Congestive Heart failure

Congestive Heart Failure (CHF) also known as heart failure is a heart condition that develops when your heart muscle has become too weak to pump blood and oxygen effectively through your body to support the muscles and organs in your body. Heart failure can also happen if your heart becomes too stiff to fill up with blood properly, so not enough blood and oxygen is pumped around your body. As a result, your muscles and organs don’t get enough oxygen and nutrients. This may cause fluid to build up in your body, legs and make you feel breathless or tired. The term “heart failure” does not mean that your heart has stopped. However, heart failure is a serious condition that needs medical care.

Other names for Heart Failure

- Congestive heart failure.

- Left-side heart failure. This is when the heart can’t pump enough oxygen-rich blood to the body.

- Right-side heart failure. This is when the heart can’t fill with enough blood.

- Cor pulmonale. This term refers to right-side heart failure caused by high blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries and right ventricle (lower right heart chamber).

In 2024, more than 6.7 million adults 20 years old or older in the United States have heart failure, according to the American Heart Association 1.

Heart failure can develop suddenly (the acute kind) or over time as your heart gets weaker (the chronic kind). Heart failure is usually an ongoing (chronic) condition — unlike heart attacks, which occur suddenly and require immediate treatment (acute). However, both conditions can be related: a heart attack can cause ongoing muscle weakness and stiffness making your heart not able to fill up with enough blood that leads to long-term heart failure. In some cases, symptoms of heart failure can also start suddenly.

Heart failure can affect one or both sides of your heart. Left-sided and right-sided heart failure may have different causes. Most often, heart failure is caused by another medical condition that damages your heart. This includes coronary heart disease, heart inflammation, high blood pressure, cardiomyopathy, or an irregular heartbeat. Heart failure may not cause symptoms right away. But eventually, you may feel tired and short of breath and notice fluid buildup in your lower body, around your stomach, or your neck.

Your body depends on the heart’s pumping action to deliver oxygen- and nutrient-rich blood to the body’s cells. When the cells are nourished properly, the body can function normally. Heart failure, sometimes known as congestive heart failure, occurs when your heart muscle doesn’t pump blood as well as it should and the heart can’t pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs 2. With heart failure, the weakened heart can’t supply the cells with enough blood. This results in fatigue and shortness of breath and some people have coughing. Everyday activities such as walking, climbing stairs or carrying groceries can become very difficult. This inability may also result in fluid retention, which causes swelling, for example, in the legs, feet, or abdomen.

The term “heart failure” makes it sound like the heart is no longer working at all and there’s nothing that can be done, but that is not the case at all. Heart failure also doesn’t mean that your heart has stopped or is about to stop working.

Congestive heart failure is a type of heart failure which requires seeking timely medical attention, although sometimes heart failure and congestive heart failure, the two terms are used interchangeably.

As blood flow out of the heart slows, blood returning to the heart through the veins backs up, causing congestion in the body’s tissues. Often swelling (edema) results. Most often there’s swelling in the legs and ankles, but it can happen in other parts of the body, too.

Sometimes fluid collects in the lungs and interferes with breathing, causing shortness of breath, especially when a person is lying down. This is called pulmonary edema and if left untreated can cause respiratory distress.

Heart failure also affects the kidneys’ ability to dispose of sodium and water. This retained water also increases swelling in the body’s tissues (edema).

Congestive heart failure is a serious medical condition in which the heart cannot pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs. As blood flow out of the heart slows, blood returning to the heart through the veins backs up, causing congestion in the body’s tissues. Often swelling (edema) results. Most often there’s swelling in the legs and ankles, but it can happen in other parts of the body, too 3.

Sometimes fluid collects in the lungs and interferes with breathing, causing shortness of breath, especially when a person is lying down. This is called pulmonary edema and if left untreated can cause respiratory distress 3.

Heart failure also affects the kidneys’ ability to dispose of sodium and water. This retained water also increases swelling in the body’s tissues (edema) 3.

Congestive heart failure is often caused by hypertension, diabetes, or coronary heart disease, gradually leave your heart too weak or stiff to fill and pump efficiently.

It is estimated that 6.7 million adults in the United States have congestive heart failure 2 and at least 10 million in Europe 4. Congestive heart failure is one of the most common reasons those aged 65 and over are hospitalized 5.

- There were 1 million hospitalizations for congestive heart failure in 2000 and in 2010.

- About half of people who develop heart failure die within 5 years of diagnosis 6.

- Most congestive heart failure hospitalizations were for those aged 65 and over, but the proportion under age 65 increased significantly from 23% in 2000 to 29% in 2010.

- The overall rate of congestive heart failure hospitalization per 10,000 population did not change significantly from 2000 to 2010 (35.5 compared with 32.8), but the trends were different for those under and over age 65.

- From 2000 to 2010, the rate of congestive heart failure hospitalization for males under age 65 increased significantly while the rate for females aged 65 and over decreased significantly.

- In both 2000 and in 2010, a greater share of inpatients under age 65, compared with those aged 65 and over, were discharged to their homes.

Heart failure can damage your liver or kidneys. Other conditions it can lead to include pulmonary hypertension or other heart conditions, such as an irregular heartbeat, heart valve disease, and sudden cardiac arrest. One way to prevent heart failure is to control conditions that cause heart failure, such as coronary artery disease, high blood pressure, diabetes or obesity.

Some common symptoms of heart failure include:

- Chest pain (angina).

- Dizziness.

- Fatigue.

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea).

- Swollen hands or feet (edema).

Your doctor will diagnose heart failure based on your medical and family history, a physical exam, and results from imaging and blood tests.

Currently, heart failure is a serious condition and not all conditions that lead to heart failure can be reversed, but treatments can improve the signs and symptoms of heart failure and help you live longer. Lifestyle changes — such as exercising, reducing salt in your diet, managing stress and losing weight — can improve your quality of life.

Heart failure therapies treat the underlying cause of low ejection fraction. In some cases of heart failure, the heart can’t fill with enough blood. In other cases, the heart can’t pump blood to the rest of the body with enough force. Some people have both problems. For heart failure due to an arrhythmia, you may benefit from a biventricular pacemaker. People with heart failure due to other causes, like high blood pressure, may need medications.

Heart failure treatments include:

- Biventricular pacemaker.

- Heart failure medications.

- Heart transplant.

- Heart valve repair or replacement.

- Implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD).

You can take additional steps to relieve strain on your heart and get the most out of treatment. Many people with mild heart failure enhance their quality of life by doing these:

- Increasing physical activity. A cardiac rehabilitation program can help you safely get started. Talk to your doctor before starting a new exercise routine if you haven’t been physically active.

- Maintaining a healthy weight.

- Limiting the amount of sodium and volume of fluids you consume.

- Quitting unhealthy habits, such as smoking, recreational drugs and alcohol. Limit caffeine.

- Track your daily fluid intake. You may need a diuretic medication to help get rid of extra fluid in your body.

- Eat a heart-healthy diet. A dietitian or nutritionist can help you build a healthy, filling meal plan.

- Manage stress, either through yoga, meditation or other stress management techniques.

- Get plenty of sleep at night.

