What is mucositis

Mucositis also called oral mucositis, is when your mouth or gut is sore and inflamed. Oral mucositis is a common side effect of chemotherapy and radiation therapy for cancer 1. Typically symptoms may include mouth pain or mouth ulcers. Mucositis can be very unpleasant, but usually stops in a few weeks. They usually begin around 1 to 2 weeks after starting cancer treatment. Follow your health care provider’s instructions on how to care for your mouth.

Erythematous mucositis typically appears 7 to 10 days after initiation of high-dose cancer therapy. Clinicians should be alert to the potential for increased toxicity with escalating dose or treatment duration in clinical trials that demonstrate gastrointestinal mucosal toxicity. High-dose chemotherapy, such as that used in the treatment of leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant regimens, may produce severe mucositis. Mucositis is self-limited when uncomplicated by infection and typically heals within 2 to 4 weeks after cessation of cytotoxic chemotherapy.

In an effort to standardize measurements of mucosal integrity, oral assessment scales have been developed to grade the level of stomatitis by characterizing alterations in lips, tongue, mucous membranes, gingiva, teeth, pharynx, quality of saliva, and voice 2. Specific instruments of assessment have been developed to evaluate the observable and functional dimensions of mucositis. These evaluative tools vary in complexity.

Things you can do to help

If you’re having cancer treatment, there are some things you can do to help prevent and ease mucositis.

DO

- brush your teeth with a soft toothbrush at least twice a day

- floss once a day

- rinse your mouth with warm water (or water mixed with a bit of salt) several times a day

- suck on crushed ice or ice lollies

- eat soft, moist foods (try adding gravy or sauces to meals)

- drink plenty of water

- chew sugar-free gum (this can help keep your mouth moist)

DON’T

- DON’T use mouthwashes from shops without speaking to a pharmacist, nurse or doctor – they might irritate your mouth

- DON’T eat crunchy, rough or sharp foods like crisps

- DON’T eat hot, spicy or salty foods

- DON’T eat acidic foods like tomatoes, oranges or lemons

- DON’T drink hot drinks (like tea and coffee), fizzy drinks or alcohol

- DON’T smoke

- DON’T take painkillers without speaking to a pharmacist, nurse or doctor

Mucositis causes

Risk of oral mucositis has historically been characterized by treatment-based and patient-based variables 3. The current model of oral mucositis involves a complex trajectory of molecular, cellular, and tissue-based changes. There is increasing evidence of genetic governance of this injury 4, characterized in part by upregulation of nuclear factor kappa beta and inflammatory cytokines (e.g., tumor necrosis factor-alpha) and interleukin-1 in addition to epithelial basal cell injury. Comprehensive knowledge of the molecular-based causation of the lesion has contributed to targeted drug development for clinical use 5. The pipeline of new drugs in development (e.g., recombinant human intestinal trefoil factor 6 may lead to strategic new advances in the ability of clinicians to customize the prevention and treatment of oral mucositis in the future 7.

Erythematous mucositis typically appears 7 to 10 days after initiation of high-dose cancer therapy. Clinicians should be alert to the potential for increased toxicity with escalating dose or treatment duration in clinical trials that demonstrate gastrointestinal mucosal toxicity. High-dose chemotherapy, such as that used in the treatment of leukemia and hematopoietic stem cell transplant regimens, may produce severe mucositis. Mucositis is self-limited when uncomplicated by infection and typically heals within 2 to 4 weeks after cessation of cytotoxic chemotherapy.

Radiation-induced oral mucositis occurs in up to 80% of head and neck cancer irradiated patients and reaches up to 100% in patients with altered fractionation head and neck cancer. Radiation-induced oral mucositis of grade 3 and 4 have been recorded in 56% of head and neck cancer patients treated with radiotherapy 8. Many risk factors have been identified for radiation-induced oral mucositis. These risk factors include concomitant chemotherapy, bad oral hygiene, below average nutritional stratus, lack of antibiotic use at early stage mucositis, and smoking 9. June Eilers and Rita Million 10 have summarized the patient-linked factors leading to increased risk for radiation-induced oral mucositis. They found that very young age, female gender, poor oral health and hygiene, decreased saliva secretion, low BMI, poor renal function with elevated serum creatinine level, smoking, and history of RIOM are risk factors predicting the development of radiation-induced oral mucositis in head and neck cancer patients 10.

Systematic assessment of the oral cavity following treatment permits early identification of lesions 11. Oral hygiene and other supportive care measures are important to minimizing the severity of the lesion.

