What is iritis

Iritis is inflammation of the iris, the colored ring around your eye’s pupil (iris), but other parts of the eye can also be involved and this can be associated with local disease from the eye or from uveitis that is associated with systemic disease. The iris is a part of the middle layer of the eye (uvea), so iritis is a type of uveitis, also known as anterior uveitis. Uveitis is a term to describe a group of conditions that cause inflammation of the uvea or the middle layer of the wall of your eye.

The uvea is the middle layer of tissue in the wall of the eye. It consists of the iris, the ciliary body and the choroid. The choroid is sandwiched between the retina and the sclera. The retina is located at the inside wall of the eye and the sclera is the outer white part of the eye wall. The uvea provides blood flow to the deep layers of the retina.

The iris is a thin diaphragm composed mostly of connective tissue and smooth muscle fibers. From the outside, the iris is the colored part of the eye. The iris extends forward from the periphery of the ciliary body and lies between the cornea and lens. The iris divides the space (anterior cavity) separating these parts into an anterior chamber (between the cornea and the iris) and a posterior chamber containing the lens (between the iris and the vitreous body). The iris controls the size of the pupil, through which light passes as it enters the eye. The contractile cells of the iris are organized into two groups, a circular set and a radial set. The circular set (pupillary constrictor) is smooth muscle and acts as a sphincter. When the muscle cells contract, the pupil gets smaller, and less light enters. Bright light stimulates the circular muscles to contract, which decreases the amount of light entering the eye. The radial set (pupillary dilator) is composed of specialized contractile epithelial cells (myoepithelial cells). When these cells contract, the pupil’s diameter increases and more light enters. Dim light stimulates the radial cells to contract, which increases the amount of light entering the eye.

Iritis, the most common type of uveitis, affects the front of your eye. The cause is often unknown. It can result from an underlying systemic condition or genetic factor.

- The incidence of iritis is estimated at 12 per 100,000 in the United States.

- Iritis accounts for 90% of uveitis 1.

Iritis can affect people of all ages. The cause may be unknown, or it may be associated with certain systemic inflammatory disorders or autoimmune disorders.

Eye iritis can be acute or chronic. Acute iritis presents itself suddenly, typically as a painful red eye with light sensitivity.

Chronic iritis can last months or years, and may not respond to treatment as well as acute version. People with chronic iritis are often at higher risk for developing visual impairments.

The following are five signs of iritis that all people should be aware of. If you’ve been experiencing one or more of these symptoms, you should immediately seek medical advice from a uveitis specialist.

1. An Achy, Bloodshot Eye

One of the first and most common signs of iritis is an eye that is achy and bloodshot. While many people attribute this discomfort to normal eye irritation, the pain is usually persistent and will often be followed by the development of additional symptoms. This discomfort is the result of inflammation of the iris. It can also be felt as a dull or throbbing ache in the eye or around it.

2. Photophobia Or Sensitivity To Light

Once the iris becomes inflamed, many people develop photophobia or an inability to tolerate bright light. Immediately upon entering into a brightly lit area or stepping out into the natural sunlight, the affected eye will squeeze shut, in order to block out the brightness. The affected eye will often start to water, and you may not notice as your pupil struggles to adapt to exposed light. In a normal, healthy eye, the pupil will usually grow smaller when light exposure is increased. In people with iritis, however, the pupil does not change in size in accordance with the increase in light. This change in pupil response is the result of inflammation and the underlying cause of photophobia.

3. Blurred Vision

Many people start using eye drops on a regular basis in order to alleviate their growing discomfort and in the belief that they’re suffering from minor eye irritation. It is important to note that frequent and excessive use of eye drops can eventually lead to blurred vision. Blurry vision in people who suffer from iritis can also be the result of the inflammation of the iris.

4. Eye Floaters

Eye floaters are dark shadows and shapes that move across the surface of the eye and across the field of vision. They are most noticeable when looking at a background that is brightly lit, such as the afternoon sky. Floaters are debris from the inflammatory blood cells and can be seen as wispy dots or streaks. Eye floaters can be merely bothersome or they may have a significant impact on overall vision. Floaters are most common among people with acute iritis who have been dealing with photophobia and other iritis symptoms for some time.

