What is pericarditis

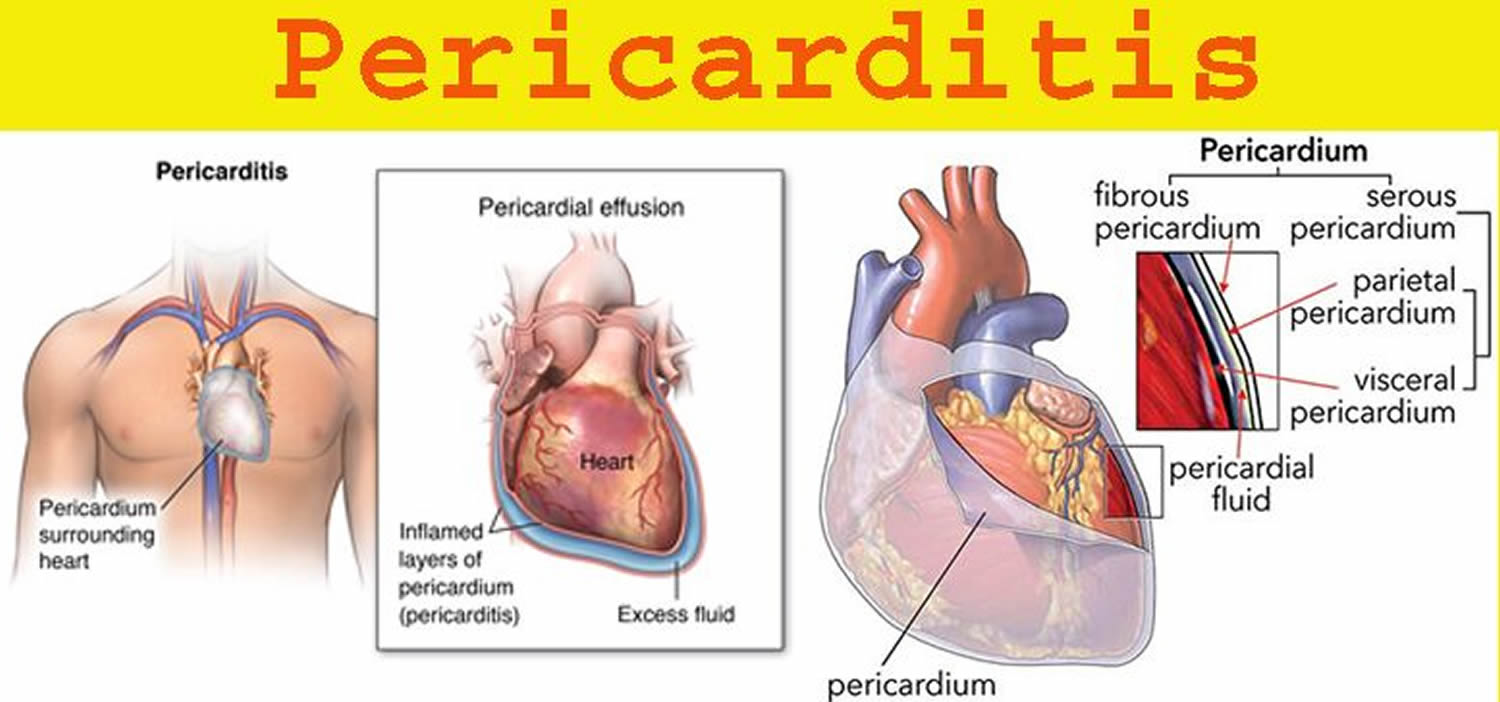

Pericarditis is inflammation of the pericardium, the thin protective sac that surrounds your heart 1. This can affect the pumping function of the heart and lead to heart failure. The pericardium has an inner and outer layer and can become inflamed if blood or fluid leaks between these two layers (see Figures 1 and 2). In pericarditis, the pericardium gets inflamed, and blood or fluid can leak into it. Pericarditis is often associated with pericardial effusion (build-up of fluid within the structures). Pericarditis causes chest pain and a high temperature (fever).

Symptoms of pericarditis include:

- Sharp chest pain that’s similar to a stabbing sensation, which may feel worse when swallowing or piercing chest pain in the center or left side of your chest. However, some people with acute pericarditis describe their chest pain as dull, achy or pressure-like instead, and of varying intensity.

- Pain in the neck that may extend across the shoulders and/or arms

- An intermittent fever

- Nausea

- Light headedness

- In some cases, a sudden onset shortness of breath (if this occurs seek urgent medical attention).

The pain can resolve itself if sitting forward, allowing the heart to relax within the chest cavity.

Usually the cause of pericarditis can’t be found. A viral infection is often suspected, but is difficult to confirm. Pericarditis can also develop after a heart attack. Other less common causes include autoimmune disorders, complication of a bacterial infection, and heart or chest injury.

Pericarditis may also be associated with other pericardial syndromes, such as pericardial effusion, cardiac tamponade, constrictive pericarditis, and effusive-constrictive pericarditis 2.

- Pericarditis is not usually serious, but it can cause complications. Get medical advice if you have chest pain.

Pericarditis is the most common form of pericardial disease worldwide and may recur in as many as one-third of patients who present with idiopathic or viral pericarditis 3.

Most people recover from pericarditis quickly, but for some it can take several months or never fully resolve, making long term sufferers vulnerable to physical and psychological issues. This can impact on quality of life for the sufferer and their families.

Unfortunately, pericarditis can come back despite medical or surgical intervention, so patients may feel uncertain about the future of their health. As this rare condition is not visible or associated with an unhealthy lifestyle, there is often a lack of understanding about the effects of living with pericarditis, meaning sufferers can often feel isolated, causing them to experience other effects such as anxiety, palpitations and panic.

Most people with pericarditis need monitoring and treatment to reduce the pain and swelling.

If complications develop, surgery may be needed.

Seek immediate medical care if you develop new symptoms of chest pain.

