Devics disease

Devics disease also known as neuromyelitis optica (NMO) or neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder (NMOSD) is a rare autoimmune disorder that primarily affects the eye nerves (optic neuritis) and the spinal cord (myelitis). Devic’s disease or neuromyelitis optica can cause a wide range of symptoms, such as weakness or paralysis in the legs or arms, blindness, nerve pain, muscle spasms, loss of sensation, uncontrollable vomiting and hiccups, and bladder or bowel dysfunction from spinal cord damage. These will vary from person to person – some may only have one attack of symptoms and recover well, whereas others may be more severely affected and have a number of attacks that lead to disability. Children may experience confusion, seizures or coma with neuromyelitis optica. Devic’s disease can affect anyone at any age, but it’s more common in women than men. Neuromyelitis optica flare-ups may be reversible, but can be severe enough to cause permanent visual loss and problems with walking.

The cause of neuromyelitis optica is usually unknown, although it may sometimes appear after an infection, or it may be associated with another autoimmune condition. Devic’s disease or neuromyelitis optica is often misdiagnosed as multiple sclerosis (MS) or perceived as a type of MS, but NMO is a distinct condition.

Devic’s disease occurs in individuals of all races. The prevalence of Devic’s disease is approximately 1-10 per 100,000 individuals and seems to be similar worldwide, although somewhat higher rates have been reported in countries with a higher proportion of individuals of African ancestry 1. Relative to MS that it mimics, it occurs with greater frequency in individuals of Asian and African descent, but the majority of patients with this illness in Western countries are Caucasian. Individuals of any age may be affected, but typically Devic’s disease, especially cases seropositive for AQP4-IgG, occur in late middle-aged women. Equal numbers of men and women have the form that does not recur after the initial flurry of attacks, but women, especially those with aquaporin-4 autoantibody [AQP4-IgG], are four or five times more likely to be affected than men by the recurring (relapsing) form. Children represent may also be affected by this condition; children more commonly develop brain symptoms at onset and seem to have a higher frequency of monophasic presentation than adults.

At present, treatment of NMO is targeted at two facets of the disease:

- Control tissue inflammation and damage at onset or during relapse

- Prevent further tissue damage by reducing the frequency of relapse.

Devic’s disease key points

- Devic’s disease or neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders are inflammatory disorders of the central nervous system characterized by severe, immune-mediated demyelination and axonal damage predominantly targeting the optic nerves and spinal cord, but also the brain and brainstem. Devic’s disease can be distinguished from multiple sclerosis and other central nervous system inflammatory disorders by the presence of the disease-specific aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibody, which plays a direct role in the pathogenesis of Devic’s disease.

- The incidence of Devic’s disease in women is up to 10 times higher than in men. The median age of onset is 32 to 41 years, but cases are described in children and older adults.

- Hallmark features of Devic’s disease include acute attacks characterized by bilateral or rapidly sequential optic neuritis (leading to visual loss), acute transverse myelitis (often causing limb weakness and bladder dysfunction), and the area postrema syndrome (with intractable hiccups or nausea and vomiting). Other suggestive symptoms include episodes of excessive daytime somnolence or narcolepsy, reversible posterior leukoencephalopathy syndrome, neuroendocrine disorders, and (in children) seizures. While no clinical features are disease-specific, some are highly characteristic. Devic’s disease has a relapsing course in 90 percent or more of cases.

