What is fatty liver disease

Fatty liver disease is a condition in which fat (triglycerides) builds up in your liver. Fatty liver or hepatic steatosis, is the accumulation of fat within liver cells, is a common histological finding in human liver biopsy specimens and affects 10–24% of the general population 1. There are two main types of fatty liver disease 2:

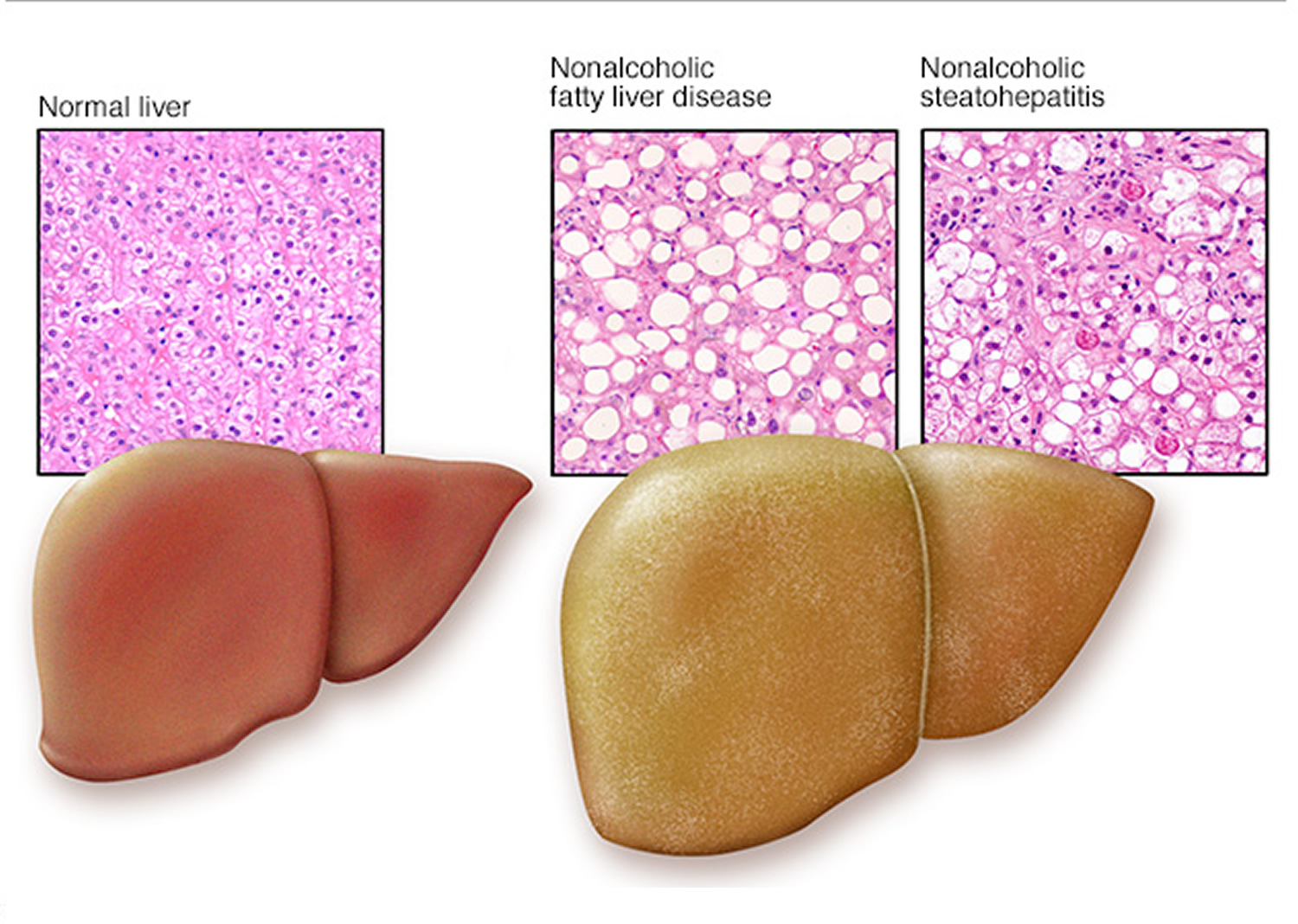

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is a type of fatty liver disease that is not related to heavy alcohol use. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common form of liver disease in the United States, affecting up to 30% of adults 3. There are two kinds of NAFLD 4:

- Simple fatty liver also called nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL): Simple fatty liver is a form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in which you have fat in your liver but little or no inflammation or liver cell damage. Simple fatty liver or nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) is defined as 5% or greater hepatic steatosis without hepatocellular injury or fibrosis 3. Simple fatty liver typically does not progress to cause liver damage or complications 5.

- Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH): Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in which you have inflammation and liver cell damage, in addition to fat in your liver. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is defined as 5% or greater hepatic steatosis plus hepatocellular injury and inflammation, with or without fibrosis 3. This form of liver injury carries a 20%-50% risk for progressive liver fibrosis, 30% risk for cirrhosis, and 5% risk for hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer) 6. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) may lead to cirrhosis or liver cancer 5.

- Alcoholic fatty liver disease also called alcoholic steatohepatitis. Alcoholic fatty liver disease (alcoholic steatohepatitis) is due to heavy alcohol use. Your liver breaks down most of the alcohol you drink, so it can be removed from your body. But the process of breaking it down can generate harmful substances. These substances can damage liver cells, promote inflammation, and weaken your body’s natural defenses. The more alcohol that you drink, the more you damage your liver. Alcoholic fatty liver disease is the earliest stage of alcohol-related liver disease. The next stages are alcoholic hepatitis and cirrhosis.

Your liver is the largest organ inside your body and it is a vital organ that performs many essential functions. Your liver filters out harmful substances from your blood, makes bile to digest food, stores energy and nutrients, and manufactures hormones, proteins, and enzymes your body uses to function, remove poisons and ward off disease 7.

The fatty liver may or may not be inflamed. Inflammation of the liver due to fatty liver is called steatohepatitis. This inflammation may develop into scarring (fibrosis). Fibrosis often progresses to cirrhosis (scarring that distorts the structure of the liver and impairs its function).

Fatty liver (with or without fibrosis) due to any condition except consumption of large amounts of alcohol is called nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). NAFLD develops most often in people with at least one of the components of metabolic syndrome:

- Excess body weight

- High fat levels in the blood (triglyceride and cholesterol)

- Insulin resistance

Inflammation of the liver due to NAFLD is called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). This inflammation may develop into scarring (fibrosis) and cirrhosis.

People with fatty liver may feel tired or have mild abdominal discomfort but otherwise have no symptoms. Sometimes fatty liver causes advanced liver disease such as fibrosis and cirrhosis.

A liver biopsy may be needed to confirm the diagnosis and to determine the cause and extent of the damage.

There are no medicines to treat fatty liver disease. Treatment of fatty liver focuses on controlling or eliminating the cause of fatty liver. Treatment involves making changes to your lifestyle. This can improve the condition and even reverse it. Doctors focus on controlling or eliminating the cause of fatty liver, such as metabolic syndrome or consumption of large amounts of alcohol.

Liver anatomy

Your liver is essential to your life. You cannot live without your liver. Your liver is the largest internal organ in your body. Your liver is about the size of a football and weighs about 3 to 3.5 pounds (1.36–1.59kg). Your liver lies under your right ribs just beneath your right lung. Your liver has two lobes (sections). Your liver is made up mainly of liver cells called hepatocytes. It also has other types of cells, including cells that line its blood vessels and cells that line small tubes in the liver called bile ducts. The bile ducts carry bile from the liver to the gallbladder or directly to the intestines.

Your liver has many important functions:

- It breaks down and stores many of the nutrients absorbed from the intestine that your body needs to function. Some nutrients must be changed (metabolized) in the liver before they can be used for energy or to build and repair body tissues.

- It makes most of the clotting factors that keep you from bleeding too much when you are cut or injured.

- It delivers bile into the intestines to help absorb nutrients (especially fats).

- It breaks down alcohol, drugs, and toxic wastes in the blood, which then pass from the body through urine and stool.

