Morphea

Morphea is also known as localized scleroderma, is a rare autoimmune condition that causes painless, discolored patches on your skin 1, 2, 3. Morphea is characterized by an area of inflammation and fibrosis (thickening and hardening) of the skin due to increased collagen deposition. Typically, the morphea skin changes appear on the abdomen, chest or back. But morphea might also appear on your face, arms or legs. Morphea tends to affect only the outermost layers of your skin. But some forms of the condition also restrict movement in the joints.

Several subtypes of morphea exist, each with different clinical manifestations and degree of involvement of the subcutaneous soft tissues 4. Furthermore, morphea may be extremely debilitating. Any subtype of morphea can also result in deep or subdermal involvement of the underlying fat, fascia, muscle or bone. As the skin is adherent to musculoskeletal structures, the thickening of the skin can lead to severe contractures of the extremities, leading to significant loss of function, atrophy, disfigurement, and impairment 5.

The cause of morphea is incompletely understood and is an evolving area of research 1, 6. Studies suggest a multifactorial cause involving dysregulated immune and fibrotic pathways, with additional contributing factors including genetic predisposition, traumatic or environmental factors, and vascular dysregulation 7. The strongest genetic associations with morphea were found with the HLA class II allele DRB1*04:04 and class I allele HLA–B*37 6. The presence of auto-antibodies like antinuclear antibody (ANA), anti-single-stranded DNA (SS DNA), and anti-histone antibodies supports the role of autoimmune dysregulation 6.

Morphea can be distinguished from systemic scleroderma (systemic sclerosis), as morphea lacks a systemic component and spares internal organs 8.

Unlike systemic scleroderma (systemic sclerosis), morphea does NOT cause 9:

- Skin thickening of the fingers and toes (sclerodactyly)

- Specific autoantibodies in the blood (such as anti-centromere antibody or anti-Scl70)

- Abnormal small blood vessels in the fingers (nail fold capillaries)

- Fibrosis and/or vascular damage of internal organs.

Signs and symptoms of morphea vary, depending on the type and stage of the condition. They include:

- Reddish or purplish oval patches of skin, often on the abdomen, chest or back

- Patches that gradually develop a lighter or whitish center

- Linear patches, especially when on the arms or legs

- A gradual change in the affected skin, which becomes hard, thickened, dry and shiny

- Loss of hair and sweat glands in the affected area over time

Morphea usually affects only the skin and underlying tissue and, rarely, bone. The condition generally lasts several years and then disappears on its own. But it usually leaves some patches of darkened or discolored skin.

Morphea is rare, and is estimated to have an incidence of 1–3 per 100,000 children 10, 11, 12. Morphea is three times more common in adult women compared to males (ratio: 2.4–5.0 to 1) and often begins in childhood 13, 14, 15. The peak incidence is bimodal with peaks between 7 and 11 years for pediatric-onset morphea (juvenile localized scleroderma) 15,16, 17 and 44–47 years for adult-onset disease 16, 18. Various antibodies may be found including antinuclear antibodies (ANA), anti-single stranded DNA (anti-ssDNA), anti-histone antibodies (AHA), anti-topoisomerase IIα, anti-phospholipid, and rheumatoid factor 19, 20, 21. Anti-histone antibodies (AHA) were found in 87% of patients with generalized morphea vs. 42% of patients with localized disease. 80% of patients with morphea have a positive antinuclear antibodies (ANA). Although not hereditary, certain HLA subtypes (HLA-DRB1*04:04 and HLA-B*37) are associated with an increased risk of morphea.

The pathological changes of morphea may affect the dermis, subcutis, soft tissue, and sometimes bone. Fibrosis and resultant atrophy of the dermis, soft tissue, and bone can cause significant deformity and functional impairment, such as contractures, limb length discrepancy, or limitations in range of motion 4.

Morphea can follow a protracted course, which can be relapsing and remitting, or chronically active. Milder forms of the disease tend to become inactive within 3–5 years. Very rarely, patients may go on to develop systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma).

The diagnosis of morphea can typically be made based on clinical findings, however biopsy of the lesions and imaging can help confirm the diagnosis or exclude other diagnoses.

Current standard of care therapies for morphea are immunosuppressive agents that aim to shut down disease activity, and thus early and accurate assessment of activity is crucial in preventing permanent cosmetic and functional complications.

Relapse can occur after successful treatment, especially in morphea that begins in childhood.

Extended courses of systemic treatments of 4 to 5 years or more may be required to minimize the risk of relapse.

In the meantime, medications and therapies are available to help treat the skin discoloration and other effects.

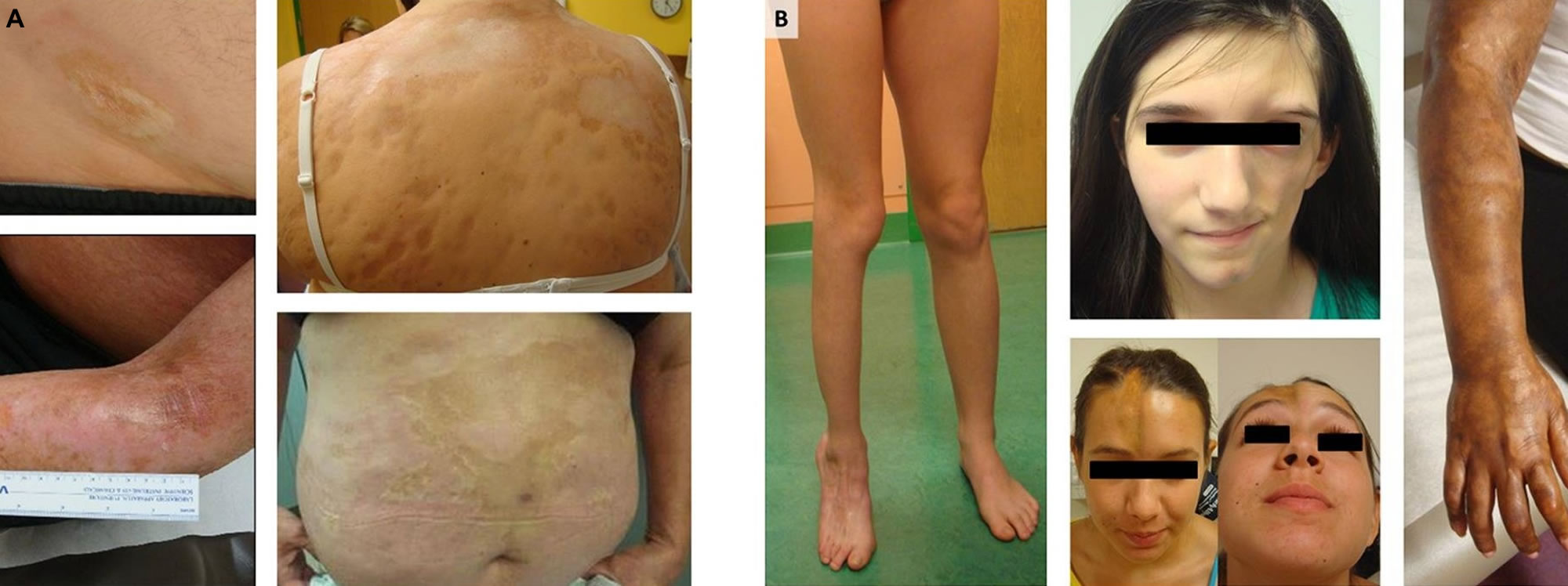

Figure 1. Morphea skin – note the classic violaceous border

Figure 2. Morphea skin disease

Footnote: (A) Generalized morphea and plaque morphea are the most common subtypes of morphea in adult patients, while (B) linear scleroderma of the trunk, limbs, and head are the most common in children.

