Light’s criteria

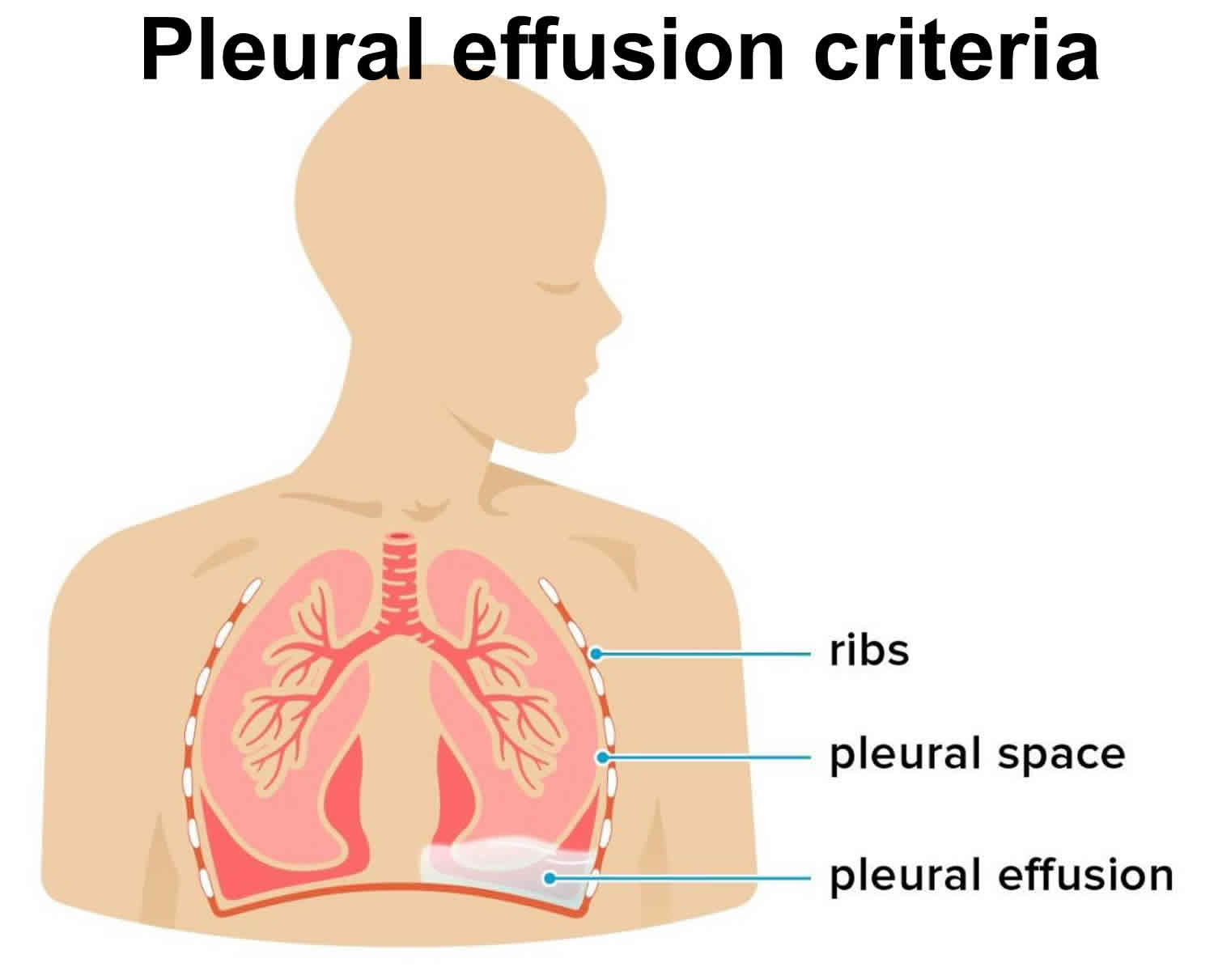

Light’s criteria is used to classify pleural effusion as a transudate or exudate 1. Pleural effusion is the accumulation of fluid in between the parietal and visceral pleura, called pleural cavity 2. Pleural effusion can occur by itself or can be the result of surrounding parenchymal disease like infection, malignancy or inflammatory conditions. Pleural effusion is one of the major causes of pulmonary mortality and morbidity 3.

Pleural fluid is exudate if one of the following Light’s criteria is present 4:

- Effusion protein/serum protein ratio greater than 0.5

- Effusion lactate dehydrogenase (LDH)/serum LDH ratio greater than 0.6

- Effusion LDH level greater than two-thirds the upper limit of the laboratory’s reference range of serum LDH

In the normal healthy adult, the pleural cavity has minimal fluid which acts a lubricant for the two pleural surfaces. The amount of pleural fluid is around at 0.1 ml/kg to 0.3 ml/kg and is constantly exchanged 2. Pleural fluid originates from the vasculature of parietal pleura surfaces and is absorbed back by lymphatics in the dependent diaphragmatic and mediastinal surfaces of parietal pleura. Hydrostatic pressure from the systemic vessels that supply the parietal pleura is thought to drive the interstitial fluid into the pleural space and hence has a lower protein content than serum. Accumulation of excess fluid can occur if there is excessive production or decreased absorption or both overwhelming the normal homeostatic mechanism. If pleural effusion is mainly due to Mechanisms that lead to pleural effusion mainly due to increased hydrostatic pressure are usually transudative, and leading to pleural effusion have altered the balance between hydrostatic and oncotic pressures (usually transudates), increased mesothelial and capillary permeability (usually exudates) or impaired lymphatic drainage 5.

