What is lymphoma

Lymphoma is a cancer of the lymphatic system 1, which is part of the body’s germ-fighting network (see Figures 1, 2 and 3). Lymphomas are cancers that start in white blood cells called lymphocytes. Lymphocytes are part of the body’s immune system. The lymphatic system includes the lymph nodes (lymph glands), spleen, thymus gland and bone marrow. Lymphoma can affect all those areas as well as other organs throughout the body. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) classification system identifies more than 90 different subtypes of lymphoma (see Table 2) 2.

There are many types of lymphoma. The main types of lymphoma are:

- Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Hodgkin disease): Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Hodgkin disease) is a cancer that starts in white blood cells called lymphocytes. Hodgkin’s lymphomas contain cells called Reed Sternberg cells. Treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma is different from other types of lymphoma. Hodgkin’s lymphoma is one of the most curable forms of cancer. The five-year relative survival rate is 94.3 percent for people who were less than 45 years old at diagnosis. Hodgkin lymphoma is most commonly diagnosed at 20 to 34 years of age; however, the median age at death is 68 because of the higher survival rate among younger patients 3.

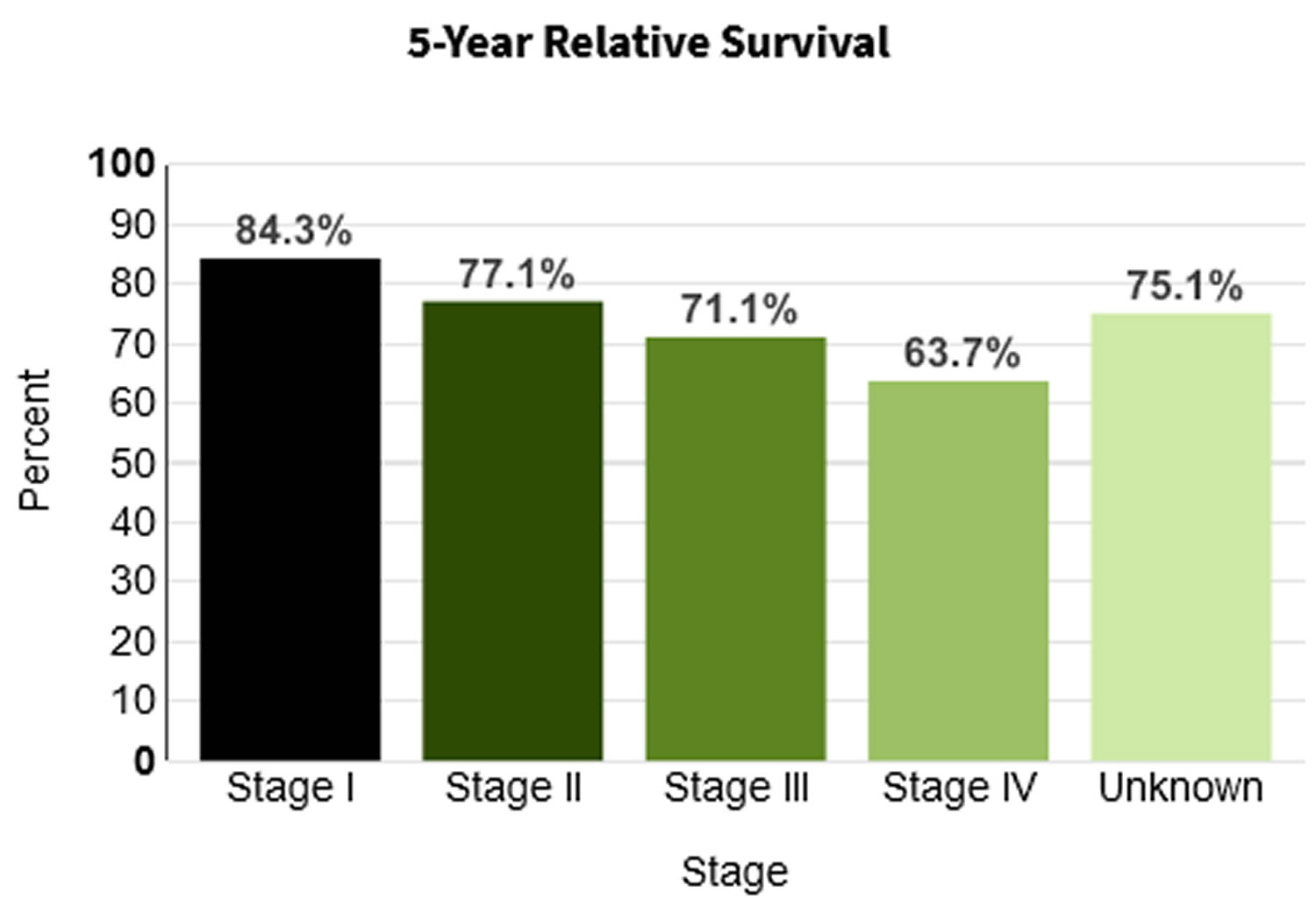

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL): Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) is a cancer that starts in cells called lymphocytes, which are part of the body’s immune system. About 90 percent of people diagnosed with lymphoma have non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL). Incidence of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is higher in men and whites, and it increases with age. The median age of patients at diagnosis of non-Hodgkin lymphoma is 67 years, and the median age at death is 76 4.

They behave, spread, and respond to treatment differently, so it’s important for you to know which one you have. Knowing which type of lymphoma you have is important because it affects your treatment options and your outlook (prognosis). If you aren’t sure which type you have, ask your doctor so you can get the right information.

What lymphoma treatment is best for you depends on your lymphoma type and its severity. Lymphoma treatment may involve chemotherapy, immunotherapy medications, radiation therapy or a bone marrow transplant.

Approximately 82,000 new U.S. patients are diagnosed with lymphoma annually, representing 4.7% of all new cancer cases in the United States 5. Tobacco use and obesity are major modifiable risk factors, with genetic, infectious, and inflammatory causes also contributing 5. Lymphoma typically presents as painless painless swelling in a lymph node, usually in the neck, armpit or groin; with systemic symptoms of fever, unexplained weight loss, and night sweats occurring in more advanced stages of the disease. An open lymph node biopsy is preferred for diagnosis. The Lugano classification system incorporates symptoms and the extent of the disease as shown on positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) to stage lymphoma, which is then used to determine treatment. Chemotherapy treatment plans differ between the main subtypes of lymphoma. Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is treated with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) with or without rituximab (R-CHOP), bendamustine, and lenalidomide. Hodgkin’s lymphoma is treated with combined chemotherapy with ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine), Stanford V (a chemotherapy regimen consisting of mechlorethamine, doxorubicin, vinblastine, vincristine, bleomycin, etoposide, and prednisone), or BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone) with radiotherapy. Subsequent chemotherapy toxicities include neuropathy, cardiotoxicity, and secondary cancers such as lung and breast, and should be considered in the shared decision-making process to select a treatment regimen.

In 2019 the five-year survival rate for non-Hodgkin lymphoma was 72.0%, and for Hodgkin lymphoma was 86.6% 6.

Once remission is achieved, patients need routine surveillance to monitor for complications and relapse, in addition to age-appropriate screenings recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Patients should receive a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine followed by a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine at least eight weeks later with additional age-appropriate vaccinations because lymphoma is an immunosuppressive condition. Household contacts should also be current with their immunizations.

Table 1. Common Lymphoma Subtypes with Incidence and Five-Year Survival

| Lymphoma subtype | Incidence per 100,000 | Five-year survival |

|---|---|---|

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 2.8 | 85.70% |

| Non-Hodgkin B-cell lymphomas | ||

| Burkitt | 0.4 | 64.10% |

| Diffuse large B cell | 7.2 | 63.20% |

| Follicular | 3.5 | 88.40% |

| Marginal zone | 2.2 | 90.30% |

| Precursor B cell | 1.5 | 68.90% |

| Non-Hodgkin T-cell and natural killer cell lymphomas | ||

| Mycosis fungoides | 0.6 | 90.90% |

| Peripheral T-cell | 1.2 | 58.40% |

Types of lymphoma

The World Health Organization’s (WHO) classification system identifies more than 90 different subtypes of lymphoma (Table 2) 2. The initial stratification is derived from B-cell, T-cell, or natural killer (NK) cell origin; however, they are ultimately each defined by morphology, immunopheno-type, genetic, molecular, and clinical features into 2:

- Chronic lymphocytic leukemia

- Cutaneous B-cell lymphoma

- Cutaneous T-cell lymphoma

- Hodgkin’s lymphoma (Hodgkin’s disease)

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL)

- Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia

Table 2. 2016 WHO classification of mature lymphoid, histiocytic, and dendritic neoplasms

| Mature B-cell neoplasms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Splenic diffuse red pulp small B-cell lymphoma |

| Hairy cell leukemia-variant |

|

| Waldenström macroglobulinemia |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Pediatric nodal marginal zone lymphoma |

|

| In situ follicular neoplasia* |

| Duodenal-type follicular lymphoma* |

|

|

|

|

| In situ mantle cell neoplasia* |

|

| Germinal center B-cell type* |

| Activated B-cell type* |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Mature T and NK neoplasms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Lymphomatoid papulosis |

| Primary cutaneous anaplastic large cell lymphoma |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Hodgkin lymphoma |

|

|

| Nodular sclerosis classical Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Lymphocyte-rich classical Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Mixed cellularity classical Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Lymphocyte-depleted classical Hodgkin lymphoma |

| Posttransplant lymphoproliferative disorders (PTLD) |

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Histiocytic and dendritic cell neoplasms |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Footnotes: *Changes from the 2008 classification. Provisional entities are listed in italics.

[Source 2 ]The Lymphatic System

To understand what lymphoma is, it helps to know about the lymph system (also known as the lymphatic system). The lymph system is part of the immune system, which helps fight infections and some other diseases. The lymphatic system plays a role in:

- fighting bacteria and other infections

- destroying old or abnormal cells, such as cancer cells

The lymphatic system also helps the flow of fluids in the body.

