What is chronic pain syndrome

Chronic pain syndrome is pain that lasts more than several months (variously defined as 3 to 6 months, but longer than “normal healing”) 1, 2, 3, 4. Common chronic pain syndrome include headache, low back pain, cancer pain, arthritis pain, neurogenic pain (pain resulting from damage to the peripheral nerves or to the central nervous system itself), psychogenic pain (pain not due to past disease or injury or any visible sign of damage inside or outside the nervous system). A person may have two or more co-existing chronic pain conditions, several of which cause pain, may occur together. Such conditions can include chronic fatigue syndrome, endometriosis, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, interstitial cystitis (painful bladder syndrome), temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and vulvodynia (chronic vulvar pain). It is not known whether these disorders share a common cause. Distress, demoralization and functional impairment often accompany chronic pain syndrome, making it a major source of suffering and economic burden 5. Pain is a signal in your nervous system that something may be wrong. Pain is an unpleasant feeling, such as a prick, tingle, sting, burn, or ache. Pain may be sharp or dull. You may feel pain in one area of your body, or all over. There are two types: acute pain and chronic pain. Acute pain lets you know that you may be injured or a have problem you need to take care of. Chronic pain is different. The pain may last for weeks, months, or even years. The original cause may have been an injury or infection. There may be an ongoing cause of pain, such as arthritis or cancer. In some cases there is no clear cause. Environmental and psychological factors can make chronic pain worse.

Chronic pain syndrome is a very common problem. Results from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey show that:

- About 25.3 million U.S. adults (11.2 percent) had pain every day for the previous 3 months 6.

- Nearly 40 million adults (17.6 percent) had severe pain.

- Chronic pain syndrome is reported more commonly in women.

- Chronic pain affects 20% of people worldwide 7.

- Individuals with severe pain had worse health, used more health care, and had more disability than those with less severe pain.

- Chronic pain becomes more common as people grow older, at least in part because health problems that can cause pain, such as osteoarthritis, become more common with advancing age. Military veterans are another group at increased risk for chronic pain; U.S. national survey data show that both pain in general and severe pain are more common among veterans than nonveterans.

Not all people with chronic pain syndrome have a health problem diagnosed by a health care provider, but among those who do, the most frequent conditions by far are low-back pain or osteoarthritis, according to a national survey. Other common diagnoses include rheumatoid arthritis, migraine, carpal tunnel syndrome, and fibromyalgia. The annual economic cost of chronic pain in the United States, including both treatment and lost productivity, has been estimated at up to $635 billion.

Chronic pain syndrome may result from an underlying disease or health condition, an injury, medical treatment (such as surgery), inflammation, or a problem in the nervous system (in which case it is called “neuropathic pain”); or the cause may be unknown. Pain can affect quality of life and productivity, and it may be accompanied by difficulty in moving around, disturbed sleep, anxiety, depression, and other problems 8.

The decision to perform any laboratory or imaging evaluations is based on the need to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out other potentially life-threatening illnesses. Sometimes certain investigations are needed to provide appropriate and safe medical or surgical treatment. The recommended treatment should be based on clinical findings or changes in examination findings.

Imaging studies, including with radiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) scanning, are important tools in the workup of patients with chronic pain syndrome.

Chronic pain syndrome is a constellation of syndromes that usually do not respond to the medical model of care. Chronic pain syndrome is not always curable, but treatments can help. Chronic pain syndrome is managed best with a multidisciplinary approach, requiring good integration and knowledge of multiple organ systems. Medications, acupuncture, local electrical stimulation, and brain stimulation, as well as surgery, are some treatments for chronic pain syndrome. Some physicians use placebos, which in some cases has resulted in a lessening or elimination of pain. Psychotherapy, relaxation and medication therapies, biofeedback, and behavior modification may also be employed to treat chronic pain syndrome.

Chronic pain syndrome classification (ICD 11)

Chronic pain was defined as persistent or recurrent pain lasting longer than 3 months. This definition according to pain duration has the advantage that it is clear and operationalized 9, 1.

Optional specifiers for each diagnosis record evidence of psychosocial factors and the severity of the pain. Pain severity can be graded based on pain intensity, pain-related distress, and functional impairment.

Table 1. Chronic Pain Syndrome Classification

| Pain Type | Definition | Neurobiologic Mechanism | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chronic Primary Pain | |||

| 1. Chronic widespread pain | Widespread pain persisting for longer than 3 months, associated with emotional distress or functional disability | Central sensitization | Fibromyalgia |

| 2. Complex Regional Pain Syndrome (CRPS) | Disorder of body region, usually distal limbs, characterized by pain (allodynia), swelling, loss of function, vasomotor instability, skin changes | Neuropathic Central sensitization | Chronic Regional Pain Syndrome (formerly reflex sympathetic dystrophy) |

| 3. Chronic primary headache or orofacial pain | Idiopathic headache or orofacial pain, not secondary to another condition | Nociceptive Neuropathic Central sensitization | Chronic migraine or temporomandibular disorder |

