Frey’s syndrome

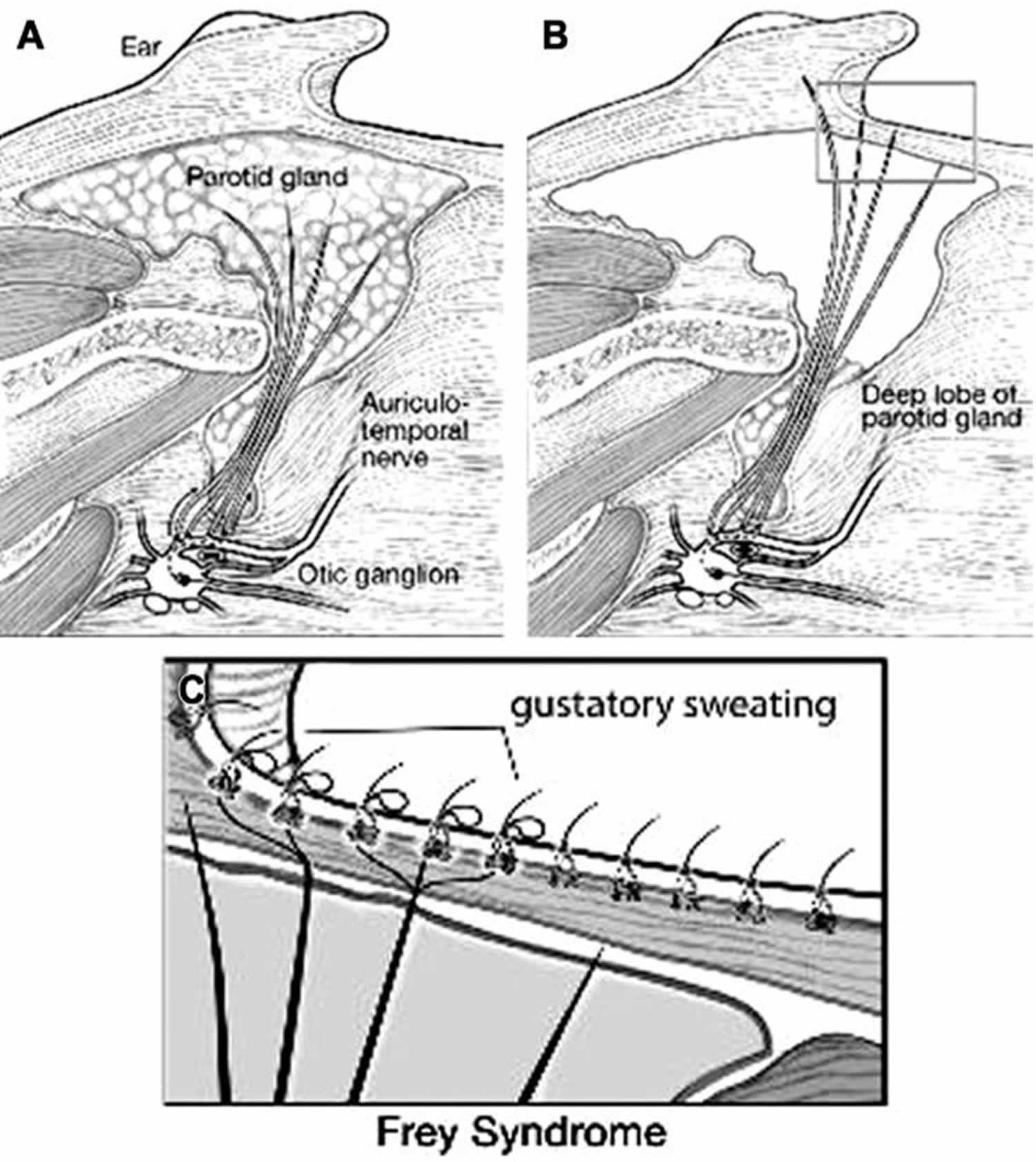

Frey’s syndrome also called auriculotemporal syndrome is a rare, neurological disorder that causes a person to sweat excessively and flushing in the preauricular area while eating 1. Frey’s syndrome most often occurs as a complication of surgery involving the parotid gland (a major salivary gland located below the ear). Frey’s syndrome may also occur following neck dissection, facelift procedures, or trauma to the area near the parotid gland 2. Symptoms usually develop within several months of the procedure or trauma, but may develop several years later 3. The main symptoms include flushing and excessive sweating (hyperhidrosis) on the cheek, temple, or behind the ear, when eating or thinking about food (gustatory sweating) 2. Some people with Frey’s syndrome may experience a burning sensation, itching, or pain around the affected area 2. The symptoms are usually mild but can be severe, causing significant discomfort or social anxiety 2.

Frey’s syndrome is thought to be caused by damage to both the nerves that regulate the sweat glands, and the nerves that regulate the parotid glands 3. It is believed that the damaged nerves regrow abnormally and connect to the wrong glands 3. Frey’s syndrome is diagnosed based on medical history (e.g. a history of surgery or trauma) and symptoms. The diagnosis can be confirmed with a test called the Minor’s starch-iodine test 2.

The exact incidence of Frey’s syndrome is unknown. Frey’s syndrome most often occurs as a complication of the surgical removal of a parotid gland (parotidectomy). The percentage of individuals who develop Frey syndrome after a parotidectomy is controversial and reported estimates range from 30-50 percent. In follow-up examinations, approximately 15 percent of affected individuals rated their symptoms as severe. Frey’s syndrome affects males and females in equal numbers 3.

Treatment, when needed, is focused on controlling the symptoms and often involves injections of botulinum toxin A (Botox) and/or topical antiperspirants 2. Repeat Botox injections are often needed as symptoms return, which occurs yearly on average 2. Of note, although Botox injections have been reported to improve symptoms and quality of life, no randomized controlled trials of its use to treat Frey’s syndrome have been documented 3.