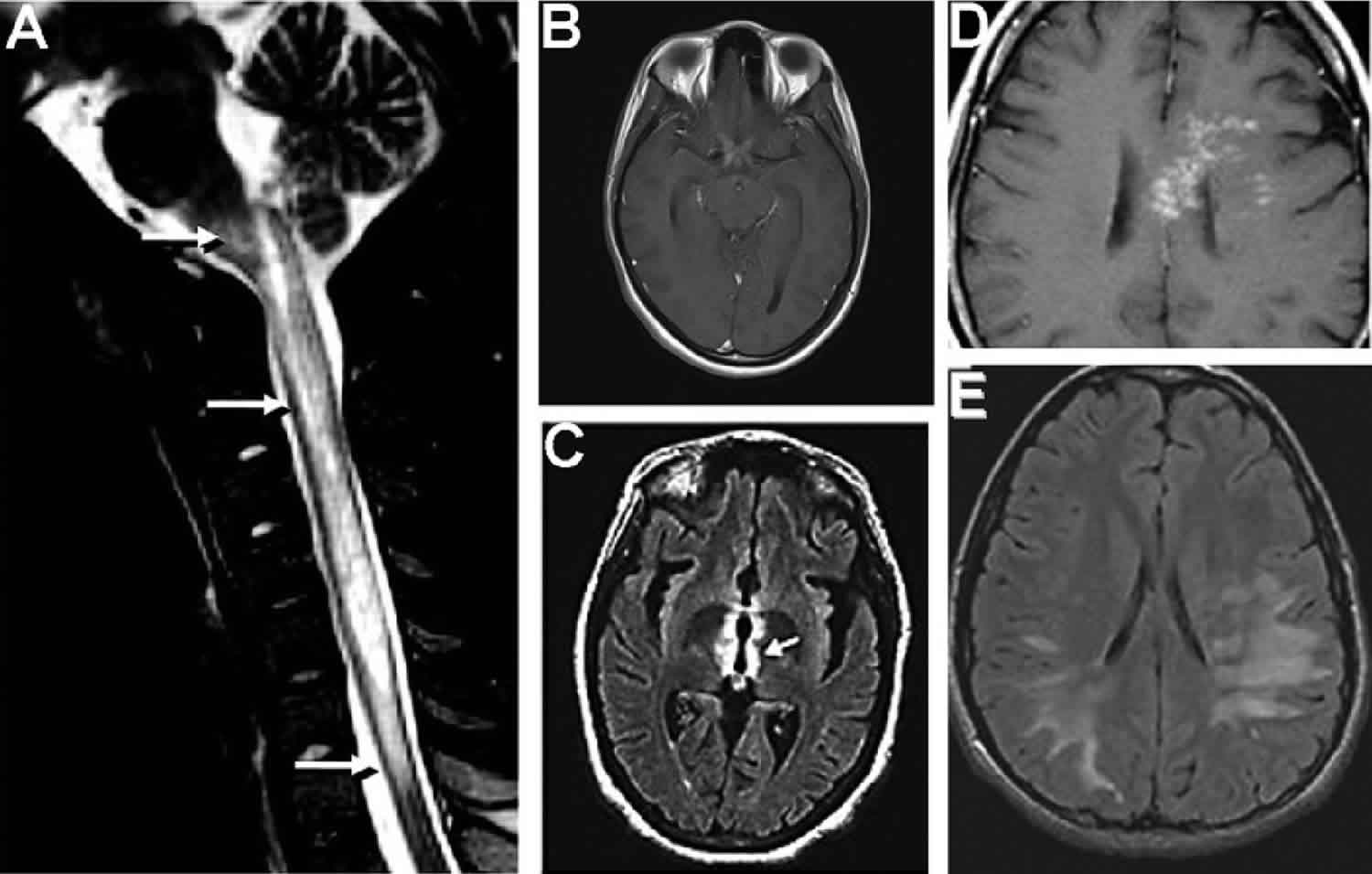

- In addition to a comprehensive history and examination, the evaluation of suspected Devic’s disease entails brain and spinal cord neuroimaging with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), determination of AQP4 antibody status, and often cerebrospinal fluid analysis. Diagnostic criteria for Devic’s disease require the presence of at least one core clinical characteristic (eg, optic neuritis, acute myelitis, area postrema syndrome), a positive test for AQP4-immunoglobulin G (IgG), and exclusion of alternative diagnoses. The diagnostic criteria are more exacting in the setting of negative or unknown AQP4-IgG antibody status.