The lymph system is made up mainly of cells called lymphocytes, a type of white blood cell. There are 2 main types of lymphocytes:

- B lymphocytes (B cells): B lymphocytes (B cells) respond to an infection by changing into a different type of cell called a plasma cell. Plasma cells make proteins called antibodies (also called immunoglobulins) that help the body attack and kill disease-causing germs like bacteria and viruses.

- T lymphocytes (T cells): There are several types of T cells. Some T cells destroy germs or abnormal cells in the body. Other T cells help boost or slow the activity of other immune system cells.

- Natural killer (NK) cells, which attack virus-infected cells or tumor cells.

The lymphatic system is a vast collection of cells and biochemicals that travel in lymphatic vessels, and the organs and glands that produce them. The lymphatic system includes a network of vessels (like the arteries and veins that carry blood) that assist in circulating body fluids (a colorless liquid called lymph), so it is closely associated with your cardiovascular system. Lymphatic vessels transport excess fluid away from interstitial spaces in most tissues and return it to the bloodstream (Figure 3). This fluid carries food to the cells and bathes the body tissues to form tissue fluid. The fluid then collects waste products, bacteria, and damaged cells. It also collects any cancer cells if these are present. This fluid then drains into the lymph vessels. Without the lymphatic system, this fluid would accumulate in tissue spaces. Special lymphatic capillaries, called lacteals, are located in the lining of the small intestine. They absorb digested fats and transport them to the venous circulation.

The lymphatic system is a system of thin tubes and lymph nodes that run throughout the body. Lymph nodes are bean shaped glands. The thin tubes are called lymph vessels or lymphatic vessels. Tissue fluid called lymph circulates around the body in these vessels and flows through the lymph nodes.

The lymph system is an important part of your immune system. It plays a role in fighting bacteria and other infections and destroying old or abnormal cells, such as cancer cells.

The major sites of lymphoid tissue are:

- Lymph nodes: Lymph nodes are bean-sized collections of lymphocytes and other immune system cells throughout the body, including inside the chest, abdomen, and pelvis. They are connected to each other by a system of lymphatic vessels.

- Spleen: The spleen is an organ under the lower ribs on your left side. The spleen makes lymphocytes and other immune system cells. It also stores healthy blood cells and filters out damaged blood cells, bacteria, and cell waste.

- Bone marrow: The bone marrow is the spongy tissue inside certain bones. New blood cells (including some lymphocytes) are made there.

- Thymus: The thymus is a small organ behind the upper part of the breastbone and in front of the heart. Thymus is an organ in which T lymphocytes mature and multiply.

- Adenoids and tonsils: These are collections of lymphoid tissue in the back of your throat. They help make antibodies against germs that are breathed in or swallowed.

- Digestive tract: The stomach, intestines, and many other organs also have lymph tissue.

The lymphatic system has a second major function— it enables you to live in a world with different types of organisms. Some of them live in or on the human body and in some circumstances may cause infectious diseases. Cells and biochemicals of the lymphatic system launch both generalized and targeted attacks against “foreign” particles, enabling the body to destroy infectious agents. This immunity against disease also protects against toxins and cancer cells. When the immune response is abnormal, persistent infection, cancer, allergies, and autoimmune disorders may result.

The larger lymphatic vessels lead to specialized organs called lymph nodes. After leaving the lymph nodes, the vessels merge to form still larger lymphatic trunks.

Figure 1. Locations of major lymph nodes

Figure 2. Functions of lymph nodes in the lymphatic system

Figure 3. Schematic representation of lymphatic vessels transporting fluid from interstitial spaces to the bloodstream. Depending on its origin, lymph enters the right or left subclavian vein.

Lymphoma signs and symptoms

Signs and symptoms of lymphoma include:

- Enlarged lymph nodes that can occur in any part of the body but most often occur in the neck, armpit or groin

- Fatigue

- Fever

- Night sweats

- Shortness of breath

- Weight loss

- Itchy skin

The most common early sign of lymphoma is painless enlargement of one or more lymph nodes (also known as painless adenopathy). The enlarged lymph nodes can wax and wane over years in indolent presentations or involve rapidly progressive enlarged lymph nodes in more aggressive subtypes. Hodgkin’s lymphoma typically appears in the supradiaphragmatic lymph nodes. Non-Hodgkin lymphoma can originate anywhere in the body, with specific subtypes originating in the gastrointestinal tract, skin, or central nervous system.

Systemic symptoms of fever, unexplained weight loss, and night sweats occur in a subset of patients with more advanced disease. Lymphoma spreads to extranodal sites by direct invasion or by spreading through blood to the spleen, liver, lungs, or bone marrow 7, 8. High-grade lymphomas can present as oncologic emergencies because of the structural compression from the enlarging tumor, including superior vena cava syndrome, malignant epidural spinal cord compression, or malignant pericardial effusion 9. Paraneoplastic syndrome is a group of symptoms that may develop when substances released by some cancer cells disrupt the normal function of surrounding cells and tissue. Paraneoplastic syndromes are rare with lymphoma, occurring as paraneoplastic cerebellar degeneration in Hodgkin lymphoma and as dermatomyositis and polymyositis in Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphomas 10.

What Causes lymphoma

Doctors aren’t sure what causes lymphoma. Lymphoma begins when a disease-fighting white blood cell called a lymphocyte develops a mutation in its genetic code. The mutation tells the cell to multiply rapidly, causing many diseased lymphocytes that continue multiplying.

The mutations also allow the cells to go on living when other cells would die. This causes too many diseased and ineffective lymphocytes in your lymph nodes and causes the lymph nodes to swell.

Risk factors for lymphoma

Factors that may increase your risk of lymphoma include:

- Increasing age. Your risk of lymphoma increases as you age, though it can occur at any age. Some types of lymphoma are more common in young adults.

- Being male. Lymphoma is more common in men than it is in women.

- Having an impaired immune system. Lymphoma is more common in people with immune system diseases or in people who take drugs that suppress their immune systems.

- Developing certain infections. Some infections are associated with an increased risk of lymphoma, including Epstein-Barr virus and Helicobacter pylori infection.

Tobacco use 11 and obesity (body mass index [BMI] of 30 kg/m² or higher) 12 are major modifiable risk factors, with genetic, infectious, and inflammatory causes also contributing 5. Breast implants and long-term pesticide exposure have also been associated with non-Hodgkin lymphoma 13.

First-degree relatives of patients with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin lymphoma have a respective 1.7-fold and 3.1-fold increased risk of developing lymphoma 5. A family history of a specific subtype of lymphoma is associated with developing that same subtype 14. There are three main mechanisms through which infection increases lymphoma risk: direct transformation of lymphocytes, immunosuppression, and chronic antigenic stimulation 15. Rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren syndrome, dermatomyositis, and celiac disease are inflammatory conditions that increase the risk of lymphoma through disease-specific causes and the chronic use of immunosuppressive medications 16.

Lymphoma diagnosis

Tests and procedures used to diagnose lymphoma include:

- Physical exam. Your doctor may examine your body to look for signs of enlarged lymph nodes.

- Removing a lymph node for testing. Your doctor may recommend a lymph node biopsy procedure to remove all or part of a lymph node for laboratory testing. Advanced tests can determine if lymphoma cells are present and what types of cells are involved.

- Blood tests. Blood tests to count the number of cells in a sample of your blood can give your doctor clues about your diagnosis.

- Removing a sample of bone marrow for testing. A bone marrow biopsy and aspiration procedure involves inserting a needle into your hipbone to remove a sample of bone marrow. The sample is analyzed to look for lymphoma cells.

- Imaging tests. Imaging tests may be used to look for signs of lymphoma in other areas of your body. Tests may include CT, MRI and positron emission tomography (PET).

Other tests and procedures may be used depending on your situation. Research shows that having a biopsy sample reviewed by an expert pathologist improves the chances for an accurate diagnosis. Consider getting a second opinion from a specialist who can confirm your diagnosis.

The diagnosis of lymphoma is made using an open lymph node biopsy, based off morphology, immunohistochemistry, and flow cytometry 17. Although fine-needle aspiration and core needle biopsy are often part of the initial evaluation of any enlarged lymph node, neither will provide adequate tissue for the diagnosis of lymphoma because of the need to verify Hodgkin lymphoma via the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells 18.

