What is Carotid Artery Disease

Carotid artery disease is a disease in which a waxy substance called plaque builds up inside the carotid arteries 1. You have two common carotid arteries (see Figure 1. Common carotid artery), one on each side of your neck. They each divide into internal and external carotid arteries (see Figure 2. Internal and external carotid artery). The internal carotid arteries supply oxygen-rich blood to your brain. The external carotid arteries supply oxygen-rich blood to your face, scalp, and neck.

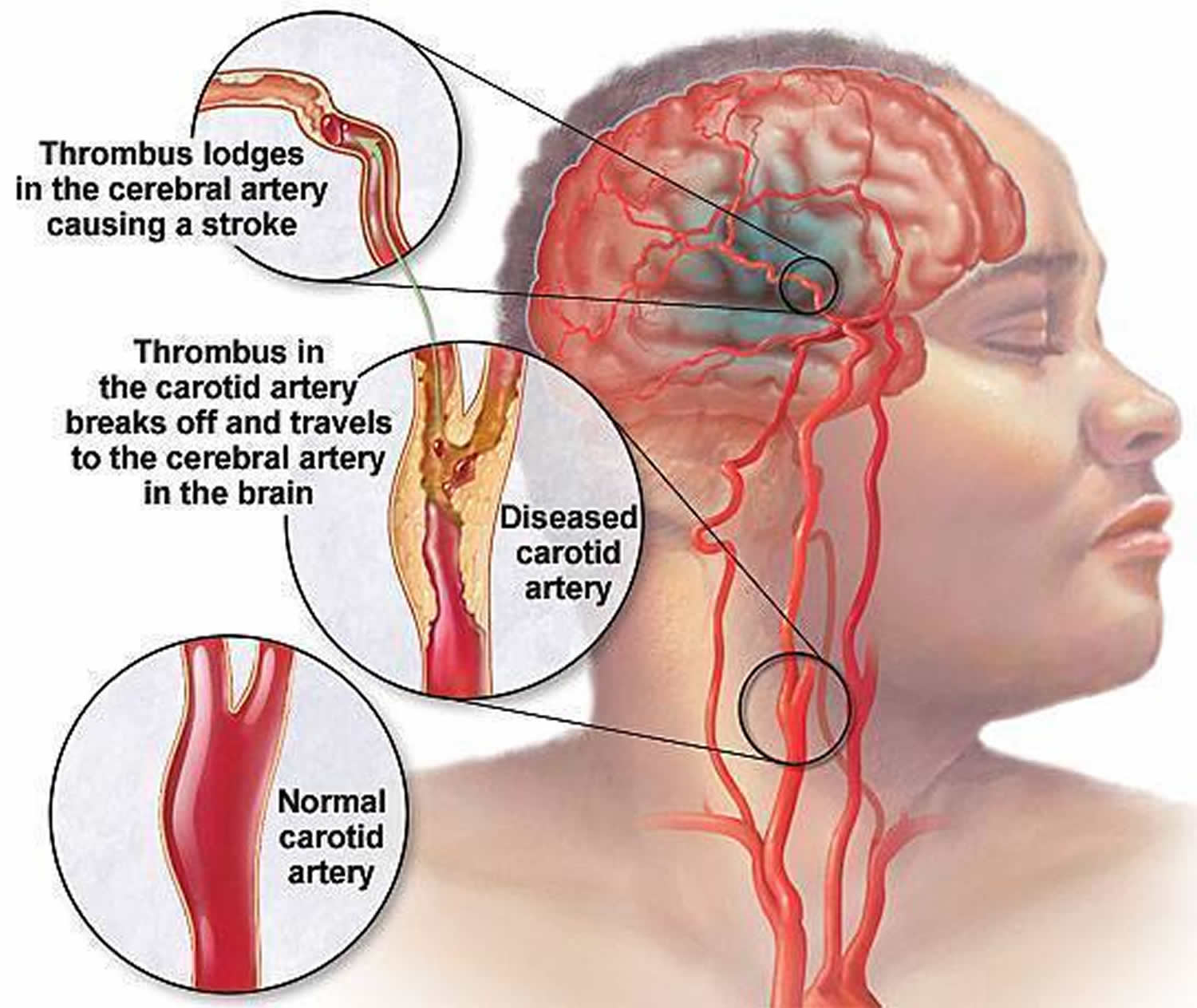

Plaque is made up of fat, cholesterol, calcium, and other substances found in the blood 2. Over time, plaque hardens and narrows your arteries. This limits the flow of oxygen-rich blood to your brain and other parts of your head.

When the plaque builds up in the wall including inside the carotid arteries, the condition is called atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis is a disease in which plaque builds up inside your arteries. As arterial plaque builds up over many years, an artery wall gets thicker. This narrows the opening, reducing blood flow and the supply of oxygen to brain. During the buildup of arterial plaque, you might not notice a problem until you have a significant blockage. Plaque buildup also makes it more likely that blood clots will form in your carotid arteries.

- Carotid artery disease may not cause signs or symptoms until the carotid arteries are severely narrowed or blocked. For some people, a stroke is the first sign of the disease.

Eventually, an area of plaque can rupture (break open) inside of the carotid artery. When this happens, blood cell fragments called platelets stick to the site of the injury. They may clump together to form blood clots. Blood clots can partly or fully block a carotid artery. If the clot becomes large enough, it can mostly or completely block blood flow of oxygen-rich blood to your brain causing stroke.

- Carotid artery disease is a major cause of stroke in the United States.

Other conditions, such as certain heart problems and bleeding in the brain, also can cause strokes. Lifestyle changes, medicines, and medical procedures can help prevent or treat carotid artery disease and may reduce the risk of stroke.

- If you think you’re having a stroke, you need urgent treatment. Call your local emergency number right away if you have symptoms of a stroke. Do not drive yourself to the hospital. You have the best chance for full recovery if treatment to open a blocked artery is given within 4 hours of symptom onset. The sooner treatment occurs, the better your chances of recovery.

A piece of plaque or a blood clot also can break away from the wall of the carotid artery. The plaque or clot can travel through the bloodstream and get stuck in one of the brain’s smaller arteries. This can block blood flow in the artery and cause a stroke.

Stroke is the third most common cause of death worldwide after ischemic heart disease and cancer. Approximately 30% of patients die within the first year of having a stroke and another 50% are left disabled 3.

Stroke Warning Signs

The signs and symptoms of stroke may include:

- Sudden weakness or numbness in the face or limbs, often on only one side of the body

- The inability to move one or more of your limbs

- Trouble speaking or understanding speech

- Sudden trouble seeing in one or both eyes

- Dizziness or loss of balance

- A sudden, severe headache with no known cause

Call your local emergency number for help as soon as symptoms start. Do not drive yourself to the hospital. It’s very important to get checked and treated as soon as possible.

If you’re a candidate for clot-busting therapy, you have the best chance for full recovery if treatment to open a blocked artery is given within 4 hours of symptom onset. The sooner treatment occurs, the better your chances of recovery.

Make those close to you aware of stroke symptoms and the need for urgent action. Learning the signs and symptoms of a stroke will allow you to help yourself or someone close to you lower the risk of damage or death due to a stroke.

Where is the carotid artery

The left and right common carotid arteries diverge into the internal and external carotid arteries. The external carotid artery courses upward on the side of the head, giving off branches to structures in the neck, face, jaw, scalp, and base of the skull. The internal carotid artery begins lateral to the external carotid artery, then extends medially to follow a deep course upward along the pharynx to the base of the skull. Entering the cranial cavity, it provides the major blood supply to the brain. Near the base of each internal carotid artery is an enlargement called a carotid sinus. Like the aortic arch, these structures contain baroreceptors

that control blood pressure.

External carotid artery via its branches supply blood, oxygen and nutrients to your:

- Larynx and thyroid gland

- Tongue and salivary glands

- Pharynx, palate, chin, lips, and nose

- Posterior scalp, meninges, and neck muscles

- Ear and lateral scalp

- Teeth, jaw, cheek, and eyelids

- Parotid salivary gland and surface of the face and scalp

Internal carotid artery via its branches supply blood, oxygen and nutrients to your:

- Eye and eye muscles

- Choroid plexus and brain

- Frontal lobes of the brain

- Parietal lobes of brain

Figure 1. Common carotid artery

Figure 2. External and Internal carotid artery

Figure 3. Cerebrovascular system

Figure 5. Branches of the Internal carotid artery supplying the brain (including frontal & parietal lobe) and the eye (& eye muscles)

Figure 6. Stroke

What causes carotid artery disease ?

