Vitamins and supplements for hair growth

Hair loss also known as alopecia is a common problem that affects up to 50 percent of men and women throughout their lives 1. Hair loss can also affect children. Hair loss can affect people of all ages. Hair loss can occur anywhere on your body, but more commonly affecting just your scalp where it can cause concerns about the cosmetic effect. Studies have shown that hair loss can be associated with low self-esteem, anxiety, depression, introversion, and feelings of unattractiveness 2, 3.

This is reinforced by attitudes in Western society, which place great value on youthful appearance and attractiveness. Some studies have shown that based on appearance alone, men with hair loss are seen as less attractive, less assertive, less likeable, and less successful than men without hair loss.

Hair loss can occur in different patterns, depending on the cause. The hair loss can be temporary or permanent.

Hair loss is not usually anything to be worried about, but occasionally it can be a sign of a medical condition.

Some types of hair loss are permanent, like male and female pattern baldness also known as androgenic alopecia or androgenetic alopecia. This type of hair loss usually runs in the family.

Hair loss occurs in:

- Men and women

- Children and adults

- People with any color or type of hair.

Hair loss can be an isolated problem or associated with another disease or condition, including:

- A family history of balding on your mother’s or father’s side. Androgenic alopecia also known as androgenetic alopecia is the modern medical term for either male pattern hair loss or female pattern baldness caused by a combination of genetic and hormonal factors 4. Androgenic alopecia represents close to 95% of all hair loss. This hair loss causes a receding hairline and lack of hair on the top of the head. This type of hair loss can be defined in two parts. First, andro- means to consist of androgens which are various hormones that control the appearance and development of masculine characteristics such as testosterone. Second is genetics, or the inheritance of genes from either the mother or father. Age added to genetics creates a time clock that signals the hair follicle to produce an enzyme named 5-alpha reductase. When testosterone is present in the hair follicle and it combines with the enzyme 5-alpha reductase, it produces dihydrotestosterone (DHT). DHT (dihydrotestosterone) attacks the hair follicle, causing it to shrink, finally causing the hair to fall out and not grow back. Hair follicle receptors are sensitive to DHT and thereby start the process of male or female pattern hair loss 5.

- Age

- Significant weight loss

- Prolonged fever

- Certain medical conditions, such as diabetes and lupus

- Stressful conditions, physical or emotional, such as illness or surgery

- Poor nutrition

- Drug treatment for cancer

- Autoimmune disease

- A localized infection, such as tinea capitis

- Severe local skin disease, such as psoriasis, seborrheic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- Generalized skin disease (erythroderma)

- Traumatic causes

- Other causes of hair loss include certain medicines (e.g., chemotherapy drugs, contraceptives, anticoagulants, anticonvulsants), low levels of iron in your blood (iron deficiency), pregnancy (after childbirth), syphilis, thyroid disease, systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and repeated hair twisting

- Unknown causes.

Hair loss can be temporary or permanent, depending on the cause.

- Hair loss may be localized or diffuse.

- Hair loss can affect the scalp or other parts of the body.

- Hair loss may be due to hair shedding, poor quality hair, or hair thinning.

- There may be areas of skin that are completely bald.

- There may be associated skin disease or scarring.

Local hair loss in one or more small parts of the scalp can be caused by any of the following:

- Alopecia areata (patchy hair loss; the cause is unknown)

- Traction alopecia (tight hairstyles such as cornrows or pigtails)

- Trichotillomania (repeated hair pulling or nervous hair twisting or twirling)

- Tinea capitis (ringworm or fungal infection)

Since hair loss may be an early sign of a disease, it is important to find the cause so that it can be treated.

If you suspect that you may have excessive hair loss, talk to your doctor. He or she will probably ask you some questions about your diet, any medicines you’re taking, and whether you’ve had a recent illness, and how you take care of your hair. If you’re a woman, your doctor may ask questions about your menstrual cycle, pregnancies, and menopause. Your doctor may want to do a physical exam to look for other causes of hair loss. Finally, your doctor may order blood tests to measure hormone levels, serum ferritin and thyroid function or a biopsy (taking a small sample of cells to examine under a microscope). Your doctor will usually diagnose androgenetic alopecia by examining the pattern of hair loss on the scalp.

Treatment for hair loss depends on the cause. In some cases, treating the underlying cause will correct the problem. With some conditions, such as patchy hair loss (alopecia areata), hair may regrow without treatment within a year.

If a medicine is causing your hair loss, your doctor may be able to prescribe a different medicine. Recognizing and treating an infection may help stop the hair loss. Correcting a hormone imbalance may prevent further hair loss.

Sometimes changing how you style or treat your hair can help. Getting rid of stress in your life can also help. Other treatments include changing your diet, correcting any hormone imbalances, switching medicines, treating infections, or getting shots into your scalp.

Medicines may also help slow or prevent the development of common baldness. One medicine that is used to slow hair loss, minoxidil (brand name: Rogaine), is available without a prescription. It is applied to the scalp. Both men and women can use it. Minoxidil (Rogaine) is the only US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved topical treatment for male or female pattern hair loss. Although minoxidil (Rogaine) is not effective in stimulating new hair growth in many males, it appears to be more effective in retarding hair loss in a substantial amount of both male and females.

Another medicine, finasteride (type II 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor), is available with a prescription. It comes in pills and is only for men. 5 alpha reductase converts testosterone into dihydrotestosterone (DHT). DHT (dihydrotestosterone) binding to the scalp hair follicle androgen receptors produces male pattern hair loss. For men, finasteride tablets reduce levels of dihydrotestosterone (DHT), which may slow hair loss and possibly help regrowth of hair 6. A daily oral finasteride dose of one milligram reduces scalp dihydrotestosterone by 64% and serum dihydrotestosterone by 68% 7. Continuous use for 3 to 6 months is required before a benefit is usually seen. It may take up to 6 months before you can tell if one of these medicines is working. When you stop taking these medicines, any beneficial effects on hair growth will be lost within 6 to 12 months of discontinuing treatment. Decreased libido and erectile problems are recognized side-effects of this treatment.

If treatment doesn’t work or is not available for your type of hair loss, you may want to consider wearing a wig, hairpiece, hair weave, or artificial hair replacement.

Despite the widespread use of supplements and vitamins for hair growth or hair loss, the safety and effectiveness of available products remain unclear 8. Studies of nutritional interventions with the highest-quality evidence showed the potential benefit of Viviscal, Nourkrin, Nutrafol, Lambdapil, Pantogar, capsaicin and isoflavone, omegas 3 and 6 with antioxidants, apple nutraceutical, total glucosides of paeony and compound glycyrrhizin tablets, zinc, tocotrienol, and pumpkin seed oil 8. Kimchi and cheonggukjang, vitamin D3, and Forti5 had low-quality evidence for hair growth 8.