- Devic’s disease must be distinguished from multiple sclerosis, which is the most common disorder likely to cause central nervous system demyelination. Other conditions that should be considered in the differential diagnosis include systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, neuro-Behçet disease, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis, and intrathecal spinal cord tumors. Devic’s disease may also be associated with anti-myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG) antibody seropositivity. However, the spectrum of disease associated with MOG autoantibodies is wider than with AQP4 autoantibodies.

- For patients with acute or recurrent attacks of Devic’s disease, we suggest initial treatment with high-dose intravenous methylprednisolone (1 gram daily for three to five consecutive days) (Grade 2C). For patients with severe symptoms, unresponsive to glucocorticoids, we suggest treatment with plasma exchange. Plasma exchange may be more effective if started early as adjunctive therapy with glucocorticoids.

- Because the natural history of Devic’s disease is one of stepwise deterioration due recurrent attacks and accumulated disability, long-term immunotherapy is indicated to reduce the risk of relapse as soon as the diagnosis of Devic’s disease is made. For patients with Devic’s disease who are seropositive for aquaporin-4 (AQP4) IgG antibodies, we suggest treatment with eculizumab rather than another immunosuppressive agent; eculizumab was highly effective for reducing the relapse rate compared with placebo in a randomized trial. For patients who meet diagnostic criteria for Devic’s disease without AQP4-IgG or who meet criteria with unknown AQP4-IgG status, alternative agents include rituximab, azathioprine, or mycophenolate.

- Immunosuppression is usually continued for at least five years for patients who are seropositive for AQP4-IgG, including those presenting with a single attack, because they are at high risk for relapse. However, the optimal drug regimen and treatment duration for Devic’s disease, with or without AQP4 seropositivity, are yet to be determined.

- The natural history of Devic’s disease is one of stepwise deterioration due to accumulating visual, motor, sensory, and bladder deficits from recurrent attacks. Long-term disability and mortality rates are high.

Is Devic’s disease a type of multiple sclerosis?

Until recently, Devic’s disease was thought to be a kind of multiple sclerosis (MS) that caused more severe problems with the optic nerves and spinal cord. Recent research has suggested that Devic’s disease is probably a different disease in which there is a specific immune attack on a molecule known as aquaporin 4 (AQP4). With so many symptoms in common, NMO can sometimes be confused with MS or other diseases. But these diseases are treated in different ways and early detection and treatment help ensure best outcomes. For these reasons, it is important to seek clinical care as soon as possible if symptoms occur.

Is there a possibility that NMO may be misdiagnosed as Multiple Sclerosis?

Yes. NMO is sometimes misdiagnosed as MS. The treatments for these distinct conditions can be very different, and recent reports suggest that some agents used to treat MS may be ineffective in NMO or actually make NMO symptoms worse.

What are the treatments for NMO relapses?

Acute NMO relapses or attacks are often treated with: – Corticosteroids (steroid treatment) – Plasmapheresis (the removal of antibodies from the blood stream) Plasmapheresis is often used if steroid treatment is ineffective. Some clinicians use plasmapheresis on a limited scale in cases where patients show poor tolerance for other agents used to prevent relapses.

Does one-step or monophasic NMO exist?

Usually NMO occurs as a series of episodes or relapses. However, in approximately 10% of patients, it appears that a form of monophasic NMO exists. These patients may suffer from an acute episode of optic neuritis in one or both eyes, and have other hallmark signs such as transverse myelitis, but have no relapses. However, it is difficult to tell if such patients are in a long remission period, or have the monophasic form of disease, so drug treatment is usually continued.

How are NMO attacks prevented?

The most common immunosuppressive agents used by NMO specialists to prevent NMO attacks include:

- Azathioprine (trade name, Immuran; oral)

- Mycophenolate (trade name, CellCept; oral)

- Rituximab (trade name, Rituxan; intravenous infusion)

Relapse prevention medications can be very helpful but may not be 100% effective.