| 4. Chronic primary visceral pain | Persistent or recurrent pain originating from internal organs, without a clear organic cause | Central sensitization | Irritable bowel syndrome |

| 5. Chronic primary musculoskeletal pain | Chronic pain experienced in muscles, bones, joints, or tendons that cannot be attributed directly to a known disease or tissue damage process 10 | Nociceptive Neuropathic Central sensitization | Non-specific low back pain |

| Chronic Secondary Pain | |||

| 1. Chronic cancer-related pain | Pain caused by the cancer itself (by the primary tumor or by metastases) or by its treatment (surgery, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy) 11 | Nociceptive Neuropathic Central sensitization | Chronic cancer pain, chronic cancer treatment pain (eg, chemotherapy-induced peripheral neuropathy, radiation fibrosis) |

| 2. Chronic postsurgical or posttraumatic pain | Pain secondary to surgery or trauma which persists for longer than 3 months | Nociceptive Neuropathic Central sensitization | Incisional pain, nerve injury due to trauma or surgery (eg, persistent whiplash or low back pain after trauma) |

| 3. Chronic neuropathic pain | Pain caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system 12 | Neuropathic | Trigeminal neuralgia, chronic painful polyneuropathy (eg, diabetic polyneuropathy), postherpetic neuralgia |

| 4. Chronic secondary headache or orofacial pain | Headaches or orofacial pains, secondary to a medical condition | Nociceptive Neuropathic Central sensitization | Head/face pain secondary to trauma, tumor, hemorrhage, etc. |

| 5. Chronic secondary visceral pain | Persistent or recurrent pain originating from internal organs, due to a secondary cause | Nociceptive | Abdominal pain due to adhesions or ischemia |

| 6. Chronic secondary musculoskeletal pain | Persistent or recurrent pain that arises as part of a disease process directly affecting bones, joints, muscles, or related soft tissues | Nociceptive | Rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis |

Chronic primary pain

Chronic primary pain is pain in 1 or more anatomic regions that persists or recurs for longer than 3 months and is associated with significant emotional distress or significant functional disability (interference with activities of daily life and participation in social roles) and that cannot be better explained by another chronic pain condition. Chronic primary pain is characterized by disability or emotional distress and not better accounted for by another diagnosis of chronic pain. Here, you will find chronic widespread pain, chronic musculoskeletal pain previously termed “non-specific” as well as the primary headaches and conditions such as chronic pelvic pain and irritable bowel syndrome. This is a new phenomenological definition, created because the cause is unknown for many forms of chronic pain. Common conditions such as, for example, back pain that is neither identified as musculoskeletal or neuropathic pain, chronic widespread pain, fibromyalgia, and irritable bowel syndrome will be found in this section and biological findings contributing to the pain problem may or may not be present. The term “primary pain” was chosen in close liaison with the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) of the World Health Organization (WHO) ICD-11 revision committee, who felt this was the most widely acceptable term, in particular, from a nonspecialist perspective.

Chronic secondary pain

Chronic secondary pain syndromes are linked to other diseases as the underlying cause, for which pain may initially be regarded as a symptom. The proposed new International Classification of Diseases 11 (ICD-11) codes become relevant as a codiagnosis, when this symptom requires specific care for the patient. This marks the stage when the chronic pain becomes a problem in its own right. In many cases, the chronic pain may continue beyond successful treatment of the initial cause; in such cases, the pain diagnosis will remain, even after the diagnosis of the underlying disease is no longer relevant. It is expected that this new coding will facilitate treatment pathways for patients with these painful conditions by recognizing the chronic pain problem early in the course of the disease. This is also important if the underlying disease is painful in only some of the patients; disease diagnosis alone does not identify these patients without the codiagnosis of chronic pain.

Chronic secondary pain is organized into the following six categories:

Chronic cancer pain

Chronic cancer pain includes pain caused by the cancer itself (the primary tumor or metastases) and pain that is caused by the cancer treatment (surgical, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and others) 13, 14. Cancer-related pain will be subdivided based on location into visceral, bony (or musculoskeletal), and somatosensory (neuropathic). It will be described as either continuous (background pain) or intermittent (episodic pain) if associated with physical movement or clinical procedures 15.

Pain is a frequent and debilitating accompaniment of cancer and its treatment 16. It becomes more and more apparent that chronic pain syndromes are prevalent in long-term survivors of cancer, and that these chronic secondary pain syndromes include neuropathic and musculoskeletal pains 17. Chronic pain caused by the cancer or by chemotherapy or radiation therapy is coded in this section. Pain that is caused by surgical cancer treatment is coded in the section of chronic postsurgical pain.

