What is a Whipple procedure

Whipple procedure also called a pancreaticoduodenectomy, is a complex operation to remove a pancreatic tumor that occurs within the head of the pancreas and a lot of the tissue around it. Whipple procedure is named for Dr. Allen Whipple, the surgeon who designed and first performed this surgical technique in 1935, the Whipple procedure has continually improved over the years and can potentially enhance outcomes and quality of life for patients with pancreatic cancer.

While there are several variations in approach, a standard Whipple procedure involves the surgical removal of:

- The head and sometimes the neck of the pancreas

- The surrounding lymph nodes

- Portions of several nearby structures, such as the gall bladder, bile duct, duodenum, small intestine and stomach (antrum), if those organs are affected by cancer

During the Whipple procedure, surgeon makes a large cut is made in your belly, the surgeon will look at the pancreas and other organs in the area, including lymph nodes, to see if the pancreatic cancer has spread. Tissue samples will be taken for a biopsy. When the surgeon is satisfied that the tumor has not spread and can be removed entirely, he or she takes out the part of the pancreas containing the tumor. The surgeon will also take out the most of the duodenum (the first part of the small intestine), a portion of the bile duct, the gallbladder, and nearby lymph nodes. In some cases, the surgeon may remove the body of the pancreas, the entire duodenum and the lower part of the stomach is also removed.

The goal of surgery is to remove the tumor and some of the normal tissue around it. The normal tissue is examined under a microscope to see if it is free of cancer cells. This is known as getting “clear margins.” Having clear margins improves the chances—but doesn’t guarantee—that all cancer cells have been removed.

To complete a Whipple procedure, a surgeon will reattach the remaining pancreas and bile duct to the small intestine to restore the flow of food, bile and digestive enzymes through the digestive tract, to allow you to digest food normally after surgery. Because Whipple surgery is highly complex, it can take several hours to perform and requires significant surgical skill and experience. Additionally, surgeons often find variations among patients in the arrangement of blood vessels and ducts. For these reasons, finding a surgeon with the requisite skill level is essential.

Sometimes Whipple procedure can be done with laparoscopic surgery, using several small incisions instead of one large one.

On average, the surgery takes six hours to complete. Most patients stay in the hospital for one to two weeks following the Whipple procedure.