Carotid artery disease seems to start when damage occurs to the inner layers of the carotid arteries. Major factors that contribute to damage include 4:

- Smoking

- High levels of certain fats and cholesterol in the blood

- High blood pressure

- High levels of sugar in the blood due to insulin resistance, prediabetes or diabetes

When damage occurs, your body starts a healing process. The healing may cause plaque to build up where the arteries are damaged.

The plaque in an artery can crack or rupture. If this happens, blood cell fragments called platelets will stick to the site of the injury and may clump together to form blood clots.

The buildup of plaque or blood clots can severely narrow or block the carotid arteries. This limits the flow of oxygen-rich blood to your brain, which can cause a stroke.

Who is at risk for carotid artery disease ?

The major risk factors for carotid artery disease, listed below, also are the major risk factors for coronary heart disease (also called coronary artery disease) and peripheral artery disease 5.

- Diabetes. With this disease, the body’s blood sugar level is too high because the body doesn’t make enough insulin or doesn’t use its insulin properly. People who have diabetes are four times more likely to have carotid artery disease than are people who don’t have diabetes.

- Family history of atherosclerosis. People who have a family history of atherosclerosis are more likely to develop carotid artery disease.

- High blood pressure (Hypertension). Blood pressure is considered high if it stays at or above 140/90 mmHg over time. If you have diabetes or chronic kidney disease, high blood pressure is defined as 130/80 mmHg or higher. (The mmHg is millimeters of mercury—the units used to measure blood pressure.)

- Lack of physical activity. Too much sitting (sedentary lifestyle) and a lack of aerobic activity can worsen other risk factors for carotid artery disease, such as unhealthy blood cholesterol levels, high blood pressure, diabetes, and overweight or obesity.

- Metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is the name for a group of risk factors that raise your risk for stroke and other health problems, such as diabetes and heart disease. The five metabolic risk factors are a large waistline (abdominal obesity), a high triglyceride level (a type of fat found in the blood), a low HDL cholesterol level, high blood pressure, and high blood sugar. Metabolic syndrome is diagnosed if you have at least three of these metabolic risk factors.

- Older age. As you age, your risk for atherosclerosis increases. The process of atherosclerosis begins in youth and typically progresses over many decades before diseases develop.

- Overweight or obesity. The terms “overweight” and “obesity” refer to body weight that’s greater than what is considered healthy for a certain height.

- Smoking. Smoking can damage and tighten blood vessels, lead to unhealthy cholesterol levels, and raise blood pressure. Smoking also can limit how much oxygen reaches the body’s tissues.

- Unhealthy blood cholesterol levels. This includes high LDL (“bad”) cholesterol) and low HDL (“good”) cholesterol.

- Unhealthy diet. An unhealthy diet can raise your risk for carotid artery disease. Foods that are high in saturated and trans fats, cholesterol, sodium, and sugar can worsen other risk factors for carotid artery disease.

Having any of these risk factors does not guarantee that you’ll develop carotid artery disease. However, if you know that you have one or more risk factors, you can take steps to help prevent or delay the disease.

If you have plaque buildup in your carotid arteries, you also may have plaque buildup in other arteries. People who have carotid artery disease also are at increased risk for coronary heart disease.

What are the signs and symptoms of carotid artery disease ?

Carotid artery disease may not cause signs or symptoms until it severely narrows or blocks a carotid artery. Signs and symptoms may include a bruit, a transient ischemic attack or a stroke 6.

Bruit

During a physical exam, your doctor may listen to your carotid arteries with a stethoscope. He or she may hear a whooshing sound called a bruit. This sound may suggest changed or reduced blood flow due to plaque buildup. To find out more, your doctor may recommend tests.

Not all people who have carotid artery disease have bruits.

Transient Ischemic Attack (Mini-Stroke)

For some people, having a transient ischemic attack (TIA), or “mini-stroke,” is the first sign of carotid artery disease. During a mini-stroke, you may have some or all of the symptoms of a stroke. However, the symptoms usually go away on their own within 24 hours.

Stroke and mini-stroke symptoms may include:

- A sudden, severe headache with no known cause

- Dizziness or loss of balance

- Inability to move one or more of your limbs

- Sudden trouble seeing in one or both eyes

- Sudden weakness or numbness in the face or limbs, often on just one side of the body

- Trouble speaking or understanding speech

Even if the symptoms stop quickly, call your local emergency number for emergency help. Do not drive yourself to the hospital. It’s important to get checked and to get treatment started as soon as possible.

- A mini-stroke is a warning sign that you’re at high risk of having a stroke. You shouldn’t ignore these symptoms. Getting medical care can help find possible causes of a mini-stroke and help you manage risk factors. These actions might prevent a future stroke.

Although a mini-stroke may warn of a stroke, it doesn’t predict when a stroke will happen. A stroke may occur days, weeks, or even months after a mini-stroke.

Stroke

The symptoms of a stroke are the same as those of a mini-stroke, but the results are not. A stroke can cause lasting brain damage; long-term disability, such as vision or speech problems or paralysis (an inability to move); or death. Most people who have strokes have not previously had warning mini-strokes.

Getting treatment for a stroke right away is very important. You have the best chance for full recovery if treatment to open a blocked artery is given within 4 hours of symptom onset. The sooner treatment occurs, the better your chances of recovery.

- Call local emergency number for emergency help as soon as symptoms occur. Do not drive yourself to the hospital. It’s very important to get checked and to get treatment started as soon as possible.

Make those close to you aware of stroke symptoms and the need for urgent action. Learning the signs and symptoms of a stroke will allow you to help yourself or someone close to you lower the risk of brain damage or death due to a stroke.

How is carotid artery disease diagnosed ?

Your doctor will diagnose carotid artery disease based on your medical history, a physical exam, and test results 7.

Medical History

Your doctor will find out whether you have any of the major risk factors for carotid artery disease. He or she also will ask whether you’ve had any signs or symptoms of a mini-stroke or stroke.

Physical Exam

To check your carotid arteries, your doctor will listen to them with a stethoscope. He or she will listen for a whooshing sound called a bruit. This sound may indicate changed or reduced blood flow due to plaque buildup. To find out more, your doctor may recommend tests.

Diagnostic Tests

The following tests are common for diagnosing carotid artery disease. If you have symptoms of a mini-stroke or stroke, your doctor may use other tests as well.

- Carotid Ultrasound

Carotid ultrasound (also called sonography) is the most common test for diagnosing carotid artery disease. It’s a painless, harmless test that uses sound waves to create pictures of the insides of your carotid arteries. This test can show whether plaque has narrowed your carotid arteries and how narrow they are.

A standard carotid ultrasound shows the structure of your carotid arteries. A Doppler carotid ultrasound shows how blood moves through your carotid arteries.

- Carotid Angiography

Carotid angiography is a special type of x ray. This test may be used if the ultrasound results are unclear or don’t give your doctor enough information.

For this test, your doctor will inject a substance (called contrast dye) into a vein, most often in your leg. The dye travels to your carotid arteries and highlights them on x-ray pictures.

- Magnetic Resonance Angiography

Magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) uses a large magnet and radio waves to take pictures of your carotid arteries. Your doctor can see these pictures on a computer screen.

For this test, your doctor may give you contrast dye to highlight your carotid arteries on the pictures.

- Computed Tomography Angiography

Computed tomography angiography, or CT angiography, takes x-ray pictures of the body from many angles. A computer combines the pictures into two- and three-dimensional images.

For this test, your doctor may give you contrast dye to highlight your carotid arteries on the pictures.

How is carotid artery disease treated ?

Treatments for carotid artery disease may include heart-healthy lifestyle changes, medicines, and medical procedures 8. The goals of treatment are to stop the disease from getting worse and to prevent a stroke. Your treatment will depend on your symptoms, how severe the disease is, and your age and overall health.

Heart-Healthy Lifestyle Changes

Your doctor may recommend heart-healthy lifestyle changes if you have carotid artery disease. Heart-healthy lifestyle changes include:

- Heart-healthy eating

- Aiming for a healthy weight

- Managing stress

- Physical activity

- Quitting smoking

Medicines

If you have a stroke caused by a blood clot, you may be given a clot-dissolving, or clot-busting, medication. This type of medication must be given within 4 hours of symptom onset. The sooner treatment occurs, the better your chances of recovery. If you think you’re having a stroke, call your local emergency number right away for emergency care.

