What is yersinia pestis

Yersinia pestis is a zoonotic bacteria that causes plague or the Black Death during medieval times, that is most commonly transmitted through fleas that feed on infected rodents. Yersinia pestis is a Gram-negative, non-motile, non-spore-forming coccobacillus that is also a facultative anaerobe 1. Yersinia pestis, a zoonotic bacteria, usually found in small mammals and their fleas and it is transmitted between animals from their fleas. Humans usually get plague after being bitten by a rodent flea that is infected with the Yersinia pestis bacterium or by handling an animal infected with plague or through direct contact with infected materials or by inhalation. Plague can be a very severe disease in people, particularly in its septicemic and pneumonic forms, with a case-fatality ratio of 30%-100% if left untreated 2. Plague is infamous for killing more than 50 million people in Europe during the fourteenth century. Without proper antibiotic treatment, infection by Yersinia pestis led to death within a few days. Today, plague is easily treated with antibiotics and the use of standard precautions to prevent acquiring infection. Without prompt treatment, plague can cause serious illness or death, with a case-fatality ratio of 30% to 100% if left untreated.

As an animal disease, plague is found in all continents, except Oceania. There is a risk of human plague wherever the presence of plague natural foci (the bacteria, an animal reservoir and a vector) and human population co-exist.

Humans are infected through the bite of an infected flea or by inhalation of bacteria-infested droplets. The infection exists in three major plague forms: bubonic, septicemic, and pneumonic. The bubonic plague is the most common form of infection and targets the victim’s lymphatic system. After being taken up by macrophages, the bacteria proliferate in the affected lymph nodes, causing inflammation and swelling to occur, i.e., buboes. The septicemic plague courses through the body via the bloodstream, disseminating from infected lymph nodes. Victims of septicemic plague are usually covered with black patches due to hemorrhages throughout the skin, leading to its “Black Death” nickname. Occasionally, Yersinia pestis causes infection of the lungs, resulting in the pneumonic plague. What distinguishes the plague from other invasive, systemic, and infectious diseases is that Yersinia pestis bacteria replicate extracellularly in tissues following lysis of macrophages and hence, the Yersinia pestis bacteria population in the affected host is enormous. Victims were not likely to survive plague without antibiotic treatment. In today’s society, infection usually occurs in summer when the chances of being bitten by a flea are higher in warmer weather 3. Presently, human plague infections continue to occur in the western United States, but significantly more cases occur in parts of Africa and Asia.

Plague epidemics have occurred in Africa, Asia, and South America; but since the 1990s, most human cases have occurred in Africa. The three most endemic countries are the Democratic Republic of Congo, Madagascar, and Peru. In Madagascar cases of bubonic plague are reported nearly every year, during the epidemic season (between September and April) 4.

Confirmation of plague requires lab testing. The best practice is to identify Yersinia pestis from a sample of pus from a bubo, blood or sputum. A specific Yersinia pestis antigen can be detected by different techniques.

Yersinia pestis key facts 4:

- Plague is caused by the bacteria Yersinia pestis, a zoonotic bacteria usually found in small mammals and their fleas.

- People infected with Yersinia pestis often develop symptoms after an incubation period of one to seven days.

- There are two main clinical forms of plague infection: bubonic and pneumonic. Bubonic plague is the most common form and is characterized by painful swollen lymph nodes or ‘buboes’.

- Plague is transmitted between animals and humans by the bite of infected fleas, direct contact with infected tissues, and inhalation of infected respiratory droplets.

- Plague can be a very severe disease in people, with a case-fatality ratio of 30% to 60% for the bubonic type, and is always fatal for the pneumonic kind when left untreated.

- Antibiotic treatment is effective against plague bacteria, so early diagnosis and early treatment can save lives.

- From 2010 to 2015 there were 3248 cases reported worldwide, including 584 deaths.

- Currently, the three most endemic countries are the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Madagascar, and Peru.

