Acute retroviral syndrome also called acute human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) syndrome, is the first stage of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Acute retroviral syndrome symptoms are similar to the flu such as headache, nausea, diarrhea, and body aches and disappear on their own within weeks and are often mistaken for those of another viral infection (see differential diagnosis of acute HIV infection below). Patients with the acute retroviral syndrome may have fever, fatigue, rash, pharyngitis or other symptoms 1. During this period, you are very infectious. More-persistent or more-severe symptoms of HIV infection may not appear for several years after the initial infection. Even though symptoms of acute retroviral syndrome may disappear, a person is still infected with HIV and can spread the infection. Although there currently is no cure for HIV infection, a combination of medicines called antiretroviral therapy (ART) can help people with HIV stay healthy and live an active life. These types of medications work against the HIV, controlling the growth and reducing chances of transmission. ART combined with other medicines known as an HIV regimen help control symptoms, slow growth, decrease transmission probability with the overall goal of the person living a longer, healthier life. The caveat to this treatment is the person will always be HIV positive, and the service is expensive.

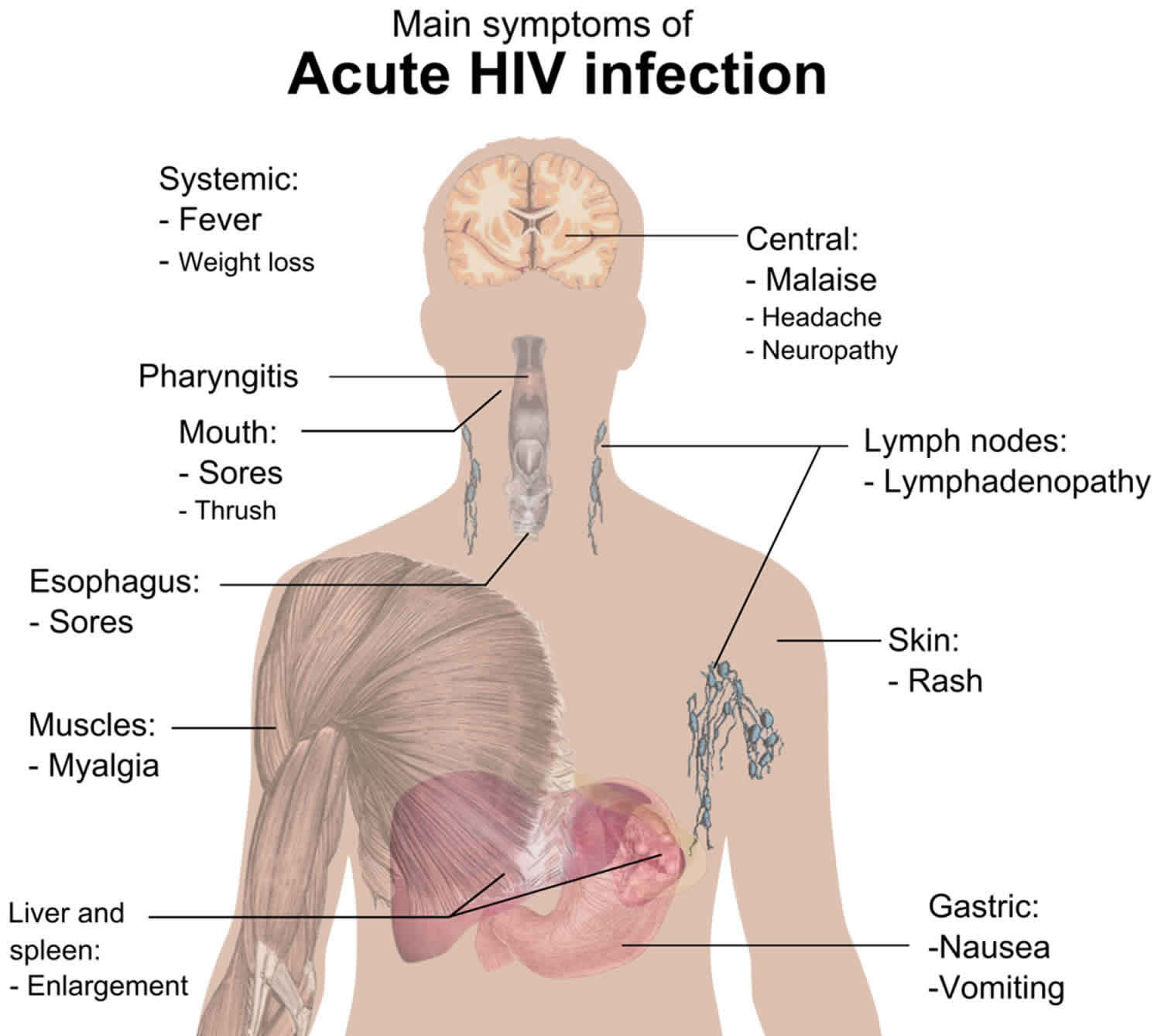

Acute retroviral syndrome or primary HIV infection symptoms usually occur within a couple of weeks to a month or two after infection and are often like a bad case of the flu. In many people, early HIV signs and symptoms include:

- Fever

- Headache

- Fatigue

- Swollen lymph glands (lymphadenopathy)

- Rash

- Sore joints (arthralgia) or muscle aches (myalgia)

- Sore throat

Longer duration and greater severity of acute retroviral syndrome have been associated with more rapid progression of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection and worse clinical outcomes 2. It has been postulated that individuals presenting with more severe acute retroviral syndrome may receive enhanced benefit from antiretroviral therapy (ART) initiation during acute human immunodeficiency virus infection 3. Early recognition of acute retroviral syndrome and initiation of ART can potentially halt onward transmission of HIV during a period of exceptional infectivity 4, limit establishment of HIV reservoirs 5 and improve immune reconstitution 6.

