Atrioventricular canal defect

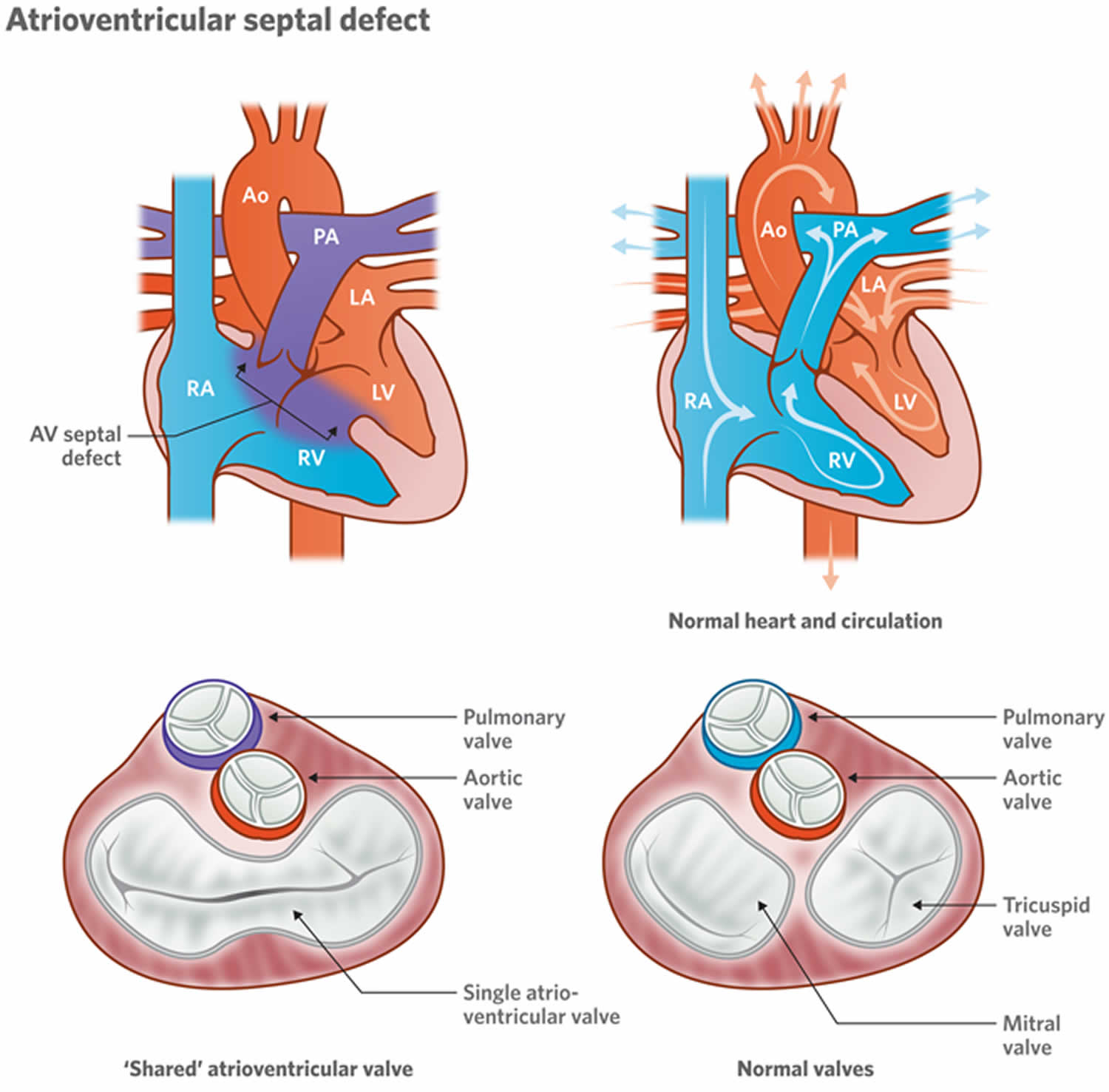

Atrioventricular canal defect also called atrioventricular septal defect or endocardial cushion defect means there is a large hole in the septum or the wall that separates the right and left sides of the heart. Atrioventricular canal defect occurs when there’s a hole between the heart’s chambers and problems with the valves that regulate blood flow in the heart. A atrioventricular canal defect may be classified as partial or complete. In a partial canal defect, either the upper (atrial) or lower (ventricular) part of the septum may be affected. A complete canal defect, which is more common, means that the hole is located where the upper (atrial) and lower (ventricular) parts of the septum meet.

Normally, the tricuspid valve directs blood from the upper-right chamber (the right atrium) to the lower-right chamber (the right ventricle), and the mitral valve allows blood to move from the upper-left chamber (the left atrium) to the lower-left chamber (the left ventricle). But with complete AV canal defect, just one large hole and one valve are present, and the valve may not close all the way. This allows blood to flow in all directions inside the heart.

Atrioventricular canal defect:

- A hole in the wall dividing the heart’s upper chambers (atrial septal defect or ASD),

- A hole in the wall separating the heart’s lower chambers (ventricular septal defect or VSD) and

- Abnormalities of the tricuspid and mitral valves.

