Hypokinesia

Hypokinesia refers to decreased bodily movement. Hypokinesiat is characterized by slow movement (bradykinesia) or no movement (akinesia) 1. In Parkinson’s disease, hypokinesia co-occurs with tremor at rest and with rigidity. Hypokinesia is caused by basal ganglia damage and in Parkinson’s disease, with loss of the dopaminergic cells in the substantia nigra pars compacta. The general hypothesis underlying hypokinesia is that there is an overactive indirect basal ganglia pathway, resulting in nearly constant thalamic inhibition, and the inability to select the desired motor plan 1. Clinically, hypokinesia appears as frequent muscle co-contraction where there is difficulty turning off the muscles that are not needed and turning on the muscles that are needed to execute a particular movement 1. These muscle problems lead to a flexed-forward posture with instability and a slow, shuffling gait. People with hypokinesia have difficulty getting started with movement and can freeze during movement 1. The major upper extremity movement complaint is tremor and small, sometimes illegible, handwriting (termed micrographia). Postural instability, gait deficits, tremor, and micrographia will worsen with disease progression and as pharmacologic management of the disease becomes less effective.

Hypokinesia describes a variety of more specific disorders: 2:

- Bradykinesia: Slowness of initiation of voluntary movement with a progressive reduction in speed and range of repetitive actions, such as voluntary finger-tapping 3. Bradykinesia occurs in Parkinson’s disease and other disorders of the basal ganglia. It is one of the four key symptoms of parkinsonism, which are bradykinesia, tremor, rigidity, and postural instability 4.

- Akinesia: Inability to initiate voluntary movement.

- Dyskinesia: Dyskinesia is characterized by a diminished ability for voluntary movements, as well as the presence of involuntary movements. The hands and upper body are the areas most likely to be affected by tremors and tics. In some cases, Parkinson’s patients experience dyskinesia as a negative side effect of dopamine medications 5.

- Freezing: This is characterized by an inability to move muscles in any desired direction.

- Rigidity: The increase in muscle tension when moved by an outside force. For example, resistance to externally imposed (“passive”) joint movements, such as when a doctor flexes a patient’s arm at the elbow joint 6. It does not depend on imposed speed and can be elicited at very low speeds of passive movement in both directions. Cogwheel rigidity and leadpipe rigidity are two types identified with Parkinson’s disease:

- Leadpipe rigidity is sustained resistance to passive movement throughout the whole range of motion, with no fluctuations.

- Cogwheel rigidity is jerky resistance to passive movement as muscles tense and relax.

- Spasticity, a special form of rigidity, is present only at the start of passive movement. It is rate-dependent and only elicited upon a high-speed movement. These various forms of rigidity can be seen in different forms of movement disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease.

- Postural instability: Loss of ability to maintain an upright posture when standing and walking. In Parkinsons disease it is correlated with greater disability and more depression, as well as with frequency of falls and fear of falls (which, itself, can be significantly disabling) 7.

- Dystonia: A movement disorder characterised by sustained muscle contractions, frequently causing twisted and repetitive movements, or abnormal postures 8.

- Dysarthria: A condition which affects the muscles necessary for speech, it causes difficulty in speech production despite a continued cognitive understanding of language. Often caused by Parkinson’s disease, patients experience weakness, paralysis, or lack of coordination in the motor-speech system, causing respiration, phonation, prosody, and articulation to be affected. Problems including tone, speed of communication, breath control, volume, and timing are displayed. Hypokinetic dysarthria particularly affects the volume of speech, prompting treatment with a speech language pathologist 9.

