What is hyperkeratosis

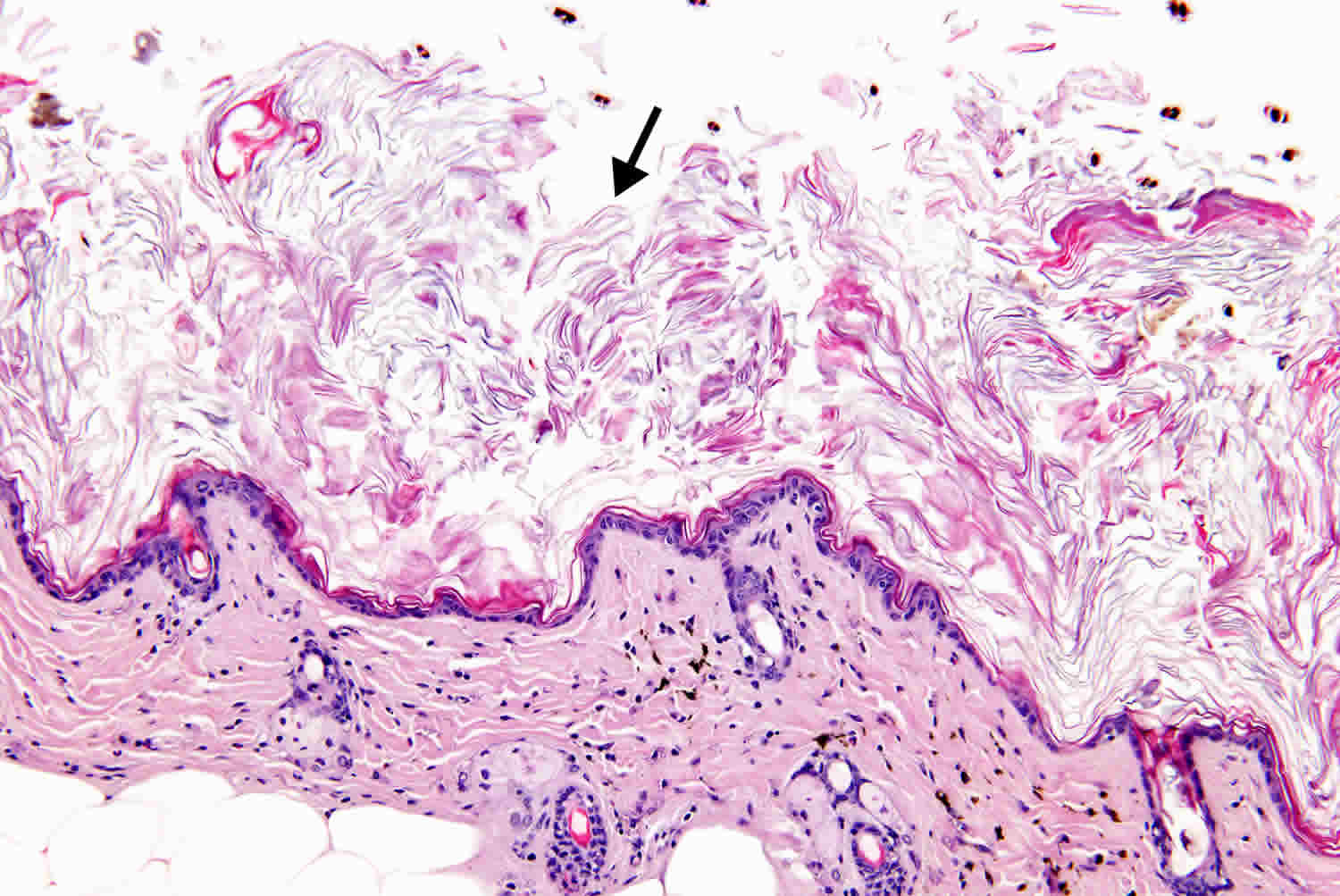

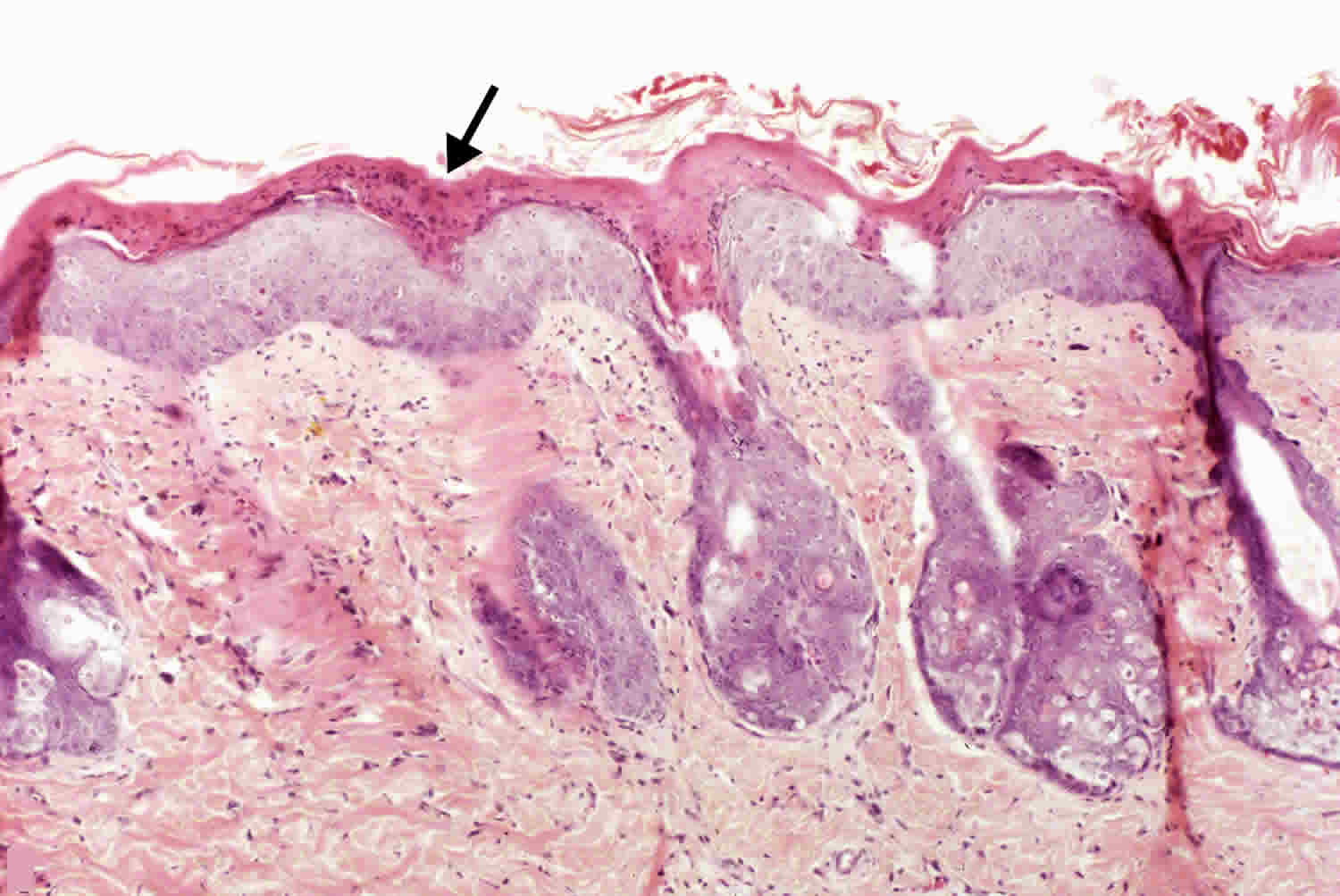

Hyperkeratosis also called excessive keratinization or scaling, is an umbrella term that describes an abnormal thickening of the stratum corneum, the outermost layer of your skin, often associated with the presence of an abnormal quantity of keratin and is also usually accompanied by an increase in the granular layer of the skin (see Figures 4 and 5) 1. As the stratum corneum layer normally varies greatly in thickness across different sites, some experience is needed to assess minor degrees of hyperkeratosis 2. Hyperkeratosis or thickening of the stratum corneum, occurs in two forms: orthokeratotic or parakeratotic hyperkeratosis. In orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis sometimes referred to as orthokeratosis, the dead keratinocytes are anuclear (see Figure 2), whereas in parakeratotic hyperkeratosis sometimes referred to as parakeratosis, the dead keratinocytes have retained pyknotic nuclei (see Figure 3). Hyperkeratosis is most commonly orthokeratotic or thickening of the cornified layer without retained nuclei (see Figure 2). Parakeratotic hyperkeratosis, which is characterized by the presence of nuclei in the cornified layer, occurs rarely and is usually concurrent with epithelial hyperplasia (see Figure 3).

Hyperkeratosis is an umbrella term for a number of skin conditions. It involves a thickening of the stratum corneum (the outer layer of the skin), often associated with a keratin abnormality, .

Hyperkeratosis often accompanies squamous epithelial hyperplasia. Forms of hyperkeratosis may include warts, corns, and calluses. Pressure-related hyperkeratosis occurs as a result of excessive pressure, inflammation or irritation to the skin. When this happens, the skin responds by producing extra layers of keratin to protect the damaged areas of skin.

