Meniscal cyst

The meniscus is a cartilage pad that serves as a shock absorber, provides stress transmission, enhances lubrication and facilitates nutrition to the knee. When the meniscus is torn, a small cyst can form adjacent to the tear. Meniscal cyst is thought to develop as part of the body’s healing response. Meniscal cysts occur when synovial fluid becomes encysted, often secondary to a meniscal tear. When they extend beyond the margins of the meniscus they are termed parameniscal cysts. Alone, a meniscal cyst is of little consequence and is present only secondary to the meniscus tear. However, the meniscal cyst itself can discomfort and may be noticeable over the joint line where the meniscus is torn.

Meniscal cysts were first reported in the literature in 1883 and the first detailed description was recorded in 1904 1. Meniscal cysts are relatively rare with reported incidence ranging from 1‐8% in both histologic and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies 2. Meniscal cysts have been reported most frequently in 20‐30 year old males 1. Meniscal cysts are commonly thought to result from a combination of trauma and meniscal degeneration,with subsequent introduction of synovial fluid due to motion forces 3. A tortuous cystic tract then develops at the periphery of the meniscus and acts as a one-way valve, preventing synovial fluid from re-entering the knee joint 4. The most common current theory of cyst development is they result from extrusion of synovial fluid through an adjacent meniscal tear 5.

Until recently, clinicians believed cysts of the lateral meniscus were more common than cysts of the medial meniscus. Authors of recent studies utilizing advanced imaging techniques and arthroscopic visualization estimate that 59‐66% of cysts occur medially, while 34‐41% occur laterally 6. Medial meniscal tears are reported more frequently than lateral meniscal tears 7, although isolated lateral meniscus tears in high‐level athletes may be more common 8.

The physical characteristics of meniscal cysts are varied. They may present as parameniscal cysts, which are typified on MRI by a loculated fluid‐intensity lesion with a clear connection to the adjacent meniscus 6. They may also appear as intrameniscal cysts, which are defined as abnormally increased signal within an enlarged meniscus 6. Reports of cysts associated with a palpable mass are also varied. Medial and lateral cysts were palpable on physical examination in 16% of a cohort including over 2,500 MRI reports 5. Parameniscal cysts of the lateral meniscus are more commonly palpable with 20‐60% of lateral cysts being detectable, while only 6% of medial cysts are palpable 2. Sizes may range from 0.1–8.0 cm, with an average size of 1–2 cm 6.

Anatomy of the knee

The anatomy and function of the knee are quite complex, and only the basics are described in this article. The knee is a hinge joint, situated between the thigh bone (femur) and shin bones (tibia and fibula) (Figure 1).

The knee is the largest joint in the body, and one of the most easily injured. It is made up of four main things: bones, cartilage, ligaments, and tendons.

- Bones. Three bones meet to form your knee joint: your thighbone (femur), shinbone (tibia), and kneecap (patella).

- Articular cartilage. The ends of the femur and tibia, and the back of the patella are covered with articular cartilage. This slippery substance helps your knee bones glide smoothly across each other as you bend or straighten your leg.

- Meniscus. Two wedge-shaped pieces of meniscal cartilage act as “shock absorbers” between your femur and tibia. Different from articular cartilage, the meniscus is tough and rubbery to help cushion and stabilize the joint. When people talk about torn cartilage in the knee, they are usually referring to torn meniscus.

- Ligaments. Bones are connected to other bones by ligaments. The four main ligaments in your knee act like strong ropes to hold the bones together and keep your knee stable.

- Collateral Ligaments. These are found on the sides of your knee. The medial collateral ligament is on the inside of your knee, and the lateral collateral ligament is on the outside. They control the sideways motion of your knee and brace it against unusual movement.

- Cruciate ligaments. These are found inside your knee joint. They cross each other to form an “X” with the anterior cruciate ligament in front and the posterior cruciate ligament in back. The cruciate ligaments control the back and forth motion of your knee.

- Tendons. Muscles are connected to bones by tendons. The quadriceps tendon connects the muscles in the front of your thigh to your patella. Stretching from your patella to your shinbone is the patellar tendon.

Contraction of the muscles on the front of the thigh (quadriceps) straightens the leg, while contraction of the muscles on the back of the thigh (the hamstrings) allows the leg to bend at the knee. The end of the femur rests in the shallow cup of the tibia (the tibial plateau), cushioned by a thick layer of cartilage (medial meniscus and lateral meniscus).

The bony structures of the knee include the distal femoral condyles, proximal tibial plateau and patella (Figure 1). The tibial plateau articulates with the femoral condyles, and the patellofemoral groove (located anteriorly between the femoral condyles) accepts the patella. At the front of the knee joint, the kneecap or patella sits in a groove at the lower end of the femur. The tibia and patella do not articulate. The gliding motion of the patella across the femur allows smooth extension at the knee and increases the mechanical advantage of the quadriceps. The bones are held in place by tough bands of connective tissue called ligaments. The entire joint is enclosed inside a tough capsule lined with a membrane and filled with lubricating synovial fluid. Extra capsules of fluid, known as bursae, offer extra cushioning.