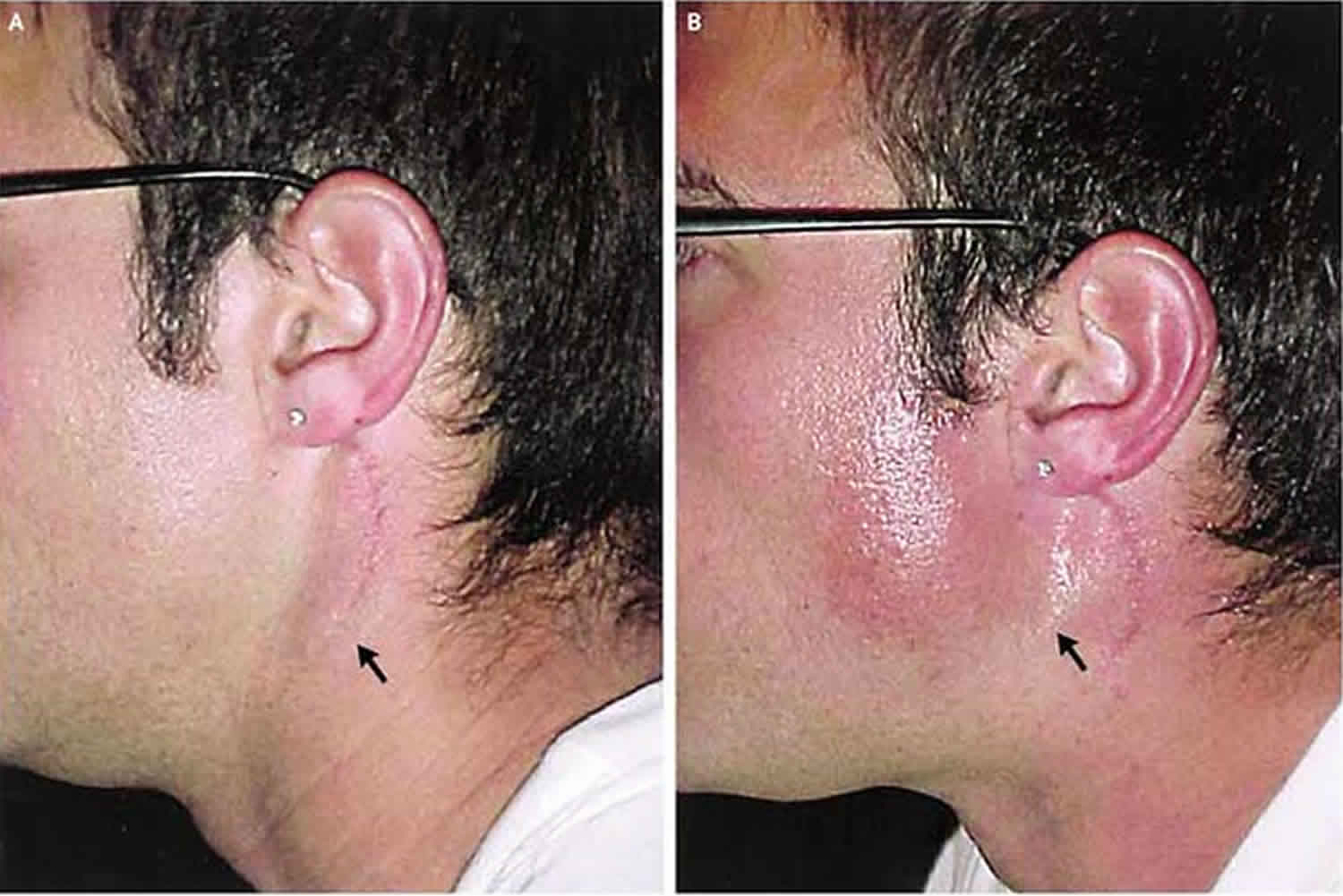

Figure 1. Frey’s syndrome cause

Footnote: (A) Normal innervation of the parotid gland by the postganglionic parasympathetic nerve fibers from the auriculotemporal nerve. (B) Postoperative diagram depicting the regenerated postganglionic parasympathetic nerve fibers extending to the overlying cutaneous tissue. (C) Postganglionic parasympathetic nerve fibers innervating the cutaneous sweat gland that results in gustatory sweating.

[Source 2 ]Frey’s syndrome cause

The exact underlying cause of Frey’s syndrome is not completely understood. The most widely held theory is that Frey syndrome results from simultaneous damage to sympathetic and parasympathetic nerves in the region of the face or neck near the parotid glands. Parasympathetic nerves are part of the autonomic nervous system, which is the portion of the nerve system that controls or regulates involuntary body functions (i.e., those functions that occur without instruction from the conscious mind). One function of parasympathetic nerves is to regulate the activity of glands including the parotid glands, but not the sweat glands. Sweat glands and blood vessels throughout the body are controlled by sympathetic fibers.

In Frey’s syndrome, researchers believe that the parasympathetic and sympathetic nerves near the parotid glands are cut, especially tiny branches originating from the auriculotemporal nerve. The auriculotemporal nerve supplies nerves (innervates) to certain structures in the face including the parotid glands.

Normally, damaged nerve fiber(s) eventually heal themselves (regenerate). In Frey’s syndrome, it is believed that damaged nerve fibers regenerate abnormally by growing along the sympathetic fiber pathways, ultimately connecting to the miniscule sweat glands found along the skin. Therefore, the parasympathetic nerves that normally tell the parotid glands to produce saliva in response to tasting food now respond by instructing the sweat glands to produce sweat and the blood vessels to widen (dilate). The cumulative result is excessive sweating and flushing when eating certain foods.

Damage to the nerves in the parotid gland region of the face may occur for several different reasons including as a complication of surgery or blunt trauma to the side of the face. In older reports, infections of the parotid glands were suspected, but a detailed examination always points to a surgical drainage of a parotid abscess. The most common reported cause of Frey’s syndrome is a surgical procedure called a parotidectomy (the surgical removal of a parotid gland). Although the exact percentage is not agreed upon in the medical literature, some sources suggest that more than half of all individuals who undergo a parotidectomy eventually develop Frey’s syndrome. A recent meta-analysis concluded that the interposition of tissue after parotidectomy might decrease the incidence of Frey syndrome after parotidectomy.