Can tissues injured by NMO be repaired?

It is not known if the body can heal damage to the spinal cord, optic nerves or brain caused by NMO. It is possible that by preventing relapses, these tissues may repair themselves over time. However, it is also possible that tissue caused by NMO may be irreversible. Ongoing studies are being conducted to find ways to repair tissue damaged by NMO.

I haven’t had an NMO attack or flare-up for a long time, can I stop taking my medication or decrease its dosage?

Because NMO can stay in remission for long periods of time, even years, it is important to consult with your physician and/or an NMO specialist to determine ongoing therapy.

Should NMO patients receive standard vaccinations against infectious diseases?

Vaccinations are not known to cause NMO, and the benefits of immunization to protect against infection far outweigh risks. However, certain vaccines may not be advisable in the setting of specific types of immunosuppressive therapy. It is always best to consult with your physician and/or an NMO specialist to determine the best vaccine schedule in your case.

Can I get Stem-Cell treatment for NMO?

At the present time, the effectiveness of stem cell therapies for NMO is unknown. Consult with your physician and/or an NMO specialist.

What are B cells and why are they important?

B cells are a special type of white blood cell that produces antibody. Because the NMO-IgG antibody is believed to play a role in causing NMO disease or relapse, B cells that make NMO-IgG are considered targets for NMO therapy. For example, rituximab targets and eliminates certain types of B cells that may produce NMO-IgG antibody. B cell monitoring is often used for patients after receiving rituximab infusions, which are often four-to-six months apart.

Devic’s disease causes

Devics disease or NMO is an autoimmune disease though the exact cause for the autoimmunity is unknown. Autoimmune disorders occur when the body’s natural defenses against disease or invading organisms (such as bacteria), for unknown reasons, suddenly begin to attack healthy tissue, causing the symptoms of NMO. These defenses, for reasons not at all understood, attack proteins in the central nervous system, especially aquaporin-4. In some patients with Devic’s disease, especially those with the non-relapsing variant, antibodies to myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG-IgG) have been discovered. Patients who are seropositive for MOG differ in some respects from those with AQP4-IgG antibodies: they do not have as striking a predilection for women, attacks are less severe and recover better, optic neuritis tends to be associated with more swelling of the optic nerve head and occurs in the anterior optic nerve, whereas myelitis has a somewhat greater predilection for the caudal spinal cord. Devic’s disease may be immunologically heterogeneous.

Neuromyelitis optica is usually not inherited, but some people with NMO may have a history of autoimmune disorders in the family and may have another autoimmune condition themselves.

Greater than 95% of patients with Devic’s disease report no relatives with the disease, but approximately 3% report having other relatives with the condition. There is a strong association with a personal or family history of autoimmunity, which are present in 50% of cases.

Devic’s disease symptoms

Each person will experience different symptoms, which can range from mild to severe.

In many people with NMO, the spinal cord becomes swollen and irritated (inflamed). This is called transverse myelitis.

The optic nerve from the eye to the brain can also become inflamed – a condition called optic neuritis.

Some people may only experience transverse myelitis or optic neuritis but, if they have a specific antibody associated with Devic’s disease (AQP4) in their blood, they will be said to have NMO spectrum disorder (NMOSD).

Symptoms of optic neuritis and transverse myelitis include:

- eye pain

- loss of vision

- colors appearing faded or less vivid

- muscle weakness in the arms and legs

- nerve pain in the arms or legs – described as sharp, burning, shooting or numbing pain and increased sensitivity to cold and heat

- tight and painful muscle spasms in the arms and legs

- bladder, bowel and sexual problems

Devic’s disease can be one-off or relapsing. Some people may only have one attack of optic neuritis or transverse myelitis, with good recovery and no further relapses for a long time.

But in very severe cases, more attacks can follow. A relapse can take from several hours up to days to develop. These attacks can be unpredictable and it’s not understood what triggers them.