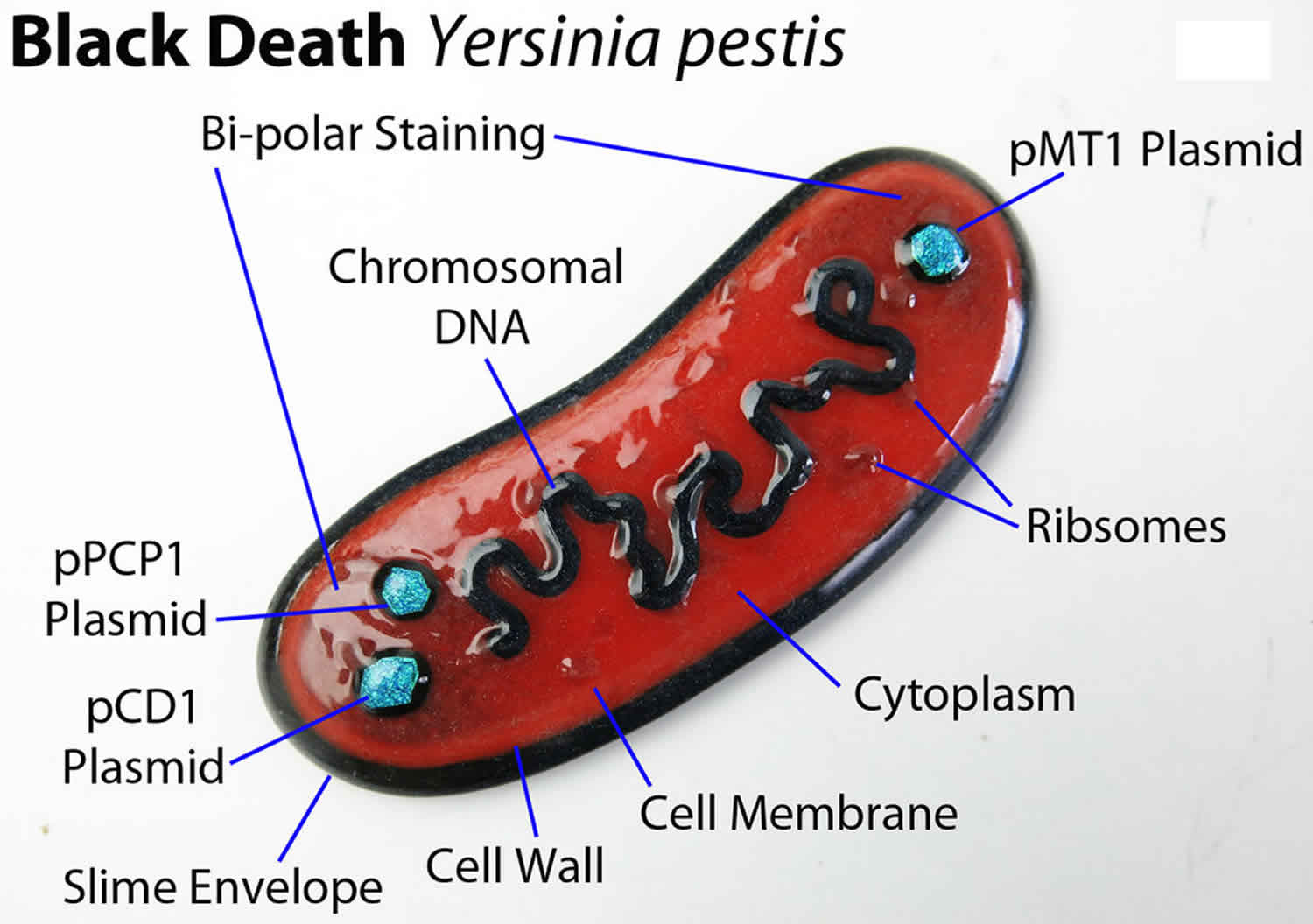

Figure 1. Yersinia pestis bacteria

Figure 2. Global distribution of natural plague foci as of March 2016

Figure 3. Reported Cases of Human Plague in United States 1970-2016

Yersinia pestis transmission

The organism that causes plague, Yersinia pestis, lives in small rodents found most commonly in rural and semirural areas of Africa, Asia and the United States. The organism is transmitted to humans who are bitten by fleas that have fed on infected rodents or by humans handling infected animals. Yersinia pestis, the plague bacteria can be transmitted to humans in the following ways:

