.

Both vasal and epididymal obstruction are suggested by azoospermia in the presence of a normal semen volume. Low-volume azoospermia (< 1.5 mL) is more suggestive of ejaculatory duct obstruction than vasal or epididymal obstruction. Patients must have active sperm production in the testes to be considered a candidate for a vasoepididymostomy. For this reason, a testis biopsy is usually performed at the time of or prior to planned reconstruction to document active spermatogenesis. Some surgeons prefer to conduct a biopsy at the time of reconstruction, as this avoids the inevitable scarring that can further complicate reconstruction at a later date.

Vasovasostomy procedure

A 2-cm vertical scrotal incision is made over the prior vasectomy site, and the vas deferens is mobilized. Exposing the epididymis is unnecessary; in fact, this may lead to postoperative adhesions that could further complicate a subsequent vasoepididymostomy. Care is taken to mobilize an adequate vasal length to ensure a tension-free anastomosis and to retain the perivasal vessels to allow for a well-vascularized anastomosis, thus avoiding ischemia with resultant stenosis. The presence of a sperm granuloma has been associated with better grades of sperm quality in the vas but has not been associated with better postoperative results.

The vas deferens is incised above and below the prior vasectomy site. It is then gently dilated with fine forceps and irrigated with a 24F Angiocath to verify patency. Fluid is collected from the proximal vas and microscopically examined for spermatozoa and their components. If spermatozoa or any sperm components are seen, vasovasostomy is performed. If no spermatozoa are seen, vasoepididymostomy is considered. The presence of spermatozoa is associated with the best prognosis for future fertility, although clear fluid without spermatozoa also portends a good outcome. The obstructive interval can also be factored into the decision, as the chance for epididymal obstruction increases with increasing time since the vasectomy. If available, sperm is cryopreserved in case the reconstruction fails.

It is generally accepted that the results of vasovasostomy are better after microsurgical rather than macrosurgical anastomosis, although some surgeons still report favorable results using macrosurgical techniques. Regardless, various methods have been described for performing the vasovasostomy anastomosis, depending on the degree of magnification (loupes, microscope) and the type of procedure (modified 1-layer vs formal 2-layer procedure).

During the procedure, care is taken to prevent thermal damage to the vas, and only bipolar cautery or ophthalmic cautery is used to stop adventitial bleeding. Cautery is never used on the opposing transected ends of the vas deferens.

Follow-up

The patient returns to the office for a wound check in 7 days. A semen analysis is obtained 3 months postsurgery. In patients who have undergone vasoepididymostomy, the anastomosis is often slow to function. In this population, semen analyses are repeated quarterly for a year or until sperm are present.

If no sperm are present by 18 months postsurgery, the operation is considered a failure, and patient is advised about the alternatives (ie, repeat procedure, sperm extraction with in vitro fertilization [IVF], donor insemination, adoption). Failure typically represents an anastomotic scar, which occurs in 3%-12% of patients after vasovasostomy and 21% after vasoepididymostomy.

If the patient develops normal semen concentrations postoperatively and his wife does not conceive, consideration should be given to antisperm antibodies on the surface of the sperm.

Repeat surgical reconstructions with vasoepididymostomies and vasovasostomies can be performed, but these are technically more demanding because of extensive scarring and should be undertaken only by an experienced microsurgeon. With that caveat, the success rates for these procedures are comparable to those of initial reconstructions.

Vasovasostomy risks

Risks of vasovasostomy include:

- Infection at the site of surgery.

- Fluid buildup in the scrotum (hydrocele) that may require draining.

- Injury to the arteries or nerves in the scrotum.

Hematoma, infection, and testicular atrophy are the main complications of vasovasostomy. Formation of a scrotal hematoma remains the most common postoperative complication. A series of 2500 operations had seven occurrences of scrotal hematoma 6. None of these required surgical intervention and no wound infections were encountered. If a scrotal hematoma does form, it generally resolves in 6–12 weeks with conservative treatment. Scrotal hematoma is largely preventable by careful attention to hemostasis throughout the dissection. Some surgeons close the incision in 2 separate layers, with the first consisting of the tunica vaginalis and dartos muscle and the second consisting of the dermal edges. In this way, hematomas that can plague scrotal surgery have been avoided. If extensive dissection is necessary, placement of Penrose drains in the dependent portion of the scrotum can help prevent scrotal hematoma formation. Drains are generally removed within 24 hour after surgery.

Testicular atrophy remains the most dreaded complication. Atrophy results from injury to the internal spermatic artery as it traverses through the spermatic cord. In most cases, this is avoidable by careful dissection of the vas away from the adjacent cord. In addition, this injury can occur in patients receiving vasoepididymostomies if great care is not taken when the vas deferens is tunneled through the spermatic cord and placed in proximity to the epididymis.

The most common cause of operative failure is stenosis at the site of the vasovasostomy. The delayed closure rate of initially patent anastomoses is 3%-6% per year for vasovasostomies. An aggressive vasectomy resulting in a long segment of vas deferens removal may necessitate greater mobilization of vas deferens, in turn leading to a greater potential for devascularization, fibrosis, and stenosis.