Figure 1. Liver anatomy

Fatty liver of pregnancy

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is considered the liver manifestation of the metabolic syndrome, and is tightly linked with obesity and type 2 diabetes 8. The obesity epidemic has affected reproductive-aged women, with obesity present in over one third of U.S. women ages 20–39 years 9. Pregnancy itself is a relative insulin resistant state and concurrent maternal obesity further increases the risk for gestational diabetes 10.

In the U.S., a study was conducted from 2012 to 2016 on a total of 18.5 million pregnant women 11. The aim was to find out how high certain pregnancy risks are in comparison groups 11. In the evaluation, a distinction was made between 3 groups of pregnant women. The first group consisted of women without liver disease. The second group had chronic liver disease (n = 115,210). The third group were women with NAFLD (n = 5,640). It was shown that pregnant women with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) have a higher risk of developing pregnancy-associated (gestational) diabetes compared to the control group (23 in 100 compared to 7-8 in 100) 11. It was also found that pregnant women with NAFLD are also more frequently affected by severe pregnancy-induced increases in blood pressure (16 out of 100 compared to 4 out of 100 if there was no liver disease), of which the HELLP (hemolysis-elevated liver tests-low platelet count) syndrome is the most severe complication. HELLP syndrome is a rare life-threatening condition during pregnancy, the course of which is difficult to predict. This leads to a breakdown of the red blood cells, increased liver enzymes and a drop in red blood platelets. HELLP syndrome can result in immediate termination of pregnancy.

Your gynaecologist should contact the doctor treating your fatty liver disease and make an assessment of your possible individual risks of pregnancy. You should be informed in detail. In addition, physicians should support you in reducing metabolic risk factors, such as the existence of fatty liver, during a planned pregnancy.

Fatty liver causes

Fat accumulates in the liver for several reasons. Most commonly, fatty liver involves increased delivery of free fatty acids to the liver, increased synthesis of fatty acids in the liver, decreased oxidation of free fatty acid, or decreased synthesis or secretion of very-low-density lipoprotein (VLDL) 12. Oxidative stress in the liver cells can activate stellate cells and lead to the production of collagen and inflammation 13.

The most common causes of fatty liver in the United States and other Western countries are 14:

- Consumption of large amounts of alcohol

- Obesity

- Type 2 diabetes and prediabetes

- Metabolic abnormalities, such as excess body weight, insulin resistance (as can occur in diabetes), and high levels of fats (triglycerides and cholesterol) in the blood

- Metabolic syndrome (insulin resistance, high blood pressure, high cholesterol and high triglyceride levels).

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

- Obstructive sleep apnea.

- Hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid).

- Hypopituitarism (low pituitary gland hormones).

- Hypogonadism (low sex hormones).

- Exposure to some toxins

- Certain drugs, including corticosteroids, amiodarone, diltiazem, tamoxifen, HIV treatment, estrogens, and certain chemotherapy drugs and others

- Hereditary metabolic disorders called lipodystrophies, that cause your body to use or store fat improperly

- Pregnancy

Other factors that may contribute to fatty liver disease include:

- The use of medications (e.g., tamoxifen, amiodarone, methotrexate)

- Metabolic disorders (e.g., metabolic syndrome, glycogen storage disorders, homocystinuria)

- Nutritional status (e.g., total parenteral nutrition, severe malnutrition, overnutrition, or a starvation diet)

- Rapid weight loss or malnutrition

- Rare genetic diseases like Wilson disease, celiac disease and hypobetalipoproteinemia

- Middle aged or older (although children can also get it)

- Hispanic, followed by non-Hispanic whites. It is less common in African Americans.

- High blood pressure

- Hepatitis C.

The combination of excess body weight, insulin resistance, and high triglyceride levels is called metabolic syndrome. All of these conditions cause fat to accumulate in liver cells by causing the body to synthesize more fat or by processing (metabolizing) and excreting fat more slowly. As a result, fat accumulates and is then stored inside liver cells. Just consuming a high-fat diet does not result in fatty liver.

Alcoholic fatty liver disease only happens in people who are heavy drinkers, especially those who have been drinking for a long period of time. The risk is higher for heavy drinkers who are women, have obesity, or have certain genetic mutations.

Rarely, fat accumulates in the liver during late pregnancy. This disorder, called fatty liver of pregnancy or microvesicular steatosis, is usually considered a different disorder from fatty liver.

Fatty liver prevention

The way to prevent non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is to follow the same lifestyle advice given to people who already have the condition, including:

- Eat a healthy diet. Eat a healthy diet that’s rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains and healthy fats.

- Limit alcohol, simple sugars and portion sizes. Avoid sugary drinks like soda, sports drinks, juices and sweet tea. Drinking alcohol can damage your liver and should be avoided or minimized.

- Keep a healthy weight. If you are overweight or obese, work with your health care team to gradually lose weight. If you are a healthy weight, work to keep it by eating a healthy diet and exercising.

- Exercise. Be active most days of the week. Get an OK from your health care team first if you haven’t been exercising regularly.

Fatty liver symptoms

Fatty liver usually causes no symptoms. Some people may feel tired or generally unwell or have vague abdominal discomfort in the upper right part of their abdomen. The liver tends to enlarge and can be detected by doctors during a physical examination.

More commonly, people notice symptoms once fatty liver has progressed to cirrhosis of the liver. When cirrhosis develops, you may experience:

- Nausea.

- Loss of appetite.

- Unexplained weight loss.

- Yellowish skin and whites of the eyes (jaundice).

- Swelling in your abdomen (ascites)

- Swelling in your legs, feet or hands (edema).

- Bleeding (that your doctor finds in your esophagus, stomach or rectum).

Fatty liver disease complications

In many people, fatty liver by itself doesn’t cause too many problems. But in some people the fatty liver gets inflamed, causing a more serious condition called non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH. Ongoing inflammation may scar the liver, which can lead to cirrhosis. This is a serious illness. A few people who get cirrhosis of the liver develop liver cancer. Some people who develop severe cirrhosis of the liver need to have a liver transplant.

People with fatty liver have an increased risk of heart attack and stroke.

Fatty liver diagnosis

If your doctor suspects fatty liver, he may ask about your alcohol use. This information is crucial. Continued and excessive alcohol use can cause severe liver damage.

Your doctor will also ask about your diet and lifestyle factors that may make you more likely to develop non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), such as a lack of physical activity, eating a diet high in sugar, or drinking sugary beverages.

However, because fatty liver causes no symptoms in most cases, it frequently comes to medical attention when tests done for other reasons point to a liver problem. This can happen if your liver looks unusual on ultrasound or if you have an abnormal liver enzyme test.

Tests done to pinpoint the diagnosis and determine disease severity include:

Blood tests

- Complete blood count

- Liver enzyme and liver function tests. Your doctor may suspect you have NAFLD if your blood test shows increased levels of the liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST).

- Tests for chronic viral hepatitis (hepatitis A, hepatitis C and others)

- Celiac disease screening test

- Fasting blood sugar

- Hemoglobin A1C (HbA1c), which shows how stable your blood sugar is

- Lipid profile, which measures blood fats, such as cholesterol and triglycerides

Your doctor may use the results of routine blood tests to calculate special scores, such as the FIB-4 or APRI. These scores can help doctors identify or rule out advanced liver fibrosis, or scarring.

Imaging procedures

Imaging procedures used to diagnose fatty liver include:

- Abdominal ultrasound, which is often the initial test when liver disease is suspected.

- Computerized tomography (CT) scanning or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen. These techniques lack the ability to distinguish NASH from NAFLD, but still may be used.

- Transient elastography, an enhanced form of ultrasound that measures the stiffness of your liver. Liver stiffness indicates fibrosis or scarring.

- Magnetic resonance elastography, works by combining MRI imaging with sound waves to create a visual map (elastogram) showing the stiffness of body tissues.

Liver biopsy

If other tests are inconclusive, your doctor may recommend a procedure to remove a sample of tissue from your liver (liver biopsy). Liver biopsy is the only test that can prove a diagnosis of NASH and show clearly how severe the disease is. For liver biopsy, a doctor gives a local anesthetic to lessen any pain, then inserts a long hollow needle through the skin and into the liver to obtain a small piece of liver tissue for examination under a microscope. The tissue sample is examined in a laboratory to look for signs of inflammation and scarring.

