Endometrial cancer

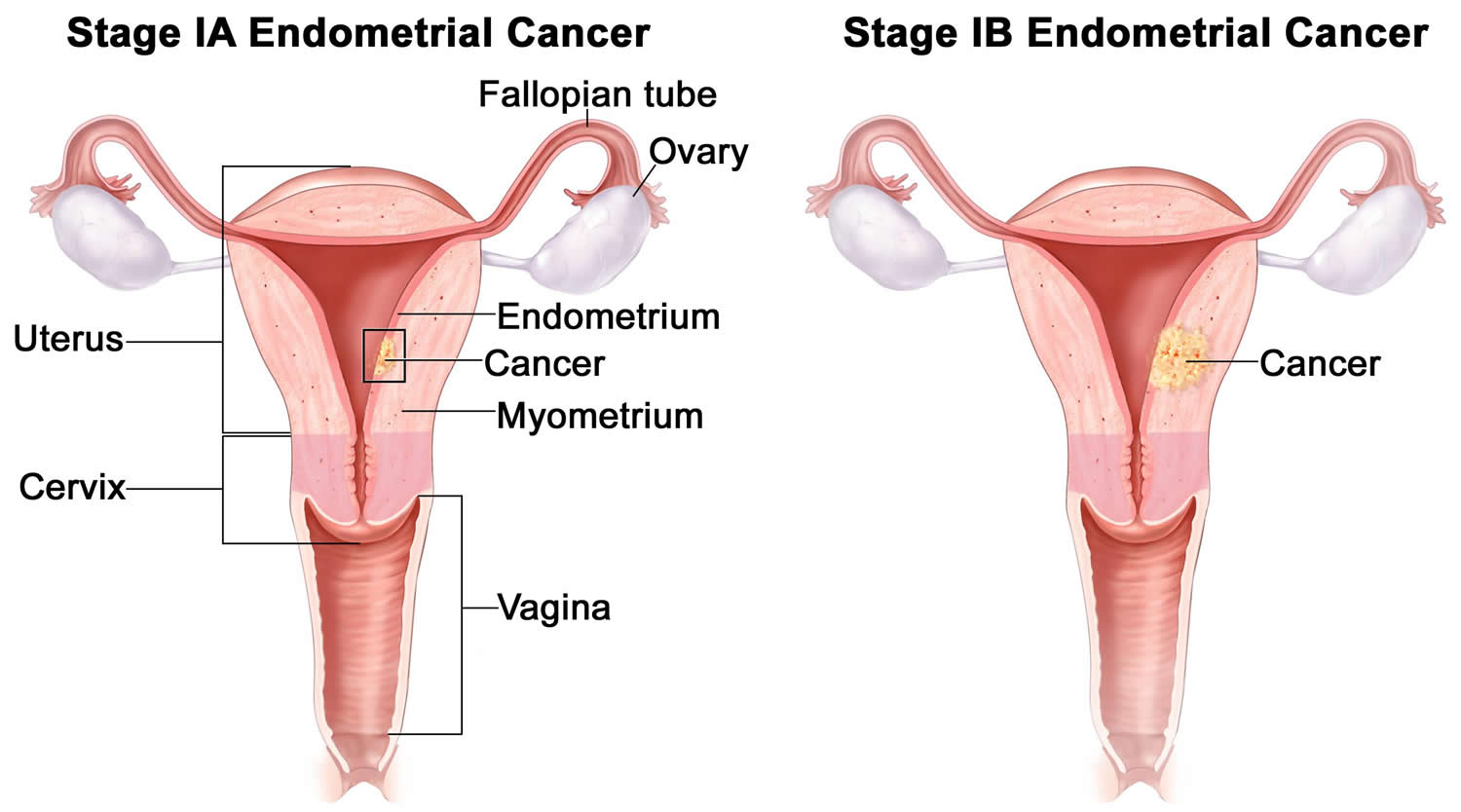

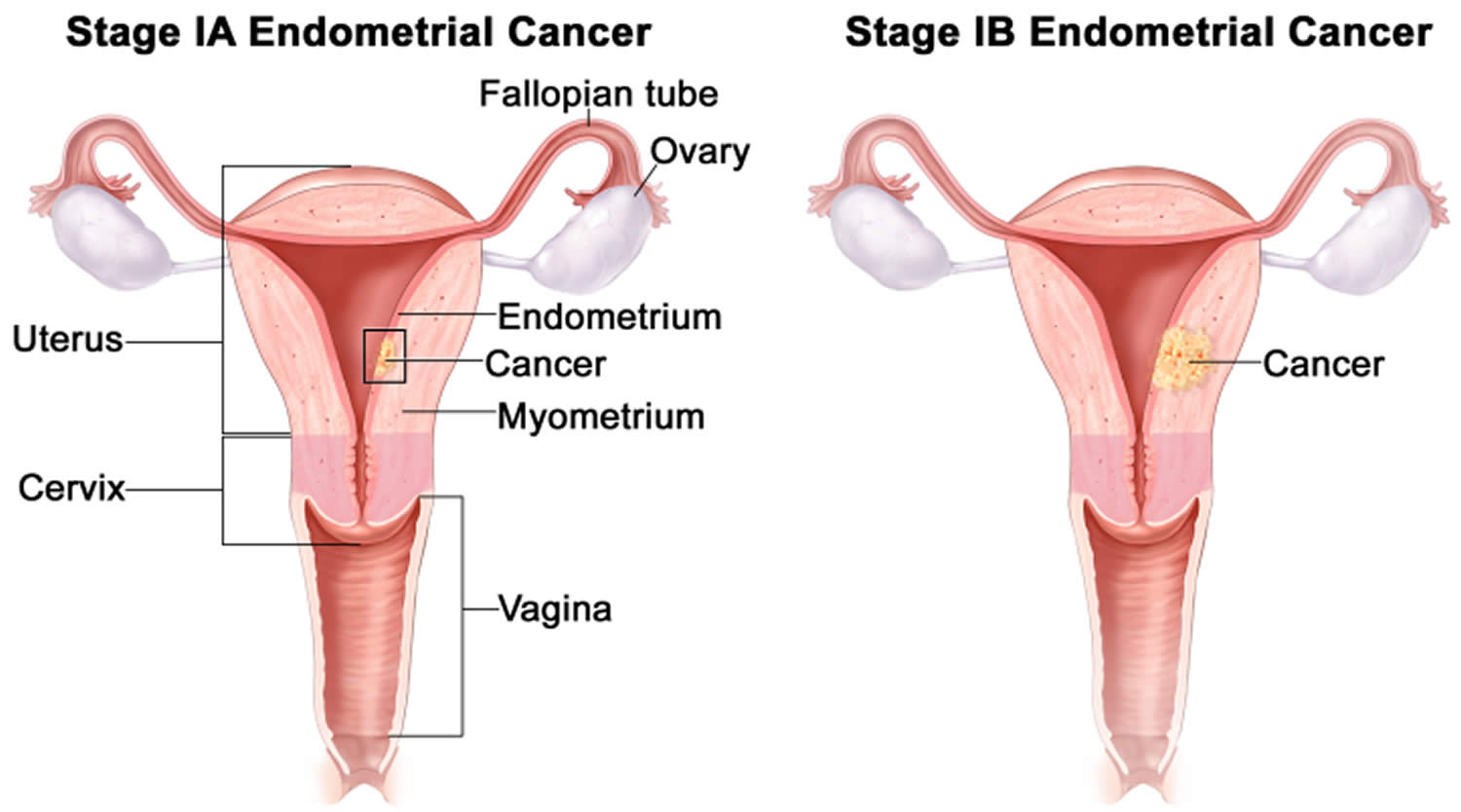

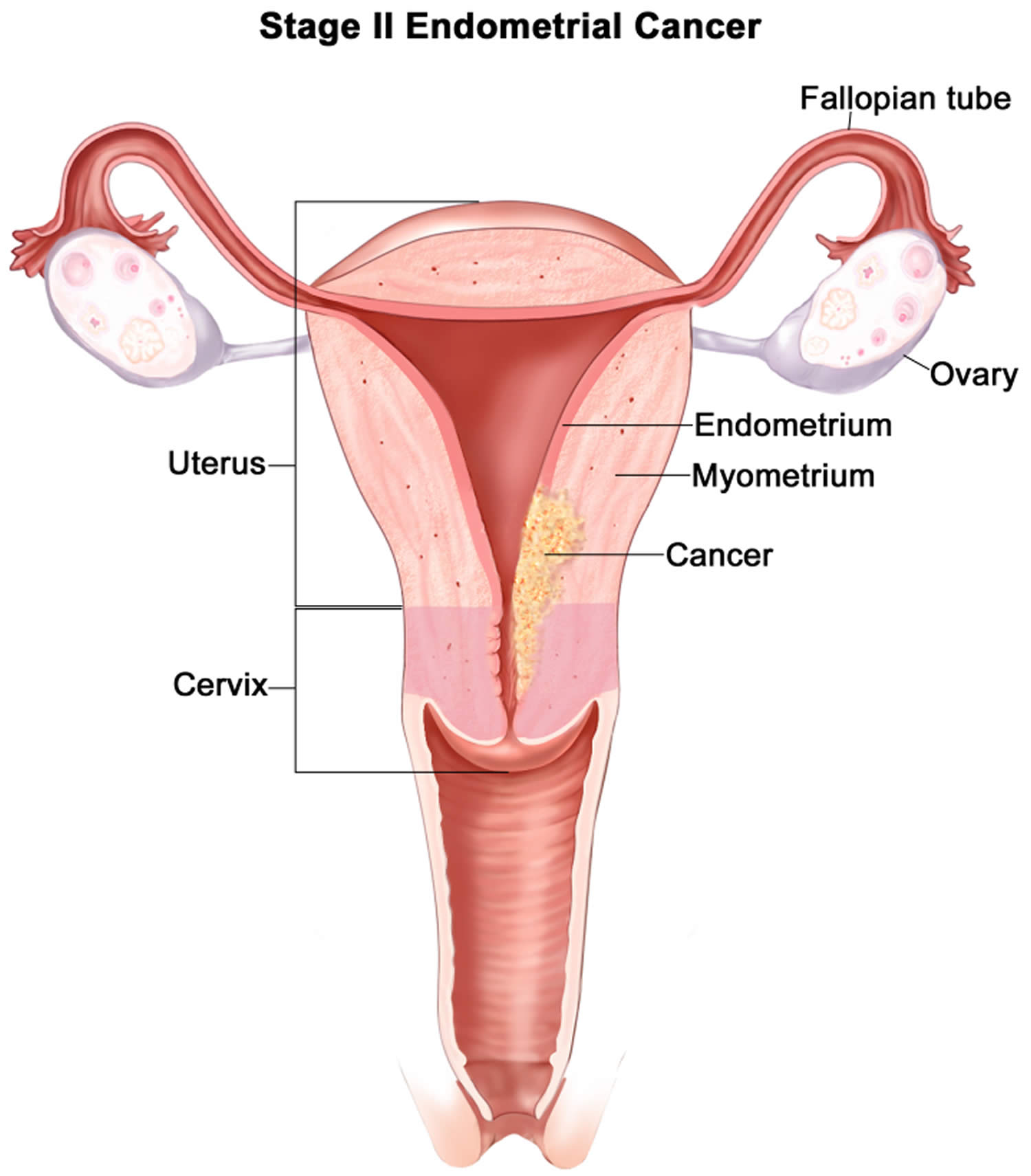

Endometrial cancer begins in the layer of cells that form the lining (the endometrium) of the uterus (see Figures 1 and 3). The uterus is part of the female reproductive system. It is a hollow, pear-shaped, muscular organ in the pelvis, where a fetus grows. Endometrial cancer is often detected at an early stage, because it frequently produces abnormal vaginal bleeding such as vaginal bleeding after menopause or bleeding between periods, which prompts women to see their health care providers. If endometrial cancer is discovered early, removing the uterus surgically often cures endometrial cancer.