Another rarely described cause (etiology) of Frey’s syndrome is damage to the main sympathetic nerve chain in the neck.

In extremely rare cases, Frey’s syndrome has been described in newborns, possibly following trauma due to delivery with forceps. Actual careful examination reveals that the principal symptom is flushing which might be physiologic at a younger age. The key symptom of facial sweating is not emphasized in newborns rising doubts about the correctness of these observations.

Frey’s’s syndrome prevention

Prevention of Frey’s syndrome has been guided by the alteration of surgical techniques or the addition of procedures focused on preventing synkinesis 2. The overarching theme for the surgical prevention of Frey’s syndrome has been the incorporation and maintenance of a barrier between the underlying postganglionic parasympathetic nerve endings within the transected parotid and the overlying cutaneous tissue. Many techniques aimed at accomplishing this have been described and include increased skin flap thickness, local fascia or muscle flaps, and the use of acellular dermal matrix or free fat grafts 2.

Increased skin flap thickness

Within the facial skin, the sweat glands are positioned at the same level or slightly deeper than the base of the hair follicles. Based on this, it has been presumed that increasing the thickness of the elevated skin flap, to keep the sweat glands from being exposed, affords protection from the aberrant parasympathetic nerve regeneration that results in Frey’s syndrome. Early studies suggested that there was a significant increase in the rate of Frey’s syndrome when a thin flap was elevated compared with that of a thick flap (12.5 vs 2.6%) 4. Although this study did lay a foundation for surgical technique, its measurements for flap thickness were crude, and the diagnosis of Frey’s syndrome lacked objective measurements 4.

More recent studies, which objectively measured flap thickness and assessed Frey’s syndrome by clinical symptoms as well as starch-iodine testing, have failed to demonstrate a reduction in the incidence of Frey’s syndrome with increased flap thickness 5. Although flap thickness did not decrease the incidence of Frey’s syndrome in these studies, it did show a decrease in the total skin surface area affected and perhaps the overall severity of the disease 5.

Transposition muscle or fascia flaps

Similar to increasing the thickness of the elevated skin flap to shield the facial sweat glands from aberrant reinnervation, pedicled muscle and fascia flaps have been used to cover the resected parotid gland in an attempt to create a physical barrier between the overlying dermis and the transected nerve fibers within the parotid.

Temporoparietal fascia flap

The temporoparietal fascia flap is a broad, vascularized fascia flap that is based off the superficial temporal artery. It was first described as a composite flap for ear reconstruction in 1976 by Fox and Edgerton 6 and was later adapted to a fascia flap. Given its accessibility, predictable vasculature, and low donor site morbidity, it became a common method for reconstruction of the cheek, ear, nasal cavity, and orbit.

The use of a temporoparietal fascia flap was first described in a series of 7 patients undergoing parotidectomy for the prevention of Frey’s syndrome in 1995 by Sultan and colleagues 7. The results of this series showed that prophylactic inlay of a temporoparietal fascia flap to the parotidectomy defect prevented Frey’s syndrome as assessed by both clinical history and starch-iodine testing in all 7 patients. In addition, the temporoparietal fascia flap allowed for improved cosmetic outcome because it reduced the contour defect 7. Since its initial description, multiple retrospective studies have confirmed the utility of temporoparietal fascia flap for the prevention of Frey’s syndrome. In these studies, the use of a temporoparietal fascia flap decreased the rate of Frey’s syndrome after parotid surgery, as determined by positive starch-iodine test, to 4% to 17%, and reduced the clinical incidence of gustatory sweating to 4% to 8% 8. This reduced clinical incidence compared with 39% to 57% and 34% to 43%, respectively, for patients who did not undergo temporoparietal fascia flap reconstruction 8.

Although this represents an effective technique for the prevention of Frey’s syndrome, it does require an extended incision, which can generally be hidden in the hairline. In addition, the course of the temporal branch of the facial nerve is at potential risk for injury. Moreover, local flaps increase operative time and can require a second reconstructive team, which may increase overall cost of the procedure.

