Mitral valve regurgitation

Mitral valve regurgitation also called mitral valve insufficiency, mitral regurgitation, mitral incompetence or leaky mitral valve, is a disorder in which the mitral valve on the left side of the heart does not close properly allowing blood to flow backward in your heart. The mitral valve is one of the two main valves on the left side of your heart. The mitral valve is located between the upper left heart chamber (left atrium) and the lower left heart chamber (left ventricle). Normally, the mitral valve has two flaps (leaflets) that open and close, allowing blood to flow from your left atrium to your left ventricle and preventing it from flowing backward into the left atrium and lungs.

Regurgitation means leaking from a valve that does not close all the way. A leaky mitral valve doesn’t close the way it should, allowing some blood to flow backward into the left atrium from the lower chamber as it contracts. This cuts down on the amount of blood that flows to the rest of the body. As a result, the heart may try to pump harder. If the mitral valve regurgitation is significant, blood can’t move through your heart or to the rest of your body as efficiently, making you feel tired or out of breath. If left untreated, a leaky mitral valve could lead to heart failure (congestive heart failure).

Mitral regurgitation may begin suddenly. This often occurs after a heart attack. When the regurgitation does not go away, it becomes long-term (chronic).

Many other diseases or problems can weaken or damage the mitral valve or the heart tissue around the valve. You are at risk for mitral valve regurgitation if you have:

- Coronary heart disease and high blood pressure

- Infection of the heart valves

- Mitral valve prolapse

- Rare conditions, such as untreated syphilis or Marfan syndrome

- Rheumatic heart disease. This is a complication of untreated strep throat that is becoming less common.

- Swelling of the left lower heart chamber

Another important risk factor for mitral regurgitation is past use of a diet pill called “Fen-Phen” (fenfluramine and phentermine) or dexfenfluramine. The drug was removed from the market by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 1997 because of safety concerns.

Treatment of mitral valve regurgitation depends on how severe your condition is, whether it’s getting worse and whether you have symptoms. For mild leakage, treatment is usually not necessary.

You may need heart surgery to repair or replace the valve for severe leakage or regurgitation. Left untreated, severe mitral valve regurgitation can cause heart failure or heart rhythm problems (arrhythmias). Even people without symptoms may need to be evaluated by a cardiologist and surgeon trained in mitral valve disease to determine whether early intervention may be beneficial.

See your doctor if symptoms get worse or do not improve with treatment.

Also see your doctor if you are being treated for mitral valve insufficiencyand develop signs of infection, which include:

- Chills

- Fever

- General ill feeling

- Headache

- Muscle aches

What are heart valves ?

Your heart is a strong muscle about the size of the palm of your hand. Your body depends on the heart’s pumping action to deliver oxygen- and nutrient-rich blood to the body’s cells. When the cells are nourished properly, the body can function normally. Just like an engine makes a car go, the heart keeps your body running. The heart has two pumps separated by an inner wall called the septum. The right side of the heart pumps blood to the lungs to pick up oxygen. The left side of the heart receives the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and pumps it to the body.

The heart has four chambers 1, two on the right and two on the left:

- Two upper chambers are called atrium (two is called an atria). The atria collect blood as it flows into the heart.

- Two lower chambers are called ventricles. The ventricles pump blood out of the heart to the lungs or other parts of the body.

The heart also has four valves that open and close to let blood flow from the atria to the ventricles and from the ventricles into the two large arteries connected to the heart in only one direction when the heart contracts (beats). The four heart valves are:

- Tricuspid valve, located between the right atrium and right ventricle

- Pulmonary or pulmonic valve, between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery. This artery carries blood from the heart to the lungs.

- Mitral valve, between the left atrium and left ventricle

- Aortic valve, between the left ventricle and the aorta. This aorta carries blood from the heart to the body.

Each valve has a set of flaps (also called leaflets or cusps). The mitral valve has two flaps; the others have three. Valves are like doors that open and close. They open to allow blood to flow through to the next chamber or to one of the arteries. Then they shut to keep blood from flowing backward. Blood flow occurs only when there’s a difference in pressure across the valves, which causes them to open. Under normal conditions, the valves permit blood to flow in only one direction.

The heart four chambers and four valves and is connected to various blood vessels. Veins are blood vessels that carry blood from the body to the heart. Arteries are blood vessels that carry blood away from the heart to the body.

The heart pumps blood to the lungs and to all the body’s tissues by a sequence of highly organized contractions of the four chambers. For the heart to function properly, the four chambers must beat in an organized way.

When the heart’s valves open and close, they make a “lub-DUB” sound that a doctor can hear using a stethoscope 2.

- The first sound—the “lub”—is made by the mitral and tricuspid valves closing at the beginning of systole. Systole is when the ventricles contract, or squeeze, and pump blood out of the heart.

