Bronchopulmonary sequestration

Bronchopulmonary sequestration also called accessory lung or pulmonary sequestration, is a rare congenital cystic piece of abnormal lung tissue that doesn’t function like normal lung tissue. It can form outside (extralobar) or inside (intralobar) the lungs, but is not connected directly to the airways. Bronchopulmonary sequestration consists of a nonfunctioning mass of lung tissue that lacks normal communication with the tracheobronchial tree and receives its arterial blood supply from the systemic circulation 1. The blood supply to bronchopulmonary sequestration is through aberrant vessels from systemic circulation, most commonly the descending thoracic aorta 2. The abnormal tissue can be microcystic, containing many small cysts, or macrocystic, containing several large cysts. The term sequestration is derived from the Latin verb sequestare, which means ‘to separate’ and it was first introduced as a medical term by Pryce in 1964 3. Bronchopulmonary sequestration is rare, representing about 1 to 6% of all congenital lung anomalies and may go undetected during the prenatal period and early childhood years 4. Some authors propose a greater male prevalence (this may be the case for the extralobar type) 5. The age of presentation is dependent on the type of bronchopulmonary sequestration. Nearly one-half of the adult patients diagnosed with bronchopulmonary sequestration manifested no relevant symptoms.

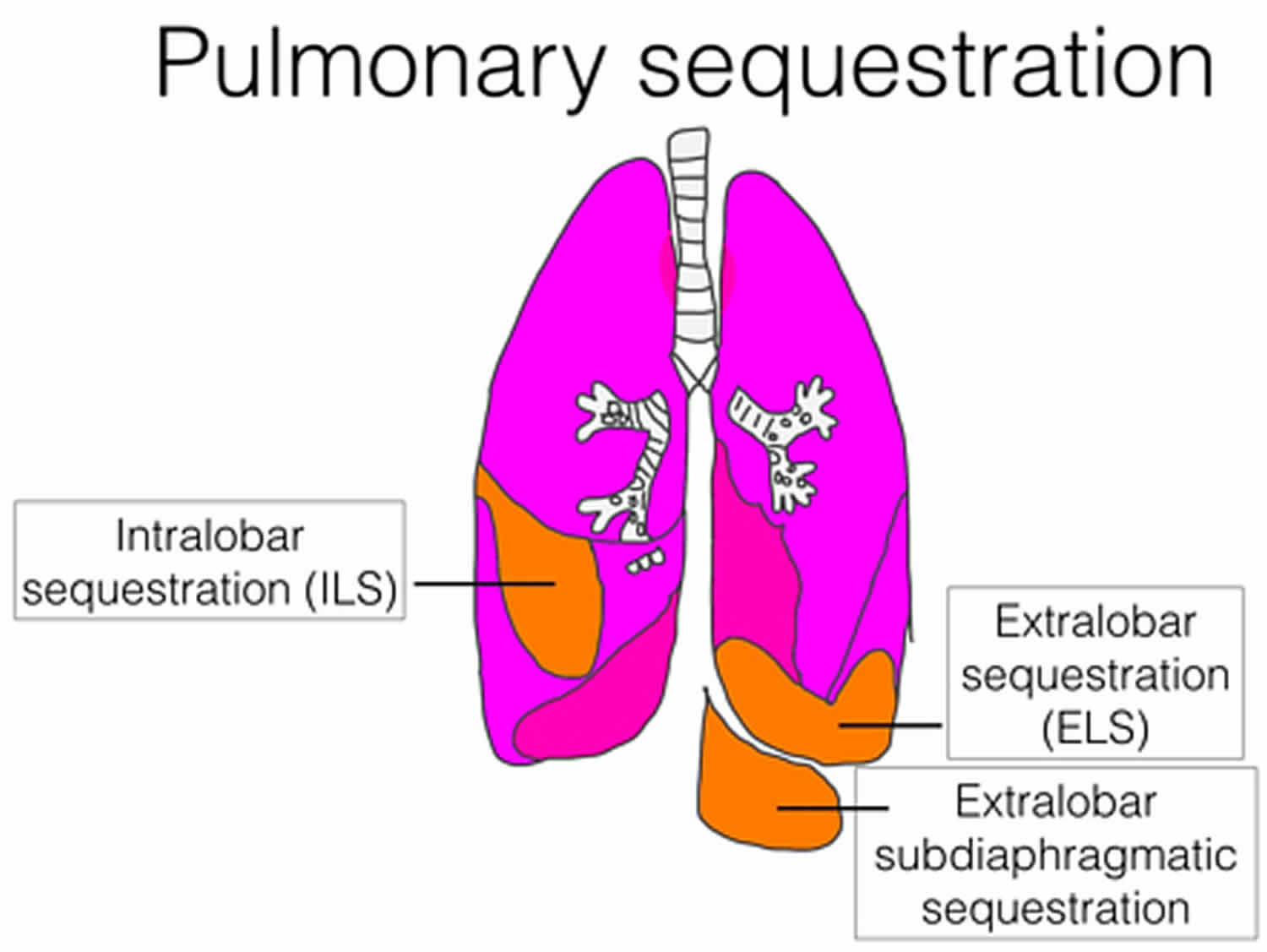

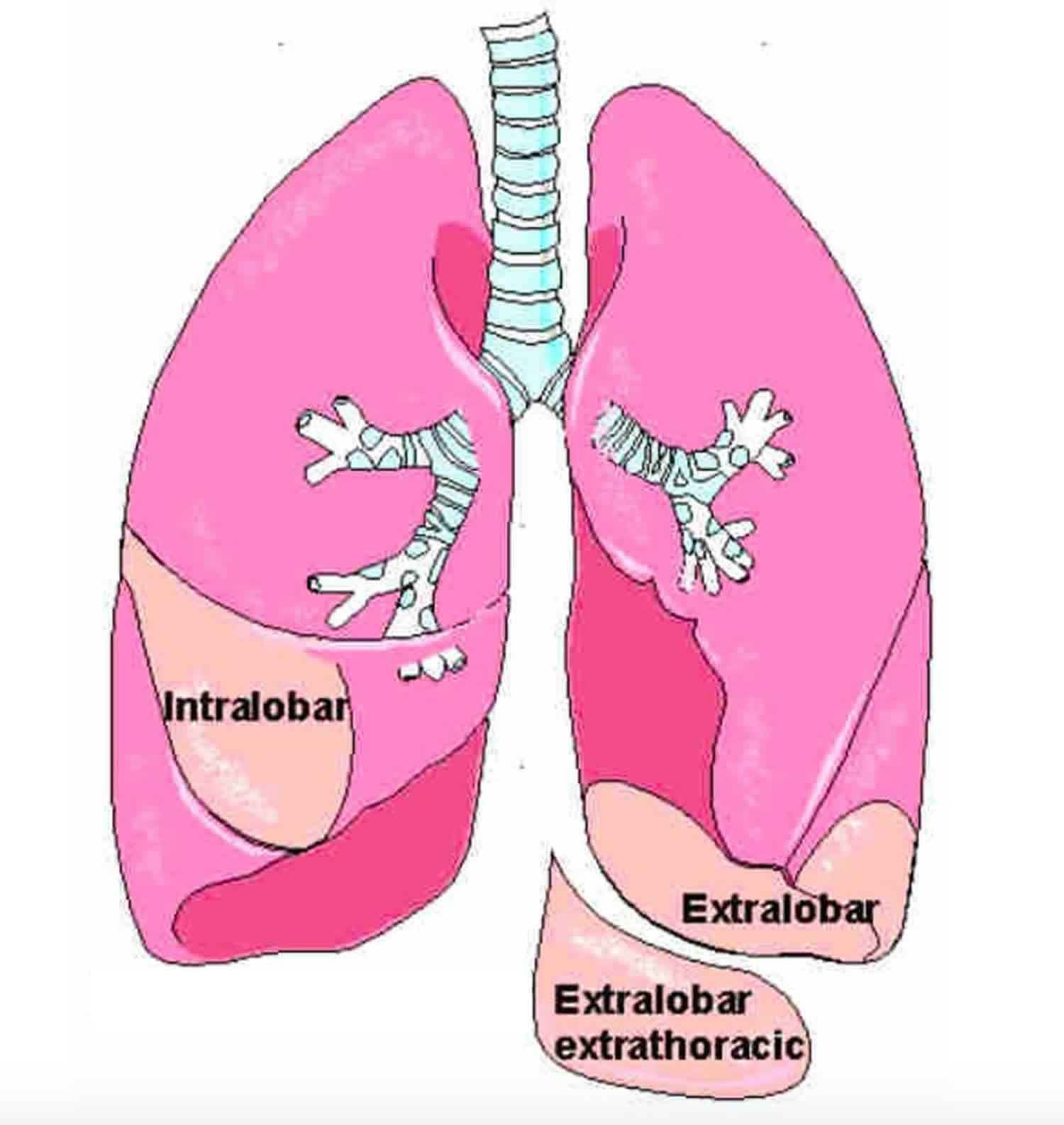

Bronchopulmonary sequestration is divided into two types:

- Intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration in which the mass forms inside the lungs. These lesions account for about 75% of cases of bronchopulmonary sequestration, affect males and females equally, and are generally isolated birth defects. All intralobar lesions require surgical removal (resection) after birth.

- Extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration in which the abnormal mass forms outside but nearby the lungs. In some instances, extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration may be located in the abdomen. These lesions account for only about 25% of bronchopulmonary sequestration cases, and are more likely to affect males than females. Small extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration can frequently be managed without surgery after birth, while large lesions will require surgery.

- Extralobar intrathoracic

- Extralobar subdiaphragmatic

Intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration which is the more common type, where the lesion lies within pleural layer surrounding the lobar lung and extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration which has its own pleural covering, maintaining complete anatomic separation from adjacent normal lung 6.

Most patients with intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration present in adolescence or early adulthood with recurrent pneumonias in the affected lobe 4. Patients with bronchopulmonary sequestration can be asymptomatic and the diagnosis achieved incidentally. Other presenting symptoms may include cough, hemoptysis, chest pain and dyspnea 7. Extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration is often identified on prenatal ultrasound and becomes symptomatic early in life, whereas intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration is more commonly identified later in life secondary to recurrent infection. Extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration rarely becomes infected because it is separated from the tracheobronchial tree by its own pleural investment 4.

Bronchopulmonary sequestration is one of several types of congenital lung lesions and may be confused with congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM). While similar in some ways, bronchopulmonary sequestration and CCAM are unique conditions that require individualized treatment. A child can also develop a hybrid lesion, which has characteristics of both a bronchopulmonary sequestration and CCAM. This unusual condition makes diagnosis challenging.

Treatment for bronchopulmonary sequestration depends on the type and size of lung lesion, as well as whether the condition is causing any serious health complications for mother or baby.

While some cases of small extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestrations will not require surgery, large extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestrations and all intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestrations can lead to breathing problems, infection, and life-threatening complications like heart failure. Surgery is needed to remove the abnormal tissue.

Most children with bronchopulmonary sequestration can be safely treated with surgery after birth. In rare cases — when the lesion has grown abnormally large, is restricting lung growth or impairing blood flow, putting your baby at risk for heart failure — fetal intervention may be necessary.

It has been generally believed that most patients should have their bronchopulmonary sequestration resected even if they are asymptomatic due to concerns regarding eventual complication, mainly infection of bronchopulmonary sequestration. However, this issue remains debatable since data regarding the long-term clinical course and outcome of those with unresected bronchopulmonary sequestration are sparse, particularly in the adult population 2. A cohort study included adults in their third to seventh decades of life without symptoms referable to the presence of bronchopulmonary sequestration and no relevant symptoms or events occurred during follow-up of patients with unresected bronchopulmonary sequestration 2.

Petersen et al. 8 reviewed the literature for patients above the age of 40 with intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration and found 15 cases including two patients from their own medical center. Most of these adult patients underwent surgical resection of their intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration. The largest study in the literature on bronchopulmonary sequestration is from China where Wei et al. 7 reported 2625 cases of bronchopulmonary sequestration including 132 adult patients. However, their report does not describe how many of their adult bronchopulmonary sequestration patients underwent surgical resection, associated surgical outcome, nor clinical course of patients who did not undergo surgical resection 7. In a study by Makhija et al. 6, 102 older patients (age 4 to 80 years) with congenital cystic lung disease undergoing surgical management were reported and included 20 with bronchopulmonary sequestration (20%); postsurgical complication rate of 9.8% for the entire cohort was reported.

Berna et al. 9 studied 26 adult patients with intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration all of whom underwent surgical resection. Hemoptysis or recurrent infection was present in 54%. All 26 patients underwent surgical resection of their bronchopulmonary sequestration including 20 patients (77%) who underwent lobectomies. Postoperative complication rate was 25% and included pleural empyema, hemoptysis, prolonged air leak, arrhythmia, and fistulae. All patients were alive and well at long-term follow-up (mean 36.5 months).

The surgical resection of sequestration carries the risk of complications; the surgical complication rate in a cohort was 28% which included chylous leak, intraoperative mild bleeding, chronic chest pain, arm numbness and pneumonia. No surgical mortality occurred. These results are similar to those reported by Berna et al 9.