The differential diagnosis of the early findings of acute HIV infection can be confusing. Because of a low index of suspicion, the diagnosis is missed in as many as 75 percent of patients 7. Acute HIV infection may resemble infectious mononucleosis, influenza, severe streptococcal pharyngitis, viral hepatitis, toxoplasmosis or even secondary syphilis (see differential diagnosis of acute HIV infection below). For example, a patient with symptoms suggestive of HIV infection could actually be an HIV-negative young adult manifesting for the first time the effects of a primary immunodeficiency disease involving B-cell and/or T-cell dysfunction. Immunoglobulin A deficiency—by far the most common immunodeficient condition—often presents after the age of 21 years 8. On the other hand, a patient who returns from the tropics with an unexplained febrile illness is frequently assumed to have malaria, typhoid, schistosomiasis, filariasis or an intestinal helminthic infection but may actually have HIV infection. One study found that 3 percent of such travelers were infected with HIV 9. In areas where AIDS and malaria are endemic, 23 percent of fevers are ultimately attributable to HIV infection and only 15 percent to malaria 10. Age is also a factor, with the diagnosis of acute HIV infection often delayed in patients over 50 years old 11.

Differential diagnosis of acute HIV infection:

- Primary cytomegalovirus infection

- Drug reaction

- Epstein-Barr virus mononucleosis

- Viral hepatitis

- Primary herpes simplex virus infection

- Influenza

- Severe (streptococcal) pharyngitis

- Secondary syphilis

- Toxoplasmosis

- Rubella

- Brucellosis

- Malaria

Figure 1. Acute retroviral syndrome rash

Acute retroviral syndrome symptoms usually develop within days to weeks after HIV exposure and last from a few days to several months, but usually less than 14 days 7.

It is estimated that acute HIV infection syndrome occurs in 40 to 90% of people infected with HIV during the first few weeks after initial exposure 12.

HIV infection occurs predominately through sexual exposure in most areas of the world. There are some geographical areas where intravenous transmission among intravenous drug users or via nosocomial transmission also occur. Mother to child transmission is becoming less frequent as a result of HIV testing and treatment during pregnancy.