Medicines to prevent blood clots are the mainstay treatment for people who have carotid artery disease. They prevent platelets from clumping together and forming blood clots in your carotid arteries, which can lead to a stroke. Two common medications are:

- Aspirin

- Clopidogrel

Sometimes lifestyle changes alone aren’t enough to control your cholesterol levels. For example, you also may need statin medications to control or lower your cholesterol. By lowering your blood cholesterol level, you can decrease your chance of having a heart attack or stroke. Doctors usually prescribe statins for people who have:

- Diabetes

- Heart disease or have had a stroke

- High LDL cholesterol levels

Doctors may discuss beginning statin treatment with those who have an elevated risk for developing heart disease or having a stroke.

You may need other medications to treat diseases and conditions that damage the carotid arteries. Your doctor also may prescribe medications to:

- Lower your blood pressure.

- Lower your blood sugar level.

- Prevent blood clots from forming, which can lead to stroke.

- Prevent or reduce inflammation.

Take all medicines regularly, as your doctor prescribes. Don’t change the amount of your medicine or skip a dose unless your doctor tells you to. Your health care team will help find a treatment plan that’s right for you.

Carotid Artery Surgery

You may need a medical procedure if you have symptoms caused by the narrowing of the carotid artery. Doctors use one of two methods to open narrowed or blocked carotid arteries: carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery angioplasty and stenting 9.

Carotid Endarterectomy

Carotid endarterectomy is also known as carotid artery surgery that removes plaque buildup from inside a carotid artery in your neck 10. Carotid endarterectomy is mainly for people whose carotid arteries are blocked 50 percent or more. This surgery is done to restore normal blood flow to the brain to prevent a stroke if you already have symptoms of reduced blood flow. Carotid endarterectomy also may be performed preventively if a diagnostic test such as carotid ultrasound shows significant blockage that is likely to trigger a stroke. Carotid endarterectomy is not a cure. Your arteries can become blocked again if your underlying condition, such as high blood cholesterol, is not controlled and causes new plaque buildup.

Carotid endarterectomy is done in a hospital. You may have general anesthesia and will not be awake or feel pain during the surgery 10. Your surgeon instead may decide to use local anesthesia to numb only the part of your body being worked on so that he or she can check your brain’s reaction to the decreased blood flow during surgery. You also will be given medicine to relax you during the surgery. Your vital signs will be monitored during surgery. You will lie on your back on an operating table with your head turned to one side. Your surgeon will make an incision, or cut, on your neck to expose the blocked section of the carotid artery. Your surgeon will cut into the affected artery and remove the plaque through this cut. A temporary flexible tube may be inserted so blood can flow around the blocked area as the plaque is cleared. After removing the plaque from your artery, the surgeon will close the artery and neck incisions with stitches.

After surgery, you will recover in the hospital for one to two days. Your neck may hurt for a few days, and you may find it hard to swallow. Your doctor may prescribe medicine to prevent clots and suggest steps to keep your carotid arteries healthy.

Carotid endarterectomy is fairly safe when performed by experienced surgeons. However, serious complications such as clotting, stroke, or death may occur. Taking anticlotting medicines before and after surgery can reduce this risk. Other complications may include a reaction to anesthesia, short-term nerve injury that causes temporary numbness in your face or tongue, bleeding, infection, high blood pressure, heart attack, and seizure. The risk of complications is higher in women, older people, those with certain conditions such as chronic kidney disease or diabetes, and those with other serious medical conditions.

After the carotid artery surgery

You may have a drain in your neck that goes into your incision. It will drain fluid that builds up in the area. It will be removed within a day.

After carotid artery surgery, your doctor may want you to stay in the hospital overnight so that nurses can watch you for any signs of bleeding, stroke, or poor blood flow to your brain. You may be able to go home the same day if your operation is done early in the day and you are doing well.

Risks of anesthesia are 9:

- Allergic reactions to medicines

- Breathing problems

Risks of carotid surgery are 9:

- Blood clots or bleeding in the brain

- Brain damage

- Heart attack

- More blockage of the carotid artery over time

- Seizures

- Stroke

- Swelling near your airway (the tube you breathe through)

- Infection.

Outlook (Prognosis) for carotid artery surgery

Carotid artery surgery may help lower your chance of having a stroke. But you will need to make lifestyle changes to help prevent plaque buildup, blood clots, and other problems in your carotid arteries over time. You may need to change your diet and start an exercise program, if your doctor tells you exercise is safe for you. It is also important to stop smoking.

Figure 7. Carotid endarterectomy

Note: The illustration shows the process of carotid endarterectomy. Figure A shows a carotid artery with plaque buildup. The inset image shows a cross-section of the narrowed carotid artery. Figure B shows how the carotid artery is cut and how the plaque is removed. Figure C shows the artery stitched up and normal blood flow restored. The inset image shows a cross-section of the artery with plaque removed and normal blood flow restored.

[Source 8]Carotid Artery Angioplasty and Stenting

Doctors use a procedure called angioplasty to widen the carotid arteries and restore blood flow to the brain.

A thin tube with a deflated balloon on the end is threaded through a blood vessel in your neck to the narrowed or blocked carotid artery. Once in place, the balloon is inflated to push the plaque outward against the wall of the artery.

A stent (a small mesh tube) is then put in the artery to support the inner artery wall. The stent also helps prevent the artery from becoming narrowed or blocked again.

Carotid angioplasty and stenting is done using a small surgical cut 11:

- Your surgeon will make a surgical cut in your groin after using some numbing medicine. You will also be given medicine to relax you.

- The surgeon places a catheter (a flexible tube) through the cut into an artery. It is carefully moved up to your neck to the blockage in your carotid artery.

- Moving x-ray pictures (fluoroscopy) are used to see the artery and guide the catheter to the correct position.

- Next, the surgeon will move a wire through the catheter to the blockage. Another catheter with a very small balloon on the end will be pushed over this wire and into the blockage. Then the balloon is inflated.

- The balloon presses against the inside wall of your artery. This opens the artery and allows more blood to flow to your brain. A stent (a wire mesh tube) may also be placed in the blocked area. The stent is inserted at the same time as the balloon catheter. It expands with the balloon. The stent is left in place to help keep the artery open.

- The surgeon then removes the balloon.

Carotid angioplasty and stenting has developed as a good alternative to surgery, when done by experienced operators. Certain factors may favor stenting, such as:

- The person is too ill to have carotid endarterectomy.

- The location of the narrowing in the carotid artery makes surgery harder.

- The person has had neck or carotid surgery in the past.

- The person has had radiation to the neck.

Risks of carotid angioplasty and stent placement, which depend on factors such as age, are 11:

- Allergic reaction to dye

- Blood clots or bleeding at the site of surgery

- Brain damage

- Clogging of the inside of the stent (in-stent restenosis)

- Heart attack

- Kidney failure (higher risk in people who already have kidney problems)

- More blockage of the carotid artery over time

- Seizures (this is rare)

- Stroke.

After the carotid angioplasty and stenting

After surgery, you may need to stay in the hospital overnight so that you can be watched for any signs of bleeding, stroke, or poor blood flow to your brain. You may be able to go home the same day if your procedure is done early in the day and you are doing well. Your provider will talk to you about how to care for yourself at home.

Outlook (Prognosis) for carotid angioplasty and stenting

Carotid artery angioplasty and stenting may help lower your chance of having a stroke. But you will need to make lifestyle changes to help prevent plaque buildup, blood clots, and other problems in your carotid arteries over time. You may need to change your diet and start an exercise program if your provider tells you exercise is safe for you.

Figure 8. Carotid angioplasty and stenting

Note: The illustration shows the process of carotid artery stenting. Figure A shows an internal carotid artery that has plaque buildup and reduced blood flow. The inset image shows a cross-section of the narrowed carotid artery. Figure B shows a stent being placed in the carotid artery to support the inner artery wall and keep the artery open. Figure C shows normal blood flow restored in the stent-widened artery. The inset image shows a cross-section of the stent-widened artery.

[Source 8]How can carotid artery disease be prevented ?

Taking action to control your risk factors can help prevent or delay carotid artery disease and stroke. Your risk for carotid artery disease increases with the number of risk factors you have.

One step you can take is to make heart-healthy lifestyle changes, which can include 12:

- Heart-Healthy Eating. Following heart-healthy eating is an important part of a healthy lifestyle. Dietary Approaches to Stop Hypertension (DASH) is a program that promotes heart-healthy eating.

- Aiming for a Healthy Weight. If you’re overweight or obese, work with your doctor to create a reasonable plan for weight loss. Controlling your weight helps you control risk factors for carotid artery disease.

