Perineural invasion

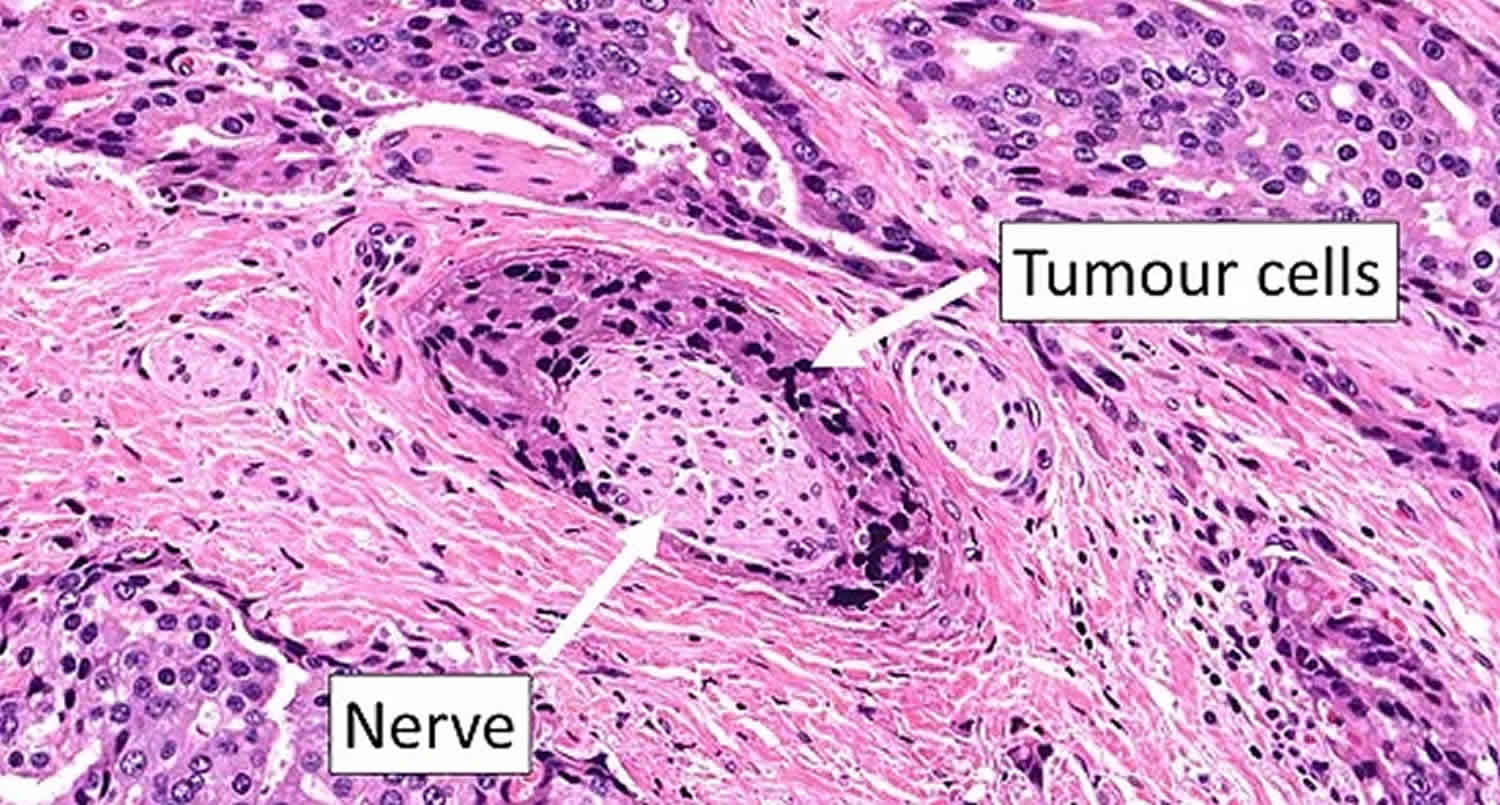

Perineural invasion (PNI) also called neurotropic carcinomatous spread or perineural spread, is cancer cell invasion in, around and through nerves or the finding of tumor cells within any of the the layers (epineurium, perineurium, endoneurium) of the nerve sheath 1. Perineural invasion is believed to promote tumor progression by providing a conduit for cancer cell spread. Patients who experience perineural invasion, which has been described in many cancer types, often have poor prognoses, higher risk of local recurrence, and often suffer from severe pain 2. Perineural invasion is a well-recognized phenomenon in head and neck cancers 3, prostate cancer 4 and colorectal cancer. Perineural invasion in prostate cancer is somewhat helpful in predicting extracapsular tumor extension and may be associated with slightly higher tumor aggressiveness, but studies are conflicting on its clinical usefulness 5.

An important distinction has to be made between perineural invasion (PNI) and perineural spread (PNS). Perineural invasion (PNI) is a histological finding of tumor cell infiltration or associated with small nerves that cannot be radiologically imaged, while perineural spread (PNS) is macroscopic tumor involvement along a nerve extending away from the primary tumor; this can be radiologically apparent. A third term, neurotropism, simply means that a tumor has an affinity for growth along nerves.

There are three layers of connective tissue covering each nerve, namely the outermost epineurium, the middle perineurium, and the innermost endoneurium 6. The inside part of the nerve is separated from the surrounding tumor by multiple layers of collagen and basement membrane. This anatomical structure serves as a low-resistance plane that provides channels to the tumor cells for spreading along the neural