Figure 1. Male pattern hair loss

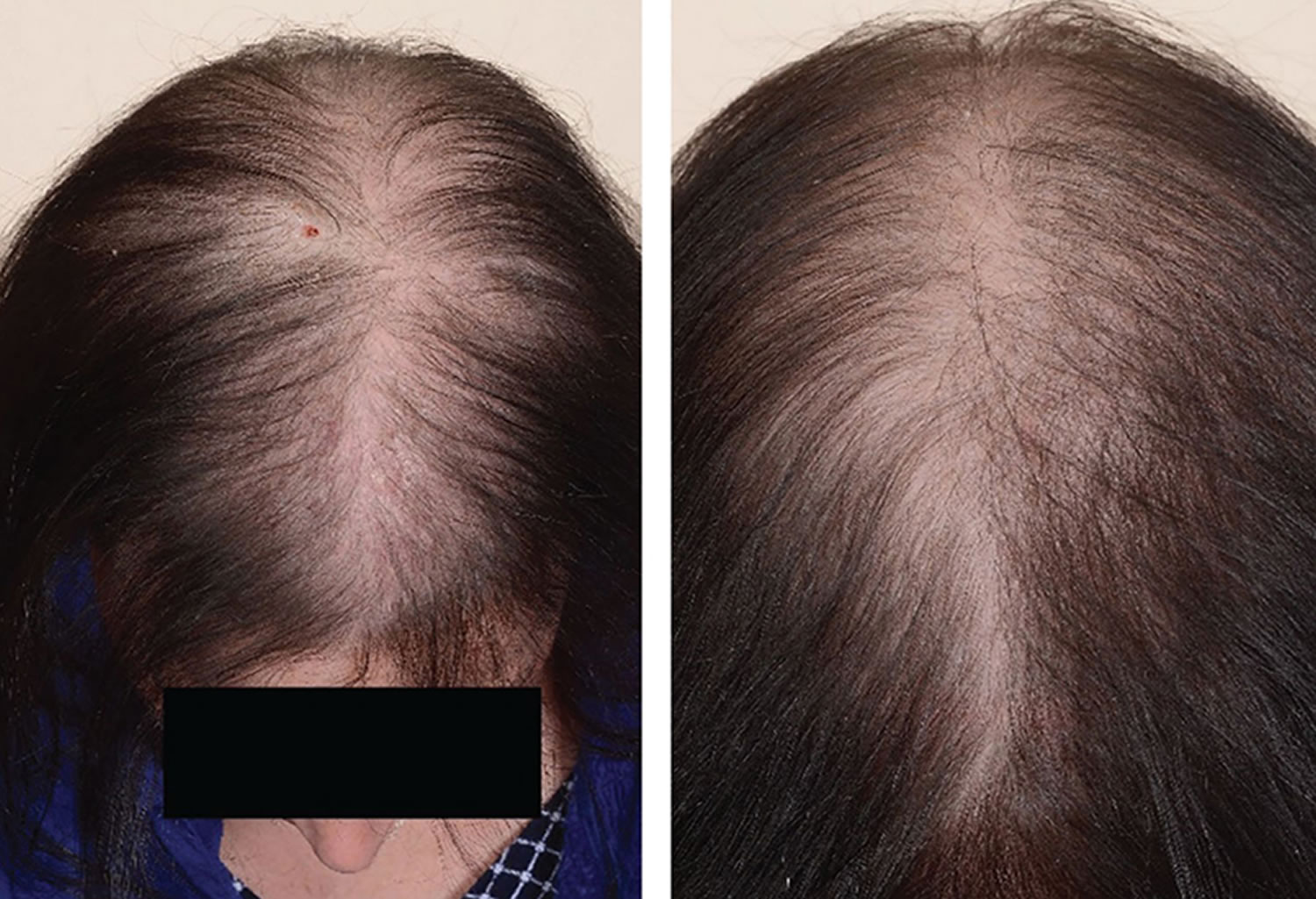

Figure 2. Female pattern hair loss

See your doctor if you are distressed by persistent hair loss in you or your child and want to pursue treatment. For women who are experiencing a receding hairline (frontal fibrosing alopecia), talk with your doctor about early treatment to avoid significant permanent baldness.

Also talk to your doctor if you notice sudden or patchy hair loss or more than usual hair loss when combing or washing your or your child’s hair. Sudden hair loss can signal an underlying medical condition that requires treatment.

Also if you are having significant, persistent hair loss or if there is redness, itching, or skin changes associated with the hair loss, seek medical advice, as there are sometimes other causes for hair loss that can be treated.

Lastly, if you have hair loss that is cosmetically concerning and other causes have been ruled out, you might consult a surgical specialist in hair replacement.

What is male pattern hair loss?

Male pattern hair loss also known as androgenic alopecia or androgenetic alopecia, is the most common type of diffuse thinning of the hair and balding that occurs in adult males.

- Male pattern hair loss is due to a combination of hormones (androgens) and a genetic predisposition.

- Male pattern hair loss is characterized by a receding hairline and hair loss on the top and front of the head.

- A similar type of hair loss in women, female pattern hair loss, results in thinning hair on the mid-frontal area of the scalp and is generally less severe than occurs in males.

What causes male pattern baldness?

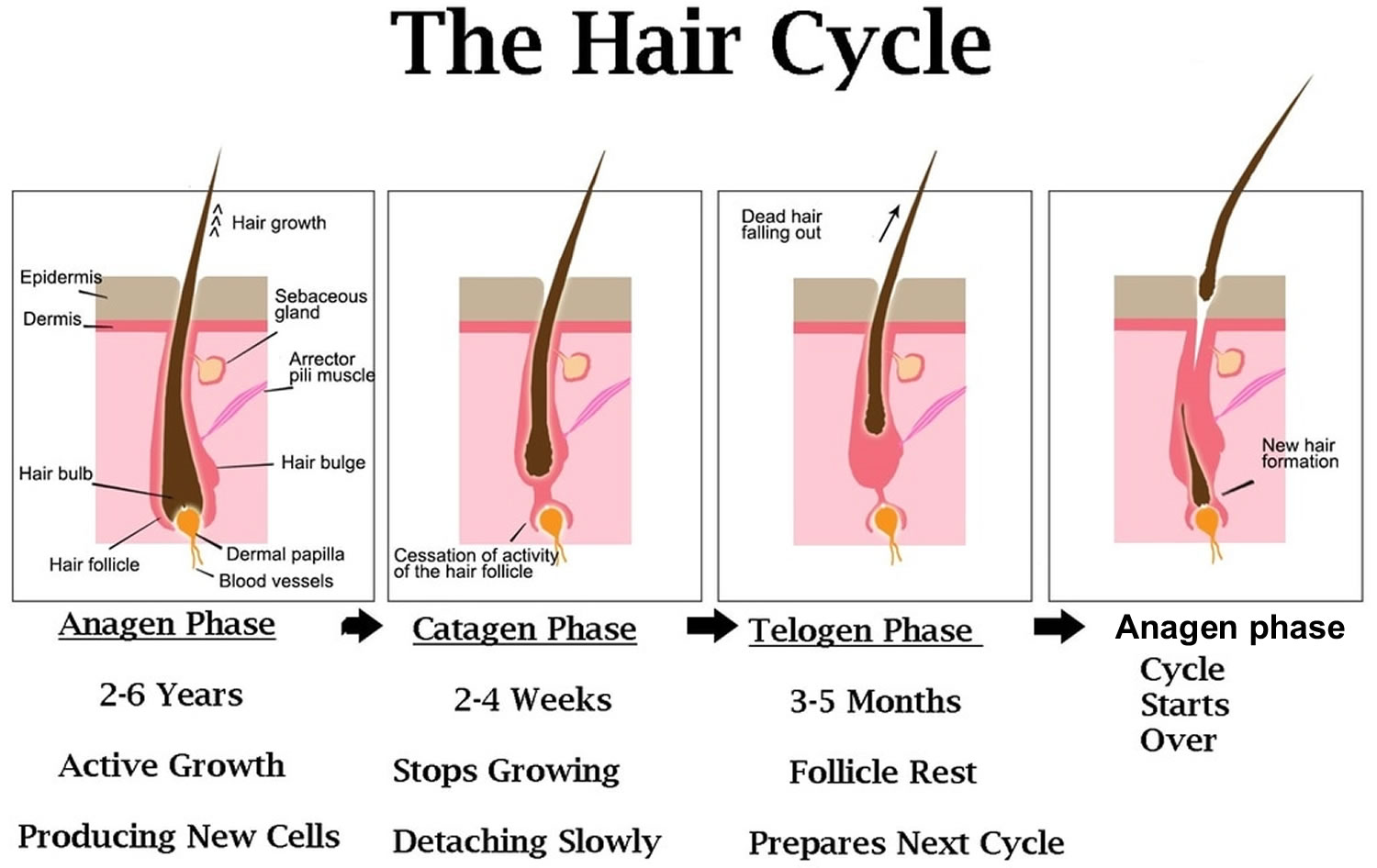

Male pattern hair loss is an inherited condition, caused by a genetically determined sensitivity to the effects of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in some areas of the scalp. DHT (dihydrotestosterone) is believed to shorten the growth, or anagen phase of the hair cycle, from a usual duration of 3–6 years to just weeks or months. This occurs together with miniaturisation of the follicles and progressively produces fewer and finer hairs. The production of DHT is regulated by an enzyme called 5-alpha reductase.

Male pattern hair loss occurs in men who are genetically predisposed to be more sensitive to the effects of DHT. Researchers now believe that the condition can be inherited from either side of the family.

Several genes are involved, accounting for differing age of onset, progression, pattern and severity of hair loss in family members. The susceptibility genes are inherited from both mother and father. At this time, genetic testing for prediction of balding is unreliable.

A few women present with male pattern hair loss because they have excessive levels of androgens as well as genetic predisposition. These women also tend to suffer from acne, irregular menses and excessive facial and body hair. These symptoms are characteristic of polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) although the majority of women with PCOS do not experience hair loss. Less often, congenital adrenal hyperplasia may be responsible. Females that are losing their hair with age are more likely to present with female pattern hair loss, in which hormone tests are normal.

Is male pattern hair loss hereditary?

Yes. It is believed male pattern hair loss can be inherited from either or both parents.

How common is male pattern hair loss?

Male pattern hair loss affects nearly all men at some point in their lives. It affects different populations at different rates, probably because of genetics. Up to half of male Caucasians will experience some degree of hair loss by age 50, and possibly as many as 80% by the age of 70 years, while other population groups such as Japanese and Chinese men are far less affected.

Can male pattern hair loss be cured?

No, there is no cure. However, it tends to progress very slowly, from several years to decades. An earlier age of onset may lead to quicker progression.

Can my hairstyle cause hair loss?

Wigs, tight braids, hair weaves, and the use of hair curlers can damage hair and lead to hair loss. Hair processing (such as bleaching, coloring, and perming) can also damage hair and cause hair loss. Your hair will usually grow back once you stop stressing your hair. In certain cases, it can lead to scarring and permanent hair loss.

What treatments are available for male pattern hair loss?

Current male pattern hair loss treatment options include:

- Hair replacement / transplantation

- Cosmetics

- Micropigmentation (tattoo) to resemble shaven scalp

- Hairpieces

- Minoxidil solution

- Finasteride tablets (type II 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor)

- Dutasteride (type I and type II 5-alpha-reductase inhibitor).

A phase 2 randomized placebo-controlled study of dutasteride versus finasteride showed that the effect of dutasteride was dose dependent and 2.5mg of dutasteride was superior to 5mg finasteride in improving scalp hair growth in men between the ages of 21 and 45 years 9. It was also able to produce hair growth earlier than finasteride. This was evidenced by target area hair counts and clinical assessment at 12 and 24 weeks. In addition, a recent randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled study on the efficacy of dutasteride 0.5mg/day in identical twins demonstrated that dutasteride was able to significantly reduce hair loss progression in men with male pattern hair loss 10. A single case report showed improvement of hair loss with dutasteride 0.5mg in a woman who had failed to show any response to finasteride 11, 12.