Hypokinesia common causes:

- Parkinson’s disease

- Parkinsonism or parkinsonian-like conditions

- Dementia

- Encephalitis

- Functional disorders

- Primary affective disorder

Global hypokinesia of the left ventricle

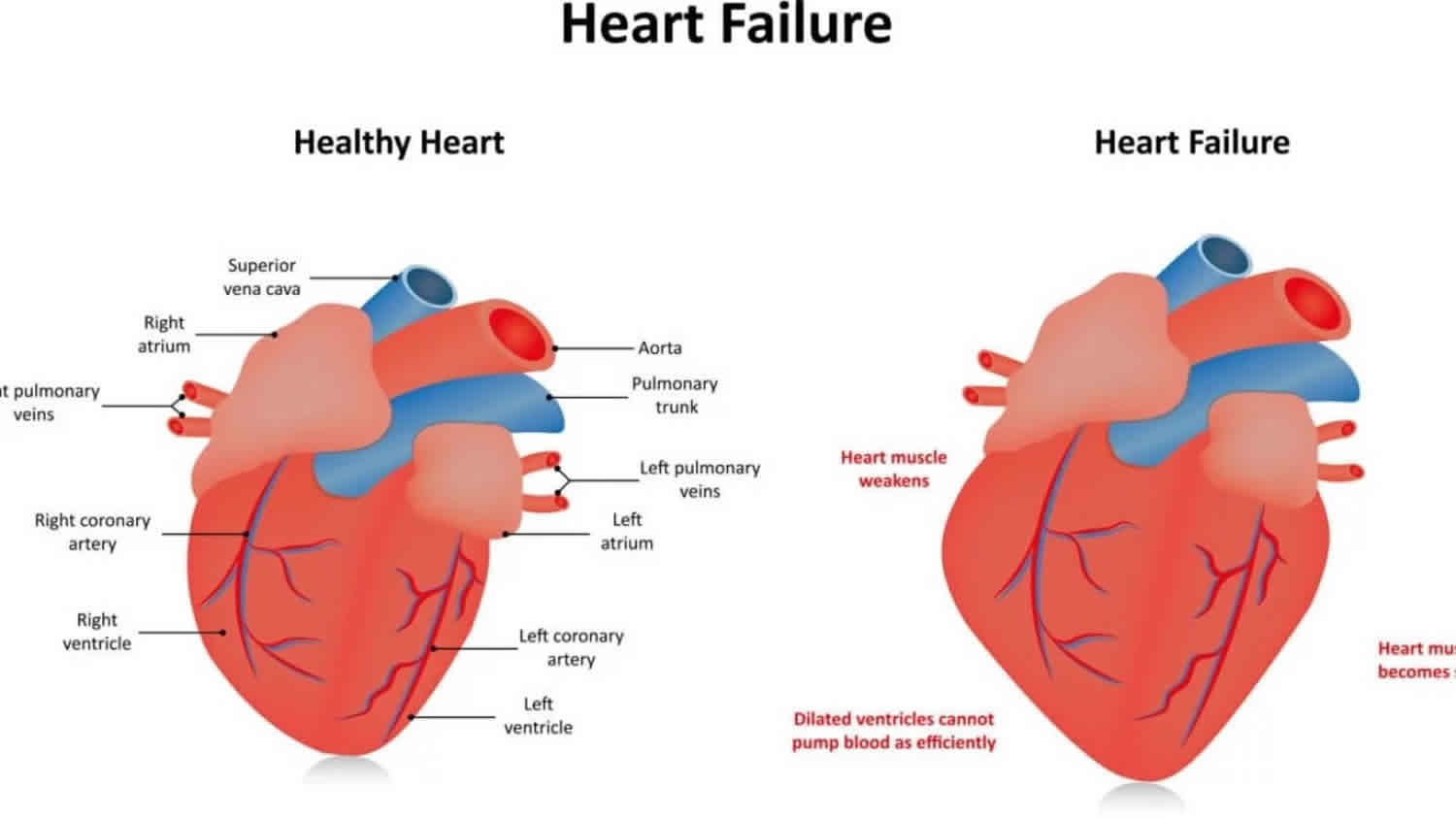

Global hypokinesis of the left ventricle is defined as a left ventricular ejection fraction of <45% 10. Global hypokinesis of the left ventricle treatment involves treating the underlying cause of the heart muscle weakness or heart failure. Heart failure is a condition in which the heart can’t pump enough blood to meet the body’s needs. Heart failure does not mean that your heart has stopped or is about to stop working. It means that your heart is not able to pump blood the way it should. It can affect one or both sides of the heart. Heart failure is a major public health problem, affecting 26 million people worldwide 11.