Endometrial cancer is the fourth most common cancer in women in the United States after breast, lung, and colorectal cancers 1.

In the United States, cancer of the endometrium (the lining of the uterus) is the most common cancer of the female reproductive organs. The American Cancer Society estimates for cancer of the uterus in the United States for 2023 are 2, 3:

- New cases: About 66,200 new cases of cancer of the body of the uterus (uterine body or corpus) will be diagnosed.

- Deaths: About 13,030 women will die from cancers of the uterine body.

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 81.3%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Endometrial cancer deaths as a percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 2.1%.

- Rate of New Cases and Deaths per 100,000: The rate of new cases of uterine cancer was 27.8 per 100,000 women per year. The death rate was 5.0 per 100,000 women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2015–2019 cases and deaths.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing Cancer: Approximately 3.1 percent of women will be diagnosed with uterine cancer at some point during their lifetime, based on 2017–2019 data.

- In 2019, there were an estimated 822,388 women living with uterine cancer in the United States. There are more than 600,000 survivors of endometrial cancer in the US today.

These estimates include both endometrial cancers and uterine sarcomas. Up to 10% of uterine body cancers are sarcomas, so the actual numbers for endometrial cancer cases and deaths are slightly lower than these estimates.

Endometrial cancer affects mainly post-menopausal women. The average age of women diagnosed with endometrial cancer is 60. It’s uncommon in women under the age of 45.

Endometrial cancer is more common in Black women than white women, and Black women are more likely to die from it.

Endometrial cancer is often detected at an early stage because it frequently produces abnormal vaginal bleeding. If endometrial cancer is discovered early, removing the uterus surgically often cures endometrial cancer.

Your particular treatment plan depends on the type of cancer and your overall health. Treatment for endometrial cancer is usually with surgery to remove the uterus, fallopian tubes and ovaries. Another option is radiation therapy with powerful radiation energy. Drug treatments for endometrial cancer include chemotherapy with powerful drugs and hormone therapy to block hormones that cancer cells rely on. Other options might be targeted therapy with drugs that attack specific weaknesses in the cancer cells and immunotherapy to help your immune system fight cancer.

Are endometrial cancer and uterine cancer the same?

Uterine cancer can refer to either endometrial cancer, uterine sarcoma or other rare forms of cancer that can arise in your uterus (womb). But people often treat the terms “endometrial cancer” and “uterine cancer” the same. That’s because endometrial cancers are much more common than other cancers that can form in your uterus. Uterine sarcomas are very rare. Uterine sarcoma develops in the myometrium, the muscle wall of your uterus.

Uterus and endometrium

The uterus is a hollow, muscular organ shaped somewhat like an inverted pear. The uterus receives the embryo that develops from an oocyte fertilized in the uterine tube, and sustains its development.

In its nonpregnant, adult state, the uterus is about 7 centimeters long, 5 centimeters wide (at its broadest point), and 2.5 centimeters in diameter. The size of the uterus changes greatly during pregnancy and it is somewhat larger in women who have been pregnant. The uterus is located medially in the anterior part of the pelvic cavity, superior to the vagina, and usually bends forward over the urinary bladder (see Figure 3).

The uterus has 2 main parts:

- The upper part of the uterus is called the body or the corpus. Corpus is the Latin word for body.

- The cervix is the lower end of the uterus that joins it to the vagina.

When people talk about cancer of the uterus, they usually mean cancers that start in the body of the uterus, not the cervix. Cervical cancer is a separate kind of cancer.

The upper two-thirds or body (corpus), of the uterus has a domeshaped top called the fundus (see Figure 1). The uterine tubes (also called Fallopian tubes) connect at the upper lateral edges of the uterus. The lower third of the uterus is called the cervix. This tubular part extends downward into the upper part of the vagina. The cervix surrounds the opening called the cervical orifice, through which the uterus opens to the vagina.

The uterine wall is thick and has 3 layers (Figure 1):

- The endometrium, the inner mucosal layer, is covered with columnar epithelium and contains abundant tubular glands (see Figure 3). During a woman’s menstrual cycle, hormones cause the endometrium to change. Estrogen causes the endometrium to thicken so that it could nourish an embryo if pregnancy occurs. If there is no pregnancy, estrogen is produced in lower amounts and more of the hormone called progesterone is made. This causes the endometrial lining to shed from the uterus and become the menstrual flow (period). This cycle repeats until menopause.

- The myometrium, a thick, middle, muscular layer, consists largely of bundles of smooth muscle cells. This thick layer of muscle is needed to push the baby out during birth. During the monthly female menstrual cycles and during pregnancy, the endometrium and myometrium change extensively.

- The perimetrium also called the serosa consists of an outer serosal layer, which covers the body of the uterus and part of the cervix.

During a woman’s menstrual cycle, hormones cause the endometrium to change. During the early part of the cycle, before the ovaries release an egg (ovulation), the ovaries produce hormones called estrogens. Estrogen causes the endometrium to thicken so that it could nourish an embryo if pregnancy occurs. If there is no pregnancy, estrogen is produced in lower amounts and more of the hormone called progesterone is made after ovulation. This prepares the innermost layer of the lining to shed. By the end of the cycle, the endometrial lining is shed from the uterus and becomes the menstrual flow (period). This cycle repeats until the woman’s goes through menopause (change of life).

The uterus is supported by the muscular floor of the pelvis and folds of peritoneum that form supportive ligaments around the organ, as they do for the ovary and uterine tube. The broad ligament has two parts: the mesosalpinx mentioned earlier and the mesometrium on each side of the uterus. The cervix and superior part of the vagina are supported by cardinal (lateral cervical) ligaments extending to the pelvic wall. A pair of uterosacral ligaments attaches the posterior side of the uterus to the sacrum, and a pair of round ligaments arises from the anterior surface of the uterus, passes through the inguinal canals, and terminates in the labia majora.

As the peritoneum folds around the various pelvic organs, it creates several dead-end recesses and pouches (extensions of the peritoneal cavity). Two major ones are the vesicouterine pouch, which forms the space between the uterus and urinary bladder, and rectouterine pouch between the uterus and rectum (see Figure 2).

The uterine blood supply to the uterus is particularly important to the menstrual cycle and pregnancy. A uterine artery arises from each internal iliac artery and travels through the broad ligament to the uterus (Figure 4). It gives off several branches that penetrate into the myometrium and lead to arcuate arteries. Each arcuate artery travels in a circle around the uterus and anastomoses with the arcuate artery on the other side. Along its course, it gives rise to smaller arteries that penetrate the rest of the way through the myometrium, into the endometrium, and give off spiral arteries. The spiral arteries wind tortuously between the endometrial glands toward the surface of the mucosa. They rhythmically constrict and dilate, making the mucosa alternately blanch and flush with blood.

Figure 1. Uterus

Figure 2. Uterus location

Figure 3. Endometrium of the uterus and its blood supply

Figure 4. Blood supply to the uterus

Endometrium function

The endometrium changes throughout the menstrual cycle in response to hormones. During the first part of the cycle, the hormone estrogen is made by the ovaries. Estrogen causes the lining to grow and thicken to prepare the uterus for pregnancy. In the middle of the cycle, an egg is released from one of the ovaries (ovulation).

Following ovulation, levels of another hormone called progesterone begin to increase. Progesterone prepares the endometrium to receive and nourish a fertilized egg. If pregnancy does not occur, estrogen and progesterone levels decrease. The decrease in progesterone triggers menstruation, or shedding of the lining. Once the lining is completely shed, a new menstrual cycle begins.

Figure 5. Ovarian activity during the Menstrual cycle

Footnote: Major events in the female menstrual cycle. (a) Plasma hormonal concentrations of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH) affect follicle maturation in the ovaries. (b) Plasma hormonal concentrations of estrogen and progesterone influence changes in the uterine lining.

Endometrial hyperplasia

Endometrial hyperplasia is a common condition in which the endometrium (lining of the uterus) is abnormally thick. The uterus is part of the female reproductive system. It is a hollow, pear-shaped, muscular organ in the pelvis, where a fetus grows. Endometrial hyperplasia is defined as a proliferation of endometrial glands of irregular size and shape that results in a greater than normal gland-to-stroma ratio 4. Endometrial hyperplasia is caused by too much exposure to exogenous or endogenous estrogen along with a relative deficiency of progesterone 5. Both estrogen and progesterone hormones play roles in the menstrual cycle. Estrogen makes the cells grow, while progesterone signals the shedding of the cells. A hormonal imbalance estrogen and progesterone hormones in can produce too many cells or abnormal cells. Endometrial hyperplasia is not cancer, but in some cases, if it’s not treated, has the propensity to develop into endometrial cancer or cancer of the uterus 6. Endometrial hyperplasia is believed to be a precursor of cancer of the uterus or endometrial carcinoma, which is the most common gynecologic cancer and the fourth most common cancer in women in the United States 7.

Endometrial hyperplasia is most frequently diagnosed in postmenopausal women, but women of any age can be at risk if they are exposed to a source of unopposed estrogen 8. Endometrial hyperplasia is increasingly seen in young women with chronic anovulation due to polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or obesity 9.

Endometrial hyperplasia usually occurs after menopause, when ovulation stops and progesterone is no longer made 10. Endometrial hyperplasia can also develop during perimenopause, when ovulation may not occur regularly. There may be high levels of estrogen and not enough progesterone in other situations, including when a woman 10:

- uses medications that act like estrogen, such as tamoxifen for cancer treatment

- uses estrogen for hormone therapy and does not use progesterone or progestin if she still has a uterus

- has irregular menstrual periods, especially associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) or infertility

- has obesity – body mass index (BMI) of 27 or more

The main symptom of endometrial hyperplasia is abnormal menstrual bleeding. However, abnormal uterine bleeding can be a symptom for many things. Your doctor can perform an exam and tests to diagnose the cause of the abnormal uterine bleeding. A transvaginal ultrasound measures your endometrium. It uses sound waves to see if the layer is average or too thick. A thick layer can indicate endometrial hyperplasia. Endometrial hyperplasia is typically diagnosed by endometrial biopsy or curettage when a woman is noted as suffering from abnormal uterine bleeding 11. Your doctor will take a biopsy of your endometrium cells to determine if cancer is present.

Treatment options for endometrial hyperplasia depend on what type you have. The most common treatment is progestin. This can be taken in several forms, including pill, shot, vaginal cream, or intrauterine device.

Atypical types of endometrial hyperplasia, especially complex, increase your risk of getting cancer. If you have these types, you might consider a hysterectomy. This is a surgery to remove your uterus. Doctors recommend this if you no longer want to become pregnant.

There are also a number of more conservative treatments for younger women who do not wish to have a hysterectomy. Your doctor will help you decide which treatment option is best for you.