Many of the symptoms of pericarditis are similar to those of other heart and lung conditions. The sooner you are evaluated, the sooner you can receive proper diagnosis and treatment. For example, although the cause of acute chest pain may be pericarditis, the original cause could have been a heart attack or a blood clot of the lungs (pulmonary embolus).

The pericardium

The serous membrane is a thin double-layered membrane that covers, lines, partitions, or connects structures. The serous membrane lining the heart cavity and covering the heart is the pericardium. The visceral pericardium covers the surface of the heart; the parietal pericardium lines the chest wall. Between them is the pericardial cavity, filled with a small amount of lubricating serous fluid (contains 15-50 ml of plasma ultrafiltrate) (see Figure 1).

The pericardium confines the heart to its position in the mediastinum, while allowing sufficient freedom of movement for vigorous and rapid contraction. The pericardium consists of two main parts: (1) the fibrous pericardium and (2) the serous pericardium (Figures 1 and 2). The superficial fibrous pericardium is composed of tough, inelastic, dense irregular connective tissue. It resembles a bag that rests on and attaches to the diaphragm; its open end is fused to the connective tissues of the blood vessels entering and leaving the heart. The fibrous pericardium prevents overstretching of the heart, provides protection, and anchors the heart in the mediastinum. The fibrous pericardium near the apex of the heart is partially fused to the central tendon of the diaphragm and therefore movement of the diaphragm, as in deep breathing, facilitates the movement of blood by the heart.

The deeper serous pericardium is a thinner, more delicate membrane that forms a double layer around the heart (Figure 2). The outer parietal layer of the serous pericardium is fused to the fibrous pericardium. The inner visceral layer of the serous pericardium, which is also called the epicardium, is one of the layers of the heart wall and adheres tightly to the surface of the heart. Between the parietal and visceral layers of the serous pericardium is a thin film of lubricating serous fluid. This slippery secretion of the pericardial cells, known as pericardial fluid, reduces friction between the layers of the serous pericardium as the heart moves. The space that contains the few milliliters of pericardial fluid is called the pericardial cavity.

Due to the parietal pericardium’s rich innervation, any inflammatory process mediated by an infectious, autoimmune or traumatic insult can result in severe retrosternal chest pain, as is commonly seen in acute pericarditis 4. This explains why the vast majority of pericarditis presentations (>90%) have chest discomfort 5. In cases of pericardial effusion, the pericardial compliance can increase in response to slowly accumulating fluid, allowing the pericardial sac to dilate over time without compressing the cardiac chambers 6. This means that the rate of fluid accumulation (and resulting pressure changes, as in pericardial compliance) is often more important than the volume in determining the hemodynamic consequences affecting the heart. By this virtue, a relatively small pericardial effusion can cause life-threatening tamponade if it accumulates precipitously, while an incipient process (such as cancer) can allow a large pericardial effusion to form over weeks before exerting constrictive physiology over the cardiac chambers 7.

Figure 1. Pericardium

Figure 2. Pericardium, pericardial cavity and heart wall

Pericarditis types

The main types of pericarditis are 3:

- Acute pericarditis – symptoms begin suddenly and usually lasts less than three weeks.

- Incessant pericarditis lasts about four to six weeks but less than three months and is continuous.

- Chronic pericarditis – symptoms develop gradually and persist, or may persist after an acute attack but last longer than three months.

- Recurring pericarditis – repeated attacks of acute pericarditis with a symptom-free interval in between and it occurs about four to six weeks after an episode of acute pericarditis.

Acute episodes of pericarditis typically last a few weeks, but future episodes can occur. Some people with pericarditis have a recurrence within months after the original episode.

Pericarditis complications

Complications of pericarditis can be:

- Constrictive pericarditis – Although uncommon, some people with pericarditis, particularly those with long-term inflammation and chronic recurrences, can develop permanent thickening, scarring and contraction of the pericardium. In these people, the pericardium loses much of its elasticity and resembles a rigid case that’s tight around the heart, which keeps the heart from working properly. This condition is called constrictive pericarditis and often leads to severe swelling of the legs and abdomen, as well as shortness of breath.

- Cardiac tamponade – a dangerous condition, where too much fluid collects in the pericardium, which puts pressure on the heart and causes blood pressure to drop dramatically. This is life-threatening and requires emergency treatment. Excess fluid puts pressure on the heart and doesn’t allow it to fill properly. That means less blood leaves the heart, which causes a dramatic drop in blood pressure. Cardiac tamponade can be fatal if it isn’t promptly treated.

Frequently, pericarditis can be accompanied by increased fluid accumulation within the pericardial sac forming a pericardial effusion, which may be serous, hemorrhagic or purulent depending on the underlying cause 1. This fluid accumulation may become hemodynamically significant, particularly when the pericardial effusion is large, or rate of accumulation is too rapid, as the fluid can extrinsically compress the cardiac chambers limiting diastolic filling and causing the syndrome of cardiac tamponade 6. This can present with obstructive shock and is considered a medical emergency requiring immediate intervention. Additionally, pericarditis may be followed by pericardial thickening, which can rarely present as constrictive pericarditis months or even years after the initial insult has passed. A more recently described entity called effusive-constrictive pericarditis, occurs when there is fluid accumulation around the heart, but constrictive physiology (such as respiratory enhanced interventricular dependence, restrictive E/A filling pattern, mitral annulus reversus with septal e’ > lateral e’, etc…) is displayed even after pericardiocentesis is performed marking constrictive pathology independent of the presence of a pericardial effusion 2.

Pericarditis causes

Under normal circumstances, the two-layered pericardial sac that surrounds your heart contains a small amount of lubricating fluid. In pericarditis, the sac becomes inflamed and the resulting friction from the inflamed sac leads to chest pain.

The cause of pericarditis is often hard to determine. In most cases, doctors either are unable to determine a cause (idiopathic) or suspect a viral infection.

Pericarditis can also develop shortly after a major heart attack, due to the irritation of the underlying damaged heart muscle. In addition, a delayed form of pericarditis may occur weeks after a heart attack or heart surgery.