In general, hyperkeratosis associated with hyperplasia of the underlying squamous epithelium is not diagnosed separately but is described in the pathology narrative as a component of the hyperplasia. However, if the hyperkeratosis is prominent or is disproportionately increased compared with the degree of hyperplasia, or if it occurs in the absence of epithelial hyperplasia, then it should be diagnosed and graded. Grading should be based on the thickness of the keratin and the amount of tongue surface affected. The pathologist should use his or her judgment in determining whether or not the hyperkeratosis should be diagnosed separately. When diagnosed, the term “hyperkeratosis” should be used for both the ortho- and parakeratotic forms (i.e., do not use the term parakeratosis).

Although the symptoms of all types of hyperkeratosis can be difficult and uncomfortable, the disease can be successfully managed. Hyperkeratotic skin disorders are characterised by red, dry cracked and scaling skin affecting 10–20% of the Western population. While the rate of incidence of hyperkeratotic condition increases with age, different types affect persons of all ages, gender and racial/ethnic groups.

A variety of treatment options exists for hyperkeratosis, including keratolytics, moisturisers and corticosteroids that promote skin hydration and promote an increased lipid content in the stratum corneum. Emollients and moisturisers are frequently used to disrupt the cycle of skin dryness and other skin barrier disorders.

Figure 1. Skin anatomy

Figure 2. Orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis

Figure 3. Parakeratotic hyperkeratosis

Figure 4. Hyperkeratosis feet

Figure 5. Hyperkeratosis hands

Hyperkeratosis causes

Hyperkeratosis or skin thickening is often the skin’s normal protection against rubbing, pressure and other forms of irritation, causing calluses and corns on the hands and feet or whitish areas inside the mouth 3. Other forms of hyperkeratosis occur as part of the skin’s defence against chronic inflammation, infection and the radiation of sunlight or irritating chemicals. Less often, hyperkeratosis develops on skin that has not been irritated. These types may be part of an inherited condition, may begin soon after birth and can affect skin on large areas of the body 4.