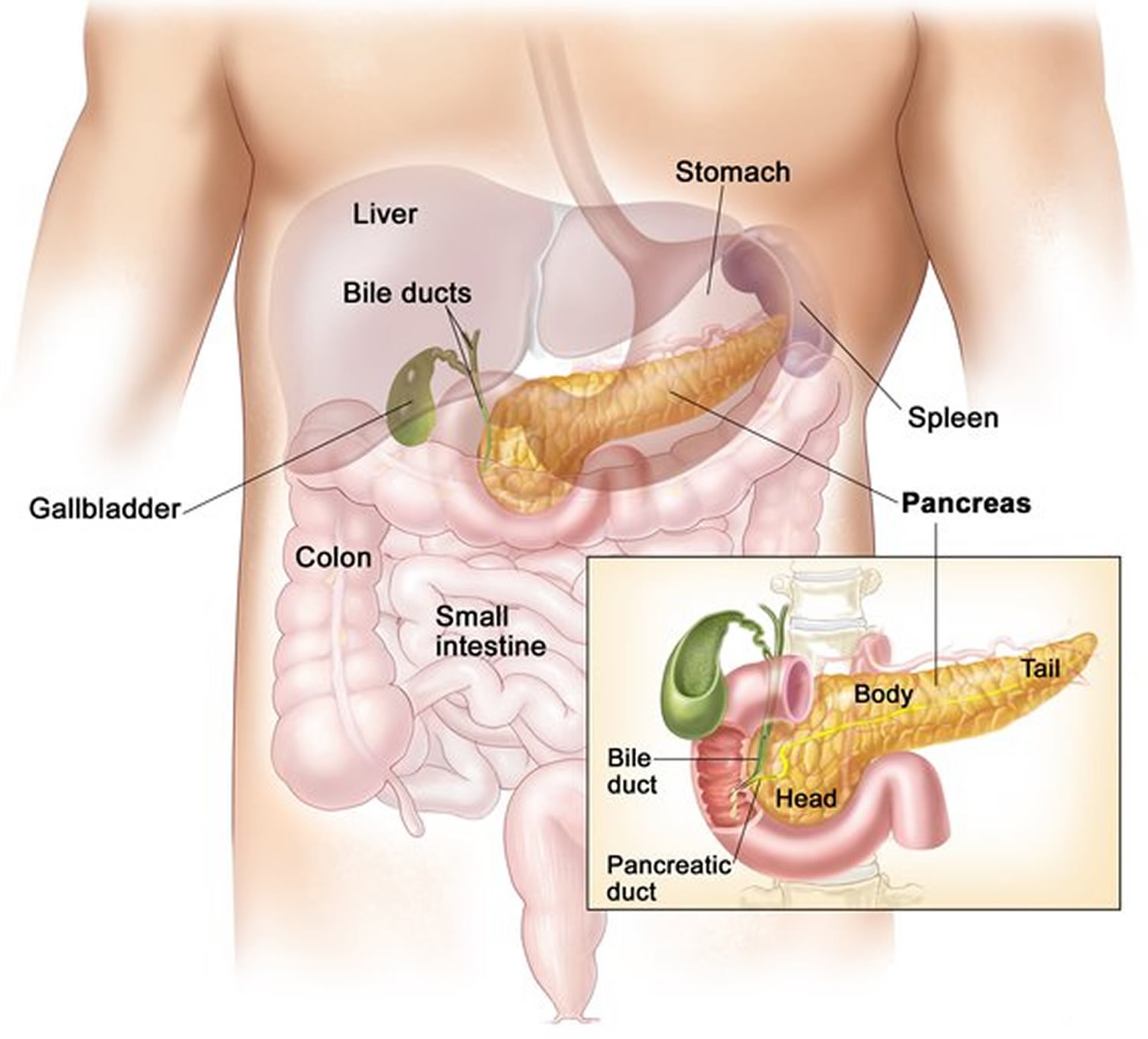

Figure 1. Pancreas

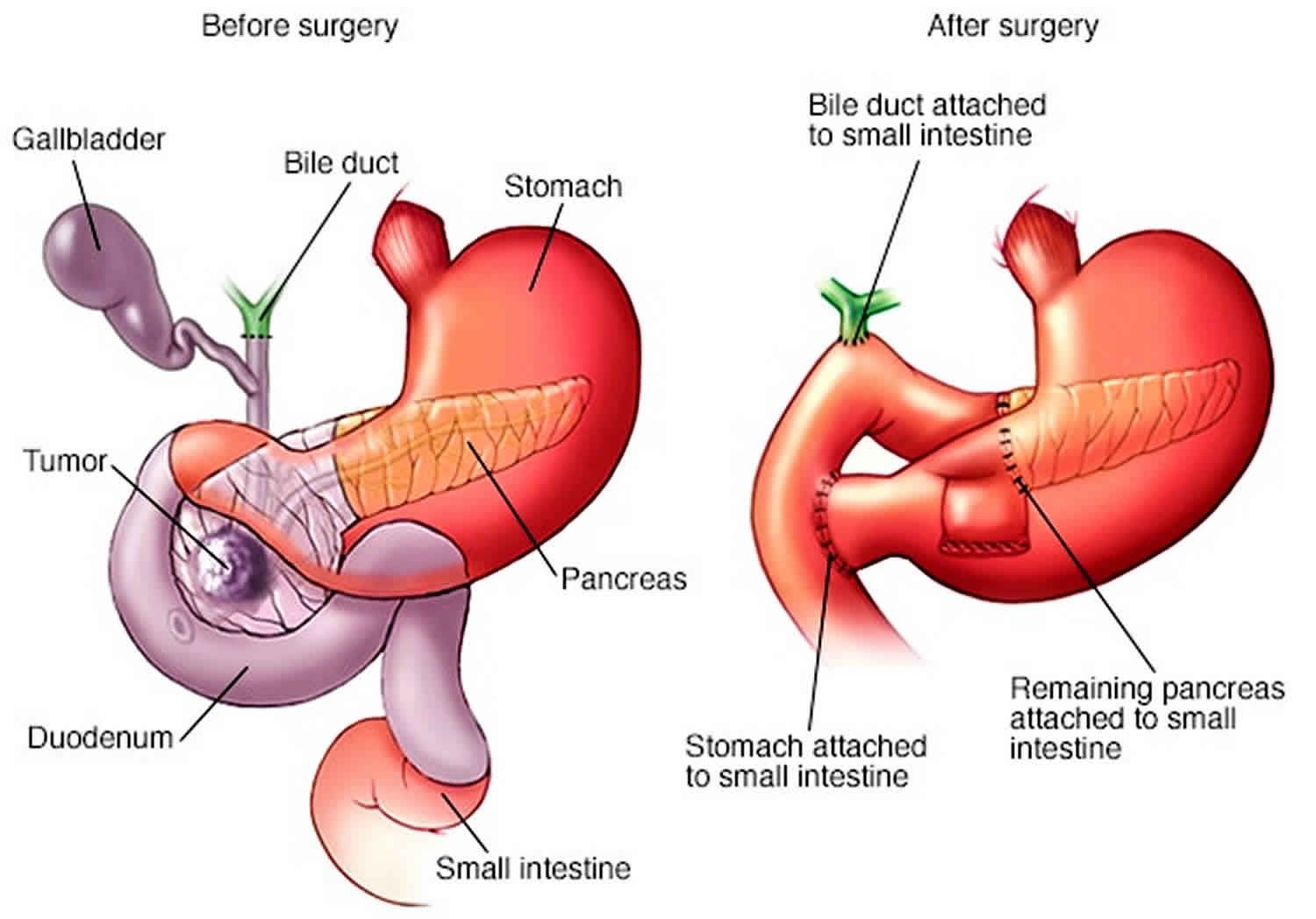

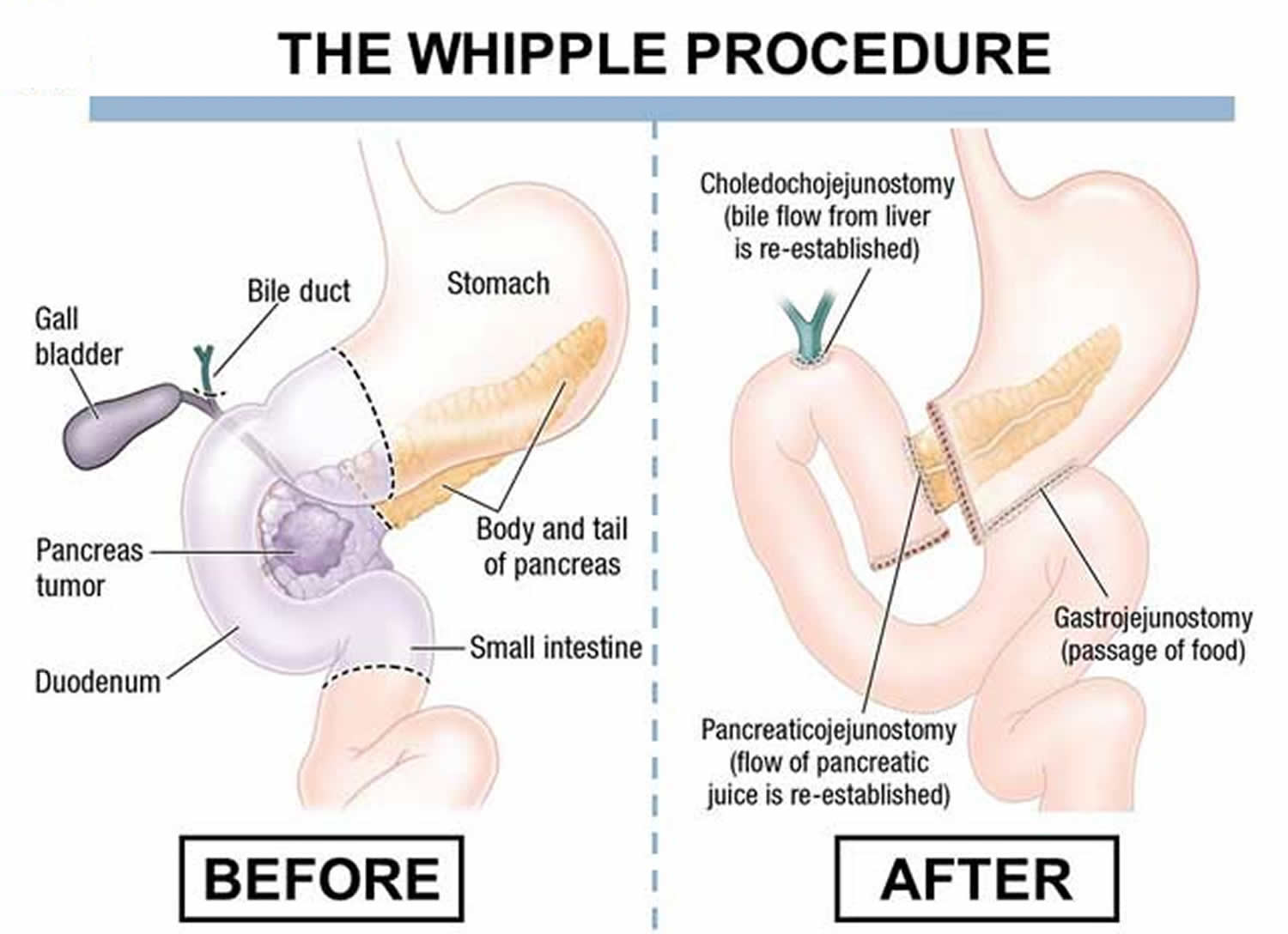

Figure 2. Whipple procedure

Why is Whipple procedure done?

A Whipple procedure may be a treatment option for people whose pancreas, duodenum or bile duct is affected by cancer or other disorder. The pancreas is a vital organ that lies in the upper abdomen, behind your stomach. It works closely with the liver and ducts that carry bile. The pancreas releases (secretes) enzymes that help you digest food, especially fats and protein. The pancreas also secretes hormones that help manage your blood sugar.

Your doctor may recommend you have a Whipple procedure to treat:

- Pancreatic cancer

- Pancreatic cysts

- Pancreatic tumors

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Ampullary cancer (the area where the bile duct and the and pancreatic duct enter the duodenum)

- Bile duct cancer (cholangiocarcinoma)

- Neuroendocrine tumors

- Small bowel cancer

- Cancer of the duodenum (first part of the small intestine)

- Trauma to the pancreas or small intestine

- Other tumors or disorders involving the pancreas, duodenum or bile ducts

The goal of doing a Whipple procedure for cancer is to remove the tumor and prevent it from growing and spreading to other organs. This is the only treatment that can lead to prolonged survival and cure for most of these tumors.

Who is eligible for Whipple procedure?

If a tumor is in the head of the pancreas, has not spread to other areas of the body and can be removed (resected) surgically, the Whipple procedure may be attempted. Approximately 15 to 20 percent of patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma (the most common type of pancreatic cancer) have surgically resectable tumors.

About 30 to 50 percent of patients who are eligible for surgery are told they are ineligible. The Pancreatic Cancer Action Network strongly recommends you see a surgeon who performs a high volume of pancreatic surgeries (more than 15 per year) to determine eligibility.

Determining a patient’s eligibility for surgery is not always easy. Even sophisticated imaging tests may not provide perfect information. In some cases, despite testing before surgery, the surgeon may find during the procedure that the cancer has spread or cannot be removed. Therefore, the planned operation cannot be completed.

Is the Whipple procedure worth it?