A liver biopsy can be uncomfortable, and it does have small risks that your doctor will review with you in detail.

A liver biopsy can help determine whether fatty liver is present, whether it resulted from alcohol or certain other specific causes, and how severe the liver damage is.

Fatty liver treatment

There are no medicines to treat fatty liver disease. Treatment of fatty liver focuses on controlling or eliminating the cause of fatty liver. Lifestyle modifications and weight loss are the mainstays of the treatment 15. Treatment also involves glycemic (blood sugar) and lipid control. For patients with significant obesity, gastric bypass or other weight loss surgical modalities should be considered. Weight loss is proven to reduce fatty liver. Evidence available suggests that weight loss of 3% to 5% of body weight is necessary to notice an improvement in fatty liver, but a greater loss (up to 10%) is necessary to improve liver inflammation 16, 17.

Patients should also abstain from alcohol or liver toxic drugs.

If your fatty liver is caused by alcohol, then the most important thing to do is give up alcohol. This will prevent you from developing a more serious condition.

If you have non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), you will probably be advised to:

- Drink no or very little alcohol

- Follow a healthy diet and avoid sugar. Eat a healthy diet that’s rich in fruits, vegetables and whole grains, and keep track of all calories you take in.

- Lose weight. If you’re overweight or obese, reduce the number of calories you eat each day and increase your physical activity in order to lose weight. Calorie reduction is the key to losing weight and managing this disease. If you have tried to lose weight in the past and have been unsuccessful, ask your doctor for help.

- Exercise regularly. Aim for at least 30 minutes of exercise most days of the week. If you’re trying to lose weight, you might find that more exercise is helpful. But if you don’t already exercise regularly, get your doctor’s OK first and start slowly.

- Control your blood sugar. Follow your doctor’s instructions to stay in control of your diabetes. Take your medications as directed and closely monitor your blood sugar.

- Treat high cholesterol if you have it. A healthy plant-based diet, exercise and medications can help keep your cholesterol and your triglycerides at healthy levels.

- Avoid medicines that can affect your liver

- Quit smoking

Your doctor can help you. They may refer you to a dietitian, drug and alcohol counselor or specialist.

Avoiding all fat in your diet is not necessary. However, your doctor may recommend that you avoid certain foods, such as those that contain fructose (the sugar in fruit) and trans fats (a type of fat).

There is no specific medicine for fatty liver disease. However, depending on your situation, your doctor may advise that you take medicine to lower your lipid levels, or improve the way your body manages glucose.

No medicines have been approved to treat nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by the US Food and Drug Administration or by the European Medicines Agency. However, researchers are studying medicines that may improve these conditions. Medicine options include Metformin, Vitamin E, fish oil, Orlistat (an inhibitor of gastric and pancreatic lipase), and Sibutramine. It is important to notice that the evidence behind these pharmacological modalities is weak 13.

According to the European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines 18, drug therapy should be reserved for: Progressive NASH (bridging fibrosis and cirrhosis); early-stage NASH at high risk for disease progression (age > 50 years, metabolic syndrome, diabetes mellitus or increased ALT) 19; active NASH with high necroinflammatory activities 20. Similarly, in the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines, a pharmacological approach is recommended only for patients with NASH and fibrosis 8. In the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance, just people with an advanced liver fibrosis (enhanced liver fibrosis [ELF] test > 10.51) are proposed for drug treatment 21. In the Italian Association for the Study of the Liver position paper, drug therapy is suggested for patients who are at high risk for disease progression22.

All guidelines acknowledge that any medicines prescribed explicitly for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease should be considered as an off-label treatment and that the decision should be discussed with the patient, carefully balancing the benefits and the safety. However, there are wide disagreement among the guidelines with regard to possibly helpful drugs.

- Metformin: Due to the evidence of its limited efficacy in improving the histological features of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease 23, metformin is not recommended by any guidelines to specifically treat NAFLD 15.

- Pioglitazone: Pioglitazone, a thiazolidinedione, is a peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor (PPAR) gamma agonist with insulin-sensitising effects. Treatment with pioglitazone improves insulin sensitivity, aminotransferases, steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning in patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) and prediabetes or type 2 diabetes 24. The PIVENS trial (a large multicenter randomized control trial) compared low dose pioglitazone (30 mg/d) vs vitamin E (800 UI/d) vs placebo for two years in patients without overt diabetes 25. Pioglitazone improved all histological features (except for fibrosis) and achieved resolution of NASH more often than placebo 25. The histological benefit occurred together with ALT improvement and partial correction of insulin resistance. The main side effects of glitazones are weight gain 26 and bone fractures in women 27. The use of pioglitazone for the treatment of NAFLD is endorsed both by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines, with significant limitations. According to the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, pioglitazone should be prescribed only in second and third level centers, after a careful evaluation 21. Whereas the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases, pioglitazone is reserved for patients with biopsy-proven NASH 8. The European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines are more cautious, generically suggesting to consider pioglitazone for the treatment of diabetes in patients with a concurrent NAFLD 18. Even the Asia-Pacific and the Italian guidelines acknowledge the potential benefits of pioglitazone, however, suggest that more evidence should be available before a firm recommendation can be made 28, 22.

- Vitamin E: Vitamin E is an anti-oxidant and has been investigated to treat nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). In the PIVENS trial, vitamin E at a dose of 800 IU/d of α-tocopherol for 96 wk was associated with a decrease in serum aminotransferases and histological improvement in steatosis, inflammation, and ballooning and resolution of steatohepatitis in adults with NASH 25. Long-term safety of vitamin E is under dispute, with two different meta-analyses leading to conflicting results when analysing the all-cause mortality in patients treated with t doses of > 800 IU/d 29, 27. Similarly to pioglitazone, vitamin E is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence and American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases guidelines (limited to biopsy-proven NASH in the latter case) 21, 8. Italian Association for the Study of the Liver and European Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines call for more evidence before any recommendation, while Asia-Pacific guidelines advice against the use of vitamin E which is described as not beneficial by the current evidence 28.

- Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) analogues: Liraglutide is a glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonist. Glucagon is an important hormone in the regulation of energy handling in your body. Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists are a class of drugs that improve control of your blood sugar, cause weight loss and improve blood lipids. They also improve cardiovascular outcomes 30. Therefore, they are approved for the treatment of diabetes and obesity. Liraglutide is one of these GLP-1 receptor agonists and has been tested in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial consisting of 52 patients with biopsy-proven NASH at a daily dose of 1.8 mg in 1-year study 31. NASH resolved significantly more frequently in liraglutide-treated patients than placebo-treated patients. Treatment with liraglutide also led to a trend in improvement of fibrosis stage. The same holds true for semaglutide, which was already shown to improve liver blood tests in patients with type 2 diabetes and obesity 32. Semaglutide was tested at several dose regimens for a treatment period of 1.5 years. NASH resolved significantly more frequently in patients treated with the higher doses of semaglutide than in patients that received placebo 33. Fibrosis also tended to improve, but this result was not strong enough to be considered as a positive endpoint of the study. However, both the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommendations state that there is still too few evidence to support the use of GLP-1 analogues to specifically treat liver disease in patients with NAFLD 21, 8. The remaining guidelines also agree on this point, however also state that further evidence are needed to prove the efficacy of these drugs. In particular, the Asian Pacific Association for the Study of the Liver guidelines consider some more elements in their recommendations. On the one hand, glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) agonists appeared to reduce glycated hemoglobin more efficiently in Asian patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus 34. On the other hand, there has been no study on Asian NASH patients, even if the pharmacokinetics of GLP-1 agonists do not appear to differ between Asian and non-Asian patients according to preliminary evidence 35. You can consider using these drugs if you meet the diagnosis for which these drugs are approved by the regulatory authorities. For example, if you are living with type 2 diabetes, it could be worthwhile to consider including pioglitazone or glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) receptor agonists in the treatment of your type 2 diabetes, as they are also beneficial for your liver. This needs to be discussed with the doctors that treat your diabetes.