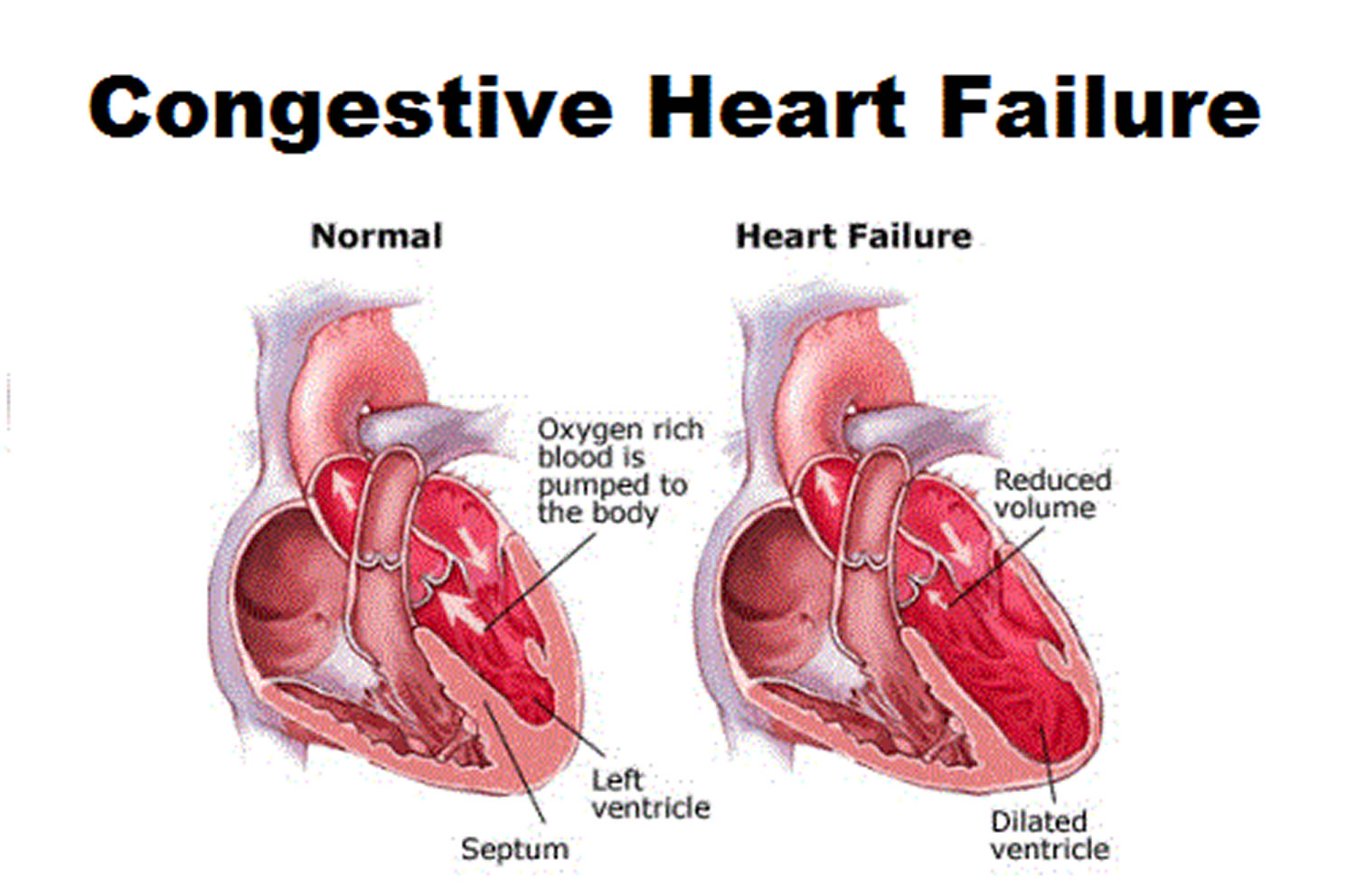

Figure 1. Congestive Heart Failure

Figure 2. Congestive heart failure signs and symptoms

[Source 7 ]See your doctor if you think you might have symptoms of heart failure. Call your local emergency services number and get emergency medical help if you have any of the following:

- Chest pain.

- Fainting or severe weakness.

- Rapid or irregular heartbeat with shortness of breath, chest pain or fainting.

- Sudden, severe shortness of breath and coughing up white or pink, foamy mucus.

These symptoms may be due to heart failure. But there are many other possible causes. Don’t try to diagnose yourself.

At the emergency room, doctors do tests to learn if your symptoms are due to heart failure or something else.

See your doctor right away if you have heart failure and:

- Your symptoms suddenly get worse.

- You develop a new symptom.

- You gain 5 pounds (2.3 kilograms) or more within a few days.

Such changes could mean that existing heart failure is getting worse or that treatment isn’t working.

How your Heart Works

Your heart is a muscular organ that pumps blood to your body. Your heart is at the center of your circulatory system. The circulatory system consists of a network of blood vessels, such as arteries, veins, and capillaries. These blood vessels carry blood to and from all areas of your body.

An electrical system controls your heart and uses electrical signals to contract the heart’s walls. When the heart walls contract, blood is pumped into your circulatory system. Inlet and outlet valves in your heart chambers ensure that blood flows in the right direction.

Your heart is vital to your health and nearly everything that goes on in your body. Without your heart’s pumping action, blood can’t move throughout your body.

Your blood carries the oxygen and nutrients that your organs need to work well. Blood also carries carbon dioxide (a waste product) to your lungs so you can breathe it out.

A healthy heart supplies your body with the right amount of blood and oxygen at the rate needed to work well. If disease or injury weakens your heart, your body’s organs won’t receive enough blood to work normally.

Your heart has 2 sides, separated by an inner wall called the septum. The right side of the heart pumps blood to your lungs to pick up oxygen. The left side of your heart receives the oxygen-rich blood from the lungs and pumps it to the body.

Figure 3. The anatomy of human heart

Figure 4. The anatomy of the heart chambers

Figure 5. Normal heart blood flow

Figure 6. The heart’s electrical system

Heart Chambers

Your heart has 4 chambers 8, 2 on the right and 2 on the left:

- 2 upper chambers are called atrium (two is called an atria). The atria collect blood as it flows into your heart.

- 2 lower chambers are called ventricles.

- Right ventricle (RV) pumps Deoxygenated blood out of your heart to your lungs. Deoxygenated blood, also known as venous blood, is blood that has a lower oxygen concentration and a higher concentration of carbon dioxide than oxygenated blood.

- Left ventricle (LV) pumps Oxygenated blood out of your heart to other parts of your body. Oxygenated blood, also known as arterial blood, is blood rich in oxygen, typically bright red, that is pumped from the left ventricle of your heart to your body through arteries (aorta) after picking up oxygen in your lungs.

Your heart also has 4 valves that open and close to let blood flow from the atria to the ventricles and from the ventricles into the two large arteries connected to the heart in only one direction when the heart contracts (beats). The four heart valves are:

- Tricuspid valve, located between the right atrium and right ventricle

- Pulmonary or pulmonic valve, between the right ventricle and the pulmonary artery. The pulmonary artery carries blood from your heart to your lungs.

- Mitral valve, between the left atrium and left ventricle

- Aortic valve, between the left ventricle and the aorta. This aorta carries blood from the heart to the body.

Each valve has a set of flaps also called leaflets or cusps. The mitral valve has two flaps; the others have three. Valves are like doors that open and close. They open to allow blood to flow through to the next chamber or to one of the arteries. Then they shut to keep blood from flowing backward. Blood flow occurs only when there’s a difference in pressure across the valves, which causes them to open. Under normal conditions, the valves permit blood to flow in only one direction.

Your heart 4 chambers and 4 valves and is connected to various blood vessels. Veins are blood vessels that carry blood from the body to your heart. Arteries are blood vessels that carry blood away from your heart to your body.

Your heart pumps blood to your lungs and to all the body’s tissues by a sequence of highly organized contractions of the four chambers. For your heart to function properly, the four chambers must beat in an organized way.

When your heart’s valves open and close, they make a “lub-DUB” sound that a doctor can hear using a stethoscope 9.

- The First heart sound (S1) — the “lub” —is made by the mitral and tricuspid valves closing at the beginning of systole. Systole is when the ventricles contract, or squeeze, and pump blood out of the heart.

- The Second heart sound (S2) — the “DUB” —is made by the aortic and pulmonary valves closing at the beginning of diastole. Diastole is when the ventricles relax and fill with blood pumped into them by the atria.

Arteries

The arteries are major blood vessels connected to your heart.

- Pulmonary artery carries blood from the right side of the heart to the lungs to pick up a fresh supply of oxygen.

- Aorta is the main artery that carries oxygen-rich blood from the left side of the heart to the body.

- Coronary arteries are the other important arteries attached to the heart. They carry oxygen-rich blood from the aorta to the heart muscle, which must have its own blood supply to function.

Veins

The veins also are major blood vessels connected to your heart.

- Pulmonary veins carry oxygen-rich blood from the lungs to the left side of the heart so it can be pumped to the body.

- Superior vena cava (SVC) and inferior vena cava (IVC) are large veins that carry oxygen-poor blood (deoxygenated blood or venous blood) from the body back to the heart.

Blood Flow

The Right Side of Your Heart

In figure 5 above, the superior vena cava (SVC) and inferior vena cava (IVC) are shown in blue to the left of the heart muscle as you look at the picture. The superior vena cava (SVC) and inferior vena cava (IVC) are the largest veins in your body.