Flea bites

Yersinia pestis bacteria are most often transmitted by the bite of an infected flea. During plague epizootics, many rodents die, causing hungry fleas to seek other sources of blood. People and animals that visit places where rodents have recently died from plague are at risk of being infected from flea bites. Dogs and cats may also bring plague-infected fleas into the home. Flea bite exposure may result in primary bubonic plague or septicemic plague.

Contact with contaminated fluid or tissue

Humans can become infected when handling tissue or body fluids of a plague-infected animal. For example, a hunter skinning a rabbit or other infected animal without using proper precautions could become infected with Yersinia pestis bacteria. This form of exposure most commonly results in bubonic plague or septicemic plague.

Infectious droplets

When a person has plague pneumonia, they may cough droplets containing the Yersinia pestis bacteria into air. If these Yersinia pestis bacteria-containing droplets are breathed in by another person they can cause pneumonic plague. Typically this requires direct and close contact with the person with pneumonic plague. Transmission of these droplets is the only way that plague can spread between people. This type of spread has not been documented in the United States since 1924, but still occurs with some frequency in developing countries. Cats are particularly susceptible to plague, and can be infected by eating infected rodents. Sick cats pose a risk of transmitting infectious plague droplets to their owners or to veterinarians. Several cases of human plague have occurred in the United States in recent decades as a result of contact with infected cats.

Figure 4. Yersinia pestis transmission

Figure 5. Possible transmission pathways for Yersinia pestis

[Source 5 ]Yersinia pestis life cycle

The bacteria that cause plague, Yersinia pestis, maintain their existence in a cycle involving rodents and their fleas. In urban areas or places with dense rat infestations, the plague bacteria can cycle between rats and their fleas. The last urban outbreak of rat-associated plague in the United States occurred in Los Angeles in 1924-1925.

Since that time, plague has occurred in rural and semi-rural areas of the western United States, primarily in semi-arid upland forests and grasslands where many types of rodent species can be involved. Many types of animals, such as rock squirrels, wood rats, ground squirrels, prairie dogs, chipmunks, mice, voles, and rabbits can be affected by plague. Wild carnivores can become infected by eating other infected animals.

Scientists think that plague bacteria circulate at low rates within populations of certain rodents without causing excessive rodent die-off. These infected animals and their fleas serve as long-term reservoirs for the bacteria. This is called the enzootic cycle.

Occasionally, other species become infected, causing an outbreak among animals, called an epizootic. Humans are usually more at risk during, or shortly after, a plague epizootic. Scientific studies have suggested that epizootics in the southwestern United States are more likely during cooler summers that follow wet winters. Epizootics are most likely in areas with multiple types of rodents living in high densities and in diverse habitats.

Yersinia pestis prevention

Preventive measures include informing people when zoonotic plague is present in their environment and advising them to take precautions against flea bites and not to handle animal carcasses. Generally people should be advised to avoid direct contact with infected body fluids and tissues. When handling potentially infected patients and collecting specimens, standard precautions should apply.

- Reduce rodent habitat around your home, work place, and recreational areas. Remove brush, rock piles, junk, cluttered firewood, and possible rodent food supplies, such as pet and wild animal food. Make your home and outbuildings rodent-proof.

- Wear gloves if you are handling or skinning potentially infected animals to prevent contact between your skin and the plague bacteria. Contact your local health department if you have questions about disposal of dead animals.

- Use repellent if you think you could be exposed to rodent fleas during activities such as camping, hiking, or working outdoors. Products containing DEET can be applied to the skin as well as clothing and products containing permethrin can be applied to clothing (always follow instructions on the label).