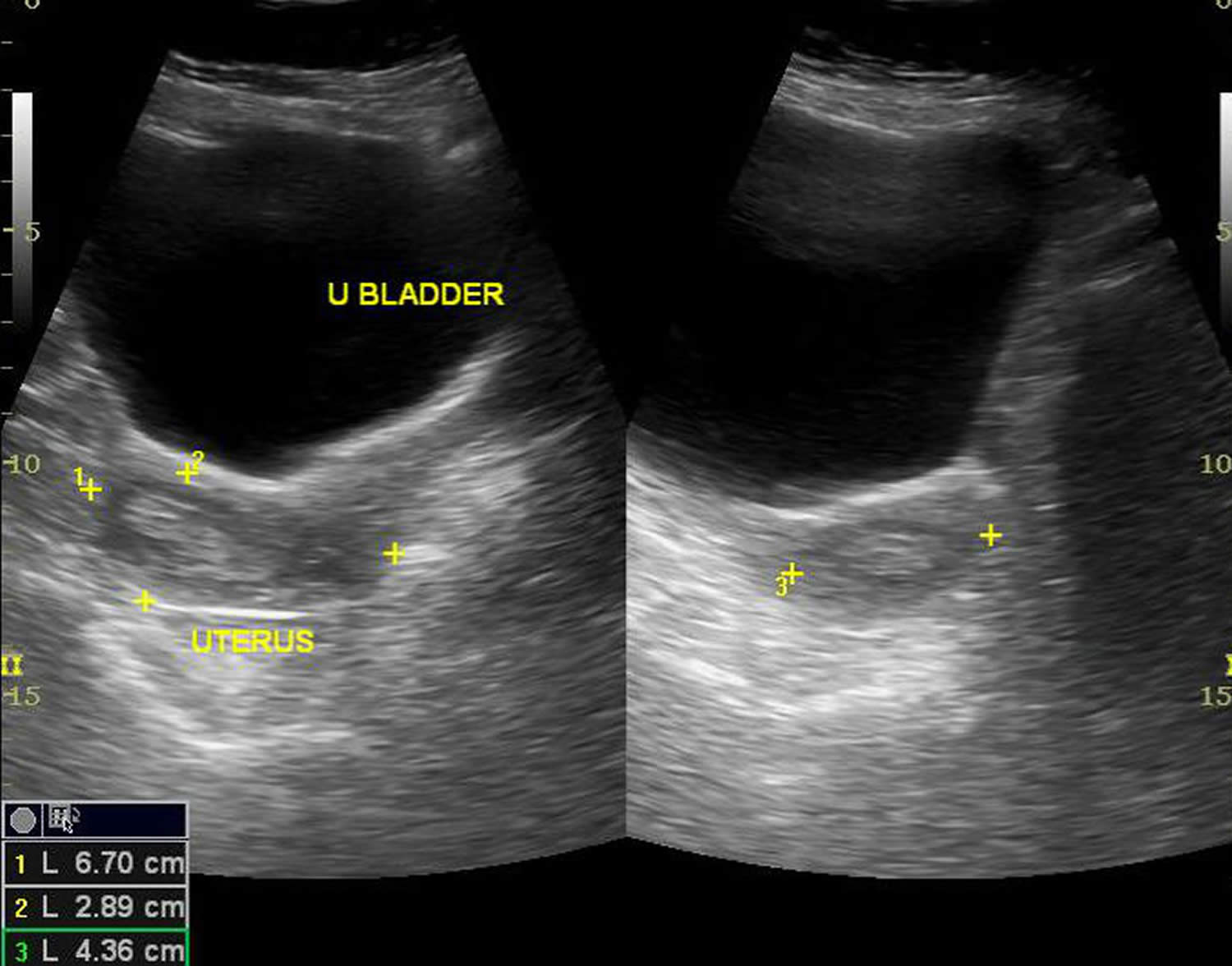

Figure 6. Endometrial hyperplasia ultrasound

Footnote: Endometrial thickness is 12 mm. Multiple cystic spaces are noted within. Solid areas are echogenic. Margins of endometrial lining was well-defined. No significant flow signals seen. Myometrium does not show focal lesion. Either of ovaries could not be localized.

[Source 12 ]Types of endometrial hyperplasia

The types of endometrial hyperplasia vary by the amount of abnormal cells and the presence of cell changes. According to the World Health Organization endometrial hyperplasia classification system in 1994 (WHO94), endometrial hyperplasia can be divided into 4 categories 13:

- Simple endometrial hyperplasia – Increased number of endometrial glands but regular glandular architecture.

- Complex endometrial hyperplasia – Crowded irregular endometrial glands.

- Simple atypical endometrial hyperplasia – Simple hyperplasia with presence of cytologic atypia (prominent nucleoli and nuclear pleomorphism).

- Complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia – Complex hyperplasia with cytologic atypia

The World Health Organization endometrial hyperplasia classification system 1994 (WHO94) was based on the original retrospective study of 170 patients by Kurman et al 13 who found that lesions with varying degrees of complexity and presence of atypia, when left untreated for a mean of 13 years, progressed to adenocarcinoma at different rates. Simple endometrial hyperplasia was associated with a 1% rate of progression to cancer, complex endometrial hyperplasia 3% rate of progression, simple atypical endometrial hyperplasia 8% rate of progression, whereas complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia had a 29% rate of progression to cancer 13.

Not only does the concern exist for atypical endometrial hyperplasia progressing to invasive cancer if untreated, but numerous studies found coexisting carcinoma at rates ranging from 17-56% 11, 14. A prospective Gynecologic Oncology Group study found that 306 patients with preoperative biopsies that diagnosed atypical endometrial hyperplasia had concurrent invasive adenocarcinoma in 42.6% of hysterectomy specimen 15. Part of the difficulty in diagnosing concurrent carcinoma is due to lack of reproducibility in diagnosing hyperplasia, especially atypical hyperplasia versus adenocarcinoma among even expert gynecologic pathologists. Studies report only 40-69% interobserver agreement for endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial cancer 16.

Due to the poor reproducibility of diagnosis, and confusion regarding optimal clinical management, gynecologic pathologists proposed a simpler classification of endometrial hyperplasia versus endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) using a computerized morphometric analysis. Endometrial hyperplasia is benign hyperplasia and correlates closely to simple hyperplasia, whereas endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) is a pre-malignant condition 17. Endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) is defined as when the volume of glandular crowding is greater than the stromal volume, the presence of cytologic alterations, a lesion larger than 1 mm, and exclusion of mimics or carcinoma 17. Classification as complex atypical hyperplasia (WHO’94) or as endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) had similar sensitivities and negative predictive values for coexisting endometrial cancer 18. Others found the endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) classification to be better at predicting progression to cancer. Thus in 2014 the WHO formally adopted the simplified classification of endometrial hyperplasia into 2 categories.

World Health Organization endometrial hyperplasia classification system in 2014 (Table 1) 19:

- Hyperplasia without atypia or benign endometrial hyperplasia. Hyperplasias without atypia (benign endometrial hyperplasia) exhibit no relevant genetic changes. They are benign changes and will regress again after the endocrine milieu (physiological gestagen levels) has normalized. In a few cases (1–3 %), progression to invasive disease may occur if the endocrine disorder (long-term estrogen dominance or relative or absolute gestagen deficiency) persists over the long term.

- Endometrial Intraepithelial Neoplasia (EIN) or atypical endometrial hyperplasia. Atypical endometrial hyperplasias exhibit many of the mutations typical for invasive endometrioid endometrial cancer 20. In up to 60 % of cases, patients have coexisting invasive cancer or are at extremely high risk of developing invasive cancer (see Table 1).

This reduction to 2 categories was not only due to the need to do away with the confusing multitude of terms currently in use. Rather, it reflects a new understanding of molecular genetic changes.

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and the Society of Gynecologic Oncology Committee opinion 2015 also recommend the use of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) schema for a more clear terminology to distinguish the two clinicopathologic categories 7, 21. Not only does this classification reflect clinical outcome, but also underlying genetic and molecular changes 22.

The implications for treatment are obvious: hyperplasias without atypia should generally be treated conservatively (normalization of the cycle through weight loss, metformin; oral contraceptives; cyclical gestagens; gestagen IUD). Preventive hysterectomy should only be considered in exceptional cases (e.g., extreme obesity without any prospect of weight loss) 23. The surgery should be done as a total hysterectomy, i.e., it must include removal of the cervix 23.

Treatment of atypical hyperplasia or endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia should generally consist of total (not supracervical) hysterectomy 23. Conservative treatment with high-dose gestagens and close histological monitoring should only be considered in exceptional cases (when the patient wants to have children, satisfactory compliance) 24, 23.

Table 1. New World Health Organization (WHO) classification of endometrial hyperplasia

| New term | Synonyms | Genetic changes | Coexistent invasive endometrial carcinoma | Progression to invasive carcinoma |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperplasia without atypia | Benign endometrial hyperplasia; simple non-atypical endometrial hyperplasia; complex non-atypical endometrial hyperplasia; simple endometrial hyperplasia without atypia; complex endometrial hyperplasia without atypia | Low level of somatic mutations in scattered glands with morphology on HE staining showing no changes | < 1 % | RR: 1.01–1.03 |

| Atypical hyperplasia or endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia | Complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia; simple atypical endometrial hyperplasia; endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) | Many of the genetic changes typical for endometrioid endometrial cancer are present, including: micro satellite instability; PAX2 inactivation; mutation of PTEN, KRAS and CTNNB1 (β-catenin) | 25–33 % 19 59 % 25 | RR: 14–45 |

Footnotes: RR = Relative Risk. Relative risk is a ratio of the probability of an event occurring in the exposed group versus the probability of the event occurring in the non-exposed group. Relative Risk = (Probability of event in exposed group) / (Probability of event in not exposed group) 26. For example, atypical hyperplasia or endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) has a Relative Risk of 14 to 45 times more likely to progress to invasive endometrial cancer in this study compared to those without atypical hyperplasia or endometrioid intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) in the study.

[Source 22 ]Endometrial hyperplasia signs and symptoms

The most common of endometrial hyperplasia is abnormal menstrual bleeding. If you have any of the following, you should see your doctor or an obstetrician–gynecologist (ob-gyn):

- Menstrual bleeding that is heavier or longer lasting than usual.

- Menstrual cycles (amount of time between periods) that are shorter than 21 days (counting from the first day of the menstrual period to the first day of the next menstrual period).

- Menstrual bleeding between menstrual periods.

- Not having a period (pre-menopause).

- Any bleeding after menopause.

Endometrial hyperplasia causes

Endometrial hyperplasia is the result of chronic unopposed estrogenic stimulation of the endometrial tissue with a relative deficiency of the counterbalancing effects of progesterone 27. The causes of estrogen excess could be endogenous or exogenous. For example, if ovulation does not occur, progesterone is not made, and the lining is not shed. The endometrium may continue to grow in response to estrogen. The cells that make up the lining may crowd together and may become abnormal. This condition, called hyperplasia, can lead to cancer.

You are more likely to have endometrial hyperplasia if you have gone through menopause. This is because your body’s hormones and menstrual cycles change. Other risk factors for endometrial hyperplasia are:

- Long-term use of medicines that contain high levels of estrogen or chemicals that act like estrogen.

- Irregular menstrual cycles, which can be caused by infertility or polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

- Obesity.

- Use of tobacco.

- First menstrual cycle at an early age.

- Going through menopause at an older age.

- Never having been pregnant.

- Family history of uterine, ovarian, or colon cancer.

Endometrial hyperplasia pathology outlines

Endometrial hyperplasia is defined as a proliferation of endometrial glands of irregular size and shape that results in a greater than normal gland-to-stroma ratio 4. This results in varying degrees of architectural complexity and cytologic atypia.

Endometrial hyperplasia results from continuous estrogen stimulation that is unopposed by progesterone 28. This can be due to endogenous estrogen or exogenous estrogenic sources. Endogenous estrogen may be caused by chronic anovulation associated with polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Obesity also contributes to unopposed estrogen exposure due to chronic high levels of estradiol that result from aromatization of androgens in adipose tissue and conversion of androstenedione to estrone. Endometrial hyperplasia and cancer can also result from estradiol-secreting ovarian tumors such as granulosa cell tumors.

Exogenous unopposed estrogen without progesterone has been associated with increased endometrial hyperplasia and adenocarcinoma 29. The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) trial found that unopposed estrogen exposure with 0.625 mg of conjugated equine estrogen replacement therapy increased the risk of complex hyperplasia by 22.7% and atypical hyperplasia by 11.8% over 3 years of use compared with a less than 1% increase in placebo controls 30. The risk of endometrial cancer was not increased when 2.5 mg of medroxyprogesterone acetate was used in combination with 0.625 mg of conjugated equine estrogens in 8506 women in the Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) study 31. Tamoxifen, with its estrogenic effect on the endometrium, increases the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer. The risk of progression to cancer is associated with an increased duration of use 32. While unopposed estrogen in oral contraceptive pills or estrogen replacement therapy increases the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer, combination oral contraceptive pills and combination hormone replacement therapy does not increase and may decrease the risk of endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer 28.

