Yaws

Yaws is a non-venereal endemic treponemal infection caused by Treponema pallidum sub-species pertenue, a spirochaete bacterium closely related to Treponema pallidum sub-species pallidum, the agent of venereal syphilis 1. Yaws does not occur in the United States. Yaws is a long-term (chronic) tropical bacterial skin infection that may also infect bones and joints in its late stages, that predominantly affects children living in certain tropical regions 2. Yaws may be locally known as pian, parangi, paru, patek, buoba, coko and tona. Yaws spreads by skin-to-skin contact and like syphilis, occurs in distinct clinical stages. Yaws causes lesions of the skin, mucous membranes and bones which, without treatment, can become chronic and destructive. Treponema pallidum sub-species pertenue, like its sexually-transmitted counterpart Treponema pallidum, is exquisitely sensitive to penicillin. Infection with yaws or syphilis results in reactive treponemal serology and there is no widely available test to distinguish between these infections 2. Thus, migration of people from yaws-endemic areas to developed countries may present clinicians with diagnostic dilemmas.

There is some evidence that the manifestations of yaws in the modern era are less florid than previously reported. It has been postulated that use of penicillins to treat other conditions may be responsible for this. The differential diagnosis of yaws lesions is wide and includes syphilis, leishmaniasis, leprosy and Buruli ulcer, as well as non-infectious causes. Discussion with a physician with expertise in tropical medicine is recommended as the differential diagnosis and choice of investigations will vary depending on the patient’s country of origin.

Yaws was nearly eradicated by a worldwide treatment program in the 1950-60s 1. Between 1959-1961, people from Fiji, Samoa, Tonga, Cook Islands and Tokelau Islands were given injections of penicillin as part of a World Health Organisation (WHO) campaign 1. According to the last estimate by the World Health Organization (WHO), in 1995, the prevalence of endemic treponematoses, mostly yaws, was 2.5 million, with 460,000 cases being infectious 3. In 2006, India declared that yaws had been eliminated in that country. However, a 2007 WHO report suggests yaws is on the rise again, mostly in poor, rural areas of West and Central Africa, Southeast Asia (Indonesia), and some Pacific Islands, such as Papua New Guinea and the Solomon Islands 4. According to the WHO, in 2010, yaws continues to be common in areas with the poorest population; the endemic nations included Indonesia, Timor-Leste, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Benin, Cameroon, Central Africa Republic, Congo, Cote d’Ivoire, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Sierra Leone, and Togo 5.

The population at risk of contracting yaws worldwide is estimated to be 34 million, evenly distributed between men and women (17 million each). Yaws primarily affects children living in poor, densely-populated rural areas. The concentration of yaws in warm, humid climates is thought to be explained by the sensitivity of Treponema pallidum sub-species pertenue to relative cool and dryness and may explain why skin lesions are seen more often in the rainy season 6. Children serve as the primary reservoir for yaws, as the condition is transmitted from person to person via direct contact. By age group, the population considered to be at risk includes 23 million who are 14 years of age or younger and 11 million who are between the ages of 16 and 24 years. Approximately 75% of those affected by yaws are children younger than 15 years, with the peak incidence occurring between the ages of 6 and 10 years 7.

Treatment of yaws involves a single dose of penicillin, or 3 weekly doses for later stage disease. It is rare for the disease to return.

People who live in the same house with someone who is infected should be examined for yaws and treated if they are infected.

See your health care provider if:

- You or your child has sores on the skin or bone that don’t go away.

- You have stayed in tropical areas where yaws is known to occur.

Causes of yaws

Yaws is an infection caused by Treponema pallidum sub-species pertenue, a slender spirochete that is serologically indistinguishable from the spirochete Treponema pallidum bacteria. Yaws is closely related to the bacterium that causes syphilis, but this form of the bacterium is not sexually transmitted. Yaws mainly affects children in rural, warm, tropical areas, such as, Africa, Western Pacific islands, and Southeast Asia.

Yaws is transmitted by direct contact with the skin sores of infected people.