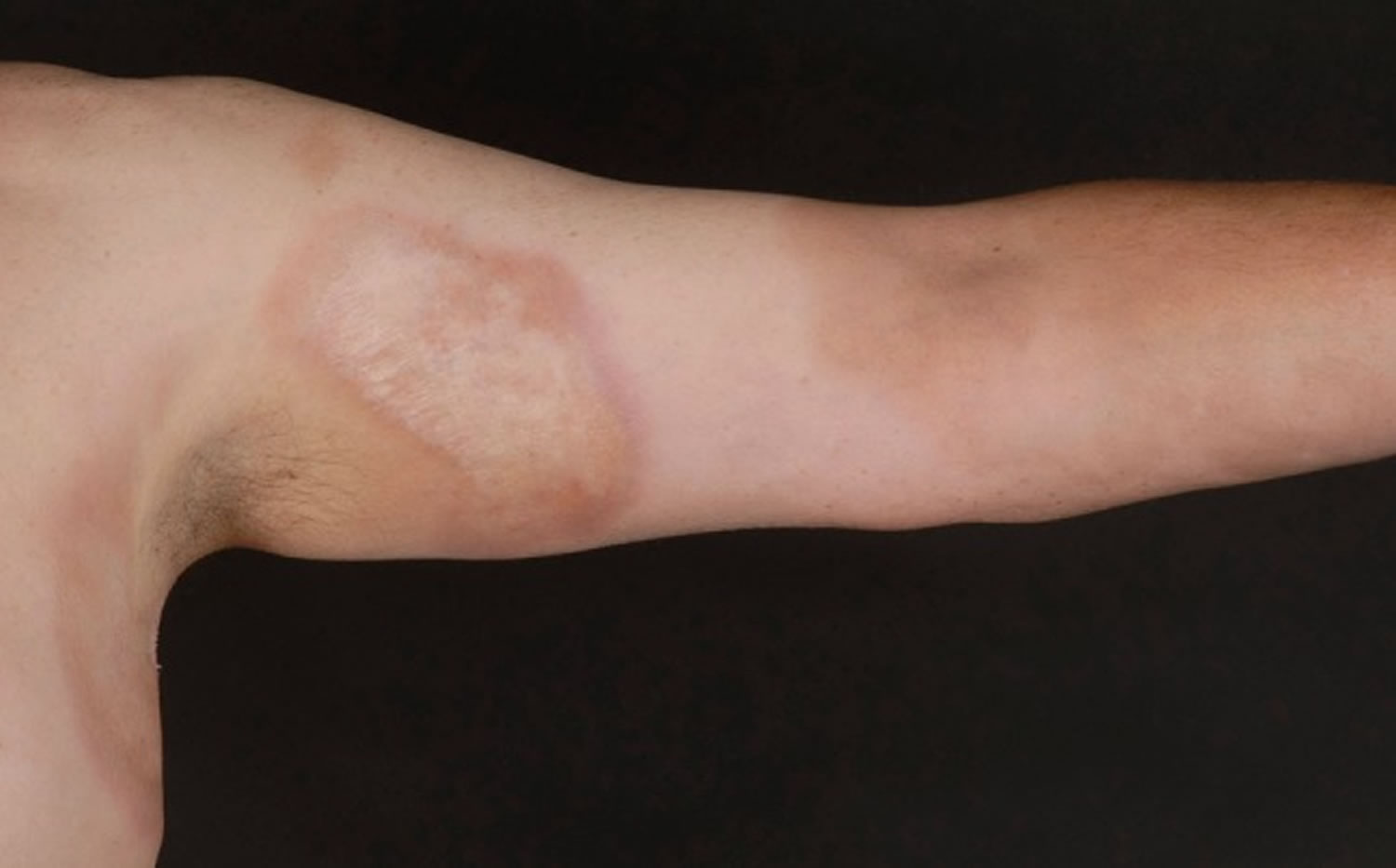

[Source 2 ]Figure 3. Superficial morphea (circumscribed superficial morphea or ‘morphea en plaque’)

Footnote: A yellow-white sclerotic plaque with an erythematous or violaceous border, the characteristic ‘lilac ring’

[Source 3 ]If you notice reddish patches of hardening or thickening skin, see your doctor. Early diagnosis and treatment may help slow the development of new patches and allow your doctor to identify and treat complications before they worsen.

Morphea stages

The specific appearance of morphea varies, and may include:

- An inflammatory phase: pink, purple or bruise-like patches

- Sclerosis: the skin becomes hard, thickened, bound down, shiny, ivory white and may have a purple border of surrounding inflammation. The fibrotic phase often initially overlaps with inflammation and is characterized by dense collagen deposition with admixed inflammatory cells manifesting as hardened yellow to white plaques with an erythematous or violaceous border. These mixed inflammatory and sclerotic lesions ultimately transition into an inactive phase characterized by resolution of inflammation with sclerosis progressing to atrophy of the dermis and sometimes underlying soft tissue.

- Dyspigmention and atrophy. This develops after a variable time period (usually months or years); hyperpigmentation is more common than hypopigmentation. Superficial (dermal) atrophy is seen as shiny skin, often with visible blood vessels. Deeper atrophy affecting fat, muscle or bone presents as concave indentations or discrepancies of limb circumference.

Morphea is defined by periods of activity (inflammation and fibrosis) which leads to damage and atrophy. Activity in morphea is characterized histologically by an inflammatory dermal and subcutaneous lymphocytic infiltrate manifesting clinically as erythema, edema, and lesion extension, with patients reporting symptoms such as pain and pruritis 22. Figure 4 demonstrates typical appearance of both active and inactive lesions.

Early, progressive morphea is characterized by an inflammatory phase – erythematous or violaceous cutaneous lesions. As the disease progresses, sclerotic plaques develop at the center of these lesions. This leads to the appearance of a yellow-white sclerotic plaque with an erythematous or violaceous border, the so-called ‘lilac ring’ (see Figure 3 above). In some patients, development of hyperpigmentation is the predominant feature and sclerosis can be limited or absent (see Figure 9 below).

In the majority of patients, skin softens in months to years. Consecutively, signs of residual damage, such as pigment alterations and cutaneous and subcutaneous atrophy, may develop. Whilst morphea classically passes through each of these morphological stages, this is not always the case. In most patients, morphea is self-limiting within 3–5 years. However, in some patients morphea remains progressive for multiple years or flares of disease occur frequently 3.

Figure 4. Morphea stages

Footnote: Morphea is characterized by periods of activity (A,C) and damage (B,D). (A) Right arm affected with significant inflammation, evidenced in swelling of digits and forearm. (B) Damage from morphea including joint contractures and hyperpigmented sclerotic plaques. (C) Active, inflammatory plaque on abdomen with striae. (D) Morphea damage with hyperpigmented, sclerotic plaques, atrophy.

[Source 1 ]Types of morphea

Multiple classification schemes have been proposed throughout the years. However, consensus with regard to one superior classification system is currently lacking 3. Classification by Laxer and Zulian 23, also known as the Padua criteria, describes the following five subtypes:

- Circumscribed morphea (including a superficial and deep variant),

- Linear morphea (including a limb/trunk variant and head variant),

- Generalized morphea,

- Pansclerotic subtype,

- Mixed subtype.

Other classification systems include more uncommon subtypes such as guttate and bullous morphea 24. In 2017, the European Dermatology Forum proposed a classification system with five subtypes which includes: plaque, guttate, and superficial morphea, generalized morphea which includes generalized and pansclerotic subtypes, linear, deep, and mixed 25.

Of all the different classification schemes, the Laxer and Zulian’s Padua criteria likely performs the best at successfully capturing the most relevant disease subsets in morphea 1. In a recent large prospective cohort study of adult and pediatric-onset morphea patients, the Padua criteria correctly categorized 95% of patients (900/944), in comparison to other classification schemes which only correctly categorized 51–54% of patients 26. Furthermore, the groups created using the Padua criteria were found to have cohesive clinical and demographic features. However, there remain some ambiguities in the Padua criteria, such as how patients with multiple linear lesions who also meet criteria for generalized disease should be categorized, when patients with multiple linear lesions have been shown to be a distinct group with consistent demographic and clinical characteristics 27. Additionally, findings like deep involvement occur across linear, generalized, and circumscribed lesions and may be better considered a descriptor and not a separate subtype.

When describing morphea, consider three features.

- Anatomical distribution: location and whether limited, linear, generalized or mixed

- Morphology: inflammatory, sclerotic, dypsigmented and/or atrophic

- Depth of tissue involvement: skin, fat, fascia, muscle, bone

Anatomical distribution

- Subtypes of morphea are limited, linear, generalized or mixed.

Limited plaque morphea

- The most common type in adults

- Oval shaped patches of 1 to 20cm in diameter

- Two or fewer body sites.

Rare types of limited plaque morphea include guttate morphea and atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini.

Table 1. Classification of morphea subtypes

| Main group | Subtype | Description |

|---|---|---|

| (1) Circumscribed morphea | Superficial | Oval or round circumscribed areas of induration limited to epidermis and dermis, often with altered pigmentation and violaceous, erythematous halo (‘lilac ring’). They can be single or multiple |

| Deep | Oval or round circumscribed deep induration of the skin involving subcutaneous tissue extending to fascia and may involve underlying muscle. The lesions can be single or multiple. Sometimes the primary site of involvement is in the subcutaneous tissue without involvement of the skin | |

| (2) Linear morphea | Trunk/limbs | Linear induration involving dermis, subcutaneous tissue, and sometimes muscle and underlying bone, and affecting the limbs and the trunk |

| Head | En coup de sabre (ECDS): Linear induration that affects the face and the scalp and sometimes involves muscle and underlying bone Parry–Romberg or progressive hemifacial atrophy: loss of tissue on one side of the face that may involve dermis, subcutaneous tissue, muscle and bone. The skin is mobile | |

| (3) Generalized morphea | Induration of the skin starting as individual plaques (four or more and larger than 3 cm) that become confluent and involve at least two out of seven anatomic sites (head/neck, right upper extremity, left upper extremity, right lower extremity, left lower extremity, anterior trunk, posterior trunk) | |

| (4) Pansclerotic morphea | Circumferential involvement of limb(s) affecting the skin, subcutaneous tissue, muscle and bone. The lesion may also involve other areas of the body without internal organ involvement | |

| (5) Mixed morphea | Combination of two or more of the previous subtypes. The order of the concomitant subtypes, specified in brackets, will follow their predominant representation in the individual patient [i.e., mixed morphea (linear-circumscribed)] | |

Scleroderma Variants

| Disease | Features |

|---|---|

| Morphea (Localized) | Indurated, sclerotic plaques, usually on the trunk. |

| Generalized Morphea | Two or more body regions involved. May have muscle atrophy, but no systemic involvement. Induration of the skin starting as individual plaques (four or more and larger than 3 cm) that become confluent and involve at least two out of seven anatomic sites (head/neck, right upper extremity, left upper extremity, right lower extremity, left lower extremity, anterior trunk, posterior trunk) |

| Superficial morphea | Multiple hypopigmented to hyperpigmented patches and plaques. They usually involve intertriginous sites symmetrically and lack significant induration, contractures, or atrophy. |

| Progressive Systemic Sclerosis | Raynaud’s, woody edema of hands, sclerodactyly, internal organ involvement, e.g., pulmonary fibrosis. |

| CREST Syndrome | Calcinosis, Raynaud’s, esophageal dysmotility, sclerodactyly, and telangiectasias. |

| Linear Scleroderma | Linear indurated lesions. May follow lines of Blaschko. |

| Morphea Profunda | Process involves the deep subcutaneous tissue including the fascia. |

| Pansclerotic Morphea | Widespread involvement of the deeper tissue including the fat fascia, muscle, and bone. |

| Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini (APP) | Brown, atrophic depressed lesions, usually on the trunk of women. |

| Linear Atrophoderma of Moulin | Similar to Atrophoderma of Pasini and Pierini but linear and may follow lines of Blaschko. |

| En Coup de Sabre | Linear atrophic, indurated lesion running along scalp and forehead. |

| Parry Romberg | Atrophy of one side of the facial skin with possible involvement of the muscle, fat, cartilage, bone, and brain. |

Linear morphea (Linear scleroderma)

Linear morphea (linear scleroderma) is a form of localized scleroderma characterized by sclerotic lesions distributed in a linear, band-like pattern. Linear morphea (linear scleroderma) is more common in children but occurs in adults as well.