5. Odd-Shaped Pupil

A small or oddly-shaped pupil is one of the top signs of iritis. The pupil can become misshapen as the result of inflammation that makes the iris become sticky and adhere to the lens. The lens sits close behind the iris. A misshapen pupil is referred to as Synechia and much like eye floaters, it is a sign of acute iritis and indicates that the problem is worsening and should be addressed right away.

If untreated, iritis could lead to glaucoma or blindness. If you have symptoms of iritis, see your doctor as soon as possible.

Figure 1. Structure of the human eye

Traumatic iritis

Traumatic iritis is inflammation of the iris due to trauma.

Traumatic iritis is usually caused by blunt eye injury 2, but can result form any other type of injury, like firecrackers, pellet gun projectile, electric shock from taser, fishing hook weight, motor vehicle accidents, batteries, water balloon sling-shots, as well as many others 3, 4.

Wearing eye protection when risk of injury to eye is increased (e.g. pellet guns, fishing, metal or woodworking) may prevent initial trauma.

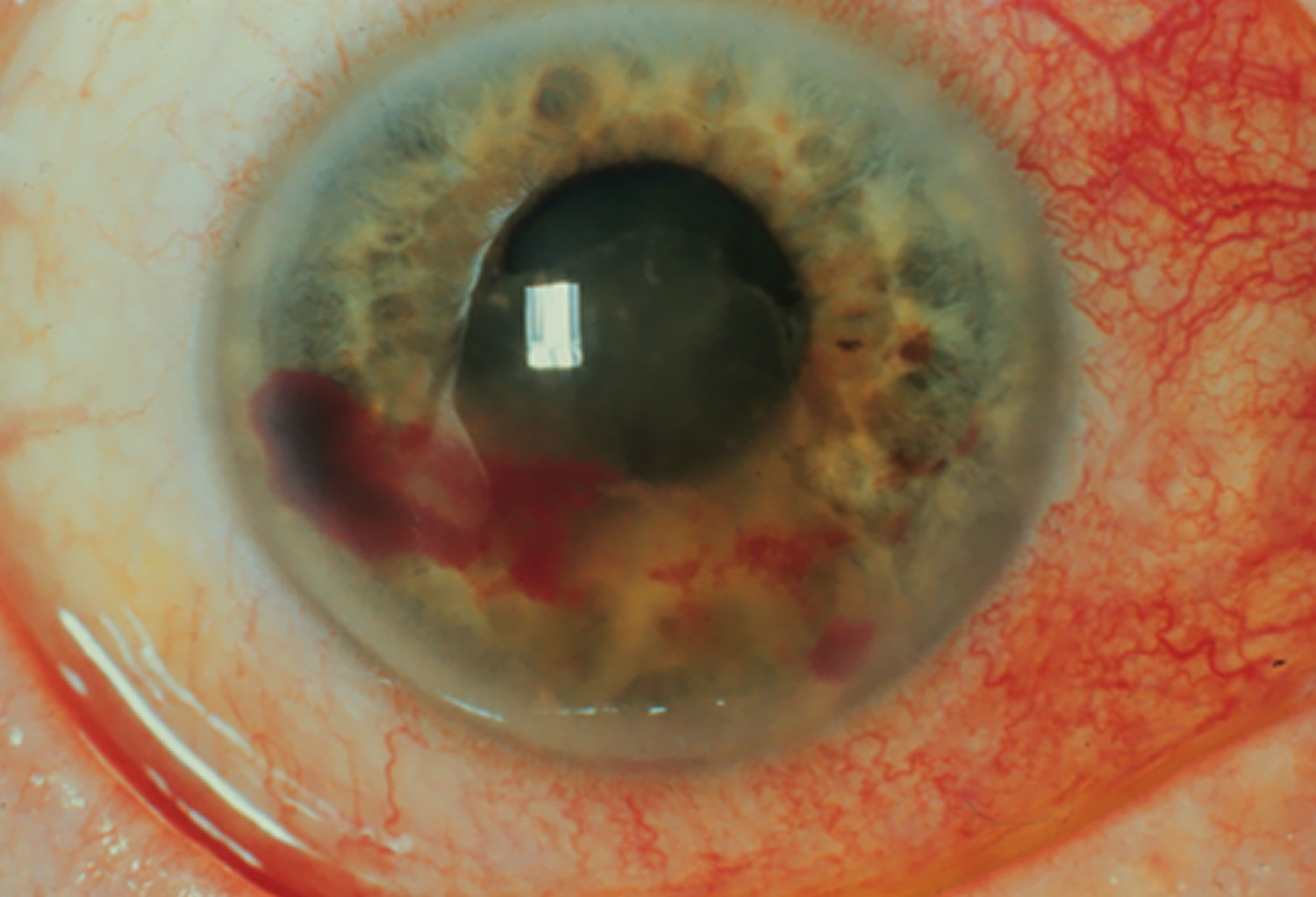

Figure 3. Traumatic iritis

Trauma is one of the most common causes of anterior uveitis 5:

- Traumatic iritis accounts for 20% of iritis 1.

- Younger patients are affected more than older patients.

- Males tend to be affected more than females.

Trauma to the eye causes injury and death to cells that subsequently form necrotic products 6. These necrotic products stimulate an inflammatory reaction. Increased permeability of blood vessels in the eye allow inflammatory cells (white blood cells), inflammatory mediators (proteins, etc.), and other blood contents to enter the eye tissue and eye media 6.

Traumatic iritis signs

- Traumatic iritis typically presents with unilateral ocular involvement.

- It may present with white blood cells and/or proteinaceous fluid in the anterior chamber; known as “cell and flare” or “anterior chamber reaction” 6.

- Visualization of cell and flare can be achieved with an intense, narrow slit beam of light at an oblique angle directed into the anterior chamber. These inflammatory products may deposit and be visualized on the endothelium of the cornea as keratic precipitates 7.

- A vossius ring of iris pigment on the anterior lens capsule may be present from impression of the posterior iris on the lens produced by the concussive force driving the iris posterior onto the lens 8.

