Birth injuries

Birth injuries also called birth traumas are physical injuries experienced during childbirth and can affect either the mother or the baby. In newborn babies, a birth injury often called ‘neonatal birth trauma’ can include many things, from bruising to a broken bone. In mothers, birth injuries range from tearing in the vaginal area to damage to the pelvic floor. The National Vital Statistics Report defines birth injury as “an impairment of the neonate’s body function or structure due to an adverse event that occurred at birth” 1.

Birth injuries include a wide range of minor to major injuries that may occur due to various mechanical forces during labor and delivery. Birth injuries are different from birth defects or malformations and are often easily distinguishable from congenital defects by a focused clinical assessment. Birth trauma rates have steadily declined over the last few decades due to refinements in obstetrical techniques and the increased use of cesarean delivery in cases of dystocia or difficult vaginal deliveries. The birth trauma rate fell from 2.6 per 1000 live births in 2004 to 1.9 per 1000 live births in 2012. The rates of instrumental deliveries have also gradually declined over the past three decades with a reduction in the number of both forceps and vacuum-assisted deliveries 2.

The risk factors associated with birth injury can group into those related to the fetus, pregnancy, mother or iatrogenic factors (use of instrumentation during delivery) 3. Fetal and pregnancy-related factors include macrosomia (estimated fetal weight greater than 4000g), macrocephaly, very low birth weight, extreme prematurity, fetal congenital anomalies, oligohydramnios and malpresentations including breech presentation as well as other abnormal presentations (such as the face, brow, or transverse). Maternal factors may include maternal obesity, maternal diabetes, cephalopelvic disproportion, small maternal stature, primiparity, dystocia, difficult extraction, use of vacuum or forceps, prolonged or rapid labor 4.

The clinical management and prognosis of infants with birth injuries vary widely depending on the type and severity of the injury. The common sites for birth trauma can include the head, neck, and shoulders. Other less common locations include the face, abdomen, and lower limbs. A summary of the common traumatic clinical conditions occurring related to birth is listed below.

The following are common birth injuries:

- Swelling or bruising of the head

- Bleeding underneath one of the cranial bones.

- Breakage of small blood vessels in the eyes of a baby

- Facial nerve injury caused by pressure on the baby’s face

- Injury to the group of nerves that supplies the arms and hands

- Fracture of the clavicle or collarbone

Skeletal injuries

Most of the fractures resulting from birth trauma are associated with difficult extractions or abnormal presentations. Clavicular fractures are the most common bone fracture during delivery and can occur in up to 15 per 1000 live births. The clinical presentation is significant for crepitus at the site of fracture, tenderness and decreased movement of the affected arm with an asymmetric Moro reflex. Clavicular fractures have a good prognosis with spontaneous healing occurring in the majority of infants. The humerus is the most common long bone to fracture during birth, and this can be associated with a brachial plexus injury. The clinical presentation could be similar to a clavicular fracture with an asymmetric Moro reflex, inability to move the affected arm. Also, a significant deformity might be noted on the affected arm with swelling and tenderness at the site of the fracture. Rare conditions may involve a distal humeral epiphyseal separation due to birth trauma requiring expert orthopedic intervention 5. In general, immobilization for 3 to 4 weeks is necessary and often heals well without deformities. Other fractures such as femur fracture, rib fractures can occur during birth but are rare 6. On the other hand, femur fractures are extremely rare in newborns and may be seen in difficult vaginal breech extraction deliveries. Diagnosis is made by clinical exam with tenderness, swelling, and deformity of the thigh and confirmed further on plain radiographs. Orthopedic consultation is the recommendation for long bone fractures for appropriate immobilization.

What causes birth injury?

A difficult birth or injury to the baby can occur because of the baby’s size or the position of the baby during labor and delivery. Conditions that may be linked to a difficult birth include:

- Large babies. Birthweight over about 8 pounds, 13 ounces (4,000 grams).

- Abnormal birthing presentation. The baby is not head-first in the birth canal

- The baby is born prematurely or too early. Babies born before 37 weeks (premature babies have more fragile bodies and may be more easily injured).

- Cephalopelvic disproportion. The size and shape of the mother’s pelvis or birth canal is not adequate for the baby to be born vaginally.

- Labor is difficult or very long. An example of this is when contractions aren’t strong enough to move the baby through the birth canal.

- The mother is very overweight

- There is a Cesarean delivery

- Devices, like vacuum or forceps, are used to deliver the baby

Treating birth injury in babies

Most birth injuries in babies are temporary. If the injury was to the soft tissue, then no treatment is normally needed — the medical team will just monitor the baby and may run tests to check for other injuries.

If there has been a fracture, your baby may need an x-ray or other imaging. The limb may need to be immobilised and some babies may need surgery.

If your baby has damaged nerves, the medical team will monitor them closely and recovery can take a few weeks. For more serious nerve damage, your baby may need special care.

Shoulder dystocia birth

Shoulder dystocia is a birth injury that happens when one or both of a baby’s shoulders get stuck inside the mother’s pelvis during labor and birth. In most cases of shoulder dystocia, babies are born safely. But it can cause serious problems for both mom and baby. Dystocia means a slow or difficult labor or birth.

It’s often hard for health care providers to predict or prevent shoulder dystocia. They often discover it only after labor starts. Shoulder dystocia happens in 0.2 to 3 percent of pregnancies.

Shoulder dystocia key points

- Shoulder dystocia is a birth injury that happens when one or both of a baby’s shoulders get stuck inside the mother’s pelvis during labor.

- In most cases of shoulder dystocia, babies are born safely. But it can cause problems for both mom and baby.

- It’s often hard for health care providers to predict or prevent shoulder dystocia.

- When shoulder dystocia happens, your provider tries to move your body and your baby into a better position to help get your baby out.

- If your doctor recommends a scheduled C-section (cesarean section), ask if you can wait until at least 39 weeks to give your baby time to develop before birth.

Who is at risk for shoulder dystocia?

Shoulder dystocia can happen to any woman. Scientists do know that some things may make you more likely than others to have shoulder dystocia. These are called risk factors. A risk factor is something that makes you at risk for a condition. Having a risk factor doesn’t mean for sure that you’ll have shoulder dystocia. And risk factors for shoulder dystocia don’t seem to be helpful in predicting if you’ll have it. It’s hard for providers to predict or prevent.