Figure 1. Congenital pulmonary sequestration

Intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration

Intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration is a subtype of pulmonary sequestration. Intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration is the commoner type of pulmonary sequestration (four times commoner than extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration), accounting for 75% of all sequestrations and is characterized by the sequestration surrounded by normal lung tissue without its own pleural covering. Patients usually present before the third decade with recurrent infection. There is strong predilection for intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration towards the lower lobes (predominantly left lower lobe).

There is increasing data to support the concept of sequestrations stemming from recurrent infections that produce aberrant arterial vessels arising from the aorta 10. Feeding vessels include branches from the thoracic aorta (75%), abdominal aorta, intercostal artery or multiple arteries.

Extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration

Extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration is a subtype of bronchopulmonary sequestration. Extralobar pulmonary sequestration is usually encountered in infants, most being diagnosed before six months. Extralobar pulmonary sequestration is the less common type of pulmonary sequestration, accounting only for 15-25%. It is more common in male (M:F 4:1).

Extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration is covered by its own pleura and this is what differentiates extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration from intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration. There is strong predilection for extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration towards the left lower lobe (65-90%). Of these, 75% are found in the costophrenic sulcus on the left side. They may also be found in the mediastinum, pericardium, and within or below the diaphragm.

Extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration receives vascular supply mainly from the aorta (thoracic or abdominal) or from other arterial vessels (splenic, subclavian, gastric, intercostal or multiple vessels) and venous drainage can be either systemic or pulmonary.

Extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestrations are associated with other congenital malformations in more than 50% of cases, such as congenital diaphragmatic hernias, congenital pulmonary airway malformation (CPAM) type II (hybrid lesions), and congenital heart disease 11.

Bronchopulmonary sequestration causes

Scientists do not know what causes bronchopulmonary sequestration. Bronchopulmonary sequestration is believed to result from abnormal diverticulation of foregut and aberrant lung buds 12. Most clinicians believe the condition begins during prenatal development when an extra lung bud forms and migrates with the esophagus. Depending on when the extra lung bud forms, it may become part of one of the lungs (intralobar), or grow separately (extralobar).

Bronchopulmonary sequestration has not been linked to a genetic or chromosomal anomaly, and does not appear to run in families (is not hereditary).

The most frequently supported theory of pulmonary sequestration formation involves an accessory lung bud that develops from the ventral aspect of the primitive foregut. The pluripotential tissue from this additional lung bud migrates in a caudal direction with the normally developing lung. It receives its blood supply from vessels that connect to the aorta and cover the primitive foregut. These attachments to the aorta remain to form the systemic arterial supply of the sequestration 13

Early embryologic development of the accessory lung bud results in formation of the sequestration within normal lung tissue. The sequestration is encased within the same pleural covering. This is the intrapulmonary variant. In contrast, later development of the accessory lung bud results in the extrapulmonary type that may give rise to communication with the gastrointestinal tract. Both types of sequestration usually have arterial supply from the thoracic or abdominal aorta. Rarely, the celiac axis, internal mammary, subclavian, or renal artery may be involved 14.

Intrapulmonary sequestration occurs within the visceral pleura of normal lung tissue. Usually, no communication with the tracheobronchial tree occurs. The most common location is in the posterior basal segment, and nearly two thirds of pulmonary sequestrations appear in the left lung. Venous drainage is usually via the pulmonary veins 15. Foregut communication is very rare, and associated anomalies are uncommon.

Extrapulmonary sequestration is completely enclosed in its own pleural sac. It may occur above, within, or below the diaphragm, and nearly all appear on the left side. No communication with the tracheobronchial tree occurs. Venous drainage is usually via the systemic venous system. Foregut communication and associated anomalies, such as diaphragmatic hernia, are more common.

Bronchopulmonary sequestration symptoms

Symptoms of bronchopulmonary sequestration can vary, and depend on the size of the lesion.

After birth, children with bronchopulmonary sequestration may experience:

- No symptoms

- Trouble breathing

- Wheezing or shortness of breath

- Frequent lung infections like pneumonia

- Upper respiratory infections that take longer than usual to resolve

- Feeding difficulties and trouble gaining weight as infants

All suspected lung lesions, whether found before or after birth, require careful imaging. Determining the type, size and location of the lesion will guide treatment recommendations.

Intrapulmonary sequestration

Although an intrapulmonary sequestration is usually diagnosed later in childhood or adolescence, symptoms may begin early in childhood with multiple episodes of pneumonia. A chronic or recurrent cough is common. Intrapulmonary sequestration shares the visceral pleura that covers the adjacent lung tissue and is usually located in the posterobasal segment of the lower lobes. The thoracic or abdominal aorta often provides the arterial blood supply. Venous drainage is commonly provided to the left atrium via the pulmonary veins.