How does HIV spread?

To become infected with HIV, infected blood, semen or vaginal secretions must enter your body. This can happen in several ways:

- By having sex. You may become infected if you have vaginal, anal or oral sex with an infected partner whose blood, semen or vaginal secretions enter your body. The virus can enter your body through mouth sores or small tears that sometimes develop in the rectum or vagina during sexual activity.

- By sharing needles. Sharing contaminated IV drug paraphernalia (needles and syringes) puts you at high risk of HIV and other infectious diseases, such as hepatitis.

- From blood transfusions. In some cases, the virus may be transmitted through blood transfusions. American hospitals and blood banks now screen the blood supply for HIV antibodies, so this risk is very small.

- During pregnancy or delivery or through breast-feeding. Infected mothers can pass the virus on to their babies. Mothers who are HIV-positive and get treatment for the infection during pregnancy can significantly lower the risk to their babies.

Anyone of any age, race, sex or sexual orientation can be infected with HIV/AIDS. However, you’re at greatest risk of HIV/AIDS if you:

- Have unprotected sex. Use a new latex or polyurethane condom every time you have sex. Anal sex is more risky than is vaginal sex. Your risk of HIV increases if you have multiple sexual partners.

- Have an sexually transmitted infection (STI). Many STIs produce open sores on your genitals. These sores act as doorways for HIV to enter your body.

- Use IV drugs. People who use IV drugs often share needles and syringes. This exposes them to droplets of other people’s blood.

How HIV doesn’t spread?

You can’t become infected with HIV through ordinary contact. That means you can’t catch HIV or AIDS by hugging, kissing, dancing or shaking hands with someone who has the infection.

HIV isn’t spread through the air, water or insect bites.

The symptoms of acute HIV infection syndrome settle within a few days to weeks.

Once HIV infection is established, there is a clinical latency period when patients may be asymptomatic. The median time of this period is approximately 10 years, during which there is active HIV replication and CD4 T-cell count declines.

Chronic HIV symptoms are variable, mostly depending on CD4 count and/or viral load. If HIV infection is not detected and treated with ART, progression to AIDS spectrum of illness is inevitable with opportunistic infections and/or malignancy.

How does HIV become AIDS?

HIV destroys CD4 T cells — white blood cells that play a large role in helping your body fight disease. The fewer CD4 T cells you have, the weaker your immune system becomes.

You can have an HIV infection, with few or no symptoms, for years before it turns into AIDS. AIDS is diagnosed when the CD4 T cell count falls below 200 or you have an AIDS-defining complication, such as a serious infection or cancer.

HIV belongs to the Retroviridae family of viruses. There are two subgroups: HIV-1 and HIV 2.

- HIV-1 infection causes most cases worldwide

- HIV-2 infection cases are infrequent with nearly all cases arising in West Africa

Symptoms begin after the HIV virus has successfully infected its specific target, T helper/CD4 cells, followed by bursting viremia 13. A very high viral load incites cytokine production by the innate immune system causing the acute retroviral syndrome 14.

The most common findings of the acute retroviral syndrome are fever (80 to 90 percent), fatigue (70 to 90 percent), rash (40 to 80 percent), headache (32 to 70 percent) and lymphadenopathy (40 to 70 percent). Additional findings include pharyngitis, myalgia, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea and other symptoms (Table 1) 15. Acute retroviral syndrome is typically described as a mononucleosis-like illness with prevalence estimates varying widely, depending on the population studied, from 23% to 92% of newly infected individuals 16.

The symptoms that indicate an early HIV infection are extremely common. Often, you can’t tell them apart from symptoms of another viral infection. If you’re concerned that you might have been exposed to HIV, talk to your doctor about your testing options.