The type of operation performed for removal of pancreatic cancer is based on the location of the tumor. For tumors of the head and neck of the pancreas a Whipple procedure also called a pancreaticoduodenectomy, is performed. The Whipple procedure is a difficult and demanding operation and can have serious risks. However, this surgery is often lifesaving, particularly for people with pancreatic cancer. For most tumors and cancers of the pancreas, the Whipple procedure is the only known cure.

Because Whipple surgery is both difficult and demanding, it is best performed by a surgeon who has highly refined skills. In fact; recent research studies confirm that Whipple surgery outcomes are largely dependent on the experience level of the treating surgeon. Because a surgeon’s skills are further honed with each Whipple procedure performed, the American Cancer Society has recommended that patients seek treatment at high-volume cancer centers, where surgeons complete these complex procedures on a regular basis.

Related procedures

Depending on your situation, your doctor may talk with you about other pancreatic operations. Seek a second opinion from a specialized surgeon if needed. Options include:

- Surgery for tumors or disorders in the body and tail of the pancreas. Surgery to remove the left side (body and tail) of the pancreas is called a distal pancreatectomy. With this procedure, your surgeon may also need to remove your spleen.

- Surgery to remove the entire pancreas. This is called total pancreatectomy. You can live relatively normally without a pancreas but will need lifelong insulin and enzyme replacement.

- Surgery for tumors affecting nearby blood vessels. Many people are not considered eligible for the Whipple procedure or other pancreatic surgeries if their tumors involve nearby blood vessels. At a very few medical centers in the United States, highly specialized and experienced surgeons will safely perform these operations in select patients. The procedures involve also removing and reconstructing parts of blood vessels.

Who are top surgeons for Whipple procedure?

Pancreatic surgery is very complicated. Data show high volume surgeons at high volume hospitals have higher success rates and fewer complications. The Pancreatic Cancer Action Network strongly recommends you have a high volume pancreatic surgeon (more than 15 surgeries per year) perform the surgery.