- Physical Activity. Be as physically active as you can. Physical activity can improve your fitness level and your health. Ask your doctor what types and amounts of activity are safe for you. Read more about Physical Activity and Your Heart.

- Quit Smoking. If you smoke, quit. Talk with your doctor about programs and products that can help you quit.

Other steps that can prevent or delay carotid artery disease include knowing your family history of carotid artery disease. If you or someone in your family has carotid artery disease, be sure to tell your doctor.

If lifestyle changes aren’t enough, your doctor may prescribe medicines to control your carotid artery disease risk factors. Take all of your medicines as your doctor advises.

What is Carotid Artery Stenosis ?

Carotid artery stenosis is the narrowing of the carotid arteries that run along each side of the neck. These arteries provide blood flow to the brain. Over time,

plaque (a fatty, waxy substance) can build up and harden the arteries, limiting the flow of blood to the brain.

Carotid artery stenosis is one of many risk factors for stroke, a leading cause of death and disability in the United States. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) conservatively estimate that about 41,000 strokes may be attributed to extracranial internal carotid artery stenosis annually in the United States 13. Population-based studies have estimated that ~ 15% of ischemic strokes are caused by large vessel atherosclerosis, with extracranial internal carotid artery stenosis significantly more common than extracranial internal carotid artery occlusion or intracranial atherosclerotic disease 14, 15, 16. More importantly, for patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack attributed to severe (> 70%) extracranial internal carotid artery stenosis, prompt revascularization with carotid endarterectomy produces a dramatic reduction in recurrent stroke risk 17.

This study 18 shows that extracranial internal carotid artery atherosclerosis is the most important cause of large vessel stroke. Although this study has documented that a substantial number of strokes are attributable to internal carotid artery stenosis, most patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis do not subsequently have strokes. Thus, their data do not imply that all patients with asymptomatic carotid stenosis should undergo revascularization 18.

Fortunately, carotid artery stenosis is uncommon—about ½ to 1% of the population have the condition. The main risk factors are older age, being male, high blood pressure, smoking, high blood cholesterol, diabetes, and heart disease.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force is an independent group of national experts in prevention and evidence based medicine. The Task Force works to improve the health of all Americans by making evidence-based recommendations about clinical preventive services such as screenings, counseling services, or preventive medicines. The recommendations apply to people with no signs or symptoms of the disease being discussed. To develop a recommendation statement, Task Force members consider the best available science and research on a topic.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 19 reviewed studies on the benefits and harms of screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. They found that screening in the general population has little or no benefit for preventing stroke.

The Task Force also found that carotid artery stenosis screening has potential harms 19. Ultrasound screening does not by itself cause physical harm. However, this screening often leads to a cascade of follow-up testing and surgeries that can cause serious harms, including stroke, heart attack or death 19. In addition, screening all adults will lead to many false-positive results because few people have carotid artery stenosis 19. This is when a test result says a person has a condition that he or she actually does not have. False-positive results lead to unneeded tests and surgeries.

The Task Force’s final recommendation on screening for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis is based on the quality and strength of the clinical evidence about the potential benefits and harms of screening for preventing strokes. It also is based on the size of the potential benefits and harms. Task Force recommendation grades are explained in the box at the end of this fact sheet 20. When the Task Force recommends against screening (Grade D – Not Recommended), it is because it causes more potential harms than benefits.

Symptomatic vs Aymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis

A clear separation between symptomatic and asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis is critical. Extrapolations on the natural history with medical treatment only or on the benefit from invasive procedures are based on precise definitions of symptomatic and asymptomatic disease 21. A patient with carotid artery stenosis is considered symptomatic if the patient has transient or permanent focal neurologic symptoms related to the ipsilateral retina or the cerebral hemisphere 21. Symptoms of carotid artery stenosis include ipsilateral transient visual obscuration (amaurosis fugax) from retinal ischemia; contralateral weakness or numbness of an arm, a leg, or the face, or of a combination of these sites; visual field defect; dysarthria; and, in the case of dominant (usually left) hemisphere involvement, aphasia 21.

In daily clinical practice, carotid artery stenosis is found in many patients during evaluation of ill-defined episodes of “dizziness,” generalized subjective weakness, syncope or near-syncope episodes, “blurry vision,” or transient positive visual phenomena (such as “floaters” or “stars”). These nonspecific symptoms in patients with carotid artery stenosis do not qualify as symptomatic ischemic events; these patients are considered asymptomatic even in the presence of high-grade carotid artery stenosis 21.

How is carotid artery stenosis diagnosed ?

Carotid Bruits

Carotid auscultation should be part of the routine physical examination of patients with risk factors for vascular disease. Although carotid bruits have limited value for the diagnosis of carotid artery stenosis, they are good markers of generalized atherosclerosis. The presence of a carotid bruit is associated with increased risk of vascular disease, including stroke, myocardial infarction, and cardiovascular death 22.

For asymptomatic patients with vascular risk factors, carotid auscultation is a sufficient screening test. However, for patients with symptoms of transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke, the evaluation for carotid artery disease cannot be limited to auscultation of the neck because carotid bruits have relatively low sensitivity for the detection of moderate or severe carotid artery stenosis 23. Specificity is good for carotid artery disease in general, but it is actually lower for greater degrees of stenosis 23. Because bruits are generated by turbulent flow, they may be strong with mild stenosis and may even disappear when the stenosis becomes critical and causes marked restriction of flow. Therefore, symptomatic patients must be evaluated with imaging studies.

Imaging Studies

The definition of hemodynamically significant carotid artery stenosis is based on data from the randomized controlled trials on carotid endarterectomy. Exact quantification of the degree of stenosis is crucial in selecting proper treatment. This quantification is particularly important for patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis because of the marginal benefit they receive from surgery.

Doppler ultrasonography, which is readily available and noninvasive, is usually the first diagnostic imaging tool used to screen for carotid artery stenosis. However, it is highly dependent on operator experience and skill. When compared with catheter angiography, Doppler ultrasonography has a sensitivity of 86% and a specificity of 87% for the detection of hemodynamically significant carotid artery stenosis 24.

Catheter angiography is the criterion standard for defining the degree of stenosis and the morphologic features of the offending plaque. However, catheter angiography is neither feasible nor recommended in every patient because of its risks and costs. Computed tomographic angiography and magnetic resonance angiography have gained increasing popularity for use in the diagnosis of carotid artery stenosis, often replacing conventional catheter angiography. In our practice, magnetic resonance angiography or computed tomographic angiography is used as a confirmatory test after results of a Doppler study are suggestive of hemodynamically significant stenosis in an asymptomatic patient. Among symptomatic patients, a Doppler study is done as part of the emergency evaluation of every patient with transient ischemic attack or stroke 25. If a patient is considered for invasive treatment, these angiographic techniques are subsequently performed for improved definition of the stenosis. Invasive treatment is considered for symptomatic patients with stenosis greater than 50% 26 and for asymptomatic patients with stenosis greater than 60% 27, 28.

Carotid artery occlusion may be suspected because of ultrasonographic results, but it should be confirmed with noninvasive or invasive angiography, especially in symptomatic patients. For an occluded carotid artery, invasive treatment has no role except in the cases of a few carefully selected patients.

Symptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis Treatment

Prompt evaluation and triage of patients with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis are essential to minimize the risk of early recurrent cerebrovascular events. Prospective studies have shown that the risk of ipsilateral stroke is high within the first 90 days, and especially within the first month, after a transient ischemic attack 29. Urgent initiation of treatment can reduce this risk by up to 80% 29.

Recently, a scoring system was proposed, prospectively validated, and widely adopted to estimate the short-term risk of ipsilateral stroke after a transient ischaemic attack 30 (Table 1). The system is named with the acronym ABCD 22, derived from the 5 main components used to compound the score:

- Age,

- Blood pressure,

- Clinical features,

- Duration of symptoms, and

- Diabetes mellitus.

A patient with a transient ischaemic attack and an ABCD 22 score of 0 to 3 has a 1.2% risk of stroke within 7 days, as opposed to a 5.9% risk with a score of 4 or 5 and an 11.7% risk with a score of 5 or 6 30. High ABCD scores appear to identify patients with moderate or severe carotid artery stenosis 29. In the emergency department, doctors also perform screening with carotid duplex ultrasonography for all patients with suspected anterior circulation transient ischaemic attack. This practice has been useful for patient triage and has been associated with a low rate of strokes in the first week after the transient ischaemic attack 25.

