Acute interstitial pneumonitis

Acute interstitial pneumonitis sometimes called diffused parenchymal lung diseases, is an umbrella term used for a large group of diseases that cause scarring (fibrosis) of the lungs. The scarring causes stiffness in the lungs which makes it difficult to breathe and get oxygen to the bloodstream. Lung damage from interstitial lung diseases is often irreversible and gets worse over time.

Anyone can get interstitial lung disease, including children. Many things can increase the risk of or cause interstitial lung diseases including genetics, certain medications or medical treatments such as radiation or chemotherapy. Exposure to hazardous materials has been linked to interstitial lung diseases such as asbestosis and hypersensitivity pneumonitis. People with autoimmune diseases such as sarcoidosis or rheumatoid arthritis are also at increased risk of developing an interstitial lung disease. Smoking can not only cause interstitial lung diseases, but can make the condition much worse, which is why anyone diagnosed is strongly encouraged to quit. Unfortunately, in many cases, such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, the causes may be unknown.

Interstitial lung disease incidence rates in the United States have been difficult to determine. Many speculate that the prevalence is far more substantial than formerly described. The reason that the reported prevalence may be so low is because of failure to recognize the disease. interstitial lung disease is a diagnosis of exclusion that requires extensive investigation 1. Now, newer guidelines/classification have made it easier. The estimated incidence is 30 per 100000 per year. The overall prevalence is 80.9 per 100000 per year in males and 67.2 per 100000 per year in females 2. These statistics derived from one of the most important epidemiologic studies, undertaken in Bernalillo County in New Mexico.

The most common symptom of all interstitial lung diseases is shortness of breath. This is often accompanied by a dry cough, chest discomfort, fatigue and occasionally weight loss. In most cases, by the time the symptoms appear lung damage has already been done so it is important to see your doctor immediately. Severe cases that are left untreated can develop life-threatening complications including high blood pressure, heart or respiratory failure.

To diagnose an interstitial lung disease, your doctor will probably order a chest X-ray or CT scan to get a better look at your lungs. A lung function test may be used to measure your total lung capacity, which may have deteriorated due to the interstitial lung disease. In more serious cases, and to diagnose a specific type of interstitial lung disease, more invasive procedures may be needed, such as a bronchoscopy or a lung biopsy.

Treatment for interstitial lung diseases varies depending on the type of interstitial lung disease diagnosed and the severity. Lung damage from interstitial lung diseases is often irreversible and progressive, so treatment normally centers on relieving symptoms, improving quality of life and slowing the disease’s progression. Medications, such as corticosteroids, can be used to decrease inflammation in the lungs. Oxygen therapy is another common treatment because it helps deliver extra oxygen to make breathing easier and lessen complications from low blood oxygen levels, such as heart failure. Pulmonary rehabilitation may also be recommended to improve daily life by giving patients techniques to improve lung efficiency, improve physical endurance and offer emotional support. In the most extreme cases, people with interstitial lung diseases will be recommended for lung transplants.

Acute interstitial pneumonia

Acute interstitial pneumonia encompasses a spectrum of pulmonary disorders characterized by involvement of the lung interstitium in a bilateral, generally symmetric and diffuse fashion 3 and distal airways (bronchioles and alveoli) 4. Acute interstitial pneumonia is an idiopathic interstitial lung disease that is clinically characterized by sudden onset of dyspnea and rapid development of respiratory failure 3. The onset of respiratory symptoms is acute, most often within two weeks. Most acute interstitial pneumonia take place de novo, but sometimes represent an acute exacerbation of chronic lung disease. The clinical presentation of acute interstitial pneumonia comprises rapidly progressive dyspnea, associated sometimes with cough, fever, myalgia and asthenia. Most affected patients are adults, but acute interstitial pneumonia has been reported in a wide age range of patients, including children as young as 7 and in patients over 80 years old, with a mean age at diagnosis of 54 years old 5. No gender preference exists. In comparison, the overall US incidence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis is an estimated 6.8-16.3 per 100,000 person-years, with an increased incidence with advancing age 3.