A ‘band-like’ linear induration (sclerosis), often with hypo or hyperpigmented areas, linear morphea most commonly seen on the leg but also arm and forehead (en coup de sabre) is characteristic. A deep component with fixation to underlying structures may be present. Joint pain is quite common and joint contractures due to skin and tissue involvement may occur 28. In the majority of patients, the disease remains unilateral. Additionally, limb-length discrepancies may occur 15. Linear morphea is the most common subtype in childhood-onset morphea (~65%) 13, but disease onset might occur during adulthood as well 28, 16. Twenty percent of patients have onset by age 10; 75% by age 40. An underlying sclerosing bone dysplasia called melorheostosis can occur with the X-ray appearance said to resemble dripping candle wax. ANA (antinuclear antibodies) may be strongly positive but often the diagnosis is made clinically.

- Most common subtype in children

- Found on the limbs, trunk or head (craniofacial)

- Follows lines and swirls called Blaschko lines

- Usually unilateral, but may be bilateral and widespread in severe cases.

Linear atrophoderma of moulin is a rare subtype of atrophic and pigmented linear morphea.

Linear morphea of the limbs and trunk is characterized by a chronic disease course, as the disease may remain active after many decades 29 and recurrences are reported in a large proportion of both adults and children 28, 30, 31, 16, 32.

Craniofacial linear morphea was previously sub-classified as:

- En coup de sabre (linear atrophic band +/- sclerosis, classically on the forehead or scalp)

- Parry Romberg syndrome / progressive hemifacial atrophy (atrophy of the fat, muscle and bone +/- dyspigmented +/- sclerotic changes, affecting one side of the face).

These types of craniofacial linear morphea occur together, and vary based on morphology and depth of tissue involvement.

The ‘en coup de sabre’ linear morphea subtype most frequently affects the paramedian forehead (Figure 5). Linear lesions may extent onto the scalp, where they cause alopecia (Figure 5). The ‘en coup de sabre’ linear morphea subtype might be accompanied by ocular involvement 33, neurological complications 34 and odontostomatologic complications 35, 36. Progressive hemifacial atrophy (Parry–Romberg syndrome) is characterized by diffuse unilateral subcutaneous atrophy of the face. This subtype is often regarded part of a spectrum with ‘en coup de sabre’ linear morphea subtype because 71% of the patients have overlaying cutaneous sclerosis 37, 34. However, studies that investigate the connection between these two conditions are lacking.

Figure 5. Linear morphea

Figure 6. Linear morphea scalp (en coup de sabre) causing alopecia

Footnote: A 14‐year‐old boy with linear scleroderma en coup de sabre. Skin hyperpigmentation and atrophy of the forehead extended toward the scalp and the inner part of the eye socket; with loss of the inner third of the upper eyelashes and eyebrow of the left eye.

[Source 33 ]Figure 7. Morphea skin in children

Figure 8. Morphea scleroderma with central lichen sclerosus on the anterior thigh of a young girl

Generalized morphea

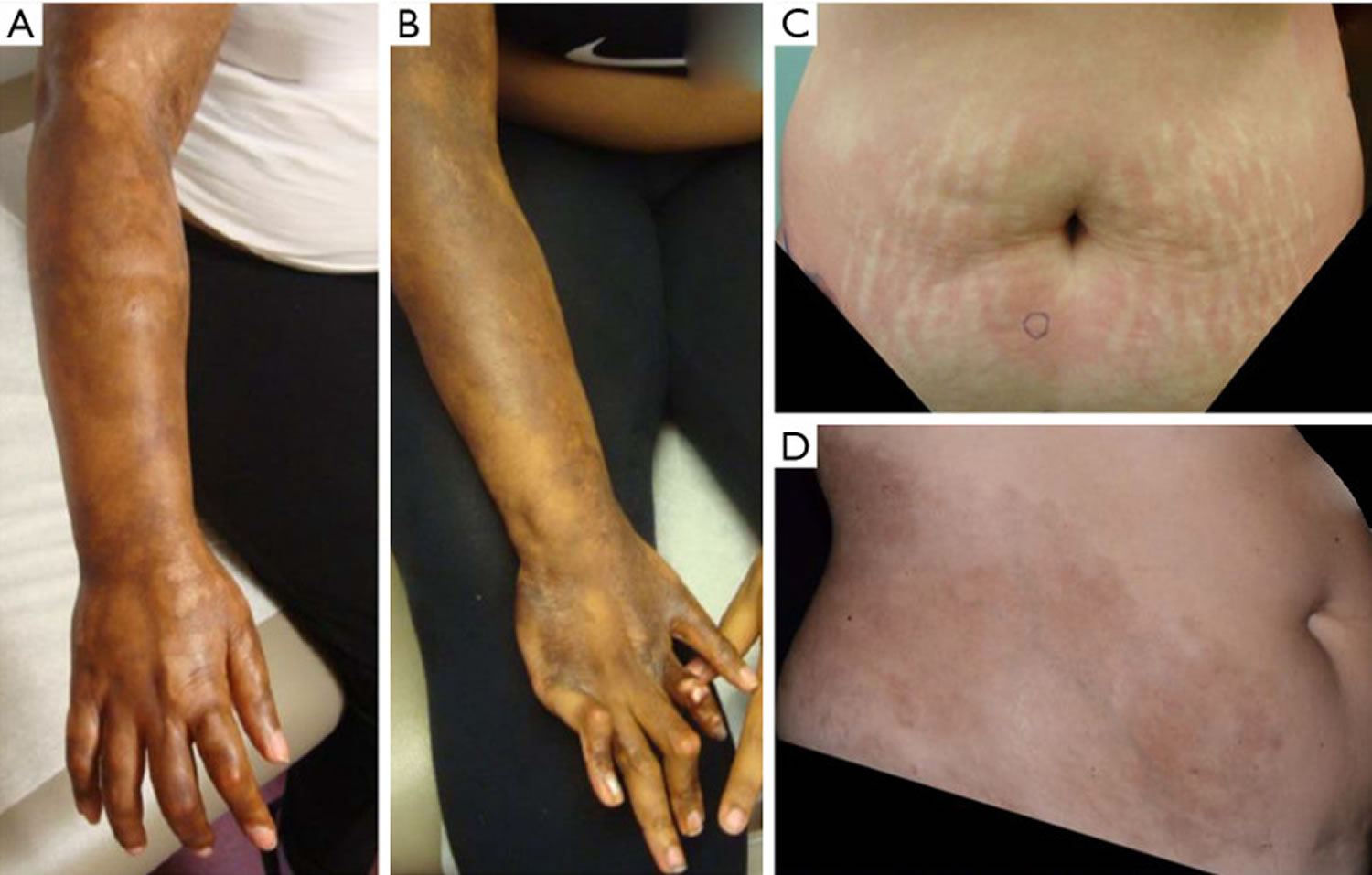

Generalized morphea affects three or more body sites. Generalized morphea is characterized by large superficial coalesced plaques on multiple body sites (Figure 9). Sclerosis is usually present on the trunk, arms, and legs with sparing of the face, hands, and feet. There are two major patterns;

- Disseminated plaque morphea: scattered plaques with intervening unaffected skin. May be isomorphic (occurring at sites of friction such as the waistband, bra line and inguinal creases) or non-isomorphic (scattered plaques at any site).

- Pansclerotic morhpea: circumferential, confluent sclerosis, which is usually rapidly progressive and affects most of the body surface area. This occurs in childhood (disabling pansclerotic morphea of childhood), and adulthood (when it overlaps with eosinophilic fasciitis).

- Generalized morphea spares the digits and periareolar skin.

Generalized morphea is more frequently present in adults than children 14, 16.

Figure 9. Generalized morphea

Footnote: Generalized morphea example with absence of induration, but extensive hyperpigmentation

[Source 3 ]Circumscribed superficial morphea

Circumscribed superficial morphea also known as ‘morphea en plaque’, involvement is limited to the dermis 14, 16. Solitary or few plaques predominantly affect the trunk, waist and submammary region. Circumscribed superficial morphea is the most common subtype in adults and generally causes few problems besides local discomfort and visible disfigurement.

Deep morphea

Deep morphea also known as morphea profunda, sclerosis reaching into the subcutis is present and may extend into the fascia and muscle 3. Deep morphea is a rare subtype in both the adult and pediatric populations (~5%) 15, 14, 16. Lower extremities are often affected symmetrically, where sclerosis might cause contractures and lead to subcutaneous atrophy.

Mixed pattern morphea

- Mixed pattern morphea occurs when more than one anatomical subtype is present.

- The most common mixed pattern is linear morphea of a limb, with limited plaque morphea on the trunk.

Limited morphea is considered mild, while linear morphea and generalised morphea are more severe subtypes. The depth of tissue involvement is also important when assessing disease severity; subdermal involvement implies more severe disease.

Deep tissue involvement in morphea

Any subtype of morphea can affect connective tissue under the skin, such as the fat, fascia, muscle, bone, joints or rarely, brain (in craniofacial linear morphea). Deep tissue involvement is a marker of severe disease.

When the fascia — the connective tissue under the fat — is involved:

- The skin can look puckered, with a cobblestone or orange peel appearance (peau d’orange)

- There may be guttering along blood vessels (the groove sign).

Involvement of bones or joints results in loss of bony tissue, pain and/or restricted joint movement (contractures).