Risk factors for shoulder dystocia include:

- Macrosomia. This is when your baby weighs more than 8 pounds, 13 ounces (4,000 grams) at birth. If your baby is this large, you may need to have a cesarean birth (also called c-section). This is surgery in which your baby is born through a cut that a doctor makes in your belly and uterus (womb). Most babies with macrosomia who are born vaginally (through the vagina) don’t have shoulder dystocia. In most cases of shoulder dystocia, the baby’s weight is normal.

- Having preexisting diabetes or gestational diabetes. Diabetes is a medical condition in which your body has too much sugar (called glucose or blood sugar) in your blood. This can damage organs in your body, including blood vessels, nerves, eyes and kidneys. Preexisting diabetes is when you have diabetes before you get pregnant. Gestational diabetes is a kind of diabetes some women get during pregnancy. Diabetes is a risk factor for having a large baby.

- Having shoulder dystocia in a previous pregnancy

- Being pregnant twins, triples or other multiples

- Being overweight or gaining too much weight during pregnancy

Conditions that are part of labor and birth also are risk factors for shoulder dystocia. These include:

- Getting a medicine called oxytocin to induce your labor (make your labor start).

- Getting an epidural to help with pain during labor. An epidural is pain medicine you get through a tube in your lower back that helps numb your lower body during labor. It’s the most common kind of pain relief used during labor.

- Having a very short or very long second stage of labor. This is the part of labor where you push and give birth.

- Having an assisted vaginal birth (also called operative vaginal birth). This means that your provider uses tools, like forceps or a vacuum, to help your baby through the birth canal. Forceps look like big tongs. Your provider places them around your baby’s head in the vagina to help guide your baby out. A vacuum is a suction cup that goes around your baby’s head in the vagina to help guide your baby out. This is the most common risk factor for shoulder dystocia.

What problems can shoulder dystocia cause?

Most moms and babies recover well from problems caused by shoulder dystocia.

Problems for the baby can include:

- Fractures to the baby’s clavicle (collarbone) and arm

- Damage to the brachial plexus nerves. These nerves go from the spinal cord in the neck down the arm. They provide feeling and movement in the shoulder, arm and hand. Damage can cause weakness or paralysis in the arm or shoulder. Paralysis is when you can’t feel or move one or more parts of your body.

- Lack of oxygen to the body (also called asphyxia). In the most severe cases, this can cause brain injury or even death. This is rare.

Problems for the mother can include:

- Postpartum hemorrhage. This is heavy bleeding after giving birth.

- Serious tearing of the perineum (the area between the vagina and the rectum). Surgery may be needed to repair the tearing.

- Uterine rupture. This is when the uterus tears during labor. This is rare.

Shoulder dystocia treatment

If your doctor thinks you may be at risk for shoulder dystocia, she can prepare you ahead of time for what to expect during labor and birth. And she can make sure staff and equipment are ready at the hospital.

If your doctor thinks your baby is large or if you have diabetes, your doctor may recommend scheduling a C-section. If so, ask about waiting until at least 39 weeks of pregnancy to have your baby. This gives your baby the time she needs to grow and develop before birth. Scheduling a c-section should be for medical reasons only. Your doctor may want to schedule a C-section if:

- She thinks your baby weighs at least 5,000 grams (about 11 pounds).

- You have diabetes and she thinks your baby weighs at least 4,500 grams (9 pounds, 15 ounces).

If you have shoulder dystocia, your doctor can try several methods to move you and your baby into better positions to open your pelvis wider and move your baby’s shoulders. Your doctor may:

- Press your thighs up against your belly. This is called the McRoberts maneuver.

- Press on your lower belly just above your pubic bone. This is called suprapubic pressure.

- Help your baby’s arm out of the birth canal

- Reach up into the vagina to try to turn your baby. Or turn you over so you’re on all fours (on your hands and knees).

- Give you an episiotomy. This is not done routinely but only in cases in which a larger opening to the vagina is helpful and the incision won’t affect the baby.

- Do a C-section, other surgical procedures or break your baby’s collarbone to release his shoulders. These are done only in severe cases of shoulder dystocia that aren’t resolved by other methods.

Newborn broken clavicle

Fractured clavicle newborn is the most frequently observed bone fracture as birth trauma and it is usually unilateral. Newborn broken clavicle is seen following shoulder dystocia deliveries or breech presentation of macrosomic newborns 7. The clavicle is the most frequently fractured bone as birth trauma. Most clavicular fractures are of the greenstick type, but occasionally the fracture is complete. The major causes of clavicular fractures are shoulder dystocia deliveries in vertex presentations and extended arms in breech deliveries 8. It is usually associated with vigorous, forceful manipulation of the arm and shoulder. However, fracture of the clavicle may also occur in infants following normal delivery 9. It has been suggested that some fetuses may be more vulnerable to spontaneous birth trauma secondary to abnormal forces of labor, maternal pelvic anatomy and in utero fetal position 10. Neonatal clavicle fractures are usually observed in unilateral whereas bilateral clavicle fractures are extremely rare. Because of its rarity we present two neonates with bilateral clavicle fracture.

The clavicle almost always heals with no problems. Clavicle fractures heal quickly on their own without treatment. Your doctor may recommend keeping your baby’s arm and shoulder still for several days. If so, this is done by putting the infant’s arm in a sling or pinning the infant’s sleeve to their shirt.