Sternocleidomastoid muscle flap

The sternocleidomastoid muscles flap is a muscular flap with a tripartite blood supply. The occipital artery, which enters the posterior surface of the muscle in the upper third, is the predominant blood supply to the superior sternocleidomastoid flap. This technique has been favored for reconstruction secondary to its proximity and ability to easily rotate into a parotidectomy defect. Although the sternocleidomastoid flap is easy to harvest and can provide adequate cosmetic reconstruction, its ability to prevent Frey’s syndrome after parotidectomy is unclear. Reports in the literature have supported that the use of an sternocleidomastoid muscle flap decreases the incidence of Frey’s syndrome. In a retrospective study of 43 patients, Filho and colleagues 9 demonstrated that sternocleidomastoid muscle flap reconstruction following parotidectomy resulted in no cases of Frey’s syndrome in 24 patients, when assessed clinically and by starch-iodine testing, comparing with 52.6% and 63.2%, respectively, in a control group of patients not undergoing sternocleidomastoid flap reconstruction 9. In addition, a meta-analysis published in 2009 by Curry and colleagues 10 concluded that sternocleidomastoid flaps decrease the rate of Frey’s syndrome after parotidectomy. However, other studies have shown that the muscle flaps are ineffective at preventing the sequela of Frey’s syndrome 11. Unfortunately, given the relatively small number of patients evaluated in the studies and the immense heterogeneity between studies, it is difficult to draw conclusions based on the data available 11.

Superficial musculoaponeurotic system flap

Another technique, focused on creating a physical barrier between the underlying regenerating auriculotemporal nerve fibers and the overlying dermis, is a superficial musculoaponeurotic system flap. This superficial musculoaponeurotic system flap can be harvested using a standard modified Blair incision or the facelift incision, and the superficial musculoaponeurotic system can be easily separated from the overlying skin and the parotid tissue to be tightly plicated to the ear perichondrium and the sternocleidomastoid muscle, creating a tight surface that prevents the retromandibular collapse for improved contouring. Similar to the other types of local reconstruction, the efficacy data are mixed. Bonanno and colleagues 12 found this technique overwhelmingly effective in preventing the development of Frey’s syndrome, while other groups failed to demonstrate its ability to do so 13. However, although the incidence of postparotidectomy Frey’s syndrome was not significantly changed in these studies, the severity and overall surface area affected were significantly less 14. Although this technique does serve to isolate the underlying regenerating nerve fibers, it is more commonly used in clinical practice for cosmetic reasons rather the prevention of Frey’s syndrome.

Biomaterial and autologous implantation

Autologous and biosynthetic material have been used to create the physical barrier between the transected parotid and the overlying cutaneous tissues. Numerous products have been reported, but the most commonly cited are acellular dermal matrix implantation and autologous fat grafting.

Acellular dermal matrix

Acellular dermal matrix is a soft tissue matrix graft that is generated by decellularization of tissue that results an intact extracellular matrix. It is commonly used in wound healing and reconstructive surgery because it provides a scaffold for regenerating tissues. Since its development, it has been used in parotidectomy for the prevention of Frey’s syndrome. As with muscle or fascia flaps, the goal of this graft is to create a biologic barrier between the facial skin flap and the transected parotid gland. In a limited number of studies that have investigated its effectiveness at preventing Frey’s syndrome, there are limited data that suggest it is effective in reducing both objective and clinical measures of Frey’s syndrome 15.

Abdominal fat grafting

Abdominal fat implantation to the parotidectomy defect is a commonly used technique for decreasing the postsurgical defect and improving cosmesis. In very limited studies, there have been reports that abdominal fat implantation decreases the occurrence of Frey’s syndrome. However, this has failed to be substantiated. In addition, abdominal fat harvest requires an additional incision on the abdomen and can frequently be complicated by donor site hematoma and surgical site seroma.