An elemental communication with other bronchi or lung parenchyma may be present, allowing infection to occur. Rarely, an esophageal bronchus may be present. Resolution of infection is usually slow and incomplete because of inadequate bronchial drainage.

Overdistension of the cystic mass with air can result in compression of normal lung tissue with impairment of cardiorespiratory function. Aeration probably occurs through the pores of Kohn.

Other congenital anomalies may appear in 10% of cases.

Extrapulmonary sequestration

Many patients present in infancy with respiratory distress and chronic cough. Lesions are commonly diagnosed coincidentally during investigation of, or surgery for, an associated congenital anomaly. Therefore, clinical symptoms may be absent or minor.

Extrapulmonary sequestration may manifest as gastrointestinal symptoms if communication with the gastrointestinal tract is present. As a result, infants may have feeding difficulties. In addition, extrapulmonary sequestration may manifest as recurrent lung infection, similar to the intrapulmonary form. This type of sequestration does not contain air unless communication with the foregut is present.

Bronchopulmonary sequestration diagnosis

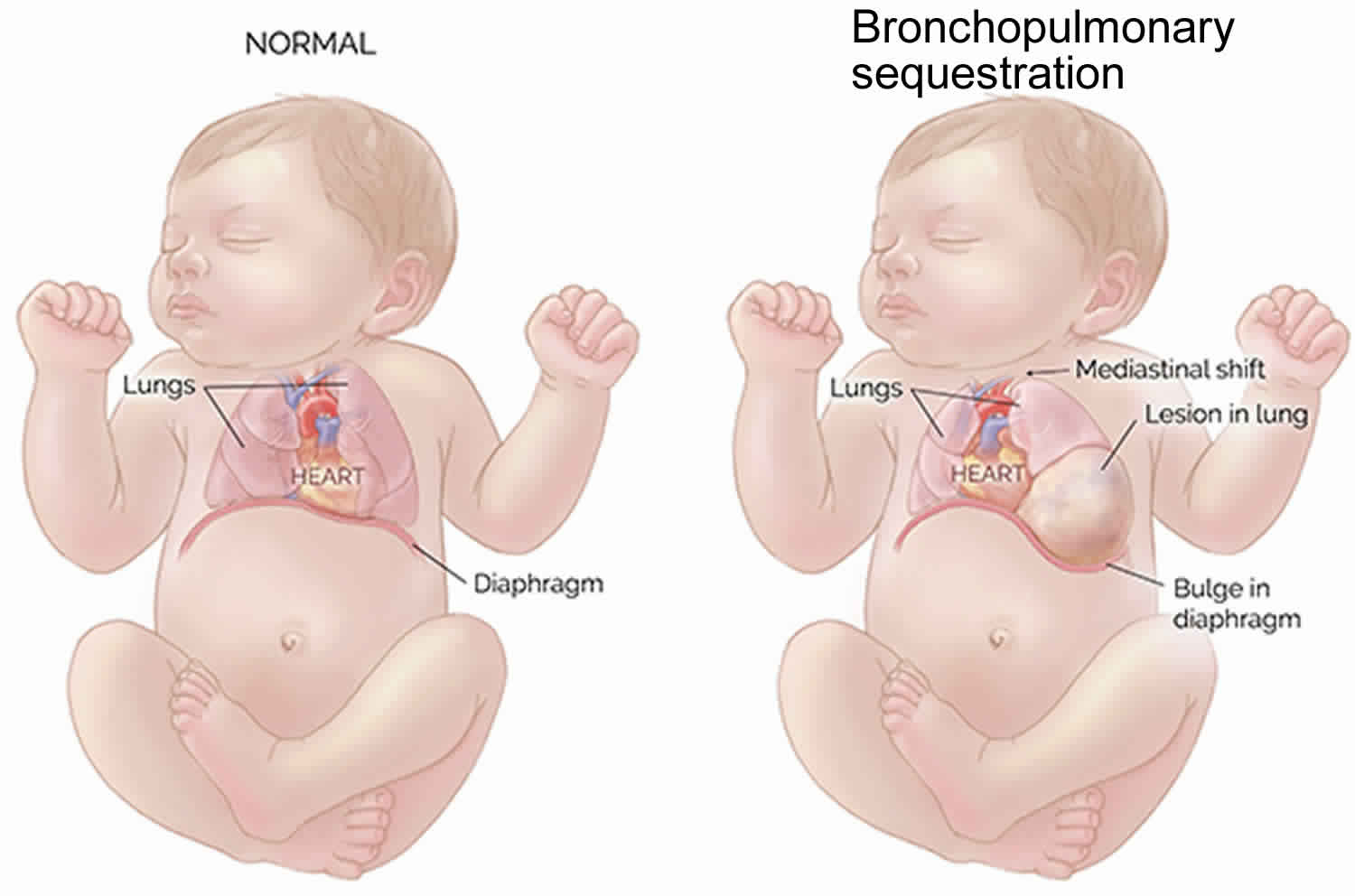

Thanks to improvements in prenatal imaging, most cases of bronchopulmonary sequestration are discovered during routine ultrasounds between 18 to 20 weeks’ gestation. Pulmonary sequestrations are diagnosed with a prenatal ultrasound showing a mass in the chest of the fetus. A solid mass will typically appear on the ultrasound as a bright spot in the fetus’s chest cavity. The mass may displace the heart from its normal position or push the diaphragm downward, but the key feature of a sequestration is the artery leading from the cystic mass directly to the aorta. This is what distinguishes a pulmonary sequestration from a congenital cystic adenomatoid malformation (CCAM). Expert fetal imaging specialists experienced in evaluating fetal lung lesions can detect the source of the blood flow to the lung lesion as well how blood is drained from the lesion. This is an important step to confirm an accurate diagnosis and distinguish between an intralobar and extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration, hybrid lesion, CCAM or other type of fetal lung lesions.

If you are carrying a baby suspected to have bronchopulmonary sequestration, you should be seen by a center with expertise in lung lesions for a more thorough examination.

Bronchopulmonary sequestration treatment

Nearly one-half of adult patients with pulmonary sequestration present with no relevant symptoms. The decision regarding surgical resection needs to weigh various factors including clinical manifestations related to bronchopulmonary sequestration, risk of surgical complications, comorbidities, and individual patient preferences.