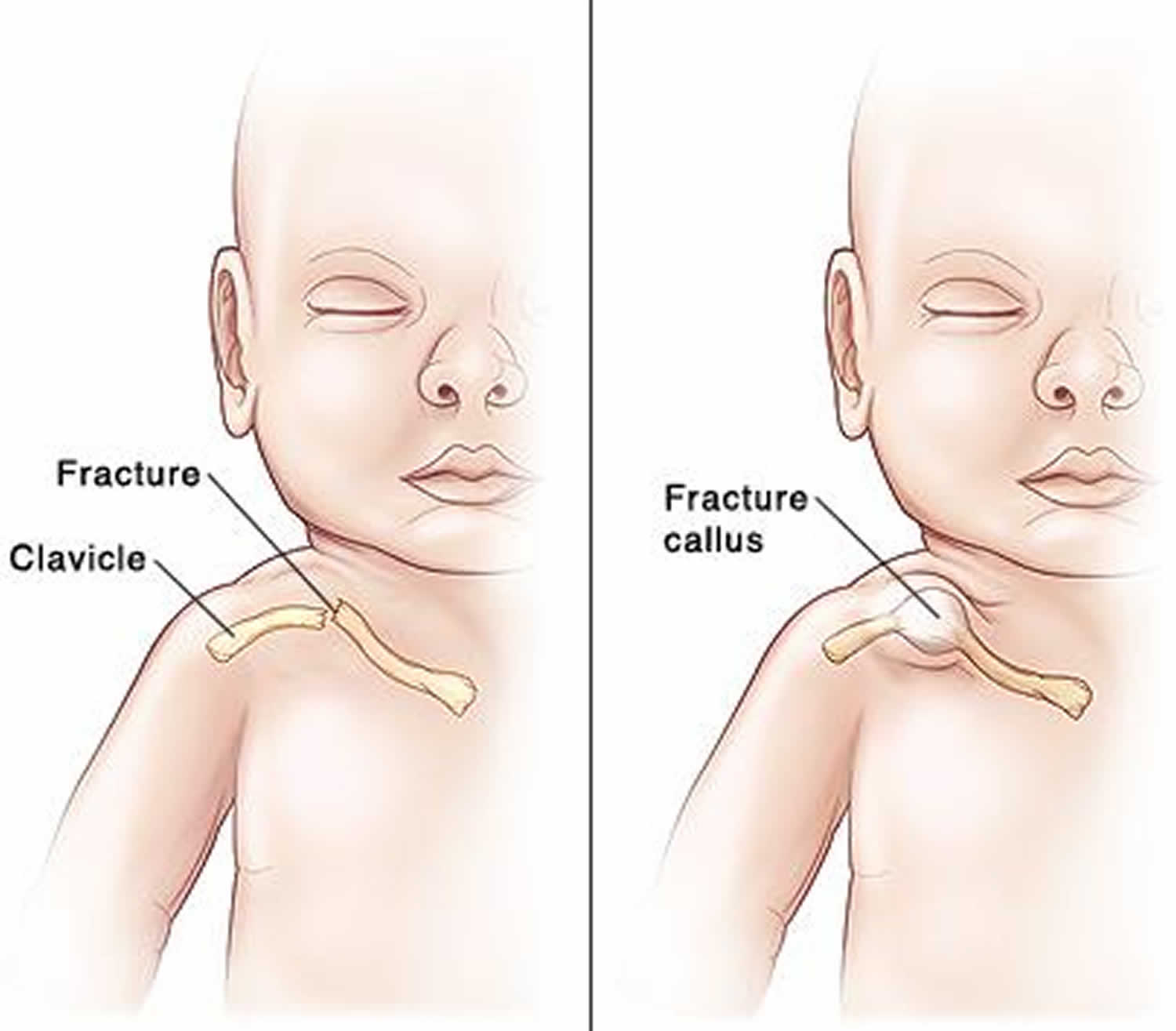

Figure 1. Fractured clavicle newborn

What are the long-term concerns for newborn broken clavicle?

Even for serious collarbone fractures, healing is usually excellent with no long-term problems. A bump may remain on the collarbone over the area of the break. This bump will slowly go away over time.

Newborn broken clavicle symptoms

The baby will not move the painful, injured arm. Instead, the baby will hold it still against the side of the body. Lifting the baby under the arms causes the child pain. Sometimes, the fracture can be felt with the fingers, but the problem often can’t be seen or felt.

Signs of a fractured clavicle in newborn:

- Your baby may hold the arm bent in front of the chest and not move it. This is called “pseudo paralysis.” The arm is not paralyzed. But moving the arm may be painful, so the baby avoids moving it.

- The broken area of the collarbone may move when pressed on, and may feel like it is “crunching.”

- A bump may be seen on the collarbone. This is called a fracture callus and is a sign that the fracture is healing.

Within a few weeks, a hard lump may develop where the bone is healing. This lump may be the only sign that the newborn had a broken collar bone.

Newborn broken clavicle diagnosis

The fracture may be found when the baby is examined soon after birth. An X-ray may be done to confirm the fracture. In some cases, the break is so mild that it is not diagnosed until the fracture callus begins to form and a bump is noticed at the collarbone.

Newborn broken clavicle treatment

Generally, there is no treatment other than lifting the child gently to prevent discomfort. Occasionally, the arm on the affected side may be immobilized, most often by simply pinning the sleeve to the clothes.

Newborn broken clavicle prognosis

Full recovery occurs without treatment.

Hematoma on newborn head

Hematoma on newborn head refer to a group of extracranial injuries that occur during delivery and are secondary to edema (swelling) or bleeding into the varying locations within the scalp and skull. Bleeding outside of the skull bones can lead to an accumulation of blood either above or below the thick fibrous covering (periosteum) of one of the skull bones.

- Swelling and bruising of the scalp is common but not serious and generally resolves within a few days.

- Scalp scratches can occur when instruments (such as monitor leads attached to the scalp, forceps, or vacuum extractors) are used during a vaginal delivery.

- A cephalhematoma is blood accumulation below the periosteum. Cephalohematomas feel soft and can increase in size after birth. Cephalohematomas disappear on their own over weeks to months and almost never require any treatment. However, they should be evaluated by the pediatrician if they become red or start to drain liquid.

- A subgaleal hemorrhage is bleeding directly under the scalp above the periosteum covering the skull bones. Blood in this area can spread and is not confined to one area like a cephalohematoma. It can cause significant blood loss and shock, which may even require a blood transfusion. A subgaleal hemorrhage may result from the use of forceps or a vacuum extractor, or may result from a blood clotting problem.

- Fracture of one of the bones of the skull may occur before or during the birth process. Unless the skull fracture forms an indentation (depressed fracture), it generally heals rapidly without treatment.