This delayed pericarditis is known as Dressler’s syndrome. Dressler’s syndrome may also be called postpericardiotomy syndrome, post-myocardial infarction syndrome and post-cardiac injury syndrome 8.

Pericarditis can be caused by:

- Cardiovascular disorders, such as acute myocardial infarction (heart attack), Dressler syndrome and aortic dissection

- Heart surgery

- Infectious conditions, such as viral (such as the flu), bacterial, HIV/AIDS and tuberculous infections

- Inflammatory disorders, such as rheumatoid arthritis, SLE (Systemic Lupus Erythematosus), scleroderma, and rheumatic fever

- Metabolic disorders, such as renal failure and hypothyroidism

- in rare cases, some form of cancer

- Inflammation of the myocardium (the heart muscle) rubbing against the pericardium

- Miscellaneous causes, such as iatrogenic, neoplasms, drugs, irradiation, sarcoidosis, cardiovascular procedures, and trauma

- Trauma. Injury to your heart or chest may occur as a result of a motor vehicle or other accident

- Certain medications. Some medications can cause pericarditis, although this is unusual.

Sometimes the cause will be unknown (idiopathic). It is estimated that 80-90% of all cases of acute pericarditis are presumed to be idiopathic. Acute idiopathic pericarditis usually affects young and otherwise healthy individuals. Many patients have mild symptoms, don’t seek medical help and the conditions resolve on their own.

What causes pericarditis

Pericarditis is a complex condition with many variations and causes. A patient may need a physical examination and a doctor will consider their medical history in order for them to be diagnosed with the condition.

The 2015 European Society of Cardiology guidelines for the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases divided the cause of acute pericarditis into two main groups, infectious causes, and non-infectious causes 9.

Infectious causes

Viruses are considered the most common infective agents and include coxsackieviruses A and B, echovirus, adenoviruses, parvovirus B19, HIV, influenza as well as multiple herpes viruses such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and cytomegalovirus (CMV) 10. However, testing for specific viruses is not routine practice because determining the virus rarely has an impact on treatment. Furthermore, this process is expensive 11. Bacterial causes of pericarditis occur infrequently in the developed world, however tuberculosis infection is still very prevalent in the developing countries, and is cited as the most common cause of pericarditis in the endemic parts of the world 12. This is especially true in HIV positive patients, where the rate of infection is reported to be increasing 13. Less commonly, other forms of bacteria can cause pericarditis including Coxiella burnetii, Meningococcus, Pneumococcus, Staphylococcus and Streptococcus with cases of life threatening purulent cardiac tamponade reported in the literature 14. In extremely rare cases, pericarditis can be caused by fungal organisms such as Histoplasma, Coccidioides, Candida and Blastomyces or parasitic species such as Echinococcus, and Toxoplasma 15. When such organisms are encountered, an immunocompromised state should be strongly considered as many fungi and parasites such as Histoplasma and Toxoplasma are opportunistic in nature, and have been described predominantly in HIV patients.

Non-infectious causes

Non-infectious causes are numerous and include malignancy (often secondary to metastatic disease), connective tissue disease (such as systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and Behçet’s disease), and metabolic causes (such as uremia, and myxedema) 16.

Trauma may also cause pericarditis with early onset following injury or as more frequently encountered in clinical practice, result in a delayed inflammatory reaction 17. Dressler syndrome, also called “late post-myocardial infarction syndrome”, is a well-recognized post-cardiac injury syndrome where pericarditis is preceded by acute coronary syndrome, with a delayed inflammatory response usually several weeks after the initial event 18. It is believed to occur secondary to formed antimyocardial antibodies as a delayed autoimmune process causing symptoms of pericarditis in the late post-myocardial infarction stage 8. When first described, its incidence was estimated at 5-7% of heart attacks (myocardial infarctions), but it has become an uncommon entity with the many improvements achieved in the management of acute coronary syndrome, resulting in early revascularization, and reduced burden of myocardial injury. Other post-cardiac injury syndromes can also occur following percutaneous intervention, cardiac surgery or blunt trauma 19.

Multiple medications have been implicated in drug-induced pericarditis, with a long list of possible culprits, but the incidence remains rare. Certain medications, such as procainamide, hydralazine, and isoniazid were historically cited to cause medication-induced systemic lupus erythematosis (SLE), with associated serositis and pericardial involvement manifesting as pericarditis 20. More recently, checkpoint inhibitor, such as ipilimumab and nivolumab, have emerged as an increasingly recognized cause of cardiac toxicity, including myocarditis and pericarditis. The two most prominent classes are monoclonal antibodies to cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 (CTLA- 4), and programmed cell death 1 (PD-1) and its ligand PD-L1, which have had numerous progressive applications in the field of oncology, and are expected to be implicated in more cases as their clinical use increases 21.

Miscellaneous disease processes such as amyloidosis, and sarcoidosis should also be considered, especially when pericarditis occurs in association with suggestive systemic findings 22. However, in up to 90% of cases, no clear cause can be established and a diagnosis of idiopathic acute pericarditis is made. This is the most common form encountered in clinical practice, and an exhaustive panel of testing is seldom necessary in the absence of directed clinical suspicion.

Pericarditis symptoms

If you have acute pericarditis, the most common symptom of pericarditis is sharp, piercing or stabbing chest pain in the center or left side of your chest. However, some people with acute pericarditis describe their chest pain as dull, achy or pressure-like instead, and of varying intensity. An early set of symptoms such as fever (usually <102.2°F [39°C]), malaise and muscle ache (myalgia) and/or joint pain (arthralgia) is common.

The pain of acute pericarditis may travel into your left shoulder and neck. It often intensifies when you cough, lie down or inhale deeply. Sitting up and leaning forward can often ease the pain. At times, it may be difficult to distinguish pericardial pain from the pain that occurs with a heart attack. As in heart attack, chest pain can radiate to the neck, arms, or left shoulder; however, if pain radiates to one or both trapezius muscle ridges it is likely due to pericarditis because the phrenic nerve that innervates these muscles traverses the pericardium.