Optic neuritis

Optic neuritis is inflammation of the nerve that leads from the eye to the brain. It causes a reduction or loss of vision and can affect both eyes at the same time.

Other symptoms of neuritis include eye pain, which is usually made worse by movement, and reduced color vision where colors may appear ‘washed out’ or less vivid than usual.

Transverse myelitis

Transverse myelitis is inflammation of the spinal cord. It causes weakness in the arms and legs which can range from a mild ‘heavy’ feeling in one limb, to complete paralysis in all four limbs.

It may cause someone to have numbness, tingling or burning below the affected area of the spinal cord and be more sensitive to touch, cold and heat. There may also be tight and painful muscle contractions (known as tonic muscle spasms).

Devic’s disease diagnosis

Your doctor will perform a thorough evaluation to rule out other nervous system (neurological) conditions that have signs and symptoms similar to neuromyelitis optica. Distinguishing Devic’s disease from multiple sclerosis and other conditions ensures that you receive the most appropriate treatment.

To diagnose your condition, your doctor will review your medical history and symptoms and perform a physical examination. Your doctor may also perform:

- Neurological examination. A neurologist will examine your movement, muscle strength, coordination, sensation, memory and thinking (cognitive) functions, and vision and speech. An eye doctor (ophthalmologist) also may be involved in your examination.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). An MRI uses powerful magnets and radio waves to create a detailed view of your brain, optic nerves and spinal cord. Your doctor may be able to detect lesions or damaged areas in your brain, optic nerves or spinal cord.

- Blood tests. Your doctor might test your blood for the autoantibody Devic’s disease-IgG (also known as the aquaporin-4 autoantibody [AQP4-IgG] or NMO-immunoglobulin G [NMO-IgG]), which helps doctors distinguish Devic’s disease from MS and other neurological conditions. This test helps doctors make an early diagnosis of Devic’s disease. In general, the test for oligoclonal bands (a test that is often positive in MS) is usually negative in the spinal fluid in Devic’s disease. Oligoclonal bands are immunoglobulins (or antibodies), proteins produced by the immune system to fight off invaders like bacteria or viruses. A blood test known as the NMO-IgG (AQP4-IgG) blood test is positive in 70 percent of patients diagnosed with Devic’s disease. This test, in general, is negative in patients with multiple sclerosis. This has become an important marker for Devic’s disease and has helped improve our understanding of this disorder. A myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein (MOG-IgG) antibody test may also be requested to look for another inflammatory disorder that mimics Devic’s disease.

- MOG autoantibody — A minority of AQP4-seronegative patients with a phenotype of Devic’s disease has serum antibodies against MOG (myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein) 2. MOG autoantibodies may define an overlapping and possibly distinct clinical syndrome that often meets the clinical criteria for Devic’s disease but has some differences in features compared with AQP4 antibody-associated Devic’s disease or seronegative Devic’s disease, including 3:

- More likely to involve the optic nerve than the spinal cord

- More likely to present with simultaneous bilateral optic neuritis

- More likely to be monophasic or to have fewer relapses

- Less likely to be associated with other autoimmune disorders

- Proportionally more brainstem and cerebellar lesions, and fewer supratentorial lesions

- Spinal cord lesions mainly occur in the lower portion of the spinal cord

- The spectrum of disease may be wider and include acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), particularly in children

- The male-to-female ratio is close to 1:1, unlike the predominance of women in Devic’s disease with AQP4-IgG antibodies

- Proposed diagnostic criteria for MOG antibody-associated disorders require serum positivity for MOG-IgG by cell-based assay and a clinical presentation consistent with central nervous system demyelination (ie, acute disseminated encephalomyelitis (ADEM), optic neuritis, transverse myelitis, a brain or brainstem demyelinating syndrome, or any combination of these), and exclusion of an alternative diagnosis 4. In the absence of serum, positivity for MOG-IgG in the CSF allows fulfillment of the criteria. In a series of 51 patients, transient seropositivity favored a lower risk of relapse 4.