Some patients with AV canal defects have a small or no opening between the bottom chambers of the heart. They can present in adulthood with findings similar to patients with atrial septal defects; this can be referred to as an “ostium primum” atrial septal defect. Even less commonly, only the hole between the lower chambers is present.

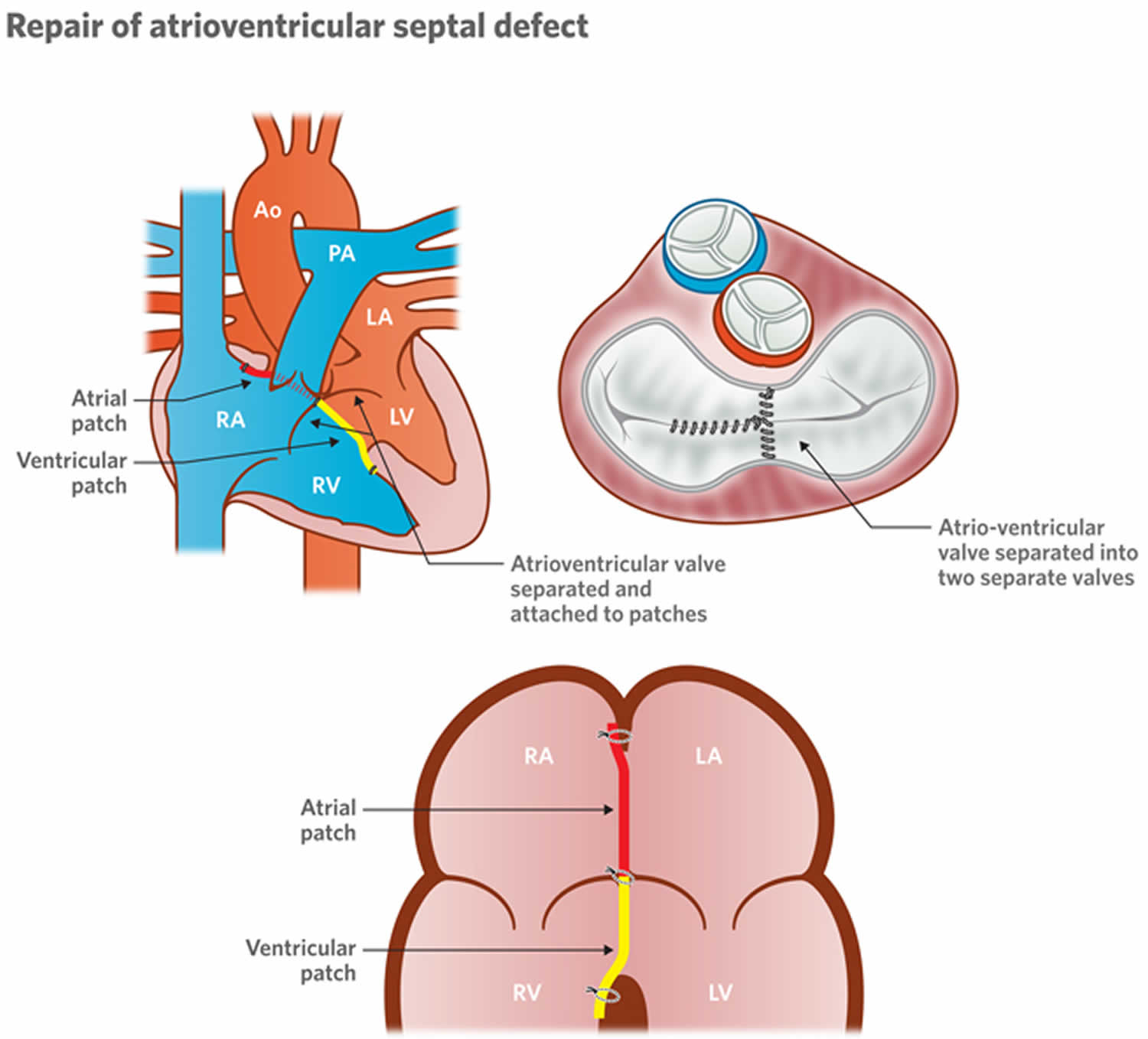

Surgery is needed to repair complete and partial atrioventricular canal defects. Surgery is usually done in the first few months after birth (most cases in the first four to six months) to correct a complete AV canal defect.

The procedure involves closing the hole in the wall (septum) between the heart chambers with one or two patches. The patches stay in the heart permanently, becoming part of the septum as the heart’s lining grows over them.

For a partial atrioventricular canal defect, surgery also involves repair of the mitral valve, so it will close tightly. If repair isn’t possible, the valve might need to be replaced.

For a complete atrioventricular canal defect, surgery also includes separation of the large single valve that separates the upper and lower chambers of the heart into two valves, on both the left and right sides of the repaired septum. If separating the single valve isn’t possible, heart valve replacement of both the tricuspid and mitral valves might be needed.