Hereditary hyperkeratosis

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is also known as ‘bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma’, ‘bullous ichthyosiform erythroderma’, or ‘bullous congenital ichthyosiform erythroderma Brocq’ , is a rare skin disorder of the ichthyosis family that is present at birth affecting around 1 in 200,000 to 300,000 people worldwide. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis involves the clumping of keratin filaments 4. At birth, the skin of the individual is entirely covered with thick, horny, armourlike plates that are soon shed, leaving a raw surface on which scales then reform. Affected babies may have very red skin (erythroderma), hyperkeratosis and severe blisters. Because newborns with this disorder are missing the protection provided by normal skin, they are at risk of becoming dehydrated and developing infections in the skin or throughout the body (sepsis).

As affected individuals get older, blistering is less frequent, erythroderma becomes less evident, and the skin becomes thick (hyperkeratotic), especially over joints, on areas of skin that come into contact with each other, or on the scalp or neck. This thickened skin is usually darker than normal. Bacteria can grow in the thick skin, often causing a distinct odor.

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis can be categorized into two types. People with PS-type epidermolytic hyperkeratosis have thick skin on the palms of their hands and soles of their feet (palmoplantar or palm/sole hyperkeratosis) in addition to other areas of the body. People with the other type, NPS-type, do not have extensive palmoplantar hyperkeratosis but do have hyperkeratosis on other areas of the body.

Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is part of a group of conditions called ichthyoses, which refers to the scaly skin seen in individuals with related disorders. However, in epidermolytic hyperkeratosis, the skin is thick but not scaly as in some of the other conditions in the group.

Mutations in the KRT1 or KRT10 genes are responsible for epidermolytic hyperkeratosis. These genes provide instructions for making proteins called keratin 1 and keratin 10, which are found in cells called keratinocytes in the outer layer of the skin (the epidermis). The tough, fibrous keratin proteins attach to each other and form fibers called intermediate filaments, which form networks and provide strength and resiliency to the epidermis.

Mutations in the KRT1 or KRT10 genes lead to changes in the keratin proteins, preventing them from forming strong, stable intermediate filament networks within cells. Without a strong network, keratinocytes become fragile and are easily damaged, which can lead to blistering in response to friction or mild trauma. It is unclear how these mutations cause the overgrowth of epidermal cells that results in hyperkeratotic skin.

KRT1 gene mutations are associated with PS-type epidermal hyperkeratosis, and KRT10 gene mutations are usually associated with NPS-type. The keratin 1 protein is present in the keratinocytes of the skin on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet as well as other parts of the body, so mutations in the KRT1 gene lead to skin problems in these areas. The keratin 10 protein is not found in the skin of the palms and soles, so these areas are unaffected by mutations in the KRT10 gene.

Multiple minute digitate hyperkeratoses

Multiple minute digitate hyperkeratoses is a rare familial or acquired cutaneous eruption of filiform keratosis, typically found across the trunk and extremities. Histopathology, distribution and history can distinguish it from other digitate keratoses. Goldstein 5 described the first case of multiple minute digitate hyperkeratoses in 1967, suggesting the term ‘multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis’ because the projections were numerous, and finger-like, comprising a horn of dense orthokeratin. Multiple minute digitate hyperkeratoses presents with numerous digitate keratoses across the trunk and limbs, with sparing of the face, palms, and soles. The keratoses are skin-coloured, rod-shaped, non-follicular, between 1–5mm in length, between 0.3–2mm in diameter, and arise from otherwise normal skin 6.

Focal acral hyperkeratosis

Focal acral hyperkeratosis is also known as ‘acrokeratoelastoidosis lichenoides’, this condition is a late-onset keratoderma, inherited as an autosomal dominant condition (single parental gene), characterised by oval or polygonal crateriform papules developing along the border of the hands, feet and wrist 4.

Lamellar ichthyosis

Lamellar ichthyosis is a rare skin condition that appears at birth and continues throughout a person’s life. It is passed down through families and both parents must have at least one abnormal gene to pass it on to their children. People with this condition are born with a collodian membrane — a shiny, waxy layer of skin that sheds within the first two weeks of life. Red, scaly skin remains underneath — this resembles the surface of a fish 7.

X-linked ichthyosis

X-linked ichthyosis is also known as ‘steroid sulfatase deficiency’, as well as ‘X-linked recessive ichthyosis’ (from the Ancient Greek ‘ichthys’, meaning ‘fish’) and is a skin condition caused by the hereditary deficiency of the steroid sulfatase (STS) enzyme, affecting between one in 2,000 and one in 6,000 males. X-linked ichthyosis manifests with dry, scaly skin and is due to deletions or mutations in the STS gene. X-linked ichthyosis can also occur in the context of larger deletions, causing contiguous gene syndromes. Treatment is largely aimed at alleviating the skin symptoms 8.

Keratosis pilaris

Keratosis pilaris also known as ‘follicular keratosis’, keratosis pilaris is a common, autosomal dominant, genetic follicular condition that is manifested by the appearance of rough bumps on the skin. It most often appears on the back and outer sides of the upper arms (although the lower arms can also be affected), and can occur on any body part except glabrous skin (naturally hairless, such as the palms or soles of the feet). Less commonly, lesions appear on the face, which may be mistaken for acne. This condition has been shown in several small-scale studies to respond well to supplementation with vitamins and fats rich in essential fatty acids. Some research suggests this is due mainly to vitamins E and B. Vitamin A is also thought to be connected to the pathology 9.

