Cervical insufficiency

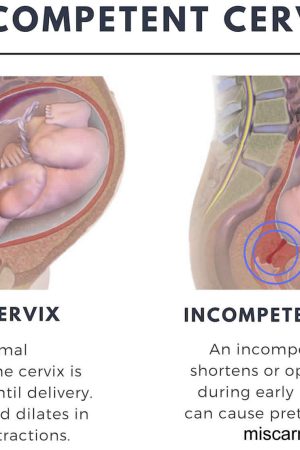

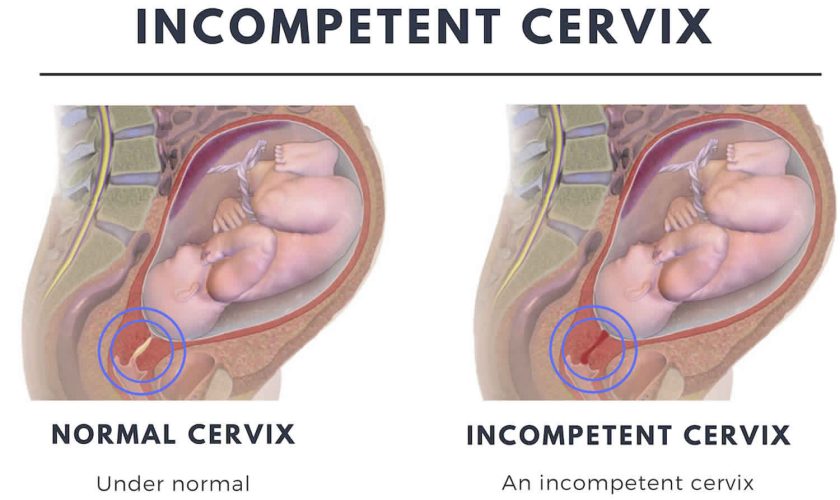

Cervical insufficiency also known as incompetent cervix or weakened cervix, means your cervix opens (dilates) too early during pregnancy, usually without pain or contractions (painless cervical dilatation). Cervical insufficiency or cervical incompetence is the inability of the uterine cervix to retain a pregnancy in the second trimester. Cervical insufficiency can cause premature birth and miscarriage. Premature birth is when your baby is born too early, before 37 weeks of pregnancy. Miscarriage is when a baby dies in the womb before 20 weeks of pregnancy.