However, the exact mechanism of estrogen’s role in the transformation of normal endometrium to hyperplasia and cancer is unknown 28. Genetic alterations are known to be associated with hyperplasia and type 1 endometrial cancers. Benign endometrial hyperplasia is associated with low levels of somatic mutations, whereas EIN is associated with genetic alternations similar to endometrioid endometrial cancer such as microsatellite instability, and mutations in PTEN and KRAS 33. PTEN tumor suppressor gene mutations have also been found in 55% of endometrial hyperplasia cases and 83% of endometrial hyperplasia cases once it has progressed to endometrial cancer 34.

Endometrial hyperplasia risk factors

Endometrial hyperplasia is more likely to occur in women with risk factors, including 6:

- Age (age older than 53 years)

- Early age when menstruation started (early menarche [a girl’s first period])

- Late menopause (older age at menopause)

- Nulliparity (a woman who hasn’t given birth to a child or never having been pregnant)

- Obesity: body mass index (BMI) of 27 or more

- Genetic

- Cigarette smoking

- History of certain conditions, such as diabetes mellitus, gallbladder disease, or thyroid disease.

- Anovulatory cycles: polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), perimenopause

- Ovarian tumors: granulosa cell tumors

- Hormone replacement therapy: estrogen-only therapy can lead to endometrial hyperplasia at even a minimal dose and is contraindicated in women with a uterus. Over the counter/ herbal preparations may have a high amount of estrogen 35

- Immunosuppression (renal graft recipients) and infection may also be involved in the development of endometrial hyperplasia 36

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) or Lynch syndrome – women with this condition are at a greatly increased risk of endometrial hyperplasia 37.

- Family history of ovarian, colon, or uterine cancer

The independent risk factors for predicting when endometrial hyperplasia coexists with cancer include age older than 53 years, postmenopausal status, diabetes, abnormal bleeding, body mass index (BMI) of 27 or more, and atypical hyperplasia 11.

Endometrial hyperplasia prevention

You cannot prevent endometrial hyperplasia, but you can help lower your risk of endometrial hyperplasia by:

- Losing weight, if you are overweight or obese.

- Quit smoking if you smoke cigarette

- Taking a medicine with progestin (synthetic progesterone), if you already are taking estrogen, due to menopause or another condition.

- If your periods are irregular, birth control pills may be recommended. They contain estrogen along with progestin. Other forms of progestin also may be taken.

- Taking birth control or another medicine to regulate your hormones and menstrual cycle.

Endometrial hyperplasia differential diagnosis

The potential differential diagnosis for endometrial hyperplasia are conditions which can result in focal or generalized thickening of the endometrium 5:

- Endometrial cancer: Histopathological examination of the endometrial tissue can show markers of invasions in endometrial cancer.

- Endometrial polyp: Hydrosonography can be helpful in diagnosing endometrial polyp by enhancing visualization. Diagnostic hysteroscopy can confirm the presence of a polyp.

- Endometritis: Irregular endometrium and focal thickness are the hallmarks of endometritis.

Endometrial hyperplasia diagnosis

There are many causes of abnormal uterine bleeding. If you have abnormal bleeding and you are 35 or older, or if you are younger than 35 and your abnormal bleeding has not been helped by medication, your doctor may recommend diagnostic tests for endometrial hyperplasia and cancer.

A transvaginal ultrasound exam may be done to measure the thickness of the endometrium. For this test, a small device is placed in your vagina. Sound waves from the device are converted into images of the pelvic organs. If the endometrium is thick, it may mean that endometrial hyperplasia is present.

The only way to tell for certain that cancer is present is to take a small sample of tissue from the endometrium and study it under a microscope. This can be done with an endometrial biopsy, dilation and curettage (D&C), or hysteroscopy.

Endometrial hyperplasia ultrasound

Imaging the endometrium on days 5-10 of a woman’s cycle reduces the variability in endometrial thickness 38.

- Premenopausal endometrial thickness

- Normal endometrial thickness depends on the stage of the menstrual cycle, but a thickness of >15 mm is considered the upper limit of normal in the secretory phase

- Endometrial hyperplasia can be reliably excluded in patients only when the endometrium measures less than 8 mm 39

- Postmenopausal endometrial thickness of >5 mm is considered abnormal 38.

The appearance can be non-specific and cannot reliably allow differentiation between endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial carcinoma 40. Usually, there is a homogeneous smooth increase in endometrial thickness, but endometrial hyperplasia may also cause asymmetric/focal thickening with surface irregularity, an appearance that is suspicious for carcinoma. Cystic changes can also be seen in endometrial hyperplasia.

Ultrasound features that are suggestive of endometrial carcinoma as opposed to endometrial hyperplasia include 41:

- heterogeneous and irregular endometrial thickening

- polypoid mass lesion

- intrauterine fluid collection

- frank myometrial invasion

Endometrial hyperplasia biopsy

Diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia is usually made by sampling the endometrial cavity with an endometrial biopsy in the office. Tissue sampling should be performed in women with risk factors who present with symptoms of abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge 42. This includes women older than 35 years with abnormal bleeding, women younger than 35 years with bleeding and risk factors, women with persistent bleeding, and women with unopposed estrogen replacement, tamoxifen therapy, and hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome or Lynch syndrome.

In addition, a biopsy should be performed in women with atypical glandular cells Pap smear or endometrial cells in Pap smears of women older than 40 years when out of synch with menstrual cycle 43. While no evidence of improved survival has been documented, some also advocate routine screening by endometrial biopsy in asymptomatic women with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome or those on tamoxifen therapy. However, most of this high-risk population present with abnormal vaginal bleeding; thus, other experts recommend work-up only when symptoms are present.

If a patient does not tolerate an office biopsy or has cervical stenosis, endovaginal ultrasonography is an effective method to assess thickness of the endometrial echo complex and to evaluate uterine bleeding. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends transvaginal ultrasonography as a reasonable alternative to endometrial sampling for the evaluation of an initial episode of bleeding in a postmenopausal woman 44.

Endovaginal ultrasonography has a sensitivity of greater than 96% for ruling out endometrial carcinoma if the endometrial echo complex is less than 5 mm. Persistent bleeding despite a thin stripe still warrants tissue biopsy because of the risk of missing a type 2 cancer that is not associated with hyperplasia and thickening of the endometrial echo complex 45. If hyperplasia is diagnosed by office biopsy, one should consider D&C and hysteroscopy to more definitely rule out atypia or cancer prior to conservative medical management. This is because blind dilation and curettage (D&C) and Pipelle endometrial biopsies both sample only 50-60% of the endometrial cavity, and can miss focal lesions 46.

Endometrial hyperplasia treatment

The accurate diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia type is vital for appropriate treatment based on risk of cancer without over or under treatment 47. Once a tissue diagnosis of endometrial hyperplasia is made, treatment depends on the type of hyperplasia, the patient’s symptoms such as severity of bleeding, surgical risks, and wish for future childbearing.

In many cases, endometrial hyperplasia can be treated with progestin (man made progesterone). Progesterone induce secretory changes in the endometrium and counterbalance the stimulatory effects of estrogen. Progestins can effectively treat endometrial hyperplasia to control bleeding and prevent progression to cancer. They can serve as prevention of recurrence in those with continued risk factors 47. Progestin is given orally, in a shot, in an intrauterine device (IUD), or as a vaginal cream. How much and how long you take it depends on your age and the type of endometrial hyperplasia you have. Treatment with progestin may cause vaginal bleeding like a period.

Multiple regimens of progestin therapy have been found effective in reversing endometrial hyperplasia, including the following 23.:

- Medroxyprogesterone acetate – MPA (Provera), 10-20 mg once daily or cyclic 12-14 days per month

- Depot Medroxyprogesterone (Depo-provera) 150 mg IM every 3 months

- Micronized vaginal progesterone (Prometrium), 100-200 mg once daily or cyclic 12-14 days per month

- Levonorgestrel-containing IUD (Mirena), 20 mcg/day 48

- Megestrol acetate (Megace), 40-200 mg per day, usually reserved for women with atypical hyperplasia

Benign endometrial hyperplasia responds well to progestins. More than 98% of women with endometrial hyperplasia treated with cyclic progestins experienced regression of the disease in 3-6 months 49. However, if you have endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) or atypical endometrial hyperplasia changes in the lining of your uterus, the risk of endometrial cancer is increased by 42% 15. Hysterectomy may be a treatment option if you do not want another pregnancy. Talk with your doctor about the right treatment for you.

Interest is increasing in the use of levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) as a treatment option for endometrial hyperplasia to deliver local effect with less systemic side-effects 50. A 15-year study using the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) for 34 patients with endometrial hyperplasia found regression to atrophic endometrium in 94% 51. However, this study had only 4 (12%) patients with atypical hyperplasia 51. A meta-analysis of 24 observational studies, including 1,001 cases, indicate that progestins appeared to induce a lower disease regression rate than levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) in the treatment of complex and atypical endometrial hyperplasia. However, a controlled clinical trial is necessary to confirm the observational findings. The authors feel data using the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) as the only treatment modality for atypical hyperplasia or endometrial cancer are still limited 52.

The Postmenopausal Estrogen/Progestin Interventions (PEPI) trial showed a 94% normalization of complex or atypical hyperplasia in 45 women treated with progestins 30. One cohort study found that 115 patients with complex atypical hyperplasia had approximately 30% persistence or progression of disease whether treated with progestins or not. However, of 70 patients with atypical hyperplasia, 67% vs 27% had persistence or progression when not treated with progestins 53.

If the patient has not completed childbearing or is not a surgical candidate, then concurrent cancer must first be ruled out by D&C with hysteroscopy prior to medical management. Experts recommend megestrol acetate for endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN), with or without levonorgestrel IUD (intrauterine device) for patients wishing to preserve fertility or for those too ill for surgical management. Any progestin should be adequate for treatment of benign hyperplasia or for maintenance after resolution of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN). Patient should be sampled to assess for response every 3 to 6 months for regression to normal endometrium. If there is inadequate response in 6 months, consider increasing dose or changing progestins. There is no proven protocol for selection or dosing. Continued surveillance after regression of the lesion is recommended every 6 to 12 months if risk factors persist. Repeat biopsy is also indicated for recurrent abnormal bleeding or discharge. Prevention of recurrence include use of daily or cyclic progesterone, indwelling levonorgestrel IUD, along with weight loss for obese patients.

Due to the large number of young anovulatory women diagnosed with atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) or early endometrial cancer, numerous studies have examined the outcome of fertility-sparing hormonal therapy. A meta-analysis of 24 observational studies that included a total of 151 women with atypical endometrial hyperplasia found that those who had fertility-sparing treatments had 86% regression, 26% relapse, and live birth rate of 26% 54.

Another review of complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) patients who underwent progestin therapy found a complete response rate of 66% 55. Median time to response was 6 months. Recurrence rate after initial response was 23%. During study follow-up time of 39 months, 41% of patients with atypical hyperplasia became pregnant 55.