As with the other nonvenereal treponematoses, yaws is not found in urban centers, is not sexually transmitted, and is not congenitally acquired. The major route of infection is through direct person-to-person contact, and the treponemes associated with yaws are located primarily in the epidermis. Children serve as the primary reservoir for yaws, spreading the disease via skin-to-skin and skin-to–mucous membrane contact.

During the incubation period, Treponema pallidum pertenue invades the subcutaneous lymphatics and disseminates hematogenously. The ulcerative skin lesions that develop early in the disease course are teeming with spirochetes, which can be transmitted via direct skin-to-skin contact and via breaks in the skin due to trauma, bites, or excoriations. Agmon-Levin et al 8 suggested that the antitreponemal antibodies that build up in certain populations may also be protective for atherosclerosis while also being pathogenic for yaws.

Yaws stages

Yaws, like syphilis, has been classified into the following four stages:

- Primary stage, in which the initial yaws lesion develops at the inoculation site

- Secondary stage, in which widespread dissemination of treponemes results in multiple skin lesions that are similar to the primary yaws lesion

- Latent stage, in which symptoms are usually absent but skin lesions can relapse

- Tertiary stage, in which bone, joint, and soft tissue deformities may occur

Cutaneous lesions characterize the primary and secondary stages of yaws. The tertiary stage of yaws may involve the skin, bones, and joints.

Another classification distinguishes early yaws from late yaws. Early yaws includes the primary and secondary stages and is characterized by the presence of contagious skin lesions. Late yaws includes the tertiary stage, when lesions are not contagious.

Primary yaws

A papule appears at the inoculation site after about 21 days (range 9–90) 1. This ‘Mother Yaw’ may evolve either into an exudative papilloma, 2–5 cm in size or degenerate to form a single, non-tender ulcer (Figures 1 and 2) covered by a yellow crust. The legs and ankles are the commonest sites affected, but lesions may occur on the face, buttocks, arms or hands 9. ‘Split-papules’ may occur at the angle of the mouth 1. Regional lymphadenopathy is common. In contrast to syphilis, genital lesions are rare. Primary lesions are indolent and take 3–6 months to heal, more often leaving a pigmented scar 10. As in syphilis 11, the primary lesion is still present when signs of secondary yaws develop in about 9–15% of patients 12.

Figure 1. Primary yaws (papilloma of primary yaws)

Figure 2. Primary yaws (ulcer of primary yaws)

Secondary yaws

Hematogenous and lymphatic spread of treponemes produces secondary lesions, most commonly one to two months (but up to 24 months) after the primary lesion. General malaise and lymphadenopathy may occur. The most florid manifestations of secondary yaws occur in skin and bone 9.

Skin

The rash begins as pinhead-size papules, which develop a pustular or crusted appearance and may persist for weeks. If the crust is removed a raspberry-like appearance may be revealed. Sometimes papules enlarge and coalesce into cauliflower-like lesions, most frequently on the face, trunk, genitalia and buttocks. Scaly macules may be seen (Figures 3 and 4). Lesions in warm, moist areas may resemble condylomata lata of syphilis.

The skin lesions of early yaws are often itchy and the Koebner phenomenon has been observed. Mixed papular and macular lesions are often seen in individual patients. Secondary skin lesions may heal even without treatment, with or without scarring.

Squamous macular or plantar yaws can resemble secondary syphilis 1. Lesions on the soles of the feet may become hyperkeratotic, cracked, discolored or secondarily infected. This can result in pain and a crab-like gait 13. Mucous membrane involvement, most commonly nasal, was reported in less than 0.5% of cases in American Samoa 14.