- Precipitates may also collect in dependent areas to form a hypopyon 9.

- Decreased visual acuity, perilimbal conjunctival injection (redness of the eye/ciliary flush), and change in intraocular pressure (IOP) are also associated with traumatic iritis 6.

- Intraocular pressure (IOP) may be increased due to inflammatory process or it may be decreased due to damage of the ciliary body’s ability to produce aqueous humor 10.

- Miosis may result as nociceptive reflex of photophobia or mydriasis due to iris sphincter tears 10.

- Inflammation of the iris may cause synechial formations between the inflamed, miotic iris and anterior lens 6. *Circumferential synechia may block the flow of aqueous fluid from exiting the posterior chamber causing increased pressure and may distend the iris forward like an umbrella to form what is called an iris bombé 9.

- Intractable secondary glaucoma may also result following traumatic iritis 9.

Traumatic iritis symptoms

- Photophobia (pain when light enters eye; pain with miosis)

- Decreased visual acuity

- Floaters

- Tearing

- Ocular pain (typically dull achy or throbbing) not relieved by topical anesthetic; typically occur within the first 3 days of the traumatic event 6.

Traumatic iritis treatment

Medical therapy

- Topical cycloplegics (e.g. cyclopentalate 2% three times daily, scopolamine 0.25% twice daily) will dilate the pupil and prevent synechiae to the lens. They also stabilize the blood-aqueous barrier to prevent further protein leakage (flare) 5. Topical cycloplegics will also prevent ciliary body and pupillary spasm that causes pain and discomfort 6.

- Topical steroids (e.g. prednisolone acetate 0.125-1% four times daily) are used to decrease inflammation. They are avoided if there is a corneal epithelial defect.

- Topical beta-blockers (e.g. timolol maleate 0.5% twice daily) may be beneficial if secondary glaucoma is present and there are no other contraindications to beta-blocker usage 5.

Follow up

Add text here It is recommended to follow up in 5-7 days of the initial traumatic event. If iritis is resolved, cycloplegia may be discontinued and steroid may be tapered then discontinued. The risk of rebound iritis increases if steroid is not tapered 6.

Follow up should also occur at 1 month 11. Gonioscopy should be performed to rule out angle recession at this visit 11. Indirect ophthalmoscopy should be performed using scleral depression to rule out retinal breaks and retinal detachments 11.