Table 1. Frequency of symptoms and findings associated with acute retroviral syndrome or acute HIV infection

| Symptoms or findings | Percentage of patients |

|---|---|

| Fever | >80 to 90 |

| Fatigue | >70 to 90 |

| Rash | >40 to 80 |

| Headache | 32 to 70 |

| Lymphadenopathy | 40 to 70 |

| Pharyngitis | 50 to 70 |

| Myalgia or arthralgia | 50 to 70 |

| Nausea, vomiting or diarrhea | 30 to 60 |

| Night sweats | 50 |

| Aseptic meningitis | 24 |

| Oral ulcers | 10 to 20 |

| Genital ulcers | 5 to 15 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 45 |

| Leukopenia | 40 |

| Elevated hepatic enzyme levels | 21 |

HIV can be diagnosed through blood or saliva testing. Available tests include:

- Antigen/antibody tests. These tests usually involve drawing blood from a vein. Antigens are substances on the HIV virus itself and are usually detectable — a positive test — in the blood within a few weeks after exposure to HIV. Antibodies are produced by your immune system when it’s exposed to HIV. It can take weeks to months for antibodies to become detectable. The combination antigen/antibody tests can take two to six weeks after exposure to become positive.

- Antibody tests. These tests look for antibodies to HIV in blood or saliva. Most rapid HIV tests, including self-tests done at home, are antibody tests. Antibody tests can take three to 12 weeks after you’re exposed to become positive.

- Nucleic acid tests (NATs). These tests look for the actual virus in your blood (viral load). They also involve blood drawn from a vein. If you might have been exposed to HIV within the past few weeks, your doctor may recommend NAT. NAT will be the first test to become positive after exposure to HIV.

Talk to your doctor about which HIV test is right for you. If any of these tests are negative, you may still need a follow-up test weeks to months later to confirm the results.

Blood taken during the acute phase of HIV infection (days to weeks after exposure) may show lymphopenia and thrombocytopenia, but atypical lymphocytes are infrequent. The CD4 count usually remains normal. The HIV-1 antibody tests (ELISA and Western blot test), the only tests officially used to diagnose established HIV infection, do not become positive until three or four weeks (sometimes even months) after the infection is acquired 17.

On the other hand, the quantitative plasma HIV-1 RNA level (viral load) by polymerase chain reaction (PCR), which is 95 to 98 percent sensitive for HIV 18, becomes positive within 11 days of infection 19. During the symptomatic phase of acute HIV infection, the viral RNA shows in excess of 50,000 copies per mL 7. Three instances of false-positive HIV-1-RNA tests have been reported; in each instance, however, the person was not having symptoms, and the viral load was less than 2,000 copies per mL 20. The presence of high-titer HIV-I RNA (more than 50,000 copies per mL) in the absence of HIV antibodies establishes the diagnosis of acute HIV infection 7.

HIV-1 antibody and viral load tests are readily available through commercial laboratories and should be performed whenever a patient presents with signs and symptoms of acute retroviral syndrome or acute HIV syndrome and a history that is compatible with HIV infection. If viral RNA quantitation is not available, a serum or plasma p24 antigen test may be used to detect viral infection before the appearance of HIV antibodies.

If acute HIV infection is strongly suspected but the HIV-1 RNA PCR test is negative or shows a low titer, the initial high level of viral RNA may have already subsided. The patient should be followed with HIV-1 antibody tests at three months, six months and one year. If these tests remain negative, another diagnosis should be considered.

Tests to stage disease and treatment

If you’ve been diagnosed with HIV, it’s important to find a specialist trained in diagnosing and treating HIV to help you:

- Determine whether you need additional testing

- Determine which HIV antiretroviral therapy (ART) will be best for you

- Monitor your progress and work with you to manage your health

If you receive a diagnosis of HIV/AIDS, several tests can help your doctor determine the stage of your disease and the best treatment, including:

- CD4 T cell count. CD4 T cells are white blood cells that are specifically targeted and destroyed by HIV. Even if you have no symptoms, HIV infection progresses to AIDS when your CD4 T cell count dips below 200.

- Viral load (HIV RNA). This test measures the amount of virus in your blood. After starting HIV treatment the goal is to have an undetectable viral load. This significantly reduces your chances of opportunistic infection and other HIV-related complications.