- MOG autoantibody — A minority of AQP4-seronegative patients with a phenotype of Devic’s disease has serum antibodies against MOG (myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein) 2. MOG autoantibodies may define an overlapping and possibly distinct clinical syndrome that often meets the clinical criteria for Devic’s disease but has some differences in features compared with AQP4 antibody-associated Devic’s disease or seronegative Devic’s disease, including 3:

- Lumbar puncture (spinal tap). During this test, your doctor will insert a needle into your lower back to remove a small amount of spinal fluid. Doctors test the levels of immune cells, proteins and antibodies in the fluid. This test may help your doctor differentiate Devic’s disease from MS. In Devic’s disease, the spinal fluid may show markedly elevated white blood cells during Devic’s disease episodes, greater than normally seen in MS, although this doesn’t always happen.

- Stimuli response test. To learn how well your brain responds to stimuli such as sounds, sights or touch, you’ll undergo a test called evoked potentials (they may also be called evoked response tests). During these tests, doctors attach small wires (electrodes) to your scalp and, in some cases, your earlobes, neck, arm, leg and back. Equipment attached to the electrodes records your brain’s responses to stimuli. These tests help your doctor to find lesions or damaged areas in the nerves, spinal cord, optic nerve, brain or brainstem.

Is the NMO IgG antibody test foolproof?

No. Most NMO IgG tests list a 5-10% chance of a false-positive result, or a 20-30% chance of false negative result. The most commonly used laboratory test for NMO antibody was created in 2000 at the Mayo Clinic.

Devic’s disease treatment

There’s no cure for Devic’s disease, but treatments can help to ease symptoms, prevent future relapses and slow down the progression of the disease. NMO treatment involves therapies to reverse recent symptoms and prevent future attacks.

You may be prescribed:

- Steroids to reduce the inflammation

- Medication to suppress your immune system and ease your symptoms, such as azathioprine, mycophenolate or methotrexate

- Rituximab, a newer type of drug called a biological, to reduce inflammation.

- In 2019, Soliris (eculizumab) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for the treatment of Devic’s disease in adult patients who are anti-aquaporin-4 (AQP4) antibody positive.

Since Devic’s disease is a relatively rare disease, there are no large-scale studies of treatment for Devic’s disease. Treatment for an acute attack of Devic’s usually begins with intravenous steroids followed by oral steroids. If the steroids are not effective, a treatment known as plasmapheresis is often used. This therapy cleans the antibodies from the blood by circulating it through a machine, similar to the way in which dialysis works.

Longer-term treatment medications may include:

- Steroids

- Immune-suppressing medicines such as azathioprine

- Chemotherapeutics such as mitoxantrone (Novantrone®)

- Other immune-suppressing medications have also been used (e.g., rituximab)

Devic’s disease does not appear to respond to standard medications for multiple sclerosis. It is important therefore to identify this diagnosis so that more effective treatment for this problem can be used early in the disorder.

Rehabilitation techniques, such as physiotherapy, can also help if you have problems with your mobility.

Do these treatments have dangerous side effects?

As with the treatment of any disease, certain NMO treatments can have side effects, including serious adverse events such as infection. However, recent reports suggest that treatment efficacy is improving, and the benefits far outweigh the negative side effects in preventing or resolving severe attacks. It is always best to consult with your physician and/or an NMO specialist to determine which treatment regimen may be best for you.

If taking immunosuppressive therapy, is it OK to take over-the-counter herbal remedies and/or vitamin supplements?

It is always best to consult with your physician and/or an NMO specialist regarding over-the-counter herbal remedies and/or vitamin supplements in relation to your NMO treatment regimen.

What are key points to keep in mind if I am taking immunosuppressive therapy?