Depending on the cause of pericarditis, symptoms may also include some or all of the following:

- Sharp, piercing chest pain over the center or left side of the chest, which is generally more intense when breathing in

- Shortness of breath when reclining

- Heart palpitations

- Low-grade fever

- An overall sense of weakness, fatigue or feeling sick

- Cough

- Abdominal or leg swelling

- Nausea

- Dry cough

Chronic pericarditis is usually associated with chronic inflammation and may result in fluid around the heart (pericardial effusion). The most common symptom of chronic pericarditis is chest pain.

Pericarditis diagnosis

Your doctor likely will start by taking your medical history and asking questions about your chest pain and other symptoms. As part of your initial evaluation, your doctor will also perform a physical exam and check your heart sounds.

While listening to your heart, your doctor will place a stethoscope on your chest to check for the sounds characteristic of pericarditis, which are made when the pericardial layers rub against each other. This characteristic noise is called a pericardial rub. The audible friction rub, which is highly specific for pericarditis, is present in 85% of patients at some time during the course of the disease. It is usually a high-pitched, scratchy or squeaky sound best heard at the left sternal border and consisting of 3 phases that correspond to the movement of the heart during 3 phases of the cardiac cycle: 1) atrial systole, 2) ventricular systole, and 3) rapid ventricular filling during early diastole 11. However, some rubs are present in only one (monophasic) or two (biphasic) components of the cardiac cycle 16.

All patients suspected to have acute pericarditis should initially undergo an ECG, echocardiogram, and chest X-ray.

Your doctor may have you undergo tests that can help determine whether you’ve had a heart attack, whether fluid has collected in the pericardial sac or whether there are signs of inflammation. Your doctor may use blood tests to determine if a bacterial or other type of infection is present.

Tests for pericarditis include:

- Electrocardiogram (ECG). In this test, patches with wires (electrodes) are attached to your skin to measure the electrical impulses given off by your heart. Impulses are recorded as waves displayed on a monitor or printed on paper. Certain ECG results may indicate pericarditis, while others could indicate a heart attack.

- Chest X-ray. With an X-ray of your chest, your doctor can study the size and shape of your heart. Images of your heart may show an enlarged heart if excess fluid has accumulated in the pericardium.

- Echocardiogram. This test uses high-frequency sound waves to create an image of your heart and its structures, including fluid accumulation in the pericardium. Your doctor can view and analyze this image on a monitor.

- Computerized tomography (CT). This X-ray technique can produce more-detailed images of your heart and the pericardium than can conventional X-ray studies. CT scanning may be done to exclude other causes of acute chest pain, such as a blood clot in a lung artery (pulmonary embolus) or a tear in your aorta (aortic dissection). CT scanning can also be used to look for thickening of the pericardium that might indicate constrictive pericarditis.

- Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). This technique uses a magnetic field and radio waves to create cross-sectional images of your heart that can reveal thickening, inflammation or other changes in the pericardium.

The electrocardiogram (ECG) is the most important tool in the diagnosis of pericarditis 11. It may show sinus tachycardia and widespread ST-segment elevation which has been considered the hallmark of acute pericarditis. Nevertheless the pericardium is electrically silent. Indeed, the ST-elevation is the expression of subepicardial myocardial involvement and has been reported in 60% to 90% of consecutive cases of acute pericarditis, while troponin elevation has been reported in a higher number of cases yet (90–98%). Thus, mixed myocardial and pericardial involvement is probably present in the majority of cases 23.

The ST segment is usually coved (concave) upward and resembles the current of injury of acute transmural ischemia. The distinction between acute pericarditis and ischemia is not usually difficult because lead involvement is more extensive in pericarditis and prominent reciprocal ST-segment depression in ischemia, which usually is absent in pericarditis, shows. Another recent criteria to differentiate acute ST elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) from acute pericarditis may improve the differential diagnostic yield of the classical ECG criteria; it is the prolongation of the QRS complex and shortening of the QT interval in ECG leads with ST segment elevation which are not the case in patients with pericarditis 23.

PR-depression is another feature in the ECG of the patient with pericarditis. According to a study by Porela et al 24 the most common location for PR depression was lead II (55.9%), while this ECG finding least likely appeared in lead aVL (2.9%). PR depression in any lead had a high sensitivity (88.2%), but fairly low specificity (78.3%) for myopericarditis. The combination of PR depressions in both precordial and limb leads had the most favourable predictive power to differentiate myopericarditis from STEMI (positive 96.7% and negative power 90%) 24.

Myocardial inflammatory and injury markers such as ESR, CRP and troponins should also be obtained 25. In the developed world where tuberculosis infection is not suspected, this work up may be adequate and further diagnostic testing is not required as most cases respond promptly to empiric treatment 26. If a specific cause is suspected then further testing may be warranted, and would be tailored towards that specific cause.

First level tests such as a complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, liver function tests, and thyroid stimulation hormone level are recommended if further work up is pursued and may be suggestive of a particular cause such as uremia or infection. In select patients, blood cultures, viral seromarkers and tuberculosis testing [such as purified protein derivative test (also known as PPD skin test or tuberculosis skin test) or quantiferon TB essays] may be performed as well. HIV testing with antibody/antigen testing or nucleic acid testing (NAT) should be obtained if patients are found to have an opportunistic infection, since a strong correlation exists between an immunocompromised state, and fungal or tuberculosis infection 26. Further work up may include obtaining anti-nuclear antibody (ANA) serologies, or pursuing targeted testing towards a suspected systemic disease such as sarcoidosis.