The weakening of the heart’s pumping ability causes:

- Blood and fluid to back up into the lungs

- The buildup of fluid in the feet, ankles and legs – called edema

- Tiredness and shortness of breath

Common causes of heart failure are coronary artery disease, high blood pressure and diabetes. It is more common in people who are 65 years old or older, African Americans, people who are overweight, and people who have had a heart attack. Men have a higher rate of heart failure than women.

To diagnose heart failure, your doctor will take a careful medical history, review your symptoms and perform a physical examination. Your doctor will also check for the presence of risk factors, such as high blood pressure, coronary artery disease or diabetes.

Using a stethoscope, your doctor can listen to your lungs for signs of congestion. The stethoscope also picks up abnormal heart sounds that may suggest heart failure. The doctor may examine the veins in your neck and check for fluid buildup in your abdomen and legs.

Classifying heart failure

Results of clinical and lab tests help doctors determine the cause of your signs and symptoms and develop a program to treat your heart. To determine the most appropriate treatment for your condition, doctors may classify heart failure using two systems:

- New York Heart Association classification. This symptom-based scale classifies heart failure in four categories. In Class I heart failure, you don’t have any symptoms. In Class II heart failure, you can perform everyday activities without difficulty but become winded or fatigued when you exert yourself. With Class III, you’ll have trouble completing everyday activities, and Class IV is the most severe, and you’re short of breath even at rest.

- American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association guidelines. This stage-based classification system uses letters A to D. The system includes a category for people who are at risk of developing heart failure.

For example, a person who has several risk factors for heart failure but no signs or symptoms of heart failure is Stage A. A person who has heart disease but no signs or symptoms of heart failure is Stage B. Someone who has heart disease and is experiencing or has experienced signs or symptoms of heart failure is Stage C. A person with advanced heart failure requiring specialized treatments is Stage D.

Doctors use this classification system to identify your risk factors and begin early, more aggressive treatment to help prevent or delay heart failure.

These scoring systems are not independent of each other. Your doctor often will use them together to help decide your most appropriate treatment options. Ask your doctor about your score if you’re interested in determining the severity of your heart failure. Your doctor can help you interpret your score and plan your treatment based on your condition.

Your doctor will diagnose heart failure by doing a physical exam and heart tests. Treatment includes treating the underlying cause of your heart failure, medicines, and heart transplantation if other treatments fail.

Global hypokinesis of the left ventricle treatment

Heart failure is a chronic disease needing lifelong management. However, with treatment, signs and symptoms of heart failure can improve, and the heart sometimes becomes stronger. Treatment may help you live longer and reduce your chance of dying suddenly.

Doctors sometimes can correct heart failure by treating the underlying cause. For example, repairing a heart valve or controlling a fast heart rhythm may reverse heart failure. But for most people, the treatment of heart failure involves a balance of the right medications and, in some cases, use of devices that help the heart beat and contract properly.

Medications

Doctors usually treat heart failure with a combination of medications. Depending on your symptoms, you might take one or more medications, including:

- Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors. These drugs help people with systolic heart failure live longer and feel better. ACE inhibitors are a type of vasodilator, a drug that widens blood vessels to lower blood pressure, improve blood flow and decrease the workload on the heart. Examples include enalapril (Vasotec), lisinopril (Zestril) and captopril (Capoten).

- Angiotensin II receptor blockers. These drugs, which include losartan (Cozaar) and valsartan (Diovan), have many of the same benefits as ACE inhibitors. They may be an alternative for people who can’t tolerate ACE inhibitors.