- Statins: Historically, the use of statins in patients with chronic liver diseases has been considered as potentially troublesome due to the risk of hepatotoxicity. At the same time, a considerable portion of NAFLD patients usually receives statins because of their multiple cardiovascular risk factors. Consequently, the primary concern of the guidelines is the safety of statins. In this regard, a recent review underlined the safety of statin and their efficacy in reducing the associated cardiovascular morbidity in patients with NAFLD, including those with slightly elevated alanine transaminases (up to 3 × reference upper limit) 36. All of the guidelines agree about the safety of prescribing statins (or continuing an ongoing statin therapy) in patients with NAFLD, even with compensated cirrhosis. However, routine prescription of a statin is not recommended in patients with decompensated cirrhosis and acute liver failure 37.

- Silymarin: Silymarinis a complex mixture of six major flavonolignans (silybins A and B, isosilybins A and B, silychristin, and silydianin), as well as other minor polyphenolic compounds 38. In a randomized, double-blinded, placebo-controlled study on patients with biopsy-proven NASH, silymarin dosage of 700 mg three times daily for 48 wk resulted in a significantly higher percentage of fibrosis reduction compared with placebo (22.4% vs 6.0%) 39. The dosage was safe and well tolerated 39. Silymarin is mentioned as a potentially useful treatment for NASH in Asia-Pacific guidelines only. However, optimal dose and duration still require further studies before a full recommendation 28.

For patients with advanced disease and cirrhosis, liver transplantation might have to be considered.

What food should I eat for healthy liver function?

Eating a healthy diet and being a healthy weight can often help avoid damage to your liver.

Eating the right types of food helps you and your liver stay healthy. So, try to eat a mix of:

- Milk, yogurt and cheese

- Meat and fish (fresh or tinned low salt) and/or eggs, tofu, nuts and seeds

- Fruits (fresh or tinned low sugar)

- Vegetables, beans and legumes (fresh or tinned low salt)

- Grains (like breads, cereals, rice and pasta)

- And drinking lots of water.

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) now called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) is a liver disease in which too much fat builds up in your liver and this buildup of fat is not caused by heavy alcohol use 40, 41. It is normal for your liver to contain some fat. However, if more than 5% to 10% percent of your liver’s weight is fat, then it is called a fatty liver (steatosis). Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is the most common form of liver disease in the world, with the highest rates being reported in South America and the Middle East, followed by Asia, the USA, and Europe; NAFLD is less common in Africa 42, 43, 44, 45. This study found that approximately 900 million people suffered from NAFLD in 2017 43. When heavy alcohol use causes fat to build up in your liver, this condition is called alcoholic fatty liver disease (AFLD). NAFLD is a growing cause of end-stage liver disease and has been recognized as a cause of liver cancer (hepatocellular cancer [HCC]), even in the absence of underlying cirrhosis 46.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is seen most often in people who are overweight or obese. NAFLD is becoming more common, especially in North African and Middle Eastern countries (including Qatar, Libya and Kuwait) and Western nations as the number of people with obesity and type 2 diabetes rises 47, 48. Global reports relating to the epidemiology of NAFLD have estimated a global prevalence of NAFLD between 25% and 35%, with Europe as high as 30%, 35% in South American countries and 35% in North America 49, 50, 51, 52, 49, 53.

Well-established risk factors for NAFLD include obesity, type 2 diabetes, an unhealthy diet (eg, high intake of red meat and processed meat) and physical inactivity 54, 55, 56, 57, 58. Of these, an unhealthy lifestyle is deemed to be the most important contributor to NAFLD 59. Key lifestyle factors include an increased intake of glucose, fructose, and saturated fat, induced hepatic de novo lipogenesis, subclinical inflammation in the adipose tissue and liver, and insulin resistance in adipose tissue, the liver, and skeletal muscle 60. These lifestyle factors are also accompanied by an increased risk of type 2 diabetes 60.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) ranges in severity from nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) to a more severe form of the disease called nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) 41.

- Nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL). Nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) is a form of NAFLD in which you have fat in your liver but little or no inflammation or liver damage. Nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) typically does not progress to cause liver damage or complications. However, nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) can cause pain from enlargement of the liver and have a higher risk for other health problems 61.

- Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is the form of NAFLD in which you have inflammation of the liver and liver damage, in addition to fat in your liver. The inflammation and liver damage of NASH can cause fibrosis, or scarring, of the liver. NASH may lead to cirrhosis, in which the liver is scarred and permanently damaged. Cirrhosis can lead to liver cancer. Furthermore, people with NASH have an increased chance of dying from liver-related causes 62. It is hard to tell apart NAFLD from NASH without a clinical evaluation and testing.

Scientists are not sure why some people with NAFLD have NASH while others have nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) 63. People typically develop one type of NAFLD or the other, although sometimes people with one form are later diagnosed with the other form of NAFLD. The majority of people with NAFLD have nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL). Only a small number of people with NAFLD have NASH. Experts guess that about 10% to 24% of Americans have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and about 1.5% to 6.5% have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) 61, 64.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is more common in people who have certain diseases and conditions, including obesity, and conditions that may be related to obesity, such as type 2 diabetes 63. Studies suggest that one-third to two-thirds of people with type 2 diabetes have NAFLD 61. Research also suggests that NAFLD is present in up to 75% of people who are overweight and in more than 90% of people who have severe obesity 65, 66.

NAFLD can affect people of any age, including children. Research suggests that close to 10% of U.S. children ages 2 to 19 have NAFLD 67. However, people are more likely to develop NAFLD as they age.

While NAFLD occurs in people of all races and ethnicities, it is most common among Hispanic individuals, followed by non-Hispanic whites and Asian Americans, including those of East Asian and South Asian descent 62, 68. NAFLD is less common among non-Hispanic Blacks 62. On average, Asian Americans with NAFLD have a lower body mass index (BMI) than non-Hispanic whites with NAFLD 68. Experts think that genes may help explain some of the racial and ethnic differences in NAFLD 63.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) usually is a silent disease with few or no symptoms 69. When it does, they may include:

- Fatigue.

- Not feeling well, or malaise.

- Pain or discomfort in the upper right belly area.

People with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) have a higher risk for certain health problems, including:

- Cardiovascular disease, which is the most common cause of death in people who have NAFLD 62

- Type 2 diabetes

- Metabolic syndrome

- Conditions that may be part of metabolic syndrome, such as high blood pressure and abnormal levels of fats—cholesterol and triglycerides—in the blood.

Early-stage NAFLD does not usually cause any harm, but it can lead to serious liver damage, including cirrhosis, if it gets worse.

Having high levels of fat in your liver is also associated with an increased risk of serious health problems, such as type 2 diabetes, high blood pressure and kidney disease.

If you already have diabetes, NAFLD increases your chance of developing heart problems.

If detected and managed at an early stage, it’s possible to stop NAFLD getting worse and reduce the amount of fat in your liver.

Doctors recommend weight loss, done through a combination of calorie reduction, exercise, and healthy eating, to treat nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) 70, 71, 72. Weight loss can reduce fat, inflammation, and fibrosis or scarring in your liver 73.

If you are overweight or have obesity, losing weight by making healthy food choices, limiting portion sizes, and being physically active can improve nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Losing at least 3% to 5% of your body weight can reduce fat in the liver 74, 62. You may need to lose up to 7% to 10% of your body weight to reduce liver inflammation and fibrosis 75, 72, 76, 62. Physical activity alone, even without weight loss, is also beneficial.

The best way to lose weight is done by:

- Reducing the number of calories you eat. Keeping track of the calories you consume every day and employing portion control can help.

- Eating a healthy diet that’s rich in fruits and vegetables, whole grains and low in saturated fats. Limit animal-based foods, like red meat which is high in saturated fats, and eat more plant-based foods like beans, legumes, and nuts. Use good fats like olive oil. This is the basis for the Mediterranean diet – which isn’t a diet in the traditional sense, but a healthy way of eating inspired by the eating habits of people living in the Mediterranean area and is often recommended by doctors as a way to reduce some of the risk factors associated with fatty liver disease.

- Limiting the amount of salt and sugar in your diet, particularly sugar-sweetened beverages, like soda, juices, sports drinks, and sweetened tea. High consumption of fructose, one of the main sweeteners in these beverages, increases your odds of developing obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and NAFLD.