The European Society of Cardiology 2015 guidelines require 2 out of 4 criteria to be me in order to diagnose acute pericarditis 10. They include (1) pericardial chest pain, (2) pericardial rubs, (3) new widespread ST-elevation or PR depression on ECG, and (4) pericardial effusion (new or worsening). Supporting findings also include elevated inflammatory biomarkers (ESR, CRP, leukocytosis), and evidence of pericardial inflammation on advanced imaging, such as cardiac computed tomography (CT) and cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR). Pericardial effusion, though often present, is not required to make a definitive diagnosis of acute pericarditis 23.

The European Society of Cardiology 2015 guidelines support obtaining a computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) as a Class I recommendations when second-line testing is pursued 27. Cardiac CT may show thickened pericardial layers, with pericardial fluid accumulation, and calcification can be prominent with constrictive pericarditis. However, it cannot be used to assess parameters of hemodynamic compromise in cardiac tamponade similar to echocardiography, and is associated with increased radiation risk. Cardiac MRI can show more detailed information including late gadolinium enhancement within the pericardial layers, or even within the myocardium if myopericarditis is present. It may also show intra-myocardial strands if a fibrinous pericardial effusion is present, and is excellent for the assessment of myocardial function or any suspicious pericardial masses 28.

Emergent pericardiocentesis is recommended in patient presenting with cardiac tamponade 29. Pericardiocentesis may also be performed less urgently in the presence of moderate to large pericardial effusion without immediate hemodynamic compromise, and a chest tube can be left in place for several days or until drainage desists. Diagnostic pericardiocentesis may also be performed if an infectious cause of acute pericarditis is suspected even if the effusion size is small. Bacterial, fungal and tuberculosis pericardial fluid studies including basic chemistry, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and fluid cultures should be performed, ands blood cultures should be obtained where appropriate 29. Purulent effusions, though rare, are associated with high mortality. They should be treated aggressively with urgent drainage followed by the use of intra-pericardial thrombolysis in cases of loculated effusions. The aspirate may be frankly purulent, and the presence of low pericardial:serum glucose ratio < 0.3, and neutrophilic predominance (mean cell count 2.8/μl, 92% neutrophils) differentiates it from mycobacterial or neoplastic pericarditis 30.

An exudative pericardial effusion warrants empiric anti-tuberculosis treatment in parts of the world where tuberculosis is endemic, even while cultures are still pending. If a positive diagnosis of tuberculosis is confirmed, then medical therapy with at least 6 months is recommended and pericardiectomy should be consider if there is failure of improvement on therapy within 4-8 weeks 31. Pericardial thickening is present is most cases of tuberculosis pericarditis, and before effective medical therapy was available effusive pericarditis would progress to constrictive pericarditis in up to half of all cases. Studies have showed that the addition of high-dose adjunctive prednisolone can reduce the incidence of constrictive pericarditis, but may increase the risk HIV-associated malignancies 32. Consequently, the addition of adjunctive steroids may be considered in HIV-negative patients, but should be avoided in HIV-positive patients per ESC guidelines 30.

Pericardial fluid analysis with cytology is recommended for the confirmation of malignant pericardial disease. Further testing may include pericardial biopsy and tumor marker testing such as carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) and CA-19, although evidence for their accuracy in distinguishing malignant effusions is limited 33. If a definite viral pericarditis diagnosis is pursued, then a comprehensive histological, cytological and molecular analysis should be performed on obtained pericardial fluid and any pericardial biopsy. However, routine viral serological testing is not recommended except for HIV and hepatitis C virus (HCV) 30.

The incidence of uremic pericarditis has seen significant decline with the introduction of dialysis 34. The presentation with pleuritic chest pain is also less prevalent in this subpopulation, with absent ECG changes in most. Chronically, these patients are more likely to develop pericardial effusions, but they are not frequently associated with acute cardiac tamponade. However, if pericardiocentesis is performed, then aspirate is often bloody in this patient population 35.

Cardiac catheterization may be considered to assess for diastolic pressure equalization, and respiratory interventricular dependence if constrictive pericarditis is suspected, but is not recommended diagnostically for patients with acute pericarditis only 35.

Pericarditis treatment

Treatment will depend on type, the cause as well as the severity of pericarditis you have. Mild cases of pericarditis may get better on their own without treatment.

Pericarditis treatment may include:

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as Ibuprofen to reduce swelling. You should feel better within 1 to 2 weeks.

- Antibiotics. When a bacterial infection is the underlying cause of pericarditis, you’ll be treated with antibiotics and drainage if necessary.

- Colchicine (Colcrys, Mitigare). This drug, which reduces inflammation in the body, may be prescribed for acute pericarditis or as a treatment for recurrent symptoms. Colchicine can reduce the length of pericarditis symptoms and decrease the risk that the condition will recur. However, the drug is not safe for people with certain pre-existing health problems, such as liver or kidney disease, and for those taking certain medications. Your doctor will carefully check your health history before prescribing colchicine.

- Pain killers. Most pain associated with pericarditis responds well to treatment with pain relievers available without a prescription, such as aspirin or ibuprofen (Advil, Motrin IB, others). These medications also help lessen inflammation. Prescription-strength pain relievers also may be used.

- Corticosteroids. If you don’t respond to pain killers or colchicine or if you have recurrent symptoms of pericarditis, your doctor may prescribe a steroid medication, such as prednisone.

- If symptoms don’t resolve surgery may be necessary – pericardial window (a procedure to drain the sac surrounding the heart) is normally performed to treat and permanently prevent symptoms from persisting or coming back.

If an underlying cause is found, it will be treated where possible. You may also be monitored for potential complications.

For most mild cases of pericarditis, rest and over-the-counter pain medications — taken under your doctor’s direction — may be all that’s needed. While you recuperate, avoid rigorous physical activity. Strenuous activity can trigger pericarditis symptoms 36. Ask your doctor how long you need to take it easy.

In the majority of patients, empiric treatment with high dose anti-inflammatory agents in addition to colchicine is recommended, and NSAID therapy should continue until symptom relief. This period is typically between 3 days to 2 weeks. Possible regimens include Ibuprofen 600mg every 8 hours, indomethacin 25-50mg every 8 hours, or naproxen 500-1000mg every 12 hours 37. Aspirin 100mg every 6 – 8 hours should be substituted for other NSAIDs in post-myocardial infarction, or for patients already on anti-platelet therapy. It is also first line therapy in the first term of pregnancy, but contraindicated past 20 weeks of gestation where paracetamol may be used.