Chest radiography shows diffuse pulmonary opacities. The associated hypoxemia may be severe enough to cause acute respiratory failure. Underlying etiologies are numerous and variable, particularly in relation to the underlying immune status of the host. Various histopathological entities may be responsible for acute interstitial pneumonia although diffuse alveolar damage is the predominant pattern. Acute interstitial pneumonia is histologically characterized by diffuse alveolar damage with subsequent fibrosis 6. The definition of acute interstitial pneumonia excludes patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) attributable to an identifiable cause, as well as patients with underlying fibrotic lung disease or systemic disorders known to be associated with lung involvement such as connective tissue disease 6. The diagnostic approach to a patient presenting with acute interstitial pneumonia is to try to determine the most likely underlying histopathological pattern and to search for a precise etiology. It relies mainly on a meticulous clinical evaluation and accurate biological investigation, essentially guided by the results of bronchoalveolar lavage performed in an area identified by abnormalities on high resolution computed tomography of the lungs. Initial therapeutic management includes symptomatic measures, broad-spectrum antibiotic treatment adapted to the clinical context, frequently combined with systemic corticosteroid therapy.

Acute interstitial pneumonia causes

By definition, the diagnosis of acute interstitial pneumonia assumes the absence of a specific etiologic agent or inciting event.

Acute interstitial pneumonia symptoms

Most patients describe a upper respiratory infection/viral-like prodrome and a nonproductive cough. A bimodal distribution appears to exist, with about 50% of patients presenting with symptoms of dyspnea within the first week of symptoms and others presenting after at least a month and up to 60 days from the onset of symptoms 5. With rare exception, patients progress rapidly from shortness of breath to hypoxemic respiratory failure that requires prolonged mechanical ventilation.