sheaths. Once the tumor cells have invaded the nerve sheath, it may access the growth environment that is beneficial for metastasis 7. This was the predominant theory for the last 40 years. Through continuous pathological section analysis, it was found that the transfer mode of perineural invasion was continuous, non-jumping, and direct spreading 7. Thus, tumor cells migrate through a “neural road”.

The patterns of perineural invasion widely varies, including complete and incomplete encirclement, concentric lamination, and tangential contact 8. A more common exist in perineural invasion is tumor cells free inside of the nerve sheath but tumor-nerve contact within the perineurium 9. The current pathological diagnostic criteria of perineural invasion is “tumor in close proximity to nerve and involving at least 33% of its circumference or tumor cells within any of the 3 layers of the nerve sheath” 9, to differentiate this from focal abutment of tumor in the proximity of a nerve 1. In fact, there is no agreement regarding the interpretation of perineural invasion among pathologists who conduct microscopic examination of tissue specimens 10. Thus, the conventional H & E stained section and immunohistochemical examination of biomarkers of autonomic nerves and cancer cells will be necessary. Furthermore, it is necessary to establish a risk model exploring the relationship between nerve-tumor distance and nerve diameter with clinical outcomes 11.

Perineural tumor spread is more frequently associated with 12:

- Mucosal/cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma

- oral cavity/laryngeal (2-30%) > cutaneous (3-8%)

- most common overall 12

- Salivary gland carcinoma

- adenoid cystic carcinoma (highest incidence per individual tumor) 12

- mucoepidermoid carcinoma

- Mucosal/cutaneous basal cell carcinoma (2-5% demonstrate perineural tumor spread) 13