The extra-articular muscle-tendon units include the quadriceps and patellar tendons (responsible for knee extension), medial and lateral hamstrings (chiefly responsible for knee flexion), gastrocnemius muscle, popliteal ligament and iliotibial band (Figure 3).

The extra-articular ligamentous structures include the tibial and fibular collateral ligaments (Figure 1). These ligaments act as the principal extra-articular static stabilizing structures (i.e., they provide stability for the medial and lateral aspects of the knee).

The intra-articular structures include the medial and lateral menisci and the anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments (Figure 1). The menisci are fibrocartilaginous wedges that rim and cushion each tibiofemoral articulation. The anterior and posterior cruciate ligaments provide stability for the knee joint.

Figure 1. Anatomy of the knee

Meniscal cyst causes

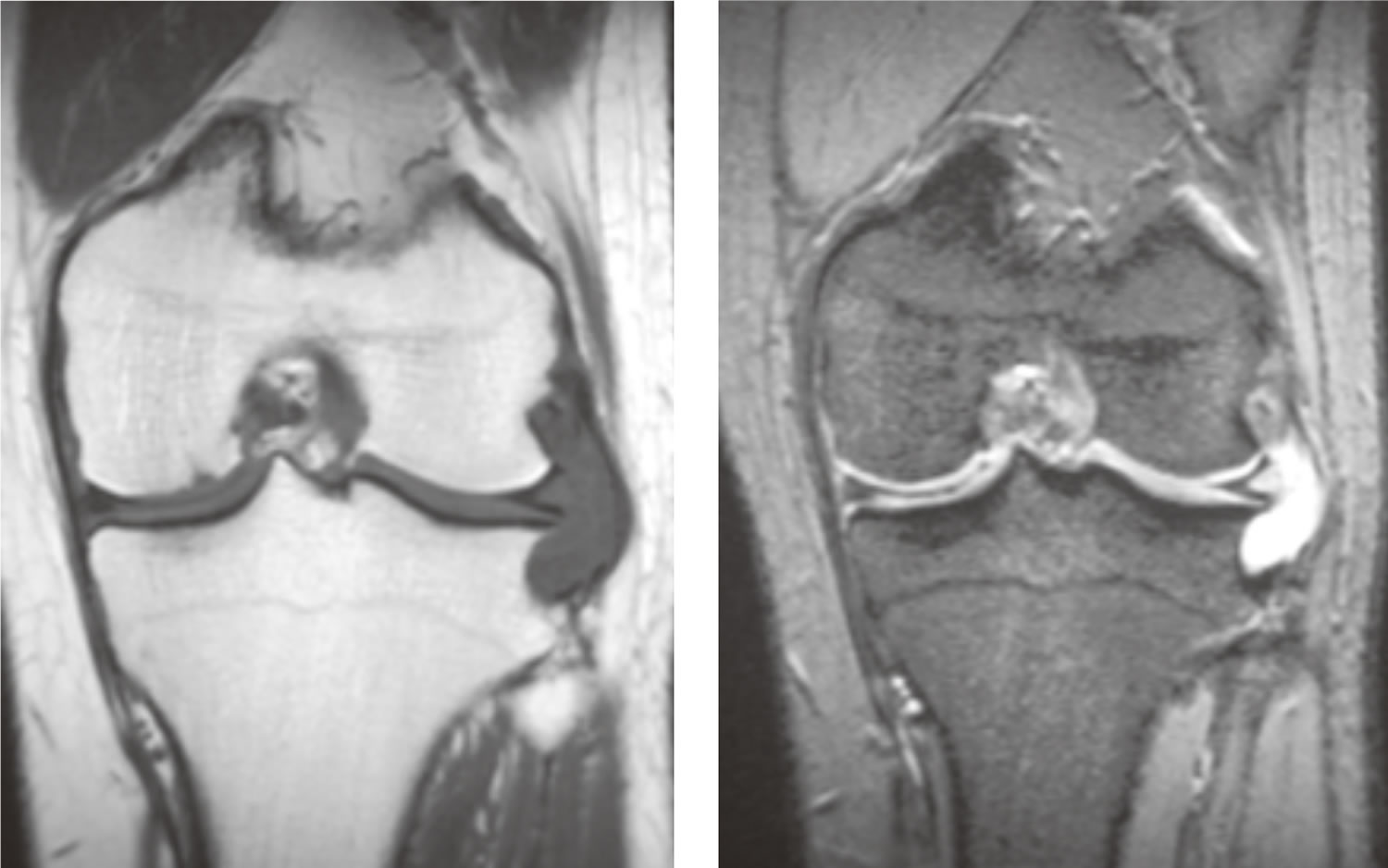

There are multiple theories regarding the cause of meniscal cysts. Meniscal cysts are often seen with meniscal tears that occur due to degenerative changes within the meniscus, although there may be an associated injury to the knee (pivoting or twisting injury). The majority of meniscal cysts are associated with underlying meniscal tears. Meniscal tears have been reported in association with meniscal cysts in 50‐100% of cases 2. The presence of a meniscal tear on MRI is defined as distinct high signal extending to an articular surface of the meniscus 5. MRI often shows a simple horizontal cleavage tear or a complex meniscal tear with a horizontal component that directly communicates with the adjacent cyst 5. Frequently, meniscal cysts are asymptomatic and are found incidentally on MRI performed to assess for other intra‐articular pathology such as internal derangement or chondral abnormality 6. Because 40‐50% of meniscal cysts are associated with an articular surface meniscal tear, the absence of this finding does not rule out the possibility of a cyst 6.