Site specific hyperkeratosis

Plantar hyperkeratosis

Plantar hyperkeratosis is a circumscribed keratotic area which may or may not be associated with a hammered great toe. Keratosis often resembles verruca plantaris, for which it is mistakenly treated, until the keratosis breaks down and ulcerates or leaves a permanent scar. Although keratosis under the first metatarsal head is common, it is more usual to have disabling symptoms underneath the middle three metatarsals 10.

Hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola

Hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola is an uncommon benign, asymptomatic, acquired condition of unknown pathogenesis.

Hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola is characterized by hyperpigmented, verrucous or filiform, keratotic thickening of the nipple and/or areola, with a papillomatosis or velvety sensation to touch. Hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola has classically been classified into the following three subsets 11:

- Type I – hyperkeratosis of the nipple and/or areola due to the extension of an epidermal nevus

- Type II – hyperkeratosis of the nipple and/or areola in conjunction with disseminated dermatoses

- Type III – Nevoid hyperkeratosis of the nipple and/or areola

Perez-Izquierdo et al 12 suggested an alternative classification, distinguishing two types: (1) those that are idiopathic or nevoid and (2) those that are secondary to other conditions. Others have advocated that the term “nevoid” be replaced by “idiopathic” 13. Upon review of the literature, a recommended classification is into (1) primary hyperkeratosis of the nipple and/or areola, which is idiopathic 14 and (2) secondary hyperkeratosis of the nipple and/or areola, which is associated with the following:

- Epidermal nevus

- Organoid nevus 15

- Leiomyomas 16

- Verruca 17

- Congenital, acquired, or erythrodermic ichthyosis

- Malignant acanthosis nigricans 18

- Darier disease 19

- Chronic eczema such as atopic dermatitis

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma 20

- Chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis 21

- Pregnant females

- Males receiving hormonal therapy for prostate cancer 22

- Estrogen therapy for androgen insensitivity syndrome 23

- Vemurafenib treatment 24

- Malassezia furfur infection 25

Lichen planus

Lichen planus may appear as a lacy, white patch on the inside of the mouth or as an itchy, violet, scaly patch elsewhere on the skin. In some cases, it affects the mouth, genitals, hair, nails, and rarely, other parts of the body. About one in 50 people develop lichen planus and it occurs equally in men and women. More than two-thirds of cases occur in people aged 30–60 years, however, it can occur at any age. It is not an inherited disease, nor is it an infection, and the rash cannot be caught or passed on to others. Although the cause of this condition is unknown, researchers suspect that it may be related to an abnormal reaction of the immune system. One theory is that the immune system may be triggered by a virus or other factor in the environment to attack cells in the skin, which leads to the inflammation 26.

Seborrheic keratosis

Seborrheic keratosis are small, non-cancerous skin growths. They can be tan, brown or black and are found on the face, trunk, arms or legs. These are very common and most people develop between one and 20 during their lifetime. Their cause is unknown 4.

Corns

Corn is a small area of skin which has become thickened due to the pressure exerted on it. They are roughly round in shape and press into the deeper layers of skin, becoming painful. Hard corns commonly occur on the top of the smaller toes or on the outer side of the little toe. These are the areas where poorly fitted shoes tend to rub the most. Soft corns sometimes form in between the toes, most commonly between the fourth and fifth toes. These are softer because the sweat between the toes keeps them moist. Soft corns can sometimes become infected 27.

Calluses

A callus is larger, broader and has a less well-defined edge than a corn. These tend to form on the underside of the foot (the sole). They commonly form over the bony area just underneath the toes. This area takes much of your weight when you walk. They are usually painless but can become painful 27.

Other

Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans

Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans also known as Flegel disease, hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans is a cutaneous condition characterised by rough, yellow-brown keratotic, flat-topped papules of irregular outline measuring 1–5mm in diameter and up to 1mm in depth 28. Lesions are located primarily on the dorsal feet and lower legs, with a decreasing likelihood of manifestation proximally. Most cases have been reported in Europe. No instigating factor has been identified clearly, however, some investigators have implicated ultraviolet light 29.

Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans , described by Flegel in 1958, is considered to be an autosomal dominant inherited keratinisation disorder, although most cases are sporadic, affecting patients aged 40–50 years with no noted predominance in either sex. The condition has been described in association with endocrine abnormalities, including diabetes and hyperthyroidism, while a possible relationship with digestive and cutaneous tumours is more open to debate. Many treatment options have been discussed, including topical and systemic retinoids, 5-fluorouricil, vitamin D derivatives, psoralen, UV-A therapy, excision and dermabrasion of the lesions. At present, all of these are considered unsatisfactory due to high rates of recurrence 30.

Actinic keratoses

Actinic keratoses is a premalignant condition of thick, scaly, or crusty patches of skin. It is more common in fair-skinned people. It is associated with those who are frequently exposed to the sun, as it is usually accompanied by solar damage. Since some of these pre-cancers progress to squamous cell carcinoma, they should always be treated. When skin is exposed to the sun constantly, thick, scaly, or crusty bumps appear. The scaly or crusty part of the bump is dry and rough. The growths start out as flat scaly areas, and later grow into a tough, wart-like area.

An actinic keratosis site commonly ranges between 2–6mm in size, and can be dark or light, tan, pink, red, a combination of all of these, or have the same pigment as the surrounding skin. It may appear on any sun-exposed area, such as the face, ears, neck, scalp, chest, backs of hands, forearms or lips 31.

Warts

Warts are small rough lumps on the skin. They are caused by a virus (human papillomavirus or HPV) that causes a reaction in the skin. Warts can occur anywhere on the body, but are found most commonly on hands and feet.