Chronic postsurgical and posttraumatic pain

Because pain that persists beyond normal healing is frequent after surgery and some types of injuries, the entity of postsurgical and posttraumatic pain was created. This is defined as pain that develops after a surgical procedure or a tissue injury (involving any trauma, including burns) and persists at least 3 months after surgery or tissue trauma 18; this is a definition of exclusion, as all other causes of pain (infection, recurring malignancy) as well as pain from a pre-existing pain problem need to be excluded. In view of the different causality, as well as from a medicolegal point of view, a separation between postsurgical pain and pain after all other trauma is regarded as useful. Depending on the type of surgery, chronic postsurgical pain is often neuropathic pain (on average 30% of cases with a range from 6% to 54% and more) 19. Pain including such a neuropathic component is usually more severe than nociceptive pain and often affects the quality of life more adversely 20.

Chronic neuropathic pain

Chronic neuropathic pain is caused by a lesion or disease of the somatosensory nervous system 21. The somatosensory nervous system provides information about the body including skin, musculoskeletal, and visceral organs. Neuropathic pain may be spontaneous or evoked, as an increased response to a painful stimulus (hyperalgesia) or a painful response to a normally nonpainful stimulus (allodynia). The diagnosis of neuropathic pain requires a history of nervous system injury, for example, by a stroke, nerve trauma, or diabetic neuropathy, and a neuroanatomically plausible distribution of the pain 21. For the identification of definite neuropathic pain, it is necessary to demonstrate the lesion or disease involving the nervous system, for example, by imaging, biopsy, neurophysiological, or laboratory tests. In addition, negative or positive sensory signs compatible with the innervation territory of the lesioned nervous structure must be present 22. Diagnostic entities within this category will be divided into conditions of peripheral or central neuropathic pain.

Chronic headache and orofacial pain

The International Headache Society has created a headache classification 23 that is implemented in full in the chapter on neurology. This classification differentiates between primary (idiopathic), secondary (symptomatic) headache, and orofacial pain including cranial neuralgias. In the section on chronic pain, only chronic headache and chronic orofacial pain will be included. Chronic headache and chronic orofacial pain is defined as headaches or orofacial pains that occur on at least 50% of the days during at least 3 months. For most purposes, patients receive a diagnosis according to the headache phenotypes or orofacial pains that they currently present. The section will list the most frequent chronic headache conditions.

The most common chronic orofacial pains are temporomandibular disorders 24, which have been included in this subchapter of chronic pain. Chronic orofacial pain can be a localized presentation of a primary headache.2 This is common in the trigeminal autonomic cephalalgias, less common in migraines, and rare in tension-type headache. Several chronic orofacial pains such as post-traumatic trigeminal neuropathic pain,3 persistent idiopathic orofacial pain, and burning mouth syndrome are cross-referenced to, eg, primary chronic pain and neuropathic pain. The temporal definition of “chronic” has been extrapolated from that of chronic headaches 25.

Chronic visceral pain

Chronic visceral pain is persistent or recurrent pain that originates from the internal organs of the head and neck region and the thoracic, abdominal, and pelvic cavities 26. The pain is usually perceived in the somatic tissues of the body wall (skin, subcutis, muscle) in areas that receive the same sensory innervation as the internal organ at the origin of the symptom (referred visceral pain) 27. In these areas, secondary hyperalgesia (increased sensitivity to painful stimuli in areas other than the primary site of the nociceptive input) often occurs30; the intensity of the symptom may bear no relationship with the extent of the internal damage or noxious visceral stimulation 28. The section on visceral pain will be subdivided according to the major underlying mechanisms, ie, persistent inflammation, vascular mechanisms (ischemia, thrombosis), obstruction and distension, traction and compression, combined mechanisms (eg, obstruction and inflammation concurrently), and referral from other locations. Pain due to cancer will be cross-referenced to the chapter chronic cancer pain and pain due to functional or unexplained mechanisms to chronic primary pain.

Chronic musculoskeletal pain

Chronic musculoskeletal pain is defined as persistent or recurrent pain that arises as part of a disease process directly affecting bone(s), joint(s), muscle(s), or related soft tissue(s). This category is limited to nociceptive pain and does not include pain that may be perceived in musculoskeletal tissues but does not arise therefrom, such as the pain of compression neuropathy or somatic referred pain. The entities subsumed in this approach include those characterized by persistent inflammation of infectious, autoimmune or metabolic etiology, such as rheumatoid arthritis, and by structural changes affecting bones, joints, tendons, or muscles, such as symptomatic osteoarthrosis. Musculoskeletal pain of neuropathic origin will be cross-referenced to neuropathic pain. Well-described apparent musculoskeletal conditions for which the causes are incompletely understood, such as nonspecific back pain or chronic widespread pain, will be included in the section on chronic primary pain.

Chronic pain syndrome vs Fibromyalgia

Fibromyalgia is a chronic pain disorder that causes musculoskeletal pain accompanied by fatigue, sleep, memory and mood issues. People with fibromyalgia have “tender points” on the body. Tender points are specific places on the neck, shoulders, back, hips, arms, and legs. These points hurt when pressure is put on them.

Fibromyalgia symptoms sometimes begin after a physical trauma, surgery, infection or significant psychological stress. In other cases, symptoms gradually accumulate over time with no single triggering event.