After your body’s organs and tissues have used the oxygen in your blood, the vena cavae carry the oxygen-poor blood (deoxygenated blood or venous blood) back to the right atrium of your heart.

- The superior vena cava (SVC) carries oxygen-poor blood from the upper parts of your body, including your head, chest, arms, and neck.

- The inferior vena cava (IVC) carries oxygen-poor blood from the lower parts of your body from the abdomen and lower extremities back to the right side of your heart for oxygenation.

The oxygen-poor blood (deoxygenated blood or venous blood) from the vena cavae flows into your heart’s right atrium. From the right atrium, blood is pumped into the right ventricle. And then from the right ventricle, blood is pumped to your lungs through the pulmonary arteries (shown in blue in the center of figure 5).

Once in the lungs, the blood travels through many small, thin blood vessels called capillaries. There, the blood picks up more oxygen and transfers carbon dioxide to the lungs—a process called gas exchange.

The oxygen-rich blood passes from your lungs back to your heart through the pulmonary veins (shown in red to the left of the right atrium in figure 5).

The Left Side of Your Heart

Oxygen-rich blood from your lungs passes through the pulmonary veins (shown in red to the right of the left atrium in figure 5 above). The blood enters the left atrium and is pumped into the left ventricle.

From the left ventricle, the oxygen-rich blood is pumped to the rest of your body through the aorta. The aorta is the main artery that carries oxygen-rich blood to your body.

Like all of your organs, your heart needs oxygen-rich blood. As blood is pumped out of your heart’s left ventricle, some of it flows into the coronary arteries (shown in red in figure 5).

Your coronary arteries are located on your heart’s surface at the beginning of the aorta. They carry oxygen-rich blood to all parts of your heart.

For the heart to work well, your blood must flow in only one direction. Your heart’s valves make this possible. Both of your heart’s ventricles have an “in” (inlet) valve from the atria and an “out” (outlet) valve leading to your arteries.

Healthy valves open and close in exact coordination with the pumping action of your heart’s atria and ventricles. Each valve has a set of flaps called leaflets or cusps that seal or open the valve. This allows blood to pass through the chambers and into your arteries without backing up or flowing backward.

Heart’s Electrical System

To understand arrhythmias, it helps to understand the heart’s internal electrical system. The heart’s electrical system controls the rate and rhythm of the heartbeat.

With each heartbeat, an electrical signal spreads from the top of the heart to the bottom. As the signal travels, it causes the heart to contract and pump blood.

Your heart’s electrical system controls all the events that occur when your heart pumps blood 10. The electrical system also is called the cardiac conduction system. If you’ve ever seen the heart test called an EKG (electrocardiogram), you’ve seen a graphical picture of the heart’s electrical activity.

Your heart’s electrical system is made up of three main parts:

- Sinoatrial (SA) node, located in the right atrium of your heart

- Atrioventricular (AV) node, located on the interatrial septum close to the tricuspid valve

- His-Purkinje system, located along the walls of your heart’s ventricles

A heartbeat is a complex series of events. These events take place inside and around your heart. A heartbeat is a single cycle in which your heart’s chambers relax and contract to pump blood. This cycle includes the opening and closing of the inlet and outlet valves of the right and left ventricles of your heart.

Each heartbeat has two basic parts: diastole and systole. During diastole, the atria and ventricles of your heart relax and begin to fill with blood.

At the end of diastole, your heart’s atria contract (atrial systole) and pump blood into the ventricles. The atria then begin to relax. Your heart’s ventricles then contract (ventricular systole), pumping blood out of your heart.

Each electrical signal begins in a group of cells called the sinus node or sinoatrial (SA) node. The SA node is located in the heart’s upper right chamber, the right atrium. In a healthy adult heart at rest, the SA node fires off an electrical signal to begin a new heartbeat 60 to 100 times a minute. In a normal, healthy heart, each beat begins with a signal from the SA node. This is why the SA node sometimes is called your heart’s natural pacemaker. Your pulse, or heart rate, is the number of signals the SA node produces per minute.

The signal is generated as the vena cavae fill your heart’s right atrium with blood from other parts of your body. The signal spreads across the cells of your heart’s right and left atria.

From the SA node, the electrical signal travels through special pathways in the right and left atria. This causes the atria to contract and pump blood through the open valves from the atria into heart’s two lower chambers, the ventricles.

The electrical signal then moves down to a group of cells called the atrioventricular (AV) node, located between the atria and the ventricles. Here, the signal slows down just a little, allowing your heart’s right and left ventricles time to finish filling with blood.

The electrical signal then leaves the AV node and travels along a pathway called the bundle of His. This pathway divides into a right bundle branch and a left bundle branch. The signal goes down these branches to the ventricles, causing them to contract and pump blood to the lungs and the rest of the body.

From the bundle of His, the signal fibers divide into left and right bundle branches through the Purkinje fibers. These fibers connect directly to the cells in the walls of your heart’s left and right ventricles.

The signal spreads across the cells of your ventricle walls, and both ventricles contract. However, this doesn’t happen at exactly the same moment.

The left ventricle contracts an instant before the right ventricle. This pushes blood through the pulmonary valve (for the right ventricle) to your lungs, and through the aortic valve (for the left ventricle) to the rest of your body.

As the signal passes, the walls of the ventricles relax and await the next signal.

This process continues over and over as the atria refill with blood and more electrical signals come from the SA node.

A problem with any part of this process can cause an arrhythmia. For example, in atrial fibrillation, a common type of arrhythmia, electrical signals travel through the atria in a fast and disorganized way. This causes the atria to quiver instead of contract.

What is ejection fraction?

Ejection fraction (EF) is a measurement of your heart’s ability to pump oxygen-rich blood out to your body, expressed as a percentage (%), of how much oxygen-rich blood the left ventricle (LV) pumps out with each heart contraction 11. Ejection fraction (EF) refers to how well your heart pumps blood. Ejection fraction (EF) is the amount of blood pumped out of your heart’s lower chambers (ventricles) each time it contracts. An ejection fraction (EF) of 60 percent means that 60 percent of the total amount of blood in the left ventricle (LV) is pushed out with each heartbeat. A normal heart’s ejection fraction (normal EF) is between 50 and 70 percent 11. With each heartbeat, 50% to 70% of the blood in your left ventricle gets pumped out to your body. However, it is important to note that you can have a normal ejection fraction measurement and still have heart failure. This is called heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) previously known as diastolic heart failure. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) happens when your heart’s muscle has become so thick and stiff that the ventricle holds a smaller than usual volume of blood. In this case, your heart might still have an ejection fraction that falls in the normal range (EF≥50%) because your heart is pumping out a normal percentage of the blood that enters it. But in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), the total amount of blood pumped isn’t enough to meet your body’s needs.

To understand ejection fraction (EF), it’s helpful to understand how blood flows through your heart:

- Blood enters your heart through the top right section (right atrium).

- Between heartbeats, there’s a short pause (diastole, the phase of the heartbeat when your heart muscle relaxes and allows heart chambers to fill with blood). This is when blood flows through a valve down to the left ventricle.

- Once the ventricle is full, the next heartbeat pumps out (ejects) a portion of the blood out to the body. Also called systole, the phase of the heartbeat when your heart muscle contracts and pumps blood from the heart chambers into the arteries.

Table 1. Ejection Fraction Percentage

| Sex | Normal | Mildly Abnormal | Moderately Abnormal | Severely Abnormal |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 52% to 72% | 41% to 51% | 30% to 40% | Below 30% |

| Female | 54% to 74% | 41% to 53% | 30% to 40% | Below 30% |

Types of ejection fraction

There are 2 types of ejection fraction: left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF). Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) measures how much blood gets pumped from the left ventricle with each contraction. Typically, ejection fraction refers to left ventricular. Right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) measures how much blood is pumped out of the right side of the heart, to the lungs.

Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF)

Ejection fraction (EF) typically refers to the left side of your heart or left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF). It shows how much oxygen-rich blood is pumped out of the left ventricle (LV) to most of your body’s organs with each contraction. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) helps determine the severity of dysfunction on the left side of your heart.