All immunosuppressive therapies reduce the ability of your immune system to fight against infection and cancer. In addition, wound healing may be slower, and dental health compromised. Preventative exams such as mammograms, pap smears, dermatology full-body exams, and dental hygiene should be done regularly. It is also important to pay attention to public health hygiene by considering the basic rules of protecting yourself against transmissible diseases:

- Wash your hands regularly and thoroughly with soap and water

- Avoid touching your eyes, nose, mouth, or face

- Avoid interacting with people who may be sick, coughing or sneezing

- If you feel a cold or fever coming on, consult your physician immediately

Acute attacks

In the early stage of an neuromyelitis optica attack, your doctor may give you a corticosteroid medication, methylprednisolone (Solu-Medrol), through a vein in your arm (intravenously). You’ll be given the medication for about five days, and then the medication will be tapered off slowly over several days.

Plasma exchange is frequently recommended as the first or second treatment, usually in addition to steroid therapy. In this procedure, some blood is removed from your body, and blood cells are mechanically separated from fluid (plasma). Doctors mix your blood cells with a replacement solution and return the blood into your body. Doctors can also help manage other symptoms you may experience, such as pain or muscle problems.

Symptom treatment may also involve the use of low doses of carbamazepine to control paroxysmal (sudden) tonic spasms that often occur during attacks of Devic’s disease and antispasticity agents to treat long term complication of spasticity that frequently develops in those with permanent motor deficits.

Preventing future attacks

Doctors may recommend that you take a lower dose of corticosteroids for an extensive period of time to prevent future neuromyelitis optica attacks and relapses.

Your doctor may also recommend taking a medication that suppresses your immune system, in addition to corticosteroids, to prevent future neuromyelitis optica attacks. Immunosuppressive medications that may be prescribed include azathioprine (Imuran, Azasan), mycophenolate mofetil (Cellcept) or rituximab (Rituxan). Typically, azathioprine or mycophenolate mofetil are prescribed along with low doses of corticosteroids. Rituximab has been shown to be helpful in retrospective studies, including in patients who fail first-line immunosuppressive treatments. Immunomodulatory drugs for multiple sclerosis are ineffective, and in the case of interferon beta, there is some evidence that suggest that it may be harmful.

Devic’s disease prognosis

The natural history of Devic’s disease is one of stepwise deterioration due to accumulating visual, motor, sensory, and bladder deficits from recurrent attacks. Most acute attacks or relapses worsen over days to a nadir and recover over several weeks to months with significant sequelae. Predictors of a worse prognosis include the number of relapses within the first two years, the severity of the first attack, older age at disease onset, and (perhaps) an association with other autoimmune disorders including autoantibody status 5. These prognostic factors need to be confirmed in larger independent prospective studies.

Mortality rates are high in Devic’s disease, most frequently secondary to neurogenic respiratory failure, which occurs with extension of cervical lesions into the brainstem or from primary brainstem lesions 6. Cohort studies of North American, Brazilian, and French West Indies populations reported mortality rates of 32 percent, 50 percent, and 25 percent, respectively in Devic’s disease 7. These studies may be biased towards more severe cases. Progress in the diagnosis and treatment of Devic’s disease is expected to decrease mortality rates.

The aquaporin-4 (AQP4) autoantibody (NMO-immunoglobulin G [IgG]) may be a marker for disease course and prognosis 8, though the available data are inconsistent 9. In patients with recurrent optic neuritis, retrospective evidence suggests that AQP4-IgG seropositivity is associated with poor visual outcome and development of Devic’s disease 10. A prospective study of 29 patients presenting with longitudinally extensive spinal cord lesions found 55 percent of the patients seropositive for AQP4-IgG relapsed within one year or converted to Devic’s disease, while none of seronegative patients relapsed 11. In contrast, a subsequent report noted that seronegative and seropositive Devic’s disease were similar in terms of relapse rate, severity, and long-term outcomes 9. The discrepancy in these results may be due in part to small numbers of patients with seronegative Devic’s disease and to differences in the sensitivities of the AQP4 antibody assays.

There are only limited and retrospective data on the relationship of Devic’s disease and pregnancy. These suggest that Devic’s disease is associated with an increased risk of miscarriage 12, and that the annualized relapse rate of Devic’s disease is increased in the first three to six months of the postpartum period 13.