Verrucas

Verrucas are warts that occur on the soles of the feet. They are the same as warts on any other part of the body. However, they may look flatter, as they tend to get trodden in (note: anal and genital warts are different).

Hyperkeratosis complications

The most common complication encountered in all types of hyperkeratosis is a foul smelling odor, produced by bacteria, when the macerated scales become infected. Without intervention, heavy bacterial colonisation may result in sepsis at any age. Epidermolytic hyperkeratosis is generalised redness, with thick, generally dark, scales that tend to form parallel rows of spines or ridges, especially near large joints. The skin is fragile and blisters easily following trauma, however, the extent of blistering and amount of scale is variable. Neonatal patients may need to be transferred to the neonatal ICU for monitoring. Widespread of denuded skin can lead to infection, sepsis and electrolyte imbalance and intravenous fluids or antibiotics will be necessary. Other complications include a variety of benign and malignant skin lesions, including melanocytic lesions 32.

Although some authors have proposed a relationship between multiple minute digitate hyperkeratoses and malignancy and/or inflammatory disorders, this contention was based on a broad definition of multiple minute digitate hyperkeratoses that included disorders that are now recognised as distinct from multiple minute digitate hyperkeratoses. However, adopting the more stringent criteria proposed by Caccetta et al 6, their findings did not find evidence for associating multiple minute digitate hyperkeratoses with malignancy or systemic disease. That stated, malignancy screening could still be considered 6.

Babies with lamellar ichthyosis are at risk of infection when the collodian membrane is shed. Later in life, eye problems may occur because the eyes cannot close completely. Pre-natal morbidity due to sepsis is a concern, therefore, an intensive care environment should be considered for affected children. Widespread areas of denuded skin may also lead to fluid and electrolyte imbalances, especially in infants 33.

In the case of X-linked ichthyosis, aside from the skin scaling, it is not typically associated with other major medical problems. Corneal opacities may be present but do not affect vision. Cryptorchidism is reported in some individuals 33. Mental retardation can also be seen in some affected individuals, and is thought to be due to deletions encompassing neighboring genes in addition to steroid sulfatase 34.

Larger deletions that include the SHOX gene can result in short stature. Female carriers generally do not experience any of these problems, but can sometimes have difficulty during childbirth, as the steroid sulfatase expressed in the placenta plays a role in normal labour. For this reason, carriers should ensure their obstetrician is aware of the condition 7.

Untreated lesions in actinic keratosis have upto 20% risk of progression to squamous cell carcinoma and should be treated immediately. Preventive measures recommended are similar to those for skin cancer 31.

With plantar hyperkeratosis, calluses are basically caused by shoes with pointed toes, short toes, or both. If untreated these can force the toes to buckle and thus produce a ‘hammer toe’ deformity at the joints 10.

After the rash has cleared up, a change in skin colour may occur (a brown or grey mark), which can sometimes last for months. This is known as post-inflammatory hyperpigmentation, and tends to be more noticeable in people with darker skin. Additionally, there is some evidence that lichen planus may increase the risk of certain cancers, such as squamous cell carcinoma, and oral, penile and vulvovaginal cancer.

Lesions affecting the vulva and vagina often do not respond well to treatment and are difficult to manage. Therefore, the condition can result in significant sores or permanent changes to vulvovaginal tissues that at times may scar. Because severe itching, pain and burning sensations are common, the condition can result in subsequent sexual dysfunction 26.

Complications of seborrheic keratosis include, skin abscesses, cellulitis, impetigo and scarring. Malignant melanoma associated with seborrheic keratosis has rarely been reported in the literature, with disagreement regarding whether it is coincidental or whether malignant transformation occurs. Because seborrheic keratoses are common and association with malignant melanoma is very rare, many experts conclude that the association is coincidental. However, because of the association of other malignancies, a biopsy of any suspect or changing seborrheic keratosis is essential 35.

Corns and callus that are not treated will become painful. They will not heal independently unless the associated pressure is removed. If it is not, then the skin will continue to thicken and become more painful. After a while, the body will start treating it as a foreign body and an ulcer (abscess) can develop. This can get infected and the infection can spread. Instances of infections of corns on the toe are more common than calluses. This can be a serious complication for those with poor circulation, peripheral neuropathy and those requiring diabetic foot care 27.

Hyperkeratosis treatment

Due to the visual similarities in some these conditions, it is vital to ensure that the correct diagnosis is confirmed prior to initiating treatment. A multidisciplinary approach is key to early detection, correct diagnosis and management of these patients. A clinician usually reaches the diagnosis of hyperkeratosis using a detailed history and embarking on a thorough skin inspection.

Laboratory investigations are often needed in order to arrive at a correct diagnosis, as many of these conditions share clinical similarities. Skin biopsy specimens from involved areas may be required for histopathological purposes. The exact mode of treatment depends on the type of hyperkeratosis.

Actinic keratosis

- An emollient may be sufficient for mild lesions

- Diclofenac sodium 3% gel is suitable for the treatment of superficial lesions in mild disease Apply thinly to affected areas for 60 to 90 days 36. Diclofenac sodium 3% gel — may cause gastrointestinal disturbances including nausea, diarrhoea and occasional bleeding and ulcera-tion. Contraindicated in hepatic, liver, respira-tory, renal and cardiac impairment.