- Keep fleas off of your pets by applying flea control products. Animals that roam freely are more likely to come in contact with plague infected animals or fleas and could bring them into homes. If your pet becomes sick, seek care from a veterinarian as soon as possible.

- Do not allow dogs or cats that roam free in endemic areas to sleep on your bed.

Note: A plague vaccine is no longer available in the United States. New plague vaccines are in development but are not expected to be commercially available in the immediate future.

Managing plague outbreaks

- Find and stop the source of infection. Identify the most likely source of infection in the area where the human case(s) was exposed, typically looking for clustered areas with large numbers of small animal deaths. Institute appropriate infection, prevention and control procedures. Institute vector control, then rodent control. Killing rodents before vectors will cause the fleas to jump to new hosts, this is to be avoided.

- Protect health workers. Inform and train them on infection prevention and control. Workers in direct contact with pneumonic plague patients must wear standard precautions and receive a chemoprophylaxis with antibiotics for the duration of seven days or at least as long as they are exposed to infected patients.

- Ensure correct treatment: Verify that patients are being given appropriate antibiotic treatment and that local supplies of antibiotics are adequate.

- Isolate patients with pneumonic plague. Patients should be isolated so as not to infect others via air droplets. Providing masks for pneumonic patients can reduce spread.

- Surveillance: identify and monitor close contacts of pneumonic plague patients and give them a seven-day chemoprophylaxis. Chemoprophylaxis should also be given to household members of bubonic plague patients.

- Obtain specimens which should be carefully collected using appropriate infection, prevention and control procedures and sent to labs for testing.

- Disinfection. Routine hand-washing is recommended with soap and water or use of alcohol hand rub. Larger areas can be disinfected using 10% of diluted household bleach (made fresh daily).

- Ensure safe burial practices. Spraying of face/chest area of suspected pneumonic plague deaths should be discouraged. The area should be covered with a disinfectant-soaked cloth or absorbent material.

Surveillance and control

Surveillance and control requires investigating animal and flea species implicated in the plague cycle in the region and developing environmental management programmes to understand the natural zoonosis of the disease cycle and to limit spread. Active long-term surveillance of animal foci, coupled with a rapid response during animal outbreaks has successfully reduced numbers of human plague outbreaks.

In order to effectively and efficiently manage plague outbreaks it is crucial to have an informed and vigilant health care work force (and community) to quickly diagnose and manage patients with infection, to identify risk factors, to conduct ongoing surveillance, to control vectors and hosts, to confirm diagnosis with laboratory tests, and to communicate findings with appropriate authorities.

Yersinia pestis symptoms

Plague symptoms depend on how the patient was exposed to the plague bacteria. Plague can take different clinical forms, but the most common are bubonic, pneumonic, and septicemic. Additional rare forms of plague include pharyngeal, meningeal, and cutaneous.

People infected with plague usually develop acute febrile disease with other non-specific systemic symptoms after an incubation period of one to seven days, such as sudden onset of fever, chills, head and body aches, and weakness, vomiting and nausea.

Plague is a very severe disease in people, particularly in its septicaemic (systemic infection caused by circulating bacteria in bloodstream) and pneumonic forms, with a case-fatality ratio of 30% to 100% if left untreated. The pneumonic form is invariably fatal unless treated early. It is especially contagious and can trigger severe epidemics through person-to-person contact via droplets in the air.

Bubonic plague

Bubonic plague is the most common primary manifestation of Yersinia pestis infection with patients developing sudden onset of fever, headache, chills, and weakness and one or more swollen, tender and painful lymph nodes (called buboes). A bubo usually occurs in the groin, armpit or cervical lymph nodes. Buboes are often so painful that patients are generally guarded and have restricted movement in the affected region. The incubation period for bubonic plague is usually 2 to 6 days. Bubonic plague usually results from the bite of an infected flea. The bacteria multiply in the lymph node closest to where the bacteria entered the human body. If the patient is not treated with the appropriate antibiotics, the bacteria can spread to other parts of the body.