Pancreatic Cancer Action Network Patient Central (https://www.pancan.org/facing-pancreatic-cancer/patient-services/) can provide more information, including a list of institutions and doctors who perform a high volume of pancreatic surgeries.

Whipple procedure complications

The Whipple procedure is a technically difficult operation, often involving open surgery. It carries risks both during and after surgery. These may include:

- Bleeding at the surgical areas

- Infection of the incision area or inside your abdomen

- Delayed emptying of the stomach, which may make it difficult to eat or to keep food down temporarily

- Leakage from the pancreas or bile duct connection

- Diabetes, temporary or permanent

Extensive research shows that surgeries result in fewer complications when done by highly experienced surgeons at centers that do many of these operations. Don’t hesitate to ask about your surgeon’s and hospital’s experience with Whipple procedures and other pancreatic operations. If you have any doubts, get a second opinion.

The presence of delayed gastric emptying may necessitate prolonged nasogastric decompression or total parenteral nutrition (TPN) with enteral feeding access failure 1. Use jejunal feedings for as long as necessary, and beware of aspiration.

Pancreatic leak with consequence may occur and may include pancreatic fluid collection, pancreatic fistula formation 2, intra-abdominal abscess, or sepsis.

gastroduodenal artery complications that may develop include pseudoaneurysm, gastroduodenal artery-enteric fistula, and gastroduodenal artery stump blowout with massive hemorrhage (eg, bleeding from abdominal drains, massive gastrointestinal [GI] bleeding). gastroduodenal artery stump blowout with massive hemorrhage is initiated by inflammation from pancreatic leak and rarely occurs before postoperative day 10. This condition is treated with selective angiography with stenting or embolization of the hepatic artery. Reoperation is performed only as a last resort.

Other perioperative problems include the following:

- Feeding jejunal tube management failures (luminal rotation, dislodgment, obstruction)

- Prolonged ileus

- Small-bowel obstruction

- Internal herniation of bowel

- Small-bowel volvulus

- Critical illness such as sepsis, respiratory failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, renal failure, and multisystem organ failure

- Death (< 4%)

Long-term morbidity

The following are included in the possible long-term morbidity of Whipple procedure:

- Recurrence of malignancy, such as local recurrence at the retroperitoneal margin or distal recurrence in the liver, peritoneum, or lungs

- Pancreatic insufficiency – Exocrine (~40%), endocrine (~20%)

- Pancreatic anastomotic stricture (recurrent pancreatitis, chronic pancreatic pain)

- Anastomotic failure (any)

- Anastomotic stricture (any)

- Small-bowel obstruction

- Internal herniation of bowel

- Small-bowel volvulus

Whipple procedure steps

Whipple procedure preparation

Your surgeon will review several factors to evaluate which approach to your surgery is best in your situation. He or she will also assess your condition and ensure that you are healthy enough for a complex operation. You may require some additional medical tests and optimization of some of your health conditions before proceeding to surgery.

The following laboratory and imaging studies should be obtained to help determine the patient’s fitness for surgery:

- Complete blood count (CBC), basic metabolic panel (BMP), liver function tests (LFTs), and a coagulation panel

- Tumor markers, such as CA 19-9 and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA)

- Abdominal ultrasonography – Primary imaging modality for evaluation of biliary obstruction and/or ascites

- High-quality computed tomography (CT) – Thin cuts are needed to assess criteria for tumor resectability

- Chest x-ray (CXR) or chest CT – Metastatic workup

Endoscopic ultrasonography (EUS), fine-needle aspiration (FNA), or both are occasionally performed in a patient who is being considered for PPPD. EUS, though not routinely employed, is helpful when pancreatic head masses are poorly detected on CT. Tumor aspiration is not routinely employed for preoperative tissue diagnosis, because FNA results do not affect surgical decision making; however, confirmation of malignancy can be useful in the setting of neoadjuvant therapy. Also, there is a finite risk of seeding the peritoneum with malignant disease from needle biopsy.

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) may be performed for preoperative endobiliary stent placement in the setting of cholangitis or biliary obstruction with anticipated delay to surgery.

Patients will be restaged after neoadjuvant therapy before the surgical procedure.

A Whipple procedure may be done in various ways:

- Open surgery. During an open procedure, your surgeon makes an incision in your abdomen in order to access your pancreas. This is the most common approach and the most studied.

- Laparoscopic surgery. During laparoscopic surgery, the surgeon makes several smaller incisions in your abdomen and inserts special instruments, including a camera that transmits video to a monitor in the operating room. The surgeon watches the monitor to guide the surgical tools in performing the Whipple procedure. Laparoscopic surgery is a type of minimally invasive surgery.

- Robotic surgery. Robotic surgery is a type of minimally invasive surgery in which the surgical tools are attached to a mechanical device (robot). The surgeon sits at a console nearby and uses hand controls to direct the robot. A surgical robot can use tools in tight spaces and around corners, where human hands may be too large to be effective.

Minimally invasive surgery offers some benefits, such as lower blood loss and a quicker recovery in those without complications. But it also takes longer, which can be hard on the body. Sometimes a procedure may begin with minimally invasive surgery, but complications or technical difficulty require the surgeon to make an open incision to finish the operation.

Before your Whipple operation, your surgeon will explain to you what to expect before, during and after surgery, including potential risks. Your treatment team will talk with you and your family about how your surgery will affect your quality of life. Sometimes the Whipple procedure or other pancreas operations being performed for cancer is preceded or followed by chemotherapy, radiation therapy or both. Talk with your doctor about concerns you may have about your surgery and various other treatment options either before or after your operation.

Before being admitted to the hospital, talk to your family or friends about your hospital stay and discuss any help you may need from them when you return home. You will need someone’s help for the first couple of weeks after discharge from the hospital. Your doctor and treatment team may give you instructions to follow during your recovery when you return home.