Table 1. Criteria and Points of the ABCD Scoring System

[Source 21]Patients with symptomatic severe carotid artery stenosis should undergo invasive treatment unless the risk of the intervention is considered to be prohibitively high (e.g, extremely severe cardiopulmonary disease, recent cerebral infarction of large size or with hemorrhagic conversion) 21. In addition, aggressive treatment of vascular risk factors and antiplatelet therapy must be initiated promptly because they are crucial to the prevention of recurrent strokes after carotid revascularization.

Gradual blood pressure reduction (ie, over the period of a few days) is safe in most patients 31, but sudden decreases in blood pressure should be avoided, and antihypertensive therapy should be administered cautiously for patients with severe bilateral stenosis or critical unilateral stenosis. The use of a statin medication should be considered even for patients with mild or moderate hypercholesterolemia 32, with the goal of decreasing the low-density lipoprotein cholesterol value to less than 70 mg/dL 33. Antiplatelet therapy should be started immediately; aspirin is the agent most commonly used. Some evidence shows that the combination of aspirin and clopidogrel may be more effective than aspirin alone when prescribed within 24 hours of a transient ischaemic attack or a minor stroke 34; however, combination therapy is not generally recommended 35, 36. The addition of clopidogrel therapy increases the risk of hemorrhagic complications and might impair hemostasis in patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy. Therefore, the safety of adding clopidogrel to aspirin for patients with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis needs to be confirmed before this combination can be recommended for routine use. The combination of aspirin and extended-release dipyridamole has not been specifically evaluated in patients with acute symptomatic carotid disease. Symptomatic carotid artery stenosis is not an indication for oral anticoagulation. It is also prudent to consider screening these patients with a stress test because of the possibility of concomitant coronary artery disease, even in the absence of angina or other symptoms of myocardial ischemia 37.

In patients with symptomatic carotid artery disease, carotid endarterectomy is effective in preventing future ipsilateral ischemic events, provided that the perioperative combined risk of stroke and death is not higher than 6% 33. Its effect is marked in patients with high-grade (>70%) stenosis, with 8 patients needed to be treated to prevent 1 ipsilateral stroke in a 2-year period 26. The benefit is still present, although less pronounced, in symptomatic patients with a moderate (50%-75%) degree of stenosis, with 20 patients needed to be treated to prevent 1 ipsilateral stroke during a 2-year period 26.

The observation that the risk of ipsilateral stroke is much higher in the first few weeks after a qualifying transient ischaemic attack than it is later has important therapeutic implications. To maximize the benefit of surgery, treatment should be performed on an urgent basis after a transient ischaemic attack. Pooled analysis of the randomized controlled trials suggested that the benefit from carotid endarterectomy was maximal in patients who had the operation within 2 weeks of a qualifying event. In patients with symptomatic stenosis of 70% to 99%, the absolute risk reduction decreased from 23% to 16% and then to 8% when patients were treated within 2 weeks, between 2 and 4 weeks, and after 4 weeks, respectively 38. The decreasing benefit of carotid endarterectomy with increasing time from the qualifying ischemic event was particularly evident in women 39. In fact, the benefit of treatment was lost in women when treatment was delayed more than 2 weeks 39.

Traditionally, surgeons have been reluctant to operate within 1 month of a qualifying transient ischaemic attack or a minor stroke because of a perceived higher risk of periprocedural complications with this timeline than with a later one 40. However, subgroup analysis of the randomized controlled trials showed that the perioperative risks of stroke and death were not increased in patients who underwent an operation within 2 weeks of the qualifying event 39. Recent guidelines for secondary stroke prevention recommend that carotid endarterectomy be performed within 2 weeks for patients presenting with a transient ischaemic attack or minor stroke 33.

Asymptomatic Carotid Artery Stenosis

With the wide availability of various noninvasive diagnostic modalities, most patients who receive a diagnosis of carotid disease are asymptomatic. For many of these patients, intensive medical treatment may be the most appropriate therapeutic option.

Hypertension should be treated to maintain blood pressures consistently below 140/90 mm Hg 41 except for patients with diabetes mellitus or kidney disease, in whom blood pressures should stay below 130/80 mm Hg. Currently, it is unclear whether certain antihypertensive agents may be more effective than others in reducing the progression of carotid atherosclerosis 42; therefore, the presence of comorbid conditions and the cost should guide agent selection.

Lipid-lowering therapy should preferentially include a statin and should aim to achieve a low-density lipoprotein cholesterol value of less than 100 mg/dL. For patients with numerous vascular risk factors or coexistent symptomatic coronary artery disease, a target value of less than 70 mg/dL may be preferable. Smoking cessation is imperative, and any necessary counseling and medical therapies for smoking cessation should be used. Diabetes screening is necessary for all patients with carotid atherosclerosis, and patients with diabetes should be treated.

Patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis should be treated with aspirin. No proof exists of added benefit due to combining aspirin with extended-release dipyridamole or with clopidogrel for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Patients with aspirin allergy should be treated with clopidogrel alone. Aspirin plus clopidogrel is appropriate for patients with concomitant symptomatic coronary artery disease, recent coronary stenting, and severe peripheral arterial disease.

A regular program of aerobic exercise (>30 minutes on 5 or more days per week) should be initiated, along with a diet low in saturated fat, to maintain a body mass index (calculated as the weight in kilograms divided by the height in meters squared) of less than 25 kg/m2 43. In addition, all patients with documented carotid artery disease should be instructed about stroke symptoms (especially but not exclusively symptoms expected in accordance with the side affected by the stenosis) and about the importance of seeking immediate medical attention if symptoms occur.

The decision on whether to implement invasive treatment in patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis is a difficult one. The benefit of carotid endarterectomy in randomized controlled trials was marginal. The 2 largest randomized controlled trials comparing carotid endarterectomy with medical treatment for asymptomatic patients showed that surgery provided only a modest benefit in stroke prevention 44, 45. In these studies, carotid endarterectomy reduced the risk of stroke from 2% per year to 1% per year.

In the analysis of these 2 trials and their conclusions, an important consideration is that the enrolled patients constituted a highly selected group; they are not necessarily representative of patients routinely seen in clinical practice. For example, about 42,000 people were screened in the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study, but only 1662 people with an angiographically confirmed stenosis of 60% or greater were randomly assigned to treatment 45. The medical treatment arm in these randomized controlled trials was not uniformly defined and it did not include interventions currently considered optimal medical management, such as intensive decreases in blood pressure and lipid concentrations. It is unknown whether current standard medical therapy can decrease the relative benefit from carotid endarterectomy in patients with asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis by decreasing the rate of stroke.

Patients with a life expectancy of less than 5 years are unlikely to benefit from the modest risk reduction afforded by surgery 44. In the Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial, surgery did not benefit patients aged 75 years or older because of the excess mortality rate at follow-up in these patients—a rate related to such non-cerebrovascular events as myocardial infarction and cancer 44. With the advent of carotid angioplasty and stenting, which is perceived to be a less invasive treatment, this consideration is particularly important because more patients with severe systemic comorbidities are being considered for carotid revascularization. Surgical team selection is also important to maximize the modest benefit afforded by carotid endarterectomy in asymptomatic disease. In asymptomatic patients with severe carotid artery stenosis, the benefit is only maintained when the perioperative risks of stroke and death are below 3% 45.

Identification of asymptomatic patients who are at increased risk of stroke would improve the yield of prophylactic invasive treatment. Predictors of increased risk of ipsilateral ischemic events in asymptomatic patients with carotid artery stenosis are the following: a stenosis of increased severity 46, a progressive stenosis, a history of contralateral symptomatic carotid artery stenosis,7 and increased serum creatinine concentrations 46. Early reports suggest that detailed imaging may allow identification of carotid plaques that are more likely to cause symptoms. However, these studies are preliminary and require confirmation.

Carotid endarterectomy or stenting ?

The criterion standard for invasive treatment of carotid artery stenosis is carotid endarterectomy. Recently, carotid angioplasty and stenting has been proposed as a valid alternative to carotid endarterectomy. Compared with carotid endarterectomy, carotid angioplasty and stenting has the advantage that it can be done with the patient under mild sedation, requires no incision, carries no risk of cranial nerve palsy, and has fewer cardiovascular complications. Over the years, carotid endarterectomy has been shown to be safe (when done by operators with acceptably low morbidity and mortality outcomes), effective in preventing ipsilateral strokes, and durable (ie, a low incidence of restenosis). For its acceptance as a valid alternative to carotid endarterectomy, carotid angioplasty and stenting must fulfill the same criteria of safety, effectiveness, and durability.