- Limit your intake of saturated fats, which are found in meat, poultry skin, butter, shortening, milk and dairy products (except fat-free versions). Replace them with monounsaturated fats (olive, canola, and peanut oils) and polyunsaturated fats (corn, safflower, soybean oils, and many types of nuts). Particularly helpful in reducing heart disease are omega-3 fatty acids, a type of polyunsaturated fat found in oily fish such as salmon, flaxseed oil, and walnuts. Healthy eating combined with exercise – and taking cholesterol-lowering medications if prescribed by your doctor – will help keep your cholesterol and triglyceride levels where they need to be.

- Exercise and be more active – exercise is important for many reasons; it can help with weight control, boost your immune system, and alleviate stress and depression. Aim for at least 150 minutes of exercise a week. Depending on how much weight you’re trying to lose, you may need to up that amount. Getting exercise doesn’t mean you have to go to a gym – walking, gardening, and even housework counts. However, if you don’t already exercise, get your doctor’s okay first and build slowly. The goal is to participate in exercise of a moderate intensity (examples include light jogging, biking, swimming or playing a sport that boosts your heart rate and results in sweating).

Doctors recommend gradually losing weight to improve NAFLD. Rapid weight loss and malnutrition can make liver disease worse.

If you’ve tried to lose weight in the past without success, talk to your dietitian about getting help. You may also be a candidate for a medically-supervised weight loss program that employs medication along with diet and exercise. Alternatively, there are weight-loss (bariatric) surgical procedures and endoscopic therapies that work by either physically limiting the amount of food your stomach can hold, or reducing the amount of nutrients and calories your body absorbs. Talk to your doctor about which option may be best for you.

Figure 2. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD)

Figure 3. Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progression

Footnotes: Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) encompasses a range of liver damage, from simple accumulation of fat in liver cells, named steatosis, to more severe forms of the diseases such as nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), involving inflammation which can lead to fibrosis and cirrhosis. In the “multiple-hit” theory of progression, the first cause or “first-hit” in NAFLD is insulin resistance, obesity, type 2 diabetes, and metabolic syndrome. As the first hit occurs, free fatty acids are stored in the liver as triglycerides, resulting in simple steatosis. Disease progresses when multiple factors, or “multi-hits”, such as oxidative stress, inflammatory mediators, apoptosis, and mitochondrial dysfunction cause liver damage.

[Source 70 ]Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease causes

Scientists don’t know exactly why fat builds up in some livers and not others. They also don’t fully understand why some fatty livers turn into non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD).

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are both linked to the following 77, 78, 79, 80, 81:

- Genetics. Researchers have found that certain genes may make you more likely to develop NAFLD. These genes may help explain why NAFLD is more common in certain racial and ethnic groups. Studies have identified many genetic changes that may be associated with the development of NAFLD and NASH. Among these is a particular variation in the PNPLA3 gene 82. The PNPLA3 gene provides instructions for making a protein called adiponutrin, which is found in fat cells (adipocytes) and liver cells (hepatocytes). The function of this protein is not well understood, but it is thought to help regulate the production and breakdown of fats (lipogenesis and lipolysis) and the development of adipocytes. Studies indicate that the activity (expression) of the PNPLA3 gene decreases during periods without food (fasting) and increases after eating, suggesting that the amount of adiponutrin protein produced is regulated as needed to help process and store fats in the diet. The PNPLA3 gene variation associated with NAFLD is thought to lead to increased production and decreased breakdown of fats in the liver. Research is ongoing to determine how this and other genetic changes contribute to the development of NAFLD and its complications.

- Overweight or obesity.

- Insulin resistance, which happens when your cells don’t take up sugar in response to the hormone insulin.

- Type 2 diabetes, sometimes called high blood sugar or hyperglycemia.

- High levels of fats (abnormal levels of cholesterol—high total cholesterol, high LDL cholesterol, or low HDL cholesterol), especially triglycerides, in the blood.

These combined health problems may contribute to a fatty liver. However, some people get NAFLD even if they do not have any risk factors.

Risk factors for developing non-alcoholic fatty liver disease

Many diseases and health problems can increase your risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), including:

- Family history of fatty liver disease or obesity.

- Growth hormone deficiency, which means the body doesn’t make enough hormones to grow.

- High cholesterol.

- High levels of triglycerides in the blood.

- Insulin resistance.

- Metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is a group of traits and medical conditions linked to overweight and obesity. Doctors define metabolic syndrome as the presence of any three of the following:

- large waist size

- high levels of triglycerides in your blood

- low levels of HDL cholesterol in your blood

- high blood pressure

- higher than normal blood glucose levels or a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- Obesity, especially when fat is centered in the waist.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

- Obstructive sleep apnea.

- Type 2 diabetes.

- Underactive thyroid, also called hypothyroidism.

- Underactive pituitary gland, or hypopituitarism.

If you have risks for NAFLD and also drink alcohol excessively, you could have both NAFLD and alcohol-associated liver disease at the same time. No tests can easily tell how much each plays a role.

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is more likely in these groups:

- People older than 50.

- People with certain genetic risk factors.

- People with obesity.

- People with diabetes or high blood sugar.

- People with symptoms of metabolic syndrome, such as high blood pressure, high triglycerides and a large waist size.

Having more of these health conditions increases your chances of developing NASH. Losing weight may cause nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) to switch to nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and regaining weight may cause nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) to switch to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease prevention

You may be able to prevent non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) by being physically active regularly, eating a healthy diet, limiting your portion sizes, and maintaining a healthy weight.

To reduce your risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH):

- Eat a healthy diet. Eat a healthy diet that’s rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains and healthy fats.

- Limit alcohol, simple sugars and portion sizes. Avoid sugary drinks like soda, sports drinks, juices and sweet tea. Drinking alcohol can damage your liver and should be avoided or minimized.

- Keep a healthy weight. If you are overweight or obese, work with your health care team to gradually lose weight. If you are a healthy weight, work to keep it by eating a healthy diet and exercising.

- Exercise. Be active most days of the week. Get an OK from your health care team first if you haven’t been exercising regularly.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease stages

Staging and grading systems have been developed to characterize the histological changes in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), mainly as a tool for clinical research.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Grades 83, 84, 85, 86, 87:

- Grade 0 (Normal) is defined as a normal liver containing fat in less than 5% of liver cells (hepatocytes)

- Grade 1 (Mild): Fatty liver (steatosis) up to 66%, occasional ballooning in zone 3, scattered polymorphs with or without lymphocytes, mild or no portal inflammation

- Grade 2 (Moderate): Any degree of steatosis, obvious ballooning predominantly in zone 3, intralobular inflammation with polymorphs and chronic inflammation, and mild to moderate portal inflammation

- Grade 3 (Severe): Panacinar steatosis, ballooning, and obvious disarray predominantly in zone 3, intralobular inflammation with scattered polymorphs with or without mild chronic and mild to moderate portal inflammation

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) Stages 83, 84, 85, 86, 87, 88, 89, 90:

- Stage 0: No fibrosis

- Stage 1: Zone 3 perisinusoidal fibrosis only

- Stage 2: Zone 3 perisinusoidal and periportal fibrosis

- Stage 3: Bridging fibrosis

- Stage 4: Cirrhosis

Progression of the fibrosis stage to a cirrhotic scarred liver can vary between individuals, with cirrhosis occurring up to 15 to 20 years after initial diagnosis 89, 91. The median survival rate for patients with compensated cirrhosis is approximately 9 to 12 years, however, patients with decompensated cirrhosis have a significantly lower median survival rate of approximately 2 years 92. Patients in the compensated stage are frequently asymptomatic, and often remain undiagnosed 92. Therefore, early detection of cirrhotic patients who are still in the compensated stage is crucial, as early diagnosis could prevent or slow down disease progression 70.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease symptoms

Often, there are no symptoms of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) in its early stages. It is more common for symptoms to develop once significant damage to the liver has occurred. Some symptoms of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) may include:

- Discomfort or pain in the abdomen (belly area)

- Fatigue (feeling very tired)

- Irritability

- Headaches

- Difficulty concentrating

- Depression and anxiety

- Changes in skin color near joints and the back of the neck/upper back

If cirrhosis develops, the following symptoms may be present:

- Jaundice (yellowing of the skin and whites of the eyes)

- Itchy skin

- Swelling of the lower stomach

- Bruising easily

- Dark urine

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease complications

Severe liver scarring, or cirrhosis, is the main complication of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Cirrhosis happens because of liver injury, such as the damage caused by inflammation in NASH. As the liver tries to stop inflammation, it creates areas of scarring, also called fibrosis. With ongoing inflammation, fibrosis spreads and takes up more liver tissue.