Food and medications

Talk to your doctor about:

- When you can take your regular medications and whether you can take them either the night before or the morning of surgery

- When you need to stop eating or drinking the night before the surgery

- Allergies or reactions you have had to medications

- Any history of difficulty or severe nausea with anesthesia

Before the procedure

The morning of surgery, you’ll check into the admission desk and register. Nurses and staff members will confirm your name, date of birth, procedure and surgeon. You will then need to change into a surgical gown in preparation for surgery.

Before your surgery, an intravenous (IV) line is put into a vein, usually in your arm. This is used to inject fluid and medication into your veins as needed. You may also receive some medication to help you relax if you are nervous.

You may also undergo placement of an epidural catheter or a spinal injection in addition to local nerve blocks to the abdominal wall. These procedures allow you to recover with minimal pain and discomfort after surgery and help to decrease the amount of narcotic pain medication you will need.

Whipple procedure

A surgical team works together to enable you to have a safe and effective surgery. The team is made up of pancreatic surgeons, specialized surgical nurses, anesthesiologists and anesthetists — doctors and nurses trained in giving medication that causes you to sleep during surgery — and others.

After you are asleep, additional intravenous lines may be placed with other monitoring devices, depending on the complexity of the operation and your overall health conditions. Another tube, called a urinary catheter, will be inserted into your bladder. This drains urine during and after surgery. It is typically removed one or two days after surgery.

Surgery may take four to 12 hours, depending on which approach is used and the complexity of the operation. Whipple surgery is done using general anesthesia, so you’ll be asleep and unaware during the operation.

The surgeon makes an incision in your abdomen to access your internal organs. The location and size of your incision varies according to your surgeon’s approach and your particular situation. For a Whipple procedure, the head of the pancreas, the beginning of the small intestine (duodenum), the gallbladder and the bile duct are removed.

In certain situations, the Whipple procedure may also involve removing a portion of the stomach or the nearby lymph nodes. Other types of pancreatic operations also may be performed, depending on your situation.

Your surgeon then reconnects the remaining parts of your pancreas, stomach and intestines to allow you to digest food normally.

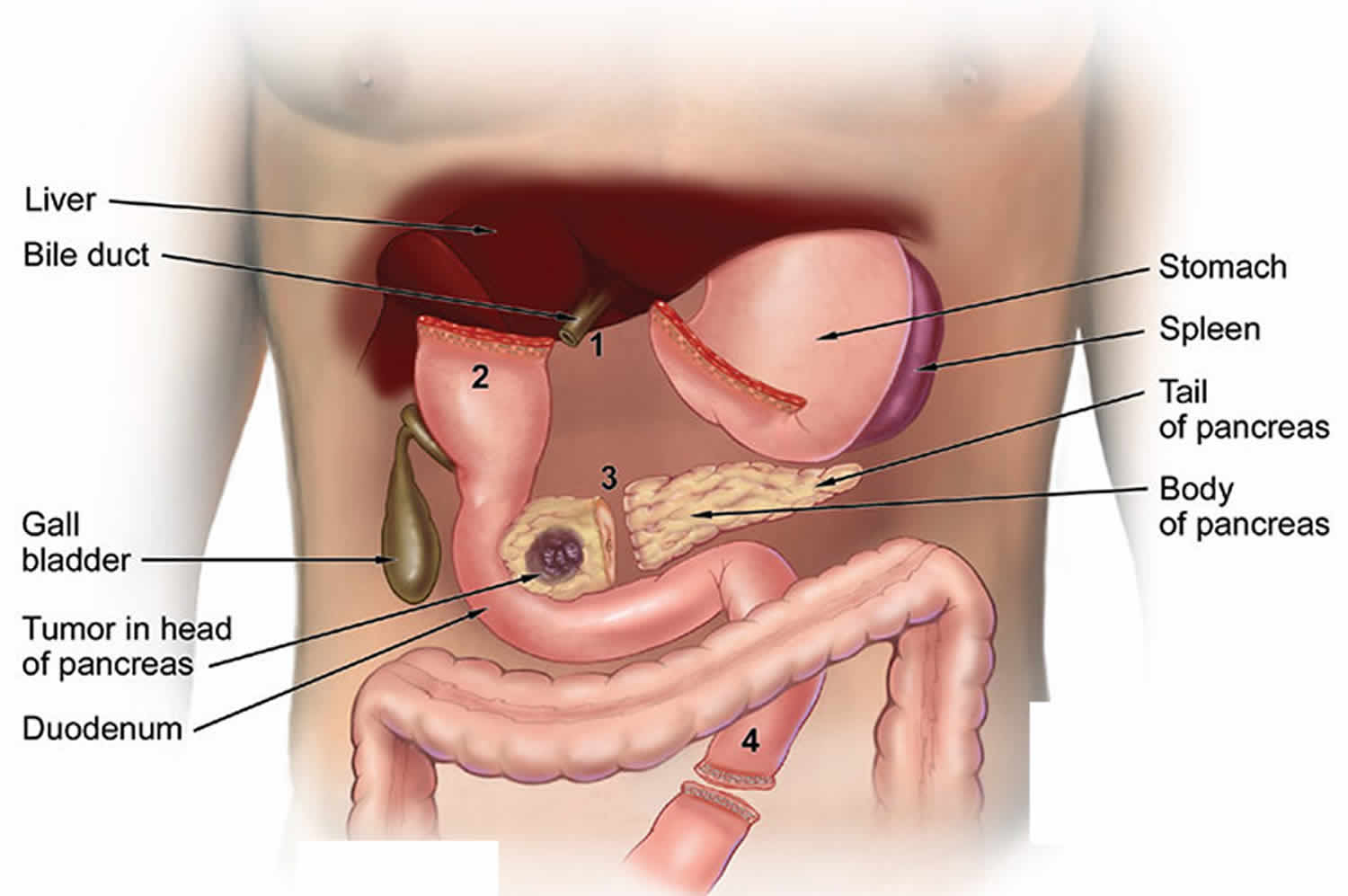

Figure 3. Whipple procedure step 1

Footnote: Figure 3 shows shows the surgical separation of the (1) bile duct, (2) stomach, (3) head of the pancreas and (4) small intestine.