- The second sound—the “DUB”—is made by the aortic and pulmonary valves closing at the beginning of diastole. Diastole is when the ventricles relax and fill with blood pumped into them by the atria.

Figure 1. The anatomy of the heart valves

Figure 2. Top view of the 4 heart valves

Figure 3. Normal heart blood flow

Figure 4. Heart valves function

Stages of mitral valve regurgitation

The 2014 American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association valve guidelines 3 introduced stages for each valve lesion, which are similar to the stages proposed in the Heart Failure guidelines. Each stage describes the progression of the valvular disorder taking into account the presence or absence of symptoms, the severity of the valve disorder, the response of the left ventricle to the effect of the disorder, the effect on pulmonary circulation and heart rhythm. The staging system provides the physician a better way to monitor the progression of the valvular disease, defines the clinical and echocardiographic follow-up and helps make management decisions based on the stage of the disorder in order to treat complications and effects of the disorder in a more timely fashion. Table 1 provides a summary of the stages proposed for primary mitral regurgitation.

Table 1. Stages of primary mitral regurgitation

| Grade | Definition | Valve Anatomy | Valve Hemodynamics* | Hemodynamic Consequences | Symptoms |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | At risk of mitral regurgitation | • Mild mitral valve prolapse with normal coaptation • Mild valve thickening and leaflet restriction | • No mitral regurgitation jet or small central jet area <20% LA on Doppler • Small vena contracta <0.3 cm | • None | • None |

| B | Progressive mitral regurgitation | • Severe mitral valve prolapse with normal coaptation • Rheumatic valve changes with leaflet restriction and loss of central coaptation • Prior infective endocarditis | • Central jet mitral regurgitation 20%-40% LA or late systolic eccentric jet mitral regurgitation • Vena contracta <0.7 cm • Regurgitant volume <60 mL • Regurgitant fraction <50% • ERO <0.40 cm2 • Angiographic grade 1–2+ | • Mild LA enlargement • No LV enlargement • Normal pulmonary pressure | • None |

| C | Asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation | • Severe mitral valve prolapse with loss of coaptation or flail leaflet • Rheumatic valve changes with leaflet restriction and loss of central coaptation • Prior infective endocarditis • Thickening of leaflets with radiation heart disease | • Central jet mitral regurgitation >40% LA or holosystolic eccentric jet mitral regurgitation • Vena contracta ≥0.7 cm • Regurgitant volume ≥60 mL • Regurgitant fraction ≥50% • ERO 0.40 cm2 • Angiographic grade 3–4+ | • Moderate or severe LA enlargement • LV enlargement • Pulmonary hypertension may be present at rest or with exercise • C1: LVEF >60% and LVESD <40 mm • C2: LVEF ≤60% and LVESD ≥40 mm | • None |

| D | Symptomatic severe mitral regurgitation | • Severe mitral valve prolapse with loss of coaptation or flail leaflet • Rheumatic valve changes with leaflet restriction and loss of central coaptation • Prior infective endocarditis • Thickening of leaflets with radiation heart disease | • Central jet mitral regurgitation >40% LA or holosystolic eccentric jet mitral regurgitation • Vena contracta ≥0.7 cm • Regurgitant volume ≥60 mL • Regurgitant fraction ≥50% • ERO 0.40 cm2 • Angiographic grade 3–4+ | • Moderate or severe LA enlargement • LV enlargement • Pulmonary hypertension present | • Decreased exercise tolerance • Exertional dyspnea |

Footnotes: *Several valve hemodynamic criteria are provided for assessment of mitral regurgitation severity, but not all criteria for each category will be present in each patient. Categorization of MR severity as mild, moderate, or severe depends on data quality and integration of these parameters in conjunction with other clinical evidence.

Abbreviations: ERO = effective regurgitant orifice; IE = infective endocarditis; LA = left atrium/atrial; LV = left ventricular; LVEF = left ventricular ejection fraction; LVESD = left ventricular end-systolic dimension; MR = mitral regurgitation

[Source 3 ]Causes of mitral regurgitation

Mitral valve regurgitation is the most common type of heart valve disorder.

Blood that flows between different chambers of your heart must flow through a valve. The valve between the 2 chambers on the left side of your heart is called the mitral valve.

In mitral valve regurgitation, the valve between the upper left heart chamber (left atrium) and the lower left heart chamber (left ventricle) doesn’t close tightly, causing blood to leak backward into the left atrium (regurgitation).

Mitral valve regurgitation causes

Mitral valve regurgitation can be caused by problems with the mitral valve, also called primary mitral valve regurgitation. Diseases of the left ventricle can lead to secondary or functional mitral valve regurgitation.