Small or moderate-sized bronchopulmonary sequestrations that don’t change much during the pregnancy can be successfully managed after birth, usually with surgery to remove the abnormal lung tissue. These babies typically do not have any difficulty during pregnancy or after birth.

Management of an asymptomatic pulmonary sequestration with no connection to the surrounding lung is controversial; however, most experts advocate resection of bronchopulmonary sequestrations because of the likelihood of recurrent lung infection, high blood flow through the tissue can cause heart failure, the need for larger resection if the sequestration becomes chronically infected, and the possibility of hemorrhage from arteriovenous anastomoses 16. This surgery is quite safe even in the first year of life, and does not compromise lung function or development. These children will grow up normally and have normal lung function.

Surgical resection is the treatment of choice for patients who present with infection or symptoms resulting from compression of normal lung tissue.

Extrapulmonary lesions can usually be excised without loss of normal lung tissue.

Intrapulmonary lesions often require lobectomy because the margins of the sequestration may not be clearly defined. Complete thoracoscopic resection of pulmonary lobes in infants and children has been described with low mortality and morbidity 17.

Fetuses who do not have hydrops when bronchopulmonary sequestration is first detected must be followed closely with ultrasounds at least every week to look for the development of hydrops. Fetal hydrops is the build-up of excess fluid, which can be seen in the fetal abdomen, lungs, skin or scalp.

If the baby doesn’t develop hydrops, the medical team will continue to follow a “wait and see” approach with close follow-up. Many bronchopulmonary sequestrations begin to decrease in size before 26 weeks of pregnancy, and almost all can be safely dealt with after birth at a tertiary perinatal center. Some lesions even take care of themselves entirely.

A few fetuses develop fluid collection in the chest cavity, which may be treated by placing a catheter shunt to drain the chest fluid into the amniotic fluid.

If the fetus has a very large bronchopulmonary sequestration that will make resuscitation after delivery dangerous, a specialized delivery can be planned, called the ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure.

Management of pregnancy with bronchopulmonary sequestration

Depending on the gestational age of your baby and the size of the mass, you will continue to have regular ultrasounds to closely monitor the growth of the lung lesion.

Rarely, these masses can grow quite large, taking up valuable space in the chest. This can restrict normal lung growth and can lead to underdeveloped lungs which will not function adequately at birth. Large masses can also shift the heart and impair blood flow. This can lead to fetal heart failure (fetal hydrops) and cause the buildup of fluid in the fetus and placenta.