Figure 3. Secondary yaws (multiple small ulcerative lesions)

Figure 4. Secondary yaws (maculo-papular lesions with scaling)

Bones

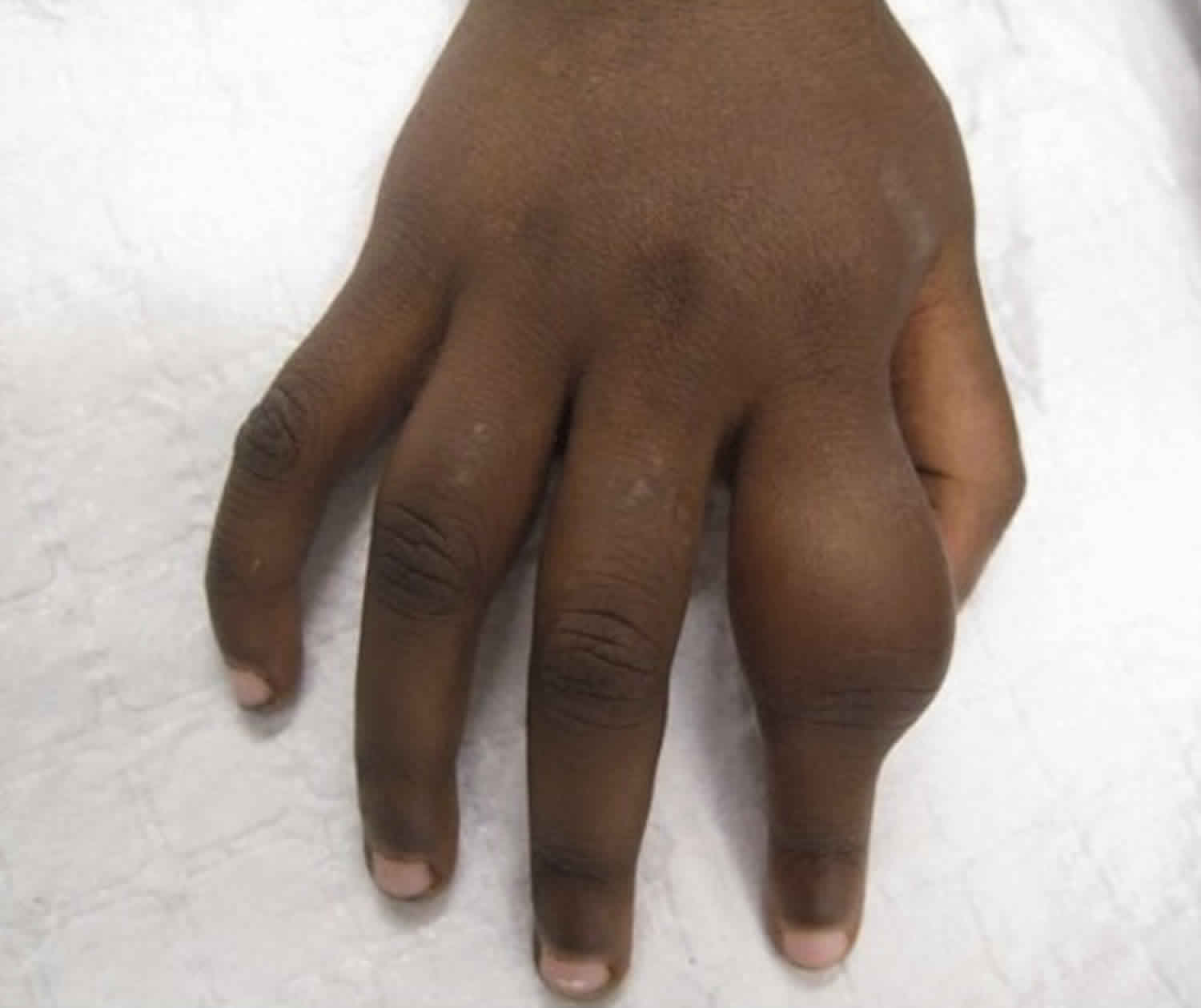

Secondary yaws typically causes osteoperiostitis of multiple bones. Involvement of long bones may cause nocturnal pain and visible periosteal thickening (Figures 6). Involvement of the proximal phalanges of the fingers manifests as polydactylitis. This contrasts with late yaws in which mono-dactylitis is typical. One study from Papua New Guinea 9 reported joint pains in 75% of children with secondary yaws.