Possible causes of mitral valve regurgitation include:

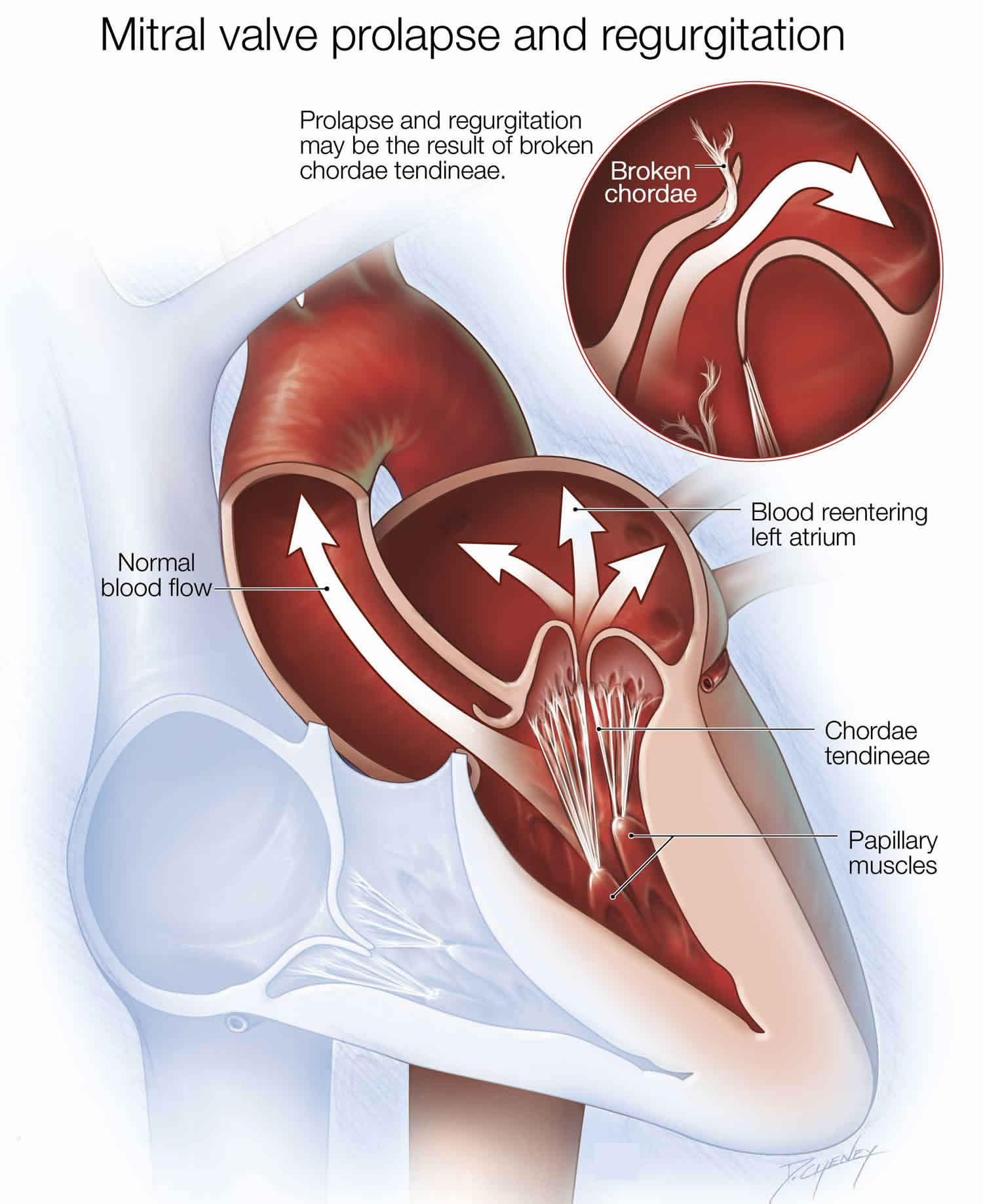

- Mitral valve prolapse. In this condition, the mitral valve’s leaflets bulge back into the left atrium during the heart’s contraction. This common heart defect can prevent the mitral valve from closing tightly and lead to regurgitation.

- Damaged tissue cords. Over time, the tissue cords that anchor the flaps of the mitral valve to the heart wall may stretch or tear, especially in people with mitral valve prolapse. A tear can cause leakage through the mitral valve suddenly and may require repair by heart surgery. Trauma to the chest also can rupture the cords.

- Rheumatic fever. Rheumatic fever — a complication of untreated strep throat — can damage the mitral valve, leading to mitral valve regurgitation early or later in life. Rheumatic fever is now rare in the United States, but it’s still common in developing countries.

- Endocarditis. The mitral valve may be damaged by an infection of the lining of the heart (endocarditis) that can involve heart valves.

- Heart attack. A heart attack can damage the area of the heart muscle that supports the mitral valve, affecting the function of the valve. If the damage is extensive enough, a heart attack can cause sudden and severe mitral valve regurgitation.

- Abnormality of the heart muscle (cardiomyopathy). Over time, certain conditions, such as high blood pressure, can cause your heart to work harder, gradually enlarging your heart’s left ventricle. This can stretch the tissue around your mitral valve, which can lead to leakage.

