Primary ovarian insufficiency

Primary ovarian insufficiency also called premature ovarian failure or premature menopause, is the permanent end of menstrual periods before age 40. “Primary ovarian insufficiency” is the preferred term advocated by the National Institutes of Health because ovarian function is intermittent or unpredictable in many cases. Primary ovarian insufficiency occurs because the ovaries no longer release eggs (ovulation) regularly and become less able to produce hormones. Primary ovarian insufficiency is not the same as early menopause. Some women with primary ovarian insufficiency still get a period now and then. But ovulation problems can make getting pregnant hard for women with primary ovarian insufficiency. There is no consensus on criteria to identify primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents, and delay in diagnosis is common 1.

Some women have no symptoms except being unable to become pregnant, and others have the same symptoms as those of natural menopause (such as hot flashes or night sweats).

Blood tests can confirm the diagnosis, and other tests are done to identify the cause.

Various measures, including estrogen (typically taken until about age 51, when menopause occurs on average), can relieve or reduce symptoms.

To become pregnant, women with premature menopause can have eggs from another woman implanted in their uterus.

Hormonally, primary ovarian failure resembles natural menopause. The ovaries produce very little estrogen. Ovulation stops. However, sometimes the ovaries start functioning for a short time and can release an egg, making pregnancy possible. The ovaries still contain thousands of eggs. Because 5–10% of women with primary ovarian insufficiency experience spontaneous conception and birth, primary ovarian insufficiency can be distinguished from natural menopause and also may be described as decreased ovarian reserve 2.

What causes primary ovarian insufficiency?

Follicle depletion or dysfunction in adolescents may be caused by many different factors. It is often caused by chromosomal abnormalities or damage from chemotherapy or radiation therapy. It is also associated with a premutation in the FMR1 gene for fragile X. Primary ovarian insufficiency may be associated with multiple endocrinopathies, including hypoparathyroidism and hypoadrenalism. Less frequently, it can result from infiltrative or infectious processes 3. Pelvic surgery also may lead to impairment of ovarian function. Approximately 4% of women who have primary ovarian insufficiency will have adrenal or ovarian antibodies, which suggests an autoimmune mechanism for disease 4. In many cases, the cause remains unknown 5.

Causes of spontaneous primary ovarian insufficiency 5:

- Ovarian follicle dysfunction

- Signal defect

- FSH-receptor mutation: Presence of ovarian follicles confirmed by biopsy; founder effect; rare disorder outside of Finland

- Luteinizing hormone-receptor mutation: Ovarian follicles present on ultrasound examination; rare disorder

- G-protein mutation: Secondary amenorrhea, elevated gonadotropin levels, and hypoestrogenemia that responded to gonadotropin therapy developed in patient with pseudohypoparathyroidism 6; rare disorder

- Enzyme deficiency

- Isolated 17,20-lyase deficiency: Ovarian follicles present on biopsy, “moderate ovarian enlargement” due to block in estradiol synthesis; rare disorder

- Aromatase deficiency: Ovarian enlargement or hyperstimulation due to inability of the ovary to aromatize and rostenedione to estradiol; rare disorder

- Autoimmunity

- Autoimmune lymphocytic oophoritis: Antral follicles with lymphocytic infiltration into theca, primordial follicles spared, multifollicular ovaries; accounts for 4% of cases of 46,XX primary ovarian insufficiency; associated with evidence of adrenal autoimmunity

- Insufficient follicle number

- Luteinized Graafian follicles: Antral follicles imaged by ultrasonography in 40% of patients with idiopathic spontaneous 46,XX primary ovarian insufficiency; on the basis of histologic findings, at least 60% of antral follicles imaged in these patients are luteinized, a major mechanism of follicle dysfunction in these women7