Surgical and arthroscopic series report lateral meniscal cysts as a more frequent occurrence as compared to their medial counterparts. A systematic review of MR literature says that the frequency of medial and lateral meniscal cysts is almost equal 9. In ~4% of cases, meniscal cysts may involve both menisci within the same knee 10.

Risk factor for meniscal cyst

- Twisting, turning sports, in which the menisci can be torn

- Previous knee injury

- Associated knee injury, particularly ligament injuries

- Age, in which degenerative meniscus tears increase in frequency

Meniscal cyst symptoms

Clinically the patient with meniscal cysts may present with a palpable soft tissue swelling, with or without knee pain.

Meniscal cyst symptoms may include:

- Pain, especially when standing on the affected leg, and tenderness along the joint of the knee

- Firm bump at the site of the cyst, more commonly over the lateral (outside) aspect of the knee

- Cyst may become more apparent as knee is extended

- Occasionally, a painless bump

- Associated non-specific findings may include knee swelling, joint line tenderness over the affected meniscus, “locking” of the joint or ligament injury.

Meniscal cyst diagnosis

Diagnosis is usually readily apparent by inspection and palpation of a discrete mass directly over a tender medial or lateral joint line. Diagnosis is confirmed by MRI, which shows both the cyst and the associated meniscus tear. Meniscal cyst should not be confused with a “Baker’s cyst”, which is a collection of fluid that most commonly accumulates on the medial (inside) back of the knee. When the knee becomes swollen for any reason, fluid can expand this space and form a cyst.

- MRI can confirm the diagnosis and establish the size and location of the cyst

- Ultrasound can also help to visualize the cyst, and guide aspiration, in which a needle is placed into the cyst to draw out its contents

Meniscal cyst treatment

If incidental or minimally symptomatic, treatment may require occasional icing and/or anti-inflammatory medicine. Meniscal cyst may be aspirated using local anesthetic and a small needle to remove the cysts’ contents. However, this is usually only temporarily effective, and the fluid returns. Some physicians may advocate instilling a small amount of cortisone into the cyst.

Surgery may be recommended as definitive treatment. Surgical excision of the cyst can be performed along with repair of the underlying meniscal tear.

Based on imaging findings treatment of a meniscal cyst differs:

- if a communicating meniscal tear present, it can be treated arthroscopically, in which a small camera is introduced into the knee joint, and another small portal (opening) is made to permit instruments to be brought into the joint. During arthroscopy, the torn meniscus is surgically debrided (removed). The associated meniscal cyst will then be decompressed.

- if a noncommunicating meniscal tear present, open surgery is required

When can you return to your sport or activity?

Although meniscus cysts do not “heal,” they may become asymptomatic over time, particularly with activity modification. If the cyst is not symptomatic, there is no reason one cannot participate in activities. If surgery is performed to address the meniscus and decompress the cyst, the patient may be able to return to activity as early at 3 weeks post-operatively.

References- Lantz B, Singer KM. Meniscal cysts. Clin Sports Med. 1990;9(3):707–725

- De Smet AA, Graf BK, del Rio AM. Association of parameniscal cysts with underlying meniscal tears as identified on MRI and arthroscopy. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196(2):W180–186

- Sarimo J, Rainio P, Rantanen J, Orava S. Comparison of twoprocedures for meniscal cysts: a report of 35 patients with a meanfollow-up of 33 months. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:704-7.

- Sarimo J, Rainio P, Rantanen J, Orava S. Comparison of two procedures for meniscal cysts: a report of 35 patients with a meanfollow-up of 33 months. Am J Sports Med 2002;30:704-7.

- Campbell SE, Sanders TG, Morrison WB. MR imaging of meniscal cysts: incidence, location, and clinical significance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177(2):409–413

- Anderson JJ, Connor GF, Helms CA. New observations on meniscal cysts. Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39(12):1187–1191

- Poulsen MR, Johnson DL. Meniscal injuries in the young, athletically active patient. Phys Sportsmed. 2011;39(1):123–130

- Yeh PC, Starkey C, Lombardo S, Vitti G, Kharrazi FD. Epidemiology of isolated meniscal injury and its effect on performance in athletes from the National Basketball Association. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40(3):589–594

- Campbell SE, Sanders TG, Morrison WB. MR imaging of meniscal cysts: incidence, location, and clinical significance. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2001;177 (2): 409-13. https://www.ajronline.org/doi/full/10.2214/ajr.177.2.1770409

- Anderson JJ, Connor GF, Helms CA. New observations on meniscal cysts. Skeletal Radiol. 2010 Dec;39(12):1187-91. doi: 10.1007/s00256-010-0993-2. Epub 2010 Jul 31. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007%2Fs00256-010-0993-2