Frey’s syndrome symptoms

The symptoms of Frey syndrome can include flushing, sweating, burning, neuralgia, and itching. The symptoms of Frey syndrome typically develop within the first year after surgery in the area near the parotid glands. In some cases, Frey syndrome may not develop until several years after surgery. The characteristic symptom of Frey’s syndrome is gustatory sweating, which is excessive sweating on the cheek, forehead, and around the ears shortly after eating certain foods, specifically foods that produce a strong salivary response such as sour, spicy or salty foods. Generally, the symptoms are mild but can result in discomfort as well as social anxiety and avoidance.

Additional symptoms that may be associated with Frey’s syndrome include flushing and warmth in the affected areas. This is rarely an important complaint.

While other symptoms have been associated with Frey’s syndrome, they are probably unrelated. Pain is sometimes described, but it is probably more related to the surgery than actually to Frey syndrome. The specific area affected, the size of the area, and the degree of sweating and flushing vary greatly among affected individuals. In some patients, symptoms may be mild and affected individuals may not be bothered by the symptoms. In other cases, such as those that experience profuse sweating, affected individuals may require therapy.

Frey’s syndrome diagnosis

A diagnosis of Frey’s syndrome is made based upon identification of characteristic symptoms, a detailed patient history, a thorough clinical evaluation and a specialized test called the Minor Iodine-Starch Test. During the Minor Iodine-Starch Test, an iodine solution is applied to patient’s postsurgical affected areas of the face. Once dry, a starch powder such as corn starch is applied over the iodine solution. Individuals are then given an oral stimulus usually a highly acidic food such as a lemon wedge. In affected individuals, discoloration (turns blue/brown usually purple) due to excessive sweating occurs on the affected areas. Patients who underwent parotidectomy had a positive Minor starch-iodine test in 62% of cases, whereas the self-reported incidence of symptoms was only 23% in the same group 16. These numbers attest both to the high incidence of the synkinesis and to the subclinical nature of Frey syndrome.

Figure 2. Frey’s syndrome diagnosis (starch-iodine test)

Frey’s syndrome treatment

Although Frey’s syndrome can be mild and well-tolerated, in some individuals, it can cause excessive discomfort. Treatment is symptomatic and directed toward relief of symptoms. Until recently, most treatment measures have generally been unsatisfactory. Treatment options include drug therapy or surgery.

Topical application of drugs that block certain activities of the nervous system (anticholinergics) or drugs that hinder sweating (antihidrotics) have been used. Surgical removal (excision) of the affected skin and the insertion (interposition) of new tissue to the affected area (muscle flaps) has been described, but are considered risky because of the presence of facial nerve fibers right below the skin after parotidectomy.

In the last decade botulinum A toxin has become established as a therapy for individuals with bothersome Frey’s syndrome 17. The therapy consists of local injections of botulinum A toxin in the affected skin. Initial results have demonstrated that this therapy results in the suppression of sweating and causes no significant side effects 18. Another advantage of botulinum A toxin is that it is minimally invasive compared to other therapies. As in other indications, the effect of botulinum toxin is not permanent, lasting on average about 9-12 months.

Unfortunately, with botulinum toxin A injection, symptomatic recurrence has been demonstrated in up to 27% and 92% of patients at 1 and 3 years, respectively 19. However, despite a high rate of return symptoms after botulinum toxin A injection, repeat botulinum toxin A injection has been shown to be effective 19. For the studies investigating botulinum toxin A, the injection dose was between 1.9 and 2.5 U/cm² in the involved area 17. Unfortunately, no randomized control studies have been documented, and based on a Cochrane Review of the literature, no conclusions can be made on its efficacy 20.

Surgical management

Historically, surgical treatment of Frey’s syndrome has not been used. Reports of surgical transection of the auriculotemporal nerve, tympanic nerve, and greater auricular nerve have been described for the management of Frey’s syndrome, but they are not commonly practiced. Recently, a cohort of 17 patients with postparotidectomy Frey syndrome who underwent both sternocleidomastoid and temporalis fascia transposition was reported by Dia and colleagues 21. This report demonstrated that greater than 50% (9/17) of patients who underwent the transposition procedure had complete resolution by starch-iodine testing 21. In addition, there was a significant reduction in the average surface area of gustatory-sweating–positive skin from 12.80 to 1.32 cm² in all patients postoperatively 21. Although this method is compelling and does appear to be a feasible option for surgical management of Frey’s syndrome, it does have an increased risk for facial nerve injury. Given the limited number of studies on transposition procedures, no recommendations can be made on its evidence-based efficacy. However, if surgery for Frey’s syndrome is to be attempted, it should be only be used in cases that are refractory to conservative nonsurgical measures.