- Trauma. Experiencing trauma, such as in a car accident, can lead to mitral valve regurgitation.

- Congenital heart defects. Some babies are born with defects in their hearts, including damaged heart valves.

- Certain drugs. Prolonged use of certain medications can cause mitral valve regurgitation, such as those containing ergotamine (Cafergot, Migergot) that are used to treat migraines and other conditions.

- Radiation therapy. In rare cases, radiation therapy for cancer that is focused on the chest area can lead to mitral valve regurgitation.

- Atrial fibrillation. Atrial fibrillation is a common heart rhythm problem that can be a potential cause of mitral valve regurgitation.

Risk factors for mitral valve insufficiency

Several factors can increase your risk of mitral valve regurgitation, including:

- A history of mitral valve prolapse or mitral valve stenosis. However, having either condition doesn’t necessarily mean you’ll develop mitral valve regurgitation. A family history of valve disease also can increase risk.

- A heart attack. A heart attack can damage your heart, affecting the function of the mitral valve.

- Heart disease. Certain forms of heart disease, such as coronary artery disease, can lead to mitral valve regurgitation.

- Use of certain medications. People who take drugs containing ergotamine (Cafergot, Migergot) and similar medicines for migraines or who take cabergoline have an increased risk of mitral regurgitation. Similar problems were noted with the appetite suppressants fenfluramine and dexfenfluramine, which are no longer sold.

- Infections such as endocarditis or rheumatic fever. Infections or the inflammation they cause can damage the mitral valve.

- Congenital heart disease. Some people are born with an abnormal mitral valve prone to regurgitation.

- Age. By middle age, many people have some mitral valve regurgitation caused by natural deterioration of the valve.

Mitral valve insufficiency prevention

People with abnormal or damaged heart valves are at risk for an infection called endocarditis. Anything that causes bacteria to get into your bloodstream can lead to this infection. Steps to avoid this problem include:

- Avoid unclean injections.

- Treat strep infections quickly to prevent rheumatic fever.

- Always tell your doctor and dentist if you have a history of heart valve disease or congenital heart disease before treatment. Some people may need antibiotics before dental procedures or surgery.

Mitral valve regurgitation symptoms

Some people with mitral valve disease might not experience symptoms for many years. Signs and symptoms of mitral valve regurgitation, which depend on its severity and how quickly the condition develops, can include:

- Abnormal heart sound (heart murmur) heard through a stethoscope

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea), especially when you have been very active or when you lie down

- Fatigue

- Heart palpitations — sensations of a rapid, fluttering heartbeat

- Swollen feet or ankles

- Cough

- Fatigue, exhaustion, and lightheadedness

- Rapid breathing

- Waking up an hour or so after falling asleep because of trouble breathing

- Urination, excessive at night

Symptoms may begin suddenly if:

- A heart attack damages the muscles around the mitral valve.

- The cords that attach the muscle to the valve break.

- An infection of the valve destroys part of the valve.

Mitral valve regurgitation is often mild and progresses slowly. You may have no symptoms for many years and be unaware that you have this condition, and it might not progress.

Your doctor might first suspect you have mitral valve regurgitation upon detecting a heart murmur. Sometimes, however, the problem develops quickly, and you may experience a sudden onset of severe signs and symptoms.

Mitral valve regurgitation complications

When it’s mild, mitral valve regurgitation usually does not cause any problems. However, severe mitral valve regurgitation can lead to complications, including:

- Heart failure. Heart failure results when your heart can’t pump enough blood to meet your body’s needs. Severe mitral valve regurgitation places an extra strain on the heart because, with blood pumping backward, there is less blood going forward with each beat. The left ventricle gets bigger and, if untreated, weakens. This can cause heart failure. Also, pressure builds in your lungs, leading to fluid accumulation, which strains the right side of the heart.

- Atrial fibrillation. The stretching and enlargement of your heart’s left atrium may lead to this heart rhythm irregularity in which the upper chambers of your heart beat chaotically and rapidly. Atrial fibrillation can cause blood clots, which can break loose from your heart and travel to other parts of your body, causing serious problems, such as a stroke if a clot blocks a blood vessel in your brain.

- Pulmonary hypertension. If you have long-term untreated or improperly treated mitral regurgitation, you can develop a type of high blood pressure that affects the vessels in the lungs (pulmonary hypertension). A leaky mitral valve can increase pressure in the left atrium, which can eventually cause pulmonary hypertension. This can lead to heart failure on the right side of the heart.

Mitral valve regurgitation diagnosis

Your doctor will ask about your medical history and your family history of heart disease. Your doctor will also perform a physical exam that includes listening to your heart with a stethoscope. Mitral valve regurgitation usually produces a sound of blood leaking backward through the mitral valve (heart murmur).