Lymphoma Staging

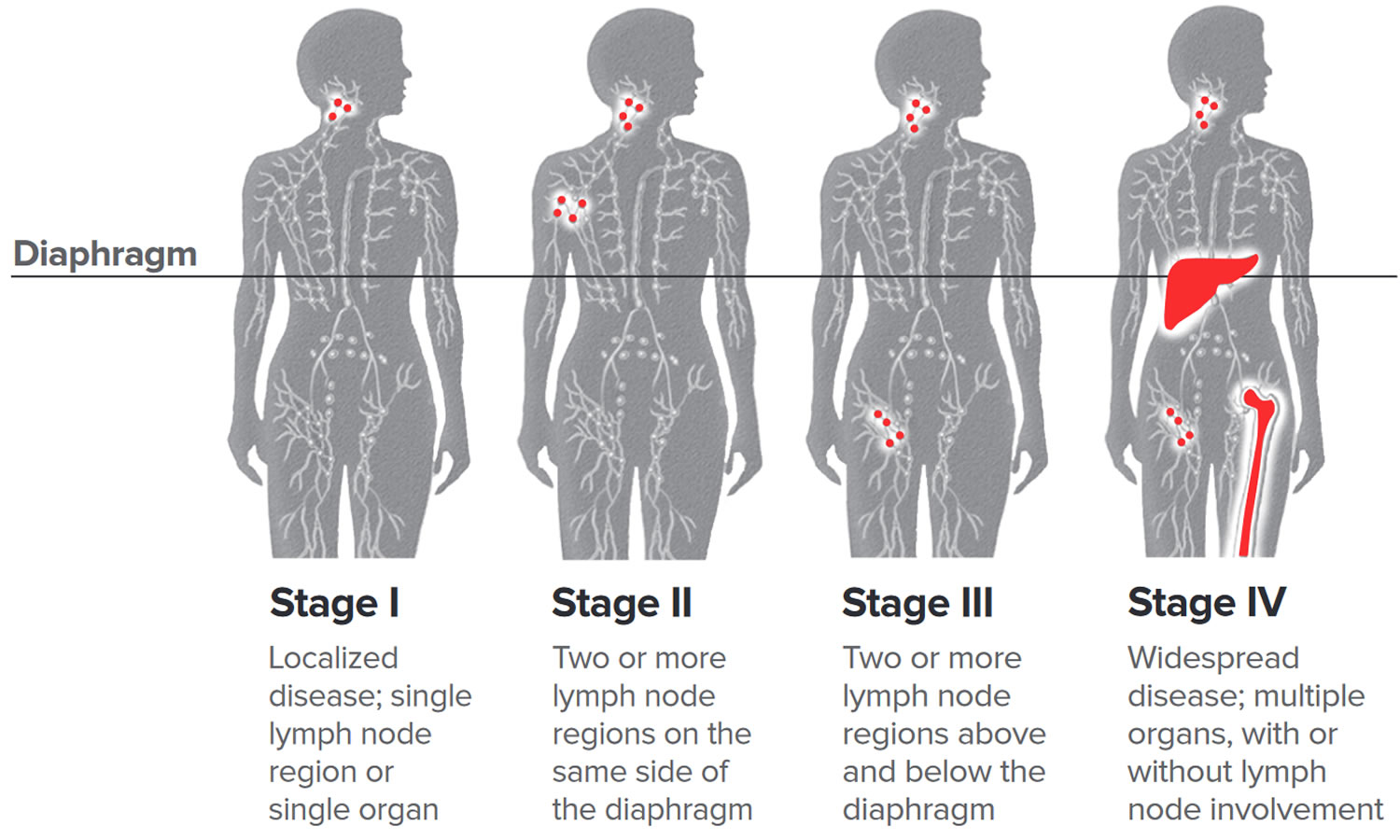

The Ann Arbor staging system was initially developed in 1971 for Hodgkin lymphoma and was later adapted for non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The Lugano classification system further modified staging by incorporating positron emission tomography/computed tomography (PET-CT) results to determine the staging of the lymphoma (Table 3) 19. PET-CT is used for fluorodeoxyglucose-avid lymphoma subtypes, with symptoms alone being used for staging the remaining subtypes. The new staging system incorporates two symptom-based classifications: A (absence of symptoms) and B (presence of fever, weight loss, and night sweats) for Hodgkin lymphoma. A bone marrow biopsy is now recommended only for diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with a negative PET-CT result 19.

Table 3. Lugano Classification for Lymphoma Staging

| Stage* | Description of disease from positron emission tomography/computed tomography results |

|---|---|

| I | Single nodal group or single extralymphatic lesion |

| II† | Multiple nodal groups on same side of diaphragm or with limited contiguous extralymphatic involvement |

| III | Multiple nodal groups on both sides of the diaphragm; may involve the spleen |

| IV | Noncontiguous extralymphatic involvement |

Footnotes:

* Staging for Hodgkin lymphoma is further subdivided for systemic symptoms; A for absence of symptoms or B for fevers > 101.3°F (38.5°C), drenching night sweats, or 10% (of body weight) unintentional weight loss over the past six months.

† Stage II may also be classified as bulky disease (> 10-cm mass), which may be treated as limited or advanced disease based on several prognostic factors.

[Source 19 ]Lymphoma treatment

Your lymphoma treatment options will depend on your type of lymphoma, its aggressiveness, stage, your overall health, and your treatment goals. The goal of lymphoma treatment is to destroy as many cancer cells as possible and bring the disease into remission.

Lymphoma treatments include:

- Active surveillance. Some forms of lymphoma are very slow growing. You and your doctor may decide to wait to treat your lymphoma when it causes signs and symptoms that interfere with your daily activities. Until then, you may undergo periodic tests to monitor your condition.

- Chemotherapy. Chemotherapy is a drug treatment that uses chemicals to kill cancer cells. Chemotherapy is usually administered through a vein, but can also be taken as a pill, depending on the specific drugs you receive.

- Hodgkin’s lymphoma is treated with combined chemotherapy with ABVD (doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine), Stanford V (a chemotherapy regimen consisting of mechlorethamine, doxorubicin, vinblastine, vincristine, bleomycin, etoposide, and prednisone), or BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone) with radiotherapy.

- Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NHL) is treated with CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) with or without rituximab (R-CHOP), bendamustine, and lenalidomide.

- Other drug therapy. Other drugs used to treat lymphoma include targeted drugs that focus on specific abnormalities within your cancer cells that allow them to survive. Immunotherapy drugs use your immune system to kill cancer cells. A specialized treatment called chimeric antigen receptor (CAR)-T cell therapy takes your body’s germ-fighting T cells, engineers them to fight cancer and infuses them back into your body.

- Radiation therapy. Radiation therapy uses powerful beams of energy, such as X-rays and protons, to kill cancer cells.

- Bone marrow transplant. Bone marrow transplant, also known as a stem cell transplant, involves using high doses of chemotherapy and radiation to suppress your bone marrow. Then healthy bone marrow stem cells from your body or from a donor are infused into your blood where they travel to your bones and rebuild your bone marrow.

Treatment of lymphoma consists of chemotherapy alone or in combination with radiotherapy 20. Radiotherapy alone is not recommended 21. Toxicity from radiotherapy can lead to serious long-term complications such as secondary cancers in the irradiated area, including breast or lung cancers 21. Additionally, patients receiving chemotherapy can subsequently develop breast or lung cancers, melanoma, or acute myeloid leukemia 22. Patients who are older than 60 years at diagnosis have worse outcomes, regardless of the staging. The National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) recommends avoiding certain chemotherapeutic agents in patients older than 60 years. The physician should focus on shared decision-making when discussing treatment options with all patients, but particularly for those older than 60 years, including whether the patient should pursue treatment 21.

The standard treatment for Hodgkin’s lymphoma is ABVD (doxorubicin [Adriamycin], bleomycin, vinblastine [Velban], and dacarbazine), but other regimens such as the Stanford V (doxorubicin, vinblastine, mechlorethamine, etoposide [Toposar], vincristine, bleomycin, and prednisone) and escalated-BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine [Matulane], and prednisone) can be used 20. Treatment for non-Hodgkin lymphoma varies depending on the histology, but often uses treatments such as CHOP (cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone) with or without rituximab (Rituxan; R-CHOP), a monoclonal antibody specific for CD20-positive B lymphocytes 23. Other medications such as bendamustine (Bendeka), an alkylating agent, and lenalidomide (Revlimid) are also used in many non-Hodgkin lymphoma treatments 24, 25. Common complications of these therapies are listed in Table 4 below.

A Cochrane review that examined seven trials consisting of more than 2,500 adult patients with early Hodgkin lymphoma concluded that the use of combined therapy could increase progression-free survival with little difference between the overall survival rates 26. Short-term complications from radiotherapy include nausea, vomiting, headaches, fatigue, and dermatitis. Radiotherapy can also lead to long-term complications, including cardiac and pulmonary toxicity, hypothyroidism, or breast or lung cancers 27. Radiotherapy can be avoided in patients with stage IA or IIA lymphoma without bulky disease (see Table 3 Lugano Classification for Lymphoma Staging above) 21.

Table 4. Common Chemotherapy Regimens for Lymphoma and their complications

| Therapy | Regimen | Short-term complications | Long-term complications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | |||

| ABVD | Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) | Nausea/vomiting Alopecia Neutropenia Neuropathy Bleomycin-induced pulmonary toxicity | Cardiotoxicity (heart failure) Neuropathy Pulmonary fibrosis Increased risk of myocardial infarction |

| Bleomycin | |||

| Vinblastine (Velban) | |||

| Dacarbazine | |||

| Stanford V | Doxorubicin | Nausea/vomiting Fatigue Pulmonary toxicity Neuropathy | Neuropathy Pulmonary fibrosis Cardiotoxicity Rarely solid secondary malignancies of breast, lung, and skin |

| Vinblastine | |||

| Mechlorethamine | |||

| Etoposide (Toposar) | |||

| Vincristine | |||

| Bleomycin | |||

| Prednisone | |||

| Escalated-BEACOPP | Bleomycin | Anemia Leukopenia Thrombocytopenia Nausea/vomiting Infection Disulfiram reaction between ethanol and procarbazine | Acute myeloid leukemia Sterility/infertility |

| Etoposide | |||

| Doxorubicin (Adriamycin) | |||

| Cyclophosphamide | |||

| Vincristine (Oncovin) | |||

| Procarbazine (Matulane) | |||

| Prednisone | |||

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | |||

| CHOP | Cyclophosphamide | Heart failure Constipation Hyperglycemia Neuropathy | Cardiomyopathy Myelosuppression Neuropathy |

| Doxorubicin | |||

| (Hydroxydaunorubicin) | |||

| Vincristine (Oncovin) | |||

| Prednisone | |||

| R-CHOP | Rituximab (Rituxan) + CHOP | Reactivate hepatitis B infection | Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy |

Immunizations

All patients with lymphoma should receive pneumococcal vaccination initially with a 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (Prevnar 13), followed at least eight weeks later by a 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (PPSV23; Pneumovax 23) and then another PPSV23 at least five years later 28. Patients receiving anti–B-cell antibodies should not receive annual influenza vaccination, and administration of live vaccines is contraindicated during chemotherapy. Routine vaccinations recommended by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) should resume, including any recommended inactivated or live vaccines three months after chemotherapy or six months after anti–B-cell antibody therapy 29. Patients receiving a hematopoietic stem cell transplant should receive a series of three doses of Haemophilus influenzae type B vaccine starting six to 12 months after a successful transplant. Household contacts should receive appropriate CDC-recommended immunizations 30.

Treatment follow-up

PET-CT scans, and subsequent Deauville scoring (Table 5), should be used to assess the response to chemotherapy in non-Hodgkin and Hodgkin lymphoma 21, 24, 25, 31. A score of 3 or less is considered complete remission in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and should conclude the current treatment course. A score of 4 or 5 is an indicator to consider escalating therapy 21. Patients with Hodgkin lymphoma with a Deauville score of 1 or 2 have been shown to have similar progression and mortality outcomes between radiotherapy and no further treatment 26. Patients who receive a score of 3 or 4 should receive additional chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, and a score of 5 indicates the need for a biopsy (excisional or core needle) in addition to chemotherapy and radiotherapy 21. A positive biopsy should be considered refractory disease 21.