If bubonic plague is untreated, Yersinia pestis bacteria invade the bloodstream and spread rapidly, causing septicemic plague, and if the lungs are seeded, secondary pneumonic plague. Septicemic and pneumonic plague may also be primary manifestations. A person with pneumonic plague may experience high fever, chills, cough, and breathing difficulty and may expel bloody sputum. If pneumonic plague patients are not given specific antibiotic therapy, the disease can progress rapidly to death.

Although the majority of patients with plague present with a bubo, some may have nonspecific symptoms. For example, septicemic plague can present with prominent gastrointestinal symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain 6.

Septicemic plague

Patients develop fever, chills, extreme weakness, abdominal pain, shock, and possibly bleeding into the skin and other organs. Skin and other tissues may turn black and die, especially on fingers, toes, and the nose. Septicemic plague can occur as the first symptom of plague, or may develop from untreated bubonic plague. This form results from bites of infected fleas or from handling an infected animal.

Pneumonic plague

Pneumonic plague, or lung-based plague, is the most virulent form of plague. Incubation can be as short as 24 hours. Any person with pneumonic plague may transmit the disease via droplets to other humans. Untreated pneumonic plague, if not diagnosed and treated early, can be fatal. However, recovery rates are high if detected and treated in time (within 24 hours of onset of symptoms).

Patients develop fever, headache, weakness, and a rapidly developing pneumonia with shortness of breath, chest pain, cough, and sometimes bloody or watery mucous. Pneumonic plague may develop from inhaling infectious droplets or may develop from untreated bubonic or septicemic plague after the bacteria spread to the lungs. The pneumonia may cause respiratory failure and shock. Pneumonic plague is the most serious form of the disease and is the only form of plague that can be spread from person to person (by infectious droplets).

Plague is a serious illness. If you are experiencing symptoms like those listed here, seek immediate medical attention. Prompt treatment with the correct medications is critical to prevent complications or death.

Figure 6. Yersinia pestis symptoms

Yersinia pestis in the United States

Plague was first introduced into the United States in 1900, by rat–infested steamships that had sailed from affected areas, mostly from Asia. Epidemics occurred in port cities. The last urban plague epidemic in the United States occurred in Los Angeles from 1924 through 1925. Plague then spread from urban rats to rural rodent species, and became entrenched in many areas of the western United States. Since that time, plague has occurred as scattered cases in rural areas. Most human cases in the United States occur in two regions:

- Northern New Mexico, northern Arizona, and southern Colorado

- California, southern Oregon, and far western Nevada

Over 80% of United States plague cases have been the bubonic form. In recent decades, an average of seven human plague cases have been reported each year (range: 1–17 cases per year). Plague has occurred in people of all ages (infants up to age 96), though 50% of cases occur in people ages 12–45. It occurs in both men and women, though historically is slightly more common among men, probably because of increased outdoor activities that put them at higher risk.

Yersinia pestis diagnosis

Plague is a plausible diagnosis for people who are sick and live in, or have recently traveled to, the western United States or any other plague-endemic area. The most common sign of bubonic plague is the rapid development of a swollen and painful lymph gland called a bubo. A known flea bite or the presence of a bubo may help a doctor to consider plague as a cause of the illness.

In many cases, particularly in septicemic and pneumonic plague, there are no obvious signs that indicate plague. Diagnosis is made by taking samples from the patient, especially blood or part of a swollen lymph gland, and submitting them for laboratory testing. Once plague has been identified as a possible cause of the illness, appropriate treatment should begin immediately.

Appropriate diagnostic samples include blood cultures, lymph node aspirates if possible, and/or sputum, if indicated. Drug therapy should begin as soon as possible after the laboratory specimens are taken. If plague is suspected, local and state health departments should be notified immediately. If the patient has pneumonic signs, he/she should also be isolated and placed on droplet precautions.