Acute interstitial pneumonia diagnosis

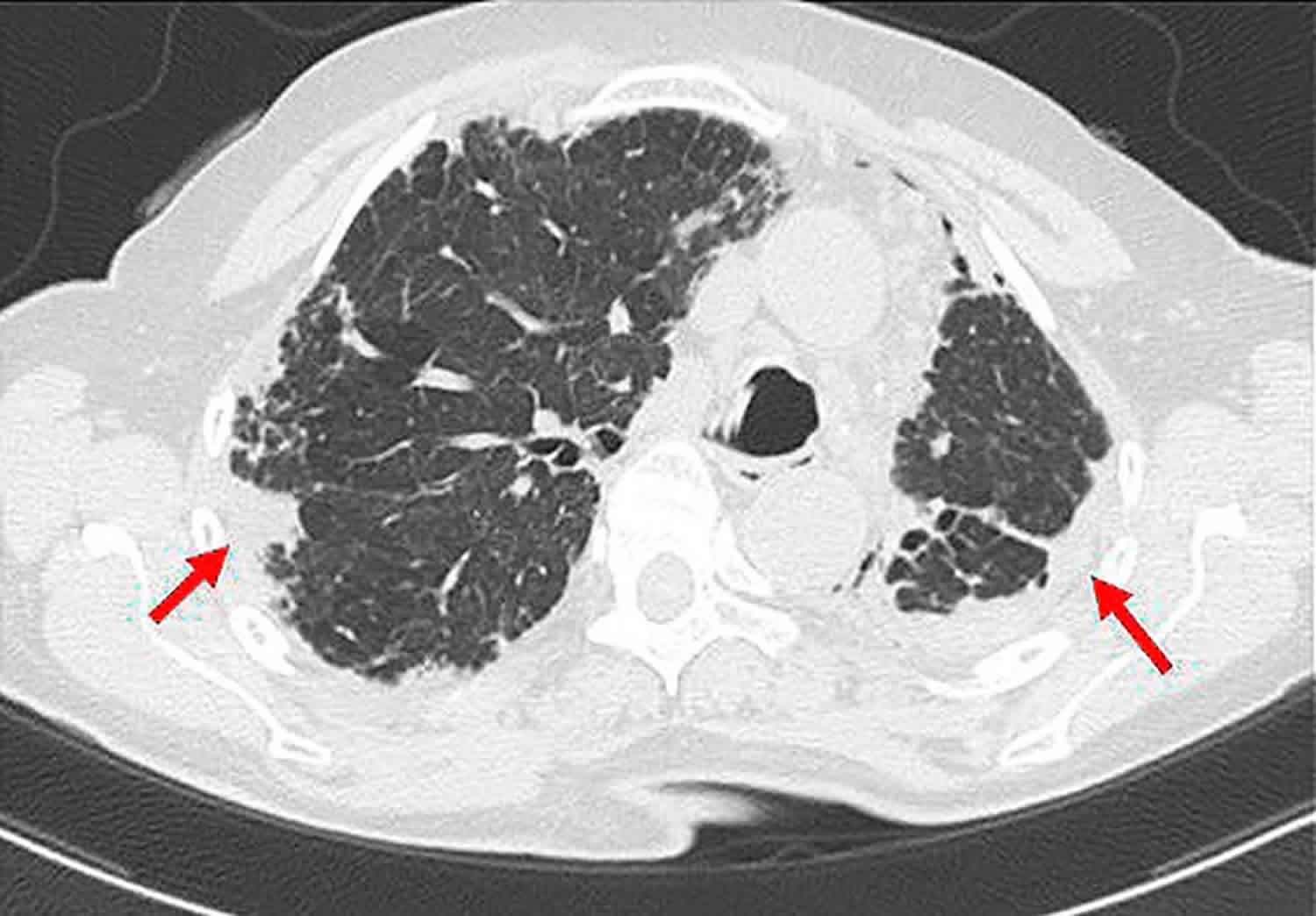

Physical examination and laboratory findings are nonspecific. In the early course of the disease, attention is focused on excluding known causes of acute lung injury by history, physical examination, and ancillary studies. The radiographic findings associated with acute interstitial pneumonia, both in the early and late phase of the disease, overlap with those of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). As in ARDS, the earliest phase begins with a subtle increase in interstitial markings with rapid development of a diffuse alveolar pattern. High-resolution CT (HRCT) scans show bilateral and symmetric, diffuse ground glass and alveolar consolidation opacities. Traction bronchiectasis and bronchiolectasis appear as the disease progresses.

Honeycomb fibrosis may be seen in the later phase of the disease. It has been reported that patients with acute interstitial pneumonia tend to have a more symmetrical and lower zone distribution of abnormalities as well as more honeycombing than patients with ARDS 7. Differences in acute interstitial pneumonia survivors and nonsurvivors have also been reported, with the former group having more ground-glass opacification and less traction deformity of the airways 8. Honeycomb change is not present early in the course of acute interstitial pneumonia, and its identification on HRCT should prompt consideration of pre-existing fibrotic lung disease.

Gross findings

The gross appearance is identical to other patients who die with ARDS and the gross findings correlate with the stage of diffuse alveolar damage. In the early phase, the lungs are firm, heavy, and have a homogeneous dark red (“beefy”) appearance. In later phases, the lungs are extremely heavy with irregular areas of dense consolidation and fibrosis. Cobblestoning of the pleural surface, associated with progressive fibrosis, may exist. Extensive peripheral cyst formation consistent with honeycombing should suggest the possibility of underlying chronic fibrotic lung disease.

Microscopic findings

Transbronchial biopsy may be attempted in the early course of the disease, primarily to exclude other etiologies such as infection. Surgical lung biopsy is performed for similar reasons when the patient is stable enough. The time at which the biopsy is obtained is quite variable but typically occurs after at least 1-2 weeks following the onset of respiratory failure and often after other etiologies have been considered 6.

Biopsy findings from patients with idiopathic interstitial pneumonia may vary on the basis of when the biopsies are performed relative to the onset of acute injury 3. The initial stages show diffuse alveolar damage, usually in the proliferative or organizing phase, although hyaline membrane remnants can be seen 9. The interstitial fibrosis is diffuse, temporally uniform and characterized by extensive fibroblastic and myofibroblastic proliferation with relatively little collagen deposition. The prominence and the uniformity of the fibroblastic/myofibroblastic proliferation distinguishes acute interstitial pneumonia from the other types of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia.

In addition to the spindle cell proliferation that thickens and distorts the alveolar septa, intraluminal polypoid plugs indistinguishable from organizing pneumonia may also be present 9. As in other cases of diffuse alveolar damage, regardless of etiology, prominent type II pneumocyte hyperplasia with cytologic atypia and bronchiolar squamous metaplasia is present.

Organizing thrombi involving small and medium-sized arteries are often present and help to support the diagnosis of acute lung injury. Biopsies that are taken later in the course of the disease show enlarged and remodeled airspaces that resemble the honeycomb change of usual interstitial pneumonia, but fibroblastic proliferation, along with collagen deposition, should still be conspicuous within the walls of the air spaces. As with other interstitial lung diseases, the diagnosis of acute interstitial pneumonia should be rendered within the specific context of a detailed clinical evaluation and with radiographic correlation.