Normal heart

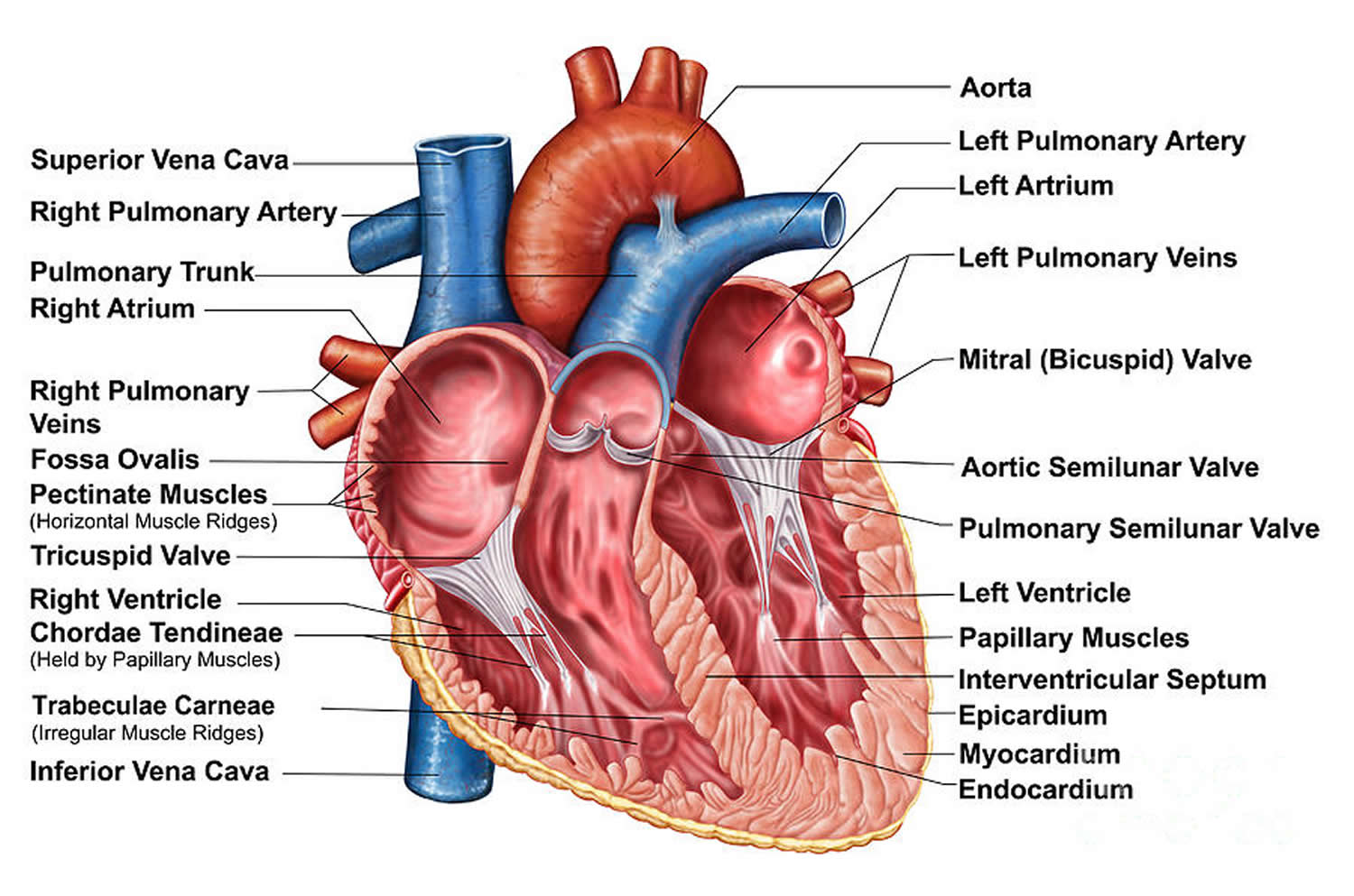

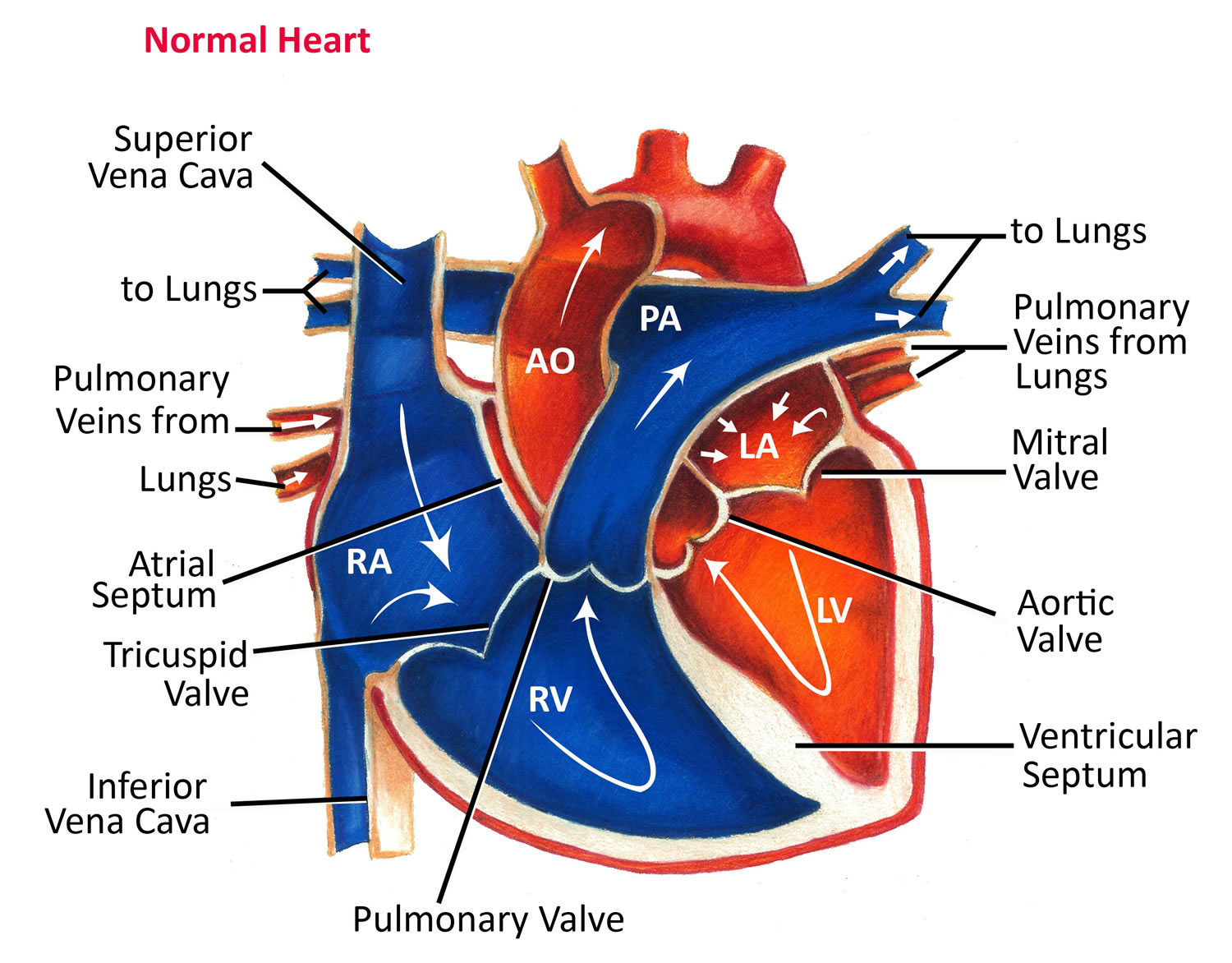

The heart is divided into four chambers, two on the right and two on the left.

The right side of your heart moves blood into vessels that lead to the lungs. There, oxygen enriches the blood. The oxygen-rich blood flows back to your heart’s left side and is pumped into a large vessel (aorta) that circulates blood to the rest of your body.

Valves control the flow of blood into and out of the chambers of your heart. These valves open to allow blood to move to the next chamber or to one of the arteries, and close to keep blood from flowing backward.

Figure 1. The anatomy of the heart chambers

Figure 2. Normal heart blood flow

Figure 3. Atrioventricular canal defect

Partial atrioventricular canal defect

In partial atrioventricular canal defect:

- There’s a hole in the wall (septum) that separates the upper chambers (atria) of the heart.

- Often the valve between the upper and lower left chambers (mitral valve) also has a defect that causes it to leak (mitral valve regurgitation).

Complete AV canal defect

In complete atrioventricular canal defect:

- There’s a large hole in the center of the heart where the walls between the atria and the lower chambers (ventricles) meet. Oxygen-rich and oxygen-poor blood mix through that hole.

- Instead of separate valves on the right and left, there’s one large valve between the upper and lower chambers.

- The abnormal valve leaks blood into the ventricles.

- The heart is forced to work harder and enlarges.