Mucositis grading

In an effort to standardize measurements of mucosal integrity, oral assessment scales have been developed to grade the level of stomatitis by characterizing alterations in lips, tongue, mucous membranes, gingiva, teeth, pharynx, quality of saliva, and voice 12. Specific instruments of assessment have been developed to evaluate the observable and functional dimensions of mucositis. These evaluative tools vary in complexity.

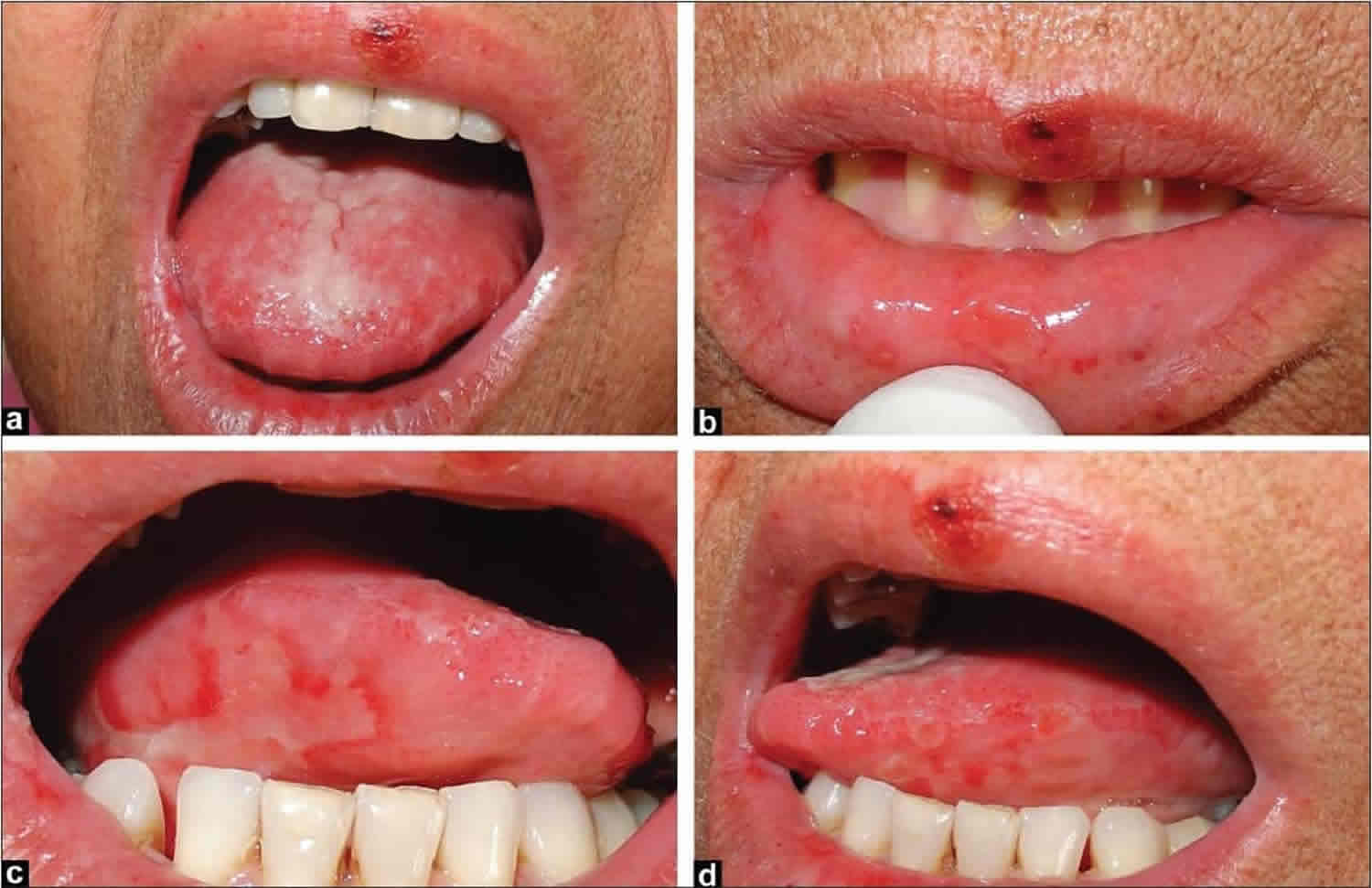

There has been more than one grading scale for oral mucositis 13. Table 1 shows the comparison of different radiation-induced oral mucositis scoring scales 14. The World Health Organization (WHO) Oral Toxicity Scale measures the anatomical, symptomatic, and functional elements of oral mucositis (Figure 1). The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group determined the acute radiation morbidity scoring criteria for mucous membranes. Finally, the Western Consortium for Cancer Nursing Research describes only the anatomical changes associated with oral mucositis 15.