Devic’s disease life expectancy

The severity of impairment and life expectancy may depend on the severity of the first (or only) episode, the number of relapses within the first two years, and a person’s age when the disease begins. In general, the outlook (prognosis) is thought to be worse for people who have severe symptoms during the first episode, have many relapses within a shorter amount of time, and/or are older when the disease begins 14.

For people with the relapsing form (90% of those with the disease), each episode causes more damage to the nervous system 14. Often this eventually leads to permanent muscle weakness, paralysis, and/or vision loss within 5 years 15. People with the monophasic form (those who experience one episode) can also have lasting impairment of muscle function and vision 16.

The disease reportedly may ultimately be fatal in 25-50% of people, with loss of life most commonly due to respiratory failure. However, the life expectancy varies from person to person 14.

References- Neuromyelitis Optica Spectrum Disorder. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/neuromyelitis-optica/

- Wang JJ, Jaunmuktane Z, Mummery C, Brandner S, Leary S, Trip SA. Inflammatory demyelination without astrocyte loss in MOG antibody-positive NMOSD. Neurology. 2016;87(2):229–231. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002844

- Narayan R, Simpson A, Fritsche K, et al. MOG antibody disease: A review of MOG antibody seropositive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2018;25:66–72. doi:10.1016/j.msard.2018.07.025

- López-Chiriboga AS, Majed M, Fryer J, et al. Association of MOG-IgG Serostatus With Relapse After Acute Disseminated Encephalomyelitis and Proposed Diagnostic Criteria for MOG-IgG-Associated Disorders. JAMA Neurol. 2018;75(11):1355–1363. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1814

- Kitley J, Leite MI, Nakashima I, et al. Prognostic factors and disease course in aquaporin-4 antibody-positive patients with neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder from the United Kingdom and Japan. Brain. 2012;135(Pt 6):1834–1849. doi:10.1093/brain/aws109

- Sellner J, Boggild M, Clanet M, et al. EFNS guidelines on diagnosis and management of neuromyelitis optica. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(8):1019–1032. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03066.x

- Cabre P, González-Quevedo A, Bonnan M, et al. Relapsing neuromyelitis optica: long term history and clinical predictors of death. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2009;80(10):1162–1164. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2007.143529

- Weinstock-Guttman B, Miller C, Yeh E, et al. Neuromyelitis optica immunoglobulins as a marker of disease activity and response to therapy in patients with neuromyelitis optica. Mult Scler. 2008;14(8):1061–1067. doi:10.1177/1352458508092811

- Jiao Y, Fryer JP, Lennon VA, et al. Updated estimate of AQP4-IgG serostatus and disability outcome in neuromyelitis optica. Neurology. 2013;81(14):1197–1204. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a6cb5c

- Matiello M, Lennon VA, Jacob A, et al. NMO-IgG predicts the outcome of recurrent optic neuritis. Neurology. 2008;70(23):2197–2200. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000303817.82134.da

- Weinshenker BG, Wingerchuk DM, Vukusic S, et al. Neuromyelitis optica IgG predicts relapse after longitudinally extensive transverse myelitis. Ann Neurol. 2006;59(3):566–569. doi:10.1002/ana.20770

- Nour MM, Nakashima I, Coutinho E, et al. Pregnancy outcomes in aquaporin-4-positive neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Neurology. 2016;86(1):79–87. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000002208

- Kim W, Kim SH, Nakashima I, et al. Influence of pregnancy on neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorder. Neurology. 2012;78(16):1264–1267. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e318250d812

- Neuromyelitis optica spectrum disorders. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/neuromyelitis-optica-spectrum-disorders

- Neuromyelitis Optica Information Page. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/Disorders/All-Disorders/Neuromyelitis-Optica-Information-Page

- Neuromyelitis optica. https://ghr.nlm.nih.gov/condition/neuromyelitis-optica