The Gynecologic Oncology Group pathologic study with biopsy diagnosis of atypical hyperplasia found 42.6% concurrent endometrial carcinoma on hysterectomy specimen; 31% of these had myometrial invasion, including 10.6% with outer half myometrial invasion 15. Others also found atypical endometrial hyperplasia on office biopsy or D&C was associated with a 48-56% cancer rate on permanent pathology. Thus, if a hysterectomy is planned for treatment of atypical hyperplasia based on office endometrial biopsy, the authors recommend having a gynecologic oncologist be primary surgeon, or be available for surgical staging if needed based on frozen section of uterine specimen 56, 46. Patients should be counseled and consented for washings, hysterectomy, possible bilateral-salpingo-oophorectomy and lymph node dissection depending on intra-op exam or frozen pathology findings. If a D&C with hysteroscopy had been performed to rule out concurrent carcinoma more definitively, an oncologic surgeon is likely not needed. Due to the risk of cancer, supracervical, morcellation, or endometrial ablation is not recommended. While a simple hysterectomy is adequate for definitive treatment of hyperplasia, one can consider bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy in perimenopausal or postmenopausal women due to possibility of cancer on permanent section. Ovaries should only be removed if cancer is diagnosed in premenopausal women. They should be counseled a second surgery may be required to remove ovaries and perform lymph node staging if cancer if found on final pathology.

The need for hysterectomy to exclude concurrent myoinvasive endometrioid adenocarcinoma presents a barrier to nonsurgical management of endometrial hyperplasia. A Gynecologic Oncology Group study examined the histomorphometric 4-class rule (4C), which measures epithelial abundance, thickness, and nuclear variation as applied to diagnostic biopsies to predict myoinvasive cancer outcomes at hysterectomy 57. Women with endometrial biopsies or curettages with a community diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia were enrolled in a clinical trial in which subsequent hysterectomy was scored for endometrial adenocarcinoma, and 4C rule ability to predict cancer outcomes was measured. Qualifying biopsies were stratified into high-risk and low-risk histomorphometric subgroups 57. Assignment to a high-risk category by 4C rule was highly sensitive in predicting any (71%) or deeply (92%) myoinvasive adenocarcinoma at hysterectomy, and assignment to a low-risk group had a high negative predictive value for absence of any (90%) or deeply (99%) myoinvasive disease 57. At present, this use of histomorphometry is most suited to a centralized reference laboratory performing histomorphometry for a variety of diagnostic applications. However, in the future, formal histomorphometry of endometrial biopsies using the 4C rule may become a more common method to identify a subset of women with premalignant disease who are unlikely to have concurrent myoinvasive adenocarcinoma and therefore may qualify for nonsurgical therapy.

Endometrial hyperplasia prognosis

Several studies have shown that progestogen (synthetic forms of progesterone) therapy leads to a high rate of regression in endometrial hyperplasia without atypia (89% to 96%) 52, 48, 49. However, in the presence of endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN), there is a reduction in the success rate of progestogen therapy 15. The presence of atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) has a higher risk of progression to invasive malignancy – as high as 27.5% if not treated 58. Also, atypical endometrial hyperplasia or endometrial intraepithelial neoplasia (EIN) has a possibility of coexistent endometrial malignancy in 43% of cases 15.

Endometrial cancer types

Endometrial cancer also called endometrial carcinoma, starts in the cells of the inner lining of the uterus (the endometrium). This is the most common type of cancer in the uterus 59.

Endometrial carcinomas can be divided into different types based on how the cells look under the microscope. These are called histologic types. They include:

- Adenocarcinoma (most endometrial cancers are a type of adenocarcinoma called endometrioid cancer or endometrial adenocarcinoma)

- Uterine carcinosarcoma

- Squamous cell carcinoma

- Small cell carcinoma

- Transitional carcinoma

- Serous carcinoma

Clear-cell carcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, dedifferentiated carcinoma, and serous adenocarcinoma are less common types of endometrial adenocarcinomas. They tend to grow and spread faster than most types of endometrial cancer. They often have spread outside the uterus by the time they’re diagnosed.

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma also called endometrial adenocarcinoma or endometrioid cancer, is the most common type of adenocarcinoma, by far. Endometrioid cancers start in gland cells and look a lot like the normal uterine lining (endometrium). Some of these cancers have squamous cells (squamous cells are flat, thin cells), as well as glandular cells.

There are many variants (or sub-types) of endometrioid cancers including:

- Adenocarcinoma, (with squamous differentiation)

- Adenoacanthoma

- Adenosquamous (or mixed cell)

- Secretory carcinoma

- Ciliated carcinoma

- Villoglandular adenocarcinoma

Endometrioid cancers are often diagnosed at an early stage and so are usually treated successfully.

Uterine carcinosarcoma

Uterine carcinosarcoma tumors are also known as malignant mixed mesodermal tumors or malignant mixed mullerian tumors. They make up about 3% of uterine cancers. Uterine carcinosarcoma starts in the endometrium and has features of both endometrial carcinoma and sarcoma. Sarcoma is cancer that starts in muscle cells of the uterus. In the past, uterine carcinosarcoma was considered a different type of uterine cancer called uterine sarcoma, but doctors now believe that uterine carcinosarcoma is an endometrial carcinoma that’s so abnormal it no longer looks much like the cells it came from (it’s poorly differentiated).

Uterine carcinosarcoma is a type 2 endometrial carcinoma.

Uterine sarcoma

Uterine sarcomas start in the muscle layer (myometrium) or supporting connective tissue of the uterus (the serosa or perimterium). Uterine sarcomas are a type of soft tissue sarcoma and are much less common than endometrial cancer. These include uterine leiomyosarcomas and endometrial stromal sarcomas. Leiomyosarcoma is the most common sarcoma of the womb. It is a cancer of the muscle wall. The treatment you need for this type of uterine cancer is not the same as other types of uterine cancer.

Most uterine sarcomas are put into categories, based on the type of cell they start in:

- Uterine leiomyosarcoma: These tumors start in the muscular wall of the uterus (the myometrium). They are by far the most common type. These tumors can grow and spread quickly.

- Endometrial stromal sarcoma: Endometrial stromal sarcoma tumors start in the supporting connective tissue (stroma) of the lining of the uterus (the endometrium). These cancers are rare.

- If the tumor is low grade, the cancer cells do not look very different from normal cells and the tumor tends to grow slowly. Women with low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma have a better outlook (prognosis) than women with other kinds of uterine sarcomas.

- High-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma means the cancer cells look very different from normal cells, and the tumor is growing quickly. This type of endometrial stromal sarcoma is most often found when the tumor is already large and/or has spread. These tumors are hard to treat.

- Undifferentiated sarcoma: These cancers may start in the endometrium or the myometrium. They grow and spread quickly and tend to have a poor outlook.

Type 1 and type 2 endometrial cancer

Doctors sometimes divide endometrial cancers into 2 types 60.

- Type 1 endometrial cancers are the most common type representing more than 70% of cases. They are usually endometrioid adenocarcinomas and are associated with unopposed estrogen stimulation or due to excess estrogen in the body. They are generally low grade, slow growing and less likely to spread 61.

- Type 2 endometrial cancers are not linked to excess estrogen. Type 2 endometrial cancer accounts for only 10% of endometrial cancers, but it is associated with 40% of related deaths 61. Type 2 tumors are more likely to be high grade and of papillary serous or clear cell histologic type. They are generally faster growing, carry a poor prognosis and have a high risk of relapse and more likely to spread. They include uterine serous carcinomas and clear cell carcinomas.

Endometrial cancer grades

The grade of an endometrial cancer is based on how much the cancer cells are organized into glands that look like the glands found in a normal, healthy endometrium. The grade of an endometrial cancer gives your doctor an idea of how quickly or slowly the cancer might grow and whether it is likely to spread. In lower-grade cancers (grades 1 and 2), more of the cancer cells form glands. In higher-grade cancers (grade 3), more of the cancer cells are disorganized and do not form glands.

Grading is a way of dividing cancer cells into groups depending on how much the cells look like normal cells.

- Grade 1 endometrial cancers also called low grade or well differentiated, have 95% or more of the cancer tissue forming glands. They tend to be slow growing and are less likely to spread than higher grade cancer cells.

- Grade 2 endometrial cancers also called moderately differentiated or moderate grade, have between 50% and 94% of the cancer tissue forming glands.

- Grade 3 endometrial cancers also called poorly differentiated or high grade, have less than half of the cancer tissue forming glands. Grade 3 cancers tend to be aggressive (they grow and spread fast) and have a worse outlook than lower-grade cancers.

Grades 1 and 2 endometrioid cancers are type 1 endometrial cancers. Type 1 cancers are usually not very aggressive and they don’t spread to other tissues quickly. Type 1 endometrial cancers are thought to be caused by too much estrogen. They sometimes develop from atypical hyperplasia, an abnormal overgrowth of cells in the endometrium.

A small number of endometrial cancers are type 2 endometrial cancer. Type 2 cancers are more likely to grow and spread outside the uterus, they have a poorer outlook (than type 1 cancers). Doctors tend to treat these cancers more aggressively. They don’t seem to be caused by too much estrogen. Type 2 cancers include all endometrial carcinomas that aren’t type 1, such as papillary serous carcinoma, clear-cell carcinoma, undifferentiated carcinoma, and grade 3 endometrioid carcinoma. These cancers don’t look at all like normal endometrium and so are called poorly differentiated or high-grade.

Endometrial cancer causes

Scientists do not yet know exactly what causes most cases of endometrial cancer, but they do know there are risk factors, like obesity and hormone imbalance, that are strongly linked to endometrial cancer. A great deal of research is going on to learn more about endometrial cancer.

Scientists know that most endometrial cancer cells contain estrogen and/or progesterone receptors on their surfaces. Somehow, interaction of these receptors with their hormones leads to increased growth of the endometrium. This can mark the beginning of cancer. The increased growth can become more and more abnormal until it develops into a cancer.

As noted in the risk factors section below, many of the known endometrial cancer risk factors affect the balance between estrogen and progesterone in the body.

Scientists are learning more about changes (mutations) in the DNA of certain genes that occur when normal endometrial cells become cancerous. The mutation turns normal, healthy cells into abnormal cells. Healthy cells grow and multiply at a set rate, eventually dying at a set time. Abnormal cells grow and multiply out of control, and they don’t die at a set time. The accumulating abnormal cells form a mass (tumor). Cancer cells invade nearby tissues and can separate from an initial tumor to spread elsewhere in the body (metastasize).

Endometrial cancer risk factors

A risk factor is anything that affects your chance of getting a disease such as cancer. Different cancers have different risk factors. Some risk factors, like smoking, can be changed. Others, like a person’s age or family history, can’t be changed.

Although certain factors increase a woman’s risk for developing endometrial cancer, they do not always cause the disease. Many women with one or more risk factors never develop endometrial cancer.

Some women with endometrial cancer do not have any known risk factors. Even if a woman with endometrial cancer has one or more risk factors, there is no way to know which, if any, of these factors was responsible for her cancer.

Many factors affect the risk of developing endometrial cancer, including:

- Things that affect hormone levels, like taking estrogen after menopause, birth control pills, or tamoxifen; the number of menstrual cycles (over a lifetime), pregnancy, obesity, certain ovarian tumors, and polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

- Use of an intrauterine device (IUD)

- Never having been pregnant

- Age

- Obesity

- Diet and exercise

- Type 2 diabetes

- Family history (having close relatives with endometrial or colorectal cancer)

- Having been diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer in the past

- Having been diagnosed with endometrial hyperplasia in the past

- Treatment with radiation therapy to the pelvis to treat another cancer

Some of these, like pregnancy, birth control pills, and the use of an intrauterine device are linked to a lower risk of endometrial cancer, while many are linked to a higher risk. These factors and how they affect endometrial cancer risk are discussed in more detail below.