If nothing is done to stop the scarring, cirrhosis can lead to:

- Fluid buildup in the stomach area, called ascites.

- Swollen veins in your esophagus, or esophageal varices, which can rupture and bleed.

- Confusion, sleepiness and slurred speech, also called hepatic encephalopathy.

- Overactive spleen, or hypersplenism, which can cause too few blood platelets.

- Liver cancer.

- End-stage liver failure, which means the liver has stopped working.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease diagnosis

Doctors use your medical history, a physical exam, and tests to diagnose nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) including nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). Because nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) typically causes no symptoms, it is often found when tests done for other reasons point to a liver problem. For example, your blood work may show high levels of liver enzymes, or an ultrasound of your abdomen might reveal that your liver looks enlarged, which can lead to more testing. Doctors use blood tests, imaging tests, and sometimes liver biopsy to diagnose NAFLD and to tell the difference between nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Medical history

Your doctor will ask if you have a history of health conditions or diseases that make you more likely to develop NAFLD, such as:

- overweight or obesity

- insulin resistance or type 2 diabetes

- high levels of triglycerides or abnormal levels of cholesterol in your blood

- metabolic syndrome

Your doctor will ask about your diet and lifestyle factors that may make you more likely to develop liver disease or fat in your liver.

- What medicines you take to determine whether a medicine might be causing your fatty liver.

- Your doctor will ask about your alcohol intake to find out whether fat in your liver is a sign of alcohol-associated liver disease or NAFLD. Medical tests cannot show whether alcohol is the cause of fat in the liver, so it’s important to be honest with your doctor.

- What your diet is like (eating a diet high in sugar, or drinking sugary beverages), your level of physical activity, and other lifestyle factors that can contribute to the likelihood of developing NAFLD.

Physical exam

During a physical exam, a doctor usually examines your body and checks your weight and height to calculate your body mass index (BMI). Your BMI estimates how much you should weigh based on your height. Most experts say that a BMI greater than 30 (obesity) is unhealthy. If you want to figure out your BMI on your own, there are many websites that calculate it for you when you enter your height and weight. If you have more or less muscle than is normal, your BMI may not be a perfect measure of how much body fat you have. Your doctor may also take your waist circumference and waist-to-hip ratio into consideration.

Your doctor will look for signs of nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), such as:

- an enlarged liver

- signs of insulin resistance, such as darkened skin patches over your knuckles, elbows, and knees

- signs of cirrhosis, such as an enlarged spleen, ascites, spiderlike blood vessels on your skin, yellowing of your skin and whites of your eyes (jaundice) and muscle loss

Blood tests

Your doctor may take a blood sample from you and send the sample to a lab.

Your blood tests may include:

- Complete blood count.

- Iron studies, which show how much iron is in your blood and other cells.

- Liver enzyme and liver function tests.

- Tests for chronic viral hepatitis (hepatitis A, hepatitis C and others).

- Celiac disease screening test.

- Fasting blood sugar.

- Hemoglobin A1C, which shows how stable your blood sugar is.

- Lipid profile, which measures blood fats, such as cholesterol and triglycerides.

Your doctor may suspect you have NAFLD if your blood test shows increased levels of the liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). The cells in your liver contain proteins called enzymes, which are chemicals that help the liver do its work. When liver cells are damaged or destroyed, the enzymes in the cells leak out into the blood where they can be measured by blood tests. Liver enzyme testing usually checks the blood for two main enzymes 75, 93:

- ALT (alanine aminotransferase)

- AST (aspartate aminotransferase)

If your liver is damaged due to inflammation, the level of these enzymes may be higher than normal. However, ALT and AST levels do not tell you how much scarring (fibrosis) may be present in your liver or predict how much liver damage will develop. In some people with NAFLD these liver enzymes may be normal as well.

Fibrosis assessment tests

These blood tests result in a score that estimates your level of liver scarring or fibrosis. They include:

- AST-to-Platelet Ratio Index (APRI) score

- Fibrosis-4 (Fib-4) score. The fibrosis-4 scoring system uses a patients age, platelet count, AST (aspartate aminotransferase) and ALT (alanine aminotransferase) to determine a liver fibrosis score and can help to predict advanced fibrosis.

These scores can help doctors identify or rule out advanced liver fibrosis, or scarring.

Your doctor may perform additional blood tests to find out if you have other health conditions that may increase your liver enzyme levels.

Imaging tests

Your doctor may order tests that take images, or pictures, of your liver to help make the diagnosis of liver disease. Different types of images can be obtained by using various types of equipment. However, these tests can’t show inflammation or fibrosis, so your doctor can’t use these tests to find out whether you have nonalcoholic fatty liver (NAFL) or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). If you have cirrhosis, routine imaging tests may show nodules, or lumps, in your liver.

Your doctor may use the following imaging tests to help diagnose NAFLD:

- Abdominal ultrasound, which uses a device called a transducer that bounces safe, painless sound waves off your organs to create an image of their structure. Abdominal ultrasoundis often the first test used when liver disease is suspected.

- Computed tomography (CT) scan, which uses a combination of x-rays and computer technology to create images of your liver.

- Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which uses radio waves and magnets to produce detailed images of organs and soft tissues without using x-rays.

- Transient elastography, a newer type of ultrasound that measures the stiffness of your liver to determine if you have advanced liver fibrosis. Liver stiffness is a sign of fibrosis or scarring. Commonly used types of elastography are:

- Vibration-controlled transient elastography, a special type of ultrasound

- Sheer wave elastography, another type of ultrasound to detect increased liver stiffness

- Magnetic resonance elastography (MRE), is a newer, noninvasive test that combines features of ultrasound and MRI imaging to create a visual map showing gradients of stiffness throughout the liver. MRE has been shown to be a more reliable measure of liver stiffness in severely obese patients.

Liver biopsy

If other tests show signs of more-advanced liver disease or nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), or if your test results are unclear, your doctor may suggest a liver biopsy. Liver biopsy is a procedure to remove a small piece of tissue from your liver. It is usually done using a needle through the abdominal wall. The tissue sample is looked at in a lab for signs of inflammation and scarring. Liver biopsy is the only test that can prove a diagnosis of NASH and clearly shows the amount of liver damage.

Liver biopsy can show fibrosis at earlier stages than elastography can. However, doctors don’t recommend liver biopsy for everyone with suspected NAFLD. Your doctor may recommend a liver biopsy if you are more likely to have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) with advanced fibrosis or if your other tests show signs of advanced liver disease or cirrhosis. In some cases, doctors may recommend a liver biopsy to rule out other liver diseases.

During a liver biopsy, a doctor using a needle that is passed through the abdominal wall and into the liver will take small pieces of tissue from your liver. A pathologist will examine the tissue under a microscope to look for signs of damage or disease.

A liver biopsy can be uncomfortable, and it does have risks that your doctor will go over with you in detail.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease treatments

Doctors recommend weight loss, done through a combination of calorie reduction, exercise, and healthy eating, to treat nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) 70, 71, 72, 73. Weight loss can reduce fat, inflammation, and fibrosis or scarring in your liver 73.

If you are overweight or have obesity, losing weight by making healthy food choices, limiting portion sizes, and being physically active can improve nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD). Losing at least 3% to 5% of your body weight can reduce fat in the liver 74, 62. You may need to lose up to 7% to 10% of your body weight to reduce liver inflammation and fibrosis 75, 72, 76, 62. Physical activity alone, even without weight loss, is also beneficial.

The best way to lose weight is done by:

- Reducing the number of calories you eat. Keeping track of the calories you consume every day and employing portion control can help.

- Eating a healthy diet that’s rich in fruits and vegetables, whole grains and low in saturated fats. Limit animal-based foods, like red meat which is high in saturated fats, and eat more plant-based foods like beans, legumes, and nuts. Use good fats like olive oil. This is the basis for the Mediterranean diet – which isn’t a diet in the traditional sense, but a healthy way of eating inspired by the eating habits of people living in the Mediterranean area and is often recommended by doctors as a way to reduce some of the risk factors associated with fatty liver disease.