Acute interstitial pneumonia treatment

The mainstay therapy for treatment of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia is corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapies to intercept the inflammatory process within the lungs 10. Right now, nintedanib and pirfenidone are immunosuppressant drugs that have been approved but only in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis 11. Some studies have provided indirect evidence that early therapy within the course of the disease might correlate with therapeutic responsiveness because the lung architecture has not suffered significant derangement. Once fibrosis initiates, there has not been any treatment to reverse that process, but nintedanib can slow disease progression 12. Transplant is the sole treatment modality that can reinstate physiological function in patients.

Acute interstitial pneumonia prognosis

In the intervening years since acute interstitial pneumonia’s formal description in 1986, little progress has been made in the understanding of the disease. Currently, no specific or proven effective treatments for acute interstitial pneumonia exist, management is largely supportive, and multidisciplinary team involvement is best for optimal therapy 3. Broad-spectrum antibiotics, antiviral agents, and high-dose steroids are often administered on an empiric basis. Specific clinical features that would predict survival have not been clearly identified. Similarly, histologic features predictive of survival have not been identified 13.

Although relative differences in the radiographic features of patients with acute interstitial pneumonia and ARDS and acute interstitial pneumonia survivors versus nonsurvivors have been reported, these findings are difficult to extrapolate to prognosis for an individual patient. Survival data are limited and likely subject to some study bias, but the acute case fatality ratio is estimated to be 50% or more 14. Most deaths occur within 1-3 months of diagnosis; whereas median survival for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis patients is about 2-5 years from the time of diagnosis 3. Of those patients who survive, some return to their baseline respiratory function, but a significant proportion will exhibit some degree of functional respiratory impairment. Recurrent episodes of acute interstitial pneumonia have also been described.

In a retrospective study (2000-2012) with 203 of 1625 patients (12.5%) who underwent resection of primary lung cancer and were found to idiopathic interstitial pneumonia, multivariate analyses revealed the following as significant radiologic predictors of 90-day mortality 15:

- Preoperative pO 2 below 70 mm Hg

- Diffuse distribution and central extension of interstitial pneumonia on CT scan

- Operative blood loss

Acute interstitial pneumonitis causes

The classification system used to describe interstitial lung disease categorizes conditions based on clinical, histopathological or radiologic parameters 16. Clinical classification groups interstitial lung disease by its causes to help differentiate exogenous or endogenous factors 17. Interstitial lung disease diseases without identifiable causes get grouped under idiopathic or primary which uses the histopathological and radiological approach as its infrastructure.

Acute interstitial pneumonitis known causes 18:

- Environmental and occupational exposure: Long-term exposure to occupational or environmental agents can have a toxic effect on the lungs. Common agents are mineral dust, organic dust, and toxic gases 19. Many different types of mineral dust have correlations, but the ones frequently cited with the disease are silica, asbestos, coal mine dust, beryllium, and hard metal. Organic dust includes mold spores and aerosolized bird droppings. Inhaled toxic gases (methane, cyanide) affect the airways either by direct injury or through reactive oxygen molecules. Epidemiologically, the magnitude of exposure-related injuries is hard to measure. It probably occurs even more commonly than estimated. That is why it is invaluable to thoroughly review a patient’s entire employment history and home to look for any evidence of potential agent-disease relationships 19.

- Auto-Immune diseases: Connective tissue diseases and vasculitides affect all areas of the lungs (bronchioles, parenchyma, alveoles) which is why interstitial lung disease is a common feature of rheumatology diseases 20.

- Drug-induced interstitial lung disease: More than 350 drugs have been identified to cause pulmonary complications whether through reactive metabolites or as a component of a general response 21. A diagnosis is possible with appropriate clinical findings and in most cases should be established after excluding other causes. Radiological findings may be unpredictable, but because drug reactions usually affect the parenchyma, an interstitial pattern is what is most observed. The histopathology is also variable. The common patterns seen are eosinophilic pneumonia or hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

- Idiopathic disease: This variant is the most common type. This main category is called idiopathic interstitial pneumonia which is a combination of inflammation and fibrosis as opposed to infectious pneumonia 22. There are eight distinct types, differentiated by histopathological features with clear clinical distinctions. Most cases are sporadic, but genetics can play a role.

- Eight pathologically defined idiopathic interstitial pneumonias are included in a newly revised classification system, published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine in 2013 23:

- Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP)

- Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP)

- Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP)

- Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP)

- Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD)

- Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP)

- Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP)

- Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE)

- An additional category, “unclassifiable,” has also been added to include interstitial pneumonia not fitting a particular pathologic pattern.