- Beta blockers. This class of drugs not only slows your heart rate and reduces blood pressure but also limits or reverses some of the damage to your heart if you have systolic heart failure. Examples include carvedilol (Coreg), metoprolol (Lopressor) and bisoprolol (Zebeta). These medicines reduce the risk of some abnormal heart rhythms and lessen your chance of dying unexpectedly. Beta blockers may reduce signs and symptoms of heart failure, improve heart function, and help you live longer.

- Diuretics. Often called water pills, diuretics make you urinate more frequently and keep fluid from collecting in your body. Diuretics, such as furosemide (Lasix), also decrease fluid in your lungs so you can breathe more easily. Because diuretics make your body lose potassium and magnesium, your doctor may also prescribe supplements of these minerals. If you’re taking a diuretic, your doctor will likely monitor levels of potassium and magnesium in your blood through regular blood tests.

- Aldosterone antagonists. These drugs include spironolactone (Aldactone) and eplerenone (Inspra). These are potassium-sparing diuretics, which also have additional properties that may help people with severe systolic heart failure live longer. Unlike some other diuretics, spironolactone and eplerenone can raise the level of potassium in your blood to dangerous levels, so talk to your doctor if increased potassium is a concern, and learn if you need to modify your intake of food that’s high in potassium.

- Inotropes. These are intravenous medications used in people with severe heart failure in the hospital to improve heart pumping function and maintain blood pressure.

- Digoxin (Lanoxin). This drug, also referred to as digitalis, increases the strength of your heart muscle contractions. It also tends to slow the heartbeat. Digoxin reduces heart failure symptoms in systolic heart failure. It may be more likely to be given to someone with a heart rhythm problem, such as atrial fibrillation.

You may need to take two or more medications to treat heart failure. Your doctor may prescribe other heart medications as well — such as nitrates for chest pain, a statin to lower cholesterol or blood-thinning medications to help prevent blood clots — along with heart failure medications. Your doctor may need to adjust your doses frequently, especially when you’ve just started a new medication or when your condition is worsening.

You may be hospitalized if you have a flare-up of heart failure symptoms. While in the hospital, you may receive additional medications to help your heart pump better and relieve your symptoms. You may also receive supplemental oxygen through a mask or small tubes placed in your nose. If you have severe heart failure, you may need to use supplemental oxygen long term.

Surgery and medical devices

In some cases, doctors recommend surgery to treat the underlying problem that led to heart failure. Some treatments being studied and used in certain people include:

- Coronary bypass surgery. If severely blocked arteries are contributing to your heart failure, your doctor may recommend coronary artery bypass surgery. In this procedure, blood vessels from your leg, arm or chest bypass a blocked artery in your heart to allow blood to flow through your heart more freely.

- Heart valve repair or replacement. If a faulty heart valve causes your heart failure, your doctor may recommend repairing or replacing the valve. The surgeon can modify the original valve to eliminate backward blood flow. Surgeons can also repair the valve by reconnecting valve leaflets or by removing excess valve tissue so that the leaflets can close tightly. Sometimes repairing the valve includes tightening or replacing the ring around the valve (annuloplasty). Valve replacement is done when valve repair isn’t possible. In valve replacement surgery, the damaged valve is replaced by an artificial (prosthetic) valve. Certain types of heart valve repair or replacement can now be done without open heart surgery, using either minimally invasive surgery or cardiac catheterization techniques.

- Implantable cardioverter-defibrillators (ICDs). An implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) is a device similar to a pacemaker. It’s implanted under the skin in your chest with wires leading through your veins and into your heart. The ICD monitors the heart rhythm. If the heart starts beating at a dangerous rhythm, or if your heart stops, the ICD tries to pace your heart or shock it back into normal rhythm. An ICD can also function as a pacemaker and speed your heart up if it is going too slow.

- Cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT), or biventricular pacing. A biventricular pacemaker sends timed electrical impulses to both of the heart’s lower chambers (the left and right ventricles) so that they pump in a more efficient, coordinated manner. Many people with heart failure have problems with their heart’s electrical system that cause their already-weak heart muscle to beat in an uncoordinated fashion. This inefficient muscle contraction may cause heart failure to worsen. Often a biventricular pacemaker is combined with an ICD for people with heart failure.