Figure 5. Secondary yaws (dactylitis or osteoperiostitis)

Latent yaws

Individuals with latent yaws have reactive serological tests but no clinical signs. It is not known how many patients are infected without developing clinical disease. Patients with primary and secondary yaws may pass into a period of latency after resolution of clinical signs. As in syphilis, infectious relapses can occur, most commonly up to five years (rarely up to 10 years) after infection 15. Relapsing lesions tend to occur around the axillae (armpits), anus and mouth.

Tertiary yaws

Tertiary yaws is thought to occur in about 10% of untreated patients, although its manifestations are rare in the modern era. The skin is most commonly affected. Hyperkeratosis of palms and soles and plaques may occur. Nodules may form near joints and ulcerate, causing tissue necrosis 6. ‘Sabre tibia’ results from chronic osteoperiostitis. Gangosa or rhinopharyngitis mutilans denotes mutilating facial ulceration of the palate and nasopharynx secondary to osteitis. Goundou was a rare complication even when yaws was hyperendemic and is characterised by exostoses of the maxillary bones 16.

Cardiovascular yaws

Although the consensus is that yaws does not cause cardiovascular disease, this view has been challenged. Post-mortem studies have found evidence of aortitis in patients with yaws.22 Histologically these lesions are similar to those found in tertiary syphilis. Despite these studies, definitive evidence of cardiovascular disease in yaws is lacking.

Neurological yaws

The consensus that yaws does not cause neurological disease1 has also been challenged by studies that found neuro-ophthalmic 17 and CSF abnormalities 18 in patients with yaws. As with cardiovascular disease definitive evidence for a causal role of yaws in neurological disease remains absent.

Prevention of yaws

There is no vaccine for yaws. Health education and improvement in personal hygiene are essential components to reduce transmission. Contacts of patients with yaws should receive empiric treatment.

The eradication approach consists of mass treatment also called total community treatment, in which oral azithromycin (30 mg/kg, maximum 2 g) is administered to the entire population (minimum 90% coverage) in areas known to harbour yaws. Two or three rounds of mass treatment may interrupt transmission but studies are in progress to determine the optimum number of rounds.

Three criteria for eradication of yaws are:

- absence of new serologically confirmed indigenous cases for 3 consecutive years;

- absence of any case proven by polymerase chain reaction (PCR); and

- absence of evidence of transmission for 3 continuous years measured with sero-surveys among children aged 1–5 years.

Yaws symptoms

About 2 to 4 weeks after infection, the person develops a sore called a “mother yaw” where bacteria entered the skin. The sore may be tan or reddish and looks like a raspberry. It is most often painless, but does cause itching.

The sores may last for months. More sores may appear shortly before or after the mother yaw heals. Scratching the sore can spread the bacteria from the mother yaw to uninfected skin. Eventually, the skin sores heal.

Other symptoms include:

- Bone pain

- Scarring of the skin

- Swelling of the bones and fingers

In the advanced stage, sores on the skin and bones can lead to severe disfigurement and disability. This occurs in up to 1 in 5 people who do not get antibiotic treatment.

Yaws and pregnancy

While there is no laboratory evidence that Treponema pallidum sub-species pertenue can cause congenital yaws, there are anecdotal reports 19. Most were published when serodiagnosis relied on non-treponemal tests and before treponemal IgM testing of neonates was feasible 14.

Yaws and HIV

There are no published data on the interaction between HIV and yaws. It is possible that patients with latent yaws might develop relapsing disease with increasing immune damage 20. There are also no data on the impact on other sexually transmitted infections (STIs), although given the low rates of genital lesions and that the disease predominantly occurs in children it might be anticipated that any effect would be minimal.

Yaws complications

Yaws may damage the skin and bones. It can affect a person’s appearance and ability to move. It can also cause deformities of the legs, nose, palate, and upper jaw.

Yaws diagnosis

Physicians working in endemic areas usually make a presumptive diagnosis of yaws based on clinical and epidemiological features, with or without confirmatory blood tests. However, because syphilis and yaws co-exist in many tropical regions, and serology cannot distinguish between treponemal sub-species, it may be impossible to identify with certainty the causative organism. There are reports of yaws presenting in non-endemic countries 21.

There is no blood test for yaws. However, the blood test for syphilis is often positive in people with yaws because the bacteria that cause these two conditions are closely related.