- Eight pathologically defined idiopathic interstitial pneumonias are included in a newly revised classification system, published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine in 2013 23:

Many of the subsets of the disease are of unknown cause. Regardless, they all ultimately share the same manner of development. The morphological changes seen histologically result from a sequence of inflammation within the parenchyma, which is the portion of the lung involved in gas exchange (the alveoli, the alveolar ducts, and the bronchioles). This compartment is the habitat to various proteins and pro-fibrotic elements. These proteins, after repeated cycles of activation, give rise to accumulation of connective tissue 24. The trigger can be a known agent that deposited within the lung tissues. In some cases, the fibrosis arises spontaneously.

Eight pathologically defined idiopathic interstitial pneumonias are included in a newly revised classification system, published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine in 2013 23:

- Usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP)

- Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP)

- Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP)

- Desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP)

- Respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease (RB-ILD)

- Acute interstitial pneumonia (AIP)

- Lymphoid interstitial pneumonia (LIP)

- Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE)

- An additional category, “unclassifiable,” has also been added to include interstitial pneumonia not fitting a particular pathologic pattern.

Idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE), the newest pathologic subcategory, is rare and highlighted by pleural thickening predominantly in the upper lobes. It is often associated with parenchymal or interstitial findings on CT, most commonly usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP). Given the rarity of presenting cases, a confident diagnosis of idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis (PPFE) is likely best achieved by biopsy as clinical and radiologic presentation alone may be equivocal.

While interstitial pneumonias have been studied and recognized over several decades, the new classification system provides a more intuitive organization of both the prevalence and natural course of specific histologic patterns and their related clinical findings. A first approach is to separate the eight pathologically defined patterns into six major (usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP), nonspecific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), desquamative interstitial pneumonia (DIP), RB-interstitial lung disease, acute interstitial pneumonia) and two rare or less commonly encountered entities (lymphoid interstitial pneumonia [LIP] and idiopathic pleuroparenchymal fibroelastosis [PPFE]).

Of the six major patterns, a review of their courses and presentations as well as associated clinical findings further leads to three subcategorizations:

- Chronically fibrosing (usual interstitial pneumonia [UIP] and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia [NSIP])

- Smoking related (desquamative interstitial pneumonia [DIP] and respiratory bronchiolitis-interstitial lung disease [RB-ILD])

- Acutely presenting (cryptogenic organizing pneumonia [COP] and acute interstitial pneumonia)

This approach may better assist the clinician in terms of recognition and work-up of initially undifferentiated presenting disease. While any of the eight may appear independently as primary or idiopathic disease, many are involved in the progressive lung injury associated with chronic organic or inorganic exposures, drug toxicity, and autoimmune disease. A combined approach of not only characterizing the presenting clinical and radiologic features but also seeking a secondary cause is important to diagnosis and subsequent management.

Acute interstitial pneumonitis symptoms

The most frequently reported symptom of acute interstitial pneumonitis is a gradual onset of dyspnea, but sometimes it may simply be a cough. For example, in patients with bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, an unrelenting cough is usually the presenting symptom 25. Pleuritic chest pain is uncommon overall but does occur in some subtypes such as sarcoidosis. Hemoptysis may present from diffuse alveolar hemorrhages. On the other hand, a patient can be completely asymptomatic but have abnormal imaging.

The history should include details regarding potential environmental or occupational exposures, current and past medications lists, history of any radiation exposures, fumes, dust, toxic inhalation. Family history is essential as genetics can play a role. Symptoms of rheumatologic diseases should be considered, but always keep in mind that dyspnea may be the only presenting symptom for rheumatological-associated interstitial lung disease.

On physical exam, bibasilar crackles are characteristics but not necessarily a consistent finding. Patients with advanced disease may have digital clubbing or physical signs of pulmonary hypertension such as increased intensity of P2 of the second heart sound.

Acute interstitial pneumonitis diagnosis

Determining the cause and severity of interstitial lung disease can be difficult. A clinician may be able to reach a diagnosis with a detailed history and supporting laboratory but might need to involve an interprofessional team for a higher diagnostic yield 12. Interstitial lung disease deals with a diversified collection of disorders with different management approach and prognosis, which is why arriving at a final diagnosis, is paramount. It starts with a detailed patient history and physical exam coupled with laboratory testing, imaging, physiologic testing and possibly a biopsy.