- Melanoma

- Lymphoma

- Sarcoma

- Meningioma (rare) 14

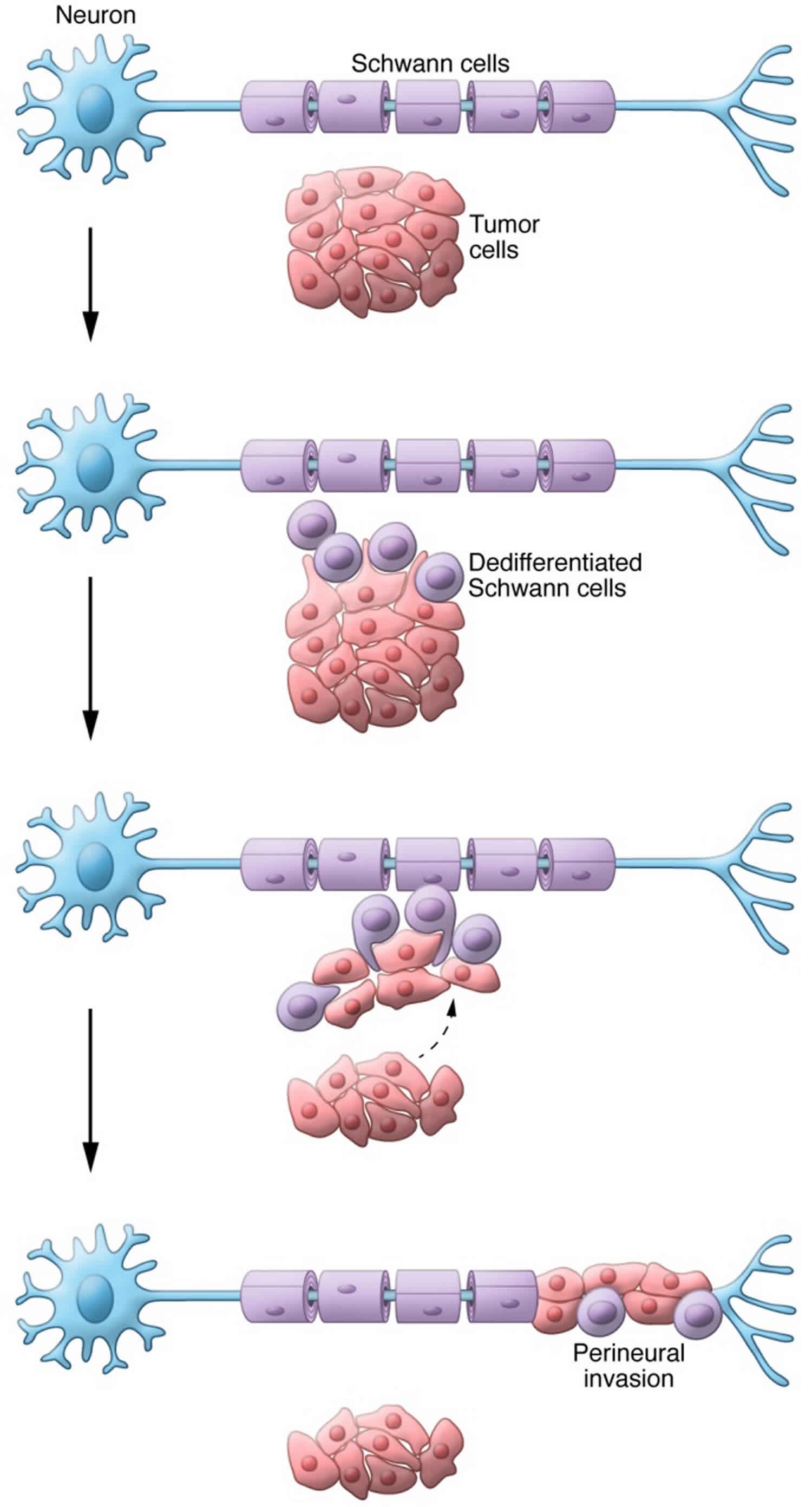

The biologic mechanism of perineural invasion pathogenesis is not well understood, but a recent theory is that it relates to reciprocal signaling interactions and the (acquired) capacity of tumor cells to respond to signals within the peripheral nerve, which promote invasion. A number of neurotrophic agents have been identified as being of possible importance in perineural invasion in other malignancies (prostate, pancreas) 1. Some of these such as NGF and other factors, such as neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM), have been shown to have increased expression in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma demonstrating perineural invasion, and may also have a role in its pathogenesis 15).

Figure 1. Perineural invasion

Footnote: Schwann cells mediate perineural invasion. Dedifferentiated Schwann cells come into direct contact with cancer cells. This direct contact results in the extension of protrusions from the cancer cells. Schwann cells intercalate between cancer cells, thereby promoting cancer dispersal from the tumor and migration toward the neuron. These steps ultimately lead to perineural invasion.

[Source 16 ]Perineural invasion treatment

Patients with extensive perineural invasion (PNI) should be offered adjuvant radiation therapy. Focal perineural invasion is a relative indication for adjuvant therapy.