A sample from a skin sore is examined under a special type of microscope (darkfield examination).

Dark ground microscopy

Spirochaetes were first observed in yaws ulcers in 1905 22, the year in which Treponema pallidum sub-species pallidum was identified in a lymph gland of a patient with syphilis. Treponema pallidum sub-species pertenue is morphologically identical to Treponema pallidum sub-species pallidum. As Treponema pallidum sub-species are only 0.3 µm wide and 6–20 µm in length, dark ground microscopy is required for visualisation. Samples from primary and secondary yaws lesions are obtained as described for syphilis.

Polymerase chain reaction

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing of samples can identify Treponema pallidum but current PCR protocols do not distinguish between sub-species 9. Treponema pallidum sub-species pertenue has been identified to sub-species level using real-time PCR and DNA sequencing in a child from Congo with a pruritic skin eruption 21, but few clinicians have access to such techniques.

Serology

While serological tests are the bedrock of yaws diagnosis they cannot distinguish between sub-species of Treponema pallidum 23.

Non-treponemal (cardiolipin) tests

The venereal disease research laboratory (VDRL) and rapid plasma reagin (RPR) tests use an antigen of cardiolipin, lecithin and cholesterol. Patient-derived antibodies produced against lipid in the cell surface of Treponema pallidum react with antigen to cause visible flocculation. The VDRL is read microscopically whereas the RPR can be read with the naked eye. Although non-specific, VDRL/RPR titres best reflect disease activity. Titres fall after treatment and may become zero, especially after treatment of early infection 24. RPR titres are generally higher in primary than secondary yaws 1.

Treponemal tests

These include the Treponema pallidum hemagglutination (TPHA) and the Treponema pallidum particle agglutination (TPPA) tests. They are more specific than cardiolipin tests and usually remain positive after treatment.

Point-of-care tests have proved useful in syphilis and results of an initial study in Papua New Guinea suggest they may also be of value in the diagnosis of yaws with good sensitivity and specificity 25. Further studies of these tests in yaws are in progress.

Histology

In early yaws there is marked epidermal hyperplasia and papillomatosis, often with focal spongiosis 26. Neutrophils accumulate in the epidermis, causing microabscesses. A dense dermal infiltrate of plasma cells is seen 27. In contrast with syphilis, there is little endothelial cell proliferation or vascular obliteration 27. Treponema pallidum can be identified in tissue sections using Warthin-Starry or Levaditi silver stains. While Treponema pallidum sub-species pertenue is found mainly in the epidermis, Treponema pallidum sub-species pallidum is identified more in the dermis 28. Direct and indirect immunofluorescence and immunoperoxidase tests using specific polyclonal antibodies to Treponema pallidum can also be used with histology specimens 29.

Radiology

Bone involvement may be revealed by radiographs even when clinical signs are absent 30.

Yaws treatment

Benzathine penicillin-G has been the mainstay of treatment for yaws for over 60 years. Lower doses are used compared to syphilis with a recommended dose of 0.6 MU for children (under 10) and 1.2 MU for older children and adults. In a recent single-centre randomised controlled trial, one dose of azithromycin 30 mg/kg was shown to be equivalent to penicillin in patients with primary and secondary yaws, with a cure rate of approximately 95% 31. No other treatment strategies are supported by randomized controlled trials although data from case series suggest oral penicillin can be successful 32.

Based on these findings, azithromycin is now central to the WHO eradication plan for yaws, which aims to employ community mass treatment in endemic regions. WHO plan to have no further cases of active yaws worldwide by 2017 and to confirm eradication by 2020 33. Despite this optimism there are several barriers to a successful eradication programme including a lack of accurate epidemiological data from many countries where yaws is reported, the absence of dedicated funding for eradication efforts and a concern that resistance to azithromycin, well described in syphilis 34, will emerge in yaws. Monitoring for this during the eradication programme will be essential. This ambitious plan will require considerable input from NGOs, academic institutions and policy makers.