Right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF)

Right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) measures the amount of oxygen-poor blood or deoxygenated blood or venous blood pumped out of the right side of your heart to your lungs for oxygen. Right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) is important if you have right-sided heart failure. But this condition is not as common as left-sided heart failure.

What’s an unhealthy ejection fraction?

Ejection fraction (EF) refers to how well your heart pumps blood. The ejection fraction is the percentage of blood pumped out of the ventricle after a heart contraction. Ejection fraction (EF) is the amount of blood pumped out of your heart’s lower chambers (ventricles) each time it contracts. Your ejection fraction is an indicator of how well your heart is working. A low ejection fraction typically means you have or are at risk for heart failure. An ejection fraction (EF) from 41 to 49 percent (EF from 41% to 49%) might be considered too low. The lower your heart’s ejection fraction, the weaker your heart’s pumping action is. This occurs in people with severe heart failure. You can also have a low ejection fraction in the earlier stages of heart failure. However, ejection fraction (EF) does not always indicate that a person is developing heart failure, but it could indicate damage, perhaps from a previous heart attack. Some people with a normal ejection fraction also have heart failure. This is known as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). An ejection fraction measurement under 40 percent (EF<40%) might be evidence of heart failure or cardiomyopathy (disease of the heart muscle that makes it harder for the heart to pump blood). In severe cases, ejection fraction (EF) can be even lower than 40.

According to the American Heart Association:

- Ejection fraction 50 to 70% (EF = 50% to 70%): Normal heart function.

- Ejection fraction 41 to 49% (EF = 41% to 49%): A mildly reduced left ventricle (LV) ejection fraction. Can indicate previous heart damage from heart attack or cardiomyopathy. You might not experience heart failure symptoms. Or, you may have symptoms with physical activity but not at rest.

- Ejection fraction less than 40% (EF < 40%): Your heart pumping ability is below normal. The lower the ejection fraction, the higher the risk of life-threatening complications, like cardiac arrest. Symptoms may be severe and may affect you even when sitting still.

- Ejection fraction greater than 75% (EF > 75%): Can indicate a heart condition like hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), a genetic heart condition where the heart muscle thickens, making it harder for the heart to pump blood effectively. This thickening can lead to various symptoms and complications, including shortness of breath, chest pain, and an increased risk of arrhythmias and a common cause of sudden cardiac arrest.

The lower your ejection fraction, the more severe your heart failure symptoms may be. You might experience:

- Confusion.

- Fatigue.

- Heart palpitations.

- Nausea.

- Shortness of breath (dyspnea).

- Water retention in your abdomen or feet.

- Weakness.

Some things that may cause a reduced ejection fraction are:

- Weakness of the heart muscle, such as cardiomyopathy.

- Heart attack that damaged the heart muscle.

- Heart valve disease.

- Long-term, uncontrolled high blood pressure.

What is the formula for ejection fraction?

The ejection fraction (EF) formula equals the amount of blood pumped out of the ventricle with each contraction (stroke volume or SV) divided by the end-diastolic volume (EDV), the total amount of blood in the ventricle. To express as a percentage, you would multiply by 100.

- Ejection fraction (EF) = (stroke volume [SV]/end-diastolic volume [EDV]) x 100

Stroke volume (SV) is the volume of blood pumped out of the heart’s left ventricle during each systolic cardiac contraction. Ventricular stroke volume (SV) is often thought of as the amount of blood (mL) ejected per beat by the left ventricle into the aorta (or from the right ventricle into the pulmonary artery). Moreover, a more precise definition for stroke volume (SV) and one that is used in echocardiography when assessing ventricular function is the difference between the ventricular end-diastolic volume (EDV) and the end-systolic volume (ESV). The end-diastolic volume (EDV) is the filled volume of the ventricle before contraction, and the end-systolic volume (ESV) is the residual volume of blood remaining in the ventricle after ejection. In a typical heart, the end-diastolic volume (EDV) is about 120 mL of blood and the end-systolic volume (ESV) is about 50 mL of blood 13. The difference in the end-diastolic volume (EDV) and the end-systolic volume (ESV), 70 mL, that is Stroke volume (SV) = end-diastolic volume (EDV) – end-systolic volume (ESV). Therefore, any factor that alters either the EDV or the ESV will change the SV. For example, an increase in EDV increases SV, whereas an increase in ESV decreases SV.

Who should have their ejection fraction measured?

It’s helpful to know your ejection fraction if you have or are at risk for a condition that can lead to heart failure.

This includes:

- ATTR amyloidosis (transthyretin amyloidosis), which can affect the heart. ATTR amyloidosis or transthyretin amyloidosis, is a rare, progressive disease where misfolded transthyretin (TTR) protein deposits as amyloid in organs and tissues, primarily affecting the heart and nerves, and can lead to heart failure

- Cancer or other conditions requiring chemotherapy, which sometimes causes heart damage (cardiotoxicity).

- Congenital heart disease. Congenital heart disease refers to heart problems present at birth, caused by abnormal development of the heart or blood vessels during fetal development. It’s the most common type of birth defect, affecting about 1 in 100 live-born babies.

- Heart attack. A heart attack also known as a myocardial infarction, occurs when a coronary artery, which supplies blood to your heart, becomes blocked, usually by a blood clot, depriving your heart muscle of oxygen, potentially causing damage or death. It’s a medical emergency requiring immediate treatment

- Heart valve disease.

- Myocarditis. Myocarditis is inflammation of the heart muscle (myocardium) that can weaken your heart and its ability to pump blood effectively, potentially leading to irregular heart rhythms or heart failure.

- Severe high blood pressure. Severe high blood pressure also called malignant hypertension or hypertensive crisis (blood pressure 180/120 mmHg or higher), is a medical emergency requiring immediate attention, potentially leading to heart attack, stroke, or other life-threatening complications

- Ventricular arrhythmia. Ventricular arrhythmias are abnormal heart rhythms originating in the heart’s lower chambers (ventricles), potentially causing a fast, irregular heartbeat and potentially life-threatening conditions like ventricular fibrillation.

What are the tests used to measure ejection fraction?

There are several reasons why your doctor might want to test your ejection fraction. For example, if you have symptoms like fatigue or shortness of breath, your doctor may want to see if your heart is failing. Your doctor also may want to test your ejection fraction if you have a history of heart disease, high blood pressure or diabetes. Testing your ejection fraction can help your doctor figure out if you have heart failure and how severe it is. It also can help guide treatment decisions.

Your doctor may order these tests to determine your ejection fraction:

- Echocardiography (echocardiogram) also known as an “echo”, is a non-invasive ultrasound test that uses sound waves to create images of your heart, allowing doctors to assess its structure and function. Echocardiography (echocardiogram) is the most common test used to measure ejection fraction.

- Cardiac catheterization: Cardiac catheterization is a medical procedure that involves inserting a thin, flexible tube (catheter) into a blood vessel, typically in the groin or arm, and guiding it to the heart to diagnose and/or treat heart conditions.

- Heart MRI scan, also called a cardiac MRI. This test uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of the heart.

- Multigated acquisition scan (MUGA), also called a nuclear stress test or radionuclide ventriculography (RNVG) or equilibrium radionuclide angiocardiography (ERNA). A multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan is an imaging test to evaluate how your heart pumps blood. A MUGA scan measures your ejection fraction (EF). A multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan uses an injection of a substance called a radionuclide and a specialized camera. As the radionuclide travels through your blood, your doctor takes pictures of your heart. A multigated acquisition (MUGA) scan measures how your heart muscle contracts and relaxes while you rest or exercise.

- Cardiac computed tomography (CT) scan. A cardiac computed tomography (CT) scan is a procedure that utilizes multiple X-ray beams from different angles to acquire high-quality, three-dimensional (3D) images of your heart, along with your great vessels and surrounding structures. This quick but detailed and high-resolution scan shows your doctor problems with your heart structure, valves, arteries, aorta and more.

Is ejection fraction the only test for heart failure?

Ejection fraction is one of many parameters your heart doctor use to assess heart failure. Additional testing makes it possible to pinpoint the cause so that you receive appropriate therapies.

Additional tests your heart doctor use to diagnose heart disease include:

- Angiography or angiogram. An angiogram is a diagnostic procedure that uses X-ray images to look for blockages or narrow spots in your blood vessels (arteries or veins). An injected contrast material makes it easy to see where blood is moving and where blockages are. Your doctor can use X-rays or other types of imaging for your angiogram. Doctor use an angiogram of your heart, neck, kidneys, legs or other areas to locate the source of an artery or vein issue. Your doctor may want to do an angiogram procedure when you have signs of blocked, damaged or abnormal blood vessels.