Anyone can get it, but women are more likely to develop fibromyalgia than are men. Many people who have fibromyalgia also have tension headaches, temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, irritable bowel syndrome, anxiety and depression.

While there is no cure for fibromyalgia, a variety of medications can help control symptoms. Exercise, relaxation and stress-reduction measures also may help.

Symptoms of fibromyalgia include:

- Widespread pain. The pain associated with fibromyalgia often is described as a constant dull ache that has lasted for at least three months. To be considered widespread, the pain must occur on both sides of your body and above and below your waist.

- Fatigue. People with fibromyalgia often awaken tired, even though they report sleeping for long periods of time. Sleep is often disrupted by pain, and many patients with fibromyalgia have other sleep disorders, such as restless legs syndrome and sleep apnea.

- Cognitive difficulties. A symptom commonly referred to as “fibro fog” impairs the ability to focus, pay attention and concentrate on mental tasks.

People with fibromyalgia may also have other symptoms, such as:

- Trouble sleeping

- Morning stiffness

- Headaches

- Painful menstrual periods

- Tingling or numbness in hands and feet

- Problems with thinking and memory (sometimes called “fibro fog”)

Fibromyalgia often co-exists with other painful conditions, such as:

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Migraine and other types of headaches

- Interstitial cystitis or painful bladder syndrome

- Temporomandibular joint disorders

No one knows what causes fibromyalgia. Researchers believe that fibromyalgia amplifies painful sensations by affecting the way your brain processes pain signals. People with rheumatoid arthritis and other autoimmune diseases are particularly likely to develop fibromyalgia. There is no cure for fibromyalgia, but medicine can help you manage your symptoms. Getting enough sleep, exercising, and eating well may also help.

Fibromyalgia causes

Doctors don’t know what causes fibromyalgia, but it most likely involves a variety of factors working together. These may include:

- Genetics. Because fibromyalgia tends to run in families, there may be certain genetic mutations that may make you more susceptible to developing the disorder.

- Infections. Some illnesses appear to trigger or aggravate fibromyalgia.

- Physical or emotional trauma. Fibromyalgia can sometimes be triggered by a physical trauma, such as a car accident. Psychological stress may also trigger the condition.

Researchers believe repeated nerve stimulation causes the brains of people with fibromyalgia to change. This change involves an abnormal increase in levels of certain chemicals in the brain that signal pain (neurotransmitters). In addition, the brain’s pain receptors seem to develop a sort of memory of the pain and become more sensitive, meaning they can overreact to pain signals.

Risk factors for fibromyalgia

Risk factors for fibromyalgia include:

- Your sex. Fibromyalgia is diagnosed more often in women than in men.

- Family history. You may be more likely to develop fibromyalgia if a relative also has the condition.

- Other disorders. If you have osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis or lupus, you may be more likely to develop fibromyalgia.

Fibromyalgia complications

The pain and lack of sleep associated with fibromyalgia can interfere with your ability to function at home or on the job. The frustration of dealing with an often-misunderstood condition also can result in depression and health-related anxiety.

Fibromyalgia diagnosis

In the past, doctors would check 18 specific points on a person’s body to see how many of them were painful when pressed firmly. Newer guidelines don’t require a tender point exam. Instead, a fibromyalgia diagnosis can be made if a person has had widespread pain for more than three months — with no underlying medical condition that could cause the pain.

Blood tests

While there is no lab test to confirm a diagnosis of fibromyalgia, your doctor may want to rule out other conditions that may have similar symptoms. Blood tests may include:

- Complete blood count (CBC)

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR)

- Cyclic citrullinated peptide test

- Rheumatoid factor

- Thyroid function tests

Fibromyalgia treatment

In general, treatments for fibromyalgia include both medication and self-care. The emphasis is on minimizing symptoms and improving general health. No one treatment works for all symptoms.

Medications

Medications can help reduce the pain of fibromyalgia and improve sleep. Common choices include:

- Pain relievers. Over-the-counter pain relievers such as acetaminophen (Tylenol, others), ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others) or naproxen sodium (Aleve, others) may be helpful. Your doctor might suggest a prescription pain reliever such as tramadol (Ultram). Narcotics are not advised, because they can lead to dependence and may even worsen the pain over time.

- Antidepressants. Duloxetine (Cymbalta) and milnacipran (Savella) may help ease the pain and fatigue associated with fibromyalgia. Your doctor may prescribe amitriptyline or the muscle relaxant cyclobenzaprine to help promote sleep.

- Anti-seizure drugs. Medications designed to treat epilepsy are often useful in reducing certain types of pain. Gabapentin (Neurontin) is sometimes helpful in reducing fibromyalgia symptoms, while pregabalin (Lyrica) was the first drug approved by the Food and Drug Administration to treat fibromyalgia.

Therapy

A variety of different therapies can help reduce the effect that fibromyalgia has on your body and your life. Examples include:

- Physical therapy. A physical therapist can teach you exercises that will improve your strength, flexibility and stamina. Water-based exercises might be particularly helpful.