Table 5. Deauville Score for Assessing PET-CT Scans

| PET-CT finding | Score |

|---|---|

| No FDG uptake related to lymphoma | 1 |

| FDG uptake at lymphoma site is ≤ mediastinum FDG uptake | 2 |

| FDG uptake at lymphoma site is > mediastinum FDG uptake but < liver FDG uptake | 3 |

| FDG uptake at lymphoma site is > liver FDG uptake at any site | 4 |

| FDG uptake at lymphoma site is substantially > liver FDG uptake or new FDG uptake sites found | 5 |

Abbreviations: FDG = fluorodeoxyglucose; PET-CT = positron emission tomography/computed tomography

[Source 32 ]Lymphoma Surveillance

Patients who have achieved remission need routine surveillance to monitor for complications and relapse, as well as age-appropriate screenings recommended by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force 33. Complications of lymphoma treatment include secondary malignancies (e.g., breast, lung, skin, colon), cardiac disease, infertility, and endocrine, neurologic, and psychiatric dysfunctions. Current National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines outline specific monitoring parameters for follow-up and prevention of secondary disease (Table 6) 21. The extent and frequency of follow-up specifically depend on the histologic subtype of lymphoma. Patients should follow up with an oncologist every three to six months for the first two years, every six to 12 months until year 3, then annually thereafter. After five years of being cancer free, the patient can be transitioned to a primary care physician 34.

If a patient is asymptomatic, routine surveillance imaging does not improve outcomes or provide a clinical benefit 34, 35. Surveillance imaging should be used in patients who have reported symptoms or who are at high risk of relapse in a place that would not be easily examined, and who would be candidates for treatment. However, National Comprehensive Cancer Network imaging guidelines for lymphoma surveillance state that it is acceptable to perform chest radiography or CT of the chest every six to 12 months for the first two years and then yearly for the next three to five years posttreatment 36. Surveillance imaging with PET-CT scans following complete remission is not recommended 34. Disease marker research is ongoing, examining minimal residual disease measurements, a polymerase chain reaction–based method that looks at identifying tumor-specific DNA sequences 35.

Table 6. Lymphoma Surveillance for up to Five Years Post-Treatment

| Cancer screening | Laboratory screening | Cardiac screening | Counseling | Immunizations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Breast: annual screening mammography starting at age 40; history of chest or axilla radiation: start eight to 10 years after treatment or at age 40, whichever comes first; consider annual breast magnetic resonance imaging if chest radiation was received between ages 10 and 30; consider referral to breast subspecialist to discuss possible chemoprevention | Complete blood count, fasting blood glucose, and comprehensive metabolic panel annually | Annual blood pressure screening, lifestyle modification, and treatment of obesity, hypertension, and tobacco use | Annual depression screening | Age-appropriate immunizations per the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention schedule, including annual influenza vaccine; resume live vaccines at least three months after completion of chemotherapy |

| Routine surveillance tests for cervical, colorectal, lung, and prostate cancers per the USPSTF guidelines | Lipid profile per the USPSTF guidelines | Consider stress test and/or echocardiography at 10-year intervals (frequency of testing based on findings and other associated risk factors) | Neurocognitive impairment screening for any patient who is high risk (e.g., history of brain radiation or intrathecal treatment) | PCV13 (Prevnar 13), followed by PPSV23 (Pneumovax 23) at least eight weeks later and again at least five years later |

| Thyroid-stimulating hormone annually if neck irradiation | Carotid ultrasonography every 10 years if neck irradiation | Infertility: consider reproductive endocrinologist referral | Haemophilus influenzae type b: three doses following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation |

Abbreviations: PCV13 = 13-valent pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; PPSV23 = 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine; USPSTF = U.S. Preventive Services Task Force.

[Source 5 ]Lymphoma coping and support

A lymphoma diagnosis can be overwhelming and scary. With time you’ll find ways to cope with the distress and uncertainty of cancer. Until then, you may find it helps to:

- Learn enough about lymphoma to make decisions about your care. Ask your doctor about your lymphoma, including your type, your treatment options and, if you like, your prognosis. As you learn more about lymphoma, you may become more confident in making treatment decisions.

- Keep friends and family close. Keeping your close relationships strong will help you deal with your lymphoma. Friends and family can provide the practical support you’ll need, such as helping take care of your house if you’re in the hospital. And they can serve as emotional support when you feel overwhelmed by cancer.

- Find someone to talk with. Find a good listener with whom you can talk about your hopes and fears. This may be a friend or family member. The concern and understanding of a counselor, medical social worker, clergy member or cancer support group also may be helpful.

Ask your doctor about support groups in your area. You might also contact a cancer organization such as the National Cancer Institute (https://www.cancer.org) or the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society (https://www.lls.org).

Lymphoma relapse

Relapse rates for non-Hodgkin lymphoma are variable and based on the specific subtype. The most common subtype, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, has a 40% lifetime relapse rate 37. Lifetime relapse in Hodgkin lymphoma occurs in 10% to 15% of patients with early stage disease and 40% of patients with advanced stage disease 38.

Lymphoma prognosis

The International Prognostic Index is used broadly for all subtypes of non-Hodgkin lymphoma 39 and the International Prognostic Score is used for Hodgkin lymphoma 40.

Table 7. Lymphoma International Prognostic Index

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | Hodgkin lymphoma |

|---|---|

| International Prognostic Index | International Prognostic Score |

| Criteria | Criteria |

| Age > 60 | Age > 45 |

| Elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase | Male sex |

| Eastern Cooperative Oncology | Serum albumin concentration < 4.0 g per dL (40 g per L) |

| Group performance status ≥ 2* | Hemoglobin concentration < 10.5 g per dL (105 g per L) |

| Ann Arbor stage III or IV disease† | |

| Extranodal sites > 1 | Ann Arbor stage IV disease† Leukocytosis (≥ 15,000 μL [15 × 109 white blood cells per L]) Lymphopenia (< 600 lymphocytes per μL [0.6 × 109 per L], or < 8% of total white blood cell count) |

| Total score____ | Total score____ |

| Five-year overall survival rate based on number of criteria from International Prognostic Index/Score | |

| Score 0 or 1 = 73% | Score 0 = 89% |

| Score 2 = 51% | Score 1 = 90% |

| Score 3 = 43% | Score 2 = 81% |

| Score 4 or 5 = 26% | Score 3 = 78% |

| Score 4 = 61% | |

| Score ≥ 5 = 56% | |

Footnote: Each criterion = 1 point.

* Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status: 0 = fully active, 1 = ambulatory but restricted to light work, 2 = ambulatory but unable to carry out activities, 3 = limited self-care only, 4 = bedridden, 5 = dead.

† Ann Arbor stage III = multiple nodal groups on both sides of the diaphragm, may involve the spleen; stage IV = noncontiguous extralymphatic involvement.

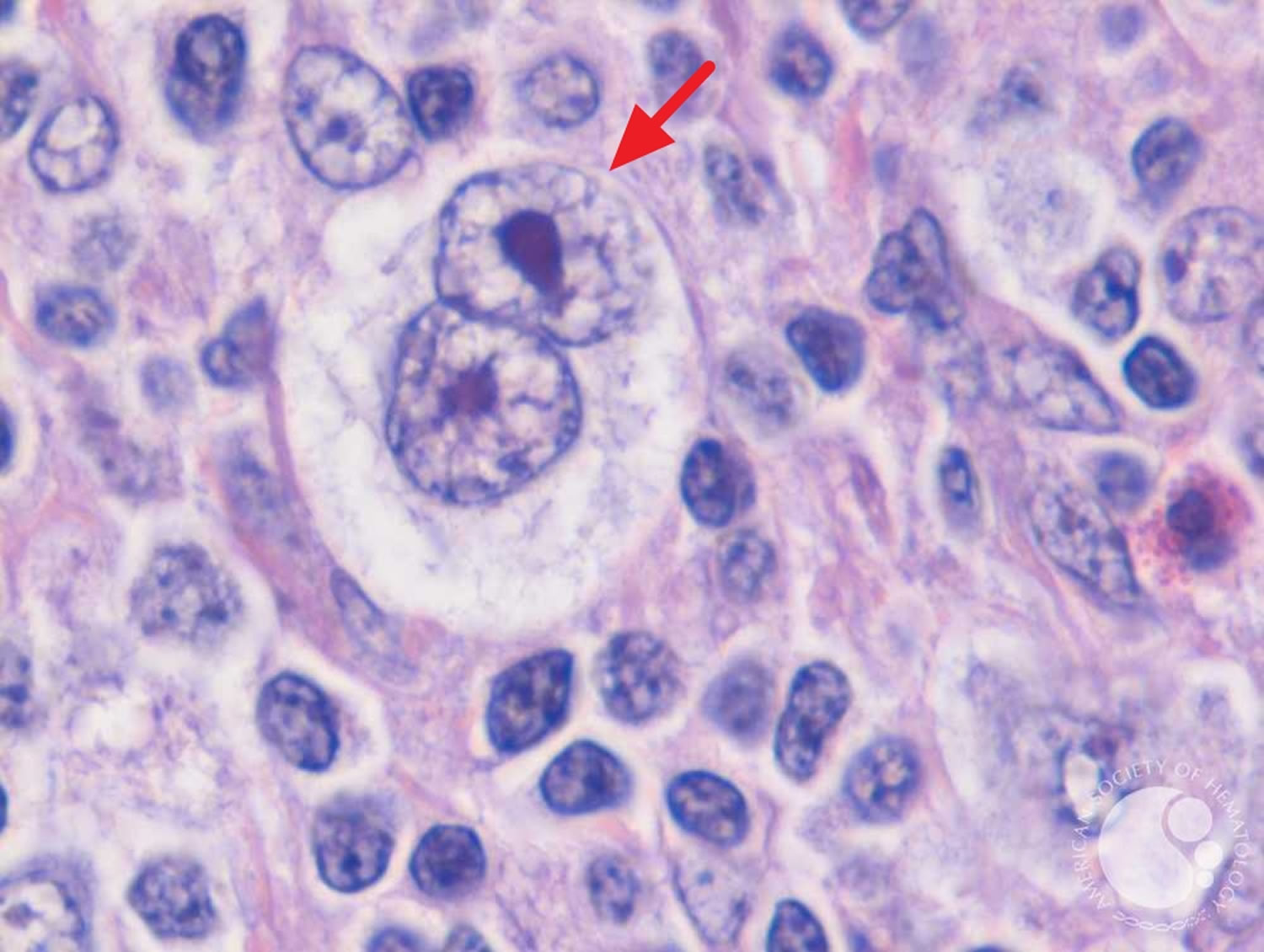

Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma also called Hodgkin’s disease is an uncommon cancer that develops in the lymphatic system that is marked by the presence of a type of cell called the Reed-Sternberg cell (see Figure 1). The two major types of Hodgkin lymphoma are classic Hodgkin lymphoma and nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma 41. Classical Hodgkin lymphoma accounts for approximately 95% of all Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and it is further subdivided into four subgroups: nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma (NSHL), lymphocyte-rich Hodgkin lymphoma (LRHL), mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma (MCHL), and lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma (LDHL) 42. Although Hodgkin lymphoma can start almost anywhere, most often it starts in lymph nodes in the upper part of the body. The most common sites are in the chest, neck, or under the arms. Signs and symptoms of Hodgkin lymphoma include painless, swollen lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), an enlarged spleen, fever, weight loss, fatigue, and night sweats.