In one phase 3 study dutasteride 0.5 mg daily showed significantly higher efficacy than placebo based on subject self-assessment and by investigator and panel photographic assessment 13. There was no major difference in adverse events between two groups the treatment and placebo groups. However, this study was limited to only 6 months. Another more recent phase 3 trial found that dutasteride 0.5 mg was statistically superior to finasteride 1 mg and placebo at 24 weeks 14.

There is some evidence that ketoconazole shampoo may also be of benefit, perhaps because it is effective in seborrheic dermatitis and dandruff 15, 16. Low-dose oral minoxidil (off label) can increase hair growth on the scalp, but may also result in generalized hypertrichosis and other adverse effects 17.

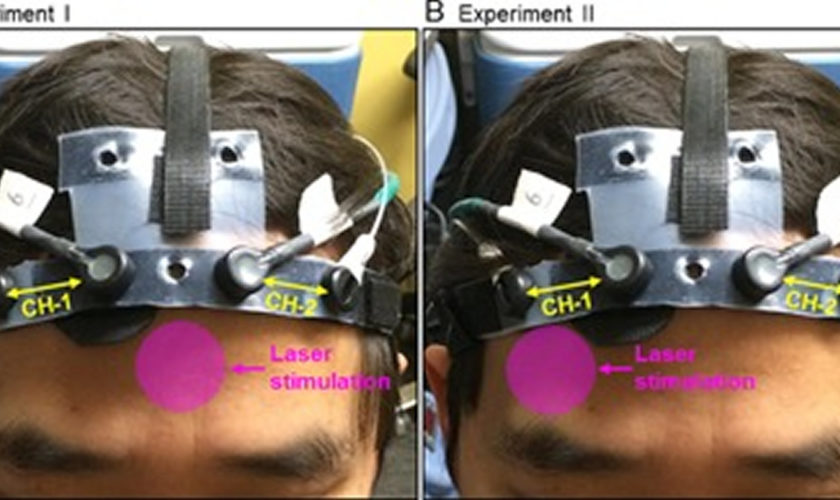

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is of unproven benefit in male pattern balding; the Capillus® laser cap and Hairmax® Lasercomb/Laserband are two low‐level laser therapy (LLLT) devices have been approved by the FDA for the management of androgenetic alopecia 18, 19. Minimal side effects were reported. Small number of participants reported adverse events of acne, mild paresthesia such as burning sensation, dry skin, headache, and itch 20.

Light‐emitting diode (LED) devices. In contrast with low-level laser therapy (LLLT) that delivers a single, collimated wavelength of light, light‐emitting diode (LED) devices may emit a small band of wavelengths. In particular, an all‐LED device that delivers dual dark orange (620 nm) and red light (660 nm) (Revian Red) to promote blood flow, reduce inflammation, and inhibit DHT via 5-alpha-reductase downregulation 21. In a prospective, randomized, double‐blind, controlled study, 18 male pattern hair loss subjects were treated with Revian Red cap vs. 18 male pattern hair loss subjects were treated with a sham light device for 10 min daily for 16 weeks total 22. Preliminary photographic assessments revealed increased mean hair count in the active group as compared to placebo group. Specifically, active group participants demonstrated approximately 26.3 more hairs per cm² compared to the placebo group. Overall, literature has suggested light therapy to be a safe treatment modality for androgenic alopecia (androgenetic alopecia) in both male and female patients when used independently or in combination with topical/oral therapies 20, 23. Light therapy has an excellent side effect profile, and there are no contraindications for use, although caution may be taken when administering in patients with dysplastic lesions on the scalp 24.

Platelet-rich plasma injections are also under investigation 25. Platelet‐rich plasma treatment can be administered alone or in combination with other therapies for androgenetic alopecia, although better results are obtained if platelet‐rich plasma administration is used in association with topical (such as minoxidil) or oral therapies (finasteride) 25. Further studies are required to determine the magnitude of the benefit if any.

Platelet‐rich plasma is generally indicated for patients with early‐stage androgenic alopecia, as intact hair follicles are present and a more significant hair restorative effect can be achieved 26. During the procedure, approximately 10–30 mL of blood are drawn from the patient’s vein and centrifuged for 10 min in order to separate the plasma from red blood cells. The platelet‐rich plasma, containing numerous growth factors, is then injected into the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue at a volume of 4–8 mL per session. Mild side effects include scalp pain, headache, and burning sensation, but these effects usually subside in 10–15 minutes post‐injection and do not warrant use of topical anesthesia or pain medications 27. Vibration or cool air is typically sufficient to alleviate any significant pain that a patient may feel from the treatment. Patients can resume regular activities immediately after treatment but should avoid strenuous physical activity 24 hour post‐treatment to allow for optimal absorption of platelet‐rich plasma into tissue.

Hausauer and Jones 28 conducted a single center, blinded, randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy of two platelet‐rich plasma regimens in 40 androgenic alopecia subjects. Participants received either subdermal platelet‐rich plasma injections with 3 monthly sessions and booster 3 months later (group 1) or 2 sessions every 3 months (group 2). Folliscope hair count and shaft caliber, global photography, and patient satisfaction questionnaires were completed at baseline, 3‐month, and 6‐month visits. The authors reported statistically significant increases in hair count and shaft caliber in both groups at 6 months. Importantly, improvements occurred more rapidly and profoundly in group 1, indicating that platelet‐rich plasma injections should be administered first monthly 28. Alves and Grimalt 29 demonstrated significant differences in mean anagen hair and telogen hair count as well as telogen and overall hair density when compared to baseline. In a review of 16 studies comprising a total of 389 patients with androgenic alopecia, the majority demonstrated efficacy in promoting successful hair growth after 3–4 sessions on a monthly basis, followed by quarterly maintenance sessions 30.

Platelet‐rich plasma is not curative for hair loss and must be continued long term for hair sustenance. However, patient satisfaction is typically very high and 60–70% of patients continue to undergo maintenance treatments. Due to the relatively recent introduction of platelet‐rich plasma injections for androgenic alopecia, there are no long‐term studies evaluating its effectiveness. Additionally, it is difficult to compare the efficacy with other remedies due to the lack of standardization in regard to platelet‐rich plasma kits, treatment fractions, and regimens, including the use of newer multi‐needle injectors.

While platelet‐rich plasma injections are considered safe when performed by a trained medical provider, these treatments are not suitable for everyone. Platelet‐rich plasma may not be appropriate for those with a history of bleeding disorders, autoimmune disease, or active infection, or those currently taking an anticoagulant medication. Although the majority of patients seem to tolerate the pain associated with scalp injections, some patients may prefer to avoid it.

Clascoterone gained FDA approval in August 2020 as the first topical antiandrogen agent to treat hormonal acne. The clascoterone molecule resembles DHT and spironolactone in molecular structure and works by antagonizing androgen receptors on dermal papillae and inhibiting DHT’s effect on hair miniaturization and dermal inflammation 31. Due to its mechanism of action, clascoterone has potential in treating androgenic alopecia. In a 6‐month dose‐ranging study, patients with androgenic alopecia who received clascoterone 7.5% twice a day showed a significant improvement in hair loss from baseline and compared to those who received placebo 32.

What is female pattern hair loss?

Female pattern hair loss also known as androgenic alopecia or androgenetic alopecia, is a distinctive form of diffuse hair loss that occurs in women. Many women are affected by female pattern hair loss. Around 40% of women by age 50 show signs of hair loss and less than 45% of women reach the age of 80 with a full head of hair.

In female pattern hair loss, there is diffuse thinning of hair on the scalp due to increased hair shedding or a reduction in hair volume, or both. It is normal to lose up to 50-100 hairs a day. Another condition called chronic telogen effluvium also presents with increased hair shedding and is often confused with female pattern hair loss. It is important to differentiate between these conditions as management for both conditions differ.

Female pattern hair loss presents quite differently from the more easily recognizable male pattern baldness, which usually begins with a receding frontal hairline that progresses to a bald patch on top of the head. It is very uncommon for women to bald following the male pattern unless there is excessive production of androgens in the body.

What causes female pattern hair loss?

Female pattern hair loss has a strong genetic predisposition. The mode of inheritance is polygenic, indicating that there are many genes that contribute to female pattern hair loss, and these genes could be inherited from either parent or both. Genetic testing to assess the risk of balding is currently not recommended, as it is unreliable.

Currently, it is not clear if androgens (male sex hormones) play a role in female pattern hair loss, although androgens have a clear role in male pattern baldness. The majority of women with female pattern hair loss have normal levels of androgens in their bloodstream. Due to this uncertain relationship, the term female pattern hair loss is preferred to ‘female androgenetic alopecia’.

The role of estrogen is uncertain. female pattern hair loss is more common after the menopause suggesting estrogens may be stimulatory for hair growth. But laboratory experiments have also suggested estrogens may suppress hair growth.

What treatments are available for female pattern hair loss?

A Cochrane systematic review published in 2012 33 concluded that minoxidil solution was effective for female pattern hair loss. Minoxidil is available as 2% and 5% solutions; the stronger preparation is more likely to irritate and may cause undesirable hair growth unintentionally on areas other than the scalp.