Initial routine laboratory evaluation consists of complete blood count to check for evidence of hemolytic anemia for example, as can be seen in systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE or lupus), or eosinophilia, as can be seen in drug-induced. Laboratory testing should also include hepatic function, renal function, and serologic studies. In some cases may, infectious studies may be appropriate (HIV, hepatitis).

Imaging workup starts with a routine chest radiograph. The most common radiographic feature observed is a reticular pattern, however nodular or mixed patterns can be seen 26. Occasionally some of these patterns can help you narrow down the possibilities. The presence of mediastinal lymphadenopathy on an XRay might signify the presence of lymphoma or sarcoidosis. High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) can offer a better characterization of the disease and even aid in diagnosis in case of a negative CXR; the HRCT needs to be done in a supine position.

In some cases, it may show a classic radiological pattern of some disease like usual interstitial pneumonia. The classic radiological pattern of usual interstitial pneumonia on HRCT is subpleural and basilar predominant changes, reticular patterns, honeycomb changes with or without traction bronchiectasis. If the diagnosis remains unclear after combining history, laboratory results and radiological findings, invasive workup may be helpful. Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) gives nonspecific results, meaning there are no findings in a BAL that is proven pathognomonic for a particular type of interstitial lung disease. BAL, however, can be helpful when it comes to narrowing down the options. For example, in patients suspected of hypersensitivity pneumonitis, BAL will show marked lymphocytosis. The decision to pursue a lung biopsy should be individualized. Not all cases require a lung biopsy. It is most helpful in diagnosing sarcoidosis and idiopathic interstitial pneumonia.

Complete lung functions and oxymetry are necessary for all patients with interstitial lung disease for prognostication and monitoring of the disease.

Acute interstitial pneumonitis treatment

For those interstitial lung disorders with known causes, avoidance of irritant is essential. General supportive measures will include smoking cessation, pulmonary rehabilitation which can help improve functionality, and good pulmonary hygiene. Supplemental oxygen is necessary for those who demonstrate hypoxemia (SaO2 less than 88). With progressive disease despite the elimination of offending agent, corticosteroids are desirable. Patients with bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP) or hypersensitivity pneumonitis have rapid, dramatic improvement with corticosteroids. For cases that do not respond to corticosteroids, immunosuppressant therapy is an investigational therapy.

The mainstay therapy for treatment of idiopathic interstitial pneumonia is corticosteroids and immunosuppressive therapies to intercept the inflammatory process within the lungs 10. Right now, nintedanib and pirfenidone are immunosuppressant drugs that have been approved but only in the treatment of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis 11. Some studies have provided indirect evidence that early therapy within the course of the disease might correlate with therapeutic responsiveness because the lung architecture has not suffered significant derangement. Once fibrosis initiates, there has not been any treatment to reverse that process, but nintedanib can slow disease progression 12. Transplant is the sole treatment modality that can reinstate physiological function in patients.

Acute interstitial pneumonitis prognosis

Prognosis varies amongst the subgroups of interstitial lung diseases 27. Typical treatment responsive sub-classes are the following: acute eosinophilic pneumonia, cellular interstitial pneumonia, bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia (BOOP), lymphocytic interstitial pneumonitis, pulmonary capillaritis, granulomatous interstitial pneumonitis and finally, alveolar proteinosis. But in any case, prognosis still correlates with the extent of the disease on presentation. The subclasses that are notoriously resistant to therapy are advanced conditions such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

References- Raghu G, Nyberg F, Morgan G. The epidemiology of interstitial lung disease and its association with lung cancer. Br. J. Cancer. 2004 Aug;91 Suppl 2:S3-10.

- Coultas DB, Zumwalt RE, Black WC, Sobonya RE. The epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 1994 Oct;150(4):967-72.

- Disayabutr S, Calfee CS, Collard HR, Wolters PJ. Interstitial lung diseases in the hospitalized patient. BMC Med. 2015 Sep 25. 13:245.

- Feuillet S, Tazi A. Les pneumopathies infiltrantes aiguës : démarche diagnostique et approche thérapeutique [Acute interstitial pneumonia: diagnostic approach and management]. Rev Mal Respir. 2011;28(6):809-822. doi:10.1016/j.rmr.2011.01.010

- Vourlekis JS. Acute interstitial pneumonia. Clin Chest Med. 2004 Dec. 25(4):739-47, vii.