- Limiting the amount of salt and sugar in your diet, particularly sugar-sweetened beverages, like soda, juices, sports drinks, and sweetened tea. High consumption of fructose, one of the main sweeteners in these beverages, increases your odds of developing obesity, type 2 diabetes, metabolic syndrome, and NAFLD.

- Limit your intake of saturated fats, which are found in meat, poultry skin, butter, shortening, milk and dairy products (except fat-free versions). Replace them with monounsaturated fats (olive, canola, and peanut oils) and polyunsaturated fats (corn, safflower, soybean oils, and many types of nuts). Particularly helpful in reducing heart disease are omega-3 fatty acids, a type of polyunsaturated fat found in oily fish such as salmon, flaxseed oil, and walnuts. Healthy eating combined with exercise – and taking cholesterol-lowering medications if prescribed by your doctor – will help keep your cholesterol and triglyceride levels where they need to be.

- Exercise and be more active – exercise is important for many reasons; it can help with weight control, boost your immune system, and alleviate stress and depression. Aim for at least 150 minutes of exercise a week. Depending on how much weight you’re trying to lose, you may need to up that amount. Getting exercise doesn’t mean you have to go to a gym – walking, gardening, and even housework counts. However, if you don’t already exercise, get your doctor’s okay first and build slowly. The goal is to participate in exercise of a moderate intensity (examples include light jogging, biking, swimming or playing a sport that boosts your heart rate and results in sweating).

Doctors recommend gradually losing weight to improve NAFLD. Rapid weight loss and malnutrition can make liver disease worse.

If you’ve tried to lose weight in the past without success, talk to your dietitian about getting help. You may also be a candidate for a medically-supervised weight loss program that employs medication along with diet and exercise. Alternatively, there are weight-loss (bariatric) surgical procedures and endoscopic therapies that work by either physically limiting the amount of food your stomach can hold, or reducing the amount of nutrients and calories your body absorbs. Talk to your doctor about which option may be best for you.

Patients with NASH are to be followed by liver specialists or gastroenterologists. NASH with cirrhosis requires hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) surveillance with an ultrasound every six months 77.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease diet

If you have NAFLD, your doctor may suggest changes to your diet such as:

- Limiting your intake of fats, which are high in calories and increase your chance of developing obesity.

- Replacing saturated fats and trans fats in your diet with unsaturated fats, especially omega-3 fatty acids, which may reduce your chance of heart disease if you have NAFLD.

- Eating more low-glycemic (low GI) index foods such as most fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. These foods affect your blood glucose less than high-glycemic index foods, such as white bread, white rice, and potatoes.

- Avoiding foods and drinks that contain large amounts of simple sugars, especially fructose. Fructose is found in sweetened soft drinks, sports drinks, sweetened tea, and juices. Table sugar, called sucrose, is rapidly changed to glucose and fructose during digestion and is therefore a major source of fructose.

If you have NAFLD, you should minimize alcohol use, which can further damage your liver.

Evidence has suggested that the ketogenic diet (diet with very low in carbohydrate and very high in fat = 75-80% fat, 10-15% protein and ≤ 5% carbohydrate) is an effective treatment for NAFLD 95, 73, 96, 70. Ketogenesis is a metabolic process resulting in the production of ketone bodies, namely acetoacetate, beta-hydroxybutyrate and acetone, which act as alternative energy sources 97, 95. The ketogenic diet has been shown to change hepatic mitochondrial fluxes and redox state as well as significantly reducing liver fat content and liver insulin resistance 98. These changes were found to be accompanied by an increase in the net hydrolysis of liver triglycerides, a decrease in endogenous glucose production, and lower serum insulin levels 98. Beta-hydroxybutyrate has also been shown to interact with inflammasomes 99, 100 and neutralize reactive oxygen species (ROS) 101, leading to a reduction in inflammatory cytokines and oxidative damage via its antioxidant capacity. These findings suggest a ketogenic diet can contribute to the reversal of NAFLD through improvement of insulin resistance and cellular redox function 70.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease medication

No medicines have been approved to treat nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) 102, 77, 70.

Weight loss surgery

Weight loss surgery also called bariatric surgery been shown to be an effective treatment for nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) by improving overall liver health via facilitating weight loss, improving insulin sensitivity, and subsiding inflammation 103, 104. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy are the most prevalent weight loss surgical procedures, which lead to significant weight loss and metabolic health improvements 105.

Several research studies have investigated the impact of weight loss surgery in NAFLD and have shown positive results. Studies have indicated that weight loss surgery resulted in significant improvements in liver enzymes and histology, with a decrease in liver fat and fibrosis. Results from two meta-analyses have shown that treatment of NAFLD using weight loss surgery resulted in a biopsy-confirmed resolution of steatosis (56%-66%), inflammation (45%-50%), ballooning degeneration (49%-76%), and fibrosis (25%-40%), as well as showing a decrease in NAS scoring 105, 106, 107. Weight loss surgery has therefore proven to be effective in ameliorating NAFLD, however, it is important to clarify which type of weight loss surgery is most effective. A study by Baldwin et al 108 compared Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB) and laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy against its effectiveness at improving AST and ALT concentration, NAS and NAFLD fibrosis score. Overall, both procedures reduce AST and ALT levels, however, laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy showed slightly more favourable results 104. Another study has shown NAS scoring reduced significantly in patients who underwent both surgery types 12-mo after the surgery 104. Roux-en-Y gastric bypass patients had a more significantly decreased steatosis and superior improvement in plasma lipid profile 109. Furthermore, weight loss surgery has been demonstrated to lower the risk of liver-related complications and death in individuals with NAFLD. Weight loss surgery can therefore be considered as a promising treatment option for those with NAFLD who are overweight or obese.

Protect your liver

Don’t do things that put extra stress on your liver:

- Avoid drinking alcohol.

- Take medications and over-the-counter drugs only as instructed by your doctor.

- Be cautious about taking dietary supplements. Certain vitamins and minerals – like vitamins A, iron, and niacin – can be harmful to your liver in higher doses than necessary or prescribed.

Check with your doctor before trying any herbal remedies. Just because a product is called “natural,” does not mean it’s safe. - Get vaccinated for hepatitis A and hepatitis B. If you get hepatitis A or B, along with fatty liver, it’s more likely to lead to liver failure.

- Manage your diabetes. Follow your doctor’s advice to manage your diabetes. Take your medicines as told by your care team and watch your blood sugar closely.

- Lower your cholesterol and blood pressure. Improve your cholesterol levels and blood pressure if they are high. A healthy diet, exercise and medicines can help keep your cholesterol, triglycerides and blood pressure at healthy levels.

Vitamin E, which is an antioxidant, in theory could help protect the liver by reducing or canceling out the damage caused by inflammation. But more research is needed. Some evidence suggests vitamin E supplements may be helpful for people with liver damage due to NAFLD and NASH who don’t have type 2 diabetes. Researchers in one study found that a daily dose of the natural form of vitamin E – the kind that comes from food sources and isn’t made in a laboratory – improved NASH in study participants overall by reducing fat and inflammation although not scarring. This medication is not for everyone and may have potential side effects as well. Vitamin E has been linked with a slightly increased risk of heart disease and prostate cancer. Discuss the potential benefits and side effects of vitamin E with your doctor.

Some studies suggest that coffee may benefit the liver by reducing the risk of liver diseases like NAFLD and lowering the chance of scarring. It’s not yet clear how coffee may prevent liver damage. But certain compounds in coffee are thought to lower inflammation and slow scar tissue growth. If you already drink coffee, these results may make you feel better about your morning cup. But if you don’t already drink coffee, this probably isn’t a good reason to start. Discuss the possible benefits of coffee with your health care team.

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease prognosis

Patients with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) have a decreased survival as compared to the general population 110. Individuals with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) exhibit increased mortality rates when compared to the general population 111, 112, 77. People with non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) have a high risk of mortality from cardiovascular causes as these patients have metabolic derangements, followed by cancers and only then liver disease 110, 113, 111, 77. Cardiovascular causes of mortality are higher in non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) patients than liver causes 114, 115. NAFLD patients die 9 times more often from liver disease than the general population 113.