Eosinophilic fasciitis is a form of pansclerotic morphea with deep fascial involvement. Circumferential inflammation and sclerosis of the fascia (the connective tissue beneath the fat) frequently co-exists with overlying dermal sclerosis or other anatomical subtypes of morphea indicating it is debatable whether it should be considered a separate condition.

Morphea causes

The cause of morphea is unknown. It may be due in part to an unusual reaction of the immune system. A variety of factors are involved in the occurrence of morphea. These include autoimmunity, genetic predisposition (HLA class 1 and 2 alleles), and environmental triggers (infections, trauma, toxins, drugs and radiation) 38. The fibrosis (thickening or scarring of the tissue) which occurs is secondary to a series of events that occurs in the skin, starting with an influx of mononuclear cells which infiltrate the dermis and surround the blood vessels. This is followed by vascular injury resulting in functional and structural changes in the vessels, especially the vessels underlying the epidermis. There is also upregulation of adhesion molecules like intercellular adhesion molecule1 and vascular cell adhesion molecule in response to cytokines such as interferon gamma (IFN-γ), interleukin-1 (IL-1) and tumor necrosis factors (TNFs) 38. Interleukin-4 (IL-4) produced by the CD4+ Th2 lymphocytes upregulates the production of transforming growth factor-beta (TGF-β). The fibrosis is induced by excessive TGF-β and IL-4 activity 39, 40.

- Localized genetic factors appear to play a role; for example, cutaneous mosaicism may important in linear morphea, which follows Blaschko lines of epidermal development.

- Up to 40% of patients with severe forms of morphea have a personal or family history of autoimmune disease (e.g, thyroid disease, vitiligo) or rheumatologic disease (eg, rheumatoid arthritis).

For unknown reasons, morphoea often develops after an external trigger such as:

- Radiation therapy (radiotherapy)

- Repeated trauma to the affected area. Trauma-related morphea may occur at the affected site, or at unrelated distant sites.

- A recent infection, such as measles or chickenpox

- Insect bite or tick bite (the role of Borellia burgdorferi, cause of Lyme disease is controversial)

- Injection (e.g., bleomycin, silicone) or vaccination

- Repeated minor friction along the waistband, bra strap and inguinal region, in isomorphic disseminated plaque morphoea.

- Surgery

- Penetrating wound

- Extreme exercise

Morphea isn’t contagious. Trauma-related morphoea may occur at the affected site, or at unrelated distant sites.

Risk factors for developing morphea

Certain factors may affect your risk of developing morphea, including:

- Your sex and age. Females are more likely to develop morphea than are males. The condition can affect people at any age. It usually appears between the ages of 2 and 14 or in the mid-40s.

- Your race. Morphea is more prevalent among Caucasians.

- A family history of morphea. This condition can run in families. People with morphea are more likely to have a family history of morphea and other autoimmune diseases.

Morphea complications

Morphea can cause a number of complications, including:

- Self-esteem issues. Morphea can have a negative effect on your self-esteem and body image, particularly if discolored patches of skin appear on your arms, legs or face. Because morphea affects your appearance, it can be an especially difficult condition to live with. You may also be concerned that it will get worse before it goes away.

- Movement problems. Morphea that affects the arms or legs can impair joint mobility.

- Widespread areas of hardened, discolored skin. Numerous new patches of hard, discolored skin may seem to join together, a condition known as generalized morphea.

- Eye damage. Children with head and neck morphea may experience unnoticeable, permanent eye damage.

Morphea symptoms

Morphea signs and symptoms depend on the type of morphea 5. Morphoea may be asymptomatic, or symptoms may arise from the skin or deeper tissues, or they may due to extracutaneous manifestations.

Morphea skin disease symptoms

- Some patients experience itch and/or pain from actively inflamed areas of morphea.

- Adnexal structures are destroyed by sclerosis. This is of particular relevance in linear morphea of the scalp, which results in permanent hair loss.

- The sclerosis can entrap superficial nerves and result in pain, tingling and sometimes mild weakness.

Morphea profunda symptoms

- Deep involvement over joints causes joint pain or limited joint movement (contractures).

- Constriction of the chest wall in generalized pansclerotic morphea can result in shortness of breath.

- Teeth and jaw involvement in craniofacial linear morphea can cause oral and dental problems. Temporomandibular joint involvement causes difficulty chewing, jaw locking or pain.

- Skull and/or brain involvement can cause headaches or in some rare cases, neurological symptoms such as nerve palsies or seizures.

Neurologic involvement in morphea can take the form of various manifestations such as migraines, seizures, focal neurologic deficits, and movement disorders 41. Literature regarding neurologic findings in morphea is also primarily in the form of case reports and case series 42, 41. Some reviews and reports suggest a role for neuroimaging in these patients, as MRI and CT which can demonstrate findings such as subcortical calcifications and brain atrophy associated with cutaneous lesions of morphea involving the head 43. However, the significance of these findings is uncertain as some patients present with severe symptoms and deficits with no changes on imaging, and some patients with imaging findings do not have significant neuroimaging findings 44. Additionally, there is uncertainly regarding whether these lesions respond to immunosuppressive agents or are better treated by directly targeting neurological symptoms, particularly in the absence of any sign of central nervous system (CNS) inflammation on evaluation. Thus, there remains a need for further study in this area.

Patients with localizing neurologic clinical manifestations such as hemiplegia or visual field deficits would benefit from prompt multidisciplinary evaluation with consideration of neuroimaging to rule out emergencies such as central nervous system (CNS) or optic vasculitis 4. Current literature suggests that the severity of cutaneous morphea may not correlate with severity of nervous system involvement, i.e., there are cases of patients with subtle skin findings but striking MRI findings and severe neurologic manifestations 44, 45.

Musculoskeletal manifestations of morphea can arise when the disease affects not only the skin but also underlying structures such as fascia, muscle, and even joints and bone 46. When this occurs, morphea can be associated with severe pain, flexion contractures, and functional impairment due to decreased range of motion 47. Deep morphea lesions often have very subtle surface changes, and palpation can be more important than visual inspection to appreciate the extent of these lesions. It also may be difficult to fully evaluate activity in these deeper lesions, and given that unchecked morphea activity can lead to permanent functional sequelae, patients with these deeper manifestations of morphea may benefit from MRI to determine disease activity and damage 48. Although involvement of joints and areas underlying areas of morphea is the most common presentation, patients may also experience sacroiliitis, generalized synovitis, and inflammatory arthritis. Although musculoskeletal involvement has been more extensively reported in children with linear morphea, limitation of range of motion has also been reported in adults with generalized symmetric morphea. Little is known however about the association with findings like arthritis and the activity of the cutaneous lesions or their optimal treatment, while soft tissue involvement appears to be associated with deep cutaneous lesions and is linked with activity of the cutaneous disease 49. Thus it is important for patients with morphea, particularly with linear subtype or deep cutaneous involvement, to undergo a thorough examination of the musculoskeletal system and prompt evaluation by rheumatology, orthopedics, or physical medicine and rehabilitation as needed 4.

Morphea systemic symptoms

Newer studies show that morphea is associated with extracutaneous manifestations, these include mucocutaneous, neurological, musculoskeletal, and ophthalmologic involvement 4. Up to 30% of patients with more severe types of linear or generalized morphea can have extracutaneous non-specific inflammatory symptoms. These include:

- Fatigue, lethargy

- Non-specific joint pain and/or inflammation (arthralgia, arthritis)

- Muscle pain

- Reflux/heartburn

- Raynaud phenomenon (cold hands with red/white/blue colour changes)

- Eye dryness, irritation or blurred vision due to ocular involvement (most commonly episcleritis, anterior uveitis, keratitis) – related or unrelated to the site of morphea

These extracutaneous manifestations imply that morphea is a systemic inflammatory condition. In contrast, systemic sclerosis results in direct damage and fibrosis of the lungs, heart, kidneys and/or gastrointestinal tract — which do not occur in morphea.

Mucocutaneous findings in morphea are seen in the form of genital and oral lesions. Genital lesions in morphea occur predominantly in post-menopausal women, and are associated with more superficial dermal morphea and accompanying extragenital lichen sclerosus lesions 50. Studies have shown that genital lichen sclerosus et atrophicus and morphea lesions in extragenital sites may co-exist, thus supporting examination of genitalia in those with morphea and the extra genital skin in those with lichen sclerosus et atrophicus, particularly in post menopausal women 51. Oral involvement has been reported mainly through case reports and case series in the context of facial linear morphea lesions, and can include abnormalities of dentition, loss of oral structures, functional impairments from sclerosis of tissue (i.e., decreased oral aperture), as well as arthritis and mechanical dysfunction with temporomandibular joint pain 52, 53, 54. Oral lesions tend to directly underlie the cutaneous and soft tissue morphea lesions, and often show abrupt demarcation at the midline similar to cutaneous lesions 55. In general, there is a lack of large, systematic studies on the frequency and type of oral and genital involvement across morphea subtypes, and further work is required in order to better characterize mucocutaneous findings in morphea 51.

Ophthalmologic involvement of morphea is rare, and is generally associated with linear morphea involving the head. Literature regarding this is primarily in the form of case reports and a large international case series, which describe features such as diplopia related to involvement of periocular muscles and/or inflammatory changes such as uveitis and episcleritis 33. Central nervous system (CNS) involvement leading to ophthalmologic change has also been reported 56. Patients reporting visual changes or even patients with morphea lesions in close proximity to the periorbital region should be promptly referred to an ophthalmologist for evaluation 4.

Morphea differential diagnosis

Differentiation between morphea and systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma) is commonly requested in an outpatient clinic. It is vital to differentiate morphea (localized scleroderma) from systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma) due to its systemic organ involvement and bad prognosis with delay in diagnosis. In the vast majority of patients, differentiation between the two diseases should be based on clinical findings and no additional testing is necessary in the absence of systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma) suspicion. Patients should be evaluated for the presence of Raynaud’s phenomenon, sclerodactyly, calcinosis cutis, and telangiectasia, which warrants further testing for systemic sclerosis with serologies, capillaroscopy, and pulmonary testing.