Footnote: Figure 3 shows shows the surgical separation of the (1) bile duct, (2) stomach, (3) head of the pancreas and (4) small intestine.Figure 4. Whipple procedure step 2

Footnote: Figure 4 shows the re-attachment of the (5) bile duct to the small intestine, (6) remaining pancreas to the small intestine and (7) stomach to the small intestine.

Whipple procedure technique

The steps for completion of a Whipple procedure or pylorus-preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy, can be thought of as a clockwise journey. The surgeon begins at the ascending colon and hepatic flexure to obtain exposure of the superior mesenteric vein, then moves to the porta hepatis for cholecystectomy and portal lymph node dissection, followed by transection of the stomach or proximal duodenum. He or she then proceeds to jejunal transection and, finally, pancreatic transection, with completion of retroperitoneal dissection and removal of the specimen en bloc.

The reconstructions can be performed in a counterclockwise direction: The surgeon starts with creation of jejunal feeding access and then proceeds to creation of the pancreaticojejunal, choledochojejunal, and enterojejunal anastomoses. Venous reconstructions are also undertaken in select patients.

Laparotomy and abdominal exploration

Laparotomy is performed with a generous midline incision or bilateral subcostal incisions. The liver is palpated, the peritoneum is inspected, and the paraortic lymph nodes and the root of the mesentery are evaluated.

Intraoperative hepatic ultrasonography may be used when preoperative imaging is not definitive. In addition, abdominal exploration may be undertaken as staging laparoscopy before laparotomy in patients with advanced disease who are suspected of being at risk for radiographically silent metastatic disease.

Exposure of superior mesenteric artery and extended kocherization

A self-retaining retractor facilitates general exposure of the operative field. The falciform ligament is identified and preserved for later use (to protect the gastroduodenal artery [GDA] stump). The ascending colon and hepatic flexure are mobilized by using a Cattell-Brasch maneuver or right medial visceral rotation to expose the third and fourth portions of the duodenum.

The lesser sac is then opened and entered. Here, the middle colic vein is encountered and ligated, facilitating exposure of the superior mesenteric vein. The gastroepiploic vein is often seen entering common trunk with the middle colic vein and can be ligated when encountered.

Next, an extended Kocher maneuver is performed from the right ureter and right gonadal vein junction (which is ligated and mobilized) until the aorta and the crossing left renal vein are identified. Intervening lymphatic tissues should be mobilized as well. Here, the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) should be identifiable.

Cholecystectomy and portal dissection

The celiac axis is located, and the right gastric artery is identified and preserved. The node of the common hepatic artery is removed, and the common hepatic artery is dissected proximal and distal to the gastroduodenal artery takeoff. This is done carefully (because the common hepatic artery is fragile), and the gastroduodenal artery is transected. Cholecystectomy is performed with transection of the specimen at the common hepatic duct just before the cystic duct takeoff. The common hepatic duct margin undergoes intraoperative pathologic analysis and is extended as necessary.

Given the anatomic variability of hepatic arterial circulation, the surgeon must look for a replaced right hepatic artery or replaced common hepatic artery. After the origins of the aforementioned are identified, medial retraction applied to the common hepatic artery exposes the anterior surface of the portal vein (PV). The portal vein is followed to its junction with the pancreatic neck, with the surgeon taking great care to avoid traction injury to the posterior pancreatic duodenal vein.

Duodenal transection if Whipple procedure permissible

In concordance with accepted oncologic principles, bulky neoplasms of the pancreatic head, tumors progressing to the first or second part of the duodenum, or clinically positive regional lymph nodes noted at this juncture preclude pylorus preservation. If Whipple procedure is implementable, then the duodenum is transected 2-3 cm distal to the pylorus. This duodenal cuff must be made long enough to withstand later revision during creation of the duodenojejunal anastomosis.

The gastroepiploic artery and vein are divided, and the right gastric artery is once again identified and protected. The duodenum is divided 2-3 cm distal to the pylorus. The jejunum is transected at least 10 cm distal to the ligament of Treitz. The mesenteries of both transected small-bowel stumps are divided as well, and the duodenum and jejunum are reflected below the mesenteric vessels.

Division of pancreas

The pancreas is transected about 2 cm distal to the pylorus at the level of the portal vein, thus exposing the underlying superior mesenteric vein-portal vein confluence. If the tumor is adherent to the portal vein, superior mesenteric vein, or superior mesenteric vein-portal vein confluence, the pancreatic division plane may have to be revised more distally in order to accommodate vein reconstruction. The tumor is carefully separated from the named venous structures. If the first jejunal branch of the superior mesenteric vein is lacerated here, the venous injury is difficult to control, and attempted repair of such an injury can damage the superior mesenteric artery.

The tumor is reflected rightward and separated from the right lateral border of the superior mesenteric artery; it is important to completely resect the uncinate process in order to achieve an R0 resection (ie, surgical margins negative for tumor). The superior mesenteric artery is then exposed by the retracted superior mesenteric vein-portal vein confluence, and it is dissected carefully to visualize the inferior pancreaticoduodenal artery. This must be ligated securely; failure to do so can cause retroperitoneal hemorrhage.

Removal and orientation of specimen

The specimen is removed en bloc and oriented for pathology. The retroperitoneal margin is inked for pathologic frozen section analysis. A grossly positive retroperitoneal margin represents a technical failure to achieve the intended R0 resection goal. A microscopically positive retroperitoneal margin can occur with 10-20% of pancreaticoduodenal resections.

Vascular reconstruction

Vascular reconstruction after Whipple procedure is extensive and beyond the scope of this discussion. The reader is directed to the resources in the References section.

Pancreatic reconstruction

The pancreatic remnant is first mobilized along its length for a few centimeters. Then, the transected jejunum is brought through a defect in the transverse mesocolon adjacent to the middle colic vessels. A pancreaticojejunal anastomosis is created with the understanding that pancreatic fistula formation depends on the technical integrity of the anastomosis, as well as the quality of the pancreatic tissue.