The safety of carotid angioplasty and stenting compared with that of carotid endarterectomy has been studied in randomized controlled trials 47, 48 and in prospective (often industry-sponsored) registries 49. These recent studies have several common features, including prospective data collection, outcome assessment by independent neurologists, and similar end points of myocardial infarction, stroke, and death within 30 days of the procedure. Although the results of these studies are far from resolving the debate on the safety of carotid angioplasty and stenting vs carotid endarterectomy, they have identified high-risk subgroups. It was thought that the carotid angioplasty and stenting procedure, being less invasive than carotid endarterectomy, could be advantageous for older patients. However, paradoxically, subgroup analyses of prospective studies have consistently shown that greater age is associated with a higher risk of periprocedural morbidity and death after carotid angioplasty and stenting but not necessarily after carotid endarterectomy 50, 51, 52. After carotid angioplasty and stenting, symptoms that are recent (within 2 weeks of the procedure) are also associated with increased complication rates 50. Final analysis of larger multicenter, non-industry-sponsored trials comparing carotid angioplasty and stenting with carotid endarterectomy will be available soon. It is hoped that the results of these studies will answer most of the remaining questions regarding the safety and relative value of carotid angioplasty and stenting.

A meta-analysis of published randomized controlled trials indicated that the risk of stroke within 30 days of the intervention was slightly higher in the carotid angioplasty and stenting than the carotid endarterectomy group 48. However, the long-term (2-3 years) effectiveness of carotid angioplasty and stenting in preventing ipsilateral ischemic events is supported by randomized studies showing that the long-term incidence of ipsilateral strokes is not different between carotid angioplasty and stenting and carotid endarterectomy 53, 54, 55. Data on the incidence of restenosis are preliminary, but restenosis rates reported after carotid angioplasty and stenting are relatively low 53, 54. More importantly, most restenoses are asymptomatic and therefore of unclear clinical importance. Moreover, it is likely that restenosis rates may decrease as the stent technology continues to improve.

The recently completed “Carotid Occlusion Surgery Study” 56 failed to show a benefit for extracranial-intracranial bypass among patients with carotid occlusion judged at high risk of recurrent stroke by PET imaging. Patients with sypmtomatic intracranial large vessel stenosis are also known to be at high risk of recurrence. The SAMMPRIS Trial tested intracranial stenting plus medical management vs. medical management alone and was closed early due to high peri-procedural risk of stroke or death in the stenting group 57. In that study 57 patients with intracranial arterial stenosis, aggressive medical management was superior to percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting with the use of the Wingspan stent system, both because the risk of early stroke after percutaneous transluminal angioplasty and stenting was high and because the risk of stroke with aggressive medical therapy alone was lower than expected. Long term follow-up of subjects in SAMMPRIS continues.

While clinicians await the conclusion of the large randomized controlled trials, carotid angioplasty and stenting should be considered for patients with indication for carotid revascularization and high surgical risk. At this time, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services only reimburses the cost of carotid angioplasty and stenting for patients with symptomatic carotid artery stenosis of a severity of at least 70% who are considered high-risk patients for surgery 21. In all other patient categories, the procedure is reimbursed only in the setting of one of the numerous ongoing postmarketing registries or clinical trials.

Carotid artery dissection

Carotid artery dissection means a tear in the lining in one of the main blood vessels carrying blood to the brain. Dissection can be caused by injury to the neck, but can sometimes develop for no obvious reason 58. Blood clots can form where the artery is torn. These blood clots can then block the artery and cause a stroke.

Internal carotid artery dissection is an increasingly recognized cause of stroke that accounts for up to 20% of ischemic strokes in young adults under 30 years of age 59, 60. However, spontaneous internal carotid artery dissections are uncommon 61. In community-based studies in the United States and France, the annual incidence of spontaneous internal carotid artery dissections ranged from 2.5 to 3 per 100,000 62, 63. Spontaneous dissections of the carotid and vertebral arteries affect all age groups, including children; however, internal carotid artery dissections present most commonly in the fifth decade of life 64, 65, 66.

At presentation, on average, women are five years younger than men, although there is no gender predilection 64. Patients with spontaneous dissection of the carotid artery are believed to have an underlying structural defect of the arterial wall, albeit the exact type of arteriopathy remains elusive in most cases. Among the heritable connective tissue disorders associated with an increased risk of spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection, Ehlers-Danlos syndrome type IV is most common 67. Others include Marfan’s syndrome, autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease, and osteogenesis imperfecta type I 67, 68. Minor events such as hyperextension or rotation of the neck while practicing yoga, painting a ceiling, coughing, vomiting, or sneezing have all been reported to precipitate internal carotid artery dissection. Chiropractic manipulation of the neck has also been associated with internal carotid artery dissection 69. Additionally, infections such as purulent tonsillitis, purulent and nonpurulent pharyngitis, otitis media and sinusitis have also been described as potential risk factors 70. It may also occur during intubations for general anesthesia or cardiopulmonary resuscitation 65, 71, 72. Mechanical ventilation as a direct cause of internal carotid artery dissection has not been reported in the literature. Most cases of internal carotid artery dissections present within hours; however, some develop over weeks as evolving symptoms leading patients to seek medical attention 73.

Symptoms of internal carotid artery dissection include 74, 75, 76:

- headache,

- anterior neck pain,

- scalp tenderness,

- transient ischemic attack,

- cerebral infarction,

- amaurosis fugax,

- cranial nerve palsies,

- tinnitus and Horner’s syndrome.

Sturzenegger et al. 77 reported 44 patients with spontaneous internal carotid artery dissection with symptoms including unilateral headache (68%), transient ischemic attack (20%) and cerebral infarction (9%).

Table 2. Most common presenting symptoms of internal carotid artery dissection (in descending order)

| Symptom | Reported Frequency | Character |

|---|---|---|

| Headache and neck pain | >90% | Typically severe and of sudden onset, affecting the ispsilateral periorbital, fontal, or upper cervical region. |

| Often unique, or of different character than previously experienced. | ||

| Ischemic symptoms | 50–95% | Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) or stroke. |

| Horner’s Syndrome | <52% | Incomplete, lacking anhydrosis. May be painful. |

| Visual scintillations | 33% | Episodic |

| Monocular blindness | 6–30% | Transient |

| Subjective bruit | 25–48% | May also manifest as a pulsatile tinnitus. |

| Dysgeusia | 10–19% | Impairment of taste. |

Ipsilateral cranial nerve palsies have been reported in association with internal carotid artery dissection22. This case report serves to remind us to consider the diagnosis of internal carotid artery dissection in patients presenting with isolated hypoglossal nerve palsy. Mokri et al. 76 described a prevalence of 12% of cranial nerve palsies in their study of 190 adult patients with spontaneous extracranial internal carotid artery dissection. Those with lower cranial nerve palsies (5.2%) included variable involvement of the hypoglossal nerve along with cranial nerve IX, X and XI, and only one case with an isolated hypoglossal nerve palsy. More common cranial nerve palsies included cranial nerve V (3.7%) and cranial nerve III (3.6%) 76. The mechanism of cranial nerve palsy in internal carotid artery dissection has been theorized to be secondary to compression or stretching of the nerve by the expanded artery. An alternative mechanism is likely interruption of the nutrient vessels supplying the nerve 76.

According to a common view, internal carotid artery dissection leads to embolic rather than to hemodynamic cerebral infarction 79. However, systematic investigations of the underlying mechanism of cerebral ischemia have rarely been performed 80, 81. The presumed mechanism of stroke may be approached by determining the stroke pattern in patients with internal carotid artery dissection. Two previous studies 80, 81, found conflicting results: one suggested a prominent hemodynamic compromise in internal carotid artery dissection 82 and the other suggested a prominent embolic mechanism 81. Determining whether most internal carotid artery dissections lead to cerebral ischemia because of artery-to-artery embolism or because of hemodynamic failure is valuable, because it may influence the therapeutic approach: heparin may be more appropriate in the first mechanism but is not likely to be effective in the second, and it might even lead to an increase of the mural hematoma. Because of the low rate of recurrence of cerebral ischemia in patients with carotid artery dissection, a drug trial remains difficult 83. Therefore, the therapeutic approach should be based on the presumed mechanism of cerebral ischemia in patients with carotid artery dissection.