Diagnostic Testing

If plague is suspected, pre-treatment specimens should be taken if possible, but treatment should not be delayed. Specimens should be obtained from appropriate sites for isolating the bacteria, and depend on the clinical presentation:

- Lymph node aspirate: An affected bubo should contain numerous organisms that can be evaluated microscopically and by culture.

- Blood cultures: Organisms may be seen in blood smears if the patient is septicemic. Blood smears taken from suspected bubonic plague patients early in the course of illness are usually negative for bacteria by microscopic examination but may be positive by culture.

- Sputum: Culture is possible from sputum of very ill pneumonic patients; however, blood is usually culture-positive at this time as well.

- Bronchial/tracheal washing may be taken from suspected pneumonic plague patients; throat specimens are not ideal for isolation of plague since they often contain many other bacteria that can mask the presence of plague.

- In cases where live organisms are unculturable (such as postmortem), lymphoid, spleen, lung, and liver tissue or bone marrow samples may yield evidence of plague infection by direct detection methods such as direct fluorescent antibody (DFA) or polymerase chain reaction (PCR).

Yersinia pestis may be identified microscopically by examination of Gram, Wright, Giemsa, or Wayson’s stained smears of peripheral blood, sputum, or lymph node specimen.Visualization of bipolar-staining, ovoid, Gram-negative organisms with a “safety pin” appearance permits a rapid presumptive diagnosis of plague.

If cultures yield negative results, and plague is still suspected, serologic testing is possible to confirm the diagnosis. One serum specimen should be taken as early in the illness as possible, followed by a convalescent sample 4-6 weeks or more after disease onset.

Yersinia pestis treatment

Recommended antibiotic treatment for plague

Begin appropriate IV therapy as soon as plague is suspected. Gentamicin and fluoroquinolones are typically first-line treatments in the United States. Duration of treatment is 10 to 14 days, or until 2 days after fever subsides. Oral therapy may be substituted once the patient improves.

The regimens listed below are guidelines only and may need to be adjusted depending on a patient’s age, medical history, underlying health conditions, or allergies. Please use clinical judgment.

Table 1. Recommended antibiotic treatment of adults for plague

| Antibiotic | Dose | Route of administration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomycin | 1 g twice daily | IM | Not widely available in the US |

| Gentamicin | 5 mg/kg once daily, or 2 mg/kg loading dose followed by 1.7 mg/kg every 8 hours | IM or IV | Not FDA approved but considered an effective alternative to streptomycin 7. Due to poor abscess penetration, consider alternative or dual therapy for patients with bubonic disease. |

| Levofloxacin | 500 mg once daily | IV or po | Bactericidal. FDA approved based on animal studies but limited clinical experience treating human plague. A higher dose (750 mg) may be used if clinically indicated. |

| Ciprofloxacin | 400 mg every 8-12 hours | IV | Bactericidal. FDA approved based on animal studies but limited clinical experience treating human plague. |

| 500-750 mg twice daily | po | ||

| Doxycycline | 100 mg twice daily or 200 mg once daily | IV or po | Bacteriostatic, but effective in a randomized trial when compared to gentamicin 8 |

| Moxifloxacin | 400 mg once daily | IV or po | |

| Chloramphenicol | 25 mg/kg every 6 hours | IV | Not widely available in the United States. |

Table 2. Recommended antibiotic treatment of children for plague

| Antibiotic | Dose | Route of administration | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Streptomycin | 15 mg/kg twice daily (maximum 2 g/day) | IM | Not widely available in the United States. |

| Gentamicin | 2.5 mg/kg/dose every 8 hours | IM or IV | Not FDA approved but considered an effective alternative to streptomycin 7. Due to poor abscess penetration, consider alternative or dual therapy for patients with bubonic disease. |

| Levofloxacin | 8 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours (max 250 mg per dose) | IV or po | Bactericidal. This dosing regimen is based on the levofloxacin package insert and is recommended for pediatric patients <50 kg and ≥6 months of age. FDA approved based on animal studies but limited clinical experience treating human plague. |