Common causes of transudates include conditions which alter the hydrostatic or oncotic pressures in the pleural space like congestive left heart failure, nephrotic syndrome, liver cirrhosis, hypoalbuminemia leading to malnutrition and with the initiation of peritoneal dialysis.

Common causes of exudates include pulmonary infections like pneumonia or tuberculosis, malignancy, inflammatory disorders like pancreatitis, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, post-cardiac injury syndrome, chylothorax (due to lymphatic obstruction), hemothorax (blood in pleural space) and benign asbestos pleural effusion.

Some of the less common causes of pleural effusion are a pulmonary embolism which can be exudate or transudate, drug-induced (e.g., methotrexate, amiodarone, phenytoin, dasatinib, usually exudate), post-radiotherapy (exudate), esophageal rupture (exudate) and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (exudate).

Exudative pleural effusions

- Abdominal fluid: Abscess in tissues near lung, ascites, Meigs syndrome, pancreatitis

- Connective-tissue disease: Churg-Strauss disease, lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, Wegener granulomatosis

- Endocrine: Hypothyroidism, ovarian hyperstimulation

- Iatrogenic: Drug-induced, esophageal perforation, feeding tube in lung

- Infectious: Abscess in tissues near lung, bacterial pneumonia, fungal disease, parasites, tuberculosis

- Inflammatory: Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS), asbestosis, pancreatitis, radiation, sarcoidosis, uremia

- Lymphatic abnormalities: Chylothorax, malignancy, lymphangiectasia

- Malignancy: Carcinoma, lymphoma, leukemia, mesothelioma, paraproteinemia

Transudative pleural effusions

- Atelectasis: Due to increased negative intrapleural pressure

- Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leak into pleural space: Thoracic spine injury, ventriculoperitoneal (VP) shunt dysfunction

- Heart failure

- Hepatic hydrothorax

- Hypoalbuminemia

- Iatrogenic: Misplaced catheter into lung

- Nephrotic syndrome

- Peritoneal dialysis

- Urinothorax: Due to obstructive uropathy

Exceptions

These are processes that typically cause exudative effusions, but may cause transudative effusions.

- Amyloidosis

- Chylothorax

- Constrictive pericarditis

- Hypothyroid pleural effusion

- Malignancy

- Pulmonary embolism

- Sarcoidosis

- Superior vena cava obstruction

- Trapped lung

Leading causes of pleural effusion

- Congestive heart failure (transudate), incidence 500,000/year

- Pneumonia (exudate), incidence 300,000/year

- Cancer (exudate), incidence 200,000/year

- Pulmonary embolus (transudate or exudate), incidence 150,000/year

- Viral disease (exudate), incidence 100,000/year

- Coronary-artery bypass surgery (exudate), incidence 60,000/year

- Cirrhosis with ascites (transudate), incidence 50,000/year

Once the cause of pleural effusion is determined, management involves addressing the underlying cause. In cases of complex parapneumonic effusions or empyema, (pleural fluid pH less than 7.2 or presence of organisms) chest tube drainage is usually indicated along with antibiotics. Small-bore drains (10 G to 14 G) are equally effective as large bore drains for this purpose. If patients do not respond to appropriate antibiotics and adequate drainage, then thoracoscopic decortication or debridement may be necessary. Instillation of intrapleural fibrinolytics and DNAse may be used to improve drainage and in those who do not respond to sufficient antibiotic therapy and those who are not candidates for surgical intervention.

If a patient with malignant pleural effusion is not symptomatic, drainage is not always indicated unless an underlying infection is suspected. For malignant pleural effusions that require frequent drainage, options for management are pleurodesis (where the pleural space is obliterated either mechanically or chemically by inducing irritants into the pleural space) and tunneled pleural catheter placement 6.

References- Light RW, Macgregor MI, Luchsinger PC, Ball WC Jr. Pleural effusions: the diagnostic separation of transudates and exudates. Ann Intern Med. 1972 Oct. 77(4):507-13.

- Krishna R, Rudrappa M. Pleural Effusion. [Updated 2019 Feb 11]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448189

- Kugasia IAR, Kumar A, Khatri A, Saeed F, Islam H, Epelbaum O. Primary effusion lymphoma of the pleural space: Report of a rare complication of cardiac transplant with review of the literature. Transpl Infect Dis. 2019 Feb;21(1):e13005

- Ali HA, Lippmann M, Mundathaje U, Khaleeq G. Spontaneous hemothorax: a comprehensive review. Chest. 2008 Nov. 134(5):1056-65.

- Arnold DT, De Fonseka D, Perry S, Morley A, Harvey JE, Medford A, Brett M, Maskell NA. Investigating unilateral pleural effusions: the role of cytology. Eur. Respir. J. 2018 Nov;52(5).

- Bueno Fischer G, Teresinha Mocelin H, Feijó Andrade C, Sarria EE. When should parapneumonic pleural effusions be drained in children? Paediatr Respir Rev. 2018 Mar;26:27-30.