This study 84 showed that most infarcts related to internal carotid artery dissection are cortical or large subcortical infarcts. Epidemiological and clinical data are similar to these of the literature 83, 85. According to the current conception of the relationship between the mechanism of infarction and stroke patterns, cortical or subcortical infarcts are more likely to be of embolic origin 86, 87, 88, whereas junctional or watershed infarcts are more likely to be of hemodynamic origin 89. Using this simplification, researchers found that only 7.7% of patients with carotid artery dissection had a presumed hemodynamic cerebral ischemia, whereas 92.2% had a presumed embolic infarct. A thrombus formation in the dissected artery with secondary distal embolism is the most likely mechanism of cerebral infarction in carotid artery dissection.

Systemic anticoagulation remains the treatment of choice for internal carotid artery dissections. Initial therapy includes intravenous heparin with concomitant institution of oral warfarin for conversion to long term oral therapy. The target international normalized ratio is maintained between 1.5 to 2.5 90, 91, 92. In patients with progressive neurologic deficits, endovascular stenting and balloon dilatation are successful alternatives to surgical therapy, which if needed consists of ligation of the carotid artery combined with an in-situ or extracranial-to-intracranial bypass 93, 94. Spontaneous internal carotid artery dissections usually have a favorable prognosis, with approximately 90% of cases resolving without serious sequelae. Spontaneous recanalization of the internal carotid artery is reported in over two thirds of patients with a recurrence rate of less than 10% 91.

Lastly, this 2010 Cochrane Review 58 reported there were no randomised trials comparing either anticoagulants or antiplatelet drugs with control, thus there is no evidence to support their routine use for the treatment of extracranial internal carotid artery dissection. There were also no randomised trials that directly compared anticoagulants with antiplatelet drugs and the reported non-randomised studies did not show any evidence of a significant difference between the two. Blood thinning drugs such as aspirin and anticoagulants might prevent clots forming and so prevent stroke in people with carotid artery dissection. The authors found no evidence that anticoagulants were better than aspirin. Aspirin is likely to be similarly effective and safe as anticoagulants in such patients 58. However more research is needed.

- National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Carotid Artery Disease. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/catd[↩]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Medline Plus. Atherosclerosis. https://medlineplus.gov/atherosclerosis.html[↩]

- Louridas G, Junaid A. Management of carotid artery stenosis: Update for family physicians. Canadian Family Physician. 2005;51(7):984-989. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1479527/[↩]

- National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. What Causes Carotid Artery Disease ? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/catd/causes[↩]

- National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Who Is at Risk for Carotid Artery Disease ? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/catd/atrisk[↩]

- National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. What Are the Signs and Symptoms of Carotid Artery Disease ? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/catd/signs[↩]

- National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. How Is Carotid Artery Disease Diagnosed ? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/catd/diagnosis[↩]

- National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. How Is Carotid Artery Disease Treated ? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/catd/treatment[↩][↩][↩]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Medline Plus. Carotid artery surgery. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002951.htm[↩][↩][↩]

- National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. Carotid Endarterectomy. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/carend[↩][↩]

- U.S. National Library of Medicine. Medline Plus. Angioplasty and stent placement – carotid artery. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/002953.htm[↩][↩]

- National Institutes of Health. National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. How Can Carotid Artery Disease Be Prevented ? https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/health-topics/topics/catd/prevention[↩]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Carotid Artery Stenosis as a Cause of Stroke. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/33541[↩]

- Petty GW, Brown RD Jr, Whisnant JP, et al. Ischemic stroke subtypes: A population-based study of incidence and risk factors. Stroke. 1999; 30:2513–2516.[↩]

- Uchino K, Risser JMH, Smith MA, et al. Ischemic stroke subtypes among Mexican Americans and non- Hispanic whites: The BASIC project. Neurology. 2004; 63:574–576.[↩]

- Schneider AT, Kissela B, Woo D, et al. Ischemic stroke subtypes: A population-based study of incidence rates among blacks and whites. Stroke. 2004; 35:1552–1556.[↩]

- Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, et al. for the Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists’ Collaboration. Analysis of pooled data from the randomised controlled trials of endarterectomy for symptomatic carotid stenosis. Lancet. 2003; 361:107–116.[↩]

- Carotid Artery Stenosis as a Cause of Stroke. Neuroepidemiology . 2013 ; 40(1): 36–41. doi:10.1159/000341410. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/33541[↩][↩]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/carotid-artery-stenosis-screening[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Home/GetFileByID/1879[↩]

- Lanzino G, Rabinstein AA, Brown RD. Treatment of Carotid Artery Stenosis: Medical Therapy, Surgery, or Stenting? Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2009;84(4):362-368. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2665982/[↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Carotid bruits as a prognostic indicator of cardiovascular death and myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis. Pickett CA, Jackson JL, Hemann BA, Atwood JE. Lancet. 2008 May 10; 371(9624):1587-94. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18468542/[↩][↩][↩]

- Symptomatic carotid ischaemic events: safest and most cost effective way of selecting patients for angiography, before carotid endarterectomy. Hankey GJ, Warlow CP. BMJ. 1990 Jun 9; 300(6738):1485-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1663209/[↩][↩]

- Duplex ultrasound and magnetic resonance angiography compared with digital subtraction angiography in carotid artery stenosis: a systematic review. Nederkoorn PJ, van der Graaf Y, Hunink MG. Stroke. 2003 May; 34(5):1324-32. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12690221/[↩]

- Evaluation of transient ischemic attack in an emergency department observation unit. Stead LG, Bellolio MF, Suravaram S, Brown RD Jr, Bhagra A, Gilmore RM, Boie ET, Decker WW. Neurocrit Care. 2009; 10(2):204-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18850077/[↩][↩]

- Benefit of carotid endarterectomy in patients with symptomatic moderate or severe stenosis. North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy Trial Collaborators. Barnett HJ, Taylor DW, Eliasziw M, Fox AJ, Ferguson GG, Haynes RB, Rankin RN, Clagett GP, Hachinski VC, Sackett DL, Thorpe KE, Meldrum HE, Spence JD. N Engl J Med. 1998 Nov 12; 339(20):1415-25. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199811123392002[↩][↩][↩]

- Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial. Halliday A, Mansfield A, Marro J, Peto C, Peto R, Potter J, Thomas D, MRC Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST) Collaborative Group. Lancet. 2004 May 8; 363(9420):1491-502. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15135594/[↩]

- Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study. JAMA. 1995 May 10; 273(18):1421-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7723155/[↩]

- Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, Marquardt L, Geraghty O, Redgrave JN, Lovelock CE, Binney LE, Bull LM, Cuthbertson FC, Welch SJ, Bosch S, Alexander FC, Silver LE, Gutnikov SA, Mehta Z, Early use of Existing Preventive Strategies for Stroke (EXPRESS) study. Lancet. 2007 Oct 20; 370(9596):1432-42. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17928046/[↩][↩][↩]

- Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, Giles MF, Elkins JS, Bernstein AL, Sidney S. Lancet. 2007 Jan 27; 369(9558):283-92. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17258668/[↩][↩]

- Relationship between blood pressure and stroke risk in patients with symptomatic carotid occlusive disease. Rothwell PM, Howard SC, Spence JD, Carotid Endarterectomy Trialists’ Collaboration. Stroke. 2003 Nov; 34(11):2583-90. http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/34/11/2583.long[↩]

- High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A 3rd, Goldstein LB, Hennerici M, Rudolph AE, Sillesen H, Simunovic L, Szarek M, Welch KM, Zivin JA, Stroke Prevention by Aggressive Reduction in Cholesterol Levels (SPARCL) Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2006 Aug 10; 355(6):549-59. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa061894[↩]

- Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention: the American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this guideline. Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, Alberts MJ, Benavente O, Furie K, Goldstein LB, Gorelick P, Halperin J, Harbaugh R, Johnston SC, Katzan I, Kelly-Hayes M, Kenton EJ, Marks M, Schwamm LH, Tomsick T, American Heart Association., American Stroke Association Council on Stroke., Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention., American Academy of Neurology. Stroke. 2006 Feb; 37(2):577-617. http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/37/2/577.long[↩][↩][↩]

- Fast assessment of stroke and transient ischaemic attack to prevent early recurrence (FASTER): a randomised controlled pilot trial. Kennedy J, Hill MD, Ryckborst KJ, Eliasziw M, Demchuk AM, Buchan AM, FASTER Investigators. Lancet Neurol. 2007 Nov; 6(11):961-9. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17931979/[↩]