| Ciprofloxacin | 15 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours (maximum 400 mg/dose) | IV | Bactericidal. FDA approved based on animal studies but limited clinical experience treating human plague. |

| 20 mg/kg/dose every 12 hours (maximum 500 mg/dose) | po | ||

| Doxycycline | Weight < 45 kg: 2.2 mg/kg twice daily (maximum 100 mg/dose) Weight ≥ 45 kg: same as adult dose | IV or po | Bacteriostatic, but FDA approved and effective in a randomized trial when compared to gentamicin 8. No tooth staining after multiple short courses 10 |

| Chloramphenicol (for children > 2 years) | 25 mg/kg every 6 h (maximum daily dose, 4 g) | IV | Not widely available in the United States |

Table 3. Recommended antibiotic treatment of pregnant women for plague

| Antibiotic | Dose | Route of administration |

| Gentamicin | Same as adult dose | IM or IV |

| Doxycycline | Same as adult dose | IV |

| Ciprofloxacin | Same as adult dose | IV |

Footnote: All recommended antibiotics for plague have relative contraindications for use in children and pregnant women; however, use is justified in life-threatening situations.

[Source 9 ]Post-exposure prophylaxis

Post-exposure prophylaxis is indicated in persons with known exposure to plague, such as close contact with a pneumonic plague patient or direct contact with infected body fluids or tissues. Duration of post-exposure prophylaxis to prevent plague is 7 days. The recommended antibiotic regimens for post-exposure prophylaxis are as follows:

Table 4. Post-exposure prophylaxis

| Preferred agents | Dose | Route of administration | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adults | Doxycycline | 100 mg twice daily | PO |

| Ciprofloxacin | 500 mg twice daily | PO | |

| Children | Doxycycline (for children ≥ 8 years) | Weight < 45 kg: 2.2 mg/kg twice daily (maximum daily dose, 200 mg) Weight ≥ 45 kg: same as adult dose | PO |

| Ciprofloxacin | 20 mg/kg twice daily (maximum daily dose, 1 g) | PO | |

| Pregnant women | Doxycycline | 100 mg twice daily | PO |

| Ciprofloxacin | 500 mg twice daily | PO |

Footnote: Doxycycline and ciprofloxacin are pregnancy categories D and C, respectively. PEP should be given only when the benefits outweigh the risks.

[Source 9 ]- Perry R, Fetherston J. 1997. Yersinia pestis – Etiologic Agent of Plague. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 10(1):35-66.[↩]

- Plague. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/plague/en/[↩]

- Gross L. How the plague bacillus and its transmission through fleas were discovered: reminiscences from my years at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 1995 15;92(17):7609-11.[↩]

- Plague. http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/plague[↩][↩]

- Institute of Medicine (US) Forum on Microbial Threats. Global Climate Change and Extreme Weather Events: Understanding the Contributions to Infectious Disease Emergence: Workshop Summary. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2008. 2, Climate, Ecology, and Infectious Disease. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK45744[↩]

- Human Plague – Four States, 2006. https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm5534a4.htm[↩]

- Boulanger LL, Ettestad P, Fogarty JD, Dennis DT, Romig D, Mertz G. Gentamicin and tetracyclines for the treatment of human plague: Review of 75 cases in New Mexico, 1985–1999. Clin Infect Dis. 2004 38(5):663-669.[↩][↩]

- Mwengee W, Butler T, Mgema S, Mhina G, Almasi Y, Bradley C, Formanik JB, Rochester CG. Treatment of plague with gentamicin or doxycycline in a randomized clinical trial in Tanzania. Clin Infect Dis. 2006 42(5):614-21.[↩][↩]

- Plague – Resources for Clinicians. https://www.cdc.gov/plague/healthcare/clinicians.html[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Todd SR, Dahlgren FS, Traeger MS, Beltrán-Aguilar ED, Marianos DW, Hamilton C, McQuiston JH, Regan JJ. No visible dental staining in children treated with doxycycline for suspected Rocky Mountain spotted fever. J Pediatr. 2015 May;166(5):1246-51.[↩]