Hormonal treatment, i.e. anti-androgen medicines are oral medications that block the effects of androgens (e.g. spironolactone, cyproterone acetate, finasteride and flutamide) is also often tried. These medicines help stop hair loss and may also stimulate hair regrowth. Spironolactone has been shown to stop the loss of hair in 90 per cent women with androgenetic alopecia. In addition, partial hair regrowth occurs in almost half of treated women. The effects of treatment generally only last while you continue to take the medicine – stopping the medicine will mean that your hair loss will return. Spironolactone and cyproterone acetate should not be taken during pregnancy. Effective contraception must be used while you are being treated with these medicines, as it can affect a developing baby. These medicines should also not be taken if you are breast feeding.

A combination of low dose oral minoxidil (eg, 2.5 mg daily) and spironolactone (25 mg daily) has been shown to significantly improve hair growth, reduce shedding and improve hair density.

Once started, treatment needs to continue for at least six months before the benefits can be assessed, and it is important not to stop treatment without discussing it with your doctor first. Long term treatment is usually necessary to sustain the benefits.

It takes about 4 months of using minoxidil to see any obvious effect. You might have some hair loss for the first couple of weeks as hair follicles in the resting phase are stimulated to move to the growth phase. You need to keep using minoxidil to maintain its effect – once you stop treatment the scalp will return to its previous state of hair loss within 3 to 4 months. Also, be aware that minoxidil is not effective for all women, and the amount of hair regrowth will vary among women. Some women experience hair regrowth while in others hair loss is just slowed down. If there is no noticeable effect after 6 months, it’s recommended that treatment is stopped.

Always carefully follow the directions for use, making sure you use minoxidil only when your scalp and hair are completely dry. Take care when applying minoxidil near the forehead and temples to avoid unwanted excessive hair growth. Wash your hands after use.

The most common side effects of minoxidil include a dry, red and itchy scalp. Higher-strength solutions are more likely to cause scalp irritation.

Bear in mind that minoxidil is also used in tablet form as a prescription medicine to treat high blood pressure, and there is a small chance that minoxidil solution could possibly affect your blood pressure and heart function. For this reason, minoxidil is generally only recommended for people who do not have heart or blood pressure problems.

Minoxidil should not be used if you are pregnant or breast feeding.

Side effects of spironolactone can include:

- irregular periods and spotting;

- breast tenderness or lumpiness; and

- tiredness.

Side effects of cyproterone acetate can include:

- spotting and irregular periods;

- tiredness;

- weight gain;

- reduced libido; and

- depressed mood.

Cosmetic camouflages include colored hair sprays to cover thinning areas on the scalp, hair bulking fiber powder, and hair wigs. Hair transplantation for female pattern hair loss is becoming more popular although not everyone is suitable for this procedure. Your doctor can refer you to a hair transplant surgeon to assess whether hair transplant surgery may be a suitable option for you.

Hair transplant surgery involves follicular unit transplantation, where tiny clusters of hair-producing tissue (each containing up to 4 hairs) are taken from areas of the scalp where hair is growing well and surgically attached (grafted) onto thinning areas. However, if your hair is very thin all over your scalp, you may not have enough healthy hair to transplant.

Hair transplant surgery can be expensive and painful, and multiple procedures are sometimes needed. Side effects may include infection and scarring.

Low-level laser therapy (LLLT) is of unproven benefit in female pattern balding; the Capillus® laser cap and Hairmax® Lasercomb/Laserband are two low‐level laser therapy (LLLT) devices have been approved by the FDA for the management of androgenetic alopecia 34, 18, 19. In a randomized, double‐blind, placebo‐controlled trial comprising 42 female subjects with androgenetic alopecia, 24 active group subjects were treated with 655 nm low-level laser therapy (LLLT) vs. 18 placebo group subjects were treated with incandescent red lights (sham) 34. Subjects were treated on alternate days for 16 weeks, and photography and hair count assessments revealed a 37% increase in terminal hair counts in the active treatment group as compared to the control group. In a review of 11 trials, 10 demonstrated significant improvement in androgenetic alopecia compared to baseline or controls when treated with low-level laser therapy (LLLT) 20. Two of the trials demonstrated efficacy for low-level laser therapy (LLLT) in combination with topical minoxidil, and one trial showed efficacy in combination with finasteride 26. Small number of participants reported adverse events of acne, mild paresthesia such as burning sensation, dry skin, headache, and itch 20.

Overall, literature has suggested light therapy to be a safe treatment modality for androgenic alopecia (androgenetic alopecia) in both male and female patients when used independently or in combination with topical/oral therapies 20, 23. Light therapy has an excellent side effect profile, and there are no contraindications for use, although caution may be taken when administering in patients with dysplastic lesions on the scalp 24.

Platelet‐rich plasma (PRP) injections are also under investigation 25. Further studies are required to determine the magnitude of the benefit if any.

Platelet‐rich plasma is generally indicated for patients with early‐stage androgenic alopecia, as intact hair follicles are present and a more significant hair restorative effect can be achieved 26. During the procedure, approximately 10–30 mL of blood are drawn from the patient’s vein and centrifuged for 10 min in order to separate the plasma from red blood cells. The platelet‐rich plasma, containing numerous growth factors, is then injected into the deep dermis or subcutaneous tissue at a volume of 4–8 mL per session. Mild side effects include scalp pain, headache, and burning sensation, but these effects usually subside in 10–15 minutes post‐injection and do not warrant use of topical anesthesia or pain medications 27. Vibration or cool air is typically sufficient to alleviate any significant pain that a patient may feel from the treatment. Patients can resume regular activities immediately after treatment but should avoid strenuous physical activity 24 hour post‐treatment to allow for optimal absorption of platelet‐rich plasma into tissue.

Hausauer and Jones 28 conducted a single center, blinded, randomized controlled trial investigating the efficacy of two platelet‐rich plasma regimens in 40 androgenic alopecia subjects. Participants received either subdermal platelet‐rich plasma injections with 3 monthly sessions and booster 3 months later (group 1) or 2 sessions every 3 months (group 2). Folliscope hair count and shaft caliber, global photography, and patient satisfaction questionnaires were completed at baseline, 3‐month, and 6‐month visits. The authors reported statistically significant increases in hair count and shaft caliber in both groups at 6 months. Importantly, improvements occurred more rapidly and profoundly in group 1, indicating that platelet‐rich plasma injections should be administered first monthly 28. Alves and Grimalt 29 demonstrated significant differences in mean anagen hair and telogen hair count as well as telogen and overall hair density when compared to baseline. In a review of 16 studies comprising a total of 389 patients with androgenic alopecia, the majority demonstrated efficacy in promoting successful hair growth after 3–4 sessions on a monthly basis, followed by quarterly maintenance sessions 30. Platelet‐rich plasma is not curative for hair loss and must be continued long term for hair sustenance. However, patient satisfaction is typically very high and 60–70% of patients continue to undergo maintenance treatments. Due to the relatively recent introduction of platelet‐rich plasma injections for androgenic alopecia, there are no long‐term studies evaluating its effectiveness. Additionally, it is difficult to compare the efficacy with other remedies due to the lack of standardization in regard to platelet‐rich plasma kits, treatment fractions, and regimens, including the use of newer multi‐needle injectors.

While platelet‐rich plasma injections are considered safe when performed by a trained medical provider, these treatments are not suitable for everyone. Platelet‐rich plasma may not be appropriate for those with a history of bleeding disorders, autoimmune disease, or active infection, or those currently taking an anticoagulant medication. Although the majority of patients seem to tolerate the pain associated with scalp injections, some patients may prefer to avoid it.

How does hair grow?

Hair grows on most parts of the skin surface, except palms, soles, lips and eyelids. Hair thickness and length varies according to the site.

- Vellus hair is fine, light in colour, and short in length

- Terminal or androgenic hair is thicker, darker and longer

A hair shaft grows within a hair follicle at a rate of about 1 cm per month. It is due to cell division within the hair bulb at the base of the follicle. The cells produce the three layers of the hair shaft (medulla, cortex, cuticle), which are mainly made of the protein keratin (which is also the main structure of skin and nails).

The human scalp contains about 100,000 hair follicles. These anchor the hair to the skin and contain the cells that produce new hairs (Figure 3).

Hair grows in 3 phases. However, these phases are not synchronized, and any hair may be at a particular phase at random.

The 3 main phases of the hair growth cycle are:

- The anagen or follicle growing phase starts growing the new hair (about 90% of hairs). This phase is genetically determined and can vary from 2 to 6 years (the average is just under 3 years). Most hair follicles on the scalp are in the anagen phase.

- The catagen phase (less than 10% of hairs) is a transition stage between the growing and resting phases and lasts 1-2 weeks.

- The telogen or resting phase (5% to 10% of hairs) is a mature hair with a root, which is held very loosely in the follicle. The telogen phase generally lasts about 4-5 months. About 100 telogen hairs are lost from the human scalp each day.

Because each hair follicle passes independently through the three stages of growth, the normal process of hair loss usually is unnoticeable. At any one time, approximately 85 to 90 percent of scalp hair follicles are in the anagen phase of hair growth. Hair follicles remain in anagen phase for an average of three years (range, two to six years) 35. The transitional or catagen phase of follicular regression follows, usually affecting 2 to 3 percent of hair follicles. Finally, the telogen phase occurs, during which 10 to 15 percent of hair follicles undergo a rest period for about three months. At the conclusion of this phase, the inactive or dead hair is ejected from the skin, leaving a solid, hard, white nodule at its proximal hair shaft 36. The hair growth cycle is then repeated.