- Chest X-ray. A chest X-ray is a test that creates an image of your heart, lungs and bones. Doctors use chest X-rays to diagnose or treat conditions like heart disease, pneumonia, emphysema or COPD.

- Echocardiogram.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG). Electrocardiogram (ECG/EKG) is a quick, noninvasive test diagnostic tool that records your heart’s electrical activity. Doctors use ECG for many reasons, like to diagnose heart rhythm issues or to monitor how well a treatment is working.

- Exercise stress test. An exercise stress test helps determine how well your heart responds during times when it’s working its hardest. It typically involves walking on a treadmill or pedaling on a stationary bike while hooked up to an EKG (ECG) to monitor your heart’s activity. If you can’t exercise, you receive medications that make your heart pump harder and faster or dilate the artery supplying blood to your heart (coronary arteries).

How often should my ejection fraction be measured?

Your heart doctor may be concerned about your ejection fraction if you:

- Have symptoms of heart failure.

- Experience a heart attack or other condition that affects your heart function.

- Are living with a condition that raises your risk of heart failure.

The frequency of testing after a heart failure diagnosis depends on a variety of factors, including how low your initial ejection fraction reading was. If your ejection fraction continues worsening, you’ll need it checked more frequently. If it is stable, you might not need it checked as often.

How will I know if my ejection fraction is improving?

If you have a low ejection fraction, you’ll have frequent appointments with your heart specialist to monitor it. It’s essential to go to all your appointments, even if you don’t feel sick.

If your symptoms are fading, it may be a sign that ejection fraction is improving. But it’s also possible for symptoms to worsen or for new ones to appear. These issues may indicate a worsening ejection fraction.

Contact your heart specialist immediately — do not wait until your next appointment — if you experience:

- Difficulty breathing, especially when lying down.

- A heartbeat that feels unusually fast.

- Loss of appetite or vomiting.

- Sudden weight change, which could be a sign of fluid retention.

- Unexplained weakness or dizziness.

Who is at Risk for Congestive Heart failure?

About 6.7 million adults 20 years old or older in the United States have heart failure 14. The number of people who have heart failure is growing.

Heart failure is more common in:

- People who are age 65 or older. Aging can weaken the heart muscle. Older people also may have had diseases for many years that led to heart failure. Heart failure is a leading cause of hospital stays among people on Medicare. Heart failure is rare in people younger than 50. Studies have shown that around 2% of the population younger than 54 years old have heart failure. The number increases to around 8% — about 1 in 12 — for people over 75.

- Blacks are more likely to have heart failure than people of other races. They’re also more likely to have symptoms at a younger age, have more hospital visits due to heart failure, and die from heart failure.

- People who are overweight. Excess weight puts strain on the heart. Being overweight also increases your risk of heart disease and type 2 diabetes. These diseases can lead to heart failure.

- People who have had a heart attack. Damage to the heart muscle from a heart attack and can weaken the heart muscle.

Children who have congenital heart defects also can develop heart failure. These defects occur if the heart, heart valves, or blood vessels near the heart don’t form correctly while a baby is in the womb. Congenital heart defects can make the heart work harder. This weakens the heart muscle, which can lead to heart failure. Children don’t have the same symptoms of heart failure or get the same treatments as adults.

Types of Congestive Heart failure

Heart failure can involve the heart’s left side, right side or both sides. However, it usually affects the left side first.

Right-sided heart failure

The right heart’s pumping action moves “used” deoxygenated blood or venous blood that returns to the heart through the veins through the right atrium into the right ventricle. The right ventricle then pumps the blood back out of the heart into the lungs to be replenished with oxygen.

Right-sided heart failure also called right ventricular heart failure or right heart failure means your heart’s right ventricle is too weak to pump enough blood to the lungs. As a result:

- Blood builds up in your veins, vessels that carry blood from your body back to your heart.

- This buildup increases pressure in your veins.

- The pressure pushes fluid out of your veins and into other tissue.

- Fluid builds up in your legs, abdomen or other areas of your body, causing swelling.

Right-sided heart failure usually occurs as a result of left-sided failure. When the left ventricle fails, increased fluid pressure is, in effect, transferred back through the lungs, ultimately damaging the heart’s right side. When the right side loses pumping power, blood backs up in the body’s veins. This usually causes swelling or congestion in the legs, ankles and swelling within the abdomen such as the gastrointestinal tract and liver causing ascites (accumulation of fluid in the peritoneal cavity, causing abdominal swelling).

Right-sided heart failure treatment focuses on managing symptoms so the disease doesn’t worsen. Healthy lifestyle habits, along with cardiac rehab, improve symptoms for many people. Other treatment options include cardiac devices and surgery. If you have shortness of breath, swelling or chest discomfort, talk to your doctor.

Right-sided heart failure prevention

You may not always be able to prevent heart failure. But you can sometimes treat conditions that cause heart failure.

If you treat these conditions early, you may be able to stop heart failure before it starts:

- Abnormal heart rhythms.

- Alcohol use disorder.

- Anemia.

- Coronary artery blockage.

- Heart valve disorders.

- High blood pressure.

- Obesity.

- Obstructive sleep apnea.

- Thyroid disorders.

Right-sided heart failure causes

Most right-sided heart failure occurs because of left-sided heart failure. The entire heart gradually weakens.

Left-sided heart failure results from another heart condition, such as:

Sometimes, right-sided heart failure can be caused by:

- High blood pressure in the lungs (pulmonary hypertension). Pulmonary hypertension specifically refers to high blood pressure in the pulmonary arteries, the blood vessels that carry blood from your heart to your lungs. Pulmonary hypertension is characterized by abnormally high blood pressure in the arteries of the lungs, which can lead to heart failure and requires specialist treatment. Pulmonary hypertension can be caused by various conditions, including lung diseases (like COPD or pulmonary fibrosis), heart problems, blood clots in the lungs (pulmonary embolism), or even certain medications. One type, pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH), involves narrowing or blockage of the blood vessels in the lungs. Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) can be idiopathic (cause unknown), heritable (genetic), or associated with other medical conditions. Autoimmune diseases, birth defects of the heart, and chronic low oxygen levels in the blood can also contribute to pulmonary hypertension.

- Pulmonary embolism (PE). A pulmonary embolism (PE) is a life-threatening condition that occurs when a blood clot blocks an artery in your lung. It can cause permanent lung damage and death. Blood clots most commonly come from the deep veins of your legs, a condition known as deep vein thrombosis. In many cases, multiple clots are involved.

- Lung diseases such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is an umbrella term for a group of lung diseases that cause airflow obstruction and difficulty breathing, often caused by prolonged exposure to irritants like cigarette smoke.

Right-sided heart failure symptoms

The main sign of right-sided heart failure is fluid buildup. This buildup leads to swelling (edema) in your:

- Feet, ankles and legs.

- Lower back.

- Gastrointestinal tract and liver (causing ascites).

Other signs include:

- Breathlessness.

- Chest pain and discomfort.

- Heart palpitations.

Where you accumulate fluid depends on how much extra fluid and your position. If you’re standing, fluid typically builds up in your legs and feet. If you’re lying down, it may build up in your lower back. And if you have a lot of excess fluid, it may even build up in your belly.

Fluid build up in your liver or stomach may cause:

- Nausea.

- Bloating.

- Appetite loss.

Once right-sided heart failure becomes advanced, you can also lose weight and muscle mass. Doctors call these effects cardiac cachexia (a form of malnutrition and muscle wasting that can occur in people with advanced heart failure, leading to unintentional weight loss, fatigue, and reduced quality of life, often associated with a poor prognosis).

Right-sided heart failure diagnosis

To diagnose heart failure, your doctor will:

- Ask you about your symptoms. Often, this can be enough for your doctor to suspect heart failure.

- Perform a physical exam. Your doctor will take your pulse and blood pressure, listen to your heart and lungs and look for signs of swelling.

Your doctor will test your heart function using:

- Chest X-ray.

- Electrocardiogram (EKG).

- Echocardiogram.

- Blood tests, especially to measure substances called natriuretic peptides (NPs).