Some of these masses are associated with a large pleural effusion, or fluid collection in the chest cavity. This fluid collection can also compromise the ability of the fetal heart to function normally.

Over several visits, clinicians will determine how quickly your child’s bronchopulmonary sequestration is growing.

Fetal intervention for bronchopulmonary sequestration

Treatment for bronchopulmonary sequestration depends on the type and size of lung lesion, as well as whether the condition is causing any serious health complications.

Some babies with bronchopulmonary sequestration cannot wait for treatment after birth because the lesion is too large, growing too rapidly, or causing life-threatening complications in utero such as fetal heart failure.

Fetal interventions to treat bronchopulmonary sequestration include:

Draining fluid from the chest

A small number of bronchopulmonary sequestrations can develop a large pleural effusion, or accumulation of fluid in the chest, outside of the lung, which can compress the lungs and heart. This fluid can be drained prenatally and a shunt can be left in place to provide continued drainage of the fluid.

The shunting procedure itself is performed under ultrasound guidance. A large trocar (hollow needle) is guided through the mother’s abdomen and uterus, and into the fetal chest. The shunt is passed through the trocar to divert the accumulated fluid from the fetal chest to the amniotic sac. The shunt will remain until delivery. The goal of these procedures is to decrease the accumulation of fluid to ward off heart failure (fetal hydrops).

C-section to resection

Babies with large lung lesions can be safely delivered by C-section and be carried immediately to the adjacent operating room where expert fetal surgeons will remove the mass. After the mass is removed, a dedicated Neonatal Surgical Team will provide further specialized care for your baby.

Ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure

Rarely, a large bronchopulmonary sequestration may require a specialized delivery technique, such as the ex utero intrapartum treatment (EXIT) procedure. The EXIT procedure is performed in a Special Delivery Unit (SDU).

In an EXIT procedure, your surgical team will partially deliver the baby so that they are still attached to the placenta and receiving oxygen through the umbilical cord. This procedure allows time for fetal surgeons to establish an airway and remove the mass while the baby is still attached and supported by the mother. After removal, your baby will be delivered and our Neonatal Surgical Team will provide further specialized care.

Delivery of babies with bronchopulmonary sequestration

Mothers carrying babies with small lung lesions — without other associated anomalies — may be able to deliver at their local hospital, without the need for high-risk neonatal care. Babies with larger lesions, or those with complications or associated disorders, should be delivered in a center that offers expert care for both mother and baby in one location.

Babies with prenatally diagnosed lung lesions who will require treatment immediately or soon after birth are delivered in the Special Delivery Unit (SDU), specifically designed to keep mother and baby together and avoid transport of fragile infants.

Your baby will need immediate access to the Newborn/Infant Intensive Care Unit (NICU) and a dedicated Neonatal Surgical Team. Where a healthcare team experienced in performing complex, delicate procedures needed to establish an airway while delivering babies who may not be able to breathe on their own at birth, as well as any immediate surgeries that your baby might need is needed.

Surgery for bronchopulmonary sequestration after birth

Bronchopulmonary sequestration lesions can be successfully treated with surgery after birth.

- All intralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration lesions should be surgically removed because of an increased risk of infection as well as the potential for high blood flow through the tissue that can lead to heart failure later in life.

- Large extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration, especially those with high blood flow, may compromise your baby’s ability to breathe or put too much stress on your baby’s heart, and should be surgically removed.

- Small extralobar bronchopulmonary sequestration may not require surgery to remove the lesion.

Removing the bronchopulmonary sequestration mass when your child is young has multiple benefits, including promoting compensatory lung growth (ability of lungs to grow and fill the space in the chest) and avoiding potential complications such as lung infections.

First, you will come in for an appointment for your child to be evaluated by the surgical team. A CT scan with contrast will be performed to confirm the diagnosis and determine the exact location of your child’s lung lesion.

The average length of stay after lung lesion surgery is two to three days.

Follow-up care

Follow-up care for children with bronchopulmonary sequestration will depend on the treatment the child received.

Most children treated for small lesions after birth will only need monitoring for the first year after surgery to ensure normal lung growth and lung function. The majority will require no additional long-term follow-up care.

Children treated for more severe or complex lung lesions may require ongoing monitoring through childhood. For those who experience limited lung growth resulting in pulmonary hypoplasia, comprehensive long-term care with a focus on improving your child’s pulmonary health, evaluating neurodevelopmental growth, meeting nutritional needs, monitoring for late onset hearing loss or any surgical issues, and more.