The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group developed the Acute Radiation Morbidity Scoring Criteria for the evaluation of radiation therapy effects (another criterion was generated for late effects of radiotherapy) 16. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC) scores chemotherapy-related side effects. The Radiation Therapy Oncology Group was gathered with the NCI-CTC to produce version 2.0, which has been used in all National Cancer Institute clinical trials since March 1998 (Table 2) 17.

Table 1. Shows the comparison of different radiation-induced oral mucositis scoring scales

Table 2. Toxicity grading of oral mucositis (OM) according to World Health Organization (WHO) and National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria (NCI-CTC) criteria

Figure 1. Mucositis grading

[Source 13 ]Mucositis symptoms

When you have mucositis, you may have symptoms such as:

- Mouth pain.

- Mouth sores or ulcers.

- Difficulty swallowing, eating or talking.

- Dry mouth and lips.

- Diarrhea, bleeding from your bottom, or pain when pooing

- Infection.

- Bleeding, if you are getting chemotherapy. Radiation therapy usually does not lead to bleeding.

With chemotherapy, mucositis heals by itself when there is no infection. Healing usually takes 2 to 4 weeks. Mucositis caused by radiation therapy usually lasts 6 to 8 weeks, depending on how long you have radiation treatment.

Oral mucositis treatment

Mucositis should get better within a few weeks of finishing cancer treatment.

Your care team can offer treatments to ease mucositis, such as:

- mouthwashes that clean, numb and protect your mouth

- painkillers

- sprays or gels to keep your mouth moist (saliva substitutes)

- medicines to stop diarrhea or reduce soreness inside your bottom (rectum)

Take good care of your mouth during cancer treatment. Not doing so can lead to an increase in bacteria in your mouth. The bacteria can cause infection in your mouth, which can spread to other parts of your body.

- Brush your teeth and gums 2 or 3 times a day for 2 to 3 minutes each time.

- Use a toothbrush with soft bristles.

- Use a toothpaste with fluoride.

- Let your toothbrush air dry between brushings.

- If toothpaste makes your mouth sore, brush with a solution of 1 teaspoon (5 grams) of salt mixed with 4 cups (1 liter) of water. Pour a small amount into a clean cup to dip your toothbrush into each time you brush.

- Floss gently once a day.

Rinse your mouth 5 or 6 times a day for 1 to 2 minutes each time. Use one of the following solutions when you rinse:

- 1 teaspoon (5 grams) of salt in 4 cups (1 liter) of water

- 1 teaspoon (5 grams) of baking soda in 8 ounces (240 milliliters) of water

- One half teaspoon (2.5 grams) of salt and 2 tablespoons (30 grams) of baking soda in 4 cups (1 liter) of water

Don’t use rinses that have alcohol in them. You may use an antibacterial rinse 2 to 4 times a day for gum disease.

To further take care of your mouth:

- Don’t eat foods or drink beverages that have a lot of sugar in them. They may cause tooth decay.

- Use lip care products to keep your lips from drying and cracking.

- Sip water to ease dry mouth.

- Eat sugar-free candy or chew sugar-free gum to help keep your mouth moist.

- Stop wearing your dentures if they cause you to get sores on your gums.

Relieving Pain

Ask your doctor about treatments you can use in your mouth, including:

- Bland rinses

- Mucosal coating agents

- Water-soluble lubricating agents, including artificial saliva

- Pain medicine

Your doctor may also give you pills for pain or medicine to fight infection in your mouth.

Mucositis treatment guidelines

Updated guidelines from the American Society of Clinical Oncology for the prevention and treatment of mucositis were published in 2007 18 and include the following:

- Palifermin for oral mucositis associated with stem cell transplantation.

- Amifostine for radiation proctitis.

- Cryotherapy for high-dose-melphalan–induced mucositis.

Specific recommendations against specific practices include the following:

- No systemic glutamine for the prevention of gastrointestinal mucositis.

- No sucralfate or antibiotic lozenges for radiation-induced mucositis.

- No granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor mouthwashes.