Changes in the balance of female hormones in the body

A woman’s hormone balance plays a part in the development of most endometrial cancers. Many of the risk factors for endometrial cancer affect estrogen levels. Before menopause, the ovaries are the major source of the 2 main types of female hormones — estrogen and progesterone. The balance between these hormones changes each month during a woman’s menstrual cycle. This produces a woman’s monthly periods and keeps the endometrium healthy. A shift in the balance of these hormones toward more estrogen increases a woman’s risk for endometrial cancer. A disease or condition that increases the amount of estrogen, but not the level of progesterone, in your body can increase your risk of endometrial cancer. Examples include irregular ovulation patterns, which might happen in polycystic ovary syndrome, obesity and diabetes. A rare type of ovarian tumor that secretes estrogen also can increase the risk of endometrial cancer.

After menopause, the ovaries stop making these hormones, but a small amount of estrogen is still made naturally in fat tissue. Estrogen from fat tissue has a bigger impact after menopause than it does before menopause. Also taking hormones after menopause that contain estrogen but not progesterone increases the risk of endometrial cancer.

Estrogen therapy

Treating the symptoms of menopause with hormones is known as menopausal hormone therapy (or sometimes hormone replacement therapy [HRT]). Estrogen is the major part of this treatment. Estrogen treatment can help reduce hot flashes, improve vaginal dryness, and help prevent the weakening of the bones (osteoporosis) that can occur with menopause.

But using estrogen alone (without progesterone) can lead to endometrial cancer in women who still have a uterus. To lower that risk, a progestin (progesterone or a drug like it) must be given along with estrogen. This is called combination hormone therapy.

Women who take progesterone along with estrogen to treat menopausal symptoms do not have an increased risk of endometrial cancer. Still, taking this combination increases a woman’s chance of developing breast cancer and also increases the risk of serious blood clots.

If you are taking (or plan to take) hormones after menopause, it’s important to discuss the possible risks (including cancer, blood clots, heart attacks, and stroke) with your doctor.

Like any other medicine, hormones should be used at the lowest dose needed and for the shortest possible time to control symptoms. As with any other medicine you take for a long time, you’ll need to see your doctor regularly. Experts recommend yearly follow-up pelvic exams. If you have any abnormal bleeding or discharge from your vagina you should see a health care provider right away. Do not wait until your next check-up.

Birth control pills

Using birth control pills (oral contraceptives) lowers the risk of endometrial cancer. The risk is lowest in women who take the pill for a long time, and this protection lasts for at least 10 years after a woman stops taking the pill. But it’s important to look at all of the risks and benefits when choosing a contraceptive method; endometrial cancer risk is only one factor to consider. It’s a good idea to discuss the pros and cons of different types of birth control with your doctor.

Total number of menstrual cycles

Having more menstrual cycles during a woman’s lifetime raises her risk of endometrial cancer. Starting first menstrual periods (menarche) before age 12 and/or going through menopause later in life raises the risk. Starting periods early is less a risk factor for women with early menopause. Likewise, late menopause may not lead to a higher risk in women whose periods began later in their teens.

Never having been pregnant

The hormonal balance shifts toward more progesterone during pregnancy. So having many pregnancies helps protect against endometrial cancer. Women who have never been pregnant have a higher risk, especially if they were also infertile (unable to become pregnant).

Obesity

Obesity is a strong risk factor for endometrial cancer and linked to hormone changes. A woman’s ovaries produce most of her estrogen before menopause. But fat tissue can change some other hormones (called androgens) into estrogens. This can impact estrogen levels, especially after menopause. Having more fat tissue can increase a woman’s estrogen levels, which increases her endometrial cancer risk.

In comparison with women who stay at a healthy weight, endometrial cancer is twice as common in overweight women (BMI 25 to 29.9), and more than 3 times as common in obese women (BMI > 30).

Gaining weight as you get older age and weight cycling (gaining and losing a lot of weight many times in your life) have also been linked to a higher risk of endometrial cancer after menopause.

Tamoxifen

Tamoxifen is a drug that is used to help prevent and treat breast cancer. Tamoxifen acts as an anti-estrogen in breast tissue, but it acts like an estrogen in the uterus. In women who have gone through menopause, it can cause the uterine lining to grow, which increases the risk of endometrial cancer.

The risk of developing endometrial cancer from tamoxifen is low (less than 1% per year). Women taking tamoxifen must balance this risk against the benefits of this drug in treating and preventing breast cancer. This is an issue women should discuss with their providers. If you are taking tamoxifen, you should have yearly gynecologic exams and should be sure to report any abnormal bleeding, as this could be a sign of endometrial cancer.

Ovarian tumors

A certain type of ovarian tumor, the granulosa cell tumor, often makes estrogen. Estrogen made by one of these tumors isn’t controlled the way hormone release from the ovaries is, and it can sometimes lead to high estrogen levels. The resulting hormone imbalance can stimulate the endometrium and even lead to endometrial cancer. In fact, sometimes vaginal bleeding from endometrial cancer is the first symptom of one of these tumors.

Polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS)

Women with a condition called polycystic ovarian syndrome (PCOS) have abnormal hormone levels, such as higher androgen (male hormones) and estrogen levels and lower levels of progesterone. The increase in estrogen relative to progesterone can increase a woman’s chance of getting endometrial cancer. PCOS is also a leading cause of infertility in women.

Using an intrauterine device (IUD)

Women who used an intrauterine device (IUD) for birth control seem to have a lower risk of getting endometrial cancer. Information about this protective effect is limited to IUDs that do not contain hormones. Researchers have not yet studied whether newer types of IUDs that release progesterone have any effect on endometrial cancer risk. But these IUDs are sometimes used to treat pre-cancers and early endometrial cancers in women who wish to be able to get pregnant in the future.

Age

As you get older, your risk of endometrial cancer increases. Endometrial cancer occurs most often after menopause.

Diet and exercise

A high-fat diet can increase the risk of many cancers, including endometrial cancer. Because fatty foods are also high-calorie foods, a high-fat diet can lead to obesity, which is a well-known endometrial cancer risk factor. Many scientists think this is the main way in which a high-fat diet raises endometrial cancer risk. Some scientists think that fatty foods may also have a direct effect on how the body uses estrogen, which increases endometrial cancer risk.

Physical activity lowers the risk of endometrial cancer. Many studies have found that women who exercise more have a lower risk of endometrial cancer, while others suggest that women who spent more time sitting have a higher risk.

Diabetes

Endometrial cancer may be about twice as common in women with type 2 diabetes. But diabetes is more common in people who are overweight and less active, which are also risk factors for endometrial cancer. This makes it hard to find a clear link.

Family history

Endometrial cancer tends to run in some families. Some of these families also have a higher risk for colon cancer. This disorder is called hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC) or Lynch syndrome. In most cases, hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC) is caused by a defect in either the mismatch repair gene MLH1 or the gene MSH2. But at least 5 other genes can cause HNPCC: MLH3, MSH6, TGBR2, PMS1, and PMS2. An abnormal copy of any one of these genes reduces the body’s ability to repair damage to its DNA or control cell growth. This results in a very high risk of colon cancer, as well as a high risk of endometrial cancer. Women with this syndrome have a up to a 70% risk of developing endometrial cancer at some point. The risk for women in general is about 3%. The risk of ovarian cancer is also increased.

Some families have a higher rate of only endometrial cancer. These families may have a different genetic disorder that hasn’t been found yet.

Breast or ovarian cancer

Women who have had breast cancer or ovarian cancer may have an increased risk of endometrial cancer, too. Some of the dietary, hormone, and reproductive risk factors for breast and ovarian cancer also increase endometrial cancer risk.

Endometrial hyperplasia

Endometrial hyperplasia is an increased growth of the endometrium. Mild or simple hyperplasia, the most common type, has a very small risk of becoming cancer. It may go away on its own or after treatment with hormone therapy. If the hyperplasia is called “atypical,” it has a higher chance of becoming a cancer. Simple atypical hyperplasia turns into cancer in about 8% of cases if it’s not treated. Complex atypical hyperplasia has a risk of becoming cancer in up to 29% of cases if it’s not treated, and the risk of having an undetected endometrial cancer is even higher. For this reason, complex atypical hyperplasia is usually treated.

Prior pelvic radiation therapy

Radiation used to treat some other cancers can damage the DNA of cells, sometimes increasing the risk of a second type of cancer such as endometrial cancer.

Endometrial cancer prevention

Most cases of endometrial cancer cannot be prevented, but there are some things that may lower your risk of developing this disease.

To reduce your risk of endometrial cancer, you may wish to:

- Get to and stay at a healthy weight. One way to lower endometrial cancer risk is to do what you can to change your risk factors whenever possible. For example, women who are overweight or obese have up to 3½ times the risk of getting endometrial cancer compared with women at a healthy weight. Getting to and maintaining a healthy weight is one way to lower the risk of this cancer.

- Be physically active. Studies have also linked higher levels of physical activity to lower risks of endometrial cancer, so engaging in regular physical activity (exercise) may also be a way to help lower endometrial cancer risk. An active lifestyle can help you stay at a healthy weight, as well as lower the risk of high blood pressure and diabetes (other risk factors for endometrial cancer.

- Discuss pros and cons of hormone therapy with your doctor. Estrogen to treat the symptoms of menopause is available in many different forms like pills, skin patches, shots, creams, and vaginal rings. If you are thinking about using estrogen for menopausal symptoms, ask your doctor about how it will affect your risk of endometrial cancer. Progestins (progesterone-like drugs) can reduce the risk of endometrial cancer in women taking estrogen therapy, but this combination increases the risk of breast cancer. If you still have your uterus and are taking estrogen therapy, discuss this issue with your doctor.

- Consider taking birth control pills. Using oral contraceptives for at least one year may reduce endometrial cancer risk. The risk reduction is thought to last for several years after you stop taking oral contraceptives. Oral contraceptives have side effects, though, so discuss the benefits and risks with your doctor.

- Get treated for endometrial problems. Getting proper treatment of pre-cancerous disorders of the endometrium is another way to lower the risk of endometrial cancer. Most endometrial cancers develop over a period of years. Many are known to follow and possibly start from less serious abnormalities of the endometrium called endometrial hyperplasia. Some cases of hyperplasia will go away without treatment, but it sometimes needs to be treated with hormones or even surgery. Treatment with progestins and a dilation and curettage (D&C) or hysterectomy can prevent hyperplasia from becoming cancerous. Abnormal vaginal bleeding is the most common symptom of endometrial pre-cancers and cancers, and it needs to be reported and evaluated right away.

- Hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC). Women with hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer (HNPCC or Lynch syndrome) have a very high risk of endometrial cancer. Most experts recommend that a woman with HNPCC have her uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes removed (a hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy) after she’s finished having children to prevent endometrial cancer.

Endometrial cancer signs and symptoms

There are a few symptoms that may point to endometrial cancer, but some are more common as this cancer becomes advanced.

Unusual vaginal bleeding, spotting, or other discharge

About 90% of women diagnosed with endometrial cancer have abnormal vaginal bleeding, such as a change in their periods or bleeding between periods or after menopause. This symptom can also occur with some non-cancerous conditions, but it is important to have a doctor look into any irregular bleeding right away. If you have gone through menopause already, it’s especially important to report any vaginal bleeding, spotting, or abnormal discharge to your doctor.

Non-bloody vaginal discharge may also be a sign of endometrial cancer. Even if you cannot see blood in the discharge, it does not mean there is no cancer. In about 10% of cases, the discharge associated with endometrial cancer is not bloody. Any abnormal discharge should be checked out by your doctor.

Pelvic pain, a mass, and weight loss

Pain in the pelvis, feeling a mass (tumor), and losing weight without trying can also be symptoms of endometrial cancer. These symptoms are more common in later stages of the disease. Still, any delay in seeking medical help may allow the disease to progress even further. This lowers the odds of treatment being successful.

Although any of these symptoms can be caused by things other than cancer, it’s important to have them checked out by a doctor.

Can endometrial cancer be found early?

In most cases, noticing any signs and symptoms of endometrial cancer, such as abnormal vaginal bleeding or discharge (that is increasing in amount, occurring between periods, or occurring after menopause), and reporting them right away to your doctor allows the disease to be diagnosed at an early stage. Early detection improves the chances that your cancer will be treated successfully. But some endometrial cancers may reach an advanced stage before signs and symptoms can be noticed.