- Signal defect

- Ovarian follicle depletion

- Insufficient initial follicle number

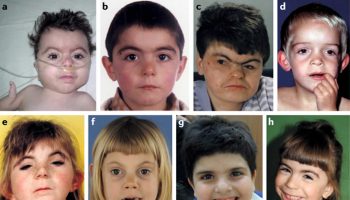

- Blepharophimosis, ptosis, epicanthus inversus syndrome Mutation in FOXL2 is a mechanism of familial primary ovarian insufficiency, and disruption of the mouse gene causes a pervasive block in primordial follicle development; rare disorder

- Spontaneous accelerated follicle loss

- Turner’s syndrome: Although a normal complement of primordial follicles is established in the ovary during fetal development, follicle loss through apoptosis is accelerated so that the store of primordial follicles is typically depleted before puberty; in oocytes, both X chromosomes must be present and remain active to prevent accelerated follicular atresia; the individual genes responsible for this ovarian syndrome have not been identified

- Insufficient initial follicle number

- Environmental-toxin–induced follicle loss

- Industrial exposure to 2-bromopropane: Exposure to cleaning solvent associated with primary ovarian insufficiency in 16 Korean women 7

Chromosomal abnormalities

A common cause of primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents is gonadal dysgenesis, with or without Turner syndrome 3. When adolescents present with primary amenorrhea and no associated comorbidities, 50% are found to have abnormal karyotypes. Among younger women (aged 30 years or younger) with secondary amenorrhea, 13% also have been noted to have an abnormal karyotype 8. Although pubertal and growth delays are common in this group, many affected females may first be recognized at the time of evaluation for menstrual abnormalities.

Chemotherapy and radiation therapy

The immediate loss of ovarian function after chemotherapy or radiation therapy is termed “acute ovarian failure,” which may be transient. With chemotherapy, the age of the patient when she received chemotherapy, types of medication, and number of doses all have an effect on the possibility of gonadotoxicity. Although the highest incidence of acute ovarian failure occurs after the use of alkylating agents or procarbazine, the younger the patient at the time of receiving the chemotherapy, the more likely it is that some follicles will survive 9. Whole-body, whole-brain, pelvic, and spinal irradiation also increase the risk of acute ovarian failure (9). Pelvic irradiation (especially doses more than 10 Gy) is a significant risk factor for acute ovarian failure 9. Chemotherapy combined with radiation therapy increases the chance of acute ovarian failure. It should be noted that even females who menstruate after chemotherapy have an increased lifetime risk of primary ovarian insufficiency 10.

Fragile X syndrome

Fragile X syndrome is the most common form of hereditable mental retardation. Among females with primary ovarian insufficiency and a normal karyotype, 6% have a premutation in the FMR1 gene 8. Although the onset of menstruation appears to be normal among premutation carriers in adolescence, approximately 1% of premutation carriers will experience their final menses before age 18 years 11. If a woman has a personal or family history of ovarian failure or an elevated follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) level before age 40 years without a known cause, fragile X premutation carrier testing should be offered 12.

Primary ovarian insufficiency signs and symptoms

Some women may have no symptoms, except that they cannot become pregnant. Other women develop the same symptoms that are associated with normal menopause (which occurs at about age 51), such as hot flashes, night sweats, or mood swings. Menstrual periods may become lighter or irregular, or they may stop.

The lack of estrogen may lead to decreased bone density (osteoporosis) and thinning and drying of the lining of the vagina (vaginal atrophy). If women with premature menopause do not take estrogen therapy until they reach the average age for menopause (about age 51), the risk of mood disorders, Parkinson disease, dementia, and coronary artery disease is increased.

If the cause is a disorder that confers a Y chromosome, the risk of cancer of the ovaries is increased.

Women may have symptoms of the disorder causing premature menopause. For example, if Turner syndrome is the cause, they may be short and have a webbed neck and learning disabilities.

Primary ovarian insufficiency possible complications

Primary ovarian insufficiency increases the risk of bone loss, cardiovascular disease, and endocrine disorders.