- 5-fluorouracil cream is effective against most types of non-hypertrophic actinic keratosis. Apply thinly to the affected area once or twice daily for 3–4 weeks 36. 5-fluorouracil — local irritation (use a topical corticosteroid for severe discomfort associated with inflammatory reactions). Photosensitiv-ity. Max area of skin to be treated at one time is 500cm²

- Imiquimod (immune response modifier) is used topoi-cally for lesions of the face and scalp when cryotherapy or other topical treatments cannot be used. Apply to lesions three times a week for four weeks, assess and repeat four-week course if lesions persist — maximum two-week course 36. Imiquimod — avoid normal or broken skin and open wounds. Itching, burning sensation, ery-thema, erosion, oedema, excoriation and scab-bing, headache and influenza type symptoms. Less commonly local ulceration and alopecia 36.

- Cryosurgery with liquid nitrogen, by freezing off the actinic keratosis.

- Photodynamic therapy is a new therapy involves in-jecting a chemical into the bloodstream, which makes actinic keratosis more sensitive to any form of light.

- Laser therapy, notably CO2 and Er:YAG lasers. A Laser resurfacing technique is often used with diffuse actinic keratosis.

- Electrocautery — this involves burning off actinic keratosis with electricity.

- Different forms of surgery 31

Corns and calluses

- Paring and trimming. The thickened skin of a corn or callus can be pared down (trimmed) by a podia-trist by using a scalpel blade.

- Correcting poor footwear will reduce any rubbing or friction on your skin. In many cases, a corn or callus will go away if rubbing or pressure is pre-vented through improved footwear.

- Depending on the site of a corn or callus, a cush-ioning pad or shoe insole may be of benefit.

- Surgery is recommended for foot or toe abnormal-ity causing recurring problems 37.

Epidermolytic hyperkeratososiis

- Gene therapy is really the only true therapy for people with epidermolytic hyperkeratososiis. Until gene therapy solu-tions finally become a reality, epidermolytic hyperkeratososiis sufferers must treat their fragile skin carefully. Most have learned that taking regular, extended baths allows patients to care for their fragile skin and keep it manageable. Baths that include sea salt seem to improve the process of softening and removing the thickened skin 38.

- Oral retinoids — etretinate, acitretin, isotretinoin 38. Contraindicated in hyperlipidaemia, renal and hepatic impairment. Oral retinoid therapy frequently causes revers-ible changes in liver function and serum lipid. Up to 75% of retinoid-treated patients experi-ence dose-related hair loss, which is reversible upon discontinuation of therapy. Acitretin. Acitretin can cause major foetal abnormali-ties and is therefore contraindicated in pregnant women.

- Topical retinoids are also contraindicated in pregnancy. Local reactions include: burning, erythema, stinging, pruritus, dry/peeling skin 38.

Focal acral hyperkeratosis

- Treatment is not indicated in most patients

- Mild keratolytics occasionally help, but recurrences are common

- Topical retinoids are not effective

Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans

- Topical 5% fluorouracil and a synthetic vita-min D-3 derivative over several months have been used together with effective results.

- Local excision may be successful, especially if the number of lesions is small.

- Dermabrasion is a possible surgical modality. However, a large number of lesions, as well as lesion location, make this an impractical approach.

- Cryotherapy is an additional possibility how-ever this causes pain, swelling and blistering.

- Oral retinoids have been successful only with continuous therapy. Patients tend to relapse when therapy has ended 30.

Hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola

The disease has a benign course and may only be a cosmetic problem. Treatment with topical retinoic acid can induce an acceptable response 39.

Keratosis pilaris (follicular hyperkeratosis)

- Daily exfoliating and moisturising. These actions may make the appearance less visible.

- Suggest spending some time with the affected area in sunlight for a few minutes each day to minimise the appearance.

Lamellar ichthyosis

- Moisturizers containing urea, ammonium lactate, or other alpha-hydroxy acids may help.

- Close monitoring of fluids, electrolytes, signs of sepsis and placement in a high-humidity incubator for all newborns.

- Retinoid medications, such as tazarotene, may be used on the skin (topically). Apply once daily to the affected areas in the evening, usually for 12 weeks. Not recommended for child under 18 years of age. Topical tazarotene can cause local irritation, pruritus, burning, erythema, non-specific rash, dry or painful skin 36.

- Gene therapy to correct the genetic defect may be possible in the future 7.

Lichen planus

- No treatment is an option if symptoms are mild.

- A steroid cream or ointment can reduce inflam-mation. Steroid pastes or mouthwashes may help to ease painful mouth ulcers. A course of steroid tablets may be advised. Steroid tablets taken for longer than a few weeks are not usually advised due to possible side effects. Therefore, the rash may reappear after the tablets are stopped.

- Ciclosporin or cyclosporine and azathioprine are recommended if lichen planus is severe. These reduce inflamma-tion. Potential serious side effects mean that they are not used routinely. Oral ciclosporin — abnormal renal function, uncontrolled hypertension, infections not under control, malignancy, UVB sensitiv-ity. Contra-indicated in hepatic and renal impairment/pregnancy. Oral azathioprine — malaise, dizziness, vomiting, diarrhoea, fever, rigors, myalgia, hy-potension and interstitial nephritis. Also bone marrow suppression, liver impairment, jaundice and hair loss.

- PUVA (psoralen and UVA) is a special light therapy that may be advised by a skin specialist if you have extensive and severe lichen planus.

- Psoralen increases the skin’s sensitivity to UV light and can be administered topically or orally 1.5–2 hours before exposure to ultraviolet light 36.

- Antihistamine medicines may help to ease the itch.

- Emollients are often also given to provide moisture to your skin. These can also help to reduce the itching.

Multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis

- Topical keratolytics combined with topical emollients. Topical keratolytics – can cause pain, itching, burning, irritation, inflammation, dryness, swelling and tenderness at site of application. This will heal once treatment is complete.