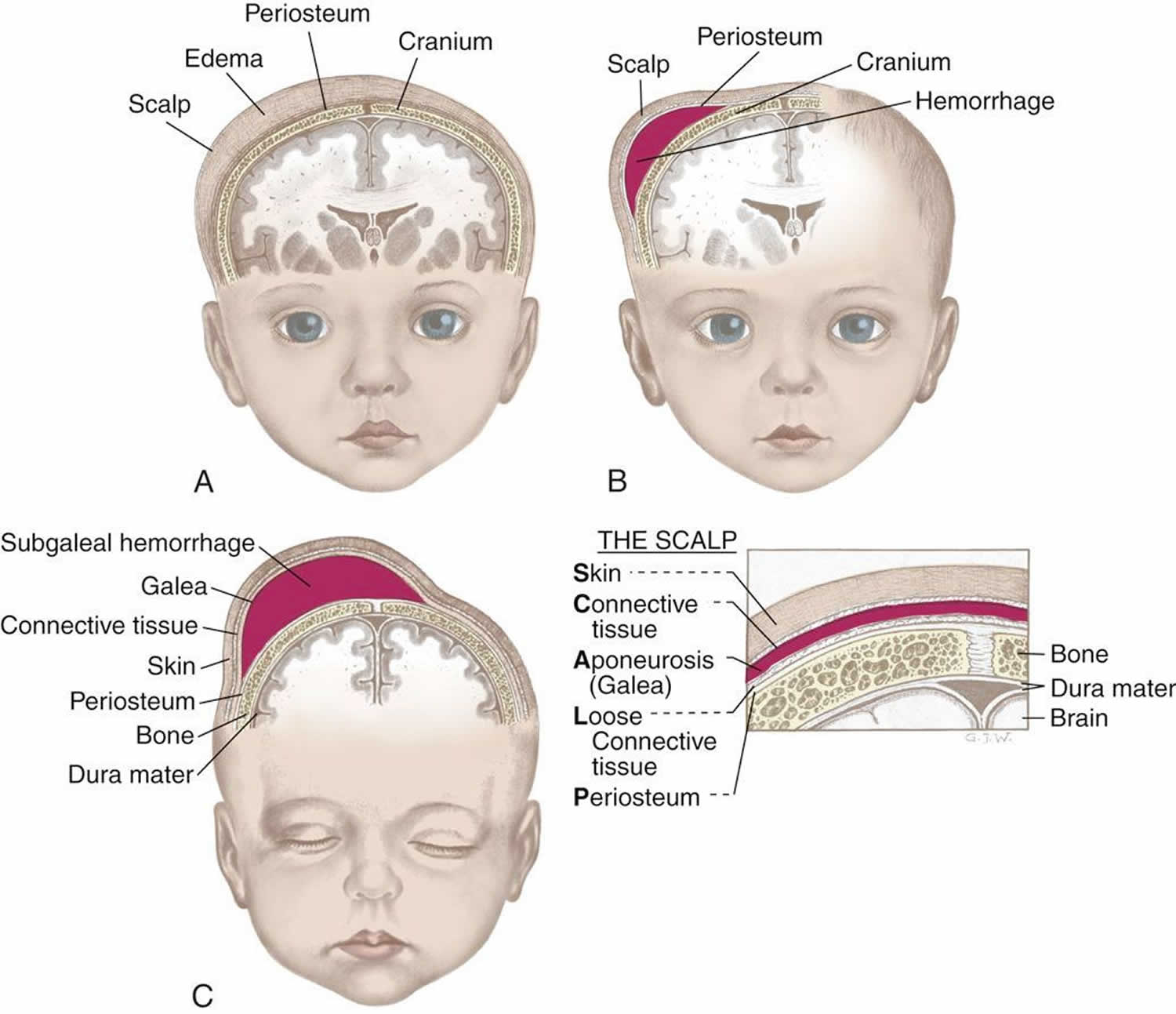

Figure 2. Hematoma on newborn head

Footnotes: (A) Caput succedaneum, (B) Cephalhematoma, (C) Subgaleal hemorrhage

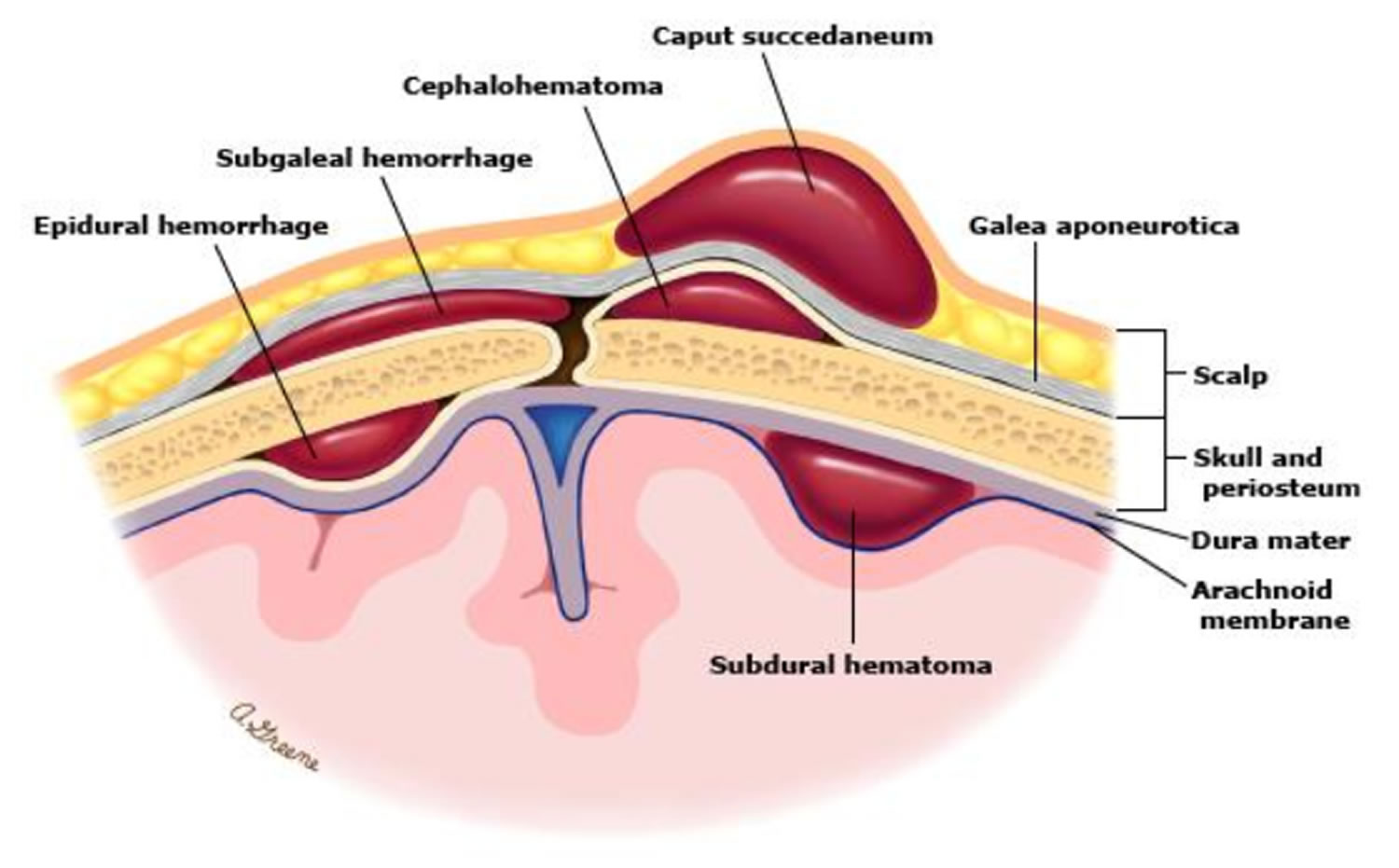

Figure 3. Extracranial haemorrhage in a newborn

Caput succedaneum

Caput succedaneum is swelling of the scalp in a newborn. It is most often brought on by pressure from the uterus or vaginal wall during a head-first (vertex) delivery. The edema in caput succedaneum crosses the suture lines. It may involve wide areas of the head or it may just be a size of a large egg. A caput succedaneum may be detected by prenatal ultrasound, even before labor or delivery begins. It has been found as early as 31 weeks of pregnancy. Very often, this is due to an early rupture of the membranes or too little amniotic fluid. It is less likely that a caput will form if the membranes stay intact.

A caput succedaneum is more likely to form during a long or hard delivery. It is more common after the membranes have broken. This is because the fluid in the amniotic sac is no longer providing a cushion for the baby’s head. Vacuum extraction done during a difficult birth can also increase the chances of a caput succedaneum.

Caput succedaneum causes

- Mechanical trauma of the initial portion of scalp pushing through a narrowed cervix

- Prolonged or difficult delivery

- Vacuum extraction

The pressure on baby’s head at birth interferes with blood flow from the area causing a localized edema. The edematous area crosses the suture lines and is soft. Caput Succedaneum also occurs when a vacuum extractor is used. In this case, the Caput Succedaneum corresponds to the area where the extractor is used to hasten the second stage of labor.

Caput succedaneum symptoms

Caput succedaneum symptoms may include:

- Soft, puffy swelling on the scalp of a newborn infant (edematous region above the periosteum that crosses suture lines)

- Visualize pitting edema on physical exam

- Presents at birth, typically after prolonged or difficult labor due to compression against bony prominence of maternal pelvis

- Possible bruising or color change on the scalp swelling area

- Swelling that may extend to both sides of the scalp

- Swelling that is most often seen on the portion of the head which presented first

- Usually resolves within a few days and requires no further treatment

Caput succedaneum possible complications

Complications may include a yellow color to the skin (jaundice) if bruising is involved.

Complications to look out for include long term scarring and alopecia. Halo scalp ring is an alopecic ring that can develop after resolution

Caput succedaneum diagnosis

Your health care provider will look at the swelling to confirm that it is a caput succedaneum. No other testing is needed.

Caput succedaneum treatment

No treatment is needed. The problem most often goes away on its own within a few days.

Caput succedaneum prognosis