Bone loss

Loss of ovarian function at an early age affects bone architecture at the very time when bone accrual is at its maximum. There are no published data to support specific recommendations for dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry scanning in adolescents with estrogen deficiency. Although some experts suggest monitoring bone density annually in adolescents with estrogen deficiency during early to mid puberty to document peak bone accrual and then every 2 years in late adolescence, others do not because the implications of a low bone mineral density result in this population are unclear given the low risk of fracture and the potential for long-term treatment of low bone mass. To date, long-term use of bisphosphonates is not recommended in the adolescent population because of uncertain adverse effects and safety profiles. Further research in this area is needed.

Cardiovascular disease

Individuals with early loss of endogenous estrogen have been shown to have an increased risk of cardiovascular mortality 13. Although data in the adolescent population are lacking and there are no standard screening regimens for cardiovascular disease in this population, vigilant monitoring is warranted, and practitioners should help patients optimize cardiovascular health. Routine visits should include counseling on tobacco avoidance and appropriate diet and exercise to optimize cardiovascular health. Measuring blood pressure at least annually and lipid levels every 5 years is recommended. Patients with Turner syndrome have additional cardiovascular risks, including aortic aneurysm. Additional guidelines for patients with Turner syndrome and no obvious cardiovascular pathology include either routine cardiac imaging every 5–10 years or focused imaging when transitioning from a pediatric to adult health care provider, before attempting pregnancy, or with the appearance of hypertension to assess for coarctation or aortic stenosis 14. Although early loss of ovarian function has been associated as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality, there are no data indicating that these patients are at an increased risk of cardiovascular adverse effects from hormonal therapy 15.

Endocrine disorders

Approximately 20% of adults with idiopathic primary ovarian insufficiency will experience hypothyroidism, most commonly Hashimoto thyroiditis 8. Following initial diagnosis of primary ovarian insufficiency, it is appropriate to test thyrotropin levels for the presence of thyroid peroxidase antibodies. Although no recommendations for routine thyroid screening exist in this population, given the high prevalence of this disorder in patients with primary ovarian insufficiency, it is acceptable to test for thyroid disease every 1–2 years. Patients with primary ovarian insufficiency also have a 50% chance of developing adrenal insufficiency if they have adrenal autoimmunity. Patients should be tested for adrenal anti-bodies and if results are positive, should undergo yearly corticotropin stimulation testing. Data are lacking on the follow-up of patients with negative test results 16. Diabetes mellitus, pernicious anemia, myasthenia gravis, rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus, and dry eye syndrome also have been associated with primary ovarian insufficiency, and testing should be based on symptomatology. Antiovarian antibodies may be present in these patients, but their specificity and pathogenic usefulness has not been validated 15.

Primary ovarian insufficiency diagnosis

There is no consensus on criteria to identify primary ovarian insufficiency in adolescents, and delay in diagnosis is common. Doctors suspect primary ovarian insufficiency when women younger than 40 have menopausal symptoms or cannot become pregnant. Some adolescent females will report hot flushes or vaginal symptoms like dryness or dyspareunia, the most common presenting symptom of primary ovarian insufficiency is primary or secondary amenorrhea. Among patients with amenorrhea, the incidence of primary ovarian insufficiency ranges from 2% to 10% 3. Abnormal bleeding patterns also may include oligomenorrhea (bleeding that occurs less frequently than every 35 days), nonstructural causes of abnormal uterine bleeding (eg, ovulatory dysfunction, iatrogenic, or not yet classified), or polymenorrhea (bleeding that occurs more often than every 21 days) 17. Because irregular menstrual cycles are both common during early adolescence and an initial symptom of early primary ovarian insufficiency, diagnosis can be difficult in this population. Although less than 10% of women who present with abnormal menses will ultimately be found to have primary ovarian insufficiency, the condition has such detrimental consequences on bone health that early diagnosis of this condition is important 18. Therefore, in young females it is important to evaluate amenorrhea or a change from regular to irregular menses for 3 or more consecutive months in the absence of hormonal preparations such as oral contraceptives (OCs) for all potential causes, including pregnancy, polycystic ovary syndrome, hypothalamic amenorrhea, thyroid abnormalities, hyperprolactinemia, and primary ovarian insufficiency 18. Inquiries should be made about family medical history because females with a family history of early menopause are at risk of primary ovarian insufficiency 19.