- Occupational therapy. An occupational therapist can help you make adjustments to your work area or the way you perform certain tasks that will cause less stress on your body.

- Counseling. Talking with a counselor can help strengthen your belief in your abilities and teach you strategies for dealing with stressful situations.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Self-care is critical in the management of fibromyalgia.

- Reduce stress. Develop a plan to avoid or limit overexertion and emotional stress. Allow yourself time each day to relax. That may mean learning how to say no without guilt. But try not to change your routine completely. People who quit work or drop all activity tend to do worse than do those who remain active. Try stress management techniques, such as deep-breathing exercises or meditation.

- Get enough sleep. Because fatigue is one of the main characteristics of fibromyalgia, getting sufficient sleep is essential. In addition to allotting enough time for sleep, practice good sleep habits, such as going to bed and getting up at the same time each day and limiting daytime napping.

- Exercise regularly. At first, exercise may increase your pain. But doing it gradually and regularly often decreases symptoms. Appropriate exercises may include walking, swimming, biking and water aerobics. A physical therapist can help you develop a home exercise program. Stretching, good posture and relaxation exercises also are helpful.

- Pace yourself. Keep your activity on an even level. If you do too much on your good days, you may have more bad days. Moderation means not overdoing it on your good days, but likewise it means not self-limiting or doing too little on the days when symptoms flare.

- Maintain a healthy lifestyle. Eat healthy foods. Limit your caffeine intake. Do something that you find enjoyable and fulfilling every day.

Alternative medicine

Complementary and alternative therapies for pain and stress management aren’t new. Some, such as meditation and yoga, have been practiced for thousands of years. But their use has become more popular in recent years, especially with people who have chronic illnesses, such as fibromyalgia.

Several of these treatments do appear to safely relieve stress and reduce pain, and some are gaining acceptance in mainstream medicine. But many practices remain unproved because they haven’t been adequately studied.

- Acupuncture. Acupuncture is a Chinese medical system based on restoring normal balance of life forces by inserting very fine needles through the skin to various depths. According to Western theories of acupuncture, the needles cause changes in blood flow and levels of neurotransmitters in the brain and spinal cord. Some studies indicate that acupuncture helps relieve fibromyalgia symptoms, while others show no benefit.

- Massage therapy. This is one of the oldest methods of health care still in practice. It involves use of different manipulative techniques to move your body’s muscles and soft tissues. Massage can reduce your heart rate, relax your muscles, improve range of motion in your joints and increase production of your body’s natural painkillers. It often helps relieve stress and anxiety.

- Yoga and tai chi. These practices combine meditation, slow movements, deep breathing and relaxation. Both have been found to be helpful in controlling fibromyalgia symptoms.

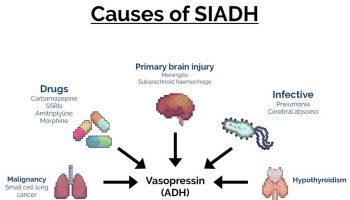

Chronic pain syndrome causes

The cause of chronic pain syndrome is multifactorial and complex and still is poorly understood. Some authors have suggested that chronic pain syndrome might be a learned behavioral syndrome that begins with a noxious stimulus that causes pain. This pain behavior then is rewarded externally or internally. Thus, this pain behavior is reinforced, and then it occurs without any noxious stimulus. Internal reinforcers are relief from personal factors associated with many emotions (eg, guilt, fear of work, sex, responsibilities). External reinforcers include such factors as attention from family members and friends, socialization with the physician, medications, compensation, and time off from work.

Patients with several psychological syndromes (eg, major depression, somatization disorder, hypochondriasis, conversion disorder) are prone to developing chronic pain syndrome.

Various neuromuscular, reproductive, gastrointestinal (GI), and urologic disorders may cause or contribute to chronic pain. Sometimes multiple contributing factors may be present in a single patient.

In a study by Alonso-Blanco 29, a connection was found in women between the number of active myofascial trigger points (MTrPs) and the intensity of spontaneous pain, as well as widespread mechanical hypersensitivity. Nociceptive inputs from these MTrPs may be linked to central sensitization.

A literature review by Gupta et al 30 indicated that in chronic pain patients, primary sensorimotor structural and functional changes are more prominent in females than in males. Males and females differed with regard to the nature and degree of insula changes (with males showing greater insula reactivity), as well as in the extent of anterior cingulate structural changes and in reactivity to emotional arousal.

Chronic pain syndrome symptoms

Chronic pain syndrome is pain that lasts more than several months (variously defined as 3 to 6 months, but longer than “normal healing”) 1, 2. Common chronic pain syndrome include headache, low back pain, cancer pain, arthritis pain, neurogenic pain (pain resulting from damage to the peripheral nerves or to the central nervous system itself), psychogenic pain (pain not due to past disease or injury or any visible sign of damage inside or outside the nervous system). A person may have two or more co-existing chronic pain conditions, several of which cause pain, may occur together. Such conditions can include chronic fatigue syndrome, endometriosis, fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease, interstitial cystitis (painful bladder syndrome), temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and vulvodynia (chronic vulvar pain).