Raynaud’s phenomenon or gastrointestinal problems are early signs of systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma) and should therefore be checked in the patients’ history. Signs of systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma) such as sclerodactyly, digital ulcers, pitting scars, puffy fingers, calcinosis cutis, telangiectasia, and diffuse facial sclerosis are rarely present in morphea and should be excluded by clinical examination.

Two studies investigated differentiating characteristics between morphea and systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma) skin biopsies. These studies identified abundant cellular infiltrates in morphea compared with systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma), even in the sclerotic phase of morphea. However, most signs overlapped and differentiation remained difficult 57, 58. Therefore, experts do not recommend routine skin biopsies for the purpose of differentiation between morphea and systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma).

If systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma) suspicion is present at any of the aforementioned steps, complete screening for systemic sclerosis (systemic scleroderma), including extensive laboratory testing, pulmonary imaging and functional testing, cardiac imaging, and nailfold capillaroscopy, is recommended 59.

It is also important to differentiate morphea from other fibrotic skin conditions like scleromyxedema, lipodermatosclerosis, and post-irradiation morphea. Sclermyxedema is seen in patients with systemic diseases like plasma cell dyscrasias. Skin biopsy shows a diffuse deposit of mucin composed primarily of hyaluronic acid in the upper and mid reticular dermis.

Radiation-induced morphea is a rare and chronically progressive localized scleroderma after radiation.

Morphea diagnosis

Your doctor may diagnosis morphea by examining the affected skin and asking you about your signs and symptoms. He or she may take a small sample of the affected skin (skin biopsy) for examination in the laboratory. This may reveal changes in your skin, such as thickening of the collagen in the second layer of skin (dermis). Collagen is a protein that makes up your connective tissues, including your skin. It helps make your skin elastic and resilient.

It’s important to distinguish morphea from systemic scleroderma, so if you have morphea, your doctor will likely refer you to a specialist in skin disorders (dermatologist) or diseases of the joints, bones and muscles (rheumatologist).

If your child has head and neck morphea, take him or her in for regular comprehensive eye exams, as morphea may cause unnoticeable yet irreversible eye damage.

Ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be useful in monitoring disease progression and how it is responding to treatment.

Skin biopsy

A skin biopsy enables the skin, subcutaneous fat (and sometimes fascia) to be examined under the microscope. Classic findings in morphea include:

- Sharply squared-off biopsy (‘cookie cutter’ sign)

- Atrophic epidermis

- Thickened, hyalinised collagen, with possible loss of appendageal structures (such as sweat glands and hair follicles)

- Fat loss / entrapment

- Inflammatory cell infiltrate (lymphocytes +/- plasma cells).

Blood tests

- Eosinophil count (may be raised)

- Inflammatory markers (ESR or CRP may be raised)

- Anti-nuclear antibody (may be raised; but systemic sclerosis specific ENA antibodies such as anti-Sc70 are negative)

- Thyroid function tests (may be abnormal; consider if at risk of associated autoimmune thyroid disease)

- Rheumatoid factor or anti-CCP antibodies if arthralgia/arthritis (may be raised)

Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may be performed to assess how deep the morphea extends beyond the skin, for example in generalized morphea, linear morphea crossing joints, and craniofacial linear morphea.

Morphea treatment

Morphea usually goes away without treatment, though it may leave scars or areas of discolored skin. Until your condition clears up, you may want to pursue treatment that helps control your signs and symptoms.

There is no cure for morphoea. Treatment of morphea depends on clinical activity, depth of lesion involvement, and extent of disease, and primarily centers around limiting disease activity 4. Treatment is aimed at halting ongoing disease activity and progression.

Treatment options include:

- Light therapy. A special treatment that uses ultraviolet light (phototherapy) may improve your skin’s appearance, especially when used soon after skin changes appear.

- Drugs that fight inflammation. For severe or widespread morphea, your doctor may prescribe an immunosuppressive medication, such as oral methotrexate (Rheumatrex, Trexall). This may be used in combination with corticosteroid pills for the first few months. Or your doctor may suggest hydroxychloroquine (Plaquenil) or mycophenolate mofetil. Each of these drugs has potentially serious side effects. Talk with your doctor about a drug’s risks and benefits before using it.

- A form of vitamin D. The prescription cream calcipotriene is a synthetic form of vitamin D. It may help soften the skin patches caused by morphea. Skin generally begins to improve during the first months of treatment. Possible side effects include burning, stinging and a rash.

- Medicated creams. Your doctor may prescribe a corticosteroid cream to reduce inflammation. When used for a long time, these creams may thin the skin.

- Physical therapy. This type of treatment uses exercise to prevent joint deformity and maintain movement.

Active lesions that are isolated to a limited surface area can be treated by topical or intralesional steroids, as well as calcineurin inhibitors such as tacrolimus 1. Topical corticosteroids are first-line treatment for superficial morphea, and the usual treatment is for 3-4 weeks. Topical tacrolimus 0.1% is an alternate choice for superficial circumscribed morphea 60. A 3-month open-label study with topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment twice daily under occlusion demonstrated complete resolution of early lesions and softening of late sclerotic lesions 61. Another open-label study reported improvement in 9 out of 13 patients with topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment, twice daily without occlusion 62. Some experts recommend topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment, either with or without occlusion, twice daily as an alternative or additional topical therapy for superficial morphea. Additionally, based on a recent case report, experts do not recommend topical tacrolimus in radiation-induced morphea 63.

For patients with more generalized dermal involvement or rapidly developing new lesions and deep morphea, ultraviolet (UV) phototherapy can also be used. Lower wavelength phototherapy ultraviolet A1 (UVA1) (wavelength of 340–400 mm) has greater tissue penetration than ultraviolet B (UVB) and has a low risk of sunburn 64. If ultraviolet A1 (UVA1) (wavelength of 340–400 mm) is not available, other options for phototherapy include broadband UVA (320–400 mm), narrowband UVB (nbUVB) and PUVA (psoralen and long-wave ultraviolet A) 65. Phototherapy is ineffective for morphea involving the subcutaneous tissue, muscle, or bone. Patients who do not have access to UVA therapy can be treated with high potency topical corticosteroids, intralesional corticosteroids, or topical tacrolimus.

Other procedures that have been reported to be effective in the treatment of some morphea patients include photodynamic therapy and pulsed dye laser therapy for sclerotic lesions, intralesional hyaluronidase injections for morphea-induced microstomia, and extracorporeal photochemotherapy for severe, generalized disease 54, 64, 66. Further research into these agents and procedures is warranted in order to more clearly define efficacy and indications for use before they should be used as first line agents.

Systemic therapy in morphea is indicated for those with moderate-severe disease, large body surface area involvement, deep involvement, or for lesions that may impact function/cosmesis (facial lesions). There are a wide variety of systemic therapies other than methotrexate, systemic glucocorticoids, and mycophenolate used for active morphea. The most widely investigated systemic therapies include combinations of methotrexate and corticosteroids. Mycophenolate mofetil is an emerging alternative to methotrexate for those who cannot tolerate or have contraindications to methotrexate 67. These medications maybe limited by lack of tolerance or toxicity in many patients, underscoring the need for less toxic therapy 68, 69, 70. Other systemic therapies used for morphea include bosentan, infliximab, tofacitinib, and abatacept 1. While these treatments show promise, current data is insufficient to confirm efficacy of routine use, and further study is necessary.

Damage that results after active lesions progress to an inactive state include atrophy, pigment changes and functional impairment. Damage tends to remain stable or increase after successful management of active disease 71. Once lesions are clinically inactive, treatment centers around improving quality of life by addressing cosmetic and functional concerns. Sclerosis and atrophy due to morphea can lead to limb-length discrepancies, contractures, and limited range of motion. It is important to refer these patients to physical therapy, occupational therapy or specialties such as rheumatology or orthopedics early in order to reduce disability. In addition to functional impairment patients also suffer from cosmetic damage. Dermal fillers and surgical procedures, such as fat transfer, can help restore contour to lesions with significant atrophy. Recent studies have shown the utility of adipose tissue as filler for its ability to regenerate soft tissues and remodeling capacity provided by its unique cytokine and growth factor profiles 72. Despite these promising results, there is no evidence that fat transfer replaces the use of immunosuppressives in active facial morphea lesions. Therefore, fat transfer should only be used once active disease is demonstrably controlled with immunosuppressives or quiescent off therapy to avoid recurring tissue loss. Taken as a whole, treatment efficacy and benefit on life quality of interventions to mitigate damage are very poorly studied in morphea.

Topical therapy

Topical therapy may help limited and superficial forms of morphea, and can reduce itch.

- Topical steroids

- Tacrolimus ointment

- Calcipotriol ointment or cream. Two uncontrolled studies investigated topical calcipotriene 0.005% ointment, either with 73 or without occlusion 74. These studies included 31 patients and both studies reported beneficial effects in all patients. Lastly, an uncontrolled study with six patients reported efficacy of combination therapy with betamethasone dipropionate and calcipotriol 0.005% 75. Based on the literature, experts recommend topical calcipotriol 0.005% ointment, once or twice daily, with or without occlusion as an alternative topical therapy for superficial morphea. Additionally, topical calcipotriol 0.005% ointment may be prescribed combined with topical corticosteroid therapy.

- Imiquimod cream. A proof-of-concept study with topical imiquimod 5% cream reported effectiveness, measured by decrease of Dyspigmentation, Induration, Erythema and Telangiectasia (DIET) score and visual analog scale (VAS) score in nine pediatric patients 76. A second prospective vehicle-controlled study with 25 adult patients confirmed these results. Imiquimod 5% cream was superior to vehicle in reducing Dyspigmentation, Induration, Erythema and Telangiectasia (DIET) scores at months 3, 6, 9, and 12 77. Both prospective studies reported no study withdrawals and adverse effects were minimal. Several case reports and series confirm the beneficial effects of imiquimod 5% 78, 79. Despite these positive study results, German guidelines do not recommend the use of imiquimod 5% cream 24.