Traumatic iritis prognosis

Most patients respond well to current standard treatments. Some patients will have recurrence or lingering signs and symptoms. Complications can include decreased visual acuity and/or blindness, glaucoma, cataracts (duration of inflammation is directly related to risk), irregular pupil (due to synechia formation, tearing, and sloughing of inflamed iris), band keratopathy, and cystoid macular edema 6.

Uveitis vs Iritis

Uveitis is a term to describe a group of conditions that cause inflammation of the uvea or the middle layer of the wall of your eye. Iritis is a form of uveitis – anterior uveitis – that affects the front of your eye and is the most common type of uveitis accounting for 75 percent of cases. Anterior uveitis occurs in the front of the eye – when the iris and the ciliary body become inflamed. Anterior uveitis predominantly occurrs in young and middle-aged people. Many cases occur in healthy people and may only affect one eye but some are associated with rheumatologic, skin, gastrointestinal, lung and infectious diseases.

Iritis complications

If not treated properly, iritis could lead to:

- Cataracts. Development of a clouding of the lens of your eye (cataract) is a possible complication, especially if you’ve had a long period of inflammation.

- An irregular pupil. Scar tissue can cause the iris to stick to the underlying lens or the cornea, making the pupil irregular in shape and the iris sluggish in its reaction to light.

- Glaucoma. Recurrent iritis can result in glaucoma, a serious eye condition characterized by increased pressure inside the eye and possible vision loss.

- Calcium deposits on the cornea (band keratopathy). This causes degeneration of your cornea and could decrease your vision.

- Swelling within the retina (cystoid macular edema). Swelling and fluid-filled cysts that develop in the retina at the back of the eye (macular retina) can blur or decrease your central vision.

Iritis causes

What causes iritis

Often, the cause of iritis can’t be determined. In some cases, iritis can be linked to eye trauma, genetic factors or certain diseases.

Causes of iritis include:

- Injury to the eye. Blunt force trauma, a penetrating injury, or a burn from a chemical or fire can cause acute iritis.

- Infections. Shingles (herpes zoster) on your face can cause iritis. Other infectious diseases, such as toxoplasmosis, Lyme disease, histoplasmosis, tuberculosis and syphilis, can be linked to other types of uveitis.

- Genetic predisposition. People who develop certain autoimmune diseases because of a gene alteration that affects their immune systems might also develop acute iritis. Diseases include ankylosing spondylitis, Reiter’s syndrome, inflammatory bowel disease (e.g. Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis) and psoriatic arthritis.

- Behcet’s disease. An uncommon cause of acute iritis in Western countries, this condition is also characterized by joint problems, mouth sores and genital sores.

- Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Chronic iritis can develop in children with this condition.

- Sarcoidosis. This autoimmune disease involves the growth of collections of inflammatory cells (granulomas) in areas of your body, including your eyes.

- Certain medications. Some drugs, such as the antibiotic rifabutin (Mycobutin) and the antiviral medication cidofovir, that are used to treat HIV infections can be a rare cause of iritis. Stopping these medications usually stops the iritis symptoms.

Risk factors for iritis

Your risk of developing iritis increases if you:

- Have a specific genetic alteration. People with a specific change in a gene that’s essential for healthy immune system function are more likely to develop iritis. This change is labeled HLA-B27 (usually associated with ankylosing spondylitis).

- Develop a sexually transmitted infection. Certain infections, such as syphilis or HIV/AIDs, are linked with a significant risk of iritis.

- Have a weakened immune system or an autoimmune disorder. This includes conditions such as ankylosing spondylitis and reactive arthritis.

- Smoke tobacco. Studies have shown that smoking contributes to your risk.

Iritis symptoms

Iritis can occur in one or both eyes. It usually develops suddenly, and can last six to eight weeks. Signs and symptoms of iritis include:

- Eye redness

- Discomfort or achiness in the affected eye

- Sensitivity to light (photophobia)

- Decreased vision

- Severe eye pain

- Eye soreness

- Excessive tearing

- Blurred vision

- Eye may appear swollen

- Uneven pupil sizes between the two eyes

Iritis that develops suddenly, over hours or days, is known as acute iritis. Symptoms that develop gradually or last longer than six weeks indicate chronic iritis.

Iritis diagnosis

When you visit an eye specialist (ophthalmologist), he or she will likely conduct a complete eye exam and gather a thorough health history.