- Drug resistance. Some strains of HIV are resistant to medications. This test helps your doctor determine if your specific form of the virus has resistance and guides treatment decisions.

Tests for complications

Your doctor might also order lab tests to check for other infections or complications, including:

- Tuberculosis

- Hepatitis B or hepatitis C virus infection

- Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)

- Liver or kidney damage

- Urinary tract infection

- Cervical and anal cancer

- Cytomegalovirus

- Toxoplasmosis

Currently, there’s no cure for HIV/AIDS. Once you have the infection, your body can’t get rid of it. However, there are many medications that can control HIV and prevent complications. These medications are called antiretroviral therapy (ART). Everyone diagnosed with HIV should be started on ART, regardless of their stage of infection or complications. Compelling reports indicate that the administration of potent antiretroviral therapy (ART) can result in a rapid and sustained decline in the viral load to below the limit of detection within three months 21. Furthermore, studies of CD4 and CD8 lymphocyte dynamics show restoration of the normal ratio, reflecting recovery of the immune system 22. In one investigation of HIV-1–specific cell-mediated immune responsiveness, treatment of acute HIV infection resulted in the restoration of virus-specific immunity with control of viremia in six of six persons studied 23.

ART is usually a combination of three or more medications from several different drug classes. This approach has the best chance of lowering the amount of HIV in the blood. There are many ART options that combine three HIV medications into one pill, taken once daily.

Each class of drugs blocks the virus in different ways. Treatment involves combinations of drugs from different classes to:

- Account for individual drug resistance (viral genotype)

- Avoid creating new drug-resistant strains of HIV

- Maximize suppression of virus in the blood

Two drugs from one class, plus a third drug from a second class, are typically used.

The classes of anti-HIV drugs include:

- Non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NNRTIs) turn off a protein needed by HIV to make copies of itself. Examples include efavirenz (Sustiva), rilpivirine (Edurant) and doravirine (Pifeltro).

- Nucleoside or nucleotide reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) are faulty versions of the building blocks that HIV needs to make copies of itself. Examples include abacavir (Ziagen), tenofovir (Viread), emtricitabine (Emtriva), lamivudine (Epivir) and zidovudine (Retrovir). Combination drugs also are available, such as emtricitabine/tenofovir (Truvada) and emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide (Descovy).

- Protease inhibitors inactivate HIV protease, another protein that HIV needs to make copies of itself. Examples include atazanavir (Reyataz), darunavir (Prezista) and lopinavir/ritonavir (Kaletra).

- Integrase inhibitors work by disabling a protein called integrase, which HIV uses to insert its genetic material into CD4 T cells. Examples include bictegravir sodium/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide fumar (Biktarvy), raltegravir (Isentress) and dolutegravir (Tivicay).

- Entry or fusion inhibitors block HIV’s entry into CD4 T cells. Examples include enfuvirtide (Fuzeon) and maraviroc (Selzentry).

Starting and maintaining treatment

Everyone with HIV infection, regardless of the CD4 T cell count or symptoms, should be offered antiviral medication.

Remaining on effective ART with an undetectable HIV viral load in the blood is the best way for you to stay healthy.

For ART to be effective, it’s important that you take the medications as prescribed, without missing or skipping any doses. Staying on ART with an undetectable viral load helps:

- Keep your immune system strong

- Reduce your chances of getting an infection

- Reduce your chances of developing treatment-resistant HIV

- Reduce your chances of transmitting HIV to other people

Staying on HIV therapy can be challenging. It’s important to talk to your doctor about possible side effects, difficulty taking medications, and any mental health or substance use issues that may make it difficult for you to maintain ART.

Having regular follow-up appointments with your doctor to monitor your health and response to treatment is also important. Let your doctor know right away if you’re having problems with HIV therapy so that you can work together to find ways to address those challenges.