Treatment of perineural spread (PNS) may be accomplished with surgery and/or radiotherapy; perineural spread involving proximal cranial nerves (base of skull) requires tertiary or quaternary multidisciplinary head and neck management.

Image-guided radiation therapy is used to verify accurate delivery of intensity-modulated radiation therapy, and may provide an additional advantage in radiotherapeutic management of complex targets close to critical structures, of relevance for head and neck tumors with perineural spread (PNS).

The role of systemic therapies in the management of perineural invasion and perineural spread remains unclear.

References- Liebig C, Ayala G, Wilks JA, Berger DH, Albo D. Perineural invasion in cancer: a review of the literature. Cancer 115(15), 3379–3391 (2009).

- Bapat AA, Hostetter G, Von Hoff DD, Han H. Perineural invasion and associated pain in pancreatic cancer. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11(10):695–707. doi: 10.1038/nrc3131

- Zhang Z, Liu R, Jin R, et al. Integrating Clinical and Genetic Analysis of Perineural Invasion in Head and Neck Squamous Cell Carcinoma. Front Oncol. 2019;9:434. Published 2019 May 31. doi:10.3389/fonc.2019.00434 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6555133

- Leslie SW, Soon-Sutton TL, Sajjad H, et al. Prostate Cancer. [Updated 2019 Oct 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2019 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470550

- Azam SH, Pecot CV. Cancer’s got nerve: Schwann cells drive perineural invasion. J. Clin. Invest. 2016 Apr 01;126(4):1242-4.

- Scheuermann DW, Krammer HJ, Timmermans JP, et al. Fine structure of morphologically well-defined type II neurons in the enteric nervous system of the porcine small intestine revealed by immunoreactivity for calcitonin gene-related peptide. Acta Anat (Basel) 1991;142:236-41. 10.1159/000147195

- Zhu Y, Zhang GN, Shi Y, Cui L, Leng XF, Huang JM. Perineural invasion in cervical cancer: pay attention to the indications of nerve-sparing radical hysterectomy. Ann Transl Med. 2019;7(9):203. doi:10.21037/atm.2019.04.35 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6545317

- Fagan JJ, Collins B, Barnes L, et al. Perineural invasion in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 1998;124:637-40. 10.1001/archotol.124.6.637

- Liebig C, Ayala G, Wilks JA, et al. Perineural invasion in cancer: a review of the literature. Cancer 2009;115:3379-91. 10.1002/cncr.24396

- Chi AC, Katabi N, Chen HS, et al. Interobserver variation among pathologists in evaluating perineural invasion for oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck Pathol 2016;10:451-64. 10.1007/s12105-016-0722-9

- Schmitd LB, Beesley LJ, Nickole R, et al. Redefining perineural invasion: integration of biology with clinical outcome. Neoplasia 2018;20:657-67. 10.1016/j.neo.2018.04.005

- Paes FM, Singer AD, Checkver AN et-al. Perineural spread in head and neck malignancies: clinical significance and evaluation with 18F-FDG PET/CT. Radiographics. 2013;33 (6): 1717-36. doi:10.1148/rg.336135501

- Gaddikeri S. Perineural Invasion of Skin Cancers in the Head and Neck: An Uncommon Phenomenon Revisited. Otolaryngology.2014 (03): . doi:10.4172/2161-119X.1000169

- Walton H, Morley S, Alegre-Abarrategui J. A rare case of atypical skull base meningioma with perineural spread. (2015) Journal of radiology case reports. 9 (12): 1-14. doi:10.3941/jrcr.v9i12.2648

- Kolokythas A, Cox DP, Dekker N, Schmidt BL. Nerve growth factor and tyrosine kinase A receptor in oral squamous cell carcinoma: is there an association with perineural invasion? J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 68(6), 1290–1295 (2010

- Azam SH, Pecot CV. Cancer’s got nerve: Schwann cells drive perineural invasion. J Clin Invest. 2016;126(4):1242–1244. doi:10.1172/JCI86801 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4811122