Complete recovery can be expected. The scalp will go back to a normal shape.

Cephalohematoma

A cephalohematoma is a collection of blood between the periosteum of a skull bone and the bone itself that has seeped under the outer covering membrane of one of the skull bones. The swelling with cephalohematoma is not present at birth rather it develops within the first 24 to 48 hours after birth. Cephalohematoma occurs in one or both sides of the head. Cephalohematoma occasionally forms over the occipital bone. This is usually caused during birth by the pressure of the head against the mother’s pelvic bones. The lump is confined to one side of the top of the baby’s head and, in contrast to caput succedaneum, may take a week or two to disappear. The breakdown of the blood collected in a cephalohematoma may cause these infants to become somewhat more jaundiced than others during the first week of life.

Cephalohematoma key points:

- Subperiosteal bleed due to rupture of vessels beneath the periosteum

- Presents within the first 24 to 48 hours after birth as swelling that does NOT cross suture lines

- Can have some discoloration

- More common when forceps or vacuum delivery is performed

- Usually doesn’t expand after delivery

- If one notices expansion pursue imaging and work up for source of continuing bleed

- Resolves spontaneously over course of a few weeks

- May cause indirect hyperbilirubinemia due to absorption of the bleed

- Monitor for calcification and ossification, which can result in deformity of skull

- If the cephalohematoma becomes erythematous and fluctuant, infection might be present. Most commonly due to E. coli infection. Must do incision and drainage of abscess and debridement of necrotic skull if needed

Cephalohematoma causes

- Rupture of a periostal capillary due to the pressure of birth

- Instrumental delivery

Cephalohematoma signs and symptoms

Swelling of the infant’s head 24-48 hours after birth

Discoloration of the swollen site due to presence of coagulated blood

Has clear edges that end at the suture lines

Cephalohematoma treatment

- Observation and support of the affected part.

- Transfusion and phototherapy may be necessary if blood accumulation is significant

Subgaleal hematoma newborn

Subgaleal hemorrhage is bleeding or an accumulation of blood in the loose connective tissue of the subgaleal space (the loose areolar tissue space between the galea aponeurotica and the periosteum of the skull), directly under the scalp above the periosteum covering the skull bones. Blood in this area can spread and is not confined to one area like a cephalohematoma. It can cause significant blood loss and shock, which may even require a blood transfusion. A subgaleal hemorrhage may result from the use of forceps or a vacuum extractor, or may result from a blood clotting problem. Subgaleal hemorrhage is associated with 12-25% mortality due to potential of hypovolemic shock with 20-40% neonatal blood volume shifting into subgaleal space.