Initial laboratory evaluation for suspected primary ovarian insufficiency includes measurements of basal FSH (follicle-stimulating hormone) and basal estradiol levels and tests to rule out causes such as pregnancy, thyroid disease, and hyperprolactinemia. Gonadotropin and estradiol values may be altered by concomitant use of hormonal preparations and thus should only be obtained in patients who are not taking hormonal medications, including oral contraceptives. If gonadotropins are elevated into the menopausal range (typically, basal FSH levels will be greater than 30–40 mIU/mL, depending on the laboratory used), a repeat FSH measurement is indicated in 1 month. If the result indicates that FSH is elevated, a diagnosis of primary ovarian insufficiency can be established. Estradiol levels of less than 50 pg/mL indicate hypoestrogenism.

Antimüllerian hormone and inhibin B are being evaluated to determine their value in the diagnosis of primary ovarian insufficiency. With further research, antimüllerian hormone testing may become increasingly valuable in assessing ovarian reserve before and after chemotherapy for young women with cancer, before and after ovarian surgery, and for females at high risk of primary ovarian insufficiency 20. However, there is significant variability in inhibin B levels between menstrual cycles. This marker does not reliably predict a poor response to ovarian stimulation, and thus, inhibin B is not a recommended test.

Surrogate markers of ovarian reserve (presence of regular menses, serial serum estradiol levels, and antral follicle count by transvaginal ultrasonography) are highly variable and are not predictive of future fertility or hormonal production in young women who have undergone treatment for cancer 21, but are currently undergoing investigation. Once a diagnosis of primary ovarian insufficiency is established, further testing, including karyotype, adrenal antibodies, FMR1 premutation, and pelvic ultrasonography, may be indicated to investigate possible etiologies of primary ovarian insufficiency.

Initial evaluation of primary ovarian insufficiency 5:

Diagnosis of primary ovarian insufficiency:

- Menstrual irregularity for at least 3 consecutive months

- Follicle-stimulating hormone and estradiol levels (two random tests at least 1 month apart)

- Prolactin and thyroid function test

If diagnosis is confirmed:

- Karyotype

- FMR1 permutation

- Adrenal antibodies

- 21-hydroxylase (CYP21) by immunoprecipitation or by indirect immunofluorescence

- Pelvic ultrasonography

Primary ovarian insufficiency treatment

Hormonal Therapy

For adolescents with primary ovarian insufficiency, the objective of treatment is to replace the hormones that the ovary would be producing before the age of menopause, making the treatment distinctly different from hormonal therapy for menopause that focuses on the treatment of menopausal symptoms. The goals of hormonal therapy extend beyond simply symptom relief to levels that support bone, cardiovascular and sexual health. Regardless of the cause, patients with primary ovarian insufficiency are estrogen deficient. Thus, young women with primary ovarian insufficiency may need higher doses of estrogen than menopausal women to ensure adequate replacement and optimal bone health 18. In girls with absent or incomplete breast development, estrogen therapy should be initiated and increased slowly before administration of graduated progesterone dosages until breast development is complete to prevent tubular breast formation. For those patients who have not initiated or completed pubertal growth and sexual maturity, consultation with a specialist in growth and development and hormonal therapy in children is recommended.

If women with primary ovarian failure do not wish to become pregnant, they are given one of the following:

- Birth control pills that contains estrogen and a progestin (combination oral contraceptives)

- Hormone therapy that contains a higher dose of estrogen, taken every day, and a progestin or progesterone, taken for 12 to 14 days each month (cyclical hormone therapy). Estrogen helps relieve symptoms and helps prevent other effects of menopause (such as vaginal dryness, and mood swings). The higher dose of estrogen in hormone therapy helps maintain bone density. Because taking estrogen alone increases the risk of cancer of the uterine lining (endometrial cancer), most women also take a progestin or progesterone with the estrogen to help protect against this cancer. Women who no longer have a uterus may take estrogen alone.