Chronic pain syndrome complications

Chronic pain syndrome can affect patients in various ways. Major effects in the patient’s life are depressed mood, poor-quality or nonrestorative sleep, fatigue, reduced activity and libido, excessive use of drugs and alcohol, dependent behavior, and disability out of proportion with impairment 31.

Chronic pain may lead to prolonged physical suffering, marital or family problems, loss of employment, and various adverse medical reactions from long-term therapy.

Parental chronic pain increases the risk of internalizing symptoms, including anxiety and depression, in adolescents 32.

A study by van Tilburg et al 33 indicates that adolescents who have chronic pain and depressive thoughts are at increased risk for suicide ideation and attempt.

Chronic pain syndrome diagnosis

The decision to perform any laboratory or imaging evaluations is based on the need to confirm the diagnosis and to rule out other potentially life-threatening illnesses. Sometimes certain investigations are needed to provide appropriate and safe medical or surgical treatment. The recommended treatment should be based on clinical findings or changes in examination findings.

Extreme care should be taken during diagnostic testing for chronic pain syndrome. Carefully review prior testing to eliminate unnecessary repetition.

Routine complete blood count (CBC), urinalysis, and selected tests for suspected disease are important. Urine or blood toxicology is important for drug detoxification, as well as opioid therapy.

Imaging studies

Imaging studies, including with radiography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and computed tomography (CT) scanning, are important tools in the workup of patients with chronic pain syndrome.

Chronic pain syndrome treatment

Management of chronic pain in patients with multiple problems is complex, usually requiring specific treatment, simultaneous psychological treatment, and physical therapy 34. Physical therapy techniques include hot or cold applications, positioning, stretching exercises, traction, massage, ultrasonographic therapy, transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS), and manipulations.

Other treatments include nerve blocks, spinal cord stimulation, and intrathecal morphine pumps.

Treatment of chronic pain syndrome must be tailored for each individual patient. The treatment should be aimed at interruption of reinforcement of the pain behavior and modulation of the pain response. The goals of treatment must be realistic and should be focused on restoration of normal function (minimal disability), better quality of life, reduction of use of medication, and prevention of relapse of chronic symptoms.

Psychological interventions, in conjunction with medical intervention, physical therapy, and occupational therapy (OT), increase the effectiveness of the treatment program 35. Family members are involved in the evaluation and treatment processes.

Appropriate caution must be taken during chronic pain syndrome treatment in patients who exhibit any of the following behaviors:

- Poor response to prior appropriate management

- Unusual, unexpected response to prior specific treatment

- Avoidance of school, work, or other social responsibility

- Severe depression

- Severe anxiety disorder

- Excessive pain behavior

- Physician shopping

- Noncompliance with treatment in the past

- Drug abuse or dependence

- Family, marital, or sexual problems

- History of physical or sexual abuse

National health professional organizations have issued guidelines for treating several chronic pain syndrome 36.

Hospitalization usually is not required for patients with chronic pain syndrome, but it depends on how invasive the treatment choice is for pain control and on the severity of the case.

Patients with chronic pain syndrome generally are treated on an outpatient basis and require a variety of health care professionals to manage their condition optimally.

A clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians 37 encourages the use of non-pharmacologic approaches as initial treatment for chronic low-back pain. The options they suggest include several complementary approaches—acupuncture, mindfulness-based stress reduction, tai chi, yoga, progressive relaxation, biofeedback, and spinal manipulation—as well as conventional methods such as exercise and cognitive behavioral therapy.

The American College of Rheumatology 38 mentions several complementary approaches in its guidelines for the management of osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. For osteoarthritis of the knee, the guidelines mention tai chi as one of several nondrug approaches that might be helpful. The same guidelines, however, discourage using the dietary supplements glucosamine and chondroitin for osteoarthritis of the hip or knee.

The American College of Gastroenterology 39 included probiotics/prebiotics, peppermint oil, and hypnotherapy in its evaluation of approaches for managing irritable bowel syndrome. The American College of Gastroenterology found only weak evidence that any of these approaches may be helpful.

Complementary medicine

Some recent research has looked at the effects of complementary approaches on chronic pain syndrome in general rather than on specific painful conditions. A growing body of evidence suggests that some complementary approaches, such as acupuncture, hypnosis, massage, mindfulness meditation, spinal manipulation, tai chi, and yoga, may help to manage some painful conditions.

- A 2017 review 40 looked at complementary approaches with the opioid crisis in mind, to see which ones might be helpful for relieving chronic pain and reducing the need for opioid therapy to manage pain. There was evidence that acupuncture 41, yoga, relaxation techniques, tai chi, massage, and osteopathic or spinal manipulation 42 may have some benefit for chronic pain, but only for acupuncture was there evidence that the technique could reduce a patient’s need for opioids.