Tractional and rotational forces with the use of vacuum extraction can result in rupture of veins and hemorrhage into different layers of the scalp. Most significantly, subgaleal hemorrhage may result from rupture of emissary veins into the subgaleal space. May be associated with perinatal hypoxia.

Subgaleal hemorrhage injury occurs when there is traction pulling the scalp away from the stationary bony calvarium, resulting in the shearing or severing of the bridging vessels. A difficult vaginal delivery resulting in the use of forceps or vacuum is the most common predisposing event in the formation of subgaleal hemorrhage. It has been estimated to occur in 1 in 2500 spontaneous vaginal deliveries without the use of vacuum or forceps and 59 of 10,000 vacuum-assisted deliveries 11. Since the subgaleal space is a significant potential space extending over the entire area of the scalp from the anterior attachment of the galea aponeurosis near the frontal bones to the posterior attachment at the nape of the neck, there is a potential for massive bleeding into this space that could result in acute hypovolemic shock, multi-organ failure, and death. Treatment includes supportive care with early recognition and restoration of blood volume using blood or fresh frozen plasma to correct the acute onset hypovolemia. The hemorrhage itself is not drained and allowed to resorb over time. A workup for bleeding disorders may be considered in selected cases if the degree of bleeding is out of proportion to the trauma at birth.

Subgaleal hemorrhage key points:

- Subgaleal hemorrhage bleed located between periosteum of skull and the aponeurosis

- Presents as fluctuant swelling of the head that may shift with movement

- Rapid loss of intravascular volume causes tachycardia and pallor

- Potential for loss of 20-40 percent of neonate’s blood volume

- Most are due to vacuum-assisted delivery, so monitor for following those deliveries

- Develops around 12-72 hours after delivery

- Early recognition is most important for survival

- Once suspected, monitor by serial measurements of hematocrit and frontal circumference

- Volume resuscitation with packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, and normal saline to stabilize vitals

- May need surgical evacuation

Subgaleal hemorrhage causes

- Vacuum extraction: Subgaleal hemorrhage is often preceded by a difficult vacuum extraction with either incorrect positioning of the cup, prolonged extraction time (>20 minutes), >3 pulls or >2 cup detachments or failed vacuum extraction. Boo and colleagues 12 also showed that nulliparity, 5 minute Apgar score < 8, cup marks on the sagittal suture, leading edge of cup <3 cm from anterior fontanelle or failed vacuum extraction were significant risk factors for subgaleal hemorrhage.

Other risk factors

- Maternal factors: Premature rupture of membranes (PROM) >12 hours,maternal exhaustion and prolonged second stage, previous high or mid cavity forceps delivery.

- Neonatal factors: Macrosomia, neonatal coagulopathy (vitamin K deficiency, Factor VIII deficiency, FactorIX deficiency), low birthweight, male sex (2:1 to 8:1), low Apgar scores (< 8 at 5 minutes), need for resuscitation at birth and cord blood acidosis, fetal malpresentation.

Subgaleal hemorrhage signs and symptoms

Local signs

- Early recognition in crucial for survival.Combination of inspection and palpation to confirm subgaleal hemorrhage.

- Diffuse, fluctuant swelling of head which may shift with movement. Palpation of the scalp has been described as a leather pouch filled with fluid.

- As the hemorrhage extends, elevation and displacement of the ear lobes and peri orbital oedema (puffy eyelids) can be observed.

- Irritability and pain on handling will be noted.

- Days later bruising appears behind the ears and or the eyelids.

Systemic signs:

- Signs consistent with hypovolemic shock: tachycardia, tachypnoea, dropping hematocrit on blood gases, increasing lactates or worsening acidosis, poor activity, pallor, hypotension and acidosis. Neurological dysfunction and seizures are a late sign.Ischemic end organ damage to liver or kidneys can manifest as worsening liver and renal function and this is a poor prognostic indicator.

- 6% of subgaleal hemorrhage cases are asymptomatic, 15-20% are mild, 40-50% are moderate and 25-33% are severe.

- Profound shock can occur rapidly with blood loss.

Subgaleal hemorrhage treatment

Initial Action: In the Delivery Suite and Postnatal Wards

- Administer intramuscular vitamin K as soon as possible.

- Level 1 surveillance (minimum for all infants delivered by instrumental delivery)

- Baseline observations (activity, color, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure and head circumference) at one hour.

- Avoid hats/ bonnets (or remove frequently) to note head shape (increase in head circumference by 1cm may suggest 40mL blood seepage into subgaleal space).

- Clinical concerns (to increase observation frequency/ escalate to Level 2 surveillance).

- Level 2 surveillance (Indicated: if vacuum extraction time total >20 minutes and/or > 3 pulls and/or > 2 cup detachments, clinical concerns from level 1 surveillance, at clinician’s request)

- Take cord blood (acid base status, pH, and lactate).

- Hematocrit / complete blood count (CBC) and platelet count.

- Hourly observations for first 2hrs, then 2hrly for next 6hrs. Can extend observations for at least first 12-24 hours, consider saturation monitoring.

- Document activity, color, heart rate, respiratory rate, blood pressure, head size and shape, location and nature of swelling.

- Level 3 surveillance (Indications: clinical suspicion of subgaleal hemorrhage immediately following delivery, clinical concerns on Level 2 surveillance)

- Urgent review by paediatric senior registrar or consultant paediatrician. If subgaleal hemorrhage confirmed, consider admission to special care nursery.

Immediate Investigations:

- Full blood picture and Coagulation profile: On admission and repeated at clinical team’s discretion. Up to 81% of neonates with subgaleal hemorrhage may develop coagulopathy.

- Group and blood cross match (notify blood bank).

- Venous/capillary gas including lactate and base excess, electrolytes (2-4 hourly).

- Maintain blood glucose level > 2.6 mmol/L.

In the Neonatal Nursery

The basis of effective management is aggressive resuscitation to restore blood volume, provide circulatory support, correction of acidosis and coagulopathy.

Above investigations to be carried out after insertion of a peripheral intravenous access, which should be left indwelling for 12 hours if baby remaining in nursery.

- Ongoing monitoring:

- Continuously monitor heart rate, respiration, oxygen saturation and blood pressure (non-invasively if no arterial line) at least for the first 24 hours.

- Continue to assess capillary refill and peripheral perfusion.