- Tretinoin cream and oral vitamin A. Tretinoin cream can cause stinging, burning, dry and peeling skin, sensitivity to UVB light. Eye irritation and edema.

- Topical 5-fluorouracil cream – apply thinly to the affected area once or twice per day (max area 500cm2 for three to four weeks 36. Topical 5-fluorouracil cream can cause local irritation and photosensitivity 36.

- Surgical care – the lesions can be trimmed or clipped as needed.

- Diet – gluten-free diet plus frequent follow up.

Plantar hyperkeratosis

- Topical cream formulation containing 10% urea and 8% glycerine. The water-binding, keratolytic, exfoliative, and epidermal-thinning activities of urea and the skin softening and skin barrier repair properties of glycerine, combine to deliver significant relief 40.

- Palliative measures such as reduction of the horny accumulation and then padding of the area to distribute pressure give relief in most cases.

- Intractable conditions over a non-weight bearing area respond to excision of the condylar promi-nence 10.

Seborrheic keratosis

- A variety of techniques may be used to treat seborrheic keratosis. They include cryotherapy with carbon dioxide (dry ice) or liquid nitrogen, electro-des-iccation and curettage, curettage alone, shave biopsy or excision, or laser or dermabrasion surgery. However, some of these techniques destroy the lesion without providing a specimen for histopathologic diagnosis.

- Ammonium lactate and alpha hydroxy acids have been reported to reduce the height of seborrheic kerato-sis. Superficial lesions can be treated under expert su-pervision by applying these treatments and repeating if the full thickness is not removed on the first treatment. There is some evidence that superficial peeling will hasten the transition of closed lesions to the surface of the epidermis resulting in a quicker clearance 41. Ammonium lactate — do not apply to the face unless advised by a doctor. Do not apply on sunburned, wind-burned, dry, cracked, irritated, or broken skin. Avoid exposure to sunlight or artifi-cial UV rays. Contraindicated in pregnancy.

- Topical treatment with tazarotene applied once daily to the affected areas in the evening usually for 12 weeks.

- Not recommended for children under 18 years of age.

Warts

- No treatment may be required. Warts may regress on their own and treatment may only be required if they are painful, unsightly, persistent or cause dis-tress. Treatment usually relies on tissue destruction.

- Salicylic acid is suitable for treating warts of the hands and feet but not suitable for anogential warts. Apply carefully to wart ensuring to protect the surrounding skin with soft paraffin or appropriate dressing. Rub wart gently with file or pumice stone once weekly. Salicylic acid treatment may need to continue for up to three months. Salicylic acid is not suitable for diabetic patients at risk of naturopathic ulcers. Avoid broken skin. Not suitable for application to face, anogential re-gion, or large areas and may cause skin irritation.

- Cryotherapy causes pain, swelling and blistering and may be no more effective than topical salicylic acid.

X-linked ichthyosis

- There is no cure for X-linked ichthyosis. The main goal of treatment is to moisturise and exfoliate. This helps prevent dryness, scaling, cracking and build-up of skin.

- Oral retinoids, such as acitretin or isotretinoin, can help to reduce scaling. Oral isotretinion — dry skin, epidermal fragility, dry lips/eyes/mouth, inflammatory bowel disease, depression, hypersensitivity, hypertension, blurred vision. Contraindicated in hypervitaminosis A, hyperlipidaemia, renal and hepatic impairment and pregnancy.

- Topical isotretinoin – apply thinly once or twice daily. Topical isotretinion — contraindicated in preg-nancy. Women of childbearing years must use effective contraception. Local reactions include burning, erythema, stinging, pruritus. Eye irritation and edema, blistering or crusting of skin have been reported 36.

- Lanolin creams and products containing urea, lactic acid and other alpha hydroxyl acids may help to exfoliate and moisturise skin 36.

Hyperkeratosis prognosis

The prognosis is good for most types of hyperkeratosis, however, actinic keratosis and, very rarely, seborrheic keratosis, can develop into skin cancers. As researchers learn more about the condition and what causes it, they continue to move closer to effective treatments, and perhaps, ultimately, a cure.

References- Peckham JC, Heider K. 1999. Skin and subcutis. In: Pathology of the Mouse: Reference and Atlas (Maronpot RR, Boorman GA, Gaul BW, eds). Cache River Press, Vienna, IL, 555–612.

- Kumar V, Fausto N, Abbas A (2004) Robbins & Cotran Pathologic Basis of Disease (7th ed). Saunders, US: 1230

- The effective management of hyperkeratosis. Wounds Essentials 2012, Vol 1, page 65-73 https://www.woundsinternational.com/uploads/resources/content_10454.pdf

- Freedberg IM, Eisen AZ, Wolff K, Austen KF et al (2003) Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed). McGraw-Hill, Columbus, USA

- Goldstein N (1976). Multiple Minute Digitate Hyperkeratoses. Arch Dermatol 96(6): 692–3

- Caccetta T, Dessauvagie B, McCallum D, Kumarasinghe S (2010) Multiple minute digitate hyperkeratosis: A proposed algorithm for the digitate keratoses. J Am Acad Dermatol Nov: 1 [Epub ahead of print]

- Morelli JG (2007). Disorders of keratinization. In: Kliegman RM, Behrman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, eds. Nelson Textbook of Pediatrics (18th ed). Philadelphia, Pa: Saunders Elsevier; chapter 657

- Gelmetti C, Caputo R (2002) Pediatric Dermatology and Dermatopathology: A Concise Atlas. Informa Healthcare, London

- Nadiger, HA (1980) Role of vitamin E in the aetiology of phrynoderma (follicular hyperkeratosis) and its interrelationship with B-complex vitamins. Br J Nut 44(3): 211–14

- Skinner H, Fitzpatrick M (2008) Current Essentials: Orthopedics. McGraw–Hill Medical, USA

- Soriano LF, Piansay-Soriano ME. Naevoid hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola: an extensive form in two adolescent Filipino females. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015 Jan. 40 (1):23-6.