Hodgkin lymphoma is named after Dr. Thomas Hodgkin who, in 1832, described several cases of people with symptoms of a cancer involving the lymph nodes. The disease was called “Hodgkin’s disease” until it was officially renamed “Hodgkin lymphoma” in the late 20th century.

Hodgkin lymphoma is distinguished from other types of lymphoma primarily by the presence of two types of cells, referred to as Hodgkin cells and Reed-Sternberg cells, named after the scientists who first identified them. Reed-Sternberg cells are large, abnormal B lymphocytes that often have more than one nucleus and an owl-like appearance (Figure 1). Hodgkin cells are larger than normal lymphocytes, but smaller than Reed-Sternberg cells. These differences can be observed under a microscope and further identified by special pathology tests. This is important information that helps doctors determine a patient’s Hodgkin lymphoma subtype.

Hodgkin lymphoma starts when an abnormal change to the DNA of a white blood cell called a lymphocyte causes it to become a lymphoma cell that, if untreated, results in the uncontrolled growth of cancerous lymphocytes.

- These cancerous cells crowd out normal white cells, and the immune system can’t guard against infection effectively.

- Lymphoma cells grow and form masses, usually in the lymph nodes, located throughout our bodies in the lymphatic system.

- Lymphoma cells can also gather in other areas of the body where lymphoid tissue is found.

- Hodgkin lymphoma is distinguished from other types of lymphoma by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells (named for the scientists who first identified them). Other cells associated with the disease are called Hodgkin cells.

Hodgkin lymphoma most often spreads through the lymph vessels from lymph node to lymph node. Rarely, late in the disease, it can invade the bloodstream and spread to other parts of the body, such as the liver, lungs, and/or bone marrow.

The American Cancer Society’s estimates for Hodgkin disease (Hodgkin’s lymphoma) in the United States for 2022 are 43, 44:

- New cases: About 8,540 new cases (4,570 in males and 3,970 in females)

- Deaths: About 920 deaths (550 males and 370 females)

- 5-Year Relative Survival: 89.1%. Relative survival is an estimate of the percentage of patients who would be expected to survive the effects of their cancer. It excludes the risk of dying from other causes. Because survival statistics are based on large groups of people, they cannot be used to predict exactly what will happen to an individual patient. No two patients are entirely alike, and treatment and responses to treatment can vary greatly.

- Percentage of All Cancer Deaths: 0.2%.

- Rate of New Cases and Deaths per 100,000: The rate of new cases of Hodgkin lymphoma was 2.6 per 100,000 men and women per year. The death rate was 0.3 per 100,000 men and women per year. These rates are age-adjusted and based on 2015–2019 cases and deaths.

- Lifetime Risk of Developing Cancer: Approximately 0.2 percent of men and women will be diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma at some point during their lifetime, based on 2017–2019 data.

- In 2019, there were an estimated 218,740 people living with Hodgkin lymphoma in the United States.

Both children and adults can develop Hodgkin lymphoma, but it is most common in early adulthood (especially in a person’s 20s). The risk of Hodgkin lymphoma rises again in late adulthood (after age 55). Overall, the average age of people when they are diagnosed is 39.

Hodgkin lymphoma is rare in children younger than 5 years of age. About 10% to 15% of cases are diagnosed in children and teenagers ages 15 to 19 years.

Survival rates have improved in the past few decades, largely due to advances in treatment. More than 75% of all newly diagnosed patients with adult Hodgkin lymphoma can be cured with combination chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy 45. The 5-year relative survival rate for all patients diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma is now about 89.1%, and the 10-year relative survival rate is about 80%. Certain factors such as the stage (extent) of Hodgkin lymphoma and a person’s age affect these rates.

Many types of Hodgkin’s lymphoma exist, including rare forms that are difficult for inexperienced pathologists to identify. Accurate diagnosis and staging are key to developing a treatment plan. Research shows that review of biopsy tests by pathologists who aren’t experienced with lymphoma results in a significant proportion of misdiagnoses. Get a second opinion from a specialist if needed.

Figure 4. Reed Sternberg cells seen in classical Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Footnote: Reed-Sternberg cells are large, abnormal lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) that may contain more than one nucleus. Reed-Sternberg cells are found in people with Hodgkin lymphoma. Reed-Sternberg cells are also called Hodgkin and Reed-Sternberg cells.

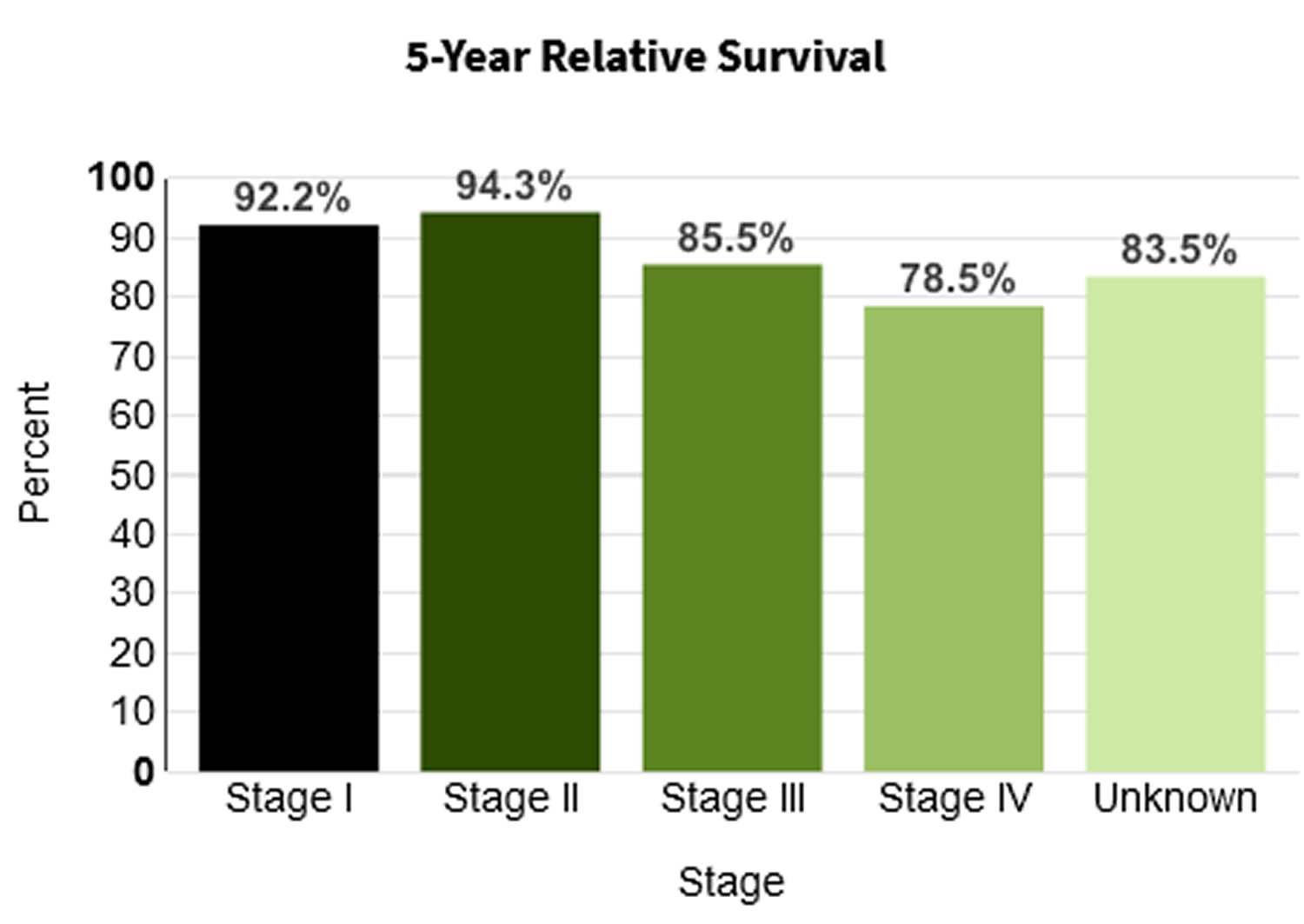

Survival rates for Hodgkin’s lymphoma

The numbers below come from the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program 46 database, looking at more than 8,000 people diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma between 1988 and 2001.

- The 5-year survival rate for people with stage I Hodgkin lymphoma is about 92.2%.·

- For stage II Hodgkin lymphoma, the 5-year survival rate is about 94.3%.

- The 5-year survival rate for stage III Hodgkin lymphoma is about 85.5%.

- Stage IV Hodgkin lymphoma has a 5-year survival rate of about 78.5%.

Based on data from SEER (Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results Program at the National Cancer Institute) 2011-2017, percent surviving 5 Years is 88.3% 47.