Treatment side effects

Treatment side effects can include:

- Nausea, vomiting or diarrhea

- Heart disease

- Kidney and liver damage

- Weakened bones or bone loss

- Abnormal cholesterol levels

- Higher blood sugar

- Cognitive and emotional problems, as well as sleep problems

Treatment response

Early institution of antiretroviral therapy has the advantage of keeping the viral load low by reducing replication and the appearance of resistant HIV phenotypes. It also may prevent immune depletion because of increased immune stimulation resulting from the strong antigenicity of HIV during primary infection 24. This allows for a more favorable initial immune response to HIV.

Your doctor will monitor your viral load and CD4 T cell counts to determine your response to HIV treatment. These will be initially checked at two and four weeks, and then every three to six months.

Treatment should lower your viral load so that it’s undetectable in the blood. That doesn’t mean your HIV is gone. Even if it can’t be found in the blood, HIV is still present in other places in your body, such as in lymph nodes and internal organs.

If acute HIV infection is not treated, the signs and symptoms disappear, along with the viremia. The person enters a prolonged stage of hidden viral replication during which the virus may not be culturable from the blood and HIV-1 RNA levels may be low or undetectable. During the next five to 10 years, lymph node architecture is destroyed, certain CD4 and CD8 cell lines are gradually depleted and progression to symptomatic disease ultimately occurs 25. Some subtle effects develop, reflecting early encephalopathy 26, but the liver, kidneys and lipid metabolism are spared.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Along with receiving medical treatment, it’s essential to take an active role in your own care. The following suggestions may help you stay healthy longer:

- Eat healthy foods. Make sure you get enough nourishment. Fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, and lean protein help keep you strong, give you more energy and support your immune system.

- Avoid raw meat, eggs and more. Foodborne illnesses can be especially severe in people who are infected with HIV. Cook meat until it’s well done. Avoid unpasteurized dairy products, raw eggs and raw seafood such as oysters, sushi or sashimi.

- Get the right vaccinations. These may prevent typical infections such as pneumonia and influenza. Your doctor may also recommend other vaccinations, including for HPV, hepatitis A and hepatitis B. Inactivated vaccines are generally safe, but most vaccines with live viruses are not, due to your weakened immune system.

- Take care with companion animals. Some animals may carry parasites that can cause infections in people who are HIV-positive. Cat feces can cause toxoplasmosis, reptiles can carry salmonella, and birds can carry cryptococcus or histoplasmosis. Wash hands thoroughly after handling pets or emptying the litter box.

Alternative medicine

People who are infected with HIV sometimes try dietary supplements that claim to boost the immune system or counteract side effects of anti-HIV drugs. However, there is no scientific evidence that any nutritional supplement improves immunity, and many may interfere with other medications you’re taking. Always check with your doctor before taking any supplements or alternative therapies to ensure there are no medication interactions.

Supplements that may be helpful:

- Acetyl-L-carnitine. Researchers have used acetyl-L-carnitine to treat nerve pain, numbness or weakness (neuropathy) in people with diabetes. It may also ease neuropathy linked to HIV if you’re lacking in the substance.

- Whey protein and certain amino acids. Early evidence suggests that whey protein, a cheese byproduct, can help some people with HIV gain weight. Whey protein also appears to reduce diarrhea and increase CD4 T cell counts. The amino acids L-glutamine, L-arginine and hydroxymethylbutyrate (HMB) may also help with weight gain.

- Probiotics. There is some evidence that the probiotic Saccharomyces boulardii may help with HIV-related diarrhea, but use only as directed by your doctor. Bovine colostrum is also being studied for treating diarrhea.

- Vitamins and minerals. Vitamins A, D, E, C and B — as well as the minerals zinc, iron and selenium — may be helpful if you have low levels of them.

Supplements that may be dangerous:

- St. John’s wort. A common depression remedy, St. John’s wort can reduce the effectiveness of several types of anti-HIV drugs by more than half.

- Garlic supplements. Although garlic itself may help strengthen the immune system, garlic supplements may interact with some anti-HIV drugs and reduce their ability to work. Occasionally eating garlic in food appears to be safe.