To confirm a diagnosis of heart failure or rule out other conditions causing your symptoms, you may need:

- Heart MRI.

- Heart CT.

- Cardiac catheterization.

- Stress test.

- Nuclear exercise stress test.

Right-sided heart failure treatment

Right-sided heart failure treatment is directed at the underlying cause of your heart failure, and not all causes of right-sided heart failure are curable. But you can treat heart failure and improve your symptoms. Often, a combination of lifestyle changes, medications and heart devices can help you manage heart failure and live an active life.

Cardiac rehabilitation, or rehab, is a program supervised by health professionals. It can help slow the progression of heart failure. Cardiac rehab usually includes:

- Exercise training, including an activity program tailored to fit your health goals.

- Education on heart-healthy living, nutrition, medication and how to manage your condition.

- Counseling to help reduce stress.

Medications treat right heart failure

Your heart doctor will determine the right medication or combination of medications that will help you feel your best. These may include:

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, angiotensin 2 receptor blockers (ARBs) and angiotensin-receptor neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs) to lower blood pressure.

- Channel blocker and beta blockers to reduce heart rate.

- Aldosterone antagonists and diuretics to get rid of excess fluid.

Your heart doctor may also prescribe:

- Anticoagulants (blood thinners).

- Cholesterol-lowering drugs.

- Digoxin is sometimes used to treat arrhythmia (irregular heartbeat).

For severe heart failure, your heart doctor may recommend:

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD).

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), a type of pacemaker.

- Left ventricular assist device (LVAD).

If nonsurgical methods aren’t working, your heart doctor may talk to you about surgery for heart failure. There’s no procedure specifically for heart failure. But sometimes heart doctors identify a problem that surgery can correct. For example, surgery can repair a problem with your heart valve or coronary artery.

Heart failure surgery options may include:

- Percutaneous coronary intervention.

- Coronary artery bypass.

- Valve replacement.

- Heart transplant.

Right-sided heart failure prognosis

For many people, the right combination of medications and lifestyle changes can slow or stop the heart failure and improve symptoms. They can lead full, active lives. About 1 in 10 American adults who live with heart failure have advanced heart failure. That means treatments aren’t working, and symptoms are getting worse. You may feel symptoms, such as shortness of breath, even when you’re sitting. If you have advanced heart failure, talk with your heart specialist about palliative care and important care decisions. Palliative care focuses on improving the quality of life for individuals with serious illnesses and their families by addressing physical, psychological, social, and spiritual needs, and can be provided alongside curative treatments or as a primary focus.

Left-sided heart failure

The left side of your heart pumps fresh oxygen-rich blood from your lungs to the left atrium, then on to the left ventricle, which pumps it to the rest of your body. The left ventricle supplies most of your heart’s pumping power because it has to pump blood through your whole body, so the left ventricle is larger and stronger than the right ventricle. In left-sided heart failure or left ventricular heart failure, the left side of the heart must work harder to pump the same amount of blood. When people have left-sided heart failure, their heart’s left side has to work harder to pump the same amount of blood. Left-sided heart failure is the most common cause of right-sided heart failure.

When the left ventricle stops working efficiently:

- The left ventricle pumps less blood out to the body.

- The reduced blood flow causes blood to back up behind the left ventricle, into the left atrium, lungs and eventually the right ventricle.

- The backup causes higher blood pressure, which damages the right side of the heart. The damaged right side stops pumping efficiently, and blood builds up in the veins.

- As pressure increases in the veins, it pushes fluid into surrounding tissues.

- The fluid buildup causes swelling and congestion throughout your body.

There are 2 types of left-sided heart failure 15. Drug treatments are different for the two types:

- Heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF), also called systolic failure: The left ventricle loses its ability to contract normally. The heart can’t pump with enough force to push enough blood into circulation. When this occurs, the heart is pumping less than or equal to 40% EF (ejection fraction).

- Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), also called diastolic failure or diastolic dysfunction: The left ventricle loses its ability to relax normally because the muscle has become stiff. The heart can’t properly fill with blood during the resting period between each beat. When this occurs, the heart is pumping greater than or equal to 50%.

- Heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction (HFmrEF) is a newer concept. In this type of heart failure, the left ventricle pumps between 41% and 49% EF (ejection fraction). This places people with HFmrEF between the heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) groups.

Left-sided heart failure causes

Left-sided heart failure may occur in people with:

- Coronary artery disease.

- Heart attack.

- High blood pressure.

- Valvular heart disease.

- Abnormal heart rhythms.

- Infiltrative diseases such as amyloidosis and sarcoidosis.

Other risk factors for left-sided heart failure include:

- Certain chemotherapy treatments for cancer that cause cardiotoxicity (heart toxicity).

- Diabetes.

- Obesity.

- Sleep apnea.

- Older age.

- Smoking.

- Toxins to your heart such as certain drugs and energy drinks.

- Less commonly, certain medications that are used to treat different disease processes, like autoimmune diseases and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Left-sided heart failure prevention

Living a heart-healthy lifestyle can lower your risk of left-sided heart failure. If you’ve already have left-sided heart failure, healthy habits can help you avoid future issues.

Steps you can take to prevent left-sided heart failure include:

- Manage your blood pressure or coronary artery disease.

- Regular physical activity and a good night’s sleep.

- Maintain a healthy weight and eat fruits and vegetables.

- Manage stress with deep breathing or relaxation techniques.

- Quitting tobacco if you use it and avoiding secondhand smoke.

Left-sided heart failure symptoms

Left-sided heart failure symptoms may be mild at first or you may think it’s a cold or allergy. You might not even notice them. But as your heart function worsens, you may experience:

- Constant coughing.

- Shortness of breath with walking or bending over.

- Waking up short of breath or unable to lie flat at night.

- Weight gain.

- Swelling (edema) in your ankles, legs or abdomen.

Over time, your heart works harder to do its job. This causes complications that may include:

- Cardiogenic shock. Cardiogenic shock is a life-threatening condition where the heart’s pumping function is severely impaired to meet the body’s needs, leading to organ damage and potentially death if not treated immediately

- Enlarged heart. An enlarged heart, also known as cardiomegaly, is a condition where the heart becomes larger than normal, often as a result of underlying conditions that make the heart work harder, such as high blood pressure or heart valve disease.

- Abnormal heart rates and rhythms (arrhythmia).

Left-sided heart failure complications

Complications of left-sided heart failure depend on your age, overall health and the severity of your heart disease. They may include:

- Kidney damage or failure. Heart failure can reduce the blood flow to the kidneys. Untreated, this can cause kidney failure. Kidney damage from heart failure can require dialysis for treatment.

- Other heart changes. Heart failure can cause changes in the heart’s size and function. These changes may damage heart valves and cause irregular heartbeats.

- Liver damage. Heart failure can cause fluid buildup that puts too much pressure on the liver. This fluid backup can lead to scarring, which makes it more difficult for the liver to work properly.

- Sudden cardiac death. If your heart is weak, there is a risk of dying suddenly due to a dangerous irregular heart rhythm.

- Arrhythmias or abnormal heart rhythms such as ventricular tachycardia and atrial fibrillation (Afib).

- Obstructive and central sleep apnea.

- Heart valve disease (leaky valves).

- Right-sided heart failure.

- Frailty and muscle weakness.

- Anemia.

- Depression or anxiety.

Left-sided heart failure diagnosis

To diagnose heart failure, your doctor examines you and asks questions about your symptoms and medical history. Your doctor checks to see if you have risk factors for heart failure, such as high blood pressure, coronary artery disease or diabetes.

Your doctor will listen to your lungs and heart with a device called a stethoscope. A whooshing sound called a murmur may be heard when listening to your heart. Your doctor may look at the veins in your neck and check for swelling in your legs and belly.

Tests that may be done to diagnose heart failure may include:

- Blood tests. Blood tests can help diagnose diseases that can affect the heart. Blood tests also can look for a specific protein made by the heart and blood vessels. In heart failure, the level of this protein goes up.

- Chest X-ray. X-ray images can show the condition of the lungs and heart.

- Electrocardiogram (ECG or EKG). This quick and painless test records the electrical signals in the heart. It can show how fast or how slowly the heart is beating.

- Echocardiogram. Sound waves create images of the beating heart. This test shows the size and structure of the heart and heart valves and blood flow through the heart.