Different causes of hair loss affect the hair follicles in different phases of growth. See below for the different types of hair loss (What are causes of hair loss?).

What is normal hair growth and hair loss?

Hair normally grows in cycles of two to six years. Each hair grows about one centimeter per month during a cycle. About 90 percent of your hair is growing, and about 10 percent is resting. After two to three months, the resting hair falls out and new hair starts to grow in its place. It is normal to lose up to 100 hairs each day. But, some people may have more hair loss than normal. This can be stressful, can lead to depression, and may affect self-confidence.

The scalp contains, on average, 100,000 hair follicles 37. You lose up to 100 hairs from your scalp every day. That’s normal, and in most people, those hairs grow back. A hair shaft grows within a hair follicle at a rate of about 1 – 1.5 cm per month. It is due to cell division within the hair bulb at the base of the hair follicle. The cells produce the three layers of the hair shaft (medulla, cortex, cuticle), which are mainly made of the protein keratin (which is also the main structure of skin and nails). Hair growth follows a cycle and the hair growth cycle is divided into three phases: anagen (active growing stage, about 90 % of hairs), catagen (degeneration stage, less than 10% of hairs) and telogen (resting stage, 5% to 10% of hairs). Hair is shed during the telogen phase. When telogen hairs are shed, new anagen hairs grow to replace them, beginning a new cycle 38, 39. These phases are not synchronized, and any hair may be at a particular phase at random. Hair length depends on the duration of anagen. Short hairs (eyelashes, eyebrows, hair on arms and legs) have a short anagen phase of around one month. Anagen lasts up to 6 years or longer in scalp hair. In addition to the ratio of anagen hair to telogen hair, the diameter of the hair follicles determines scalp coverage. Vellus hairs have a hair-shaft diameter of less than 0.03 mm, whereas terminal hairs have a diameter greater than 0.06 mm. The optimal hairs for scalp-hair growth and scalp coverage are anagen and terminal hairs.

Timespan of the hair growth cycle

- The anagen phase constitutes about 90% (1000 days or more) of the growth cycle. Anagen hairs are anchored deeply into the subcutaneous fat and cannot be pulled out easily.

- The catagen phase (10 days) and telogen phase (100 days) constitute only 10% of the hair growth cycle.

- During the catagen and telogen phase of the hair growth cycle, as hairs are at the shedding and rest-from-growth period, no bald spots are shown as hairs are randomly distributed over the scalp.

Anagen (active growing stage, about 90 % of hairs) stage

Your hair grows around 1 – 1.5 cm per month, faster in summer than in winter.

- The anagen stage is the growing period of a hair follicle.

- This stage typically lasts about 3 to 5 years. Asian hair can last 5-7 years

- Full length hair can be upto 100 cm long

Catagen (degeneration stage, less than 10% of hairs) stage

At the end of the anagen phase, your hair enters the catagen phase.

The catagen stage is the intermediate period of hair growth.

- Hair follicles prepare themselves for the resting phase.

- It lasts around 1-2 weeks.

- During this phase, the deeper portions of the hair follicles start to collapse.

Telogen (resting stage, 5% to 10% of hairs) stage

During the telogen phase each hair is released and falls out

- The telogen stage is the resting and shedding period of the hair cycle.

- The follicle remains inactive for 3 to 4 months.

- At the end of this period, older hairs that have finished their life will fall out and newer hairs will begin to grow.

- As compared with anagen hair, telogen hair is located higher in the skin and can be pulled out relatively easily. Normally, the scalp loses approximately 100 telogen hairs per day.

Hair loss, hair thinning and problems with hairgrowth occur when the growth cycle is interrupted/disrupted. This can be triggered by conditions such as nutritional and medical situations, illness or stress. For instance 6 weeks after intensive dieting or stress you can experience hair loss. This occurs because the growing stage (Anagen) is cut short and hairs enter the falling (Telogen) stage at the same time.

Figure 3. Hair growth cycle

What are causes of hair loss?

People typically lose 50 to 100 hairs a day. This usually isn’t noticeable because new hair is growing in at the same time. Hair loss occurs when new hair doesn’t replace the hair that has fallen out.

Hair loss is typically related to one or more of the following factors:

- Family history (heredity). The most common cause of hair loss is a hereditary condition that happens with aging. This condition is called androgenic alopecia (androgenetic alopecia), male-pattern baldness and female-pattern baldness. It usually occurs gradually and in predictable patterns — a receding hairline and bald spots in men and thinning hair along the crown of the scalp in women.

- Hormonal changes and medical conditions. A variety of conditions can cause permanent or temporary hair loss, including hormonal changes due to pregnancy, childbirth, menopause and thyroid problems. Medical conditions include alopecia areata, which is autoimmune hair loss and causes patchy hair loss, scalp infections such as ringworm, and a hair-pulling disorder called trichotillomania (traction alopecia or traumatic alopecia).

- If your thyroid gland is overactive or underactive, your hair may fall out. This hair loss usually can be helped by treating your thyroid disease.

- Hair loss may occur if male or female hormones, known as androgens and estrogens, are out of balance. Correcting the hormone imbalance may stop your hair loss.

- Many women notice hair loss about 3 months after they’ve had a baby. This loss is also related to hormones. During pregnancy, high levels of certain hormones cause the body to keep hair that would normally fall out. When the hormones return to pre-pregnancy levels, that hair falls out and the normal cycle of growth and loss starts again.

- Certain infections can cause hair loss. Fungal infections of the scalp (tinea capitis) can cause hair loss in adults and children. The infection is treated with antifungal medicines.

- Systemic diseases resulting in reversible patchy hair thinning, poor hair quality and bald patches include:

- Diabetes

- Iron deficiency

- Thyroid hormone deficiency (hypothyroidism)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

- Syphilis

- Severe acute or chronic illness.

- Dermatological disease resulting in reversible patchy hair thinning, poor hair quality and bald patches include:

- Localized alopecia areata

- A localized infection, such as tinea capitis

- Severe local skin disease, such as psoriasis, seborrhoeic dermatitis, atopic dermatitis, pityriasis rubra pilaris, cutaneous lupus erythematosus, cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- Generalized skin disease (erythroderma).

- Medications and supplements. Hair loss can be a side effect of certain drugs, such as those used for cancer, arthritis, depression (antidepressants), birth control pills, vitamin A (if you take too much of it), heart problems, gout, blood thinners (anticoagulants) and high blood pressure. This type of hair loss improves when you stop taking the medicine.

- Radiation therapy to the head. The hair may not grow back the same as it was before.

- A very stressful event. Many people experience a general thinning of hair several months after a physical or emotional shock. This type of hair loss is temporary.

- Hairstyles and treatments. Excessive hairstyling or hairstyles that pull your hair tight, such as pigtails, cornrows or use tight hair rollers, the pull on your hair can cause a type of hair loss called traction alopecia. If the pulling is stopped before scarring of the scalp develops, your hair will grow back normally. However, scarring can cause permanent hair loss. Hot-oil hair treatments and chemicals used in permanents (also called “perms”) may cause inflammation (swelling) of the hair follicle cause the hair to fall out. If scarring occurs, hair loss could be permanent.

Hair loss can be subdivided into two main categories: scarring hair loss and non-scarring hair loss 40:

Non-scarring hair loss

Non-scarring hair loss falls into six major categories:

Androgenetic alopecia

Androgenetic alopecia is a pattern of hair loss that is affected by the genes and hormones (androgenic alopecia). Androgenetic alopecia is the most common form of hair loss in men and women and is a normal physiologic variant. Androgenetic alopecia is most prevalent in white men, with 30%, 40%, and 50% experiencing androgenetic alopecia at 30, 40, and 50 years of age, respectively (see Figure 1). Although androgenetic alopecia is less common in women, 38% of women older than 70 years may be affected (see Figure 2) 41. Androgenetic alopecia hair loss follows a gradual progressive course. Many patients with androgenetic alopecia have a family history of this condition. Hair thinning occurs in a sex-specific pattern.

Androgenic alopecia in men

Androgenic alopecia in men: bitemporal thinning of the frontal and vertex scalp, complete hair loss with some hair at the occiput and temporal fringes 42. Minoxidil and oral finasteride are the only treatments currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia. Both of these drugs stimulate hair regrowth in some men, but are more effective in preventing progression of hair loss. Although there are a number of other treatments listed in various texts, there is not good evidence to support their use 43. Topical minoxidil (2% or 5% solution) is approved for the treatment of androgenetic alopecia in men. Hair regrowth is more robust at the vertex than in the frontal area, and will take six to 12 months to improve 42. Treatment should continue indefinitely because hair loss reoccurs when treatment is discontinued. Adverse effects include irritant and contact dermatitis. Finasteride (Propecia), 1 mg per day orally, is approved to treat androgenetic alopecia in men for whom topical minoxidil has been ineffective. Adverse effects of finasteride include decreased libido, erectile dysfunction, and gynecomastia (increase in the amount of breast gland tissue in men) 44.

Androgenic alopecia in women

Androgenic alopecia in women: diffuse hair thinning of the vertex with sparing of the frontal hairline. Treatment involves topical minoxidil (2% solution). Adverse effects include irritant or contact dermatitis.