Secondary azoospermia is another potential long-term complications. Kolettis et al. 7 reported a transient patency rate of 2.9%–5.3%, depending on the intraoperative presence of sperm. The formation of a sperm granuloma postoperatively can indicate leakage of sperm at the site of anastomosis and is a predictor of failure. Once sperm are identified in the ejaculate, cryopreservation should be considered in the event future failure occurs.

Vasovasostomy success rate

Chances of a successful vasovasostomy for vasectomy reversal decline over time. Vasovasostomy for vasectomy reversal is more successful during the first 10 years after vasectomy 8.

In general, vasovasostomy for vasectomy reversal 9:

- Leads to overall pregnancy rates of greater than 50%.

- Has the greatest chance of success within 3 years of the vasectomy.

- Leads to pregnancy only about 30% of the time if the reversal is done 10 years after vasectomy.

The following 3 factors portend the best surgical outcomes:

- The interval since the vasectomy was performed is one important factor. The Vasovasostomy Study Group, the largest multicenter group to assess vasovasostomy efficacy, found that an interval of less than 3 years resulted in patency rates of 97% and pregnancy rates of 76%. An interval exceeding 15 years resulted in patency and pregnancy rates of 71% and 30%, respectively 10. A study by Grober et al 11 analyzed the vasectomy reversal outcomes specifically among patients with vasal obstructive intervals of greater than 10 years. The study concluded that although the interval since vasectomy has a significant effect on the type of vasectomy reversal required, provided a surgeon is proficient in both microsurgical vasovasostomy and vasoepididymostomy, favorable semen parameters and patency and pregnancy rates can be achieved in men with a vasal obstructive intervals greater than 10 years.

- A second important factor is the microsurgical experience level of the surgeon. Performing the procedure without any magnification (ie, the macroscopic vasovasostomy) yields significantly inferior surgical results, with pregnancy rates ranging from 19%-55%. When the microsurgical technique is used, the success rates are markedly improved, regardless of whether the modified 1-layer or formal 2-layer anastomosis is used.

- Lastly, the presence of sperm and the quality of the fluid from the proximal vas is predictive of surgical success. Patency rates in men with sperm in the proximal vas fluid at the time of vasovasostomy exceed 90%, compared to pregnancy rates of 60% in men without sperm in the proximal vas. In the setting of no sperm in the vasal fluid, clear fluid predicts a higher success rate than thick opalescent fluid. A study by Scovell et al 12 concluded that the presence of whole sperm or sperm parts in the vasal fluid during vasectomy reversal is positively associated with postoperative patency.

- Herrel L, Hsiao W. Microsurgical vasovasostomy. Asian J Androl. 2013;15(1):44–48. doi:10.1038/aja.2012.79 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3739128[↩]

- Parekattil SJ, Gudeloglu A, Brahmbhatt J, Wharton J, Priola KB. Robotic assisted versus pure microsurgical vasectomy reversal: technique and prospective database controle trial. J Reconstr Microsurg. 2012. 28:435-44.[↩]

- Kavoussi PK. Validation of robot-assisted vasectomy reversal. Asian J Androl. 2015. 17:245-7.[↩]

- Abhishek P Patel, Ryan P Smith. Vasectomy Reversal: a clinical update. Asian Journal of Andrology. 1 March 2016. 18:365-371.[↩]

- Liang ZY, Zhang FB, Li LJ, et al. Clinical application of cross microsurgical vasovasostomy in scrotum for atypical obstructive azoospermia. J Zhejiang Univ Sci B. 2019;20(3):282–286. doi:10.1631/jzus.B1800303 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6421121[↩]

- Goldstein M. Surgical management of male infertility.In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, Partin AW, Peters CA, editors. Campbell–Walsh Urology. 10th ed Philadelphia, PA; Elsevier Saunders; 2012648–87.[↩]

- Kolettis PN, Fretz P, Burns JR, D’Amico AM, Box LC, et al. Secondary azoospermia after vasovasostomy. Urology. 2005;65:968–71.[↩]

- Roncari D, Jou MY (2011). Female and male sterilization. In RA Hatcher, et al., eds., Contraceptive Technology, 20th rev. ed., pp. 435–482. New York: Ardent Media.[↩]

- Speroff L, Darney PD (2011). Sterilization. In A Clinical Guide for Contraception, 5th ed., pp. 381–404. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins.[↩]

- Belker AM, Thomas AJ Jr, Fuchs EF, Konnak JW, Sharlip ID. Results of 1,469 microsurgical vasectomy reversals by the Vasovasostomy Study Group. J Urol. 1991 Mar. 145(3):505-11.[↩]

- Grober ED, Karpman E, Fanipour M. Vasectomy reversal outcomes among patients with vasal obstructive intervals greater than 10 years. Urology. 2014 Feb. 83 (2):320-3.[↩]

- Scovell JM, Mata DA, Ramasamy R, Herrel LA, Hsiao W, Lipshultz LI. Association between the presence of sperm in the vasal fluid during vasectomy reversal and postoperative patency: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Urology. 2015 Apr. 85 (4):809-13.[↩]