Figure 5. 5-year relative survival rates for Hodgkin lymphoma

Footnote: A relative survival rate compares people with the same type and stage of Hodgkin’s lymphoma to people in the overall population. For example, if the 5-year survival rate for a specific stage of Hodgkin lymphoma is 88.3%, it means that people who have that cancer are, on average, about 88.3% as likely as people who don’t have that cancer to live 5 years after being diagnosed.

- These numbers apply only to the stage of the cancer when it is first diagnosed. They do not apply later on if the cancer grows, spreads, or comes back after treatment.

- These numbers don’t take everything into account. Survival rates are grouped based on how far the cancer has spread, but your age, overall health, how well the cancer responds to treatment, and other prognostic factors (described below) can also affect your outlook.

- People now being diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma may have a better outlook than these numbers show. Treatments improve over time, and these numbers are based on people who were diagnosed and treated at least five years earlier.

Hodgkin’s lymphoma Survival by Stage

Cancer stage at diagnosis, which refers to extent of a cancer in the body, determines treatment options and has a strong influence on the length of survival. In general, if the cancer is found only in the part of the body where it started it is localized (sometimes referred to as stage 1). If it has spread to a different part of the body, the stage is regional or distant. For Hodgkin lymphoma, 15.6% are diagnosed at the local stage. The 5-year survival for localized Hodgkin lymphoma is 92.2%.

Remember, these survival rates are only estimates – they can’t predict what will happen to any individual person. We understand that these statistics can be confusing and may lead you to have more questions. Talk to your doctor to better understand your specific situation.

Other prognostic factors

Along with the stage of the Hodgkin lymphoma, other factors can affect a person’s prognosis (outlook). For example, having some factors means the lymphoma is likely to be more serious:

- Having B symptoms or bulky disease

- Being older than 45

- Being male

- Having a high white blood cell count (above 15,000)

- Having a low red blood cell count (hemoglobin level below 10.5)

- Having a low blood lymphocyte count (below 600)

- Having a low blood albumin level (below 4)

- Having a high erythrocyte sedimentation rate, or ESR (over 30 in someone with B symptoms, or over 50 for someone without B symptoms)

Some of these factors are used to help divide stage I or II Hodgkin lymphoma into favorable and unfavorable groups, which can affect how intense the treatment needs to be (see Hodgkin’s lymphoma staging below).

Types of Hodgkin’s lymphoma

The World Health Organization (WHO) divides Hodgkin lymphoma into two main subtypes. They are:

- Classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL)

- Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL)

Classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) is characterized by the presence of Reed-Sternberg cells. Nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) is characterized by the presence of lymphocyte-predominant cells, sometimes termed “popcorn cells,” and Reed-Sternberg cells are not found.

It’s important to know your subtype since it plays a large part in determining the type of treatment you’ll receive.

Classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cHL) accounts for about 95% of all cases of Hodgkin’s lymphomas in developed countries 48.

The cancer cells in Classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cHL) are called Reed-Sternberg cells. These cells are usually an abnormal type of B lymphocyte. Enlarged lymph nodes in people with Classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma (cHL) usually have a small number of Reed-Sternberg cells and a large number of surrounding normal immune cells. These other immune cells make up most of the enlarged lymph nodes.

Classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma has 4 subtypes:

- Nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma (NSCHL): This is the most common type of Hodgkin lymphoma in developed countries. It accounts for about 7 out of 10 cases. It is most common in teens and young adults, but it can occur in people of any age. It tends to start in lymph nodes in the neck or chest.

- Mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma (MCCHL): This is the second most common type, found in about 4 out 10 cases. Mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma (MCCHL) is seen mostly in people with HIV infection. It’s also found in children or the elderly . It can start in any lymph node but most often occurs in the upper half of the body.

- Lymphocyte-rich Hodgkin lymphoma: Lymphocyte-rich Hodgkin lymphoma isn’t common. It usually occurs in the upper half of the body and is rarely found in more than a few lymph nodes.

- Lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma: This is the least common form of Hodgkin lymphoma. Lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma is seen mainly in older people and those with HIV infection. It’s more aggressive than other types of Hodgkin lymphoma and likely to be advanced when first found. It’s most often in lymph nodes in the abdomen (belly) as well as in the spleen, liver, and bone marrow.

Table 8. Classic Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Subtypes

| Subtype | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Nodular sclerosis Hodgkin lymphoma (NSCHL) | Accounts for 70 percent of classical Hodgkin lymphoma cases Most common type in young adults Involved lymph nodes contain scar tissue (sclerosis) Incidence similar in males and females Highly curable B symptoms in approximately 40 percent of cases |

| Mixed cellularity Hodgkin lymphoma (MCCHL) | Accounts for 20-25 percent of classical Hodgkin lymphoma cases Most common in older adults More common in males Prevalent in patients with HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) infection Involved lymph nodes contain Reed-Sternberg cells and several other cell types B symptoms common |

| Lymphocyte-rich Hodgkin lymphoma | Accounts for approximately 5 percent of classical Hodgkin lymphoma cases Involved lymph nodes contain numerous normal-appearing lymphocytes and Reed-Sternberg cells Usually diagnosed at an early stage More common in males B symptoms are rare |

| Lymphocyte-depleted Hodgkin lymphoma | Rarest classical Hodgkin lymphoma subtype, less than 1 percent of all classical Hodgkin lymphoma cases Involved lymph nodes contain few normal lymphocytes and numerous Reed-Sternberg cells Median age range 30-37 years Prevalent in patients with HIV infection Usually diagnosed at an advance stage B symptoms common |

Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma

Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NLPHL) accounts for about 5% of cases. The cancer cells in nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) are large cells called popcorn cells (because they look like popcorn), which are variants of Reed-Sternberg cells. You may also hear these cells called lymphocytic and histiocytic (L&H) cells.

Nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin lymphoma usually starts in lymph nodes in the neck and under the arm. It can occur in people of any age, and is more common in men than in women. This type of Hodgkin’s lymphoma is treated differently from the classic Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL).

The following are some characteristics of nodular lymphocyte predominant Hodgkin’s lymphoma (NLPHL):

- Most common in 30 to 50 year-old age group

- More common in male than in female patients

- NLPHL is slow growing (indolent) and highly curable.

- Small risk (3-5 percent of cases) of transformation to aggressive non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Hodgkin’s Lymphoma causes

The exact cause of Hodgkin’s lymphoma is unknown. Scientists have found some risk factors that make a person more likely to get Hodgkin disease, but it’s not always clear exactly how these factors might increase risk.

Your risk of developing Hodgkin’s lymphoma is increased if:

- you have a medical condition that weakens your immune system

- you take immunosuppressant medicine

- you’ve previously been exposed to a common virus called the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), which causes infectious mononucleosis or glandular fever. Some researchers think that infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) may sometimes cause DNA changes in B lymphocytes, leading to the development of Reed-Sternberg cells, which are the cancer cells in Hodgkin lymphoma.

You also have an increased risk of developing Hodgkin lymphoma if a first-degree relative (parent, sibling or child) has had the condition, it’s not clear if this is because of an inherited genetic fault or lifestyle factors. However, these cases are uncommon and some experts are studying whether some people have a genetic predisposition to Hodgkin lymphoma.

Hodgkin lymphoma is caused by a change (mutation) in the DNA of a type of white blood cell called B lymphocytes. The exact reason why this happens isn’t known.

DNA is the chemical in your cells that makes up your genes, which control how your cells function. You look like your parents because they are the source of your DNA. But DNA affects more than just how you look.

Some genes control when cells grow, divide into new cells, and die:

- Genes that help cells grow, divide, and stay alive are called oncogenes.

- Genes that slow down cell division or cause cells to die at the right time are called tumor suppressor genes.

Cancers can be caused by DNA changes that turn on oncogenes or turn off tumor suppressor genes.

Scientists have found many gene changes in Reed-Sternberg cells that help the cells grow and divide or live longer than they should. Reed-Sternberg cells also make substances called cytokines, which attract many other cells into the lymph node, enlarging it. In turn, these non-cancerous cells release substances that further help Reed-Sternberg cells grow.

Despite these advances, scientists do not yet know what sets off these processes. An abnormal reaction to infection with Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) or to other infections may be the trigger in some cases. But more research is needed to understand what causes Hodgkin lymphoma.

Hodgkin’s lymphoma Risk Factors

The following risk factors may increase a person’s likelihood of developing Hodgkin lymphoma:

- The Epstein-Bar virus (EBV), known for causing infectious mononucleosis, is associated with the development of Hodgkin lymphoma. The exact role of EBV in the development of Hodgkin lymphoma is not clear. Many people are infected with EBV, but very few develop Hodgkin lymphoma. Parts of the virus are found in Reed-Sternberg cells in about 1 out of 3 people with Hodgkin lymphoma. But most people with Hodgkin lymphoma have no signs of EBV in their cancer cells.

- Having a medical condition that weakens your immune system, such as being infected with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that causes AIDS, have increased probability of developing Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Having medical treatment that weakens your immune system, for example, taking medicine to suppress your immune system after an organ transplant.

- Having previously had non-Hodgkin lymphoma, possibly because of treatment with chemotherapy or radiotherapy

- There are occasional cases of Hodgkin lymphoma in families-having a parent or a sibling with Hodgkin lymphoma may increase the risk of developing the disease. These cases are uncommon, but some experts are studying whether some people have a genetic predisposition to Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Family history: Brothers and sisters of young people with this disease have a higher risk for Hodgkin lymphoma. The risk is very high for an identical twin of a person with Hodgkin lymphoma. But a family link is still uncommon – most people with Hodgkin lymphoma do not have a family history of it. It’s not clear why family history might increase risk. It might be because family members have similar childhood exposures to certain infections (such as Epstein-Barr virus), because they share inherited gene changes that make them more likely to get Hodgkin lymphoma, or some combination of these factors.

- Age: People can be diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma at any age, but it is most common in early adulthood (especially in a person’s 20s) and in late adulthood (after age 55).

- Gender: Hodgkin lyphoma occurs slightly more often in males than in females.

- Being very overweight (obese) – this may be more of a risk factor in women than men

- Smoking

- Geography: Hodgkin lymphoma is most common in the United States, Canada, and Europe, and is least common in African and Asian countries.