- Research shows that hypnosis is moderately effective in managing chronic pain, when compared to usual medical care. However, the effectiveness of hypnosis can vary from one person to another.

- A 2017 review of studies of mindfulness meditation for chronic pain showed that it is associated with a small improvement in pain symptoms.

- Studies have shown that music can reduce self-reported pain and depression symptoms in people with chronic pain 43.

Although the mind and body practices studied for chronic pain have good safety records, that doesn’t mean that they’re risk-free for everyone. Your health and special circumstances (such as pregnancy) may affect the safety of these approaches. If you’re considering natural products, remember that natural doesn’t always mean safe and that some natural products may have side effects or interact with medications.

Mind and body practices, such as acupuncture, hypnosis, massage therapy, mindfulness/meditation, relaxation techniques, spinal manipulation, tai chi/qi gong, and yoga, are generally safe for healthy people if they’re performed appropriately.

- People with medical conditions and pregnant women may need to modify or avoid some mind and body practices.

- Like other forms of exercise, mind and body practices that involve movement, such as tai chi and yoga, can cause sore muscles and may involve some risk of injury.

- It’s important for practitioners and teachers of mind and body practices to be properly qualified and to follow appropriate safety precautions.

Chronic pain syndrome prognosis

Many people with chronic pain can be helped if they understand all the causes of pain and the many and varied steps that can be taken to undo what chronic pain has done. Scientists believe that advances in neuroscience will lead to more and better treatments for chronic pain in the years to come.

- Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Finnerup NB, First MB, Giamberardino MA, Kaasa S, Korwisi B, Kosek E, Lavand’homme P, Nicholas M, Perrot S, Scholz J, Schug S, Smith BH, Svensson P, Vlaeyen JWS, Wang SJ. Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease: the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain. 2019 Jan;160(1):19-27. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, et al. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain. 2015;156(6):1003–1007. doi:10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4450869[↩][↩]

- Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of chronic pain. 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press, 1994. p. 1.[↩]

- Clifford JC. Successful management of chronic pain syndrome. Can Fam Physician. 1993 Mar;39:549-59. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2379763/pdf/canfamphys00109-0087.pdf[↩]

- Chronic Pain has arrived in the ICD-11 https://www.iasp-pain.org/PublicationsNews/NewsDetail.aspx?ItemNumber=8340[↩]

- Chronic Pain: In Depth. https://nccih.nih.gov/health/pain/chronic.htm[↩]

- Pain as a global public health priority. Goldberg DS, McGee SJ. BMC Public Health. 2011 Oct 6; 11():770.[↩]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee: An Update Review. Comparative Effectiveness Review no. 190. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017.[↩]

- Treede RD, Rief W, Barke A, Aziz Q, Bennett MI, Benoliel R, Cohen M, Evers S, Finnerup NB, First MB, Giamberardino MA, Kaasa S, Kosek E, Lavand’homme P, Nicholas M, Perrot S, Scholz J, Schug S, Smith BH, Svensson P, Vlaeyen JWS, Wang SJ. A classification of chronic pain for ICD-11. Pain. 2015 Jun;156(6):1003-1007. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000160 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4450869[↩]

- Gagnier JJ, Oltean H, van Tulder MW, Berman BM, Bombardier C, Robbins CB. Herbal Medicine for Low Back Pain: A Cochrane Review. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2016 Jan;41(2):116-33. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0000000000001310[↩]

- Cameron M, Chrubasik S. Oral herbal therapies for treating osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 May 22;2014(5):CD002947. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD002947.pub2[↩]

- Singh JA, Noorbaloochi S, Macdonald R, Maxwell LJ. Chondroitin for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2017(6). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005614.pub2[↩]

- Bennett MI, Kaasa S, Barke A, Korwisi B, Rief W, Treede RD. The IASP Taskforce for the classification of chronic pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: chronic cancer-related pain. PAIN 2019;160:38–44.[↩]

- Caraceni A, Portenoy RK; a working group of the IASP Task Force on Cancer Pain. An international survey of cancer pain characteristics and syndromes. IASP Task Force on Cancer Pain. International Association for the Study of Pain. Pain. 1999 Sep;82(3):263-274. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00073-1[↩]

- Chronic pain as a symptom or a disease the IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) PAIN: January 2019 – Volume 160 – Issue 1 – p 19–27 doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001384[↩]

- Caraceni A, Portenoy RK; Working Group of the IASP Task Force on Cancer Pain. An international survey of cancer pain characteristics and syndromes. PAIN 1999;82:263–74.[↩]

- Geber C, Breimhorst M, Burbach B, Egenolf C, Baier B, Fechir M, Koerber J, Treede RD, Vogt T, Birklein F. Pain in chemotherapy-induced neuropathy—more than neuropathic? PAIN 2013;154:2877–87.[↩]

- Macrae WA. Chronic post-surgical pain: 10 years on. Br J Anaesth 2008;101:77–86[↩]