Alopecia areata

Alopecia areata also called autoimmune alopecia or autoimmune hair loss, is a common autoimmune skin disease, where your body’s immune system attacks your hair cells, causing patches of hair loss on the scalp, face and sometimes on other areas of your body 45. The term “alopecia” means hair loss and “areata” refers to the patchy nature of the hair loss that is typically seen with alopecia areata. Alopecia areata represent an attack on the hair roots by the body’s own immune system. Alopecia areata hair loss that can affect every part of the body, including the scalp, face, trunk, and extremities. When it affects only a portion of the body, it is called alopecia areata. When it affects an entire site, it is called alopecia totalis. When it involves the whole body, it is called alopecia universalis. The skin in these areas looks smooth. The cause is unknown, but it might be related to an autoimmune disease 46. The hair loss is usually fast, can happen at any age (mostly in young adults), and is more common in people with certain illnesses (such as diabetes and thyroid disease). In 80% of patients with a single bald patch, spontaneous regrowth occurs within a year. Even in the most severe cases of alopecia totalis and alopecia universalis, recovery may occur at some future date. This is an important difference between alopecia areata and the scarring forms of alopecia, which destroy the hair follicle and result in irreversible hair loss. Referral centers indicate that 34–50% of patients will recover spontaneously within 1 year, although most will experience multiple episodes of the alopecia, and 14–25% of patients will progress to alopecia totalis or alopecia universalis, from which full recovery is unusual (<10% of patients) 47.

Telogen effluvium

Telogen effluvium results from shifting of the hair cycle growth (anagen) phase towards the shedding (telogen) phase, you may lose 30 to 50 percent of your hair all at once. Clumps of hair come out in the shower or in hairbrush. Telogen effluvium is associated with physiologic or emotional stress. This stress may be a severe illness, injury, crash diet, or extreme mental stress. Your hair will usually grow back. Patients typically report significant hair loss and a decrease in hair volume (they commonly complain about their ponytail reducing in diameter) without well-defined alopecic patches. A pull test is typically positive 48. Telogen effluvium may result from an illness like hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) or hyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid). Also, it can arise from stress like major surgery. A crash diet, poor feeding, and drugs can cause telogen effluvium 49. Telogen effluvium is usually self-limited and resolves within two to six months. Treatment involves removing the underlying cause and providing reassurance about the reversible nature of hair loss.

Traumatic alopecia

This is similar to traction alopecia, which results from forceful traction of the hair commonly seen in children. Also, trichotillomania is a type of traumatic alopecia in which the patient pulls on his/her hair repeatedly 50.

Tinea capitis (ringworm of the scalp)

Tinea capitis is a fungal infection of the scalp and hair shafts (scalp ringworm). It is caused primarily by the dermatophyte species Microsporum and Trichophyton 51. The fungi can penetrate the hair follicle outer root sheath and ultimately may invade the hair shaft. Tinea capitis also causes round patches of hair loss. The skin in these areas looks dry, red, and scaly. There may be swollen lymph nodes at the back of the lower head. Clinically, tinea capitis divides into inflammatory and non-inflammatory types. The non-inflammatory type usually will not be complicated by scarring alopecia. The inflammatory type may result in a kerion (painful nodules with pus) as well as scarring alopecia 52. Tinea capitis, a highly contagious infection, occurs primarily in children between 3 and 14 years of age, but it might affect any age group. It may also involve the eyelashes and eyebrows. The signs and symptoms of ringworm of the scalp may vary, but it usually appears as itchy, scaly, bald patches on the head. Tinea capitis can is treatable with systemic antifungal medications because topical antifungals do not penetrate hair follicles. The treatment is for 4 to 8 weeks. Topical treatment is not recommended, as it is ineffective 53.

- Trichophyton species: oral terbinafine (Lamisil), itraconazole (Sporanox), fluconazole (Diflucan), or griseofulvin

- Microsporum species: griseofulvin

Anagen effluvium

Anagen effluvium is a sudden loss of 80 to 90 percent of your hair that occurs during the anagen phase (growing phase) of the cell cycle due to an event that impairs the mitotic or metabolic activity of the hair follicle. Anagen effluvium often happens in people with cancer who are receiving chemotherapy or it can be an inherited or congenital condition, such as loose anagen syndrome. Patients typically present with diffuse hair loss that begins days to weeks after exposure to a chemotherapeutic agent and is most apparent after one or two months 54. In cancer patients who are receiving chemotherapeutic agents, short broken hairs and empty hair follicles may be observed. The incidence of anagen effluvium after chemotherapy is approximately 65% 55; it is most commonly associated with cyclophosphamide, nitrosoureas, and doxorubicin (Adriamycin). Other causative medications include tamoxifen, allopurinol, levodopa, bromocriptine (Parlodel), and toxins such as bismuth, arsenic, and gold. Other medical and inflammatory conditions, such as mycosis fungoides or pemphigus vulgaris, can lead to anagen effluvium 56. Anagen effluvium is usually reversible, with regrowth one to three months after cessation of the offending agent. Permanent alopecia is rare. No pharmacologic intervention has been proven effective. A large meta-analysis of clinical trials concluded that scalp cooling was the only intervention that significantly reduced the risk of chemotherapy-induced anagen effluvium 57. However, scalp cooling should be discouraged because it may minimize delivery of chemotherapeutic drugs to the scalp, leading to cutaneous scalp metastases 57. Minoxidil may help during regrowth period.

Scarring hair loss

Scarring hair loss is divided into four major types:

Tinea capitis

Tinea capitis: the inflammatory variety of tinea capitis (favus) may culminate with scarring hair loss.

Alopecia mucinosa

Alopecia mucinosa also known as follicular mucinosis: Alopecia mucinosa is a benign condition that occurs when mucinous material accumulates in the hair follicles and the sebaceous glands. The mucinous material causes an inflammatory response that hinders the growth of hair.

Alopecia neoplastica

Alopecia neoplastica: This is the metastatic infiltration of the scalp hair with malignant cells.

Frontal fibrosing alopecia

Frontal fibrosing alopecia is a form of scarring hair loss affecting the hair margin on the front of the scalp (i.e. the forehead and sideburns). This happens due to inflammation and destruction of the hair follicles. There may also be hair loss from the scalp near the ears and from the eyebrows. Sometimes hair loss can also occur from other parts of the body, but this is less common. Frontal fibrosing alopecia occurs mostly in white postmenopausal women but can occur in premenopausal women, men, and people of other ethnicities. Frontal fibrosing alopecia is thought to be a variant of another condition called lichen planopilaris. There are a number of treatments that are used for frontal fibrosing alopecia to help to slow down or halt further hair loss in some people. Unfortunately, their success is variable and some people cannot find a treatment that is effective for them. Treatments used to slow the progression of the condition include oral corticosteroids, intralesional steroid injections, anti-inflammatory antibiotics such as tetracyclines, or anti-malarial tablets (hydroxychloroquine). All these treatments aim to lower the activity of the immune system and slow down the attack on the hair follicles.

Hair loss prevention

There is no way to prevent male-pattern baldness or female-pattern baldness (androgenetic alopecia), because it is a genetic trait, meaning you inherited a gene for baldness from your parents. This type of hair loss is not preventable.

Some other causes of excessive hair loss can be prevented. These tips may help you avoid preventable types of hair loss:

- Be gentle with your hair. Use a detangler and avoid tugging when brushing and combing, especially when your hair is wet. A wide-toothed comb might help prevent pulling out hair. Avoid harsh treatments such as hot rollers, curling irons, hot-oil treatments and permanents. Limit the tension on hair from styles that use rubber bands, barrettes and braids.

- Ask your doctor about medications and supplements you take that might cause hair loss.

- Protect your hair from sunlight and other sources of ultraviolet light.

- Stop smoking. Some studies show an association between smoking and baldness in men.

- If you’re being treated with chemotherapy, ask your doctor about a cooling cap. This cap can reduce your risk of losing hair during chemotherapy.

Hair loss diagnosis

Before making a diagnosis, your doctor will likely give you a physical exam and ask about your diet, your hair care routine, and your medical and family history. You might also have tests, such as the following:

- Blood test. This might help uncover medical conditions that can cause hair loss.

- Pull test. Your doctor gently pulls several dozen hairs to see how many come out. This helps determine the stage of the shedding process.

- Scalp biopsy. Your doctor scrapes samples from the skin or from a few hairs plucked from the scalp to examine the hair roots under a microscope. This can help determine whether an infection is causing hair loss.

- Light microscopy. Your doctor uses a special instrument to examine hairs trimmed at their bases. Microscopy helps uncover possible disorders of the hair shaft.

Best vitamins and supplements for hair growth

A variety of vitamins and supplements for hair growth have appeared in the market over the past few years 58, 8, 59. Several prior studies have demonstrated vitamins, omegas 3 and 6 fatty acids, and antioxidants promote hair growth, suggesting a role of adequate nutrition in hair growth and supporting the use of dietary supplements for hair loss 60, 61, 62.

Nutrafol

Nutrafol launched in 2016 and is currently the fastest growing nutraceutical supplement for hair growth on the market 59. Nutrafol is composed of 21 ingredients, including a proprietary Synergen Complex®, which includes standardized phytoactives with clinically tested anti-inflammatory, stress-adaptogenic, antioxidant and dihydrotestosterone (DHT)-inhibiting properties 59. The phytocompounds in this complex include curcumin, piperine, ashwagandha, saw palmetto, and tocotrienols 63, 64. In addition to the components detailed above, Nutrafol also contain amino acids, marine collagen, hyaluronic acid, organic kelp, and vitamins and minerals that have been identified to play a role in the stress response as well as gut, thyroid and hair health 64. There are currently four formulations available: Nutrafol Women, Nutrafol Women’s Balance, Nutrafol Postpartum, and Nutrafol Men, which has a higher concentration of saw palmetto.