- Regularly observe and palpate scalp swelling to assess for continuing blood loss, change in head shape or head circumference (measure head circumference hourly for the first 6-8 hours of life), change in color, displacement of ears.

- Volume replacement: 20 mL/kg of normal saline, if severe hypovolemia, request for urgent O negative blood and fresh frozen plasma (FFP).

- Monitor urine output.

- Repeat CBC and coagulations studies, (4-6 hours after initial assessment).

- If coagulation studies are abnormal then correct with 20mLs/kg of Fresh Frozen Plasma. Consider giving Cryoprecipitate 5mLs/kg, if there is continued bleeding or the fibrinogen level are less than 1.5 g/l. Discuss with on call haematologist about the need for use of recombinant factor VIIa.

- If thrombocytopenic, consider platelet transfusion (if platelet count<50).

- Inotropes, vasopressors and multiple packed red cell transfusions may be required for severe cases of shock.

- Ongoing assessment for jaundice.

Recognition of Hypovolemia

Pointers to significant volume loss include:

- A high or increasing heart rate (> 160 bpm), low or falling hemoglobin or hematocrit, poor peripheral perfusion with slow capillary refill (>3 seconds), low or falling blood pressure (mean arterial blood pressure (MBP) < 40 mmHg in a term baby), presence of or worsening of a metabolic acidosis.

- Consideration of a functional bedside echocardiography (by the attending neonatologist) can be useful in assessment of volume status. Small systemic veins and low ventricular filling volumes can be pointers to hypovolemia

Consider elective intubation and ventilation for worsening shock.

- Look for concomitant injuries:

- Hypoxic ischaemic encephalopathy occurs in 62-72% of subgaleal hemorrhage. Brain trauma resulting in cerebral edema and/or intracranial hemorrhage occurs in 33-40%.

- Less common: subdural hematoma, duraltear with herniation, superior sagittal sinus rupture, pseudomeningocoeleand encephalocoele, and subconjunctival and retinal haemorrhage. Elevated intracranial pressure (ICP) from the subgaleal hemorrhage mass effect is reported. Skull fractures may be associated. Once stabilized, consider neuroimaging (cranial ultrasound or MRI).

Skull fractures

Skull fractures from birth trauma are most often a result of instrumented vaginal delivery. These fractures could be linear or depressed and are usually asymptomatic unless associated with an intracranial injury. Plain film radiographs of the skull usually clarify the diagnosis, but computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is the recommendation if there is suspicion of intracranial injury or presence of neurologic symptoms.

Intracranial hemorrhages

Traumatic intracranial hemorrhages include epidural, subdural, subarachnoid, intraventricular and less frequently intracerebral and intracerebellar hemorrhages.

- Epidural hemorrhage is very rare in neonates and usually accompanies linear skull fractures in the parietal-temporal region following an operative delivery. Signs include bulging fontanelle, bradycardia, hypertension, irritability, altered consciousness, hypotonia, seizures. Diagnosis is via CT or MRI of the head which shows a convex appearance of blood collection in the epidural space. Prompt neurosurgical intervention is necessary due to the potential to deteriorate rapidly.

- Subdural hemorrhage is the most common type of intracranial hemorrhage in neonates. Operative vaginal delivery is a major risk factor, and hemorrhage over the cerebral convexities is the most common site. Presenting signs/symptoms include bulging fontanelle, altered consciousness, irritability, respiratory depression, apnea, bradycardia, altered tone, and seizures. Subdural hemorrhages can occasionally be found incidentally in asymptomatic neonates. Management depends on the location and extent of the bleeding. Surgical evacuation is reserved for large hemorrhages causing raised intracranial pressure and associated clinical signs.

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage is the second most common type of neonatal intracranial hemorrhage and is usually the result of the rupture of bridging veins in the subarachnoid space. Operative vaginal delivery is a risk factor, and the infants are typically asymptomatic unless the hemorrhage is extensive. Ruptured vascular malformations are a rare cause of subarachnoid hemorrhages, even in the neonatal population. Treatment is usually conservative.

- Intraventricular hemorrhage even though most commonly seen in premature infants, can also occur in term infants depending on the nature and extent of the birth injury 13. Intracerebral and intracerebellar hemorrhages are less common and occur as a result of occipital diastasis.

Cranial nerve injuries

Facial nerve is the most common cranial nerve injured with a traumatic birth. It occurs in up to 10 per 1000 live births and is usually a result of pressure on the facial nerve by forceps or from a prominent maternal sacral promontory during descent. Clinical manifestations include diminished movement or loss of motion on the affected side of the face. Facial nerve palsy requires differentiation from asymmetric crying facies which results from congenital hypoplasia of the depressor anguli oris muscle and causes a localized movement abnormality of the corner of the mouth. Although forceps delivery has a strong association, facial palsy can occur in the newborn without apparent trauma 14. The prognosis in traumatic facial nerve injury is good with spontaneous resolution usually noted within the first few weeks of life.

Peripheral nerve and spinal cord injuries

Brachial plexus injuries

Brachial plexus injuries occur in up to 2.5 per 1000 live births and are the result of stretching of the cervical nerve roots during the process of delivery. Brachial plexus injuries are usually unilateral, and risk factors include macrosomia, shoulder dystocia, difficult delivery, breech position, multiparity and assisted deliveries 15.

- Injury involving the fifth and sixth cervical nerve roots results in Erbs-Duchenne palsy manifested by weakness in the upper arm. Adduction and internal rotation of the arm with flexion of the fingers are presenting symptoms; this is by far the most common form of brachial plexus injury.

- Injury to eighth cervical and first thoracic nerves results in Klumpke’s palsy manifested by paralysis of the muscles of the hand, absent grasp reflex and sensory impairment along the ulnar side of the forearm and arm.

- Injury to all the nerve roots can result in total arm paralysis.

- Injury to the phrenic nerve can be an associated feature of brachial palsy. Clinical manifestations include tachypnea with asymmetric chest motion and diminished breath sounds on the affected side.

The majority of brachial plexus injuries are stretch injuries, and treatment is conservative with physical therapy playing a major role in the return of gradual function 16. Rare, severe cases of brachial plexus injuries result in lasting weakness on the affected side.