When listening to your heart and lungs, your doctor may detect:

- A thrill (vibration) over the heart when feeling the chest area

- An extra heart sound (S4 gallop)

- A distinctive heart murmur

- Crackles in the lungs (if fluid backs up into the lungs)

The physical exam may also reveal:

- Ankle and leg swelling

- Enlarged liver

- Bulging neck veins

- Other signs of right-sided heart failure

Your doctor will then decide which tests are needed to make a diagnosis. For testing, you may be referred to a cardiologist.

Common tests to diagnose mitral valve regurgitation include:

- Echocardiogram. This test is commonly used to diagnose mitral valve regurgitation. In this test, sound waves directed at your heart from a wandlike device (transducer) held on your chest produce video images of your heart in motion. This test assesses the structure of your heart, the mitral valve and the blood flow through your heart. An echocardiogram helps your doctor get a close look at the mitral valve and how well it’s working. Doctors also may use a 3-D echocardiogram. Doctors may conduct another type of echocardiogram called a transesophageal echocardiogram. In this test, a small transducer attached to the end of a tube is inserted down your esophagus, which allows a closer look at the mitral valve than a regular echocardiogram does.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG). Wires (electrodes) attached to adhesive pads on your skin measure electrical impulses from your heart. An ECG can detect enlarged chambers of your heart, heart disease and abnormal heart rhythms.

- Chest X-ray. This enables your doctor to determine whether the left atrium or the left ventricle is enlarged — possible indicators of mitral valve regurgitation — and the condition of your lungs.

- Cardiac MRI. A cardiac MRI uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of your heart. This test may be used to determine the severity of your condition and assess the size and function of your lower left heart chamber (left ventricle).

- Cardiac CT. A CT angiogram may be performed of the chest, abdomen and pelvis to determine whether you’re a candidate for robotic mitral valve repair.

- Exercise tests or stress tests. Different exercise tests help measure your activity tolerance and monitor your heart’s response to physical exertion. If you are unable to exercise, medications to mimic the effect of exercise on your heart may be used.

- Cardiac catheterization. This test isn’t often used to diagnose mitral valve regurgitation. This invasive technique involves threading a thin tube (catheter) through a blood vessel in your arm or groin to an artery in your heart and injecting dye through the catheter to make the artery visible on an X-ray. This provides a detailed picture of your heart arteries and how your heart functions. It can also measure the pressure inside the heart chambers.

Mitral valve regurgitation treatment

Mitral valve regurgitation treatment depends on how severe your condition is, if you’re experiencing signs and symptoms, what condition caused the mitral valve regurgitation, how well the heart is working, if the heart has become enlarged and if your condition is getting worse. The goal of treatment is to improve your heart’s function while minimizing your signs and symptoms and avoiding future complications.

A doctor trained in heart disease (cardiologist) will provide your care. If you have mitral valve regurgitation, consider being treated at a medical center with a multidisciplinary team of doctors and medical staff trained and experienced in evaluating and treating heart valve disease. This team can work closely with you to determine the most appropriate treatment for your condition.

Watchful waiting

Some people, especially those with mild regurgitation, might not need treatment. However, the condition may require monitoring by your doctor. You may need regular evaluations, with the frequency depending on the severity of your condition. Your doctor may also recommend making healthy lifestyle changes.

Medications

People with high blood pressure or a weakened heart muscle may be given medicines to reduce the strain on the heart and ease symptoms.

Your doctor may prescribe medication to treat symptoms, although medication can’t treat mitral valve regurgitation.

Medications may include:

- Water pills (diuretics). These medications can relieve fluid accumulation in your lungs or legs, which can accompany mitral valve regurgitation.

- Blood thinners (anticoagulants). These medications can help prevent blood clots and may be used if you have atrial fibrillation.

- High blood pressure medications such as beta-blockers, ACE inhibitors, or calcium channel blockers. High blood pressure makes mitral valve regurgitation worse, so if you have high blood pressure, your doctor may prescribe medication to help lower it.

- Drugs that help control uneven or abnormal heartbeats

A low-sodium diet may be helpful. You may need to limit your activity if symptoms develop.

Surgery

Your mitral valve may need to be repaired or replaced. Doctors may suggest mitral valve repair or replacement even if you aren’t experiencing symptoms, as this may prevent complications and improve outcomes. If you need surgery for another heart condition, your doctor may repair or replace the diseased mitral valve at the same time.

Mitral valve surgery is usually performed through a cut (incision) in the chest. In some cases, doctors may conduct minimally invasive heart surgery, which involves the use of smaller incisions than those used in open-heart surgery.

Doctors at some medical centers may perform robot-assisted heart surgery, a type of minimally invasive heart surgery. In this type of surgery, surgeons view the heart in a magnified high-definition 3-D view on a video monitor and use robotic arms to duplicate specific maneuvers used in open-heart surgeries.