Complete atrioventricular canal defect allows blood to mix and the chambers and valves to not properly route the blood to each station of circulation. Atrioventricular (AV) canal defect is a large hole in the center of the heart. It’s located where the wall (septum) between the upper chambers (atria) joins the wall between the lower chambers (ventricles). This septal defect involves both upper and lower chambers. Also, the tricuspid and mitral valves that normally separate the heart’s upper and lower chambers aren’t formed as individual valves. Instead, a single large valve forms that crosses the defect in the wall between the two sides of the heart. Sometimes there’s leakiness (regurgitation) of the abnormal single valve. This may add to the heart failure symptoms.

Normally, the left side of the heart only pumps blood to the body, and the heart’s right side only pumps blood to the lungs. In a child with AV canal defect, blood can travel across the holes from the left heart chambers to the right heart chambers and out into the lung arteries. The extra blood being pumped into the lung arteries makes the heart and lungs work harder and the lungs can become congested.

High pressure may occur in the blood vessels in the lungs that can lead to permanent damage with pulmonary hypertension that persists into adulthood.

Many adults who have not had previous repair have pulmonary hypertension (see Eisenmenger’s syndrome). This complication is more common than in patients with an atrial septal defect or a ventricular septal defect. Even in adults without Eisenmenger’s syndrome, symptoms including shortness of breath, intolerance to exercise and palpitations are common. On physical examinations, murmurs due to the blood flow across the defects and due to the valve leak are common.