Curcumin (a yellow pigment found primarily in turmeric) is a potent anti-inflammatory and immunomodulating agent that has been shown to inhibit NF-kb and decrease tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha and interleukin (IL)-1, inflammatory cytokines involved in follicular regression 64. Curcumin also inhibits androgen receptor expression, which is known to be overexpressed in follicles in androgenetic alopecia 65, 66. Co-administration with botanical piperine, found in black pepper and long pepper, enhances curcumin bioavailability and has been shown to increase plasma levels up to 154 percent after ingestion 64, 67. The stress response is known to play an important role in hair loss pathology and is intrinsically linked to alopecia areata (autoimmune hair loss) and telogen effluvium (hair loss associated with physiologic or emotional stress), with recent studies indicating that cortisol and micro-inflammation at the level of the hair follicle also plays a role in androgenic alopecia 68, 69.

Ashwagandha is a botanical that contains steroidal lactones which modulate and reduce cortisol levels. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of 98 patients, daily supplementation with 10% withanolide ashwaghanda showed statistically significant reductions in serum cortisol, serum C-reactive protein, blood pressure, and subjective feelings of stress compared to placebo 68. Saw palmetto extract is a natural inhibitor of both types I and II 5-alpha reductase which prevents conversion of testosterone to active DHT. A study of 100 men with mild to moderate androgenic alopecia who were treated with either 320 mg of saw palmetto or 1 mg of finasteride daily for two years revealed a significant improvement in 38 percent of patients taking saw palmetto and 68 percent of patients taking finasteride 70. Despite the increased efficacy of finasteride, saw palmetto might be a desirable alternative to avoid side effects of erectile dysfunction and falsely reducing prostate specific antigen (PSA) levels.5 While there are no reports of teratogenicity, saw palmetto is considered functionally related to finasteride, and therefore, it is considered unsafe in pregnancy. Vitamin E isoforms consist of four tocopherols and four tocotrienols, which are potent free radical scavengers 64. A randomized, placebo-controlled study of 38 patients with hair loss showed a statistically significant increase in hair counts of 38 percent from baseline compared to placebo 71. The authors concluded that the effect was most likely due to antioxidant activity, inhibition of lipid peroxidation, and oxidative stress in the scalp 71, 72.

The efficacy of Nutrafol to promote hair growth was studied in a six-month randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Forty healthy women between the ages of 21 and 65 years old with self-perceived hair thinning were randomized into two groups, with 26 subjects receiving four capsules of Nutrafol daily and 14 subjects receiving placebo. The number of terminal and vellus hairs was analyzed based on phototrichograms of a 1 cm² area along the frontalis bone at Day 0, Day 90, and Day 180. Subjects taking Nutrafol showed an increased terminal hair count of 6.8 percent and 10.4 percent at 90 and 180 days, respectively, compared to 0.07 percent and 3.5 percent in the placebo group 64. Vellus hair counts increased by 10.1 percent and 15.7 percent at days 90 and 180 in the Nutrafol group compared to a decrease in vellus hair counts of 2.9 percent and 2.2 percent at days 90 and 180 in the placebo group 73. There was no statistically significant difference in mean hair shaft diameter between treatment and placebo groups at any point in the study 73. Investigator scores for hair growth and hair quality increased significantly from baseline to day 180. Eighty percent of subjects in the Nutrafol group reported a significant improvement in hair growth compared with 46.2 percent of placebo-treated subjects. Subjects taking Nutrafol also reported improvement in overall hair volume, noticeable new hair, hair growth rate, stress and anxiety levels, sleep quality, skin smoothness and skin health 73. The majority of subjects taking Nutrafol (73.1%) would recommend it to friends with hair loss.

A recent case series demonstrated clinical improvement in four subjects taking Nutrafol as a monotherapy 64. A 52-year-old woman who had previously failed a several month course of topical minoxidil showed increased hair density after seven months. A 45-year-old woman with early signs of diffuse pattern hair loss showed improved hair density after four months. A 37-year-old man with early pattern hair loss and a strong family history of hair loss who had previously failed minoxidil showed improved hair growth and decreased shedding. Lastly, a 38-year-old woman with early diffuse thinning of the temple areas experienced increased density after three months of daily Nutrafol use. No patient reported any side effects, and all were satisfied with their improvement 59.

Viviscal

Viviscal® is an oral supplement based on a novel marine complex formulation designed to promote hair growth in both men and women 74, 75. The key ingredients in Viviscal include a proprietary blend of shark and mollusk powder derived from sustainable marine sources (AminoMar® C marine complex), Equisteum arvense (natural occurring form of silica), Malpighia glabra (acerola cherry providing vitamin C), biotin (vitamin B7), and zinc. Other ingredients include calcium, iron, horsetail stem extract, millet seed extract, flaxseed extract, procyanidin B-2 (i.e., apple fruit extract), L-cystine and L-methionine, depending on the formulation. In addition to the original formulation, other formulations include Viviscal® Professional Strength and Viviscal® Man. Early studies evaluating a similar oral formulation of marine extracts in women with photodamaged skin demonstrated improvements in skin thickness, elasticity and erythema, as well as improvements in hair and nail brittleness after 90 days of treatment 76, 77. Following an initial open-label pilot study, several randomized, placebo-controlled trials have demonstrated the current oral marine complex supplement to be effective in promoting hair growth in both men and women 75, 78, 79, 80.

In the first randomized-controlled trial, 15 healthy women with Fitzpatrick Skin Types I to IV and self-perceived hair thinning were randomized to receive the Viviscal® Maximum Strength oral supplement or placebo twice daily for 180 days 79. A 2 cm² area of the scalp was selected for hair counts, which were performed at baseline and after 90 and 180 days of treatment. Mean number of terminal hairs in the treatment group increased from 271.0 to 571 and 609.6 at 90 and 180 days, respectively. In contrast, the mean number of terminal hairs in the placebo group decreased at 90 and 180 days. The mean number of vellus hairs did not significantly change in either group. After 90 days, more subjects in the treatment group reported improvements in overall hair volume, scalp coverage and hair thickness. Additional improvements noted at 180 days in the treatment group included increased hair shine, skin moisture retention, and skin smoothness. No adverse events were reported.

In another double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, 60 healthy women with Fitzpatrick Skin Types I to IV with self-perceived hair thinning were randomized to receive either the Viviscal® Extra Strength oral supplement or placebo twice daily for 90 days 75. Similar to the prior study, a predesignated 4 cm² area of the scalp was selected for evaluation at baseline and after 90 days. Additionally, ten terminal hairs in the target area were chosen and cut at the surface of the scalp to evaluate hair growth. Digital photographs were obtained to measure hair diameter and the diameter for ten hairs was used to obtain the mean hair diameter within the target area. At 90 days, there was a significant increase in mean number of terminal hairs from 178.3 to 235.8 in the treatment group compared to a smaller increase of 178.2 to 180.9 in the placebo group. The number of vellus hairs also increased in the treatment group from 19.6 to 21.2 compared to 19.8 to 19.9 in the placebo group. A significant decrease in the mean number of shed hairs from 27.1 to 16.5 was also observed in the treatment group (vs. 23.4 to 21.9 in the placebo group). No significant change in terminal hair diameter was observed in either group. In addition to the improvements in objective measures observed, subjects in the treatment group also had higher scores on a self-assessment questionnaire that rated overall hair quality including hair growth, hair volume, hair thickness, hair strength, eyebrow hair growth and scalp coverage as well as overall skin health. No adverse events were reported.

A subsequent double-blind, placebo-controlled trial evaluated the efficacy of the Viviscal® Professional Strength Oral Tablets, an oral formulation of the marine supplement containing procyanidin B-2 (i.e., apple fruit extract), L-cystine and L-methionine for the treatment of hair loss in women 81. Forty healthy women with Fitzpatrick Skin Types I to IV and with self-perceived hair thinning were randomly assigned to receive either the oral supplement or placebo twice daily for 180 days 81. A predesignated target area on the scalp was assessed using phototrichogram analysis to determine change in number of terminal and vellus hairs at 180 days. Terminal hair diameter and response scores to quality of life and self-assessment questionnaires were also evaluated. In the treatment group, the mean number of terminal hairs increased from 189.9 to 297.4 and 341.0 at 90 and 180 days, respectively, and mean number of vellus hairs increased from 19.9 to 20.2 and 22.8 at 90 and 180 days, respectively. Mean hair diameter also significantly improved in the treatment group from 0.06 mm to 0.07 mm and 0.067 mm at 90 and 180 days, respectively, which had not been found in previous studies of the prior formulation. There were no significant improvements in any of these parameters in the placebo group. Subjects in the treatment group reported greater scores on the quality of life and self-assessment questionnaires compared to the placebo group, indicating greater improvements in overall hair volume, scalp coverage, hair strength, nail strength, eyelash growth, skin smoothness, and overall skin health.