- If pregnancy is desired, in vitro fertilization (IVF). Another woman’s eggs (donor eggs) are implanted in the uterus after they have been fertilized in the laboratory. Estrogen and a progestin or progesterone are also given to enable the uterus to support the pregnancy. This technique gives women up to a 50% chance of becoming pregnant. Otherwise the chance of becoming pregnant is less than 10%. The age of the woman donating the eggs is more important than the age of the woman receiving them. Even without in vitro fertilization, some women with primary ovarian insufficiency become pregnant.

Once pubertal development is complete, ongoing hormonal therapy will be necessary for long-term health. Hormonal support involves daily therapy with the goal of maintenance of normal ovarian functioning levels of estradiol. Transdermal, oral, or occasionally transvaginal estradiol in doses of 100 micrograms daily is the therapy of choice to mimic a physiologic dose range and to achieve symptomatic relief. The addition of cyclic progesterone for 10–12 days each month is protective against endometrial hyperplasia and endometrial cancer, risks of unopposed estrogen. Oral estradiol may be used, but it increases the potential for thromboembolism relative to transdermal estradiol due to the first-pass effect on the liver. Oral contraceptives contain higher doses of estrogen than are necessary for hormonal therapy; therefore, they are not recommended as first-line hormonal therapy.

Women who have a Y chromosome need to have their ovaries removed to decrease the risk of developing ovarian cancer. Hormone therapy is usually also recommended for these women until they reach the average age of menopause or longer to prevent the effects of the lack of estrogen.

Fertility and Contraception

Fertility may persist even when few functional follicles are present. Because of occasional spontaneous resumption of ovarian function, there is a 5–10% chance of spontaneous pregnancy despite a diagnosis of primary ovarian insufficiency 11. Unless pregnancy is desired, a discussion of effective contraception should take place. Although birth control pills (oral contraceptives) are commonly prescribed in this situation, the use of barrier methods or an intrauterine device is encouraged 16. If a patient chooses a nonestrogen method of contraception, estrogen also should be administered to preserve bone mineral density and prevent other adverse effects of hypoestrogenemia. A missed menstrual cycle should warrant a pregnancy test.

Patient Counseling

When primary ovarian insufficiency is diagnosed in the adolescent female, the patient and her family are often unprepared for such news with its implications for compromised fertility and impaired self-image and the need for long-term hormonal therapy. It is best to inform the patient and family by having a direct conversation in the office. Adolescents may demonstrate myriad emotions ranging from apathy or denial to remorse or sadness, and these emotions may be different from those of their parents or guardians. Practitioners can consider telling the parents separately from their children so that the parents will have an opportunity to understand the diagnosis and adjust their demeanor to be most supportive of their daughters. Parents also can provide valuable insights about their daughters’ ability to appreciate the significance of the diagnosis of primary ovarian insufficiency and guide the clinician or team. Health care providers who make this clinical diagnosis should be mindful of the sensitive nature of this medical condition as well as the cultural significance of the diagnosis within the family unit. Use of the term “premature ovarian failure” can be particularly troubling to a young woman and her family 3. “Insufficiency” is the more accepted term in this population and more truly reflects the possibility of intermittent resumption of function. Patients and their families should be counseled on the effect of the patient’s condition on future fertility. Referrals to a reproductive endocrinology and infertility specialist should be made when desired by the patient and family to further discuss available reproductive treatments. In vitro fertilization with donor oocytes is often the most appropriate treatment; there are otherwise limited therapeutic options. Although the procedure may not be ideal, it may provide some hope for the patient who is told that her fertility is severely compromised. However, this is not a recommended option for patients with Turner syndrome because of the risk of aortic rupture during pregnancy. Psychologic counseling also should be offered because impaired self-esteem and emotional distress have been reported after diagnosis of primary ovarian insufficiency 22.