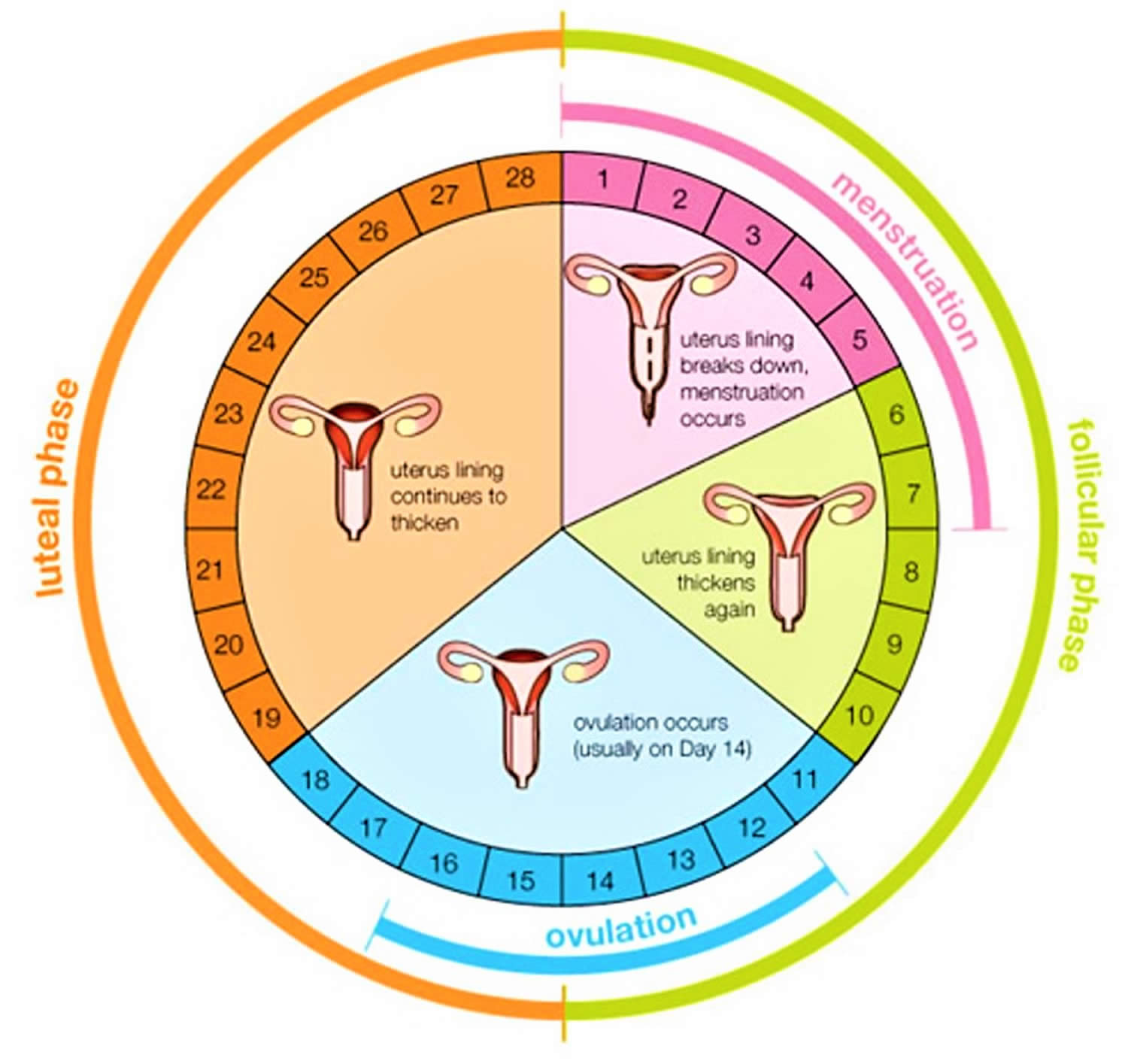

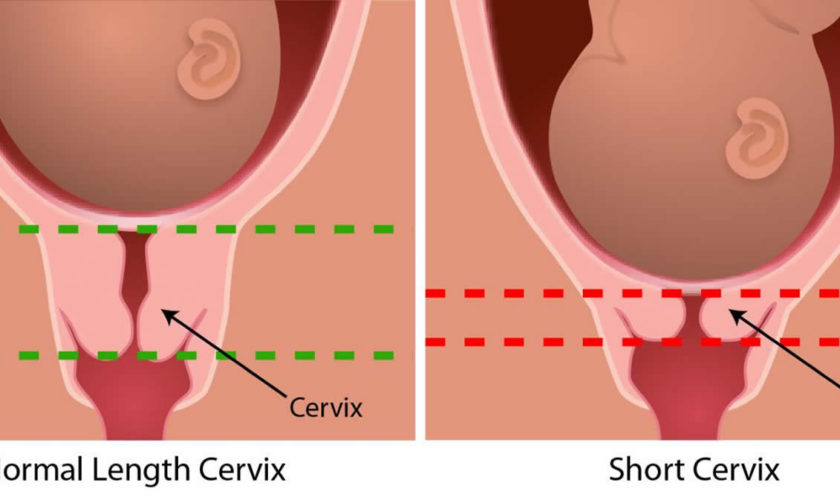

In a normal pregnancy, the cervix stays firm, long, and closed until late in the 3rd trimester. In the 3rd trimester, the cervix starts to soften, get shorter, and open up (dilate) as a woman’s body prepares for labor.

A cervical insufficiency may begin to dilate too early in pregnancy. If there is an cervical incompetence, the following problems are more likely to occur:

- Miscarriage in the 2nd trimester

- Labor begins too early, before 37 weeks

- Bag of waters breaks before 37 weeks

- A premature (early) delivery

When you are told that you have an incompetent cervix, it simply means that your cervix begins to open up (dilates) too early during pregnancy, when you are between four and six weeks of your pregnancy. In case you do not know, the cervix mostly remains closed during the 9 months of pregnancy. An incompetent cervix can be thin and widen without any contractions or pain. This causes the amniotic fluid sac to bulge downwards into the cervix opening until it breaks. This leads to premature delivery or miscarriage. Contractions are when the muscles of your uterus get tight and then relax. They help push your baby out of your uterus during labor and birth.

An incompetent or weakened cervix happens in about 1-2% of pregnancies. Almost 25% of babies miscarried in the second trimester are due to incompetent cervix.

Doctors don’t always know why incompetent cervix happens. You’re more likely than other women to have it if:

- You have defects in your uterus, like if it’s split into two sections.

- You’ve had surgery on your cervix.

- You have a short cervix. The shorter the cervix, the more likely you are to have cervical insufficiency.

- You’ve had injuries to your uterus that happened during a previous birth.

A cervical incompetence or cervical insufficiency, can be treated with an operation to put a small stitch of strong thread around your cervix to keep it closed.

This is usually carried out after the first 12 weeks of your pregnancy.