In another study, 96 healthy women with Fitzpatrick Skin Types I to III and self-perceived hair thinning were randomly assigned to receive the Viviscal® Oral Supplement or placebo three times daily for 180 days 78. The aim of this study was to add to the results of the initial double-blind, placebo-controlled trial by evaluating shed hair count analysis and hair diameter analysis using a phototrichogram. A predesignated area of the scalp was selected for two-dimensional digital images and trichoanalysis, which was performed at baseline, 90 days and 180 days. Shed hair was collected during shampooing and counted at each visit. Overall, mean hair shedding was significantly reduced in the treatment group from 52.1 to 42.6 and 42.7 at 90 and 180 days, respectively. In the placebo group, an initial increase in mean hair shedding was seen at 90 days, followed by a small decrease at 180 days. Mean vellus hair diameter showed a small but significant increase in the treatment group at 90 and 180 days, but no change was observed in the placebo group at either time point.

The studies discussed thus far consistently demonstrated the effectiveness of Viviscal® in promoting hair growth in women with self-perceived hair thinning 59. However, the efficacy of the oral supplement in men with hair loss had not yet been evaluated. In a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, Ablon 80 evaluated the efficacy of Viviscal® Man, a reformulation of the original marine complex supplement for use in men. Sixty healthy men with clinically diagnosed male pattern hair loss were randomized to receive the reformulated supplement or placebo twice daily for 180 days 80. A predesignated target area on the midline scalp was chosen for two-dimensional digital images and trichoanalysis at baseline, 90 days and 180 days. A hair pull test on the right and left parietal, frontal and occipital scalp was also performed at baseline and 180 days. After treatment, subjects in the treatment group experienced significant improvement in all efficacy measures. Mean total hair increased from 162.2 to 169.1 and 174.9 at 90 and 180 days, respectively, total hair density increased from 159.7 to 166.5 and 172.2 at 90 and 180 days, respectively, and terminal hair density increased from 121.9 to 127.7 and 130.3 at 90 and 180 days, respectively 80. The hair pull test was also significantly improved in the treatment group at 180 days. No improvements in any of these parameters were observed in the placebo group. Subjects in the treatment group also reported significant improvements in several quality of life measures and self-assessment items including overall hair growth, hair volume, hair and nail strength, and overall skin healthy. No adverse events were reported.

Based on the current literature, Viviscal® appears to be effective in promoting hair growth and decreasing hair shedding in both men and women 80, 75, 81. Studies have also demonstrated that Viviscal® may offer the additional benefit of subjective improvements in the appearance and quality of the skin, nails and eyebrows 80, 81, 79. Theories behind the benefit of Viviscal® primarily involve providing adequate nutrition and vitamins that promote hair growth, as inadequate nutrition and various vitamin deficiencies have been associated with hair loss 82.

Advantages of Viviscal over current pharmaceutical therapies, such as topical minoxidil and oral finasteride, include additional improvements to skin and nail health and a more favorable side effect profile. In all of the studies performed thus far, no significant adverse events associated with the oral supplement have been reported 59. Therefore, Viviscal would likely be appropriate to use in the majority of patients. This is in contrast to many of the current pharmaceutical treatments for hair loss, such as topical minoxidil, which may cause local irritation at the application site, or oral finasteride, which has been associated in rare instances with sexual dysfunction in men and is often not favorable to use in women. Several Viviscal formulations contain biotin (vitamin B7), which may be a cause for concern. Recently, the FDA issued a warning that biotin might interfere with certain laboratory testing results, including endocrine and cardiovascular laboratory tests 83, 84. Given this warning, patients taking Viviscal® regularly should be aware of this possibility. However, Viviscal supplement contains about 100 to 240 micrograms of biotin compared to 5,000 micrograms found in most biotin supplements, which might have a smaller impact on laboratory tests compared to supplements containing higher amounts of biotin. Of note, the formulation for men does not contain any biotin 59.

Nourkrin

Nourkrin® is a newly developed hair growth product containing marine proteins extract, vitamins, minerals, acerola cherry extract, silica kieselguhr, horsetail extract and immunoglobulins 85. The active ingredients in Nourkrin are meant tonourish the hair follicles and ‘awaken’ the dormant hair follicles, thereby stopping hairloss, stimulating regrowth of new hair and strengthening the existing hair 85. However, the mechanism of action of Nourkrin is not known, but it might be related to the production of dihydrotestosterone (DHT) in the hair follicle. Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) is known to cause hair loss. Studies have been initiated to investigate this aspect. Nourkrin has been shown, in open pilot studies carried out as part of the product development process, to have a favourable effect on hair loss 85. In a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study involving 60 subjects (55 males and 4 females [there were 5/60 (8.3%) withdrawals/losses to follow‐up: 3/30 (10%) in Nourkrin® group, 2/30 (6.7%) placebo group]) taking 2 capsules/day (< 80 kg in body weight) or 3 capsules/day (> 80 kg) for 6 months, the average hair growth increase was 35.7% in the group using Nourkrin and 1.5% in the placebo group 85, The results of this study show that the subjects reported favourable effects on hair gain with Nourkrin® compared with placebo and the same effect was also detectable in the open long-term (6 months or more) study.

The results obtained in the present study compare favourably with results obtained in studies with the drugs minoxidil and finasteride 85. The positive effect of Nourkrin combined with its excellent tolerability may make this product an attractive alternative treatment for people with hair-loss problems.

Biotin (vitamin B7)

Biotin also known as vitamin B7 or vitamin H, is a B-complex water-soluble vitamin that helps turn the carbohydrates, fats, and proteins in the food you eat into the energy you need 86. Biotin (vitamin B7) is a cofactor for five carboxylase enzymes (propionyl-CoA carboxylase, pyruvate carboxylase, methylcrotonyl-CoA carboxylase [MCC], acetyl-CoA carboxylase 1, and acetyl-CoA carboxylase 2) that catalyze critical steps in fatty acid synthesis, amino acid catabolism, gluconeogenesis, and mitochondrial function in hair root cells 87, 88, 89. Biotin also plays key roles in histone modifications, gene regulation (by modifying the activity of transcription factors), and cell signaling 88.

Foods that contain the most biotin include organ meats, eggs, fish, meat, seeds, nuts, and certain vegetables (such as sweet potatoes) 89. The biotin content of food can vary; for example, plant variety and season can affect the biotin content of cereal grains, and certain processing techniques (e.g., canning) can reduce the biotin content of foods 90. Although overt biotin deficiency is very rare 91, 90 and severe biotin deficiency in healthy individuals eating a normal mixed diet has never been reported 92. The human requirement for dietary biotin has been demonstrated in three different situations: prolonged intravenous feeding (parenteral) without biotin supplementation, infants fed an elemental formula devoid of biotin, and consumption of raw egg white for a prolonged period (many weeks to years) 93.

The signs and symptoms of biotin deficiency typically appear gradually and can include thinning hair with progression to loss of all hair on the body; scaly, red rash around body openings (eyes, nose, mouth, and genital area); conjunctivitis; ketolactic acidosis (which occurs when lactate production exceeds lactate clearance) and aciduria (abnormal amounts of acid in urine); seizures; skin infection (candidiasis); brittle nails; neurological findings (e.g., depression, lethargy, hallucinations, ataxia and numbness and tingling of the extremities) in adults; and hypotonia, lethargy, hearing loss, vision loss and developmental delay in infants, older children and adolescents 94, 89, 88, 92. Once vision problems, hearing loss, and developmental delay occur, they are usually irreversible, even with biotin therapy 94. The rash and unusual distribution of facial fat in people with biotin deficiency is known as “biotin deficiency facies” 95, 92. Individuals with hereditary disorders of biotin metabolism resulting in functional biotin deficiency often have similar physical findings, as well as seizures and evidence of impaired immune system function and increased susceptibility to bacterial and fungal infections 96, 97.

Therefore, biotin supplements are often promoted for hair, skin, and nail health. However, these claims are supported, at best, by only a few case reports and small studies. Only case reports are available to support claims that biotin supplements can promote hair health, and these reports were only in children 98, 99. These studies found that 3–5 mg/day biotin in children with uncombable hair syndrome (a rare disorder of the hair shaft) significantly improved hair health after 3–4 months. The evidence supporting the use of biotin supplements to support skin health is equally limited to a small number of case reports, all in infants, showing that 100 mcg to 10 mg/day resulted in dramatic improvements in rash or dermatitis as well as hair loss 100, 101.

Biotin deficiency (< 100 ng/L) and suboptimal biotin levels (100–400 ng/L) were reported in 38% and 49% of healthy women complaining of hair loss, respectively. However, 11% of these patients were later found to have a secondary cause for low biotin levels, including use of antiepileptics, isotretinoin, antibiotics, or gastrointestinal disease altering the biotin-producing gut microflora 102.

Although highly popularized in the media for its beneficial effects on hair loss, there have been no randomized controlled trials to evaluate the effect of biotin supplementation in hair loss 103. Patients taking isotretinoin or valproic acid have decreased biotinidase levels, the enzyme responsible for releasing biotin from food. As a result, isotretinoin-associated telogen effluvium and alopecia secondary to valproic acid may benefit from biotin supplementation 104, 105. A recent review identified 11 cases of hair loss secondary to biotin deficiency, from either an inherited enzyme deficiency or medication, where biotin was an effective supplementation for hair regrowth 106. Current clinical evidence supports biotin supplementation as an effective therapy for hair loss only in cases secondary to biotin deficiency; however, apart from medications, this is rare in developed countries due to well-balanced dietary intake 86.