Your doctor will discuss with you whether mitral valve repair or mitral valve replacement may be most appropriate for your condition. He or she may also evaluate you to determine whether you’re a candidate for minimally invasive heart surgery or open-heart surgery.

Doctors often may recommend mitral valve repair, as it preserves your own valve and may preserve heart function. However, if mitral valve repair isn’t possible, doctors may need to perform mitral valve replacement.

Surgery options include:

Mitral valve repair

Surgeons can repair the valve by reconnecting valve flaps (leaflets), replacing the cords that support the valve, or removing excess valve tissue so that the leaflets can close tightly. Surgeons may often tighten or reinforce the ring around a valve (annulus) by implanting an artificial ring (annuloplasty band).

Doctors may use long, thin tubes (catheters) to repair the mitral valve in some cases. In one catheter procedure, doctors insert a catheter with a clip attached in an artery in the groin and guide it to the mitral valve. Doctors use the clip to reshape the valve. People who have severe symptoms of mitral valve regurgitation and who aren’t candidates for surgery or who have high surgical risk may be considered for this procedure.

In another procedure, doctors may repair a previously replaced mitral valve that is leaking by inserting a device to plug the leak.

Mitral valve replacement

If your mitral valve can’t be repaired, you may need mitral valve replacement. In mitral valve replacement, your surgeon removes the damaged valve and replaces it with a mechanical valve or a valve made from cow, pig or human heart tissue (biological tissue valve).

Biological tissue valves degenerate over time, and often eventually need to be replaced. People with mechanical valves need to take blood-thinning medications for life to prevent blood clots.

Your doctor can discuss the risks and benefits of each type of heart valve with you and discuss which valve may be appropriate for you.

Doctors continue to study catheter procedures to repair or replace mitral valves. Some medical centers may offer mitral valve replacement during a catheter procedure as part of a clinical trial for people with severe mitral valve disease who are aren’t candidates for surgery. A catheter procedure can also be used to insert a replacement valve in a biological tissue replacement valve that is no longer working properly.

Talk to your doctor about what type of follow-up you need after surgery, and let your doctor know if you develop new symptoms or if your symptoms worsen after treatment.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Your doctor may suggest you incorporate several heart-healthy lifestyle changes into your life, including:

- Keeping your blood pressure under control. Control of high blood pressure is important if you have mitral valve regurgitation.

- Eating a heart-healthy diet. Food doesn’t directly affect mitral valve regurgitation. But a healthy diet can help prevent other heart disease that can weaken the heart muscle. Eat foods that are low in saturated and trans fats, sugar, salt, and refined grains, such as white bread. Eat a variety of vegetables and fruits, whole grains, and proteins, such as lean meats, fish and nuts.

- Maintaining a healthy weight. Keep your weight within a range recommended by your doctor.

- Preventing infective endocarditis. If you have had a heart valve replaced, your doctor may recommend you take antibiotics before dental procedures to prevent an infection called infective endocarditis. Check with your doctor to find out if he or she recommends that you take antibiotics before dental procedures.

- Cutting back on alcohol. Heavy alcohol use can cause arrhythmias and can make your symptoms worse. Excessive alcohol use can also cause cardiomyopathy, a condition of weakened heart muscle that leads to mitral regurgitation. Ask your doctor about the effects of drinking alcohol.

- Avoiding tobacco. If you smoke, quit. Ask your doctor about resources to help you quit smoking. Joining a support group may be helpful.

- Getting regular physical activity. How long and hard you’re able to exercise depends on the severity of your condition and the intensity of exercise. Ask your doctor for guidance before starting to exercise, especially if you’re considering competitive sports.

- Seeing your doctor regularly. Establish a regular evaluation schedule with your cardiologist or primary care provider. Tell your doctor if you have any changes in your signs or symptoms.

If you’re a woman with mitral valve regurgitation, it’s important to talk to your doctor before you become pregnant. Pregnancy causes the heart to work harder. How a heart with mitral valve regurgitation tolerates this extra work depends on the degree of regurgitation and how well your heart pumps. Throughout your pregnancy and after delivery, your cardiologist and obstetrician should monitor you.

Coping and support

If you have mitral valve regurgitation, here are some steps that may help you cope:

- Take medications as prescribed. Take your medications as directed by your doctor.

- Get support. Having support from your family and friends can help you cope with your condition. Ask your doctor about support groups that may be helpful.

- Stay active. It’s a good idea to stay physically active. Your doctor may give you recommendations about how much and what type of exercise is appropriate for you.

Mitral valve regurgitation prognosis

Mitral valve regurgitation outcome varies. Most of the time mitral valve regurgitation is mild, so no therapy or restriction is needed. Symptoms can most often be controlled with medicine.

Table 2 summarizes the clinical, biologic and echocardiographic predictors of poor outcome in patients with primary mitral regurgitation.