- Ejection fraction. Ejection fraction is a measurement of the percentage of blood leaving your heart each time it squeezes. This measurement is taken during an echocardiogram. The result helps classify heart failure and guides treatment. An ejection fraction of 50% or higher is considered ideal. But you can still have heart failure even if the number is considered ideal.

- Exercise tests or stress tests. These tests often involve walking on a treadmill or riding a stationary bike while the heart is monitored. Exercise tests can show how the heart responds to physical activity. If you can’t exercise, you might be given medicines.

- CT scan of the heart also called cardiac CT scan, this test uses X-rays to create cross-sectional images of the heart.

- Heart MRI scan, also called a cardiac MRI. This test uses magnetic fields and radio waves to create detailed images of the heart.

- Coronary angiogram. This test helps spot blockages in the heart arteries. The healthcare professional inserts a long, thin flexible tube called a catheter into a blood vessel, usually in the groin or wrist. It’s then guided to the heart. Dye flows through the catheter to arteries in the heart. The dye helps the arteries show up more clearly on X-ray images and video.

- Myocardial biopsy. In this test, a heart doctor removes very small pieces of the heart muscle for examination. This test may be done to diagnose certain types of heart muscle diseases that cause heart failure.

Left-sided heart failure treatment

Treatment of heart failure depend on the cause. Treatment often includes lifestyle changes and medicines. If another health condition is causing your heart to fail, treating it may reverse your heart failure. Some people with heart failure need surgery to open blocked arteries or to place a device to help the heart work better. With treatment, symptoms of heart failure may improve.

Medications

A combination of medicines may be used to treat heart failure. The specific medicines used depend on the cause of your heart failure and the symptoms. Medicines to treat heart failure include:

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. These medicines relax blood vessels to lower blood pressure, improve blood flow and decrease the strain on the heart. Examples include enalapril (Vasotec, Epaned), lisinopril (Zestril, Qbrelis) and captopril.

- Angiotensin 2 receptor blockers (ARBs). These medicines have many of the same benefits as ACE inhibitors. They may be an option for people who can’t tolerate ACE inhibitors. They include losartan (Cozaar), valsartan (Diovan) and candesartan (Atacand).

- Angiotensin receptor plus neprilysin inhibitors (ARNIs). This medicine uses two blood pressure medicines to treat heart failure. The combination medicine is sacubitril-valsartan (Entresto). It’s used to treat some people with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. It may help prevent the need for a hospital stay in those people.

- Beta blockers. These medicines slow the heart rate and lower blood pressure. They reduce the symptoms of heart failure and help the heart work better. If you have heart failure, beta blockers may help you live longer. Examples include carvedilol (Coreg), metoprolol (Lopressor, Toprol-XL, Kapspargo Sprinkle) and bisoprolol.

- Diuretics or water pills, these medicines make you urinate more frequently. This helps prevent fluid buildup in your body. Diuretics, such as furosemide (Lasix, Furoscix), also decrease fluid in the lungs, so it’s easier to breathe. Some diuretics make the body lose potassium and magnesium. Your doctor may recommend supplements to treat this. If you’re taking a diuretic, you may have regular blood tests to check your potassium and magnesium levels.

- Potassium-sparing diuretics also called aldosterone antagonists, these medicines include spironolactone (Aldactone, CaroSpir) and eplerenone (Inspra). They may help people with severe heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF) live longer. Unlike some other diuretics, these medicines can raise the level of potassium in the blood to dangerous levels. Talk with your doctor about your diet and potassium intake.

- Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors. These medicines help lower blood sugar. They are often prescribed with diet and exercise to treat type 2 diabetes. But they’re also one of the first treatments for heart failure. That’s because several studies showed that sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors lowered the risk of hospital stays and death in people with certain types of heart failure — even if they didn’t have diabetes. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT2) inhibitors medicines include canagliflozin (Invokana), dapagliflozin (Farxiga), and empagliflozin (Jardiance).

- Digoxin (Lanoxin) also called digitalis, helps the heart squeeze better to pump blood. It also tends to slow the heartbeat. Digoxin reduces heart failure symptoms in people with HFrEF. It may be more likely to be given to someone with a heart rhythm disorder, such as atrial fibrillation.

- Hydralazine and isosorbide dinitrate (BiDil). This combination of medicines helps relax blood vessels. It may be added to your treatment plan if you have severe heart failure symptoms and ACE inhibitors or beta blockers haven’t helped.

- Vericiguat (Verquvo). This medicine for chronic heart failure is taken once a day by mouth. It’s a type of medicine called an oral soluble guanylate cyclase stimulator. In studies, people with high-risk heart failure who took this medicine had fewer hospital stays for heart failure and heart disease-related deaths compared with those who got a dummy pill.

- Positive inotropes. These medicines may be given by IV to people with certain types of severe heart failure who are in the hospital. Positive inotropes can help the heart pump blood better and maintain blood pressure. Long-term use of these medicines has been linked to an increased risk of death in some people. Talk with your doctor about the benefits and risks of these medicines.

- Other medicines. Your doctor may prescribe other medicines to treat specific symptoms. For example, some people may receive nitrates for chest pain, statins to lower cholesterol or blood thinners to help prevent blood clots.

Your doctor may need to change your medicine doses frequently. This is more common when you’ve just started a new medicine or when your condition is getting worse.

You may need to stay in the hospital if you have a flare-up of heart failure symptoms. While in the hospital, you may receive:

- Medicines to relieve your symptoms.

- More medicines to help your heart pump better.

- Oxygen through a mask or small tubes placed in your nose.

If you have severe heart failure, you may need to use supplemental oxygen for a long time.

Surgery and other procedures

Surgery or other treatment to place a heart device may be recommended to treat the condition that led to heart failure.

Surgery or other procedures for heart failure may include:

- Coronary artery bypass graft surgery (CABG). You may need this surgery if severely blocked arteries are causing your heart failure. The surgery involves taking a healthy blood vessel from the leg, arm or chest and connecting it below and above the blocked arteries in the heart. The new pathway improves blood flow to the heart muscle.

- Heart valve repair or replacement. If a damaged heart valve causes heart failure, your care professional may recommend repairing or replacing the valve. There are many different types of heart valve surgery. The type needed depends on the cause of the heart valve disease. Heart valve repair or replacement may be done as open-heart or minimally invasive surgery.

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD). An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is used to prevent complications of heart failure. It isn’t a treatment for heart failure itself. An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is a device similar to a pacemaker. It’s implanted under the skin in the chest with wires leading through the veins and into the heart. The implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) checks the heartbeat. If the heart starts beating at a dangerous rhythm, the implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) tries to correct the beat. If the heart stops, the device shocks it back into regular rhythm. An ICD can also work as a pacemaker and speed up a slow heartbeat.

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) also called biventricular pacing, cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) is a treatment for heart failure in people whose lower heart chambers aren’t pumping in sync with each other. A device sends electrical signals to the lower heart chambers. The signals tell the chambers to squeeze in a more coordinated way. This improves the pumping of blood out of the heart. Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) may be used with an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD).

- Ventricular assist device (VAD). A ventricular assist device (VAD) helps pump blood from the lower chambers of the heart to the rest of the body. It’s also called a mechanical circulatory support device. Although a ventricular assist device (VAD) can be placed in one or both lower chambers of the heart, it’s usually placed in the lower left one. Your doctor may recommend a ventricular assist device (VAD) if you’re waiting for a heart transplant. Sometimes, a ventricular assist device (VAD) is used as a permanent treatment for people who have heart failure but who aren’t good candidates for a heart transplant.

- Heart transplant. Some people have such severe heart failure that surgery or medicines don’t help. These people may need to have their hearts replaced with a healthy donor heart. A heart transplant isn’t the right treatment for everyone. A team of doctors at a transplant center helps determine whether the procedure may be safe and beneficial for you.

Left-sided heart failure prognosis

Your outlook can be excellent as long you keep routine appointments with your heart doctor and take medications as recommended by your heart doctor.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) previously known as diastolic heart failure is a type of heart failure where the left ventricle (the heart’s main pumping chamber) has difficulty relaxing and filling with blood during the resting period between beats, even though it can pump blood effectively during contraction 16, 17, 18, 19, 20. In heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), your heart might still have an ejection fraction (EF) that falls in the normal range (ejection fraction≥50%) because your heart is pumping out a normal percentage of the blood that enters it 21. But in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), the total amount of blood pumped isn’t enough to meet your body’s needs 21.