Bronchopulmonary sequestration prognosis

Most babies with bronchopulmonary sequestration have a very good outcome and have normal lung function after their lesions are removed. This is due to rapid compensatory lung growth that occurs during childhood. Having surgery early maximizes this compensatory growth.

The pulmonary sequestrations remain the same size or grow with the fetus, but usually do not cause severe problems, probably because there is enough room for the normal part of the lung to grow. The mass may shrink in size before birth. In all these cases, the outlook for a normal life is excellent. These fetuses should be followed closely, delivered near term, and the pulmonary sequestration should be removed surgically after birth. Often the removal is an elective procedure in early childhood.

A small number of fetuses with pulmonary sequestrations may develop large pleural effusions — excess fluid in the chest cavity — and even signs of heart failure. Unlike congenital cystic adenomatoid malformations, which cause trouble because of their size, bronchopulmonary sequestrations may cause trouble because of the high blood flow through the tumor. These are the only cases that require treatment before birth.

Children with moderate to large lesions can also do extremely well, but their outlook depends on expert treatment to avoid potential complications. These babies require highly specialized expert care from time of diagnosis to delivery and surgery to ensure the best possible long-term outcomes.

- Liechty KW, Flake AW. Pulmonary vascular malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17(1):9–16.[↩]

- Alsumrain, M., Ryu, J.H. Pulmonary sequestration in adults: a retrospective review of resected and unresected cases. BMC Pulm Med 18, 97 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12890-018-0663-z[↩][↩][↩]

- Pryce DM. Lower accessory pulmonary artery with intralobar sequestration of lung; a report of seven cases. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1946;58(3):457–67.[↩]

- Walker CM, Wu CC, Gilman MD, Godwin JD, 2nd, Shepard J-AO, Abbott GF: The imaging spectrum of bronchopulmonary sequestration. Curr Probl Diagn Radiol 2014, 43(3):100–114.[↩][↩][↩]

- Berrocal T, Madrid C, Novo S, Gutiérrez J, Arjonilla A, Gómez-León N. Congenital anomalies of the tracheobronchial tree, lung, and mediastinum: embryology, radiology, and pathology. Radiographics. 2004;24(1):e17. doi:10.1148/rg.e17[↩]

- Makhija Z, Moir CR, Allen MS, Cassivi SD, Deschamps C, Nichols FC 3rd, Wigle DA, Shen KR. Surgical management of congenital cystic lung malformations in older patients. Ann Thorac Surg. 2011;91(5):1568–73. discussion 1573[↩][↩]

- Wei Y, Li F. Pulmonary sequestration: a retrospective analysis of 2625 cases in China. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2011;40(1):e39–42.[↩][↩][↩]

- Petersen G, Martin U, Singhal A, Criner GJ. Intralobar sequestration in the middle-aged and elderly adult: recognition and radiographic evaluation. Journal of Thoracic & Cardiovascular Surgery. 2003;126(6):2086–90.[↩]

- Berna P, Cazes A, Bagan P, Riquet M. Intralobar sequestration in adult patients. Interactive Cardiovascular & Thoracic Surgery. 2011;12(6):970–2.[↩][↩]

- Lee EY, Boiselle PM, Cleveland RH. Multidetector CT evaluation of congenital lung anomalies. Radiology. 2008;247(3):632-648. doi:10.1148/radiol.2473062124[↩]

- Hadley GP, Egner J. Gastric duplication with extralobar pulmonary sequestration: an uncommon cause of “colic”. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2001 Jun. 40(6):364.[↩]

- Telander RL, Lennox C, Sieber W. Sequestration of the lung in children. Mayo Clin Proc. 1976 Sep. 51(9):578-84.[↩]

- Corbett HJ, Humphrey GM. Pulmonary sequestration. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004 Mar. 5(1):59-68.[↩]

- Abel RM, Bush A, Chitty LS, Harcourt J, Nicholson AG. Congenital lung disease. Kendig’s Disorders of the Respiratory Tract in Children. 8th ed. Philadelphia, Pa: WB Saunders; 2012. 317-357.[↩]

- Alivizatos P, Cheatle T, de Leval M, Stark J. Pulmonary sequestration complicated by anomalies of pulmonary venous return. J Pediatr Surg. 1985 Feb. 20(1):76-9.[↩]

- Laberge JM, Bratu I, Flageole H. The management of asymptomatic congenital lung malformations. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2004. 5 Suppl A:S305-12.[↩]

- Albanese CT, Rothenberg SS. Experience with 144 consecutive pediatric thoracoscopic lobectomies. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2007 Jun. 17(3):339-41.[↩]