The COlchicine for acute PEricarditis (COPE) trial randomized 120 patients to conventional therapy with aspirin, versus conventional therapy with adjunctive colchicine and followed them over a period of 18 months. The latter group demonstrated less symptom persistence at 72 hours (11.7% versus 36.7%) and significantly less recurrent episodes (10.7% versus 32.3%) as compared to the control group 38. Several studies also showed benefit when colchicine is used in the treatment of recurrent pericarditis, decreasing further recurrences in half 39. Consequently, adjunctive colchicine therapy is now recommended in most patients with acute pericarditis for a period of 3-6 months. The recommended dose is 0.6mg orally twice daily for weight > 70 kg, and 0.5mg orally once daily for weight < 70 kg. Colchicine is contraindicated in patient with severe renal impairment and in pregnant and lactating women.

Low to moderate doses (i.e. prednisone 0.2–0.5 mg/kg/day or equivalent) with slow taper may also be used if a regimen of NSAIDS/aspirin and colchicine is contraindicated. While the latter often offers rapid clinical improvement, there is ample evidence that steroid use increases the risk for recurrent pericarditis after discontinuation of therapy 40. Consequently, corticosteroids are not recommended as first-line therapy in most patients unless an autoimmune etiology for acute pericarditis is identified. The initial dose should be maintained until symptoms relief and CRP normalization, then tapered down slowly 40.

Response to therapy is assessed clinically based on symptom relief, but serial CRP measurements can be helpful as well. If there is an incomplete response to anti-inflammatory agents (aspirin or NSAIDs) with adjunctive colchicine (such as recurrent pericarditis), then the addition of steroids as triple therapy should be considered after an infectious etiology is ruled out 41.

For corticosteroid-dependent recurrent pericarditis, steroid-sparing immunosuppressive agents such as azathioprine, IVIG or anakinra (an IL-1 receptor antagonist) may be used as third line therapy 42. If all else fails, pericardiectomy remains a last resort 43.

Patients with uremic pericarditis should undergo more frequent dialysis, while patients with malignancy and tuberculosis should receive therapy directed at the primary disease process. For tuberculosis, standard therapy is with quadruple antibiotics (rifampicin, isoniazid, pyrazinamide and ethambutol) for at least 2 months followed by isoniazid and rifampicin for a total of 6 months, with or without adjunctive high-dose prednisolone as discussed above 31.

Patients who have markers of poor prognosis or who do not respond to therapy within 1 week should be admitted and investigated further. These markers include fever ( > 100.4°F [38°C]), subacute or recurrent presentation, the presence of a large pericardial effusion (>20mm in thickness), or cardiac tamponade physiology on echocardiogram (such as right ventricular diastolic collapse, transmitral flow respirophasic variation more the 25% throughout the respiratory cycle, and a dilated inferior vena cava with inspiratory collapse < 50% indicating elevated right atrial filling pressures) 44. Minor markers of risk include immunosuppression, trauma or myopericarditis where patients have troponin elevation associated with elevated inflammatory markers.

Hospitalization and procedures

You’ll likely need hospitalization if your doctor suspects cardiac tamponade, a dangerous complication of pericarditis due to fluid buildup around the heart.

If cardiac tamponade is present, your doctor may recommend a procedure to relieve fluid buildup, such as:

- Pericardiocentesis. In this procedure, a doctor uses a sterile needle or a small tube (catheter) to remove and drain the excess fluid from the pericardial cavity. You’ll receive a local anesthetic before undergoing pericardiocentesis, which is often done with echocardiogram monitoring and ultrasound guidance. This drainage may continue for several days during the course of your hospitalization.

- Pericardiectomy. If you’re diagnosed with constrictive pericarditis, you may need to undergo a surgical procedure (pericardiectomy) to remove the entire pericardium that has become rigid and is making it hard for your heart to pump.

Coping and support for pericarditis

Living with pericarditis can be emotionally challenging for you and your family. It is important to manage anxiety and stress and there are many outlets of support to help you. Talk to your doctor about being referred for counseling or Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT).

Recovery from pericarditis

Most people recover from pericarditis quickly, but for some it can take several months or have longer effects.

As pericarditis is a rare condition that can’t be seen or linked with an unhealthy lifestyle, it can be challenging to understand the effects of living with pericarditis. Because of this people with pericarditis may often feel isolated, causing them to experience other effects such as anxiety, palpitations and panic attacks.

Pericarditis prognosis

The overall prognosis of acute pericarditis is excellent with most patients experiencing a complete recovery 1. Recurrent pericarditis can occur in up to 30% of patients not treated with colchicine as per current date, and constrictive pericarditis is exceedingly rare following idiopathic acute pericarditis, occurring in <1% of cases. However, the risk of constriction increases with specific etiologies, especially purulent bacterial or tuberculosis pericarditis, and maybe as high as 30% 45. Cardiac tamponade as the most feared acute complication rarely occurs following idiopathic pericarditis but is more frequently encountered in association with malignancy and infectious causes of pericarditis 46.

References- Dababneh E, Siddique MS. Pericarditis. [Updated 2020 Aug 10]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2021 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK431080

- Maisch B. Management von Perikarditis und Perikarderguss, konstriktiver und effusiv-konstriktiver Perikarditis [Management of pericarditis and pericardial effusion, constrictive and effusive-constrictive pericarditis]. Herz. 2018 Nov;43(7):663-678. German. doi: 10.1007/s00059-018-4744-9

- Imazio M, Gaita F, LeWinter M. Evaluation and Treatment of Pericarditis: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2015;314(14):1498–1506. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.12763

- Hoit BD. Anatomy and Physiology of the Pericardium. Cardiol Clin. 2017 Nov;35(4):481-490. doi: 10.1016/j.ccl.2017.07.002

- Imazio M, Gaita F, LeWinter M. Evaluation and Treatment of Pericarditis: A Systematic Review. JAMA. 2015 Oct 13;314(14):1498-506. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.12763. Erratum in: JAMA. 2015 Nov 10;314(18):1978. Erratum in: JAMA. 2016 Jan 5;315(1):90. Dosage error in article text.