NAFLD is a slowly progressive disease 116, 117; simple faty liver (steatosis) is reversible and non-progressive, whereas nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) can progress to cirrhosis 115. The main risk factors for having advanced liver fibrosis are older age 118, 119, presence of obesity and central obesity 120, as well as type 2 diabetes 121 and hypertension 122. In a 13 year follow-up study by Ekstedt et al 117 the progression of cirrhosis were seen in 41% subjects. These subjects more often had a weight gain exceeding 5 kg, they were more insulin resistant and they exhibited more pronounced hepatic fatty infiltration at follow-up 117. Most NAFLD patients will develop diabetes or impaired glucose tolerance in the long term 117. A meta-analysis on 17 studies done by White et al. 123 showed that in cohorts of NAFLD or NASH with few or no cases of cirrhosis, the risk of developing liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma [HCC]) was minimal at 0 to 3% over a 20 year follow up, and in cohorts with NASH with cirrhosis, the risk was high at 2.4 to 12.8% after 3 to 12 years of follow up. In fact, NAFLD-associated cirrhosis accounts for 15%-30% of cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) 124. Patients with NAFLD can also progress to hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), even without cirrhosis 125. Some cases of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) were reported in patients with simple steatosis, without NASH or fibrosis 126, 127.

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis also called NASH or metabolic dysfunction associated steatohepatitis (MASH) is a fatty liver disease characterized by fatty changes with lobular hepatitis in people who drink little or no history of excessive alcohol consumption 128, 129, 130, 131, 132, 133. Jurgen Ludwig and colleagues in July 1980, at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota, published the first article to identify non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) 128. At the time, steatohepatitis, which is a term to describe an inflammation of the liver that is accompanied by the abnormal accumulation of fat, was thought to be caused by excessive alcohol consumption. But the Mayo study described 20 people with fatty and inflamed livers — none of whom was a heavy alcohol drinker 128. Most had some liver scarring, also known as fibrosis 128. Three of the patients had cirrhosis, liver damage that results from such scarring. The study also noted that “most patients were moderately obese, and many had obesity-associated diseases” 128. Obesity and type 2 diabetes, two conditions associated with insulin resistance, are major risk factors for the development of NASH. Accumulating evidence suggests that the hyperinsulinemia associated with insulin resistance may be important in the pathogenesis of NASH.

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is a severe form of nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) now called metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) a term applied to a liver disease involving the presence of too much fat in the liver cells with or without inflammation and cellular injury that is not caused by alcohol 134, 135. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is the form of NAFLD in which you have inflammation of the liver and liver damage, in addition to fat in your liver. The inflammation and liver damage of NASH may lead to serious liver scarring, called cirrhosis. NASH may progress to cirrhosis, in which the liver is scarred and permanently damaged. Cirrhosis can lead to liver cancer.

Experts guess that about 10% to 24% of Americans have nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and about 1.5% to 6.5% have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) 61, 64.

A diagnosis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is established by the presence of morphologic changes on liver biopsy similar to those seen in alcoholic hepatitis, including hepatocellular fat accumulation, evidence of lobular inflammation and cell injury, and in some cases, progressive fibrosis, but are found in the absence of alcohol abuse. Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is typically identified during the evaluation of elevated ALT (alanine aminotransferase) or AST (aspartate aminotransferase) levels after exclusion of viral, metabolic, and other causes of liver disease.

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is increasingly recognized as a relatively common disorder occurring in 3% of adults that may progress to hepatic fibrosis, a precursor to cirrhosis in 15% to 40% of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) patients 132. Cirrhosis is a condition in which your liver is scarred and permanently damaged. Scar tissue replaces healthy liver tissue and prevents your liver from working normally. Scar tissue also partly blocks the flow of blood through your liver. As cirrhosis gets worse, your liver begins to fail. Exactly how many patients with nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) progress to cirrhosis is unknown, but 1% to 2% of liver transplants are now performed because of a pretransplant diagnosis of nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

If you have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), you may have symptoms that could take years for them to develop. If liver damage from nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) leads to permanent scarring and hardening of your liver, this is called cirrhosis.

Symptoms from nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) may include:

- Severe tiredness

- Weakness

- Weight loss

- Yellowing of the skin or eyes (jaundice)

- Spiderlike blood vessels on your skin

- Long-lasting itchy skin.

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) that turns into cirrhosis could cause symptoms like fluid retention, abdominal swelling (ascites), shortness of breath, swelling of the legs, enlarged spleen, red palms, internal bleeding, muscle wasting, and confusion. People with cirrhosis over time may develop liver failure and need a liver transplant.

If you have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), no medication is available to reverse the fat buildup in your liver. In some cases, the liver damage stops or even reverses itself. But in others, nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) continues to progress. If you have nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), it’s important to control any conditions that may contribute to fatty liver disease.

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) treatments and lifestyle changes may include:

- Losing weight

- Medication to reduce cholesterol or triglycerides

- Medication to reduce blood pressure

- Medication to control diabetes

- Limiting over-the-counter (OTC) drugs

- Avoiding alcohol

- Seeing a liver specialist

Some medications are being studied as possible treatments for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). These include antioxidants like vitamin E. Scientists are also studying some new diabetes medications for nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) that may be given even if you don’t have diabetes. However, you should only take these medicines after consulting with a liver specialist.

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis causes

Scientists don’t know exactly why fat builds up in some livers and not others. They also don’t fully understand why some fatty livers turn into nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) are both linked to the following 77, 78, 79, 80, 81:

- Genetics. Researchers have found that certain genes may make you more likely to develop NAFLD. These genes may help explain why NAFLD is more common in certain racial and ethnic groups. Studies have identified many genetic changes that may be associated with the development of NAFLD and NASH. Among these is a particular variation in the PNPLA3 gene 82. The PNPLA3 gene provides instructions for making a protein called adiponutrin, which is found in fat cells (adipocytes) and liver cells (hepatocytes). The function of this protein is not well understood, but it is thought to help regulate the production and breakdown of fats (lipogenesis and lipolysis) and the development of adipocytes. Studies indicate that the activity (expression) of the PNPLA3 gene decreases during periods without food (fasting) and increases after eating, suggesting that the amount of adiponutrin protein produced is regulated as needed to help process and store fats in the diet. The PNPLA3 gene variation associated with NAFLD is thought to lead to increased production and decreased breakdown of fats in the liver. Research is ongoing to determine how this and other genetic changes contribute to the development of NAFLD and its complications.

- Overweight or obesity.

- Insulin resistance, which happens when your cells don’t take up sugar in response to the hormone insulin.

- Type 2 diabetes, sometimes called high blood sugar or hyperglycemia.

- High levels of fats (abnormal levels of cholesterol—high total cholesterol, high LDL cholesterol, or low HDL cholesterol), especially triglycerides, in the blood.

These combined health problems may contribute to a fatty liver. However, some people get NAFLD even if they do not have any risk factors.

Risk factors for developing nonalcoholic steatohepatitis

Many diseases and health problems can increase your risk of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), including:

- Family history of fatty liver disease or obesity.

- Growth hormone deficiency, which means the body doesn’t make enough hormones to grow.

- High cholesterol.

- High levels of triglycerides in the blood.

- Insulin resistance.

- Metabolic syndrome. Metabolic syndrome is a group of traits and medical conditions linked to overweight and obesity. Doctors define metabolic syndrome as the presence of any three of the following:

- large waist size

- high levels of triglycerides in your blood

- low levels of HDL cholesterol in your blood

- high blood pressure

- higher than normal blood glucose levels or a diagnosis of type 2 diabetes

- Obesity, especially when fat is centered in the waist.

- Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

- Obstructive sleep apnea.

- Type 2 diabetes.

- Underactive thyroid, also called hypothyroidism.

- Underactive pituitary gland, or hypopituitarism.

If you have risks for NAFLD and also drink alcohol excessively, you could have both NAFLD and alcohol-associated liver disease at the same time. No tests can easily tell how much each plays a role.

Nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH) is more likely in these groups:

- People older than 50.

- People with certain genetic risk factors.

- People with obesity.

- People with diabetes or high blood sugar.