- Red yeast rice extract. Some people use this to lower cholesterol, but avoid it if you take a protease inhibitor or a statin.

Mind-body practices

Practices such as yoga, meditation and tai chi have been shown to reduce stress, as well as improve blood pressure and quality of life. While they need more study, these practices may be helpful if you’re living with HIV/AIDS.

Coping and support

Receiving a diagnosis of any life-threatening illness is devastating. The emotional, social and financial consequences of HIV/AIDS can make coping with this illness especially difficult — not only for you but also for those closest to you.

But today, there are many services and resources available to people with HIV. Most HIV/AIDS clinics have social workers, counselors or nurses who can help you directly or put you in touch with people who can.

Services they may provide:

- Arrange transportation to and from doctor appointments

- Help with housing and child care

- Assist with employment and legal issues

- Provide support during financial emergencies

It’s important to have a support system. Many people with HIV/AIDS find that talking to someone who understands their disease provides comfort.

References- Perlmutter BL, Glaser JB, Oyugi SO. How to recognize and treat acute HIV syndrome [published correction appears in Am Fam Physician 2000 Jan 15;61(2):308]. Am Fam Physician. 1999;60(2):535-546. https://www.aafp.org/afp/1999/0801/p535.html

- Lavreys L, Baeten JM, Chohan Vet al. Higher set point plasma viral load and more-severe acute HIV type 1 (HIV-1) illness predict mortality among high-risk HIV-1-infected African women. Clin Infect Dis2006; 42:1333–9.

- Braun DL, Kouyos R, Oberle Cet al. A novel acute retroviral syndrome severity score predicts the key surrogate markers for HIV-1 disease progression. PLoS One2014; 9:e114111.

- Brenner BG, Roger M, Routy JPet al. Quebec Primary HIV Infection Study Group. High rates of forward transmission events after acute/early HIV-1 infection. J Infect Dis2007; 195:951–9.

- Crowell TA, Fletcher JL, Sereti Iet al. RV254/SEARCH010 Study Group. Initiation of antiretroviral therapy before detection of colonic infiltration by HIV reduces viral reservoirs, inflammation and immune activation. J Int AIDS Soc2016; 19:21163

- Hocqueloux L, Avettand-Fènoël V, Jacquot Set al. AC32 (Coordinated Action on HIV Reservoirs) of the Agence Nationale de Recherches sur le Sida et les Hépatites Virales (ANRS). Long-term antiretroviral therapy initiated during primary HIV-1 infection is key to achieving both low HIV reservoirs and normal T cell counts. J Antimicrob Chemother2013; 68:1169–78.

- Kahn JO, Walker BD. Acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:33–9.

- Stadtmauer G, Cunningham-Rundles C. Primary immune disorders that mimic AIDS. Infect Med. 1997;14:899–905.

- Doherty JF, Grant AD, Byceson AD. Fever as the presenting complaint of travellers returning from the tropics. QJM. 1995;88:277–81.

- Nwanyanwu OC, Kumwenda N, Kazembe PN, Jemu S, Ziba C, Nkhoma WC, et al. Malaria and human immunodeficiency virus infection among male employees of a sugar estate in Malawi. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:567–9.

- AIDS among persons aged > or = 50 years—United States, 1991–1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1998;47:21–7.

- Schacker T, et al. Clinical and epidemiologic features of primary HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 1996; 125 (4): 257-64. (Cited by: Chu C, Selwyn PA. Diagnosis and initial management of acute HIV infection. Am Fam Physician. 2010; 81 (10): 1239-44.

- Fauci AS, Lane HC. Human immunodeficiency virus disease: AIDS and related disorders. In: Longo DL, Fauci AS, Kasper DL, Hauser SL, Jameson JL, Localzo J. Harrison’s principles of internal medicine. 18th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. p. 1506-87.