Palifermin (Kepivance), also known as keratinocyte growth factor-1, has been approved to decrease the incidence and duration of severe oral mucositis in patients with hematologic cancers undergoing conditioning with high-dose chemotherapy, with or without radiation therapy, followed by hematopoietic stem cell rescue 5. The standard dosing regimen is three daily doses before conditioning and three additional daily doses starting on day 0 (day of transplant). Palifermin has also been shown in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial to reduce the incidence of oral mucositis in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with fluorouracil-based chemotherapy 19. In addition, a single dose of palifermin prevented severe oral mucositis in patients who had sarcoma and were receiving doxorubicin-based chemotherapy 20.

In two randomized, placebo-controlled trials conducted in head/neck cancer patients undergoing postoperative chemoradiotherapy and in patients receiving definitive chemoradiotherapy for locally advanced head/neck cancer, intravenous palifermin administered weekly for 8 weeks decreased severe oral mucositis 21, as graded by providers using standard toxicity assessments and during multicycle chemotherapy 20. Patient-reported outcomes related to mouth and throat soreness and to treatment breaks or compliance were not significantly different between arms in either trial. In one study, opioid analgesic use was also not significantly different between arms 22.

Evidence from several studies has supported the potential efficacy of low-level laser therapy in addition to oral care to decrease the duration of chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis in children 23.

Mucositis Management

- Bland rinses:

- 0.9% saline solution.

- Sodium bicarbonate solution.

- 0.9% saline/sodium bicarbonate solution.

- Topical anesthetics:

- Lidocaine: viscous, ointments, sprays.

- Benzocaine: sprays, gels.

- 0.5% or 1.0% dyclonine hydrochloride (HCl).

- Diphenhydramine solution.

- Mucosal coating agents:

- Amphojel.

- Kaopectate.

- Hydroxypropyl methylcellulose film-forming agents (e.g., Zilactin).

- Gelclair (approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration [FDA] as a device).

- Analgesics:

- Benzydamine HCl topical rinse (not approved in the United States).

- Opioid drugs: oral, intravenous (e.g., bolus, continuous infusion, patient-controlled analgesia [PCA]), patches, transmucosal.

- Growth factor (keratinocyte growth factor-1):

- Palifermin (approved by the FDA in December 2004 to decrease the incidence and duration of severe oral mucositis in patients undergoing high-dose chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy followed by bone marrow transplant for hematologic cancers).

Management of oral mucositis via topical approaches should address efficacy, patient acceptance, and appropriate dosing. A stepped approach is typically used, with progression from one level to the next as follows:

- Bland rinses (e.g., 0.9% normal saline and/or sodium bicarbonate solutions).

- Mucosal coating agents (e.g., antacid solutions, kaolin solutions).

- Water-soluble lubricating agents, including artificial saliva for xerostomia.

- Topical anesthetics (e.g., viscous lidocaine, benzocaine sprays/gels, dyclonine rinses, diphenhydramine solutions).

- Cellulose film-forming agents for covering localized ulcerative lesions (e.g., hydroxypropyl cellulose).

Normal saline solution is prepared by adding approximately 1 tsp of table salt to 32 oz of water. The solution can be administered at room or refrigerated temperatures, depending on patient preference. The patient should rinse and swish approximately 1 tbsp, followed by expectoration; this can be repeated as often as necessary to maintain oral comfort. Sodium bicarbonate (1–2 tbsp/qt) can be added, if viscous saliva is present. Saline solution can enhance oral lubrication directly as well as by stimulating salivary glands to increase salivary flow.

A soft toothbrush that is replaced regularly should be used to maintain oral hygiene 18. Foam-swab brushes do not effectively clean teeth and should not be considered a routine substitute for a soft nylon-bristled toothbrush; additionally, the rough sponge surface may irritate and damage the mucosal surfaces opposite the tooth surfaces being brushed.

On the basis of nonoral mucosa wound-healing studies, the repeated use of hydrogen peroxide rinses for daily preventive oral hygiene is not recommended, especially if mucositis is present, because of the potential for damage to fibroblasts and keratinocytes, which can cause delayed wound healing 24. Using 3% hydrogen peroxide diluted 1:1 with water or normal saline to remove hemorrhagic debris may be helpful; however, this approach should only be used for 1 or 2 days because more extended use may impair timely healing of mucosal lesions associated with bleeding 25.

Focal topical application of anesthetic agents is preferred over widespread oral topical administration, unless the patient requires more extensive pain relief. Products such as the following may provide relief:

- 2% viscous lidocaine

- Diphenhydramine solution

- One of the many extemporaneously prepared mixtures combining the following coating agents with topical anesthetics:

- Milk of magnesia.