- Ventricular assist devices (VADs). A VAD, also known as a mechanical circulatory support device, is an implantable mechanical pump that helps pump blood from the lower chambers of your heart (the ventricles) to the rest of your body. A VAD is implanted into the abdomen or chest and attached to a weakened heart to help it pump blood to the rest of your body. Doctors first used heart pumps to help keep heart transplant candidates alive while they waited for a donor heart. VADs may also be used as an alternative to transplantation. Implanted heart pumps can enhance the quality of life of some people with severe heart failure who aren’t eligible for or able to undergo heart transplantation or are waiting for a new heart.

- Heart transplant. Some people have such severe heart failure that surgery or medications don’t help. They may need to have their diseased heart replaced with a healthy donor heart. Heart transplants can improve the survival and quality of life of some people with severe heart failure. However, candidates for transplantation often have to wait a long time before a suitable donor heart is found. Some transplant candidates improve during this waiting period through drug treatment or device therapy and can be removed from the transplant waiting list. A heart transplant isn’t the right treatment for everyone. A team of doctors at a transplant center will evaluate you to determine whether the procedure may be safe and beneficial for you.

Lifestyle and home remedies

Making lifestyle changes can often help relieve signs and symptoms of heart failure and prevent the disease from worsening. These changes may be among the most important and beneficial you can make. Lifestyle changes your doctor may recommend include:

- Stop smoking. Smoking damages your blood vessels, raises blood pressure, reduces the amount of oxygen in your blood and makes your heart beat faster. If you smoke, ask your doctor to recommend a program to help you quit. You can’t be considered for a heart transplant if you continue to smoke. Avoid secondhand smoke, too.

- Discuss weight monitoring with your doctor. Discuss with your doctor how often you should weigh yourself. Ask your doctor how much weight gain you should notify him or her about. Weight gain may mean that you’re retaining fluids and need a change in your treatment plan.

- Check your legs, ankles and feet for swelling daily. Check for any changes in swelling in your legs, ankles or feet daily. Check with your doctor if the swelling worsens.

- Eat a healthy diet. Aim to eat a diet that includes fruits and vegetables, whole grains, fat-free or low-fat dairy products, and lean proteins.

- Restrict sodium in your diet. Too much sodium contributes to water retention, which makes your heart work harder and causes shortness of breath and swollen legs, ankles and feet. Check with your doctor for the sodium restriction recommended for you. Keep in mind that salt is already added to prepared foods, and be careful when using salt substitutes.

- Maintain a healthy weight. If you’re overweight, your dietitian will help you work toward your ideal weight. Even losing a small amount of weight can help.

- Consider getting vaccinations. If you have heart failure, you may want to get influenza and pneumonia vaccinations. Ask your doctor about these vaccinations.

- Limit saturated or ‘trans’ fats in your diet. In addition to avoiding high-sodium foods, limit the amount of saturated fat and trans fat — also called trans-fatty acids — in your diet. These potentially harmful dietary fats increase your risk of heart disease.

- Limit alcohol and fluids. Your doctor may recommend that you don’t drink alcohol if you have heart failure, since it can interact with your medication, weaken your heart muscle and increase your risk of abnormal heart rhythms.If you have severe heart failure, your doctor may also suggest you limit the amount of fluids you drink.

- Be active. Moderate aerobic activity helps keep the rest of your body healthy and conditioned, reducing the demands on your heart muscle. Before you start exercising though, talk to your doctor about an exercise program that’s right for you. Your doctor may suggest a walking program. Check with your local hospital to see if it offers a cardiac rehabilitation program; if it does, talk to your doctor about enrolling in the program.

- Reduce stress. When you’re anxious or upset, your heart beats faster, you breathe more heavily and your blood pressure often goes up. This can make heart failure worse, since your heart is already having trouble meeting the body’s demands. Find ways to reduce stress in your life. To give your heart a rest, try napping or putting your feet up when possible. Spend time with friends and family to be social and help keep stress at bay.