Diagnosis of iritis includes a thorough examination and the recording of the patient’s complete medical history. Laboratory tests may be done to rule out an infection or an autoimmune disorder.

You may also need these tests:

- Blood tests

- An Eye Chart or Visual Acuity Test: This test measures whether a patient’s vision has decreased.

- A Funduscopic Exam: The pupil is widened (dilated) with eye drops and then a light is shown through with an instrument called an ophthalmoscope to noninvasively inspect the back, inside part of the eye.

- Ocular Pressure: An instrument, such a tonometer or a tonopen, measures the pressure inside the eye. Drops that numb the eye may be used for this test.

- A Slit Lamp Exam: A slit lamp noninvasively inspects much of the eye. It can inspect the front and back parts of the eye and some lamps may be equipped with a tonometer to measure eye pressure. A dye called fluorescein, which makes blood vessels easier to see, may be added to the eye during the examination. The dye only temporarily stains the eye.

- Analysis of fluid from the eye

- Photography to evaluate the retinal blood flow (angiography)

- Photography to measure the thickness of the retinal tissue and to determine the presence or absence of fluid in or under the retina.

If the ophthalmologist thinks an underlying condition may be the cause of your iritis, you may be referred to another doctor (e.g. rheumatologist) for a general medical examination, X-rays and laboratory tests to rule out specific causes. Sometimes, it’s difficult to find a specific cause for iritis. However, your doctor will try to determine whether your iritis is caused by an infection or another condition.

Iritis treatment

Iritis treatment is designed to preserve vision and relieve pain and inflammation. For iritis associated with an underlying condition, treating that condition also is necessary.

Most often, treatment for iritis involves:

- Steroid eyedrops. Glucocorticoid medications, given as eyedrops, reduce inflammation.

- Dilating eyedrops. Eyedrops used to dilate your pupil can reduce the pain of iritis. Dilating eyedrops also protect you from developing complications that interfere with your pupil’s function.

If your symptoms don’t clear up, or seem to worsen, your eye doctor might prescribe oral medications that include steroids or other anti-inflammatory agents, depending on your overall condition.

References- Gutteridge IF, Hall AJ. Acute anterior uveitis in primary care. Clinical and Experimental Optometry. 2007. 90(2):70-82.

- Augsburger JJ, Corrêa ZM. Chapter 19. Ophthalmic Trauma. In: Riordan-Eva P, Cunningham, Jr. ET, eds. Vaughan; Asbury’s General Ophthalmology. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:371-382

- Ramstead C, Ng M, Rudnisky CJ. Ocular injuries associated with Airsoft guns: a case series. Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 2008. 43(5):584-587

- Seth RK, Abedi G, Daccache AJ, Tsai JC. Cataract secondary to electrical shock from a Taser gun. Journal of Cataract and Refractive Surgery. 2007. 33(9):1664-1665

- Alexander KL, Dul MW, Lalle PA, Magnus DE. Onofrey B. Optometric Clinical Practice Guideline: Care of the Patient with Anterior Uveitis. St. Louis, MO: American Optometric Association; 1994:3-29.

- Reidy JJ. Section 08: External Disease and Cornea. Basic and Clinical Science Course. San Francisco, CA: American Academy of Ophthalmology; 2012: 363.

- Bartley GB, Liesegang TJ. Essentials of Ophthalmology. Philadelphia, PA: JB Lippincott Company; 1992:156-157

- Augsburger JJ, Corrêa ZM. Chapter 19. Ophthalmic Trauma. In: Riordan-Eva P, Cunningham, Jr. ET, eds. Vaughan & Asbury’s General Ophthalmology. 18th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2011:371-382

- Trevor-Roper PD, Curran PV. The Eye and Its Disorders. Boston, MA: Blackwell Scientific Publications; 1984:489-507

- Ehlers JP, Shah CP, Fenton GL, Hoskins EN. Chapter 03: Trauma. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams &; Wilkins; 2008:19-22

- Ehlers JP, Shah CP, Fenton GL, Hoskins EN. Chapter 03: Trauma. The Wills Eye Manual: Office and Emergency Room Diagnosis and Treatment of Eye Disease. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams; Wilkins; 2008:19-22