Response to treatment

Treponemes disappear from lesions within 8–10 hours of treatment with penicillin. Skin lesions begin to heal within 2–4 weeks. In patients with secondary yaws, joint pains may begin to improve within as little as 48 hours 35. Bone changes are reversible if treated early enough. Following successful treatment the RPR declines and at 12 months up to 90% of individuals have either a four-fold reduction in RPR or become seronegative 36. Failure of skin lesions to heal or the RPR to drop should be considered treatment failure and an indication for repeat treatment. In endemic settings treatment failure is more common in individuals from higher prevalence communities 37. Whether this represents true treatment failure or re-infection is unclear.

The authors of a study in Papua New Guinea reported failure of yaws treatment with penicillin, which they attributed to bacterial resistance, although no laboratory evidence of this was available 38.

Yaws prognosis

If treated in its early stages, yaws can be cured. Skin lesions may take several months to heal.

By its late stage, yaws may have already caused damage to the skin and bones. It may not be fully reversible, even with treatment.

Unless treated, yaws can become a chronic, relapsing disease after 5-15 years, with skin, bone, and joint involvement. In most patients, yaws remains limited to the skin, but early bone and joint involvement can occur. Although yaws lesions disappear spontaneously, secondary bacterial infections and scarring are common complications.

In 10% of yaws cases, patients enter a late stage (tertiary stage) characterized by destructive cutaneous lesions and severely deforming bone and joint lesions. Tissue damage occurring in late yaws is irreversible. Neurologic and ophthalmologic involvement may also occur. Relapses may occur at intervals of up to 5 years after infection.

- Perine, Peter L, Hopkins, Donald R, Niemel, Paul L. A, St. John, Ronald, Causse, Georges. et al. (1984). Handbook of endemic treponematoses : yaws, endemic syphilis and pinta / Peter L. Perine and Donald R. Hopkins, Paul L. A. Niemel, Ronald K. St. John, Georges Causse and G. M. Antal. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/37178[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Marks M, Lebari D, Solomon AW, Higgins SP. Yaws. Int J STD AIDS. 2015;26(10):696–703. doi:10.1177/0956462414549036 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4655361[↩][↩]

- Yaws eradication: past efforts and future perspectives. https://www.who.int/bulletin/volumes/86/7/08-055608/en/[↩]

- Consultation on yaws elimination 5-7 March 2012, WHO Headquarters, Geneva, Room M505. https://www.who.int/neglected_diseases/NTD_RoadMap_2012_Fullversion.pdf[↩]

- Kazadi WM, Asiedu KB, Agana N, et al. Epidemiology of yaws: an update. Clin Epidemiol 2014; 6: 119–128.[↩]

- Hackett CJ. Extent and nature of the yaws problem in Africa. Bull World Health Organ 1953; 8: 127–182.[↩][↩]

- Maurice J. WHO plans new yaws eradication campaign. Lancet. 2012 Apr 14. 379(9824):1377-8.[↩]

- Agmon-Levin N, Bat-sheva PK, Barzilai O, et al. Antitreponemal antibodies leading to autoantibody production and protection from atherosclerosis in Kitavans from Papua New Guinea. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2009 Sep. 1173:675-82.[↩]

- Mitjà O, Hays R, Lelngei F, et al. Challenges in recognition and diagnosis of yaws in children in Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2011; 85: 113–116.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Sehgal VN. Leg ulcers caused by yaws and endemic syphilis. Clin Dermatol 1990; 8: 166–174.[↩]

- Eccleston K, Collins L, Higgins SP. Primary syphilis. Int J STD AIDS 2008; 19: 145–151.[↩]

- Powell A. Framboesia: history of its introduction into India; with personal observations of over 200 initial lesions. Proc R Soc Med 1923; 16: 15–42.[↩]

- Gip LS. Yaws revisited. Med J Malaysia 1989; 44: 307–311.[↩]

- Hunt D, Johnson AL. Yaws, a study based on over 2,000 cases treated in American Samoa. US Nav Med Bull 1923; 18: 599–607.[↩][↩]

- Engelkens HJ, Vuzevski VD, Stolz E. Nonvenereal treponematoses in tropical countries. Clin Dermatol 1999; 17: 143–152. discussion 105–106.[↩]