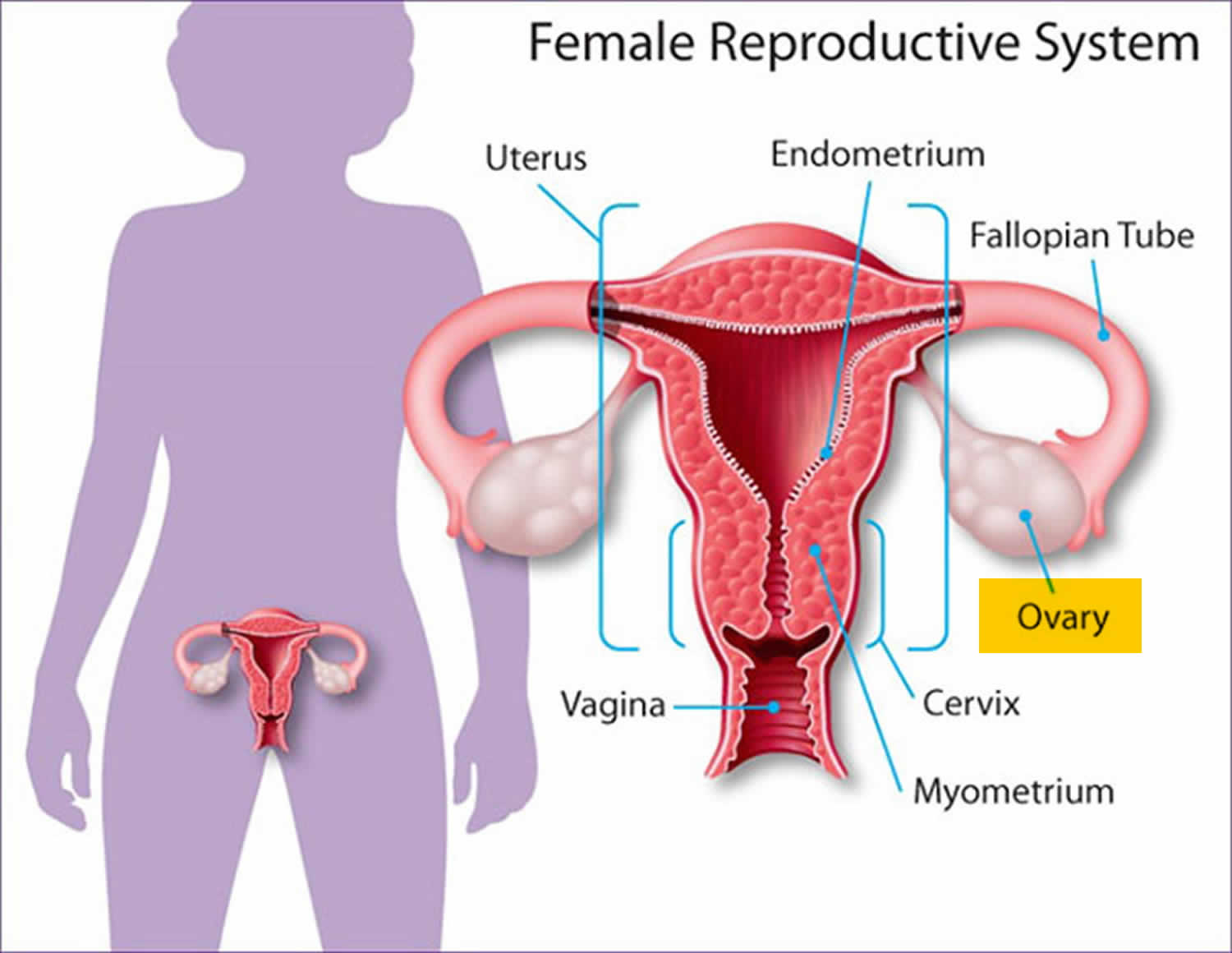

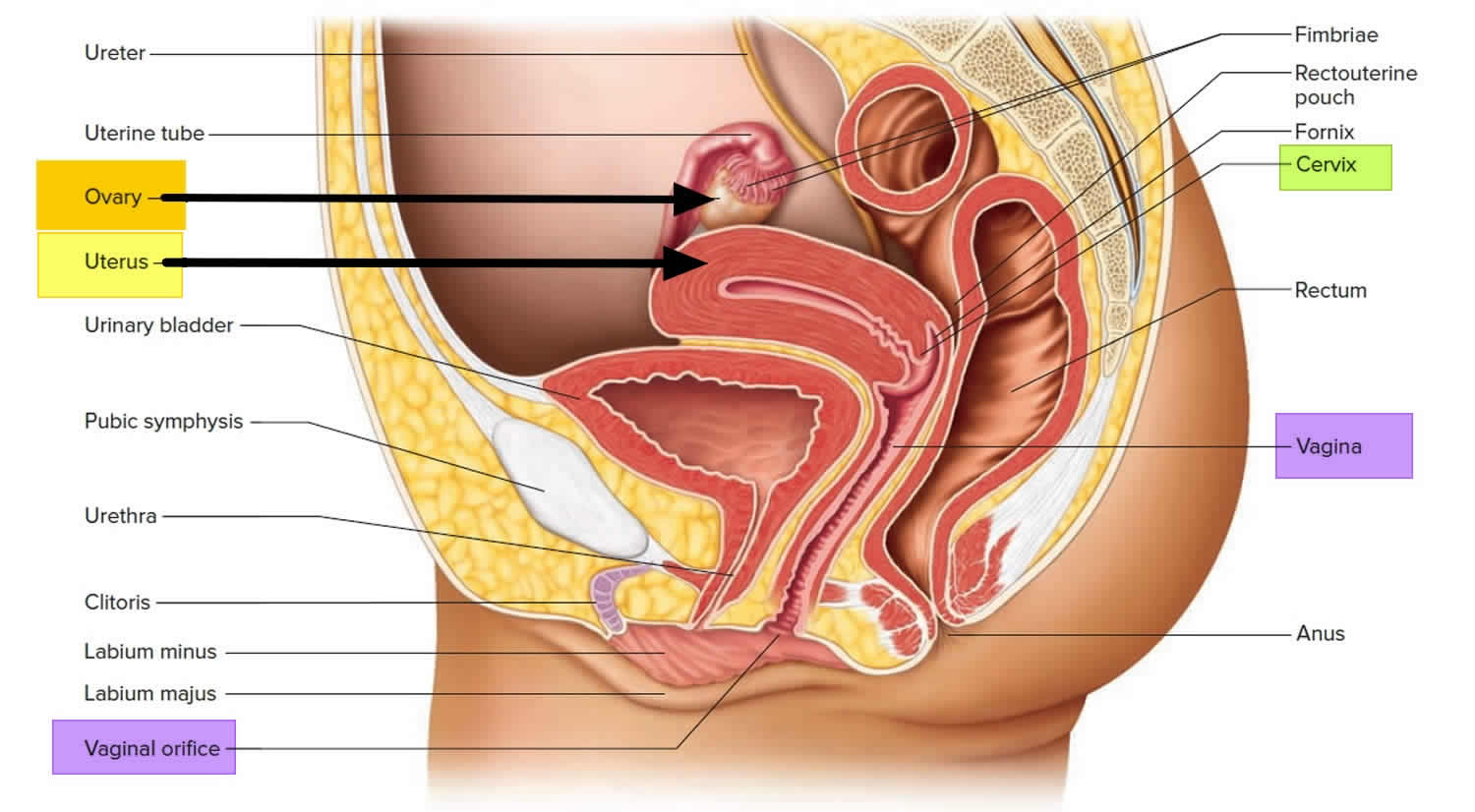

What is a cervix

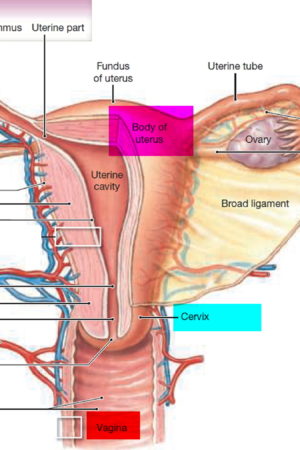

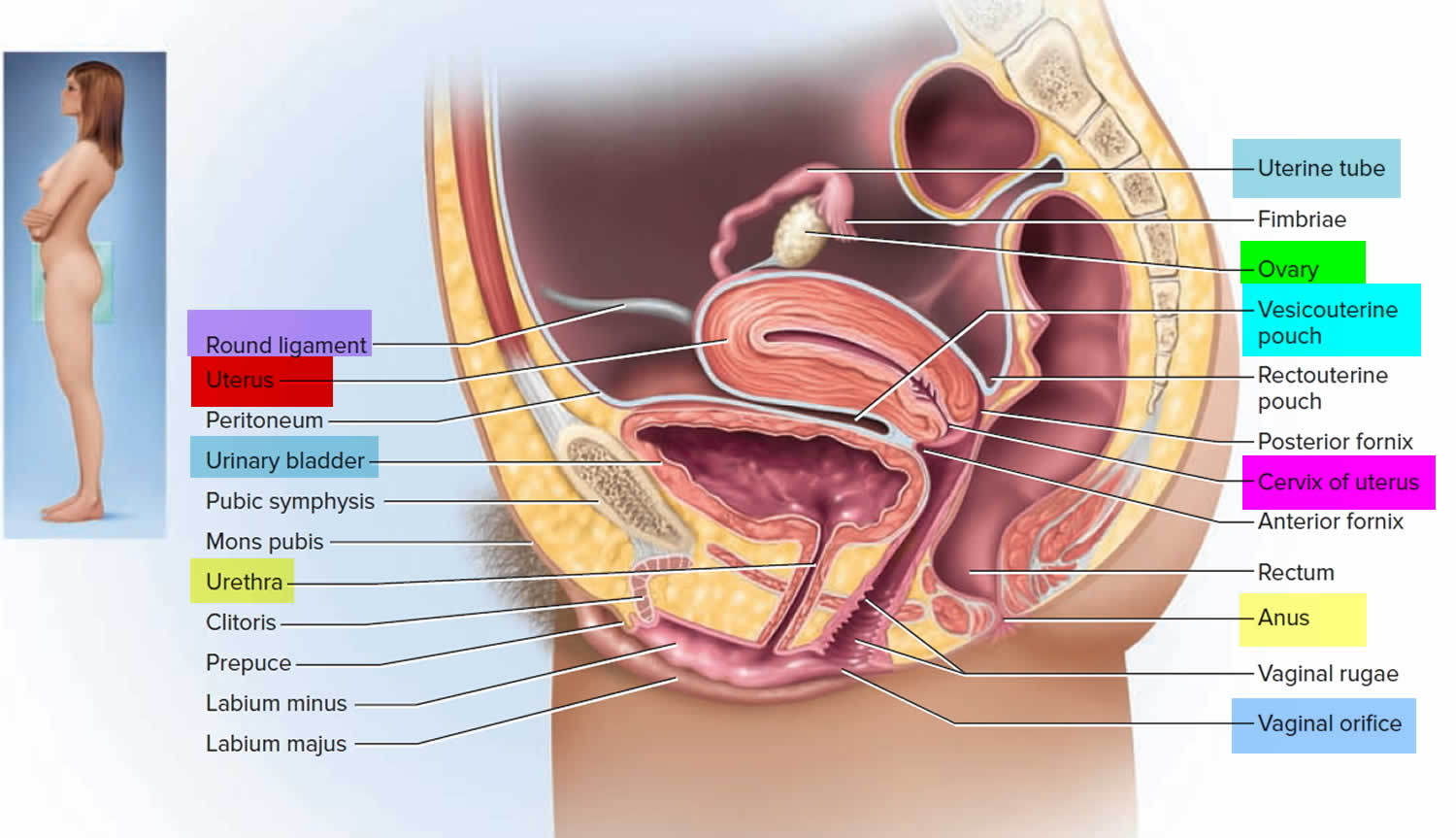

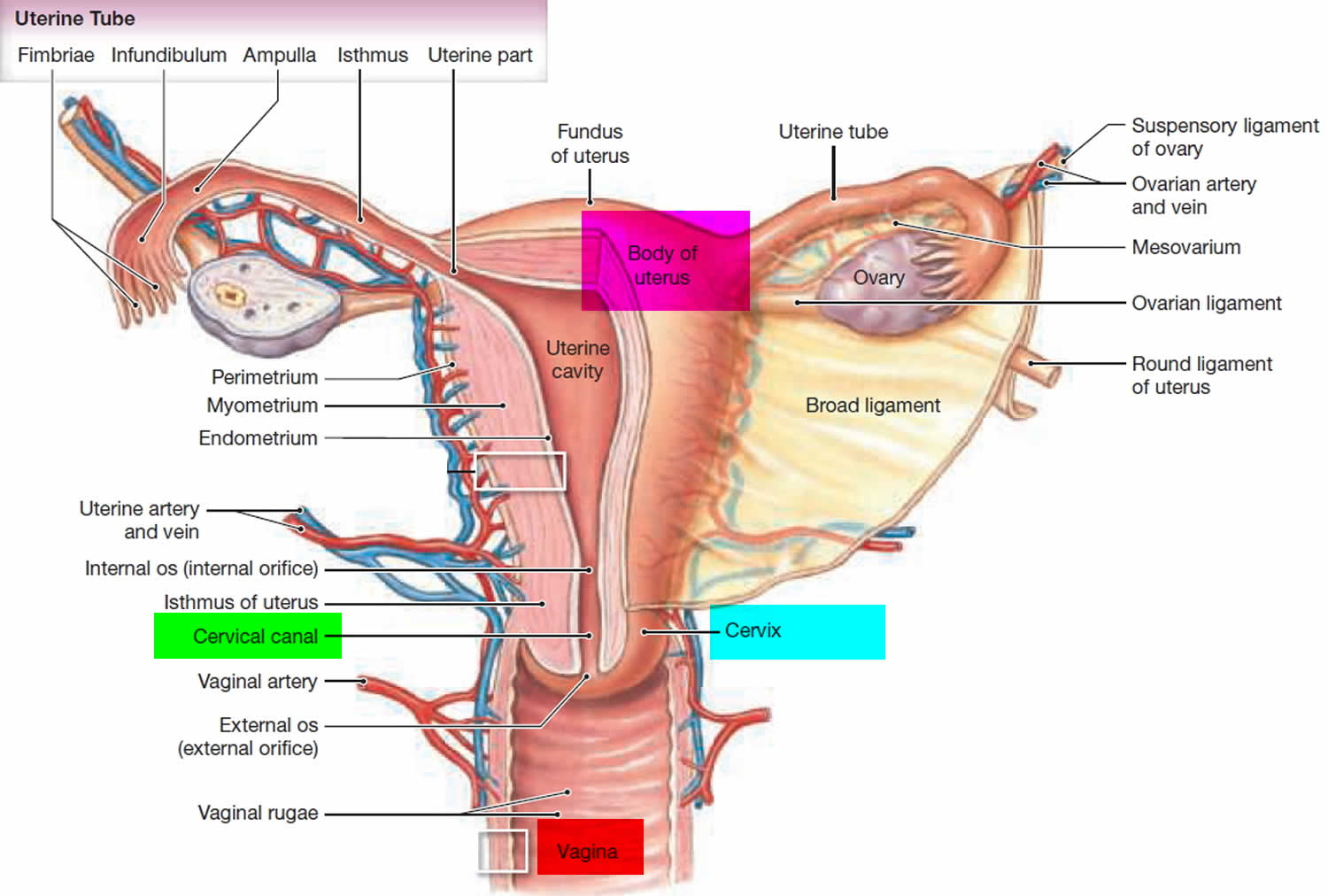

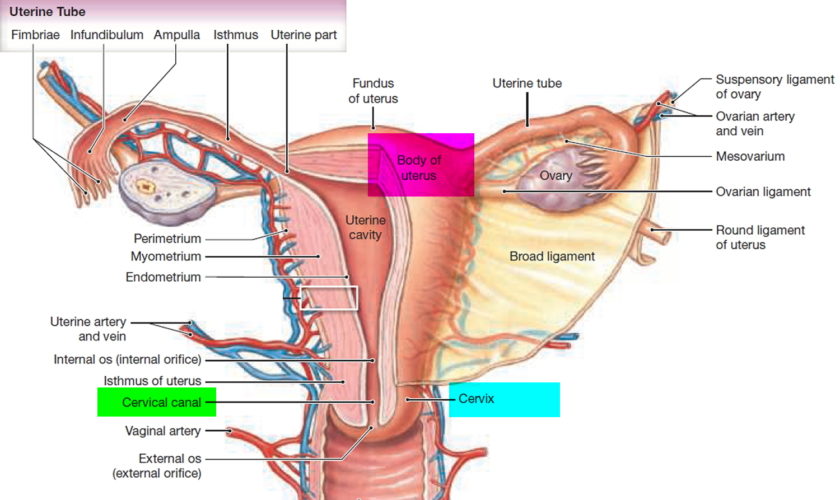

The cervix is the opening in the lower part of the uterus (womb) that opens to the top of the vagina (birth canal). The lumen (internal cavity) of the uterus communicates with the vagina by way of a narrow passage through the cervix called the cervical canal.

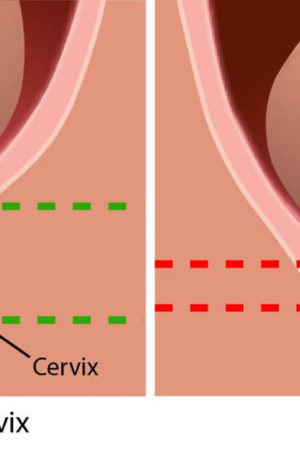

During pregnancy, the cervix stays firm and closed until late in the third trimester. It opens, shortens and gets thinner and softer so your baby can pass through the birth canal during labor and birth. In some women, the cervix opens too early during pregnancy or is shorter than normal. These conditions can cause problems during pregnancy.