- Little WC, Freeman GL. Pericardial disease. Circulation. 2006 Mar 28;113(12):1622-32. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.561514. Erratum in: Circulation. 2007 Apr 17;115(15):e406. Dosage error in article text.

- Ben-Horin S, Bank I, Guetta V, Livneh A. Large symptomatic pericardial effusion as the presentation of unrecognized cancer: a study in 173 consecutive patients undergoing pericardiocentesis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2006 Jan;85(1):49-53. doi: 10.1097/01.md.0000199556.69588.8e. Erratum in: Medicine (Baltimore). 2006 May;85(3):191.

- Wessman DE, Stafford CM. The postcardiac injury syndrome: case report and review of the literature. South Med J. 2006 Mar;99(3):309-14. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000203330.15503.0b

- Adler Y, Charron P. The 2015 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2873-4. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv47

- Adler Y, Charron P. The 2015 ESC Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Eur Heart J. 2015 Nov 7;36(42):2873-4. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv479

- Acute Pericarditis. An article from the e-journal of the ESC Council for Cardiology Practice Vol. 12, Number 16; 19 Feb 2014. https://www.escardio.org/Journals/E-Journal-of-Cardiology-Practice/Volume-12/Acute-Pericarditis

- Mayosi BM, Burgess LJ, Doubell AF. Tuberculous pericarditis. Circulation. 2005 Dec 6;112(23):3608-16. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.543066

- Ntsekhe M, Mayosi BM. Tuberculous pericarditis with and without HIV. Heart Fail Rev. 2013 May;18(3):367-73. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9310-6

- Petcu, C. P., Dilof, R., Bătăiosu, C., & Petcu, P. D. (2013). Purulent pericardial effusions with pericardial tamponade – diagnosis and treatment issues. Current health sciences journal, 39(1), 53–56. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3945255

- Oladele, R. O., Ayanlowo, O. O., Richardson, M. D., & Denning, D. W. (2018). Histoplasmosis in Africa: An emerging or a neglected disease?. PLoS neglected tropical diseases, 12(1), e0006046. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pntd.0006046

- Khandaker, M. H., Espinosa, R. E., Nishimura, R. A., Sinak, L. J., Hayes, S. N., Melduni, R. M., & Oh, J. K. (2010). Pericardial disease: diagnosis and management. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 85(6), 572–593. https://doi.org/10.4065/mcp.2010.0046

- Imazio M, Negro A, Belli R, Beqaraj F, Forno D, Giammaria M, Trinchero R, Adler Y, Spodick D. Frequency and prognostic significance of pericarditis following acute myocardial infarction treated by primary percutaneous coronary intervention. Am J Cardiol. 2009 Jun 1;103(11):1525-9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.01.366

- Imazio M, Lazaros G, Brucato A, Gaita F. Recurrent pericarditis: new and emerging therapeutic options. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2016 Feb;13(2):99-105. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2015.115

- Jaworska-Wilczynska M, Abramczuk E, Hryniewiecki T. Postcardiac injury syndrome. Med Sci Monit. 2011 Nov;17(11):CQ13-14. doi: 10.12659/msm.882029

- Katz U, Zandman-Goddard G. Drug-induced lupus: an update. Autoimmun Rev. 2010 Nov;10(1):46-50. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.07.005

- Altan, M., Toki, M. I., Gettinger, S. N., Carvajal-Hausdorf, D. E., Zugazagoitia, J., Sinard, J. H., Herbst, R. S., & Rimm, D. L. (2019). Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor-Associated Pericarditis. Journal of thoracic oncology : official publication of the International Association for the Study of Lung Cancer, 14(6), 1102–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jtho.2019.02.026

- Wyplosz B, Marijon E, Dougados J, Pouchot J. Sarcoidosis: an unusual cause of acute pericarditis. Acta Cardiol. 2010 Feb;65(1):83-4. doi: 10.2143/AC.65.1.2045894

- Rossello X, Wiegerinck RF, Alguersuari J, Bardají A, Worner F, Sutil M, Ferrero A, Cinca J. New electrocardiographic criteria to differentiate acute pericarditis and myocardial infarction. Am J Med. 2014 Mar;127(3):233-9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.11.006

- Porela, P., Kytö, V., Nikus, K., Eskola, M., & Airaksinen, K. E. (2012). PR depression is useful in the differential diagnosis of myopericarditis and ST elevation myocardial infarction. Annals of noninvasive electrocardiology : the official journal of the International Society for Holter and Noninvasive Electrocardiology, Inc, 17(2), 141–145. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-474X.2012.00489.x

- Klein AL, Abbara S, Agler DA, Appleton CP, Asher CR, Hoit B, Hung J, Garcia MJ, Kronzon I, Oh JK, Rodriguez ER, Schaff HV, Schoenhagen P, Tan CD, White RD. American Society of Echocardiography clinical recommendations for multimodality cardiovascular imaging of patients with pericardial disease: endorsed by the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance and Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2013 Sep;26(9):965-1012.e15. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2013.06.023

- Imazio M, Spodick DH, Brucato A, Trinchero R, Adler Y. Controversial issues in the management of pericardial diseases. Circulation. 2010 Feb 23;121(7):916-28. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.844753

- Cosyns B, Plein S, Nihoyanopoulos P, Smiseth O, Achenbach S, Andrade MJ, Pepi M, Ristic A, Imazio M, Paelinck B, Lancellotti P; European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI); European Society of Cardiology Working Group (ESC WG) on Myocardial and Pericardial diseases. European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging (EACVI) position paper: Multimodality imaging in pericardial disease. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2015 Jan;16(1):12-31. doi: 10.1093/ehjci/jeu128