Table 2. Predictors of poor outcome in primary mitral regurgitation

| Clinical Characteristics | Biologic Markers | Echo Findings |

|---|---|---|

| Advance age | Elevated BNP | Low ejection fraction (<60%) |

| Symptoms of CHF | EROA (>40 mm2) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | Left atrial volume | |

| Poor exercise capacity | Pulmonary hypertension | |

| Abnormal LV strain |

Abbreviations: CHF = congestive heart failure; BNP = B-natriuretic peptide; EROA = Effective Regurgitant Orifice Area; LV = left ventricle

The natural history of organic mitral regurgitation is highly variable and depends on a combination of parameters that include the regurgitant volume, the cause of the regurgitation and its effect on the left ventricle 4. Asymptomatic patients with mild primary mitral regurgitation usually remain stable for many years. Severe mitral regurgitation develops only is a small percentage of these patients, due to intervening infective endocarditis or chordal rupture 4.

Different series examined the natural history of patients with severe mitral regurgitation. Early series reported widely variable mortality rates, ranging from 27% to 97% at 5-year follow-up 5. That variation may be explained by poorly defined severity of mitral regurgitation, various selection biases and small study populations 6. A series from Ling et al. 7 examined 229 patients with mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflet, many of who were symptomatic, had atrial fibrillation or evidence of left ventricular dysfunction. Patients who were treated medically had a mortality rate significantly higher than the expected (6.3% yearly mortality, when compared with the expected rate in the US population according to the 1990 census). Death or need for surgery was almost unavoidable within 10 years of diagnosis and surgical correction improved long- term survival 8.

Two recent series involved patients with mitral regurgitation who were initially asymptomatic and had a normal left ventricular function 9. Enriquez-Sarano et al. 10 examined prospectively 456 patients with asymptomatic organic mitral regurgitation and showed that the 5-year mortality from any cause was 22% and the cardiac mortality was 14% in patients managed medically. Cardiac surgery was ultimately performed in 232 patients and was associated with improved survival. Rosenhek et al. 9 followed a series of 132 asymptomatic patients with severe degenerative mitral regurgitation. Survival without the need of surgery was 92% at 2 years, 78% at 4 years and 65% at 6 years. A total of 38 patients developed indications for surgery and those with a flail leaflet tended to develop criteria for surgery slightly, but not significantly earlier 9.

Despite the lack of randomized trials, all the prospective, observational data showed that in asymptomatic patients with initially preserved ejection fraction, severe mitral regurgitation has a high likelihood of requiring surgery over the next 6–10 years, because of heart failure symptoms or left ventricular dysfunction 11.

Many predictors of different clinical outcomes and especially mortality have been identified in patients with primary mitral regurgitation. Ling et al. 8 showed that in patients with mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflets, older age, presence of symptoms and lower ejection fraction are independent predictors of mortality.

Enriquez-Sarano et al. demonstrated that the Effective Regurgitant Orifice Area (EROA) is a powerful predictor of outcomes in patients with asymptomatic, organic mitral regurgitation 10. When compared to patients with EROA < 20 mm², those with an orifice of at least 40 mm2 have an increased risk of death from any cause, death from cardiac causes and cardiac events (defined as death from cardiac causes, heart failure and new atrial fibrillation).

Tourneau et al. 12 examined the impact of left atrial volume on clinical outcomes in 492 patients with organic mitral regurgitation and showed that the left atrial index is a predictor of long-term outcomes. Patients with a left atrial index ≥60 ml/m² have lower 5-year survival and more cardiac events than those with mild or no left atrial enlargement. In this cohort, mitral surgery is associated with decreased mortality and cardiac events 12.

The MIDA registry included patients with mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflets 13. Pulmonary artery systolic pressure was measured by echocardiography is 437 patients and pulmonary hypertension was observed in 102 patients. Pulmonary hypertension is an independent predictor of all- cause death, cardiovascular death and heart failure 13. In that registry, mitral valve surgery was beneficial, but it didn’t abolish completely the effects of pulmonary hypertension once it was established.

Atrial fibrillation is a common arrhythmia in patients with chronic mitral regurgitation and its onset is a marker of disease progression 14. Patients with atrial fibrillation have an adverse outcome compared to those who remain in sinus rhythm58 and the development of atrial fibrillation is considered an indication (IIa) for surgical intervention 3.

Over the past few years new prognostic markers have emerged. Those include the b- natriuretic peptide (BNP), the use of left ventricular strain 15 and the exercise capacity 16.

B-natriuretic peptide (BNP) activation in organic mitral regurgitation is primarily due to ventricular and atrial consequences, rather than the degree of mitral regurgitation 17. Higher BNP levels are associated with lower survival and higher combined adverse events (death and heart failure) 18.

Alashi et al. 19 examined 448 asymptomatic patients with severe primary mitral regurgitation and preserved ejection fraction and demonstrated that abnormal longitudinal strain and higher BNP levels are associated with higher long-term mortality and the combination of two appeared to be a synergistic outcome predictor.