Spinal cord injuries

Spinal cord injuries are infrequent in the neonatal period and are usually a result of excessive traction or rotation of the spinal cord during extraction 17. The clinical manifestations depend on the type and location of the lesion. Higher lesions (cervical/upper thoracic) are associated with a high mortality rate and lower lesions (lower thoracic, lumbosacral) may result in significant morbidity with bladder and bowel dysfunction. Diagnosis is via ultrasonography or MRI of the spinal cord. Management points towards presenting clinical symptomatology with cardiorespiratory stabilization as needed.

Facial injuries

Ocular injuries

Subconjunctival hemorrhages are superficial hematomas seen under the bulbar conjunctiva, commonly seen in infants born after going through labor. It is suggested to be due to ruptured subconjunctival capillaries from venous congestion, occurring from increased back pressure in the head and neck veins. This injury can result from either a nuchal cord or from increased abdominal or thoracic compression during uterine contractions 18. Subconjunctival hemorrhage is a benign condition in the newborn and resolves without intervention. A more significant ocular injury may occur with the use of instrumentation during delivery (forceps), resulting in corneal abrasions, vitreous hemorrhages, etc. that require immediate attention and referral to an ophthalmologist to prevent long term visual defects 19.

Soft tissue injuries

Soft tissue injuries occurring as a result of birth trauma include petechiae, bruising, ecchymoses, lacerations and subcutaneous fat necrosis. Subcutaneous fat necrosis is thought to be a result of ischemic injury to the adipose tissue and characterized by palpation of soft, indurated nodules in the subcutaneous plane. These lesions resolve gradually over the course of a few weeks. Hypercalcemia is one of the complications; therefore it is recommended to monitor serum calcium 20. There are reports of accidental lacerations during cesarean section deliveries, with an Italian study showing a 3% incidence of accidental lacerations during cesarean sections, and a higher incidence in emergent deliveries compared to scheduled cesarean deliveries 21.

Visceral injuries

Birth trauma resulting in abdominal visceral injuries is uncommon and primarily consists of hemorrhage into the liver, spleen or adrenal gland. The clinical presentation depends on the volume of blood loss and can include pallor, bluish discoloration of the abdomen, distension of the abdomen, and shock. Treatment is supportive with volume resuscitation and surgical intervention if needed.

References- Dumpa V, Kamity R. Birth Trauma. [Updated 2019 Dec 31]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK539831

- Merriam AA, Ananth CV, Wright JD, Siddiq Z, D’Alton ME, Friedman AM. Trends in operative vaginal delivery, 2005-2013: a population-based study. BJOG. 2017 Aug;124(9):1365-1372.

- Werner EF, Janevic TM, Illuzzi J, Funai EF, Savitz DA, Lipkind HS. Mode of delivery in nulliparous women and neonatal intracranial injury. Obstet Gynecol. 2011 Dec;118(6):1239-46.

- Vitner D, Hiersch L, Ashwal E, Nassie D, Yogev Y, Aviram A. Outcomes of vacuum-assisted vaginal deliveries of mothers with gestational diabetes mellitus. J. Matern. Fetal. Neonatal. Med. 2019 Nov;32(21):3595-3599.

- Patil MN, Palled E. Epihyseal Separation of Lower end Humerus in A Neonate-Diagnostic and Management Difficulty. J Orthop Case Rep. 2015 Oct-Dec;5(4):7-9.

- Basha A, Amarin Z, Abu-Hassan F. Birth-associated long-bone fractures. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2013 Nov;123(2):127-30.

- Kanik A, Sutcuoglu S, Aydinlioglu H, Erdemir A, Arun Ozer E. Bilateral clavicle fracture in two newborn infants. Iran J Pediatr. 2011;21(4):553‐555. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3446140

- Mangurten HH. Birth injuries. In: Martin RJ, Fanaroff AA, Walsh MC, editors. Fanaroff and Martin’s Neonatal and Perinatal Medicine. Disease of the fetuses and infant. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2006. pp. 529–59.

- Kaplan B, Rabinerson D, Avrech OM, et al. Fracture of the clavicle in the newborn following normal labor and delivery. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1998;63(1):15–20.

- Peleg D, Hasnin J, Shalev E. Fractured clavicle and Erb’s palsy unrelated to birth trauma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1997;177(5):1038–40.

- Plauché WC. Subgaleal hematoma. A complication of instrumental delivery. JAMA. 1980 Oct 03;244(14):1597-8.

- Boo NY, Foong KW, Mahsy ZA, Yong SC, Jaafar R. Risk factors associated with subaponeurotic haemorrhage in full term infants exposed to vacuum extraction. Br J Obstet Gynaecol, 2005: 112; 1516-21

- Hayden CK, Shattuck KE, Richardson CJ, Ahrendt DK, House R, Swischuk LE. Subependymal germinal matrix hemorrhage in full-term neonates. Pediatrics. 1985 Apr;75(4):714-8.

- Al Tawil K, Saleem N, Kadri H, Rifae MT, Tawakol H. Traumatic facial nerve palsy in newborns: is it always iatrogenic? Am J Perinatol. 2010 Oct;27(9):711-3.

- Borschel GH, Clarke HM. Obstetrical brachial plexus palsy. Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2009 Jul;124(1 Suppl):144e-155e.

- Alfonso DT. Causes of neonatal brachial plexus palsy. Bull NYU Hosp Jt Dis. 2011;69(1):11-6.

- Menticoglou SM, Perlman M, Manning FA. High cervical spinal cord injury in neonates delivered with forceps: report of 15 cases. Obstet Gynecol. 1995 Oct;86(4 Pt 1):589-94.

- Katzman GH. Pathophysiology of neonatal subconjunctival hemorrhage. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1992 Mar;31(3):149-52.

- McAnena L, O’Keefe M, Kirwan C, Murphy J. Forceps Delivery-Related Ophthalmic Injuries: A Case Series. J Pediatr Ophthalmol Strabismus. 2015 Nov-Dec;52(6):355-9.

- Del Pozzo-Magaña BR, Ho N. Subcutaneous Fat Necrosis of the Newborn: A 20-Year Retrospective Study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016 Nov;33(6):e353-e355.

- Dessole S, Cosmi E, Balata A, Uras L, Caserta D, Capobianco G, Ambrosini G. Accidental fetal lacerations during cesarean delivery: experience in an Italian level III university hospital. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2004 Nov;191(5):1673-7.