Phototherapy

Phototherapy can soften morphea and has anti-inflammatory effects.

Different wavelengths of ultraviolet radiation can be used.

- UVA1 penetrates most deeply and is hence useful when deeper subcutaneous tissues are involved, but is rarely available.

- Topical or systemic photochemotherapy (PUVA, ie, psoralen + UVA) may be helpful.

- Narrowband UVB is less effective, as it only penetrates superficially.

Systemic treatment

Systemic treatment is intended to prevent progression and switch off the active disease process. It is usually needed for at least 2 to 4 years, but relapse can occur. Specific treatment decisions in morphea are guided by the subtype of morphea and its severity.

- Methotrexate. Methotrexate, with or without the combination of intravenous methylprednisolone and/or oral systemic corticosteroid, is the most reported systemic treatment for morphea. Best evidence results from a double-blind randomized controlled trial with 70 pediatric morphea patients, which investigated oral Methotrexate (15 mg/m²/week, max 20 mg) versus placebo for 12 months 30. Both arms received an oral systemic corticosteroid (prednisone, starting dose 1 mg/kg/day, max 50 mg, followed by tapering) for the first 3 months. Reported outcome measures consisted of a computerized skin score rate and infrared thermography. Improvements in outcome measures at month 12 could only be observed in the methotrexate treatment arm, whereas the placebo arm showed worsening 30. Two prospective non-controlled studies investigated methotrexate in combination with intravenous methylprednisolone 80 or oral systemic corticosteroid 81 in children. One study included ten pediatric patients who received subcutaneous Methotrexate 0.3–0.6 mg/kg/week (max 20 mg/week), of whom nine patients simultaneously received intravenous methylprednisolone (30 mg/kg for 3 days, monthly for 3 months). At the last follow-up visit, all patients who continued (n = 9) had inactive skin lesions 80. The second study investigated subcutaneous Methotrexate (1 mg/kg/week, max 25 mg) in combination with an oral systemic corticosteroid (prednisone 2 mg/kg/day, maximum 60 mg/day followed by tapering) in 36 pediatric patients. All patients demonstrated significant improvement in mLoSSI and PhysGA-A at a median of 1.77 months 81. In conclusion, methotrexate is an effective treatment for morphea. However, no comparative studies between methotrexate monotherapy and methotrexate plus systemic corticosteroid have been reported. Therefore, no recommendations can be given as to whether methotrexate should be applied with or without systemic corticosteroid. However, either oral systemic corticosteroid or intravenous methylprednisolone should be added to methotrexate in the case of severe disease, rapidly progressive disease, or in the presence of (looming) contractures. Optimal timing of systemic treatment discontinuation remains a difficult aspect in therapeutic management.

- Folic Acid Supplementation: A retrospective analysis of methotrexate treatment in 107 adult patients showed that folic acid (5–10 mg once a week) protected against methotrexate discontinuation due to adverse events 82. Additionally, folic acid (0.4–1 mg/day) or folinic acid (5 mg/week) is recommended by Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance 83.

- Systemic corticosteroids. One open study investigated an oral systemic corticosteroid (prednisone, starting dose 0.5–1 mg/kg/day followed by tapering) in 17 patients with severe morphea. Patients were treated for 5 to 70 months 84. This study reported a rapid response. However, in six patients (35%), disease relapse was observed after treatment discontinuation 84. Additionally, a retrospective study with 28 adult patients reported a favorable response in 24 patients (86%) with an oral systemic corticosteroid (prednisone, starting dose 0.3–1.0 mg/kg/day) 85. Patients were treated for 3–39 months. Similar to the first study, recurrence rate was 45% after treatment discontinuation 85. High recurrence rates combined with an unfavorable long-term side-effect profile leads to the recommendation that oral systemic corticosteroid monotherapy is no viable long-term treatment option for morphea. Intravenous methylprednisolone (IVMP) has only been investigated in combination with methotrexate.

- Mycophenolate mofetil. Two studies reported mycophenolate mofetil in severe refractory morphea 86, 87. The first study retrospectively described ten methotrexate- and corticosteroid-refractory pediatric morphea patients who were treated with mycophenolate mofetil (600–1200 mg/m²/day) 86. Six out of ten patients received mycophenolate mofetil combined with methotrexate treatment. Arrest of disease progression was reported in eight patients (80%) a reduction of erythema in seven (70%), skin softening in nine (90%), and extracutaneous manifestations in four patients (40%). mycophenolate mofetil was well tolerated in all patients 86. The second study retrospectively described mycophenolate mofetil in seven morphea patients (three adults and four children) 87. Doses ranged from 500 to 2500 mg. This study reported disease remission in four patients (57%) and maintenance of disease remission in one patient (14%). In the remaining two patients (29%), mycophenolate mofetil treatment was discontinued due to disease progression or side effects 87. Despite the limited evidence for mycophenolate mofetil in morphea, two studies showed extensive experience with mycophenolate mofetil in large proportions of involved care providers 88. Based on current evidence, experts recommend mycophenolate mofetil (adults 1000 mg twice daily; children 600–1200 mg/m²/day twice daily) as an alternative to methotrexate.

Superficial limited morphea — mild

- Topical therapy

- Phototherapy (UVA1, nbUVB, PUVA)

Superficial generalized or adult onset linear morphea — moderate

- Topical therapies AND phototherapy

- Systemic therapy

Deep forms of morphea and paediatric onset linear morphea — severe

- Methotrexate +/- systemic corticosteroids (IV pulsed &/or oral)

- Mycophenolate mofetil +/- corticosteroids (IV pulsed &/or oral)

- Combination therapies

- Combine 1st and 2nd line treatments

- Add hydroxychloroquine

- Add phototherapy (UVA1 or PUVA if available)

- Other options

- Ciclosporin

- Abatacept

- Tocilizumab

- Extracorporeal photopheresis

- Other experimental and reported therapies

Physiotherapy to improve joint mobility should be undertaken with caution in active morphea, as the resultant trauma may potentially act as an ongoing disease trigger.

In some cases, surgery may be of benefit, such as autologous fat transfer, to improve atrophy.

Monitoring treatment response

Disease progression and treatment response can be monitored using photographs, the localized scleroderma cutaneous assessment tool and other highly specialized tests, such as infrared thermography.

Morphea prognosis

Morphea is characterized by relapsing and remitting periods of activity, marked by inflammation and fibrosis, and damage which produces atrophy 1. Unchecked disease activity in morphea can lead to permanent deformity and functional impairment, and therefore early diagnosis and treatment are imperative to minimize damage 4. Patches of morphea that are superficial may be relatively benign, and the prognosis is good 6. Still, some variants of morphea tend to involve subcutaneous tissue, muscle tissue, and bone, resulting in functional disabilities and cosmetic problems. Many children with linear morphea can develop joint contractures and limb length discrepancies 6.

References- Abbas L, Joseph A, Kunzler E, Jacobe HT. Morphea: progress to date and the road ahead. Ann Transl Med. 2021 Mar;9(5):437. doi: 10.21037/atm-20-6222

- Khatri S, Torok KS, Mirizio E, Liu C, Astakhova K. Autoantibodies in Morphea: An Update. Front Immunol. 2019 Jul 9;10:1487. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2019.01487

- Mertens JS, Seyger MMB, Thurlings RM, Radstake TRDJ, de Jong EMGJ. Morphea and Eosinophilic Fasciitis: An Update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017 Aug;18(4):491-512. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0269-x

- Florez-Pollack S, Kunzler E, Jacobe HT. Morphea: Current concepts. Clin Dermatol 2018;36:475-86. 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2018.04.005

- Careta MF, Romiti R. Localized scleroderma: clinical spectrum and therapeutic update. An Bras Dermatol. 2015 Jan-Feb;90(1):62-73. doi: 10.1590/abd1806-4841.20152890

- Penmetsa GK, Sapra A. Morphea. [Updated 2022 Jun 12]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559010

- Li SC. Scleroderma in Children and Adolescents: Localized Scleroderma and Systemic Sclerosis. Pediatr Clin North Am 2018;65:757-81. 10.1016/j.pcl.2018.04.002

- Sapra A, Dix R, Bhandari P, Mohammed A, Ranjit E. A Case of Extensive Debilitating Generalized Morphea. Cureus. 2020 May 14;12(5):e8117. doi: 10.7759/cureus.8117

- Morphoea. https://dermnetnz.org/topics/morphoea

- Herrick AL, Ennis H, Bhushan M, Silman AJ, Baildam EM. Incidence of childhood linear scleroderma and systemic sclerosis in the UK and Ireland. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2010 Feb;62(2):213-8. doi: 10.1002/acr.20070

- Silman A, Jannini S, Symmons D, Bacon P. An epidemiological study of scleroderma in the West Midlands. Br J Rheumatol. 1988 Aug;27(4):286-90. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/27.4.286

- Peterson LS, Nelson AM, Su WP, Mason T, O’Fallon WM, Gabriel SE. The epidemiology of morphea (localized scleroderma) in Olmsted County 1960-1993. J Rheumatol. 1997 Jan;24(1):73-80.