The importance of exercise capacity in predicting outcomes in patients with severe primary regurgitation was studied by Naji et al 20. In 576 patients with primary mitral regurgitation who underwent exercise echocardiography prior to mitral valve surgery, lower achieved METs were associated with worse long-term outcomes. The authors concluded that achieving >100% of age and gender- predicted METs can safely delay mitral valve surgery for at least one year, without an effect on outcomes 21.

Kusunose et al. 22 studied 196 patients with moderate to severe, primary asymptomatic mitral regurgitation and showed that resting left ventricular strain, exercise TAPSE and exercise systolic pulmonary arterial pressure are independent predictors of time to surgery. Exercise- induced right ventricular dysfunction is an independent predictor of worse outcomes in in this patient cohort.

References- American Heart Association. About Arrhythmia. http://www.heart.org/HEARTORG/Conditions/Arrhythmia/AboutArrhythmia/About-Arrhythmia_UCM_002010_Article.jsp

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Division of Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities. Congenital Heart Defects (CHDs). https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/heartdefects/index.html

- Nishimura RA, Otto CM, et al. 2014 AHA/ ACC guideline for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: A report of the American College of Cardiology/ American Heart Association Task Force on practice guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(22):2438–2488.

- Apostolidou E, Maslow AD, Poppas A. Primary mitral valve regurgitation: Update and review. Glob Cardiol Sci Pract. 2017;2017(1):e201703. Published 2017 Mar 31. doi:10.21542/gcsp.2017.3 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6516795

- Horstkotte D, Loogen F, et al. The influence of heart valve replacement on the natural history of isolated mitral, aortic and multivalvular disease. Z Cardiol. 1983;72:494–503.

- Rosen SE, Borer JS, et al. Natural history of the asymptomatic/minimally symptomatic patient with severe mitral regurgitation secondary to mitral valve prolapse and normal right and left ventricular performance. Am J Cardiol. 1994;74:374–380.

- Ling L, Enriquez-Sarano M, et al. Clinical outcome of mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflets. N Eng J Med. 1996;335:1417–1423.

- Ling L, Enriquez-Sarano M, et al. Early surgery in patients with mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflets: A long- term outcome study. Circulation. 1997;96:1819–1825.

- Rosenhek R, Rader F, et al. Outcome of watchful waiting in asymptomatic severe mitral regurgitation. Circulation. 2006;113:2238–2244.

- Enriquez-Sarano M, Avierinos JF, et al. Quantitative determinants of the outcome of asymptomatic mitral regurgitation. N Eng J Med. 2005;352:875–883.

- Tribouilloy C, Grigioni F, et al. Survival implication of left ventricular end-systolic diameter in mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflet: A long-term follow-up multicenter study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54:1961–1968.

- Tourneau T, Messika-Zeitiun D, et al. Impact of left atrial volume on clinical outcome in organic mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:570–578.

- Barbieri A, Bursi F, et al. Prognostic and therapeutic implications of pulmonary hypertension complicating degenerative mitral regurgitation due to flail leaflet: A multicenter long- term international study. Eur Heart J. 2011;32(6):751–759.

- Eguchi K, Ohtaki E, et al. Pre- operative atrial fibrillation as the key determinant of outcome of mitral valve repair for degenerative mitral regurgitation. Eur Heart J. 2005;26(18):1866–1872.

- Magne J, Mahjoub H, et al. Prognostic importance of brain natriuretic peptide and left ventricular longitudinal strain in asymptomatic degenerative mitral regurgitation. Heart. 2012;98:584–591.

- Magne J, Lancelotti P, et al. Exercise- induced changes in degenerative mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:300–309.

- Button TM, Stewart RA, et al. Plasma natriuretic peptide level increase with symptoms and severity of mitral regurgitation. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2003;41:2280–2287.

- Detaint D, Messika-Zeitoun D, et al. B- type natriuretic peptide in organic mitral regurgitation: Determinants and impact on outcome. Circulation. 2005;111(18):2391–2397.

- Alashi A, Mentias A, et al. Synergistic utility of brain natriuretic peptide and left ventricular global longitudinal strain in asymptomatic patients with significant primary mitral regurgitation and preserved systolic function undergoing mitral valve surgery. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9:e004451

- Naji P, Griffin B, et al. Predictors of long- term outcomes in patients with significant myxomatous mitral regurgitation undergoing exercise echocardiography. Circulation. 2014a;129(12):1310–1319.

- Naji P, Griffin B, et al. Importance of exercise capacity in predicting outcomes and determining optimal timing of surgery in significant primary mitral regurgitation. J Am Heart Assoc. 2014b;3(5):e001010

- Kusunose K, Popovic Z, et al. Prognostic significance of exercise-induced right ventricular dysfunction in asymptomatic degenerative mitral regurgitation. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6:167–176.