A two-layer end-to-side pancreaticojejunostomy, also known as a duct-to-mucosa reconstruction, is performed. This indicates full-thickness pancreatic duct–to–jejunal wall closure.

First, the posterior outer row of interrupted seromuscular sutures is placed between the jejunal side wall and the pancreatic parenchyma. The jejunum is opened longitudinally anterior to this. The inner circumferential layer of interrupted, full-thickness sutures reapproximate the cut end of the pancreatic duct with jejunal wall. The posterior sutures are tied inside the anastomosis, a pancreatic stent is placed, and the remaining sutures are tied on the outside. The anterior outer layer of sutures is placed as a row of interrupted seromuscular sutures.

Alternatively, invagination of the distal pancreatic stump into the jejunum can be performed in an end-to-end or end-to-side manner. The inner layer of sutures is placed as described above, and the outer layer of sutures is placed to invaginate the pancreatic remnant. This is useful when the pancreatic duct is not dilated and when the parenchyma is too soft to hold against jejunal seromuscular sutures.

Biliary reconstruction

Hepaticojejunostomy is performed as a one-layer end-to-side anastomosis between the common hepatic duct remnant and a site on the jejunum distal to the pancreaticojejunal anastomosis. It is critical to align the bile duct and jejunum without tension before suture placement.

Enteric reconstruction

The jejunum is traced distal to the biliary reconstruction and brought to lie antecolically. The cuff of duodenum is revised, preserving at least 1.5 cm of postpyloric duodenum to preserve the blood supply to the anastomosis. An antecolic end-to-side anastomosis between the duodenum and jejunum is created with a single layer of continuous suture. Some have found antecolic gastrointestinal resconstruction to be associated with a lower incidence of delayed gastric emptying than retrocolic reconstruction 3; however, others have not 4.

Closing maneuvers

A feeding jejunostomy is created distal to the duodenojejunal anastomosis by using a Witzel technique to maintain postoperative enteral feeding access. Then, the falciform ligament is located and used to cover the gastroduodenal artery stump so as to prevent gastroduodenal artery pseudoaneurysm formation in the event of pancreatic leak (see Complications). As a rule, closed-suction transcutaneous drains are placed at the pancreatic anastomosis and biliary anastomosis, with additional drains per surgeon preference. The abdomen is closed in the standard fashion.

A study by Gupta et al 5 suggested that negative-pressure wound therapy may help lower the incidence of surgical-site infection after Whipple procedure.

Whipple procedure recovery

After your Whipple procedure, you can expect to:

- Stay in the general surgical unit. Most people will go directly to a general surgical nursing floor after surgery to recover. Nursing staff and the entire surgical team will be monitoring your progress several times a day and watching for any signs of infection or complications. Your diet will be slowly advanced as tolerated. Most people will be walking immediately after the operation. Expect to spend at least a week in the hospital, depending on your overall recovery.

- Stay in the intensive care unit (ICU) for a few days. If you have certain medical conditions or a complex case, you may be admitted to the ICU after surgery. ICU doctors and nurses will monitor your condition continuously to watch for signs of complications. They’ll give you fluids, nutrition and medications through intravenous (IV) lines. Other tubes will drain urine from your bladder and drain fluid and blood from the surgical area.

Patients undergoing a Whipple procedure will be in the hospital for one to two weeks following surgery to be monitored for any signs of complications. For the first few days following surgery, patients will be restricted from solid food. Specific instructions will be provided to patients for their recovery at home. Patients may feel fatigued for around two months following surgery.

After discharge from the hospital, most people can return directly home to continue recovery. Some people are asked to stay nearby for several days for monitoring and follow-up visits. Older adults and people with significant health concerns may require a temporary stay in a skilled rehabilitation facility. Talk to your surgeon and team if you are concerned about your home recovery.

Most people are able to return to their usual activities four to six weeks after surgery. How long it takes you to recover may depend on your physical condition before your surgery and the complexity of your operation.

Whipple procedure diet

The Whipple procedure may cause challenges, including digestive difficulties, for a long time.

- It can take a patient anywhere from a few months to a year to feel relatively “normal” again.

- It takes time for the digestive system to start working again, and some patients must make permanent diet changes to reduce symptoms such as diarrhea, gas and stomach pain.

- Many patients also take pancreatic enzymes to help digest food properly.

Whipple procedure survival rate

Your chances of long-term survival after a Whipple procedure depend on your particular situation. For most tumors and cancers of the pancreas, the Whipple procedure is the only known cure.

Talk to your treatment team, family and friends if you feel stressed, worried or depressed. It may help to discuss how you’re feeling. You may want to consider joining a support group of people who have experienced a Whipple procedure or talking with a professional counselor.

Long-term prognosis for pancreatic cancer depends on the size and type of the tumor, lymph node involvement and degree of metastasis (spread) at the time of diagnosis. The earlier pancreatic cancer is diagnosed and treated, the better the prognosis.

Unfortunately, pancreatic cancer usually shows little or no symptoms until it has advanced and spread. Therefore, most cases (up to 80 percent) are diagnosed at later, more difficult-to-treat stages.

Survival rates tell you what portion of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time (usually 5 years) after they were diagnosed. They can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding about how likely it is that your treatment will be successful. Some people will want to know the survival rates for their cancer, and some people won’t. If you don’t want to know, you don’t have to.

Pancreatic cancer survival rate

Statistics on the outlook for a certain type and stage of cancer are often given as 5-year survival rates, but many people live longer – often much longer – than 5 years. The 5-year survival rate is the percentage of people who live at least 5 years after being diagnosed with cancer. For example, a 5-year survival rate of 70% means that an estimated 70 out of 100 people who have that cancer are still alive 5 years after being diagnosed. Keep in mind, however, that many of these people live much longer than 5 years after diagnosis. In general, people who can be treated with surgery tend to live longer than those not treated with surgery.

But remember, the 5-year relative survival rates are estimates – your outlook can vary based on a number of factors specific to you.