- Stacey AR, Norris PJ, Qin L, et al. Induction of striking systemic cytokine cascade prior to peak viremia in acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection, in contrast to more modest and delayed responses in acute hepatitis B and C virus infection. J Virol. 2009; 83 (8): 3719-33. (Cited by: Cohen MS, Gay CL, Busch MP, Hecht FM. The detection of acute HIV infection. JID. 2010; 202: s270-7.

- Vanhems P, Allard R, Cooper DA, Perrin L, Vizzard J, Hirschel B, et al. Acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 disease as a mononucleosis-like illness: is the diagnosis too restrictive? Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:965–70 [Published erratum in Clin Infect Dis. 1997;25:325].

- Braun DL, Kouyos RD, Balmer B, Grube C, Weber R, Günthard HF. Frequency and spectrum of unexpected clinical manifestations of primary HIV-1 infection. Clin Infect Dis2015; 61:1013–21.

- Trevor A Crowell, Donn J Colby, Suteeraporn Pinyakorn, James L K Fletcher, Eugène Kroon, Alexandra Schuetz, Shelly J Krebs, Bonnie M Slike, Louise Leyre, Nicolas Chomont, Linda L Jagodzinski, Irini Sereti, Netanya S Utay, Robin Dewar, Rungsun Rerknimitr, Nitiya Chomchey, Rapee Trichavaroj, Victor G Valcour, Serena Spudich, Nelson L Michael, Merlin L Robb, Nittaya Phanuphak, Jintanat Ananworanich, RV254/SEARCH010 Study Group, Acute Retroviral Syndrome Is Associated With High Viral Burden, CD4 Depletion, and Immune Activation in Systemic and Tissue Compartments, Clinical Infectious Diseases, Volume 66, Issue 10, 15 May 2018, Pages 1540–1549, https://doi.org/10.1093/cid/cix1063

- Dailey P, Hayden D. Viral load assays: methodologies, variables, and interpretation. In: Cohen PT, Sande MA, Volberding PA, eds. The AIDS knowledge base: a textbook on HIV disease from the University of California, San Francisco, and San Francisco General Hospital. 3d ed. San Francisco: HIV InSite, 1998.

- Busch MP, Lee LL, Satten GA, Henrad DR, Farzadegan H, Nelson KE, et al. Time course of detection of viral and serologic markers preceding human immunodeficiency virus type 1 seroconversion: implications for screening of blood and tissue donors. Transfusion. 1995;35:91–7.

- Rich JD, Merriman NA, Mylonakis E, Greenough TC, Flanigan TP, Mady BJ, et al. Misdiagnosis of HIV infection by HIV-1 plasma viral load testing: a case series. Ann Intern Med. 1999;130:37–9.

- Lafeuillade A, Poggi C, Chollet L, et al. Long-term evaluation of triple therapy administered since primary HIV-1 infection (PHI) [Abstract]. In: Proceedings of the 12th World AIDS Conference; 1998 Jun 28–Jul 3, Geneva, Switzerland. Bologna: Monduzzi, 1998.

- Kinloch-De Loes S, Tilling RS, Turnbull W, et al. Naive T cell subsets during acute infection (AI) with HIV and response to highly active antiretroviral infection [Abstract]. In: Proceedings of the 12th World AIDS Conference; 1998 Jun 28–Jul 3, Geneva, Switzerland. Bologna: Monduzzi, 1998.

- Walker BD. HIV infection: the body fights back [Abstract]. In: Program and abstracts of the 5th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections; 1998 Feb 1–5; Chicago. Alexandria. Va.: Foundation for Retrovirology and Human Health, 1998.

- Rosenberg ES, Billingsley JM, Caliendo AM, Boswell SL, Sax PE, Kalams SA, et al. Vigorous HIV-1-specific CD4+ T cell responses ass ociated with control of viremia. Science. 1997;278:1447–50.

- Fauci AS, Pantaleo G, Stanley S, Weissman D. Immunopathogenic mechanisms of HIV infection. Ann Intern Med. 1996;124:654–63.

- Clifford D. Primary neurologic complications of HIV infection. International AIDS Society—USA 1998;5:4–7.