- Zulian F, Athreya BH, Laxer R, Nelson AM, Feitosa de Oliveira SK, Punaro MG, et al. Juvenile localized scleroderma: clinical and epidemiological features in 750 children. An international study. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2006;45(5):614–20. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kei251

- Kreuter A, Wischnewski J, Terras S, Altmeyer P, Stücker M, Gambichler T. Coexistence of lichen sclerosus and morphea: a retrospective analysis of 472 patients with localized scleroderma from a German tertiary referral center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2012 Dec;67(6):1157-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2012.04.003

- Christen-Zaech S, Hakim MD, Afsar FS, Paller AS. Pediatric morphea (localized scleroderma): review of 136 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008 Sep;59(3):385-96. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2008.05.005

- Mertens JS, Seyger MM, Kievit W, Hoppenreijs EP, Jansen TL, van de Kerkhof PC, Radstake TR, de Jong EM. Disease recurrence in localized scleroderma: a retrospective analysis of 344 patients with paediatric- or adult-onset disease. Br J Dermatol. 2015 Mar;172(3):722-8. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13514

- Leitenberger JJ, Cayce RL, Haley RW, Adams-Huet B, Bergstresser PR, Jacobe HT. Distinct autoimmune syndromes in morphea: a review of 245 adult and pediatric cases. Arch Dermatol. 2009 May;145(5):545-50. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2009.79

- Condie D, Grabell D, Jacobe H. Comparison of outcomes in adults with pediatric-onset morphea and those with adult-onset morphea: a cross-sectional study from the morphea in adults and children cohort. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014 Dec;66(12):3496-504. doi: 10.1002/art.38853

- Dehen L, Roujeau JC, Cosnes A, Revuz J. Internal involvement in localized scleroderma. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994 Sep;73(5):241-5. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199409000-00002

- Rosenberg AM, Uziel Y, Krafchik BR, Hauta SA, Prokopchuk PA, Silverman ED, Laxer RM. Antinuclear antibodies in children with localized scleroderma. J Rheumatol. 1995 Dec;22(12):2337-43.

- Takehara K, Moroi Y, Nakabayashi Y, Ishibashi Y. Antinuclear antibodies in localized scleroderma. Arthritis Rheum. 1983 May;26(5):612-6. doi: 10.1002/art.1780260506

- Martini G, Fadanelli G, Agazzi A, et al. Disease course and long-term outcome of juvenile localized scleroderma: Experience from a single pediatric rheumatology Centre and literature review. Autoimmun Rev 2018;17:727-34. 10.1016/j.autrev.2018.02.004

- Laxer RM, Zulian F. Localized scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2006 Nov;18(6):606-13. doi: 10.1097/01.bor.0000245727.40630.c3

- Kreuter A, Krieg T, Worm M, Wenzel J, Moinzadeh P, Kuhn A, Aberer E, Scharffetter-Kochanek K, Horneff G, Reil E, Weberschock T, Hunzelmann N. German guidelines for the diagnosis and therapy of localized scleroderma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2016 Feb;14(2):199-216. doi: 10.1111/ddg.12724

- Knobler R, Moinzadeh P, Hunzelmann N, et al. European Dermatology Forum S1-guideline on the diagnosis and treatment of sclerosing diseases of the skin, Part 1: localized scleroderma, systemic sclerosis and overlap syndromes. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 2017;31:1401-24. 10.1111/jdv.14458

- Prasad S, Zhu JL, Schollaert-Fitch K, et al. Characterizing morphea subsets using a multi-center, prospective, cross-sectional analysis of morphea in adults and children. J Investig Dermatol 2020;140:S73. 10.1016/j.jid.2020.03.549

- Kunzler E, Florez-Pollack S, Teske N, et al. Linear morphea: Clinical characteristics, disease course, and treatment of the Morphea in Adults and Children cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol 2019;80:1664-70.e1. 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.01.050

- Mazori DR, Wright NA, Patel M, Liu SW, Ramachandran SM, Franks AG Jr, Vleugels RA, Femia AN. Characteristics and treatment of adult-onset linear morphea: A retrospective cohort study of 61 patients at 3 tertiary care centers. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Mar;74(3):577-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.09.069

- Piram M, McCuaig CC, Saint-Cyr C, Marcoux D, Hatami A, Haddad E, Powell J. Short- and long-term outcome of linear morphoea in children. Br J Dermatol. 2013 Dec;169(6):1265-71. doi: 10.1111/bjd.12606. Erratum in: Br J Dermatol. 2014 Apr;170(4):999. Dosage error in article text.

- Zulian F, Martini G, Vallongo C, Vittadello F, Falcini F, Patrizi A, Alessio M, La Torre F, Podda RA, Gerloni V, Cutrone M, Belloni-Fortina A, Paradisi M, Martino S, Perilongo G. Methotrexate treatment in juvenile localized scleroderma: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2011 Jul;63(7):1998-2006. doi: 10.1002/art.30264

- Mirsky L, Chakkittakandiyil A, Laxer RM, O’Brien C, Pope E. Relapse after systemic treatment in paediatric morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 2012 Feb;166(2):443-5. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2011.10535.x

- Vasquez R, Jabbar A, Khan F, Buethe D, Ahn C, Jacobe H. Recurrence of morphea after successful ultraviolet A1 phototherapy: A cohort study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014 Mar;70(3):481-8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.10.018

- Zannin ME, Martini G, Athreya BH, Russo R, Higgins G, Vittadello F, Alpigiani MG, Alessio M, Paradisi M, Woo P, Zulian F; Juvenile Scleroderma Working Group of the Pediatric Rheumatology European Society (PRES). Ocular involvement in children with localised scleroderma: a multi-centre study. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007 Oct;91(10):1311-4. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2007.116038

- Tollefson MM, Witman PM. En coup de sabre morphea and Parry-Romberg syndrome: a retrospective review of 54 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2007 Feb;56(2):257-63. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.10.959

- Trainito S, Favero L, Martini G, Pedersen TK, Favero V, Herlin T, Zulian F. Odontostomatologic involvement in juvenile localised scleroderma of the face. J Paediatr Child Health. 2012 Jul;48(7):572-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2012.02435.x

- O’Flynn S, Kinirons M. Parry-Romberg syndrome: a report of the dental findings in a child followed up for 9 years. Int J Paediatr Dent. 2006 Jul;16(4):297-301. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-263X.2006.00730.x

- Tolkachjov SN, Patel NG, Tollefson MM. Progressive hemifacial atrophy: a review. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2015 Apr 1;10:39. doi: 10.1186/s13023-015-0250-9

- George R, George A, Kumar TS. Update on Management of Morphea (Localized Scleroderma) in Children. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2020 Mar 9;11(2):135-145. doi: 10.4103/idoj.IDOJ_284_19

- Badea I, Taylor M, Rosenberg A, Foldvari M. Pathogenesis and therapeutic approaches for improved topical treatment in localized scleroderma and systemic sclerosis. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2009 Mar;48(3):213-21. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/ken405

- Zulian F, Vallongo C, Woo P, Russo R, Ruperto N, Harper J, Espada G, Corona F, Mukamel M, Vesely R, Musiej-Nowakowska E, Chaitow J, Ros J, Apaz MT, Gerloni V, Mazur-Zielinska H, Nielsen S, Ullman S, Horneff G, Wouters C, Martini G, Cimaz R, Laxer R, Athreya BH; Juvenile Scleroderma Working Group of the Pediatric Rheumatology European Society (PRES). Localized scleroderma in childhood is not just a skin disease. Arthritis Rheum. 2005 Sep;52(9):2873-81. doi: 10.1002/art.21264

- Amaral TN, Marques Neto JF, Lapa AT, et al. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma en coup de sabre. Autoimmune Dis 2012;2012:719685. 10.1155/2012/719685

- Kister I, Inglese M, Laxer RM, et al. Neurologic manifestations of localized scleroderma: a case report and literature review. Neurology 2008;71:1538-45. 10.1212/01.wnl.0000334474.88923.e3

- Chiu YE, Vora S, Kwon EKM, et al. A significant proportion of children with morphea en coup de sabre and Parry-Romberg syndrome have neuroimaging findings. Pediatr Dermatol 2012;29:738-48. 10.1111/pde.12001

- Amaral TN, Peres FA, Lapa AT, et al. Neurologic involvement in scleroderma: a systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013;43:335-47. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2013.05.002

- Lis-Święty A, Brzezińska-Wcisło L, Arasiewicz H. Neurological abnormalities in localized scleroderma of the face and head: a case series study for evaluation of imaging findings and clinical course. Int J Neurosci 2017;127:835-9. 10.1080/00207454.2016.1244823

- Laxer RM, Zulian F. Localized scleroderma. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2006;18:606-13. 10.1097/01.bor.0000245727.40630.c3

- Martini G, Ramanan AV, Falcini F, et al. Successful treatment of severe or methotrexate-resistant juvenile localized scleroderma with mycophenolate mofetil. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2009;48:1410-3. 10.1093/rheumatology/kep244

- Abbas LF, O’Brien JC, Goldman S, et al. A Cross-sectional Comparison of Magnetic Resonance Imaging Findings and Clinical Assessment in Patients With Morphea. JAMA Dermatol 2020;156:590-2. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0036

- Teske N, Welser J, Jacobe H. Skin mapping for the classification of generalized morphea. J Am Acad Dermatol 2018;78:351-7. 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.08.052

- Jacobe HT, Prasad S, Black SM, et al. 543 Clinical and demographic features of morphea patients with mucocutaneous involvement: A cross sectional study from The Morphea of Adults and Children (MAC Cohort). J Investig Dermatol 2020;140:S74. 10.1016/j.jid.2020.03.552

- Lutz V, Frances C, Bessis D, et al. High frequency of genital lichen sclerosus in a prospective series of 76 patients with morphea: toward a better understanding of the spectrum of morphea. Arch Dermatol 2012;148:24-8. 10.1001/archdermatol.2011.305

- Hørberg M, Lauesen SR, Daugaard-Jensen J, et al. Linear scleroderma en coup de sabre including abnormal dental development. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent 2015;16:227-31. 10.1007/s40368-014-0148-6

- Wang P, Guo W, Liu S. A rare case of juvenile localised scleroderma with intra-oral and dental involvement. Exp Ther Med 2015;10:2213-5. 10.3892/etm.2015.2791