- Bogaert, J., & Francone, M. (2009). Cardiovascular magnetic resonance in pericardial diseases. Journal of cardiovascular magnetic resonance : official journal of the Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, 11(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1532-429X-11-14

- Maisch B, Seferović PM, Ristić AD, Erbel R, Rienmüller R, Adler Y, Tomkowski WZ, Thiene G, Yacoub MH; Grupo de Trabajo para el Diagnóstico y Tratamiento de las Enfermedades del Pericardio de la Sociedad Europea de Cardiología. Guía de Práctica Clínica para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de las enfermedades del pericardio. Versión resumida [Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases. Executive summary]. Rev Esp Cardiol. 2004 Nov;57(11):1090-114. Spanish. doi: 10.1016/s0300-8932(04)77245-0

- Ben-Horin S, Bank I, Shinfeld A, Kachel E, Guetta V, Livneh A. Diagnostic value of the biochemical composition of pericardial effusions in patients undergoing pericardiocentesis. Am J Cardiol. 2007 May 1;99(9):1294-7. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2006.12.048

- Mayosi BM, Ntsekhe M, Volmink JA, Commerford PJ. Interventions for treating tuberculous pericarditis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(4):CD000526. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000526. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Sep 13;9:CD000526

- Mayosi, B. M., Ntsekhe, M., Bosch, J., Pandie, S., Jung, H., Gumedze, F., Pogue, J., Thabane, L., Smieja, M., Francis, V., Joldersma, L., Thomas, K. M., Thomas, B., Awotedu, A. A., Magula, N. P., Naidoo, D. P., Damasceno, A., Chitsa Banda, A., Brown, B., Manga, P., … IMPI Trial Investigators (2014). Prednisolone and Mycobacterium indicus pranii in tuberculous pericarditis. The New England journal of medicine, 371(12), 1121–1130. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa1407380

- Karatolios K, Pankuweit S, Maisch B. Diagnostic value of biochemical biomarkers in malignant and non-malignant pericardial effusion. Heart Fail Rev. 2013 May;18(3):337-44. doi: 10.1007/s10741-012-9327-x

- Alpert MA, Ravenscraft MD. Pericardial involvement in end-stage renal disease. Am J Med Sci. 2003 Apr;325(4):228-36. doi: 10.1097/00000441-200304000-00009

- Wood JE, Mahnensmith RL. Pericarditis associated with renal failure: evolution and management. Semin Dial. 2001 Jan-Feb;14(1):61-6. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-139x.2001.00017.x

- Seidenberg PH, Haynes J. Pericarditis: diagnosis, management, and return to play. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2006 Apr;5(2):74-9. doi: 10.1007/s11932-006-0034-z

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Trinchero R, Spodick D, Adler Y. Individualized therapy for pericarditis. Expert Rev Cardiovasc Ther. 2009 Aug;7(8):965-75. doi: 10.1586/erc.09.82

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, Demarie D, Demichelis B, Pomari F, Moratti M, Gaschino G, Giammaria M, Ghisio A, Belli R, Trinchero R. Colchicine in addition to conventional therapy for acute pericarditis: results of the COlchicine for acute PEricarditis (COPE) trial. Circulation. 2005 Sep 27;112(13):2012-6. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.542738

- Imazio M, Bobbio M, Cecchi E, Demarie D, Pomari F, Moratti M, Ghisio A, Belli R, Trinchero R. Colchicine as first-choice therapy for recurrent pericarditis: results of the CORE (COlchicine for REcurrent pericarditis) trial. Arch Intern Med. 2005 Sep 26;165(17):1987-91. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.17.1987

- Lotrionte M, Biondi-Zoccai G, Imazio M, Castagno D, Moretti C, Abbate A, Agostoni P, Brucato AL, Di Pasquale P, Raatikka M, Sangiorgi G, Laudito A, Sheiban I, Gaita F. International collaborative systematic review of controlled clinical trials on pharmacologic treatments for acute pericarditis and its recurrences. Am Heart J. 2010 Oct;160(4):662-70. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2010.06.015

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Cumetti D, Brambilla G, Demichelis B, Ferro S, Maestroni S, Cecchi E, Belli R, Palmieri G, Trinchero R. Corticosteroids for recurrent pericarditis: high versus low doses: a nonrandomized observation. Circulation. 2008 Aug 5;118(6):667-71. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.761064

- Finetti M, Insalaco A, Cantarini L, Meini A, Breda L, Alessio M, D’Alessandro M, Picco P, Martini A, Gattorno M. Long-term efficacy of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (anakinra) in corticosteroid-dependent and colchicine-resistant recurrent pericarditis. J Pediatr. 2014 Jun;164(6):1425-31.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.01.065

- Khandaker, M. H., Schaff, H. V., Greason, K. L., Anavekar, N. S., Espinosa, R. E., Hayes, S. N., Nishimura, R. A., & Oh, J. K. (2012). Pericardiectomy vs medical management in patients with relapsing pericarditis. Mayo Clinic proceedings, 87(11), 1062–1070. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.05.024

- Imazio M, Cecchi E, Demichelis B, Ierna S, Demarie D, Ghisio A, Pomari F, Coda L, Belli R, Trinchero R. Indicators of poor prognosis of acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2007 May 29;115(21):2739-44. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.662114

- Imazio M, Brucato A, Maestroni S, Cumetti D, Belli R, Trinchero R, Adler Y. Risk of constrictive pericarditis after acute pericarditis. Circulation. 2011 Sep 13;124(11):1270-5. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.018580

- Kabukcu, M., Demircioglu, F., Yanik, E., Basarici, I., & Ersel, F. (2004). Pericardial tamponade and large pericardial effusions: causal factors and efficacy of percutaneous catheter drainage in 50 patients. Texas Heart Institute journal, 31(4), 398–403. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC548241