Cervix function

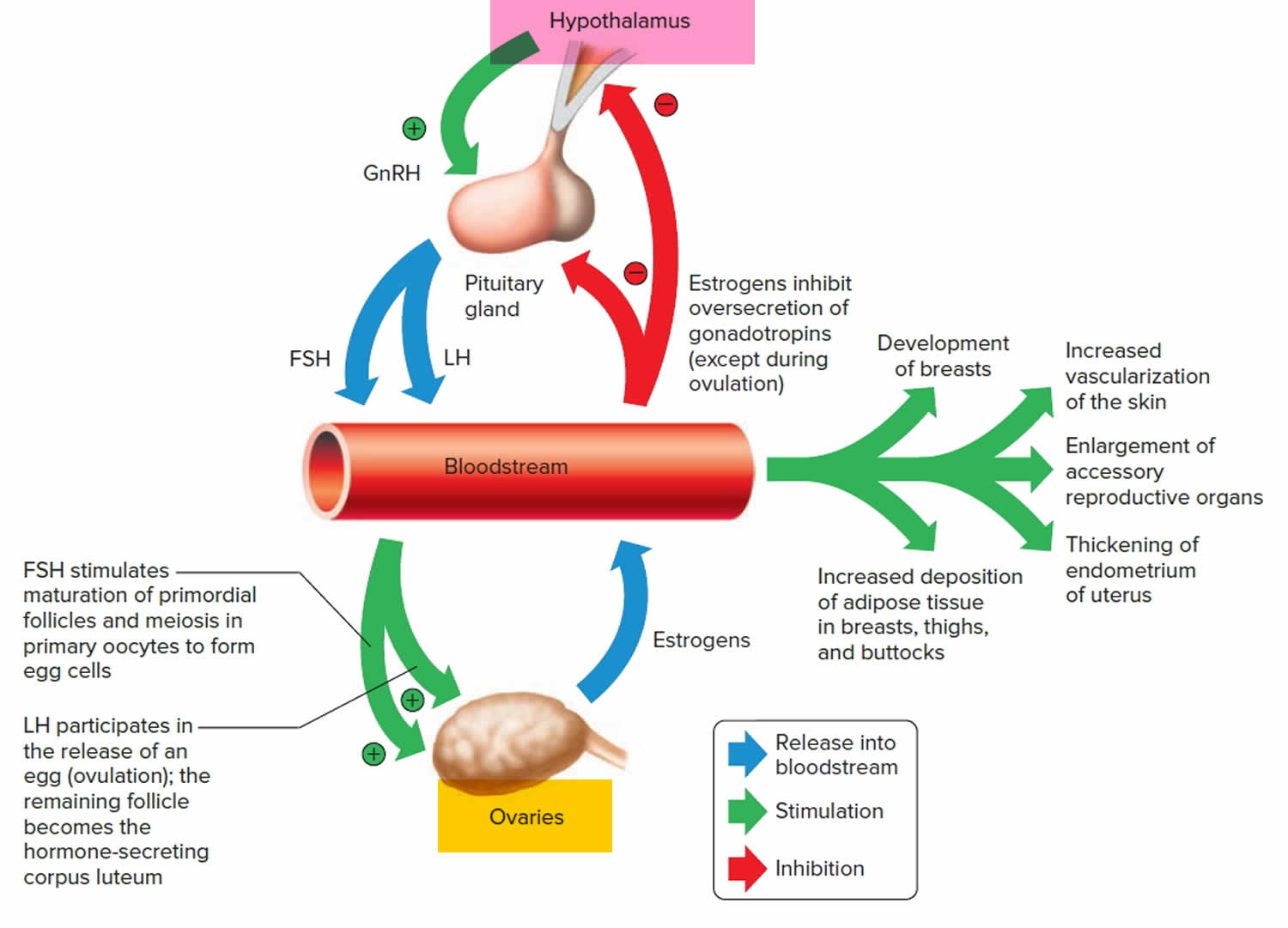

The cervical canal contains cervical glands that secrete mucus, thought to prevent the spread of microorganisms from the vagina into the uterus. Near the time of ovulation, the mucus becomes thinner than usual and allows easier passage for sperm.

The cervix has two different parts and is covered with two different types of cells.

- The part of the cervix closest to the body of the uterus is called the endocervix and is covered with glandular cells.

- The part next to the vagina is the exocervix (or ectocervix) and is covered in squamous cells.

These two cell types meet at a place called the transformation zone. The exact location of the transformation zone changes as you get older and if you give birth.

The cervix and superior part of the vagina are supported by cardinal (lateral cervical) ligaments extending to the pelvic wall.

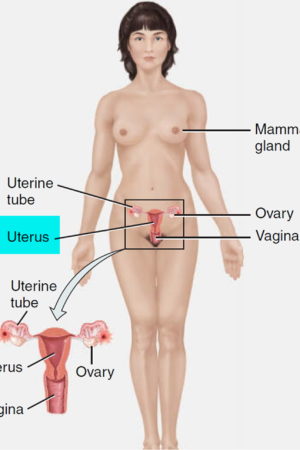

Figure 1. Cervix position

Figure 2. Cervix location

Causes of cervical incompetence

Cervical incompetence may be congenital or acquired 1. The most common congenital cause is a defect in the embryological development of Mullerian ducts. In Ehlers-Danlos syndrome or Marfan syndrome, due to the deficiency in collagen, the cervix is not able to perform adequately, leading to insufficiency.

The most common acquired cause is cervical trauma such as cervical lacerations during childbirth, cervical conization, LEEP (loop electrosurgical excision procedure), or forced cervical dilatation during the uterine evacuation in the first or second trimester of pregnancy.

However, in most patients, cervical changes are the result of infection/inflammation, which causes early activation of the final pathway of parturition 2.

Doctors don’t always know why incompetent cervix happens. You’re more likely than other women to have it if:

- You have defects in your uterus, like if it’s split into two sections.

- You’re pregnant with more than 1 baby like twins or triplets

- You’ve had surgery on your cervix.

- You have a short cervix. The shorter the cervix, the more likely you are to have cervical insufficiency.

- You’ve had injuries to your uterus that happened during a previous birth.