Cancer survival rates don’t tell the whole story

Survival rates are often based on previous outcomes of large numbers of people who had the disease, but they can’t predict what will happen in any particular person’s case. There are a number of limitations to remember:

- The numbers below are among the most current available. But to get 5-year survival rates, doctors have to look at people who were treated at least 5 years ago. As treatments are improving over time, people who are now being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer may have a better outlook than these statistics show.

- These statistics are based on the stage of the cancer when it was first diagnosed. They do not apply to cancers that later come back or spread, for example.

- The outlook for people with pancreatic cancer varies by the stage (extent) of the cancer – in general, the survival rates are higher for people with earlier stage cancers. But many other factors can affect a person’s outlook, such as age and overall health, and how well the cancer responds to treatment. The outlook for each person is specific to their circumstances.

- Survival rates tell you what portion of people with the same type and stage of cancer are still alive a certain amount of time (usually 5 years) after they were diagnosed. These numbers can’t tell you how long you will live, but they may help give you a better understanding about how likely it is that your treatment will be successful. Some people will want to know the survival rates for their cancer, and some people won’t.

Your doctor can tell you how these numbers may apply to you, as he or she is familiar with your particular situation.

Table 1. 5-year relative survival rates for pancreatic cancer (based on people diagnosed with pancreatic cancer between 2008 and 2014)

| SEER Stage | 5-year Relative Survival Rate |

| Localized | 34% |

| Regional | 12% |

| Distant | 3% |

| All SEER stages combined | 9% |

Footnote: SEER= Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results

Understanding the numbers

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread, but your age, overall health, how well the cancer responds to treatment, tumor grade, extent of resection, level of tumor marker (CA 19-9) and other factors will also affect your outlook.

- People now being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least five years earlier.

- Localized means that the cancer is only growing in the pancreas.This usually includes Stage 0 and I cancers).

- Regional means that the cancer has spread to nearby lymph nodes or tissues. This typically includes Stage II and III cancers.

- Distant means that the cancer has spread to organs or lymph nodes away from the tumor, and includes all stage IV cancers.

Survival rates for exocrine pancreatic cancer

The numbers below come from the National Cancer Data Base and are based on people diagnosed with exocrine pancreatic cancer between 1992 and 1998 6. In general, people who can be treated with surgery tend to live longer than those not treated with surgery.

- The 5-year survival rate for people with stage IA pancreatic cancer is about 14%. For stage IB cancer, the 5-year survival rate is about 12%.

- For stage IIA pancreatic cancer, the 5-year survival rate is about 7%. For stage IIB cancer, the 5-year survival rate is about 5%.

- The 5-year survival rate for stage III pancreatic cancer is about 3%.

- Stage IV pancreatic cancer has a 5-year survival rate of about 1%. Still, there are often treatment options available for people with this stage of cancer.

According to Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program (SEER 18) 2007-2013, All Races, Both Sexes ~ 8.2 Percent Surviving 5 Years 7.

Survival by Stage

Cancer stage at diagnosis, which refers to extent of a cancer in the body, determines treatment options and has a strong influence on the length of survival 7. In general, if the cancer is found only in the part of the body where it started it is localized (sometimes referred to as stage 1). If it has spread to a different part of the body, the stage is regional or distant. The earlier pancreatic cancer is caught, the better chance a person has of surviving five years after being diagnosed. For pancreatic cancer, 9.7% are diagnosed at the local stage. The 5-year survival for localized pancreatic cancer is 31.5%.

Remember, these survival rates are only estimates – they can’t predict what will happen to any individual person. We understand that these statistics can be confusing and may lead you to have more questions. Talk to your doctor to better understand your specific situation.

Survival rates for neuroendocrine pancreatic tumors (treated with surgery)

For pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (NETs), survival statistics by stage are only available for patients treated with surgery. These numbers come from the National Cancer Data Base and are based on patients diagnosed between 1985 and 2004.

- The 5-year survival rate for people with stage I pancreatic NETs is about 61%.

- For stage II pancreatic NETs, the 5-year survival rate is about 52%.

- The 5-year relative survival rate for stage III pancreatic NETs is about 41%.

- Stage IV pancreatic NETs have a 5-year survival rate of about 16%. Still, there are often treatment options available for people with these cancers.

In this database, the overall 5-year survival rate for people who did not have their tumors removed by surgery was 16%.

- Mohammed S, Van Buren Ii G, McElhany A, Silberfein EJ, Fisher WE. Delayed gastric emptying following pancreaticoduodenectomy: Incidence, risk factors, and healthcare utilization. World J Gastrointest Surg. 2017 Mar 27. 9 (3):73-81[↩]

- Liang X, Shi LG, Hao J, Liu AA, Chen DL, Hu XG, et al. Risk factors and managements of hemorrhage associated with pancreatic fistula after pancreaticoduodenectomy. Hepatobiliary Pancreat Dis Int. 2017 Oct 15. 16 (5):537-544.[↩]

- Hanna MM, Tamariz L, Gadde R, Allen C, Sleeman D, Livingstone A, et al. Delayed gastric emptying after pylorus preserving pancreaticoduodenectomy–does gastrointestinal reconstruction technique matter?. Am J Surg. 2016 Apr. 211 (4):810-9.[↩]

- Qian D, Lu Z, Jackson R, Wu J, Liu X, Cai B, et al. Effect of antecolic or retrocolic route of gastroenteric anastomosis on delayed gastric emptying after pancreaticoduodenectomy: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pancreatology. 2016 Jan-Feb. 16 (1):142-50. [↩]

- Gupta R, Darby GC, Imagawa DK. Efficacy of Negative Pressure Wound Treatment in Preventing Surgical Site Infections after Whipple Procedures. Am Surg. 2017 Oct 1. 83 (10):1166-1169[↩]

- Pancreatic Cancer Survival Rates, by Stage. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/pancreatic-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html[↩]

- Cancer Stat Facts: Pancreatic Cancer. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/pancreas.html[↩][↩]