AV canal defect causes

Atrioventricular canal defect occurs before birth when a baby’s heart is developing. In most children, the cause of atrioventricular canal defect isn’t known. It’s a very common type of heart defect in children with a chromosome problem, Trisomy 21 (Down syndrome). Some children can have other heart defects along with AV canal.

Risk factors for AV canal defect

Factors that might increase a baby’s risk of developing atrioventricular canal defect before birth include:

- Down syndrome

- German measles (rubella) or another viral illness during a mother’s early pregnancy

- Alcohol consumption during pregnancy

- Poorly controlled diabetes during pregnancy

- Smoking during pregnancy

- Certain medications taken during pregnancy — talk to your doctor before taking any drugs while you’re pregnant or trying to become pregnant

- Having a parent who had a congenital heart defect.

AV canal defect prevention

Atrioventricular canal defect generally can’t be prevented.

Heredity may play a role in some heart defects. If you have a family history of heart defects or if you already have a child with a congenital heart defect, talk with a genetic counselor and a cardiologist before getting pregnant again.

Immunization with rubella vaccine has been one of the most effective preventive strategies against congenital heart defects.

AV canal defect symptoms

Atrioventricular canal defect can involve only the two upper chambers of the heart (partial) or all four chambers (complete). In either type, extra blood circulates in the lungs.

AV canal defect is often associated with Down syndrome. A child with AV canal defect may breathe faster and harder than normal. Infants may have trouble feeding and growing at a normal rate. Symptoms may not occur until several weeks after birth. High pressure may occur in the blood vessels in the lungs because more blood than normal is being pumped there. Over time this causes permanent damage to the lung blood vessels.

In some infants, the common valve between the upper and lower chambers doesn’t close properly. This lets blood leak backward from the heart’s lower chambers to the upper ones. This leak, called regurgitation or insufficiency, can make the heart work harder and the heart becomes enlarged from working too hard.

Complete atrioventricular canal defect symptoms

Signs and symptoms usually develop in the first several weeks of life. These signs and symptoms are generally similar to those associated with heart failure and might include:

- Difficulty breathing or rapid breathing

- Wheezing

- Fatigue

- Lack of appetite

- Poor weight gain

- Pale skin color

- Bluish discoloration of the lips and skin

- Excessive sweating

- Irregular or rapid heartbeat

- Swelling in the legs, ankles and feet (edema)

Partial atrioventricular canal defect symptoms

Signs and symptoms might not appear until early adulthood and might be related to complications that develop as a result of the defect. These signs and symptoms can include:

- Abnormal heartbeat (arrhythmia)

- Shortness of breath

- High blood pressure in the lungs (pulmonary hypertension)

- Heart valve problems

- Heart failure.

AV canal defect complications

Complications of atrioventricular canal defect can include:

- Enlargement of the heart. Increased blood flow through the heart forces it to work harder than normal, causing it to enlarge.

- Pulmonary hypertension. When there is a hole (defect) that allows mixing of oxygenated (red) and deoxygenated (blue) blood, the amount of blood that goes to the lungs is increased. This results in pressure buildup in the lungs, causing high blood pressure in the lungs.

- Respiratory tract infections. Atrioventricular canal defect can cause recurrent bouts of lung infections.

- Heart failure. Untreated, atrioventricular canal defect usually results in the heart’s inability to pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs.

Complications later in life

Treatment greatly improves the outlook for children with atrioventricular canal defect. However, some children who have corrective surgery may still be at risk later in life of:

- Leaky heart valves

- Narrowing of the heart valves

- Abnormal heart rhythm

- Breathing difficulties associated with lung damage

Common signs and symptoms of these complications include:

- Shortness of breath

- Fatigue

- Rapid, fluttering heartbeat

Additional surgery might be needed to correct complications of atrioventricular canal defect.

AV canal defect diagnosis

Atrioventricular canal defect might be detected before birth through ultrasound and special heart imaging.

After birth, signs and symptoms of complete atrioventricular canal defect are usually noticeable within the first few weeks. When listening to your baby’s heart, your doctor might hear an abnormal whooshing sound (heart murmur) caused by turbulent blood flow.

If your baby is experiencing the signs and symptoms of atrioventricular canal defect, your doctor might recommend:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). Electrical signals are recorded as they travel through the heart. Your doctor can look for patterns that indicate abnormal heart function.

- Echocardiogram. Sound waves produce live-action images of the heart. Echocardiogram can reveal a hole in the heart and abnormal heart valves, as well as abnormal blood flow through the heart.

- Chest X-ray. The image can show evidence of an enlarged heart.

- Cardiac catheterization. A thin, flexible tube (catheter) is inserted into a blood vessel in the groin and up to the heart. A dye injected through the catheter makes the heart structures visible on

- X-ray pictures. The catheter also allows the doctor to measure pressure in the chambers of the heart and in the blood vessels.

AV canal defect treatment

An AV canal can be fixed. Open-heart surgery is needed to repair the defect. Unlike some other types of septal defects, the AV canal defect can’t close on its own. Medicines may be used temporarily to help with symptoms, but they don’t cure the defect or prevent permanent damage to the lung arteries.