- Sleep easy. If you’re having shortness of breath, especially at night, sleep with your head propped up using a pillow or a wedge. If you snore or have had other sleep problems, make sure you get tested for sleep apnea.

Palliative care and end-of-life care

Your doctor may recommend including palliative care in your treatment plan. Palliative care is specialized medical care that focuses on easing your symptoms and improving your quality of life. Anyone who has a serious or life-threatening illness can benefit from palliative care, either to treat symptoms of the disease, such as pain or shortness of breath, or to ease the side effects of treatment, such as fatigue or nausea.

It’s possible that your heart failure may worsen to the point where medications are no longer working and a heart transplant or device isn’t an option. If this occurs, you may need to enter hospice care. Hospice care provides a special course of treatment to terminally ill people.

Hospice care allows family and friends — with the aid of nurses, social workers and trained volunteers — to care for and comfort a loved one at home or in hospice residences. Hospice care provides emotional, psychological, social and spiritual support for people who are ill and those closest to them.

Although most people under hospice care remain in their own homes, the program is available anywhere — including nursing homes and assisted living centers. For people who stay in a hospital, specialists in end-of-life care can provide comfort, compassionate care and dignity.

Although it can be difficult, discuss end-of-life issues with your family and medical team. Part of this discussion will likely involve advance directives — a general term for oral and written instructions you give concerning your medical care should you become unable to speak for yourself.

If you have an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD), one important consideration to discuss with your family and doctors is turning off the defibrillator so that it can’t deliver shocks to make your heart continue beating.

References- Geriatric Physical Therapy (Third Edition), 2012. Impaired motor control. ISBN: 978-0-323-02948-3 https://doi.org/10.1016/C2009-0-60243-9

- Kahan, Scott, Smith, Ellen G. In A Page: Signs and Symptoms. Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing, 2004:68 ISBN 140510368X

- Ling, Helen; Massey, Luke A.; Lees, Andrew J.; Brown, Peter; Day, Brian L. (April 2012). “Hypokinesia without decrement distinguishes progressive supranuclear palsy from Parkinson’s disease”. Brain: A Journal of Neurology. 135 (Pt 4): 1141–1153. doi:10.1093/brain/aws038. ISSN 1460-2156

- Parkinson Disease Clinical Presentation. https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1831191-clinical

- Robottom, Bradley J. (1 May 2011). “Movement Disorders Emergencies Part 1”. Archives of Neurology. 68 (5): 567. doi:10.1001/archneurol.2011.84

- O’Sullivan SB, Schmitz TJ (2007). “Parkinson’s Disease”. Physical Rehabilitation. 5. Philadelphia: F.A Davis Company. pp. 856–857. ISBN 978-0-80-362579-2

- Kim, Samuel D.; Allen, Natalie E.; Canning, Colleen G.; Fung, Victor S. C. (February 2013). “Postural instability in patients with Parkinson’s disease. Epidemiology, pathophysiology and management”. CNS Drugs. 27 (2): 97–112. doi:10.1007/s40263-012-0012-3

- Skogseid, I. M. (2014). “Dystonia–new advances in classification, genetics, pathophysiology and treatment”. Acta Neurologica Scandinavica. Supplementum. 129 (198): 13–19. doi:10.1111/ane.12231

- Yorkston, Kathryn M.; Mark Hakel; David R. Beukelman; Susan Fager (June 2007). “Evidence for effectiveness of treatment of loudness, rate, or prosody in dysarthria: A systematic review”. Journal of Medical Speech-Language Pathology. 15 (2): xi–xxxvi.

- Actual incidence of global left ventricular hypokinesia in adult septic shock. Crit Care Med. 2008 Jun;36(6):1701-6. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174db05

- Savarese G, Lund LH. Global public health burden of heart failure. Card Fail Rev. 2017;3:7–11.