Early detection tests (Screening)

Early detection (also called screening) refers to the use of tests to find a disease such as cancer in people who do not have symptoms of that disease.

Women at average endometrial cancer risk

At this time, there are no screening tests or exams to find endometrial cancer early in women who are at average endometrial cancer risk and have no symptoms.

The American Cancer Society recommends that, at menopause, all women should be told about the risks and symptoms of endometrial cancer and strongly encouraged to report any vaginal bleeding, discharge, or spotting to their doctor.

Women should talk to their doctors about getting regular pelvic exams. A pelvic exam can find some cancers, including some advanced uterine cancers, but it is not very effective in finding early endometrial cancers.

The Pap test, which screens women for cervical cancer, can occasionally find some early endometrial cancers, but it’s not a good test for this type of cancer.

Women at increased endometrial cancer risk

The American Cancer Society recommends that most women at increased risk should be informed of their risk and be advised to see their doctor whenever they have any abnormal vaginal bleeding. This includes women whose risk of endometrial cancer is increased due to increasing age, late menopause, never giving birth, infertility, obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, estrogen treatment, or tamoxifen therapy.

Women who have (or may have) hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC, sometimes called Lynch syndrome) have a very high risk of endometrial cancer. If several family members have had colon or endometrial cancer, you might want to think about having genetic counseling to learn about your family’s risk of having HNPCC.

If you (or a close relative) have genetic testing and are found to have a mutation in one of the genes for HNPCC, you are at high risk of getting endometrial cancer.

The American Cancer Society recommends that women who have (or may have) HNPCC be offered yearly testing for endometrial cancer with endometrial biopsy beginning at age 35. Their doctors should discuss this test with them, including its risks, benefits, and limitations. This applies to women known to carry HNPCC-linked gene mutations, women who are likely to carry such a mutation (those with a mutation known to be present in the family), and women from families with a tendency to get colon cancer where genetic testing has not been done.

Another option for a woman who has (or may have) HNPCC would be to have a hysterectomy once she is done having children.

Endometrial cancer diagnosis

If you have any of the symptoms of endometrial cancer, you should see a doctor right away. Your doctor will ask you about your symptoms including what they are, when you get them and whether anything you do makes them better or worse. Your doctor will also do a physical exam and a pelvic exam.

Your doctor decide about whether to refer you for tests or to a specialist. If you are diagnosed with endometrial cancer you will have more tests to find out how big it is and whether it has spread. This is called staging.

Tests and procedures used to diagnose endometrial cancer include:

Pelvic examination

During a pelvic exam, your doctor carefully inspects the outer portion of your genitals (vulva), and then inserts two fingers of one hand into your vagina and simultaneously presses the other hand on your abdomen to feel your uterus and ovaries. He or she also inserts a device called a speculum into your vagina. The speculum opens your vagina so that your doctor can view your vagina and cervix for abnormalities.

Ultrasound

Ultrasound is often one of the first tests used to look at the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes in women with a possible gynecologic problem. Ultrasound tests use sound waves to take pictures of parts of the body. A small instrument called a transducer or probe gives off sound waves and picks up the echoes as they bounce off the organs. A computer translates the echoes into pictures.

For a pelvic ultrasound, the transducer is placed on the skin of the lower part of the abdomen. Often, to get good pictures of the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes, the bladder needs be full. That is why women getting a pelvic ultrasound are asked to drink lots of water before the exam.

A transvaginal ultrasound (TVUS) is often preferred for looking at the uterus. For this test, the TVUS probe (that works the same way as the ultrasound transducer) is put into the vagina. Images from the TVUS can be used to see if the uterus contains a mass (tumor), or if the endometrium is thicker than usual, which can be a sign of endometrial cancer. It may also help see if a cancer is growing into the muscle layer of the uterus (myometrium).

A small tube may be used to put salt water (saline) into the uterus before the ultrasound. This helps the doctor see the uterine lining more clearly. This procedure is called a saline infusion sonogram or hysterosonogram. Sonogram is another term for ultrasound.

Ultrasound can be used to see endometrial polyps (growths) , measure how thick the endometrium is, and can help doctors pinpoint the area they want to biopsy.

Endometrial tissue sampling

To find out exactly what kind of endometrial change is present, the doctor must take out some tissue so that it can be tested and looked at with a microscope. Endometrial tissue can be removed by endometrial biopsy or by dilation and curettage (D&C) with or without a hysteroscopy. A gynecologist usually does these procedures.

Endometrial biopsy

An endometrial biopsy is the most commonly performed test for endometrial cancer and is very accurate in postmenopausal women. It can be done in the doctor’s office. In this procedure a very thin flexible tube is inserted into the uterus through the cervix. Then, using suction, a small amount of endometrium is removed through the tube. The suctioning takes about a minute or less. The discomfort is similar to menstrual cramps and can be helped by taking a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug such as ibuprofen before the procedure. Sometimes numbing medicine (local anesthetic) is injected into the cervix just before the procedure to help reduce the pain.

Hysteroscopy

For this technique doctors insert a tiny telescope (about 1/6 inch in diameter) into the uterus through the cervix. To get a better view of the inside of the uterus, the uterus is filled with salt water (saline). This lets the doctor see and biopsy anything abnormal, such as a cancer or a polyp. This is usually done using a local anesthesia (numbing medicine) with the patient awake.

Dilation and curettage (D&C)

If the endometrial biopsy sample doesn’t provide enough tissue, or if the biopsy suggests cancer but the results are uncertain, a D&C must be done. In this outpatient procedure, the opening of the cervix is enlarged (dilated) and a special instrument is used to scrape tissue from inside the uterus. This may be done with or without a hysteroscopy.

This procedure takes about an hour and may require general anesthesia (where you are asleep) or conscious sedation (given medicine into a vein to make you drowsy) either with local anesthesia injected into the cervix or a spinal (or epidural). A D&C is usually done in an outpatient surgery area of a clinic or hospital. Most women have little discomfort after this procedure.

Testing endometrial tissue samples

Endometrial tissue samples removed by biopsy or D&C are looked at with a microscope to see whether cancer is present. If cancer is found, the lab report will state what type of endometrial cancer it is (like endometrioid or clear cell) and what grade it is.

Endometrial cancer is graded on a scale of 1 to 3 based on how much it looks like normal endometrium. Women with lower grade cancers are less likely to have advanced disease or recurrences.

Testing for gene and protein changes in the cancer cells

If the doctor suspects hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (HNPCC) as an underlying cause of the endometrial cancer, the tumor cells can be tested for protein and gene changes. Examples of HNPCC-related changes include:

- Having fewer mismatch repair (MMR) proteins

- Defects in mismatch repair genes (dMMR)

- DNA changes (high levels of microsatellite instability, or MSI-H) that can happen when one of the genes that causes HNPCC is faulty

If these protein or DNA changes are present, the doctor may suggest genetic testing for the genes that cause HNPCC.

Testing the cancer cells for dMMR, MSI-H, and/or a high tumor mutational burden (TMB-H) might also be done to see if treatment with immunotherapy might be an option, especially for more advanced endometrial cancers.

Tests to look for cancer spread

If the doctor suspects that your cancer is advanced, you will probably have to have other tests to look for cancer spread.

Chest x-ray

A plain x-ray of your chest may be done to see if cancer has spread to your lungs.

Computed tomography (CT)

The CT scan is an x-ray procedure that creates detailed, cross-sectional images of your body. For a CT scan, you lie on a table while an X-ray takes pictures. Instead of taking one picture, like a standard x-ray, a CT scanner takes many pictures as the camera rotates around you. A computer then combines these pictures into an image of a slice of your body. The machine will take pictures of many slices of the part of your body that is being studied.

CT scans are not used to diagnose endometrial cancer. However, they may be helpful to see whether the cancer has spread to other organs and to see if the cancer has come back after treatment.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