In an infant with severe symptoms or high blood pressure in the lungs, surgery must usually be done in infancy. The surgery to fix these defects involves patching the atrial septal defect and the ventricular septal defect and repairing the heart valve. During the operation, the surgeon closes the large hole with one or two patches. Later the patch will become a permanent part of the heart as the heart’s lining grows over it. To repair the single valve, the surgeon divides the single valve between the heart’s upper and lower chambers and makes two separate valves. These will be made as close to normal valves as possible.

If an infant is very ill, or has a defect that may be too complex to repair in infancy, a temporary operation to relieve symptoms and high pressure in the lungs may be needed before the definitive operation. This procedure (pulmonary artery banding) narrows the pulmonary artery to reduce the blood flow to the lungs. When the child is older, an operation is done to remove the band and fix the AV canal defect with open-heart surgery.

Surgical repair of an AV canal usually restores blood circulation to normal. For many patients, the long-term outlook is good, and no medicines or additional surgery are needed. Because this is a more complicated congenital heart defect, late problems in adults are more common than after an atrial septal defect or ventricular septal defect is closed. As the child grows, the repair may partially break down leading to patch leaks, valve leakage and narrowing of the blood flow channel to the body. These problems may increase the workload of the heart and cause symptoms.

Figure 4. Repair of atrioventricular septal defect

After surgery

If the heart defect is repaired successfully, your child will likely lead a normal life, often with no activity restrictions.

However, you or your child will need lifelong follow-up care with a cardiologist trained in congenital heart disease. Your cardiologist will likely recommend a follow-up exam once a year or more frequently if problems, such as a leaky heart valve, remain. Adults whose congenital heart defects were treated as children may need care from a cardiologist trained in adult congenital heart disease (adult congenital cardiologist) throughout life. Special attention and care may be needed around the time of procedures, such as an operation which does not involve the heart.

You or your child might also need to take preventive antibiotics before certain dental and other surgical procedures if he or she:

- Has remaining heart defects after surgery

- Received an artificial heart valve

- Received artificial (prosthetic) material during heart repair

The antibiotics are used to prevent a bacterial infection of the lining of the heart (endocarditis).

Many people who have corrective surgery for atrioventricular canal defect don’t need additional surgery. However, some complications, such as heart valve leaks, may require treatment.

What if the AV canal defect is still present? Should it be repaired in adulthood?

The decision to repair an AV canal defect in adulthood is complicated. It depends on the pressures in the lung and the heart’s pumping function. However, when the pressures aren’t too high and the pump function is good, these defects can be repaired and adult patients are likely to improve. A heart catheterization is almost always required to know whether the defect should be closed. These defects can’t be closed or repaired in the catheterization laboratory, however, because of their location and the need to fix the heart valves.

Problems you may have

Problems in patients with repaired AV canals depend on whether there are patch leaks and whether there’s a lot of valve regurgitation. Shortness of breath, inability to exercise and swelling in the legs are all signs of heart failure. Abnormal heart rhythms may cause palpitations (skipped or rapid heartbeats) and, rarely, fainting. Some patients may need a pacemaker after the repair if the electrical system has been damaged.

Patients with unrepaired AV canal are often blue (see Eisenmenger’s syndrome). Because of valve leaks on the heart’s left side, they’re more likely to have heart failure than other patients with Eisenmenger’s syndrome, due to ASDs and VSDs.

What activities can my child do?

If the AV canal defect has been closed with surgery, your child may not need any special precautions regarding physical activities and may be able to participate in normal activities without increased risk. Being physically active is healthy for the cardiovascular system, but some children may need to limit their activity. However, patients with heart failure and pulmonary hypertension may need some restrictions. Discuss this with your child’s pediatric cardiologist.

What will my child need in the future?

After surgery your child must be examined regularly by a pediatric cardiologist. More medical or surgical treatment is sometimes needed.

Surgical repair of an AV canal usually restores the blood circulation to normal. However, the reconstructed valve may not work normally. The valve structures can leak or narrow. But, for many children, the long-term outlook is good, and usually no medicines or additional surgery are needed.

Ongoing care

An adult with a repaired or unrepaired AV canal defect must be examined regularly by a cardiologist with experience in adult congenital heart disease. The frequency of the visits depends on the extent of problems with the repair, the presence of abnormal heart rhythms and pulmonary hypertension. In general, you should visit the cardiologist at least once a year. You should also consult a cardiologist with expertise in care of adult congenital heart disease if you’re undergoing any type of non-heart surgery or invasive procedure or thinking about heart surgery.

Medical therapy

Heart failure medications may be needed, especially in patients with valve regurgitation, to help their heart pump better and/or lower blood pressure. Patients with pulmonary hypertension may also require medications. Your cardiologist can monitor you with noninvasive tests if needed. These include electrocardiograms, Holter monitors, exercise stress tests and echocardiograms. When further surgery is contemplated, a heart catheterization is almost always needed.

What about preventing endocarditis?

Children with AV canal defect may risk endocarditis both before and after repair. Lifelong endocarditis prophylaxis is recommended. Ask about your child’s risk of endocarditis and about your child’s need to take antibiotics before certain dental procedures.