- Kaolin with pectin suspension.

- Mixtures of aluminum.

- Magnesium hydroxide suspensions (many antacids).

The use of compounded topical anesthetic rinses should be considered carefully relative to the cost of compounding these products versus their actual efficacy.

Irrigation should be performed before topical medication is applied because removal of debris and saliva allows for better coating of oral tissues and prevents material from accumulating. Frequent rinsing cleans and lubricates tissues, prevents crusting, and palliates painful gingiva and mucosa.

Systemic analgesics should be administered when topical anesthetic strategies are not sufficient for clinical relief. Opiates are typically used 26; the combination of chronic indwelling venous catheters and computerized drug administration pumps to provide patient-controlled analgesia has significantly increased the effectiveness of controlling severe mucositis pain while lowering the dose and side effects of narcotic analgesics. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs that affect platelet adhesion and damage gastric mucosa are contraindicated, especially if thrombocytopenia is present.

Although mucositis continues to be one of the dose-limiting toxicities of fluorouracil (5-FU), cryotherapy may be an option for preventing oral mucositis. Because 5-FU has a short half-life (5–20 minutes), patients are instructed to swish ice chips in their mouths for 30 minutes, beginning 5 minutes before 5-FU is administered 27. Oral cryotherapy has been studied in patients receiving high-dose melphalan conditioning regimens used with transplantation 28; further research is needed.

Many agents and protocols have been promoted for management or prevention of mucositis 29. Although not adequately supported by controlled clinical trials, allopurinol mouthwash and vitamin E have been cited as agents that decrease the severity of mucositis. Prostaglandin E2 was not effective as a prophylaxis of oral mucositis following bone marrow transplant, although studies indicate possible efficacy when prostaglandin E2 is administered via a different dosing protocol.

Mucositis prognosis

The general long-term prognosis is reasonably good since most lesions resolve within 2–4 weeks after stopping the radiation therapy or chemotherapy. Although oral mucositis is considered a self-limited injury in some patients, it could be a lethal injury in moderately to severely ill patients, which could lead to ICU admission with obligatory cessation of radiation therapy. Patient losses are a common event under these circumstances 30.

References- Lalla RV, Brennan MT, Schubert MM: Oral complications of cancer therapy. In: Yagiela JA, Dowd FJ, Johnson BS, et al., eds.: Pharmacology and Therapeutics for Dentistry. 6th ed. St. Louis, Mo: Mosby Elsevier, 2011, pp 782-98.

- The 20 item oral mucositis index: reliability and validity in bone marrow and stem cell transplant patients. Cancer Invest. 2002;20(7-8):893-903. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12449720

- Barasch A, Peterson DE: Risk factors for ulcerative oral mucositis in cancer patients: unanswered questions. Oral Oncol 39 (2): 91-100, 2003

- Hahn T, Zhelnova E, Sucheston L, et al.: A deletion polymorphism in glutathione-S-transferase mu (GSTM1) and/or theta (GSTT1) is associated with an increased risk of toxicity after autologous blood and marrow transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 16 (6): 801-8, 2010

- Spielberger R, Stiff P, Bensinger W, et al.: Palifermin for oral mucositis after intensive therapy for hematologic cancers. N Engl J Med 351 (25): 2590-8, 2004

- Peterson DE, Barker NP, Akhmadullina LI, et al.: Phase II, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study of recombinant human intestinal trefoil factor oral spray for prevention of oral mucositis in patients with colorectal cancer who are receiving fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 27 (26): 4333-8, 2009

- Peterson DE, Bensadoun RJ, Roila F, et al.: Management of oral and gastrointestinal mucositis: ESMO clinical recommendations. Ann Oncol 20 (Suppl 4): 174-7, 2009

- Elting LS, Cooksley CD, Chambers MS, Garden AS. Risk, outcomes, and costs of radiation-induced oral mucositis among patients with head-and-neck malignancies. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys (2007) 68(4):1110–20. doi:10.1016/j.ijrobp.2007.01.053

- Luo DH, Hong MH, Guo L, Cao KJ, Deng MQ, Mo HY. [Analysis of oral mucositis risk factors during radiotherapy for nasopharyngeal carcinoma patients and establishment of a discriminant model]. Ai Zheng (2005) 24(7):850–4.