- Haroutiunian S, Nikolajsen L, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS. The neuropathic component in persistent postsurgical pain: a systematic literature review. PAIN 2013;154:95–102.[↩]

- Jensen MP, Chodroff MJ, Dworkin RH. The impact of neuropathic pain on health-related quality of life: review and implications. Neurology 2007;68:1178–82.[↩]

- Jensen TS, Baron R, Haanpää M, Kalso E, Loeser JD, Rice AS, Treede RD. A new definition of neuropathic pain. PAIN 2011;152:2204–5[↩][↩]

- Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, Cruccu G, Dostrovsky JO, Griffin JW, Hansson P, Hughes R, Nurmikko T, Serra J. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology 2008;70:1630–5.[↩]

- Headache Classification Committee. The International Classification of Headache Disorders. Vol. 38. 3rd ed.: Cephalalgia, 2018. p. 1–211.[↩]

- Benoliel R, Birman N, Eliav E, Sharav Y. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: accurate diagnosis of orofacial pain? Cephalalgia 2008;7:752–62.[↩]

- Schiffman E, Ohrbach R, et al. Diagnostic Criteria for Temporomandibular Disorders (DC/TMD) for Clinical and Research Applications: Recommendations of the International RDC/TMD Consortium Network* and Orofacial Pain Special Interest Groupdagger. J Oral Facial Pain Headache 2014;28:6–27.[↩]

- Schwartz ES, Gebhart GF. Visceral Pain. Curr Top Behav Neurosci 2014;20:171–97.[↩]

- Giamberardino MA, Affaitati G, Costantini R. Referred pain from internal organs. In: Cervero F, Jensen TS, editors. , editors. Handbook of clinical neurology. Amsterdam: Elsevier, 2006. p. 343–61.[↩]

- Cervero F. Visceral pain—central sensitization. Gut 2000;47:56–7.[↩]

- Alonso-Blanco C, Fernández-de-Las-Peñas C, Morales-Cabezas M, Zarco-Moreno P, Ge HY, Florez-García M. Multiple active myofascial trigger points reproduce the overall spontaneous pain pattern in women with fibromyalgia and are related to widespread mechanical hypersensitivity. Clin J Pain. 2011 Jun. 27(5):405-13.[↩]

- Gupta A, Mayer EA, Fling C, et al. Sex-based differences in brain alterations across chronic pain conditions. J Neurosci Res. 2017 Jan 2. 95 (1-2):604-616.[↩]

- Kashikar-Zuck S, Cunningham N, Sil S, et al. Long-term outcomes of adolescents with juvenile-onset fibromyalgia in early adulthood. Pediatrics. 2014 Mar. 133(3):e592-600.[↩]

- Kroenke K, Bair MJ, Damush TM, et al. Optimized antidepressant therapy and pain self-management in primary care patients with depression and musculoskeletal pain: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009 May 27. 301(20):2099-110.[↩]

- van Tilburg MA, Spence NJ, Whitehead WE, Bangdiwala S, Goldston DB. Chronic pain in adolescents is associated with suicidal thoughts and behaviors. J Pain. 2011 Oct. 12(10):1032-9.[↩]

- Durosaro O, Davis MD, Hooten WM, et al. Intervention for erythromelalgia, a chronic pain syndrome: comprehensive pain rehabilitation center, Mayo Clinic. Arch Dermatol. 2008 Dec. 144(12):1578-83.[↩]

- Tang NK, Salkovskis PM, Hodges A, et al. Chronic pain syndrome associated with health anxiety: a qualitative thematic comparison between pain patients with high and low health anxiety. Br J Clin Psychol. 2009 Mar. 48:1-20.[↩]

- Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Treatment of Osteoarthritis of the Knee: An Update Review. Comparative Effectiveness Review no. 190. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2017. [↩]

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2017;166(7):514-530.[↩]

- Hochberg MC, Altman RD, April KT, et al. American College of Rheumatology 2012 recommendations for the use of nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapies in osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Care & Research. 2012;64(4):465-474.[↩]

- Ford AC, Moayyedi P, Chey WD, et al. American College of Gastroenterology monograph on management of irritable bowel syndrome. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2018;113(Suppl 2):1-18.[↩]

- Lin Y-C, Wan L, Jamison RN. Using integrative medicine in pain management: an evaluation of current evidence. Anesthesia and Analgesia. 2017;125(6):2081-2093.[↩]

- Vickers AJ, Vertosick EA, Lewith G, et al. Acupuncture for chronic pain: update of an individual patient data meta-analysis. Journal of Pain. 2018;19(5):455-474.[↩]

- Nahin RL, Boineau R, Khalsa PS, Stussman BJ, Weber WJ. Evidence-based evaluation of complementary health approaches for pain management in the United States. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2016;91(9):1291-1306.[↩]

- Garza-Villareal E, Pando V, Vuust P, et al. Music-induced analgesia in chronic pain conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Pain Physician. 2017;20(7):597-610.[↩]