- Abbas LF, Coias J, Jacobe HT, et al. Hyaluronidase injections for treatment of symptomatic pansclerotic morphea-induced microstomia. JAAD Case Rep 2019;5:871-3. 10.1016/j.jdcr.2019.08.004

- Van der Veken D, De Haes P, Hauben E, et al. A rare cause of gingival recession: morphea with intra-oral involvement. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol 2015;119:e257-64. 10.1016/j.oooo.2015.02.002

- Fledelius HC, Danielsen PL, Ullman S. Ophthalmic findings in linear scleroderma manifesting as facial en coup de sabre. Eye (London, England) 2018;32:1688-96. 10.1038/s41433-018-0137-9

- Succaria F, Kurban M, Kibbi AG, Abbas O. Clinicopathological study of 81 cases of localized and systemic scleroderma. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Feb;27(2):e191-6. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-3083.2012.04581.x

- Torres JE, Sánchez JL. Histopathologic differentiation between localized and systemic scleroderma. Am J Dermatopathol. 1998 Jun;20(3):242-5. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199806000-00003

- van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, Tyndall A, Matucci-Cerinic M, Naden RP, Medsger TA Jr, Carreira PE, Riemekasten G, Clements PJ, Denton CP, Distler O, Allanore Y, Furst DE, Gabrielli A, Mayes MD, van Laar JM, Seibold JR, Czirjak L, Steen VD, Inanc M, Kowal-Bielecka O, Müller-Ladner U, Valentini G, Veale DJ, Vonk MC, Walker UA, Chung L, Collier DH, Csuka ME, Fessler BJ, Guiducci S, Herrick A, Hsu VM, Jimenez S, Kahaleh B, Merkel PA, Sierakowski S, Silver RM, Simms RW, Varga J, Pope JE. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum. 2013 Nov;65(11):2737-47. doi: 10.1002/art.38098

- Kroft EB, Groeneveld TJ, Seyger MM, de Jong EM. Efficacy of topical tacrolimus 0.1% in active plaque morphea: randomized, double-blind, emollient-controlled pilot study. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2009;10(3):181-7. doi: 10.2165/00128071-200910030-00004

- Mancuso G, Berdondini RM. Localized scleroderma: response to occlusive treatment with tacrolimus ointment. Br J Dermatol. 2005 Jan;152(1):180-2. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2004.06318.x

- Stefanaki C, Stefanaki K, Kontochristopoulos G, Antoniou C, Stratigos A, Nicolaidou E, Gregoriou S, Katsambas A. Topical tacrolimus 0.1% ointment in the treatment of localized scleroderma. An open label clinical and histological study. J Dermatol. 2008 Nov;35(11):712-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1346-8138.2008.00552.x

- Chu CH, Cheng YP, Liang CW, Chiu HC, Jee SH, Lisa Chan JY, Yu Y. Radiation recall dermatitis induced by topical tacrolimus for post-irradiation morphea. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2017 Feb;31(2):e80-e81. doi: 10.1111/jdv.13739

- Prasad S, Coias J, Chen HW, et al. Utilizing UVA-1 Phototherapy. Dermatol Clin 2020;38:79-90. 10.1016/j.det.2019.08.011

- Kreuter A, Hyun J, Stücker M, Sommer A, Altmeyer P, Gambichler T. A randomized controlled study of low-dose UVA1, medium-dose UVA1, and narrowband UVB phototherapy in the treatment of localized scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006 Mar;54(3):440-7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2005.11.1063

- Pileri A, Raone B, Raboni R, Giudice V, Patrizi A. Generalized morphea successfully treated with extracorporeal photochemotherapy (ECP). Dermatol Online J. 2014 Jan 15;20(1):21258.

- Arthur M, Fett NM, Latour E, et al. Evaluation of the Effectiveness and Tolerability of Mycophenolate Mofetil and Mycophenolic Acid for the Treatment of Morphea. JAMA Dermatol 2020;156:521-8. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0035

- Maybury CM, Jabbar-Lopez ZK, Wong T, et al. Methotrexate and liver fibrosis in people with psoriasis: a systematic review of observational studies. Br J Dermatol 2014;171:17-29. 10.1111/bjd.12941

- Fatimah N, Salim B, Nasim A, et al. Frequency of methotrexate intolerance in rheumatoid arthritis patients using methotrexate intolerance severity score (MISS questionnaire). Clin Rheumatol 2016;35:1341-5. 10.1007/s10067-016-3243-8

- van Dijkhuizen EH, Bulatović Ćalasan M, Pluijm SM, et al. Prediction of methotrexate intolerance in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a prospective, observational cohort study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J 2015;13:5. 10.1186/s12969-015-0002-3

- O’Brien JC, Nymeyer H, Green A, et al. Changes in Disease Activity and Damage Over Time in Patients With Morphea. JAMA Dermatol 2020;156:513-20. 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0034

- Bellini E, Grieco MP, Raposio E. The science behind autologous fat grafting. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2017;24:65-73. 10.1016/j.amsu.2017.11.001

- Cunningham BB, Landells ID, Langman C, Sailer DE, Paller AS. Topical calcipotriene for morphea/linear scleroderma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1998 Aug;39(2 Pt 1):211-5. doi: 10.1016/s0190-9622(98)70077-5

- Kreuter A, Gambichler T, Avermaete A, Jansen T, Hoffmann M, Hoffmann K, Altmeyer P, von Kobyletzki G, Bacharach-Buhles M. Combined treatment with calcipotriol ointment and low-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in childhood morphea. Pediatr Dermatol. 2001 May-Jun;18(3):241-5. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.2001.018003241.x

- Dytoc MT, Kossintseva I, Ting PT. First case series on the use of calcipotriol-betamethasone dipropionate for morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 2007 Sep;157(3):615-8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2007.07971.x

- Pope E, Doria AS, Theriault M, Mohanta A, Laxer RM. Topical imiquimod 5% cream for pediatric plaque morphea: a prospective, multiple-baseline, open-label pilot study. Dermatology (Basel, Switzerland) 2011;223(4):363–9. doi:10.1159/000335560

- Dytoc M, Wat H, Cheung-Lee M, Sawyer D, Ackerman T, Fiorillo L. Evaluation of the efficacy and safety of topical imiquimod 5% for plaque-type morphea: a multicenter, prospective, vehicle-controlled trial. J Cutan Med Surg. 2015 Mar-Apr;19(2):132-9. doi: 10.2310/7750.2014.14072

- Campione E, Paternò EJ, Diluvio L, Orlandi A, Bianchi L, Chimenti S. Localized morphea treated with imiquimod 5% and dermoscopic assessment of effectiveness. J Dermatolog Treat. 2009;20(1):10-3. doi: 10.1080/09546630802132668

- Dytoc M, Ting PT, Man J, Sawyer D, Fiorillo L. First case series on the use of imiquimod for morphoea. Br J Dermatol. 2005 Oct;153(4):815-20. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06776.x

- Uziel Y, Feldman BM, Krafchik BR, Yeung RS, Laxer RM. Methotrexate and corticosteroid therapy for pediatric localized scleroderma. J Pediatr. 2000 Jan;136(1):91-5. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(00)90056-8

- Torok KS, Arkachaisri T. Methotrexate and corticosteroids in the treatment of localized scleroderma: a standardized prospective longitudinal single-center study. J Rheumatol. 2012 Feb;39(2):286-94. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.110210

- Mertens JS, van den Reek JM, Kievit W, van de Kerkhof PC, Thurlings RM, Radstake TR, Seyger MM, de Jong EM. Drug Survival and Predictors of Drug Survival for Methotrexate Treatment in a Retrospective Cohort of Adult Patients with Localized Scleroderma. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016 Nov 2;96(7):943-947. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2411

- Li SC, Torok KS, Pope E, Dedeoglu F, Hong S, Jacobe HT, Rabinovich CE, Laxer RM, Higgins GC, Ferguson PJ, Lasky A, Baszis K, Becker M, Campillo S, Cartwright V, Cidon M, Inman CJ, Jerath R, O’Neil KM, Vora S, Zeft A, Wallace CA, Ilowite NT, Fuhlbrigge RC; Childhood Arthritis and Rheumatology Research Alliance (CARRA) Localized Scleroderma Workgroup. Development of consensus treatment plans for juvenile localized scleroderma: a roadmap toward comparative effectiveness studies in juvenile localized scleroderma. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2012 Aug;64(8):1175-85. doi: 10.1002/acr.21687

- Joly P, Bamberger N, Crickx B, Belaich S. Treatment of Severe Forms of Localized Scleroderma With Oral Corticosteroids: Follow-up Study on 17 Patients. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130(5):663–664. doi:10.1001/archderm.1994.01690050133027

- Amy de la Bretèque M, Rybojad M, Cordoliani F, Petit A, Juillard C, Flageul B, Bagot M, Bouaziz JD. Relapse of severe forms of adult morphea after oral corticosteroid treatment. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2013 Sep;27(9):1190-1. doi: 10.1111/jdv.12039

- Martini G, Ramanan AV, Falcini F, Girschick H, Goldsmith DP, Zulian F. Successful treatment of severe or methotrexate-resistant juvenile localized scleroderma with mycophenolate mofetil. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2009;48(11):1410–3. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/kep244

- Mertens JS, Marsman D, van de Kerkhof PC, Hoppenreijs EP, Knaapen HK, Radstake TR, de Jong EM, Seyger MM. Use of Mycophenolate Mofetil in Patients with Severe Localized Scleroderma Resistant or Intolerant to Methotrexate. Acta Derm Venereol. 2016 May;96(4):510-3. doi: 10.2340/00015555-2297

- Hawley DP, Pain CE, Baildam EM, Murphy R, Taylor AE, Foster HE. United Kingdom survey of current management of juvenile localized scleroderma. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2014;53(10):1849–54. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keu212