- Eilers J, Million R. Prevention and management of oral mucositis in patients with cancer. Semin Oncol Nurs (2007) 23:201–12. doi:10.1016/j.soncn.2007.05.005

- Schubert MM, Williams BE, Lloid ME, et al.: Clinical assessment scale for the rating of oral mucosal changes associated with bone marrow transplantation. Development of an oral mucositis index. Cancer 69 (10): 2469-77, 1992

- McGuire DB, Peterson DE, Muller S, et al.: The 20 item oral mucositis index: reliability and validity in bone marrow and stem cell transplant patients. Cancer Invest 20 (7-8): 893-903, 2002

- Maria OM, Eliopoulos N and Muanza T (2017) Radiation-Induced Oral Mucositis. Front. Oncol. 2017, 7:89. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00089 https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fonc.2017.00089/full

- Chen SC, Lai YH, Huang BS, Lin CY, Fan KH, Chang JT. Changes and predictors of radiation-induced oral mucositis in patients with oral cavity cancer during active treatment. Eur J Oncol Nurs (2015) 19(3):214–9. doi:10.1016/j.ejon.2014.12.001

- WCCNR. Assessing stomatitis: refinement of the Western Consortium for Cancer Nursing Research (WCCNR) stomatitis staging system. Can Oncol Nurs J (1998) 4:160–5

- Trotti A, Byhardt R, Stetz J, Gwede C, Corn B, Fu K, et al. Common toxicity criteria: version 2.0. An improved reference for grading the acute effects of cancer treatment: impact on radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys (2000) 47:13–47. doi:10.1016/S0360-3016(99)00559-3

- National Cancer Institute. Common Toxicity Criteria. Version 2.0. (1999). https://ctep.cancer.gov/protocoldevelopment/electronic_applications/docs/ctcv20_4-30-992.pdf

- Keefe DM, Schubert MM, Elting LS, et al.: Updated clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and treatment of mucositis. Cancer 109 (5): 820-31, 2007

- Rosen LS, Abdi E, Davis ID, et al.: Palifermin reduces the incidence of oral mucositis in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer treated with fluorouracil-based chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol 24 (33): 5194-200, 2006

- Vadhan-Raj S, Trent J, Patel S, et al.: Single-dose palifermin prevents severe oral mucositis during multicycle chemotherapy in patients with cancer: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med 153 (6): 358-67, 2010

- Henke M, Alfonsi M, Foa P, et al.: Palifermin decreases severe oral mucositis of patients undergoing postoperative radiochemotherapy for head and neck cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Clin Oncol 29 (20): 2815-20, 2011

- Le QT, Kim HE, Schneider CJ, et al.: Palifermin reduces severe mucositis in definitive chemoradiotherapy of locally advanced head and neck cancer: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Clin Oncol 29 (20): 2808-14, 2011

- Kuhn A, Porto FA, Miraglia P, et al.: Low-level infrared laser therapy in chemotherapy-induced oral mucositis: a randomized placebo-controlled trial in children. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 31 (1): 33-7, 2009

- Bennett LL, Rosenblum RS, Perlov C, et al.: An in vivo comparison of topical agents on wound repair. Plast Reconstr Surg 108 (3): 675-87, 2001

- Schubert MM, Peterson DE: Oral complications of hematopoietic cell transplantation. In: Appelbaum FR, Forman SJ, Negrin RS, et al., eds.: Thomas’ Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation: Stem Cell Transplantation. 4th ed. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009, pp 1589-1607

- Pillitteri LC, Clark RE: Comparison of a patient-controlled analgesia system with continuous infusion for administration of diamorphine for mucositis. Bone Marrow Transplant 22 (5): 495-8, 1998

- Rocke LK, Loprinzi CL, Lee JK, et al.: A randomized clinical trial of two different durations of oral cryotherapy for prevention of 5-fluorouracil-related stomatitis. Cancer 72 (7): 2234-8, 1993

- Ohbayashi Y, Imataki O, Ohnishi H, et al.: Multivariate analysis of factors influencing oral mucositis in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Ann Hematol 87 (10): 837-45, 2008.

- Lugliè PF, Mura G, Mura A, et al.: [Prevention of periodontopathy and oral mucositis during antineoplastic chemotherapy. Clinical study] Minerva Stomatol 51 (6): 231-9, 2002

- Schmidt W, Rainville LC, McEneff G, Sheehan D, Quinn B. A proteomic evaluation of the effects of the pharmaceuticals diclofenac and gemfibrozil on marine mussels (Mytilus spp.): evidence for chronic sublethal effects on stress-response proteins. Drug Test Anal (2014) 6(3):210–9. doi:10.1002/dta.1463