The competent human cervix is a complex organ that undergoes extensive changes throughout gestation and parturition. A complex remodeling process of the cervix occurs during gestation, involving timed biochemical cascades, interactions between the extracellular and cellular compartments, and cervical stromal infiltration by inflammatory cells. Any disarray in this timed interaction could result in early cervical ripening, cervical insufficiency, and preterm birth or miscarriage. Current evidence suggests that cervical incompetence functions along with a continuum that is influenced by both endogenous and exogenous factors, such as uterine contraction and decidual/membrane activation 3.

Cervical insufficiency risk factors

No one knows for sure what causes ancervical insufficiency, but these things may increase a woman’s risk:

- Being pregnant with more than 1 baby (twins, triplets)

- Having a cervical insufficiency in an earlier pregnancy

- Having a torn cervix from an earlier birth

- Having past miscarriages by the 4th month

- Having past first or second semester abortions

- Having a cervix that did not develop normally

- Having a cone biopsy or loop electrosurgical excision procedure (LEEP) on the cervix in the past due to an abnormal Pap smear

Cervical insufficiency symptoms

If your have an incompetent cervix, you may not develop any symptoms or signs early on in pregnancy. Your cervix simply begins to open before 9 months are over without pain or contractions. Some women may feel very mild discomfort or spotting for a few days, but this is only possible if you are between 14 to 20 weeks of pregnancy. However, look out for the following signs and symptoms, because they may indicate you’ve got an incompetent cervix 2:

- A feeling of pelvic pressure

- A new backache

- Mild cramps in your belly (abdomen)

- A change in vaginal discharge which changes from clear to pink

- Light vaginal bleeding or spotting

If your health care provider thinks you may have cervical insufficiency, she may check you regularly during pregnancy with transvaginal ultrasound starting at 16 to 20 weeks of pregnancy. Transvaginal ultrasound is an ultrasound in the vagina, not on the outside of your belly. An ultrasound is a prenatal test that uses sound waves and a computer screen to show a picture of your baby in the womb.

Cervical incompetence diagnosis

Often, you will not have any signs or symptoms of cervical insufficiency unless you have a problem it might cause. That is how many women first find out about it. Cervical incompetence is primarily a clinical diagnosis characterized by recurrent painless dilatation and spontaneous midtrimester birth, usually of a living fetus. The presence of risk factors for structural cervical weakness supports the diagnosis. The challenges in making the diagnosis are that relevant findings in prior pregnancy are often not well-documented and only a subjective assessment.

The diagnosis of cervical insufficiency is challenging because of the lack of objective findings and clear diagnostic criteria. Cervical ultrasound has emerged as a proven, clinically useful screening and diagnostic tool in the selected population of high-risk women based on an obstetrical history of a prior (early) spontaneous preterm birth. The transvaginal ultrasound typically shows a short cervical length, less than or equal to 25 mm, or funneling, ballooning of the membranes into a dilated internal os but with the closed external os.

The diagnosis of incompetent cervix is usually made in three different settings:

- Women who present with a sudden onset of symptoms and signs of cervical insufficiency

- Women who present with a history of second-trimester losses consistent with the diagnosis of cervical incompetence (history-based)

- Women with endovaginal ultrasound findings consistent with cervical incompetence (ultrasound diagnosis)

The digital or speculum examination reveals a cervix that is dilated 2 cm or more, effacement greater than or equal to 80%, and the bag of waters visible through the external orifice or protruding into the vagina. The diagnosis is frequently made on the basis of history retrospectively after multiple poor obstetrical outcomes have occurred 4.

If you have any of the risk factors for cervical incompetence:

- Your health care provider may do a transvaginal ultrasound to look at your cervix when you are planning a pregnancy, or early in your pregnancy.

- You may have physical exam and ultrasounds more often during your pregnancy.

A cervical insufficiency may cause these symptoms in the 2nd trimester:

- Abnormal vaginal spotting or bleeding

- Increasing pressure or cramps in the lower abdomen and pelvis

Cervical insufficiency treatment

Many nonsurgical and surgical modalities have been proposed to treat cervical insufficiency. Certain nonsurgical approaches, including activity restriction, bed rest, and pelvic rest have not proven effective in the treatment of cervical incompetence and their use is discouraged. Another nonsurgical treatment to be considered in patients at risk of cervical insufficiency is the vaginal pessary. The evidence is limited for a potential benefit of pessary placement in select high-risk patients 3.

Serial Ultrasounds

If you suffer from premature births, your doctor may recommend ultrasounds after every two weeks to monitor the cervix. This is done from the 15th week to the 26th week. If the cervix is seen to become weaker or open, your doctor may recommend cervical cerclage.

Medication

Some doctors may also recommend taking a medication like progesterone, a hormone that may help prevent premature birth. Progesterone supplementation can be recommended if you have had a history of premature births. Your doctor will recommend weekly shots of progesterone hormone on your 2nd trimester. However, further research is required to prove that progesterone can help women with the risk of cervix incompetence. Talk to your doctor if you have questions about progesterone.

Cerclage is also recommended as a form of treatment. This is especially if you suffered preterm labor when you were between sixteen and thirty four weeks of pregnancy. This procedure can be done on an outpatient basis. You’re required to relax after the treatment.

Steroids are also prescribed together with other drugs to prevent preterm labor. However, this can only be done after the 24 weeks mark where the child has a chance of survival. Steroids also help the baby’s lungs to develop quicker, which helps if the baby is to be born prematurely.