- Primary Ovarian Insufficiency in Adolescents and Young Women. https://www.acog.org/Clinical-Guidance-and-Publications/Committee-Opinions/Committee-on-Adolescent-Health-Care/Primary-Ovarian-Insufficiency-in-Adolescents-and-Young-Women[↩]

- Testing and interpreting measures of ovarian reserve: a committee opinion. Practice Committee of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine. Fertil Steril 2012;98:1407–15.[↩]

- Rebar RW. Premature ovarian “failure” in the adolescent. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1135:138–45.[↩][↩][↩][↩]

- Rafique S, Sterling EW, Nelson LM. A new approach to primary ovarian insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am 2012;39:567–86.[↩]

- Nelson LM. Clinical practice. Primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(6):606–614. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp0808697 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2762081[↩][↩][↩]

- Wolfsdorf JI, Rosenfield RL, Fang VS, Kobayashi R, Razdan AK, Kim MH. Partial gonadotrophin-resistance in pseudo-hypoparathyroidism. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh) 1978;88:321–8.[↩]

- Koh JM, Kim CH, Hong SK, et al. Primary ovarian failure caused by a solvent containing 2-bromopropane. Eur J Endocrinol. 1998;138:554–6.[↩]

- Nelson LM, Covington SN, Rebar RW. An update: spontaneous premature ovarian failure is not an early menopause. Fertil Steril 2005;83:1327–32.[↩][↩][↩]

- Green DM, Sklar CA, Boice JD Jr, Mulvihill JJ, Whitton JA, Stovall M, et al. Ovarian failure and reproductive outcomes after childhood cancer treatment: results from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study. J Clin Oncol 2009; 27:2374–81.[↩][↩]

- Duffy C, Allen S. Medical and psychosocial aspects of fertility after cancer. Cancer J 2009;15:27–33.[↩]

- De Caro JJ, Dominguez C, Sherman SL. Reproductive health of adolescent girls who carry the FMR1 premutation: expected phenotype based on current knowledge of fragile x-associated primary ovarian insufficiency. Ann N Y Acad Sci 2008;1135: 99–111.[↩][↩]

- Carrier screening for fragile X syndrome. Committee Opinion No. 469. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol 2010;116:1008–10.[↩]

- van der Schouw YT, van der Graaf Y, Steyerberg EW, Eijkemans JC, Banga JD. Age at menopause as a risk factor for cardiovascular mortality. Lancet 1996;347:714–8[↩]

- Pinsker JE. Clinical review: Turner syndrome: updating the paradigm of clinical care. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2012; 97:E994–1003.[↩]

- Rebar RW. Premature ovarian failure. Obstet Gynecol 2009;113:1355–63.[↩][↩]

- Nelson LM. Clinical practice. Primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med 2009;360:606–14.[↩][↩]

- Nelson LM. Clinical practice. Primary ovarian insufficiency. N Engl J Med 2009;360:606–14[↩]

- Nelson LM. Spontaneous premature ovarian failure: young women, special needs. Menopause Manag 2001;10(4):1–6.[↩][↩][↩]

- Menstruation in girls and adolescents: using the menstrual cycle as a vital sign. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 349. Obstet Gynecol 2006;108:1323–8[↩]

- Nelson SM. Biomarkers of ovarian response: current and future applications. Fertil Steril 2013;99:963–9.[↩]

- Johnston RJ, Wallace WH. Normal ovarian function and assessment of ovarian reserve in the survivor of childhood cancer. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2009;53:296–302.[↩]

- Schmidt PJ, Cardoso GM, Ross JL, Haq N, Rubinow DR, Bondy CA. Shyness, social anxiety, and impaired self-esteem in Turner syndrome and premature ovarian failure. JAMA 2006;295:1374–6.[↩]