- Socioeconomic status: The risk of Hodgkin disease is greater in people with a higher socioeconomic background. The reason for this is not clear. One theory is that children from more affluent families might be exposed to some type of infection (such as Epstein-Barr virus) later in life than children from less affluent families, which might somehow increase their risk.

You can not catch Hodgkin lymphoma from someone else.

Hodgkin’s lymphoma prevention

Few of the known risk factors for Hodgkin lymphoma can be changed, so it’s not possible to prevent most cases of Hodgkin lymphoma at this time.

Infection with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS, is known to increase risk, so one way to limit your risk is to avoid known risk factors for HIV, such as intravenous (IV) drug use or unprotected sex with many partners.

Another risk factor for Hodgkin lymphoma is infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (the cause of infectious mononucleosis, or glandular fever), but there’s no known way to prevent this infection.

Hodgkin’s lymphoma signs and symptoms

The most common early sign of Hodgkin lymphoma is painless swelling (enlargement) of one or more lymph nodes. Most people have affected lymph nodes in the upper part of their body, usually the neck or upper chest. Sometimes the affected lymph nodes are in the armpit, stomach area or groin.

Hodgkin’s lymphoma doesn’t usually hurt, but the area may become painful after drinking alcohol. The lump might grow larger over time, or new lumps might appear near it (or even in other parts of the body).

But Hodgkin lymphoma is not the most common cause of lymph node swelling. Most enlarged lymph nodes, especially in children, are caused by an infection. Lymph nodes that grow because of infection are called reactive or hyperplastic nodes. These often hurt when they are touched. If an infection is the cause, the node should return to its normal size within a few weeks after the infection goes away.

Other cancers can also cause swollen lymph nodes. If you have an enlarged lymph node, especially if you haven’t had a recent infection, it’s best to see your doctor so that the cause can be found and treated without delay, if needed.

In addition to swollen lymph nodes, other signs and symptoms of Hodgkin lymphoma may include:

- Unexplained fever (100.4°F [38ºC] or higher)

- Persistent fatigue

- Persistent cough

- Shortness of breath during normal activity

- Drenching sweats, especially at night

- Unexplained weight loss (weight loss of 10% or more of baseline weight in the previous 6 months)

- Decreased appetite

- Itchy skin (pruritus), especially after bathing or after ingesting alcohol

- Abdominal pain or swelling and feeling of fullness (due to an enlarged spleen)

- Lymph node pain after drinking alcohol

A few people with Hodgkin lymphoma have abnormal cells in their bone marrow when they’re diagnosed. This may lead to:

- persistent tiredness or fatigue

- an increased risk of infections

- excessive bleeding – such as nosebleeds, heavy periods and spots of blood under the skin

Treatment of Hodgkin’s lymphoma should relieve these symptoms within days.

B symptoms

Fever, drenching night sweats and loss of more than 10 percent of body weight over six months are sometimes termed “B symptoms.” These symptoms are significant to the prognosis and staging of the disease.

Some Hodgkin lymphoma symptoms are associated with other, less serious illnesses. However, if you’re troubled by any of the above symptoms, see your doctor.

Hodgkin’s lymphoma diagnosis

Hodgkin lymphoma can be a difficult disease to diagnose because it can be confused with some types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Having the correct diagnosis is important for getting the right treatment. You may want to get a second medical opinion by an experienced hematopathologist before you begin treatment. A hematopathologist is a specialist who studies blood and bone marrow cells and other tissues to help diagnose diseases of the blood, bone marrow and lymph system.

If a person has signs or symptoms that suggest Hodgkin lymphoma, exams and tests will be done to find out for sure and, if so, to determine the exact type.

Medical history and physical exam

Your doctor will want to get a thorough medical history, including information about symptoms, possible risk factors, family history, and other medical conditions.

Next, the doctor will examine you, paying special attention to the lymph nodes and other areas of the body that might be affected, including the spleen and liver. Because infections are the most common cause of enlarged lymph nodes, especially in children, the doctor will look for an infection in the part of the body near any swollen lymph nodes.

The doctor also might order blood tests to look for signs of infection or other problems. If the doctor suspects that Hodgkin lymphoma might be causing the symptoms, he or she might recommend a biopsy of a swollen lymph node.

Lymph Node Biopsy

Diagnosing Hodgkin lymphoma usually involves performing a lymph node biopsy. The entire lymph node or part of the lymph node is surgically removed using a special needle. A hematopathologist examines the sample of the lymph node under a microscope to look for the identifying characteristics of Hodgkin lymphoma. If the biopsy confirms that you have Hodgkin lymphoma, the hematopathologist will categorize the Hodgkin lymphoma into one of several subtypes. .

The lymph node biopsy’s purpose is to confirm a diagnosis and:

- Identify your Hodgkin lymphoma subtype

- Develop a treatment plan

Immunophenotyping

The hematopathologist may use a lab test called immunophenotyping to distinguish Hodgkin lymphoma from other types of lymphoma or other cancerous or noncancerous conditions based on the antigens or markers on the surface of the cells.

Staging Tests

Once your hematologist-oncologist confirms a Hodgkin lymphoma diagnosis, he or she orders more tests to stage your disease. Staging identifies the extent of your disease and where it’s located in your body.

Staging tests include:

- Imaging tests

- Blood tests

- Bone marrow tests

Imaging Tests

Imaging tests help the doctor evaluate:

- The location and distribution of enlarged lymph nodes

- Whether organs other than lymph nodes are involved

- Whether there are very large masses of tumors in one site or another

Imaging tests may include:

- Chest X-ray

- CT (computed tomography) scan of the neck, chest, pelvis and abdomen (stomach area)

- FDG-PET (fluorodeoxyglucose [FDG] positron emission tomography [PET]) of the entire body with a radioactive tracer

- Combination PET-CT scan

- MRI (magnetic resonance imaging)

Blood Tests

Blood tests are used to:

- Assess blood counts including red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets;

- Determine whether lymphoma cells are present in the blood;

- Determine whether the immunoglobulins (proteins that fight infection) made by lymphocytes are deficient or abnormal;

- Check indicators of inflammation and disease severity such as blood protein levels, uric acid levels and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR);

- Assess kidney and liver functions;

- Some women may have a pregnancy test.

Your doctor might also suggest other blood tests to look for signs of certain infections:

- HIV test: This may be done if you have abnormal symptoms that might be related to HIV infection.

- Hepatitis B and C virus test: Certain chemo drugs could cause problems if you have these infections.

Bone Marrow Tests

Your doctor may decide to examine your bone marrow to see whether the disease has spread to the bone marrow. Your doctor will decide if this procedure is necessary based on certain features such as the location of the disease in your body. Bone marrow testing may not be required for patients with early-stage disease and low-risk clinical features.

- Bone marrow testing involves two steps usually done at the same time in a doctor’s office or a hospital:

- A bone marrow aspiration to remove a liquid sample of bone marrow

Tests of heart and lung function

These tests might be done if certain chemo drugs that could affect the heart or the lungs are going to be used.

- An echocardiogram (an ultrasound of the heart) or a MUGA scan can be used to check heart function.

- Lung (pulmonary) function tests (PFTs) can be used to see how well the lungs are working.

Hodgkin Lymphoma Staging

Doctors use physical examinations, imaging tests, blood test and, sometimes, bone marrow tests to determine the extent of the disease. This determination is called “staging.” Staging provides important information for treatment planning.

Staging for Hodgkin lymphoma is based the Lugano classification, which is based on the older Ann Arbor system. It has 4 stages, labeled I, II, III, and IV.

For limited stage (I or II) Hodgkin’s lymphoma that affects an organ outside of the lymph system, the letter E is added to the stage (for example, stage IE or IIE).

- Stage I: The cancer is limited to one lymph node region or a single organ. Either of the following means that the Hodgkin’s lymphoma is stage I:

- Hodgkin’s lymphoma is found in only 1 lymph node area or lymphoid organ such as the thymus (I).

- The cancer is found only in 1 part of 1 organ outside the lymph system (IE).

- Stage II: In this stage, the cancer is in two lymph node regions or the cancer has invaded one organ and the nearby lymph nodes. But the cancer is still limited to a section of the body either above or below the diaphragm. Either of the following means that the Hodgkin’s lymphoma is stage II:

- Hodgkin’s lymphoma is found in 2 or more lymph node areas on the same side of (above or below) the diaphragm, which is the thin muscle beneath the lungs that separates the chest and abdomen (II).

- The cancer extends locally from one lymph node area into a nearby organ (IIE).

- Stage III: When the cancer moves to lymph nodes both above and below the diaphragm, it’s considered stage III. Either of the following means that the Hodgkin’s lymphoma is stage III:

- Hodgkin’s lymphoma is found in lymph node areas on both sides of (above and below) the diaphragm (III).

- Hodgkin’s lymphoma is in lymph nodes above the diaphragm and in the spleen.

- Stage IV: This is the most advanced stage of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Hodgkin’s lymphoma has spread widely into at least one organ outside of the lymph system, such as the liver, bone marrow, or lungs.

Other modifiers may also be used to describe the Hodgkin lymphoma stage:

- Bulky disease. This term is used to describe tumors in the chest that are at least ⅓ as wide as the chest, or tumors in other areas that are at least 10 centimeters (about 4 inches) across. It’s usually labeled by adding the letter X to the stage. It’s especially important for stage II lymphomas, because bulky disease may require more intensive treatment.

- A vs. B. Each stage may also be assigned a letter A or B to indicate whether you’re experiencing symptoms of Hodgkin’s lymphoma:

- The letter A means that you don’t have any significant symptoms as a result of the cancer.

- The Letter B is added (for example stage IIIB) if a person has any of these B symptoms:

- Loss of more than 10% of body weight over the previous 6 months (without dieting)

- Unexplained fever of at least 100.4°F (38°C)

- Drenching night sweats

- If a person has any B symptoms, it usually means the lymphoma is more advanced, and more intensive treatment is often recommended. If no B symptoms are present, the letter A is added to the stage.

- Category E: The patient has Hodgkin lymphoma cells in organs or tissues outside the lymphatic system.

- Category S: The patient has Hodgkin lymphoma cells in the spleen.