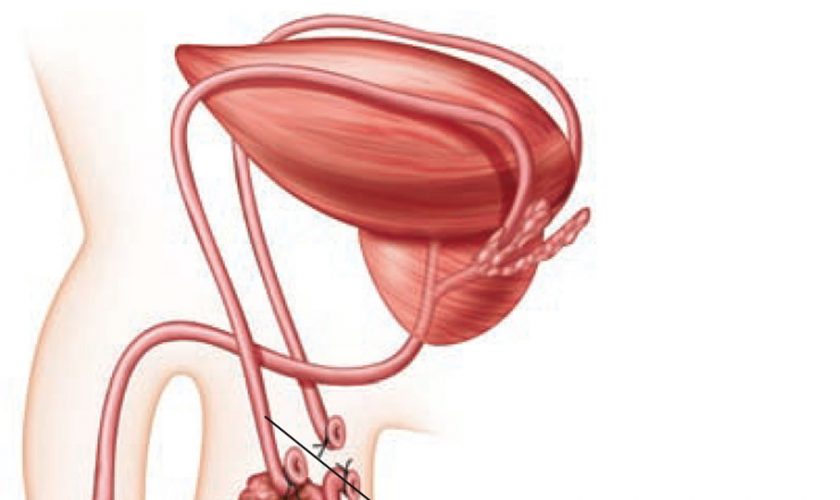

Cervical incompetence cerclage

Your doctor may recommend a cerclage 5. This is a stitch your doctor puts in your cervix to help keep it closed. If your pregnancy has not reached the 26th week mark and you have a history of early births, cerclage can prevent a premature birth. You can get a cerclage as early as 13 to 14 weeks of pregnancy, and your doctor removes the stitch at about 37 weeks of pregnancy. Cerclage may be right for you if you’re pregnant now with just one baby and:

- You had a cerclage in a past pregnancy.

- You’ve had one or more pregnancy losses in the second trimester.

- You had a spontaneous premature birth before 34 weeks in a past pregnancy with a cervix shorter than 25 millimeters (about 1 inch) before 24 weeks of pregnancy. Spontaneous means that labor began on its own.

- In this pregnancy, your cervix is opening in the second trimester.

However, this procedure is not ideal for every woman at risk of premature labor. It is important to talk to your doctor concerning the benefits and risks of cerclage.

A cerclage is NOT recommended if you’re pregnant with twins, even if your cervix is shorter than 25 millimeters.

A woman would not be eligible for a cerclage if:

- There is increased irritation of the cervix

- The cervix has dilated 4cm

- Membranes have ruptured

Possible complications of cervical cerclage include uterine rupture, maternal hemorrhage, bladder rupture, cervical laceration, preterm labor and premature rupture of the membranes. The likelihood of these risks is very minimal, and most health care providers feel that a cerclage is a life saving procedure that is worth the possible risks involved.

Transvaginal and transabdominal cervical cerclage

Surgical approaches include transvaginal and transabdominal cervical cerclage. The two types of this commonly used vaginal procedure include McDonald and modified Shirodkar. McDonald involves taking four or five bites of number 2 monofilament suture as high as possible in the cervix, trying to avoid injury to the bladder or the rectum, with a placement of a knot anteriorly to facilitate the removal. The Shirodkar procedure involves the dissection of the vesical-cervical mucosa in an attempt to place the suture as close to the cervical internal os as close, otherwise, as possible. The bladder and rectum are dissected from the cervix in a cephalad manner, the suture is placed and tied, and mucosa is replaced over the knot. Nonresorbable sutures should be used for cerclage placement using the Shirodkar procedure.

During an emergency, the cerclage patient is placed in Trendelenburg position and a bag of membranes is deflected cephalad back into the uterus by placing a Foley catheter with a 30 mL balloon through the cervix and inflating it. The balloon is deflated gradually as the cerclage suture is tightened 6.

Transabdominal cerclage with the suture placed at the uterine isthmus is used in some cases of severe anatomical defects of the cervix or cases of prior transvaginal cerclage failure. It can be performed laparoscopically, but it generally requires laparotomy for initial suture placement and subsequent laparotomy for removal of the suture, delivery of the fetus, or both 7.

Bed rest

Instead of the cerclage, some doctors will recommend bed rest. Also, bed rest can be recommended together with the different medical options. Even so, there is no substantial evidence to prove that bed rest works to prevent preterm labor, it works with the theory that relieving the cervix of the pressure can help.

- Thakur M, Davis DD, Mahajan K. Cervical Incompetence. [Updated 2020 May 27]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2020 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK525954[↩]

- Wei M, Jin X, Li TC, Yang C, Huang D, Zhang S. A comparison of pregnancy outcome of modified transvaginal cervicoisthmic cerclage performed prior to and during pregnancy. Arch. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018 Mar;297(3):645-652.[↩][↩]

- Wang HL, Yang Z, Shen Y, Wang QL. [Clinical outcome of therapeutic cervical cerclage in short cervix syndrome]. Zhonghua Fu Chan Ke Za Zhi. 2018 Jan 25;53(1):43-46.[↩][↩]

- Lee KN, Whang EJ, Chang KH, Song JE, Son GH, Lee KY. History-indicated cerclage: the association between previous preterm history and cerclage outcome. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018 Jan;61(1):23-29.[↩]

- Practice bulletin no. 142: cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol. 2014 Feb. 123(2 Pt 1):372-9.[↩]

- Negrete LM, Spalluto LB. Don’t be short-sighted: cervical incompetence in a pregnant patient with acute appendicitis. Clin Imaging. 2018 Sep – Oct;51:35-37.[↩]

- Mönckeberg M, Valdés R, Kusanovic JP, Schepeler M, Nien JK, Pertossi E, Silva P, Silva K, Venegas P, Guajardo U, Romero R, Illanes SE. Patients with acute cervical insufficiency without intra-amniotic infection/inflammation treated with cerclage have a good prognosis. J Perinat Med. 2019 Jul 26;47(5):500-509.[↩]