Infective endocarditis

Infective endocarditis also called bacterial endocarditis, is an infection caused by bacteria that enter the bloodstream and settle in the heart lining, a heart valve or a blood vessel. Infective endocarditis is uncommon, but people with some heart conditions have a greater risk of developing it.

Dental procedures and infective endocarditis

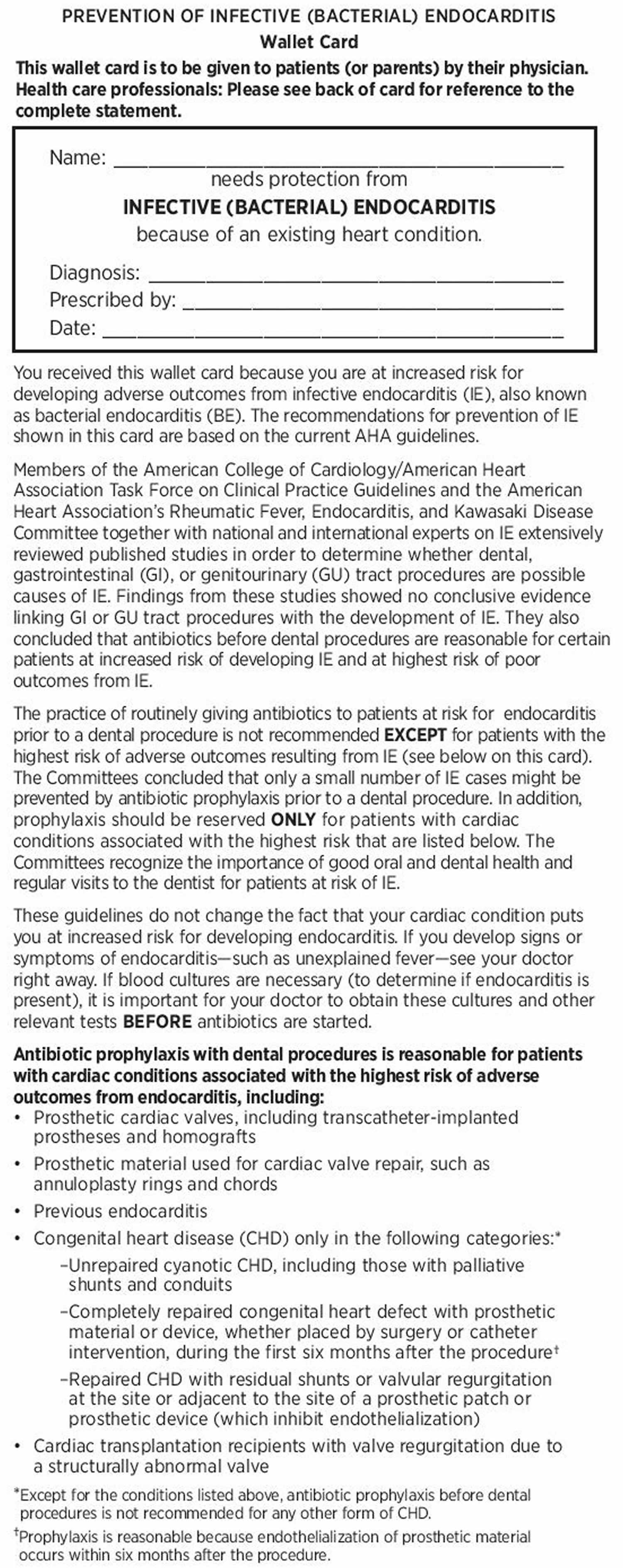

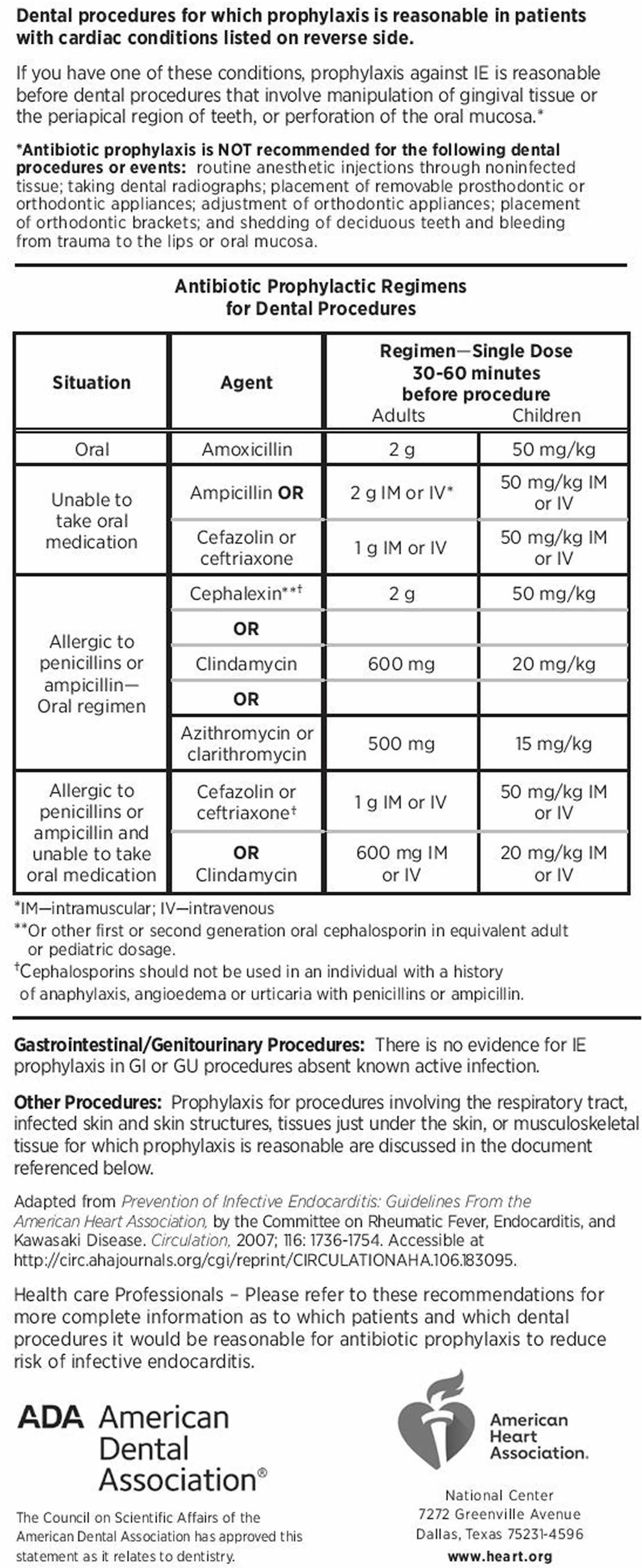

In the past, patients with nearly every type of congenital heart defect needed to receive antibiotics one hour before dental procedures or operations on the mouth, throat, gastrointestinal genital, or urinary tract. However, in 2007 the American Heart Association simplified its recommendations. Today, antibiotics before dental procedures are only recommended for patients with the highest risk of infective endocarditis, those who have 1:

- A prosthetic heart valve or who have had a heart valve repaired with prosthetic material.

- A history of endocarditis.

- A heart transplant with abnormal heart valve function

- Certain congenital heart defects including:

- Cyanotic congenital heart disease (birth defects with oxygen levels lower than normal), that has not been fully repaired, including children who have had a surgical shunts and conduits.

- A congenital heart defect that’s been completely repaired with prosthetic material or a device for the first six months after the repair procedure. Prophylaxis is reasonable because endothelialization of prosthetic material occurs within six months after the procedure.

- Repaired congenital heart disease with residual defects, such as persisting leaks or abnormal flow at or adjacent to a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device.

Key changes for patients with congenital heart defects

Preventive antibiotics are no longer recommended for any other congenital heart disease than these:

- Cyanotic congenital heart disease (birth defects with oxygen levels lower than normal), that has not been fully repaired, including children who have had a surgical shunts and conduits.

- A congenital heart defect that’s been completely repaired with prosthetic material or a device for the first six months after the repair procedure. Prophylaxis is reasonable because endothelialization of prosthetic material occurs within six months after the procedure.