- Martinez SA, Mouney DF. Treponemal infections of the head and neck. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 1982; 15: 613–620.[↩]

- Smith JL. Neuro-ophthalmological study of late yaws. I. An introduction to yaws. Br J Vener Dis 1971; 47: 223–225.[↩]

- Hewer TF. Some observations on yaws and syphilis in the Southern Sudan. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg 1934; 27: 593–608.[↩]

- Engelhardt HK. A study of yaws (does congenital yaws occur?). J Trop Med Hyg 1959; 62: 238–240.[↩]

- Hay PE, Tam FW, Kitchen VS, et al. Gummatous lesions in men infected with human immunodeficiency virus and syphilis. Genitourin Med 1990; 66: 374–379.[↩]

- Pillay A, Chen C-Y, Reynolds MG, et al. Laboratory-confirmed case of yaws in a 10-year-old boy from the Republic of the Congo. J Clin Microbiol 2011; 49: 4013–4015.[↩][↩]

- Castellani A. On the presence of spirochaetes in two cases of ulcerated parangi (Yaws). Br Med J 1905; 2: 1280–1280.[↩]

- De Caprariis PJ, Della-Latta P. Serologic cross-reactivity of syphilis, yaws, and pinta. Am Fam Physician 2013; 87: 80–80.[↩]

- Romanowski B, Sutherland R, Fick GH, et al. Serologic response to treatment of infectious syphilis. Ann Intern Med 1991; 114: 1005–1009.[↩]

- Ayove T, Houniei W, Wangnapi R, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of a rapid point-of-care test for active yaws: a comparative study. Lancet Glob Health 2014; 2: e415–e421.[↩]

- Williams HU. Pathology of yaws especially the relation of yaws to syphilis. Arch Pathol 1935; 20: 596–630.[↩]

- Hasselmann CM. Comparative studies on the histo-pathology of syphilis, yaws, and pinta. Br J Vener Dis 1957; 33: 5–12.[↩][↩]

- Hovind-Hougen K, Birch-Andersen A, Jensen H-JS. Ultrastructure of cells of Treponema pertenue obtained from experimentally infected hamsters. Acta Pathol Microbiol Scand [B] 1976; 84: 101–108.[↩]

- Beckett J, Bigbec J. Immunoperoxidase localization of Treponema pallidum: its use in formaldehyde-fixed and paraffin-embedded tissue sections. Arch Pathol Lab Med 1979; 103: 135–138.[↩]

- Mitjà O, Hays R, Ipai A, et al. Osteoperiostitis in early yaws: case series and literature review. Clin Infect Dis 2011; 52: 771–774.[↩]

- Mitjà O, Hays R, Ipai A, et al. Single-dose azithromycin versus benzathine benzylpenicillin for treatment of yaws in children in Papua New Guinea: an open-label, non-inferiority, randomised trial. Lancet 2012; 379: 342–347.[↩]

- Scolnik D, Aronson L, Lovinsky R, et al. Efficacy of a targeted, oral penicillin-based yaws control program among children living in rural South America. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am 2003; 36: 1232–1238.[↩]

- Maurice J. Neglected tropical diseases. Oral antibiotic raises hopes of eradicating yaws. Science 2014; 344: 142–142.[↩]

- Lukehart SA, Godornes C, Molini BJ, et al. Macrolide resistance in Treponema pallidum in the United States and Ireland. N Engl J Med 2004; 351: 154–158.[↩]

- Rein CR. Treatment of yaws in the Haitian peasant. J Natl Med Assoc 1949; 41: 60–65.[↩]

- Li HY, Soebekti R. Serological study of yaws in Java. Bull World Health Organ 1955; 12: 905–943.[↩]

- Mitjà O, Hays R, Ipai A, et al. Outcome predictors in treatment of yaws. Emerg Infect Dis 2011; 17: 1083–1085.[↩]

- Backhouse JL, Hudson BJ, Hamilton PA, et al. Failure of penicillin treatment of yaws on Karkar Island, Papua New Guinea. Am J Trop Med Hyg 1998; 59: 388–392.[↩]