Your treatment depends on your stage and category. Patients who fall into the B category usually need more aggressive treatment than A category patients do.

Resistant or recurrent Hodgkin lymphoma

Resistant or recurrent Hodgkin’s lymphoma is not part of the formal staging system, but doctors or nurses might use these terms to describe what’s going on with the lymphoma in some cases.

- The terms resistant or progressive disease are used when the lymphoma does not go away or progresses (grows) while you’re being treated.

- Recurrent or relapsed disease means that Hodgkin’s lymphoma went away with treatment, but it has now come back. If the lymphoma returns, it might be in the same place where it started or in another part of the body. This can happen shortly after treatment or years later.

Table 9. Hodgkin Lymphoma Stages

| Stage I | Involvement of one lymph node group or a group of adjacent nodes |

| Stage II | Involvement of two or more lymph node regions on the same side of the diaphragm (a thin muscle below the lungs) |

| Stage III | Involvement of lymph node groups on both sides of the diaphragm (for example, neck, chest and abdomen) |

| Stage IV | Involvement of lymph nodes on both sides of the diaphragm and/or involvement of one or more organs such as the lungs, spleen, liver, bones or bone marrow |

Figure 6. Hodgkin Lymphoma Stages

[Source 49]Hodgkin’s lymphoma Treatment

Which Hodgkin’s lymphoma treatments are right for you depends on the type and stage of your disease, your overall health, and your preferences. Treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma is changing due to new drugs and research findings from clinical trials. Therefore, before treatment begins, it is important to consider getting a second opinion at a center with a Hodgkin lymphoma expert.

It’s important that your doctor is experienced in treating patients with Hodgkin lymphoma or works in consultation with a Hodgkin lymphoma specialist. This type of specialist is called a hematologist-oncologist.

Hodgkin lymphoma is considered one of the most curable forms of cancer. Hodgkin lymphoma can usually be treated successfully with chemotherapy alone or chemotherapy followed by radiotherapy. Occasionally, chemotherapy may be combined with steroid medicine. Overall, treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma is highly effective and most people with the condition are eventually cured. For many people with Hodgkin lymphoma, starting treatment helps them focus on moving ahead and looking forward to recovery.

More than 80 percent of all patients diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma can be cured by current treatment approaches. The cure rate is higher, approaching 90 percent, in younger patients and in those with early-stage favorable Hodgkin lymphoma. Even in cases of advanced stage Hodgkin lymphoma, the disease is often highly curable.

Most patients become long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Other treatment goals are to:

- Maximize cures in all stages of the disease

- Minimize both short-term and long-term side effects and complications

- Weigh the risks of toxicity against treatment benefits

Types of Hodgkin’s lymphoma treatment

Doctors use several types of approaches and treatment combinations for adults and children with Hodgkin lymphoma, some at different stages:

- Chemotherapy

- Radiotherapy also known as “radiation therapy”

- Monoclonal Antibody Therapy

- Immunotherapy

- Stem cell transplantation also known as bone marrow transplant

- Your doctor may suggest that you participate in a clinical trial. Clinical trials can involve therapy with new drugs and new drug combinations or new approaches to stem cell transplantation.

Pretreatment Considerations

Adults of childbearing age and parents of children diagnosed with Hodgkin lymphoma should ask their doctors for information that may lessen the risk of infertility.

Finding the Best Treatment Approach

The goal of Hodgkin lymphoma treatment is to cure the disease.

- The treatment your doctor recommends is based on several factors, including:

- Your disease subtype

- Your disease stage and category

- Whether your disease is either refractory (the disease does not respond to treatment) or relapsed (the disease has recurred after treatment)

- Your age

- Whether you have coexisting diseases or conditions (for example, heart disease, kidney disease, diabetes)

As you develop a treatment plan with your doctor, be sure to discuss:

- The results you can expect from treatment

- The potential side effects, including long-term effects and late-term effects

- The possibility of participating in a clinical trial, where you may have access to advanced medical treatment that may be more beneficial to you than standard treatment

You may find it helpful to bring a loved one with you to your doctor’s visits for support, to take notes and to ask follow-up questions. It’s a good idea to prepare questions you’d like to ask when you visit your doctor. You can also record your conversations with your doctor and listen more closely when you get home.

Chemotherapy Drug Combinations

Chemotherapy (chemo) is a drug treatment that uses chemicals to kill lymphoma cells. Chemotherapy (chemo) is the main treatment for most people with Hodgkin lymphoma (other than some people with nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma, or NLPHL). Chemotherapy drugs travel through your bloodstream and can reach nearly all areas of your body and destroy cancer cells wherever they may be. Chemotherapy (chemo) can be given in a number of different ways, depending on the stage of your lymphoma. If doctors think your lymphoma is curable, you’ll normally receive chemotherapy through a drip directly into a vein (intravenous chemotherapy). If a cure is unlikely, you may only need to take chemotherapy tablets to help relieve your symptoms.

Chemotherapy is often combined with radiation therapy in people with early-stage classical type Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Radiation therapy is typically done after chemotherapy. In advanced Hodgkin’s lymphoma, chemotherapy may be used alone or combined with radiation therapy.

Children and young adults with Hodgkin lymphoma are usually treated with combination chemotherapy and involved field radiation therapy.

Chemo is given in cycles that include a period of treatment followed by a rest period to give the body time to recover. In general, each cycle lasts for several weeks.

Most chemo treatments are given in the doctor’s office, clinic, or hospital outpatient department, but some may require a hospital stay.

Common chemotherapy drug combinations used to treat children and young adults include:

- ABVD: doxorubicin (Adriamycin®), bleomycin (Blenoxane®), vinblastine (Velban®), dacarbazine (DTIC-Dome®). ABVD is the most common regimen used in the United States.

- AV-PC: doxorubicin (Adriamycin®), vincristine (Oncovin®), prednisone and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan®)

- ABVE: doxorubicin (Adriamycin®), bleomycin (Blenoxane®), vincristine (Oncovin®), and etoposide (Etopophos®, Toposar®, VePesid®, VP-16)

- ABVE-PC: doxorubicin (Adriamycin®), bleomycin (Blenoxane®), vincristine (Oncovin®), etoposide (Etopophos®, Toposar®, VePesid®, VP-16), prednisone and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan®)

- BEACOPP: bleomycin (Blenoxane®), etoposide (Etopophos®, Toposar®, VePesid®, VP-16), doxorubicin (Adriamycin®), cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan®), vincristine (Oncovin®), procarbazine (Matulane®) and prednisone

- OEPA: vincristine (Oncovin®), etoposide (Etopophos®, Toposar®, VePesid®, VP-16), prednisone, and doxorubicin (Adriamycin®)

- Stanford V: Doxorubicin (Adriamycin), Mechlorethamine (nitrogen mustard), Vincristine, Vinblastine, Bleomycin, Etoposide and Prednisone

- Another drug that can be considered as chemo is brentuximab vedotin (Adcetris). This is an antibody-drug conjugate, which is a monoclonal antibody attached to a chemo drug.

Early-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL)

- Chemotherapy combinations

- ABVD (Adriamycin® [doxorubicin], bleomycin, vinblastine, dacarbazine)

- Escalated BEACOPP (bleomycin, etoposide, Adriamycin [doxorubicin], cyclophosphamide, Oncovin® [vincristine], procarbazine, prednisone)

- Combination chemotherapy is administered with or without radiation therapy.

Advanced-stage classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL)

- Chemotherapy combinations

- A+AVD (Adcetris® [brentuximab vedotin], Adriamycin [doxorubicin], vinblastine, dacarbazine)

- ABVD

- ABVD followed by escalated BEACOPP

- Occasionally, chemotherapy is followed by involved-site radiation therapy (ISRT).

Side effects of chemotherapy depend on the drugs you’re given. Common side effects are nausea, vomiting and hair loss. The most significant side effect of chemotherapy is potential damage to your bone marrow. This can interfere with the production of healthy blood cells and cause the following problems:

- fatigue

- breathlessness

- increased vulnerability to infection

- bleeding and bruising more easily

If you experience these problems, treatment may need to be delayed so you can produce more healthy blood cells. Growth factor medicines can also stimulate the production of blood cells.

Other possible side effects of chemotherapy include:

- diarrhea

- loss of appetite

- mouth ulcers

- tiredness

- skin rashes

- infertility, which may be temporary or permanent

Serious long-term complications can occur, such as heart damage, lung damage and other cancers, such as leukemia.

If regular chemotherapy is unsuccessful or Hodgkin lymphoma returns after treatment, you may have a course of chemotherapy at a higher dose.

However, this intensive chemotherapy destroys your bone marrow, leading to the problems mentioned above. You’ll need a stem cell or bone marrow transplant to replace the damaged bone marrow.

Table 10. Chemotherapy Regimens Used to Treat Hodgkin Lymphoma

| Combination Name | Drugs Included | Prognostic Group |

|---|---|---|

| ABVD | Doxorubicin, bleomycin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine | Early favorable classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| Early unfavorable classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma | ||

| AVD | Doxorubicin, vinblastine, and dacarbazine | Early favorable classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| Advanced classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma | ||

| BEACOPP | Bleomycin, etoposide, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone | Early unfavorable classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| Advanced classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma | ||

| GVD | Gemcitabine, vinorelbine, and liposomal doxorubicin | Recurrent classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| ICE | Ifosfamide, carboplatin, and etoposide | Recurrent classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

| MOPP | Mechlorethamine, vincristine, procarbazine, and prednisone | Advanced classic Hodgkin’s lymphoma |

Radiation therapy

Radiation therapy also known as “radiotherapy”, uses high-energy beams, such as X-rays and protons, to kill cancer cells. Radiation therapy is most often used to treat early-stage Hodgkin lymphoma, where the cancer is only in 1 part of the body. Involved-site radiation therapy (ISRT) is sometimes used to treat Hodgkin’s lymphoma. It selectively treats the lymph nodes where the cancer started and the cancerous masses near those nodes. With a special machine, carefully focused beams of radiation are directed at the cancer. This is also called “external beam therapy” (EBT). The size of the targeted area is restricted to minimize radiation exposure to adjacent, uninvolved organs, and to decrease the side effects associated with radiation therapy.