- Repaired congenital heart disease with residual defects, such as persisting leaks or abnormal flow at or adjacent to a prosthetic patch or prosthetic device.

Additionally, taking antibiotics just to prevent endocarditis is not recommended for patients who have procedures involving the reproductive, urinary or gastrointestinal tracts.

If you still require antibiotic prophylaxis for dental treatment or oral surgery, your cardiologist may give you an American Heart Association wallet card (see Figure 5 below).

Show this card to your dentist, pediatrician, family doctor or other physician. It advises them to give you the proper antibiotic and dose. For smaller children, the dose will vary according to the child’s weight. Always remind the dentist or doctor if you (or your child) are allergic to any antibiotics or other medications. Brushing, flossing, and visiting your dentist regularly helps keep your smile bright and prevents tooth and gum infections that could lead to endocarditis.

Your cardiologist can provide you more information and can answer your questions about preventing endocarditis.

Figure 5. American Heart Association prevention of infective endocarditis

Pregnancy

Women who had an atrioventricular canal defect that was surgically corrected before any permanent lung damage occurred can generally expect to have normal pregnancies. If there are problems like a leaking valve or irregular heart rhythms, you may be at increased risk for complications of pregnancy. If you have heart failure or pulmonary hypertension, pregnancy isn’t recommended. Women with unrepaired AV canal defects or who have leftover problems should talk to their cardiologist before deciding to get pregnant. See the sections on Pregnancy and on Genetic Counseling for more information. Pregnant women with repaired AV canal defects who are free of significant problems may not require high risk obstetrical care. In contrast those unrepaired AV canal defects, significant valve leaks or pulmonary hypertension.

Evaluation by a cardiologist trained in congenital heart disease (adult congenital cardiologist) is recommended for women with repaired or unrepaired atrioventricular canal defect before they attempt pregnancy.

Will I need more surgery?

The function of the repaired valves is a long-term concern. Some patients will need their valve replaced with a mechanical one when they get older. It’s rare that the valve can be further repaired. Other patients may need more surgery to close patch leaks.

References