- Clopidogrel and aspirin versus aspirin alone for the prevention of atherothrombotic events. Bhatt DL, Fox KA, Hacke W, Berger PB, Black HR, Boden WE, Cacoub P, Cohen EA, Creager MA, Easton JD, Flather MD, Haffner SM, Hamm CW, Hankey GJ, Johnston SC, Mak KH, Mas JL, Montalescot G, Pearson TA, Steg PG, Steinhubl SR, Weber MA, Brennan DM, Fabry-Ribaudo L, Booth J, Topol EJ, CHARISMA Investigators. N Engl J Med. 2006 Apr 20; 354(16):1706-17. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa060989[↩]

- Aspirin and clopidogrel compared with clopidogrel alone after recent ischaemic stroke or transient ischaemic attack in high-risk patients (MATCH): randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Diener HC, Bogousslavsky J, Brass LM, Cimminiello C, Csiba L, Kaste M, Leys D, Matias-Guiu J, Rupprecht HJ, MATCH investigators. Lancet. 2004 Jul 24-30; 364(9431):331-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15276392/[↩]

- Coronary risk evaluation in patients with transient ischemic attack and ischemic stroke: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the Stroke Council and the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Adams RJ, Chimowitz MI, Alpert JS, Awad IA, Cerqueria MD, Fayad P, Taubert KA, Stroke Council and the Council on Clinical Cardiology of the American Heart Association., American Stroke Association. Circulation. 2003 Sep 9; 108(10):1278-90. http://circ.ahajournals.org/content/108/10/1278.long[↩]

- Delay may reduce procedural risk, but at what price to the patient ? Naylor AR. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008 Apr; 35(4):383-91. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18261942/[↩]

- Sex difference in the effect of time from symptoms to surgery on benefit from carotid endarterectomy for transient ischemic attack and nondisabling stroke. Rothwell PM, Eliasziw M, Gutnikov SA, Warlow CP, Barnett HJ. Stroke. 2004 Dec; 35(12):2855-61. http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/35/12/2855.long[↩][↩][↩]

- Delay may reduce procedural risk, but at what price to the patient ? Naylor AR. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2008 Apr; 35(4):383-91. http://www.ejves.com/article/S1078-5884(08)00010-5/fulltext[↩]

- Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, et al. National High Blood Pressure Education Program Coordinating Committee The seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure: the JNC 7 report [published correction appears in JAMA. 2003;290(2):197] JAMA 2003May;289(19):2560-2572 Epub 2003 May 14. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12748199[↩]

- Daskalopoulou SS, Daskalopoulos ME, Perrea D, Nicolaides AN, Liapis CD. Carotid artery atherosclerosis: what is the evidence for drug action? Curr Pharm Des. 2007;13(11):1141-1159. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17430176[↩]

- Sacco RL, Adams R, Albers G, et al. Guidelines for prevention of stroke in patients with ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Council on Stroke: co-sponsored by the Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention Stroke 2006;37(2):577-617. http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/37/2/577.long[↩]

- MRC Asymptomatic Carotid Surgery Trial (ACST) Collaborative Group Prevention of disabling and fatal strokes by successful carotid endarterectomy in patients without recent neurological symptoms: randomised controlled trial [published correction appears in Lancet. 2004;364(9432):416] Lancet 2004;363(9420):1491-1502. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15135594[↩][↩][↩]

- Executive Committee for the Asymptomatic Carotid Atherosclerosis Study Endarterectomy for asymptomatic carotid artery stenosis. JAMA 1995;273(18):1421-1428. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7723155[↩][↩][↩]

- Nicolaides AN, Kakkos SK, Griffin M, et al. Asymptomatic Carotid Stenosis and Risk of Stroke (ACSRS) Study Group Severity of asymptomatic carotid stenosis and risk of ipsilateral hemispheric ischaemic events: results from the ACSRS study. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 2005;30(3):275-284. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/16130207[↩][↩]

- Meschia JF, Brott TG, Hobson RW., II Diagnosis and invasive management of carotid atherosclerotic stenosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2007;82(7):851-858. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17605967[↩]

- Murad MH, Flynn DN, Elamin MB, et al. Endarterectomy vs stenting for carotid artery stenosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(2):487-493. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18644495[↩][↩]

- Goodney PP, Powell RJ. Carotid artery stenting: what have we learned from the clinical trials and registries and where do we go from here? Ann Vasc Surg. 2008;22(1):148-158. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18082918[↩]

- Gray WA, Yadav JS, Verta P, et al. CAPTURE Trial Collaborators The CAPTURE registry: predictors of outcomes in carotid artery stenting with embolic protection for high surgical risk patients in the early post-approval setting. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2007;70(7):1025-1033. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18044758[↩][↩]

- Hobson RW, II, Howard VJ, Roubin GS, et al. CREST Investigators Carotid artery stenting is associated with increased complications in octogenarians: 30-day stroke and death rates in the CREST lead-in phase. J Vasc Surg. 2004;40(6):1106-1111. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15622363[↩]

- Stingele R, Berger J, Alfke K, et al. SPACE investigators Clinical and angiographic risk factors for stroke and death within 30 days after carotid endarterectomy and stent-protected angioplasty: a subanalysis of the SPACE study. Lancet Neurol. 2008March;7(3):216-222 Epub 2008 Jan 31. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18242141[↩]

- Eckstein HH, Ringleb P, Allenberg JR, et al. Results of the Stent-Protected Angioplasty versus Carotid Endarterectomy (SPACE) study to treat symptomatic stenoses at 2 years: a multinational, prospective, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008October;7(10):893-902 Epub 2008 Sep 5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18774746[↩][↩]

- Gurm HS, Yadav JS, Fayad P, et al. SAPPHIRE Investigators Long-term results of carotid stenting versus endarterectomy in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med. 2008;358(15):1572-1579. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMoa0708028[↩][↩]

- Mas JL, Trinquart L, Leys D, et al. EVA-3S Investigators Endarterectomy Versus Angioplasty in Patients with Symptomatic Severe Carotid Stenosis (EVA-3S) trial: results up to 4 years from a randomised, multicentre trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7(10):885-892 Epub 2008 Sep 5. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18774745[↩]

- Powers WJ, Clarke WR, Grubb RL, Videen TO, Adams HP, Derdeyn CP. Extracranial-Intracranial Bypass Surgery for Stroke Prevention in Hemodynamic Cerebral Ischemia: The Carotid Occlusion Surgery Study: A Randomized Trial. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2011;306(18):1983-1992. doi:10.1001/jama.2011.1610. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3601825/[↩]

- Chimowitz MI, Lynn MJ, Derdeyn CP, et al. Stenting versus Aggressive Medical Therapy for Intracranial Arterial Stenosis. The New England journal of medicine. 2011;365(11):993-1003. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1105335. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3552515/[↩][↩]

- Lyrer P, Engelter S. Antithrombotic drugs for carotid artery dissection. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2010, Issue 10. Art. No.: CD000255. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD000255.pub2. http://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/14651858.CD000255.pub2/full[↩][↩][↩]

- Bogousslavsky J, Pierre P. Ischemic stroke in patients under age 45. Neurol Clin. 1992;10:113–124. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/1556998[↩]

- Bogousslavsky J, Regli F. Ischemic stroke in adults younger than 30 years of age: cause and prognosis. Arch Neurol. 1987;44:479–482. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3579657[↩]

- Kaushik S, Abhishek K, Sofi U. Spontaneous Dissection of Internal Carotid Artery Masquerading as Angioedema. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;24(1):126-128. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0813-8. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2607512/[↩]

- Schievink WI, Mokri B, Whisnant JP. Internal carotid artery dissection in a community: Rochester, Minnesota, 1987–1992. Stroke. 1993;24:1678–80. http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/24/11/1678.long[↩]

- Giroud M, Fayolle H, Andre N, et al. Incidence of internal carotid artery dissection in the community of Dijon. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1994;57:1443. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1073215/pdf/jnnpsyc00041-0141.pdf[↩]

- Schievink WI, Mokri B, O’Fallon WM. Recurrent spontaneous cervical-artery dissection. N Eng J Med. 1994;330:393–7. http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJM199402103300604[↩][↩]

- Leys D, Moulin TH, Stojkovic T, Begey S, Chavot D, DONALD Investigators. Follow-up of patients with history of cervical artery dissection. Cerebrovasc Disease. 1995;5:43–9.[↩][↩]

- Bassetti C, Carruzzo A, Sturzenegger M, Tuncdogan E. Recurrence of cervical artery dissection: a prospective study of 81 patients. Stroke. 1996;27:1804–7. http://stroke.ahajournals.org/content/27/10/1804.long[↩]

- Schievink WI, Michels VV, Piepgras DG. Neurovascular manifestations of heritable connective tissue disorders: a review. Stroke. 1994;25:889–903. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/8160237[↩][↩]