- Tabaj GC, Fernandez CF, Sabbagh E, Leslie KO. Histopathology of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias (IIP): a review. Respirology. 2015 Aug. 20 (6):873-83.

- Tomiyama N, Muller NL, Johkoh T, Cleverley JR, Ellis SJ, Akira M. Acute respiratory distress syndrome and acute interstitial pneumonia: comparison of thin-section CT findings. J Comput Assist Tomogr. 2001 Jan-Feb. 25(1):28-33.

- Ichikado K, Suga M, Müller NL, Taniguchi H, Kondoh Y, Akira M. Acute interstitial pneumonia: comparison of high-resolution computed tomography findings between survivors and nonsurvivors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002 Jun 1. 165(11):1551-6.

- Myers JL, Katzenstein AL. Beyond a consensus classification for idiopathic interstitial pneumonias: progress and controversies. Histopathology. 2009 Jan. 54(1):90-103.

- Kondoh Y, Taniguchi H, Yokoi T, Nishiyama O, Ohishi T, Kato T, Suzuki K, Suzuki R. Cyclophosphamide and low-dose prednisolone in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and fibrosing nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Eur. Respir. J. 2005 Mar;25(3):528-33.

- Cottin V, Wollin L, Fischer A, Quaresma M, Stowasser S, Harari S. Fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: knowns and unknowns. Eur Respir Rev. 2019 Mar 31;28(151).

- Jakubczyc A, Neurohr C. [Diagnosis and Treatment of Interstitial Lung Diseases]. Dtsch. Med. Wochenschr. 2018 Dec;143(24):1774-1777.

- Olson J, Colby TV, Elliott CG. Hamman-Rich syndrome revisited. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990 Dec. 65(12):1538-48.

- Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, King TE Jr, Lynch DA, Nicholson AG. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013 Sep 15. 188(6):733-48.

- Fukui M, Suzuki K, Oh S, et al. Distribution of interstitial pneumonia: a new radiological predictor of 90-day mortality after resection of lung cancer. Surg Today. 2016 Jan. 46 (1):66-73.

- Rivera-Ortega P, Molina-Molina M. Interstitial Lung Diseases in Developing Countries. Ann Glob Health. 2019 Jan 22;85(1).

- Mikolasch TA, Garthwaite HS, Porter JC. Update in diagnosis and management of interstitial lung disease . Clin Med (Lond). 2017 Apr;17(2):146-153.

- Antoine M, Mlika M. Interstitial Lung Disease. [Updated 2020 Aug 15]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541084

- Luckhardt TR, Müller-Quernheim J, Thannickal VJ. Update in diffuse parenchymal lung disease 2011. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2012 Jul 01;186(1):24-9.

- Mira-Avendano I, Abril A, Burger CD, Dellaripa PF, Fischer A, Gotway MB, Lee AS, Lee JS, Matteson EL, Yi ES, Ryu JH. Interstitial Lung Disease and Other Pulmonary Manifestations in Connective Tissue Diseases. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2019 Feb;94(2):309-325.

- Skeoch S, Weatherley N, Swift AJ, Oldroyd A, Johns C, Hayton C, Giollo A, Wild JM, Waterton JC, Buch M, Linton K, Bruce IN, Leonard C, Bianchi S, Chaudhuri N. Drug-Induced Interstitial Lung Disease: A Systematic Review. J Clin Med. 2018 Oct 15;7(10).

- Capron F. [New classification of interstitial lung disease]. Rev Pneumol Clin. 2005 Jun;61(3):133-40.

- Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2013;188(6):733-748. doi:10.1164/rccm.201308-1483ST https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5803655

- Suki B, Stamenović D, Hubmayr R. Lung parenchymal mechanics. Compr Physiol. 2011 Jul;1(3):1317-51.

- Ryu JH, Olson EJ, Midthun DE, Swensen SJ. Diagnostic approach to the patient with diffuse lung disease. Mayo Clin. Proc. 2002 Nov;77(11):1221-7; quiz 1227.

- Raghu G, Brown KK. Interstitial lung disease: clinical evaluation and keys to an accurate diagnosis. Clin. Chest Med. 2004 Sep;25(3):409-19, v.

- Kolb M, Vašáková M. The natural history of progressive fibrosing interstitial lung diseases. Respir. Res. 2019 Mar 14;20(1):57.