References- Frey L. Le syndrome du nerf auriculo-temporal. Revue Neurologique. 1923;2:92–104.

- Motz KM, Kim YJ. Auriculotemporal Syndrome (Frey Syndrome). Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2016;49(2):501–509. doi:10.1016/j.otc.2015.10.010 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5457802

- Frey syndrome. https://rarediseases.org/rare-diseases/frey-syndrome

- Singleton G, Cassisi N. Frey’s syndrome: incidence related to skin flap thickness in parotidectomy. Laryngoscope. 1980;90:1636–40.

- Durgut O, Basut O, Demir U, et al. Association between skin flap thickness and Frey’s syndrome in parotid surgery. Head Neck. 2012;35(12):1781–6.

- Fox J, Edgerton M. The fan flap: an adjunct to ear reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1976;58:663–7.

- Sultan M, Wider T, Hugo N. Frey’s syndrome: prevention with the temporopartietal fascial flap interposition. Ann Plast Surg. 1995;34:292–7.

- Ahmen O, Kolhe P. Prevention of Frey’s syndrome and volume deficit after parotidectomy using the superficial temporal artery fascial flap. Br J Plast Surg. 1999;52:256–60.

- Filho W, Dedivitis R, Rapoport A, et al. Sternocleidomastoid muscle flap preventing Frey syndrome following parotidectomy. World J Surg. 2004;28:361–4.

- Curry J, King N, Reiter D, et al. Meta-analysis of surgical techniques for preventing parotidectomy sequelae. Arch Facial Plast Surg. 2009;11(5):327–31.

- Sanabria A, Kowalski L, Bradley P, et al. Sternocleidomastoid muscle flap in preventing Frey’s syndrome after parotidectomy: a systematic review. Head Neck. 2012;34(4):589–98.

- Bonanno P, Palaia D, Rosenberg M, et al. Prophylaxis against Frey’s syndrome in parotid surgery. Ann Plast Surg. 2000;44:498–550.

- Wille-Bischofberger A, Rajan G, Linder T, et al. Impact of the SMAS on Frey’s syndrome after parotid surgery: a prospective, long-term study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;120:1519–23.

- Barbera R, Castillo F, D’oleo C, et al. Superficial musculoaponeurotic system flap in partial parotidectomy and clinical and subclinical Frey’s syndrome. Cosmesis and quality of life. Head Neck. 2014;36(1):130–6.

- Wang W, Fan J, Sun C, et al. Systemic evaluation on the use of acellular matrix graft in prevention of Frey syndrome after parotid neoplasm surgery. J Craniofac Surg. 2013;24:1526–9.

- Neumann A, Rosenberger D, Vorsprach O, et al. The incidence of Frey syndrome following parotidectomy: results of a survey and follow-up. HNO. 2011;2:173–8.

- Beerens A, Snow G. Botulinum toxin A in the treatment of patients with Frey syndrome. Br J Surg. 2002;89(1):116–9.

- Tugnoli V, Marchese Ragona R, Eleopra R, et al. The role of gustatory flushing in Frey’s syndrome and its treatment with botulinum toxin type A. Clin Auton Res. 2002;12(3):174–8.

- Laccourreye O, Akl E, Gutierrez-Fonseca R, et al. Recurrent gustatory sweating (Frey’s syndrome) after intracutaneous injection of botulinum toxin type A: incidence, management, and outcome. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(3):283–6.

- Li C, Wu F, Zhang Q, et al. Interventions for the treatment of Frey’s syndrome. Co-chrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(3):CD009959

- Dia X, Liu H, He J, et al. Treatment of postparotidectomy Frey syndrome with the interposition of temporalis fascia and sternocleidomastoid flaps. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119(5):514–21.