- Perez-Izquierdo JM, Vilata JJ, Sanchez JL, Gargallo E, Millan F, Aliaga A. Retinoic acid treatment of nipple hyperkeratosis. Arch Dermatol. 1990 May. 126(5):687-8.

- Chikhalkar SB, Misri R, Kharkar V. Nevoid hyperkeratosis of nipple: nevoid or hormonal?. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2006 Sep-Oct. 72(5):384-6.

- Aytekin S, Tarlan N, Alp S, Uzunlar AK. Naevoid hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2003 Mar. 17(2):232-3.

- Baz K, Kokturk A, Kaya TI, Ikizoglu G, Düsmez D, Koca A. A case of hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola resulting from organoid nevus. Int J Dermatol. 2003 Apr. 42(4):318-20.

- Samimi M, Maitre F, Esteve E. [Hyperkeratotic lesion of the nipple revealing cutaneous leiomyoma]. Ann Dermatol Venereol. 2008 Aug-Sep. 135(8-9):571-4.

- D’Souza M, Gharami R, Ratnakar C, Garg BR. Unilateral nevoid hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola. Int J Dermatol. 1996 Aug. 35(8):602-3.

- Lee HW, Suh HS, Choi JC, et al. Hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola as a sign of malignant acanthosis nigricans. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005 Nov. 30(6):721-2.

- Fitzgerald DA, Lewis-Jones MS. Darier’s disease presenting as isolated hyperkeratosis of the breasts. Br J Dermatol. 1997 Feb. 136(2):290.

- Ahn SK, Chung J, Soo Lee W, Kim SC, Lee SH. Hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola simultaneously developing with cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1995 Jan. 32(1):124-5.

- Kavak A, Parlak AH, Aydogan I, Alper M. Hyperkeratosis of the nipple and areola in a patient with chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. J Dermatol. 2006 Jul. 33(7):510-1.

- Mold DE, Jegasothy BV. Estrogen-induced hyperkeratosis of the nipple. Cutis. 1980 Jul. 26(1):95-6.

- Lambiris AG, McCormick F. Unilateral hyperkeratosis of nipple and areola associated with androgen insensitivity and oestrogen replacement therapy. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2001 Jul. 15(4):376-7.

- Carr ES, Brown SC, Fiala KH. Painful nipple hyperkeratosis secondary to vemurafenib. Dermatol Ther. 2017 Feb 17.

- Parimalam K, Chandrakala C, Ananthi M, Karpagam B. Nipple Hyperkeratosis Due to Malassezia Furfur Showing Excellent Response to Itraconazole. Indian J Dermatol. 2015 May-Jun. 60 (3):324.

- Lehman JS, Tollefson MM, Gibson LE (2009) Lichen planus. Int J Dermatol 48(7): 682–94

- Freeman DB (2002) Corns and calluses resulting from mechanical hyperkeratosis. Am Fam Physician 1: 65(11): 2277–80

- Rapini RP, Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL (2007) Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. Mosby, St Louis

- Miljkovic J (2004) An unusual generalized form of hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease). Wien Klin Wochenschr 116 Suppl 2: 78–80

- Metze D, Lübke D, Luger T (2000).[Hyperkeratosis lenticularis perstans (Flegel’s disease) — a complex disorder of epidermal differentiation with good response to a synthetic vitamin D3 derivate]. Hautarzt 51(1): 31–5

- Quaedvlieg PJ, Tirsi E, Thissen MR, Krekels GA (2006) Actinic keratosis: how to differentiate the good from the bad ones? Eur J Dermatol 16(4): 335–39

- Hutcheson AC, Nietert PJ, Maize JC (2004) Incidental epidermolytic hyperkeratosis and focal acantholytic dyskeratosis in common acquired melanocytic nevi and atypical melanocytic lesions. J Am Acad Dermatol 50(3): 388–90

- Di Giovanna JJ, Robinson-Bostom L (2003) Ichthyosis: etiology, diagnosis, and management. Am J Clin Dermatol 4(2): 81–95

- Van Esch H, Hollanders K, Badisco L, Melotte C, et al (2005) Deletion of VCX-A due to NAHR plays a major role in the occurrence of mental retardation in patients with X-linked ichthyosis. Hum Mol Genet 14, 13

- Zabel RJ, Vinson RP, McCollough ML (2000) Malignant melanoma arising in a seborrheic keratosis. J Am Acad Dermatol 42(5): 831–33

- BMJ/RPS (2012) British National Formulary 63. March, BMJ Group Macmillan, London

- Hogan DJ, Basile AL. Corns. eMedicine. January 2008

- Brecher AR, Orlow SJ (2003) Oral retinoid therapy for dermatologic conditions in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol 49(2): 171–82

- Perez-Izquierdo JM, Vilata JJ, Sanchez JL, et al (1990) Retinoic acid treatment of nipple hyperkeratosis. Arch Dermatol 126: 687–88

- Loden M (2003) Role of topical emollients and moisturizers in the treatment of dry skin barrier disorders. Am J Clin Dermatol 4(11): 771–88

- Kempiak S, Uebelhoer N (2008) Superficial chemical peels and microdermabrasion for acne vulgaris. Seminars in Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 27(3): 212–20