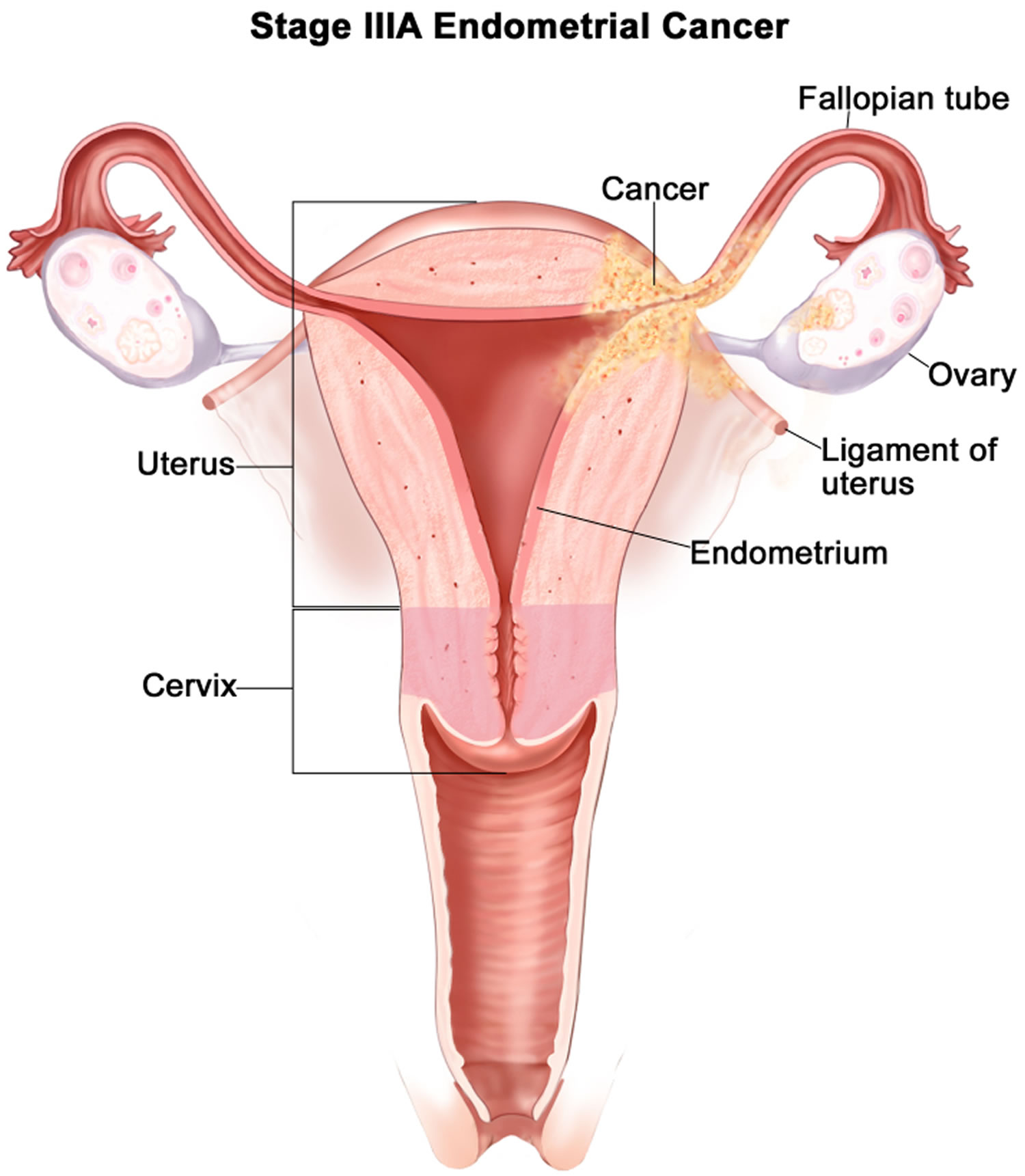

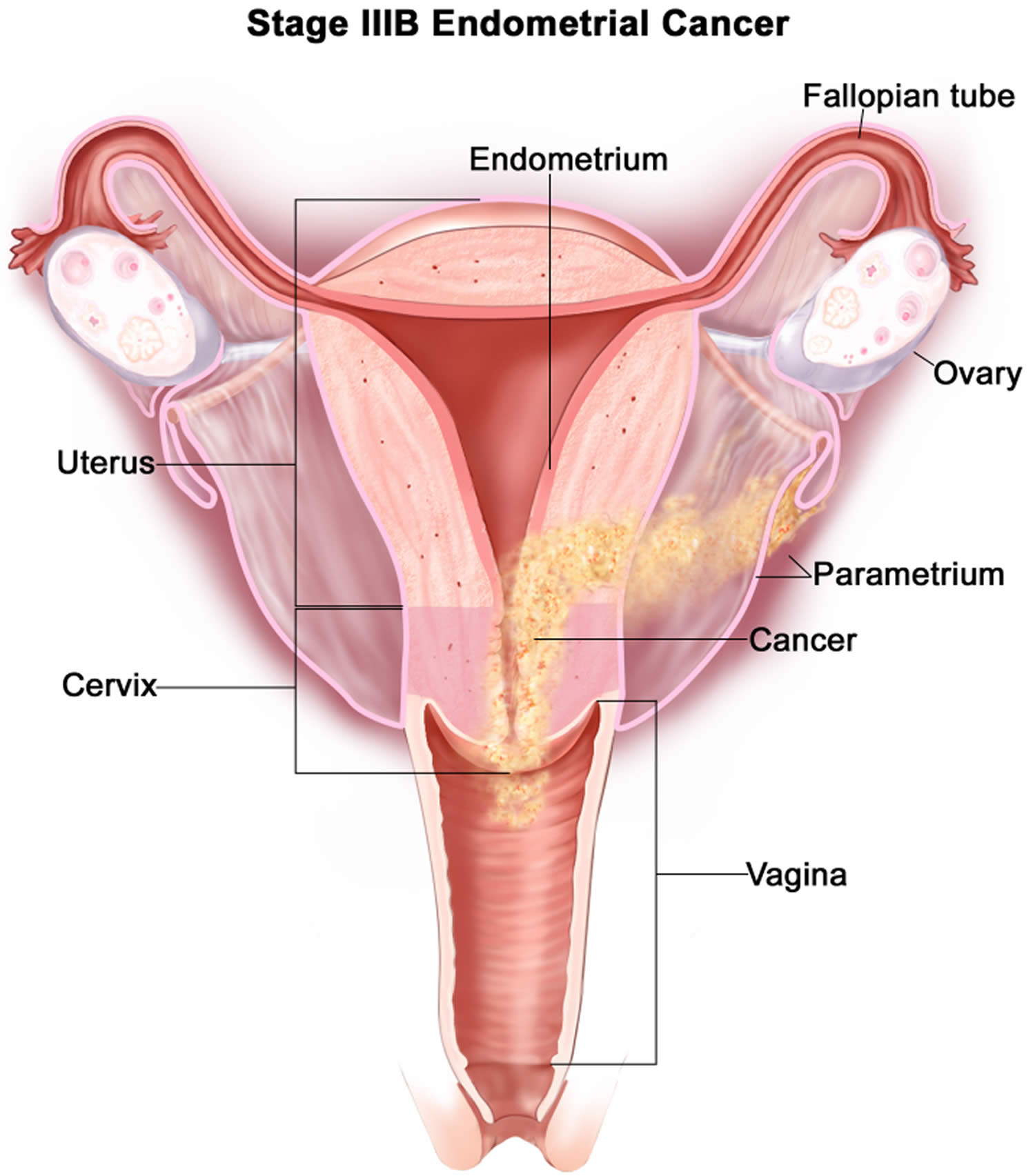

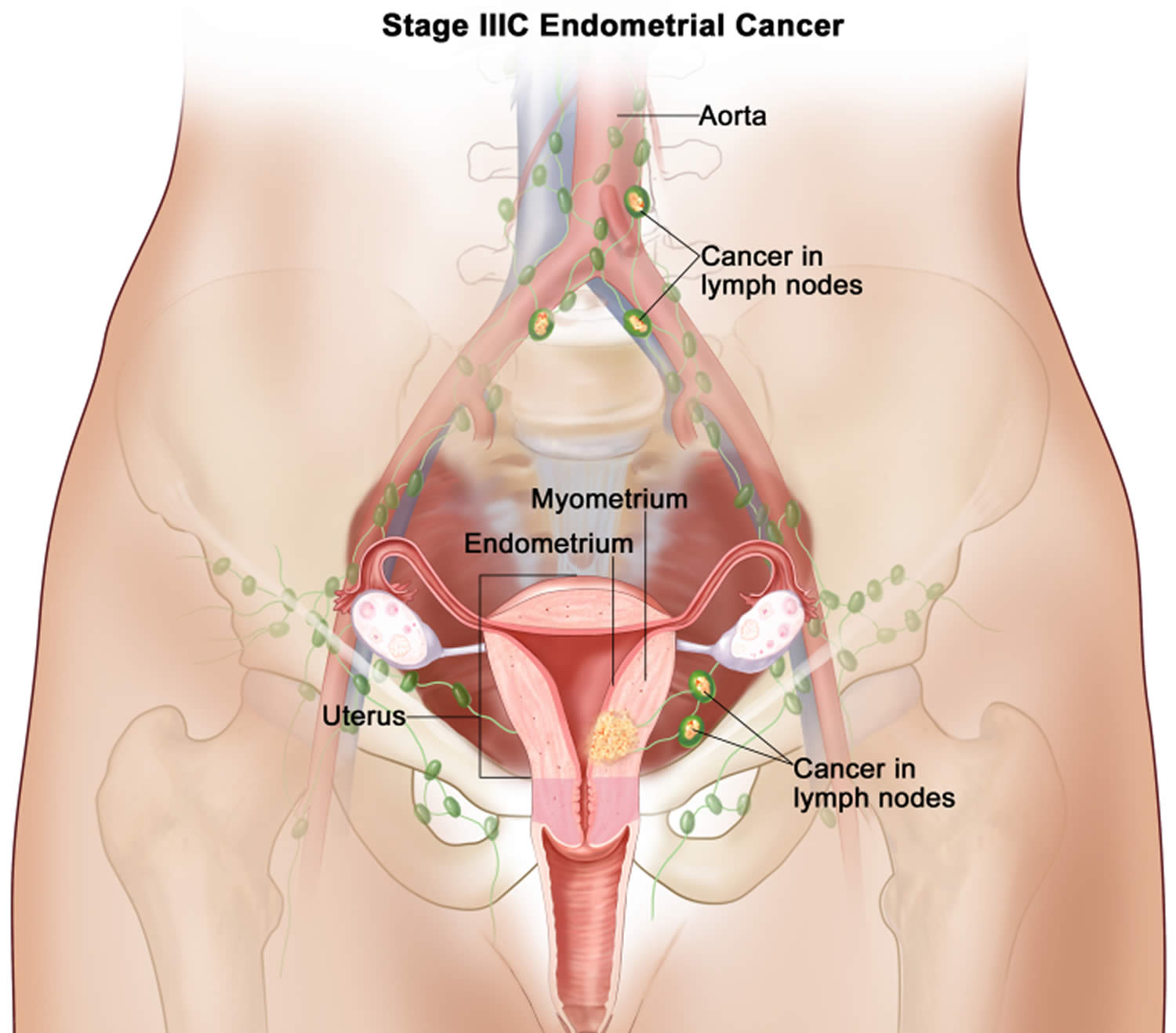

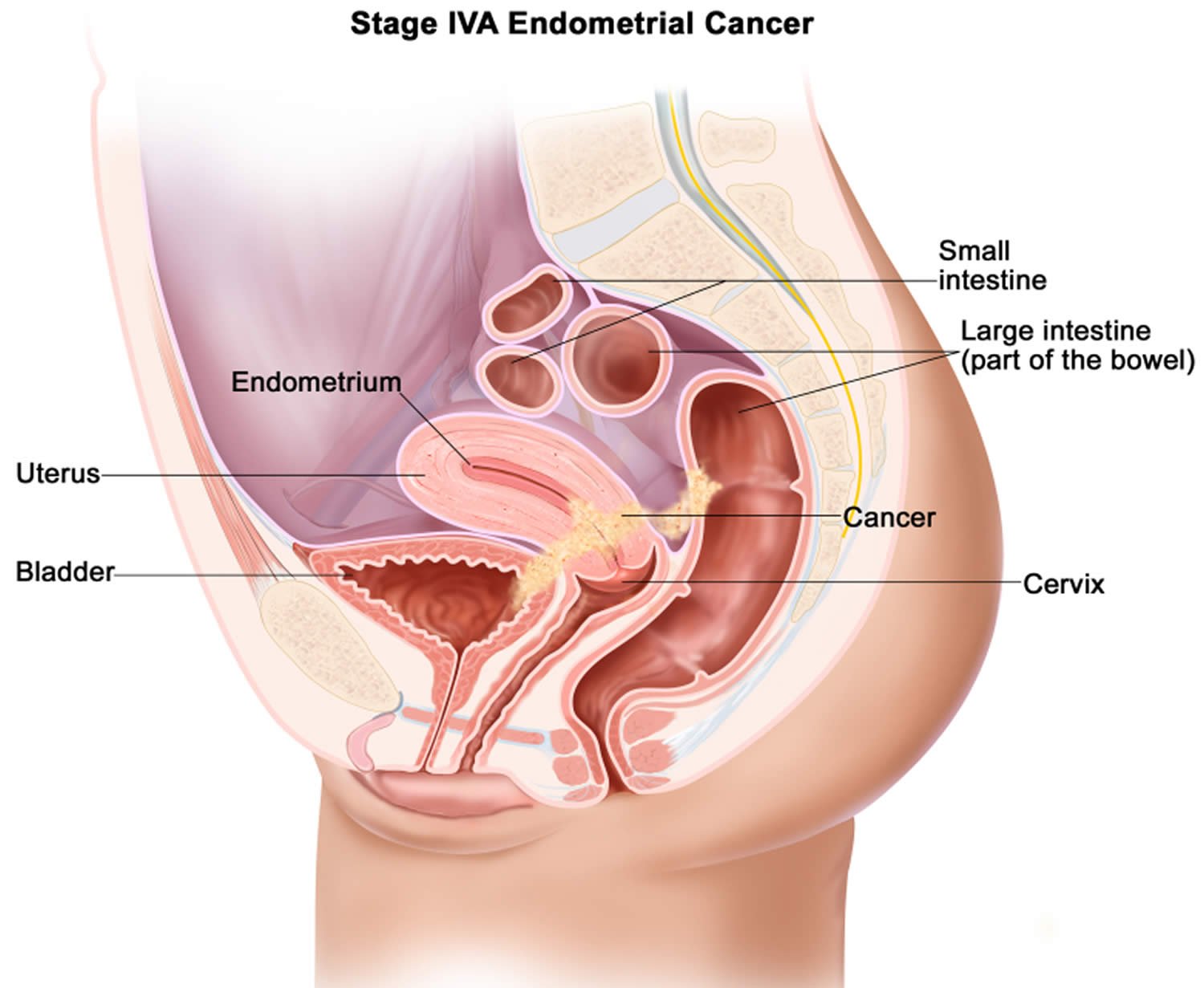

MRI scans use radio waves and strong magnets instead of x-rays. The energy from the radio waves is absorbed and then released in a pattern formed by the type of tissue and by certain diseases. A computer translates the pattern of radio waves given off by the tissues into a very detailed image of parts of the body. This creates cross sectional slices of the body like a CT scanner and it also produces slices that are parallel with the length of your body.