Historically, heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) was termed diastolic heart failure; however, recent investigations suggest a more complex and heterogeneous pathophysiology 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28. Ventricular diastolic and systolic reserve abnormalities, chronotropic incompetence, stiffening of ventricular tissue, atrial dysfunction, pulmonary hypertension, impaired vasodilation, and endothelial dysfunction are all implicated 29, 30. Frequently, these abnormalities are noted only when the circulatory system is stressed.

Nearly half of all patients with heart failure have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) 31. The prevalence of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) or diastolic heart failure, continues to increase in the developed world, likely because of the increasing prevalence of common risk factors, including older age, female sex, high blood pressure (hypertension), metabolic syndrome, kidney disease and obesity.

High blood pressure (hypertension) in particular is a strong risk factor for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) or diastolic heart failure. 80 to 90 percent of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) or diastolic heart failure are hypertensive.

The diagnosis of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) can be challenging, particularly in patients with overt signs or symptoms of congestion 32. Hemodynamic exercise testing has emerged as the gold standard to definitively establish or refute the diagnosis heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) 24, 26, 33, but estimates from community-based studies still show that many patients with shortness of breath (dyspnea) due to heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) remain undiagnosed 34.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction causes

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) occurs in nearly 50% of all heart failure cases, and prevalence is growing due to longer life, hypertension, diabetes, obesity, coronary artery disease, hyperlipidemia and other cardiac conditions.

You may be at risk for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) if you have:

- Cardiac tamponade. Cardiac tamponade is a life-threatening condition where excessive fluid buildup in the pericardial sac (the sac that surrounds your heart). This fluid buildup increases pressure around your heart, preventing it from filling and emptying properly and impairing its ability to pump blood effectively, leading to a decrease in cardiac output and potentially causing shock requiring immediate medical attention.

- Cardiac tamponade can be caused by various factors, including:

- Trauma: Injuries to the chest that damage the heart or surrounding tissues.

- Infections: Pericarditis (inflammation of the pericardium) or other infections that cause fluid buildup.

- Medical conditions: Certain conditions, like uremia (kidney failure) or autoimmune diseases, can lead to pericardial effusion.

- Cancer: Malignant tumors that spread to the pericardium.

- Post-cardiac surgery: Complications from heart surgery can lead to fluid accumulation

- Cardiac tamponade can be caused by various factors, including:

- Coronary artery disease. Coronary artery disease also known as coronary heart disease, occurs when the coronary arteries that supply blood to your heart become narrowed or blocked, often due to plaque buildup, restricting blood flow and potentially leading to heart attack or other complications.

- Causes and risk factors for coronary artery disease or coronary heart disease include:

- Atherosclerosis: Atherosclerosis is the buildup of fats, cholesterol and other substances in and on the artery walls. This buildup is called plaque. The plaque can cause arteries to narrow, blocking blood flow. The plaque also can burst, leading to a blood clot. The most common cause of coronary artery disease (coronary heart disease) is atherosclerosis.

- High cholesterol (especially LDL or “bad” cholesterol)

- High blood pressure

- Smoking

- Diabetes

- Obesity

- Lack of physical activity

- Family history of heart disease

- Age (risk increases with age)

- Causes and risk factors for coronary artery disease or coronary heart disease include:

- Heart valve disease.

- High blood pressure (hypertension).

Cardiovascular and noncardiovascular conditions that may induce the acute decompensation of patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) include but are not limited to 35:

- Acute kidney injury or worsening chronic kidney disease

- Anemia

- Chronic pulmonary disease, or the exacerbation thereof

- Dysrhythmia, particularly tachyarrhythmia, especially new-onset atrial fibrillation

- Infection

- Ischemia

- Increased salt intake or water retention

- Medication noncompliance, including antihypertensive or diuretics

- Poorly controlled or uncontrolled hypertension.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction pathophysiology

At a cellular level, heart muscle cells (cardiac myocytes) in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) are thicker and shorter than normal heart muscle cells (myocytes), and collagen content is increased. Recent histologic studies have shown reductions in myocardial capillary density that may contribute. At the organ level, affected individuals may have concentric remodeling with or without hypertrophy, although many people have normal ventricular geometry. Increases in heart muscle cells (myocytes) stiffness are mediated in part by relative hypophosphorylation of the sarcomeric molecule titin, due to cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) deficiency thought to arise primarily as a consequence of increased nitroso-oxidative stress induced by comorbid conditions such as obesity, metabolic syndrome and aging. Cellular and tissue characteristics may become more pronounced as the disease progresses.

Most studies suggest that the rate of left ventricular (LV) pressure decay during isovolumic relaxation is prolonged, increasing left ventricle (LV) and left atrial (LA) pressure, especially with elevated heart rates, as during exercise.

Normal ventricular filling is achieved in large part by ventricular suction, the early active component of diastole, which is generated by:

- Intraventricular pressure gradients

- Mitral annular longitudinal motion

- Early diastolic left ventricle (LV) “untwisting”

- Elastic recoil induced by contraction to a smaller end systolic volume in the preceding contraction cycle.

Each of these four elements is impaired in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), especially with stress, so filling becomes dependent on high left atrial (LA) pressure to actively push blood into the left ventricle (LV), as opposed to the action of a normal left ventricle (LV), which “pulls” blood in during early diastole. Passive left ventricle (LV) end-diastolic stiffness (Eed) is quantified by the slope and position of the diastolic pressure-volume relationship. Left ventricle (LV) end-diastolic stiffness (Eed) increases with normal aging, but this increase is exaggerated in individuals with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) in most, but not all studies.

Although systolic function is relatively preserved, individuals with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) typically exhibit subtle abnormalities in systolic performance, which become more dramatic during exercise. Limited stroke volume reserve and chronotropic incompetence markedly limit cardiac output in response to exercise. Mechanical dyssynchrony is common even though electrical dyssynchrony is not. Atrial fibrillation is extremely common in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) (seen at some point in two-thirds of patients) and poorly tolerated because of the importance of LA contractile function in maintaining adequate LV chamber filling.

Pulmonary hypertension is common in patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF). Increased left atrial (LA) pressure adds in series with increased resistive and pulsatile pulmonary arterial loading to increase right ventricle (RV) afterload. This then leads to right ventricle (RV) dysfunction, which seems to be tightly correlated with the development of atrial fibrillation. With right ventricle (RV) failure, progressive systemic congestion occurs, manifested by malabsorption, congestive hepatopathy, cardiorenal syndrome, systemic inflammation and cardiac cachexia (a form of malnutrition and muscle wasting that can occur in people with advanced heart failure, leading to unintentional weight loss, fatigue, and reduced quality of life, often associated with a poor prognosis).

Increased right ventricle (RV) and left atrial (LA) size and subsequent increases in total cardiac volume can lead to pericardial restraint, preventing additional preload recruitment during exercise or saline loading and contributing to elevation in filling pressures and cardiac output plateau.

Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction symptoms

Patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) typically exhibit intolerance to physical activity characterized by exertional dyspnea (98%) and fatigue (59%) 36, 37. With the progression of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), these symptoms will occur with lower activity levels and may be accompanied by evidence of congestion 36, 37. Some patients with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) are clinically asymptomatic, or their symptoms are so mild they go unnoticed.

The remaining clinical manifestations of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) are typically the same as seen in other heart failure subtypes, including heart failure with reduced ejection fraction (HFrEF). Obtaining a thorough medical history and performing a comprehensive physical examination facilitate the classification of heart failure, which helps guide therapeutic interventions. The signs and symptoms of heart failure overlap with many other disease processes. Worsening ventricular dysfunction results in more severe symptoms and apparent signs. However, there is no single sign or symptom pathognomonic for heart failure.

It is reasonable to suspect heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) as a possible diagnosis in any patient with shortness of breath during physical activity (exertional dyspnea) and one of the following clinical parameters not otherwise explained by an alternative diagnosis 35:

- Age 60 or older

- Atrial fibrillation 38

- Chronic kidney disease

- Coronary artery disease

- Diabetes

- Hypertension

- Overweight/obesity 21