Pseudodementia

Pseudodementia is understood as a specific clinical entity, characterized by cognitive deficits, mimicking dementia, occurring in the background of functional psychiatric disorders, especially depression 1. One of the earliest reports of pseudodementia was published by Kiloh in 1961 2. Kiloh 2 described 10 cases of functional psychiatric disorders and considered pseudodementia as a purely descriptive term, which does not carry any diagnostic weight, commonly associated with depressive disorders. According to him, these patients had varying degrees of disturbances in memory, judgment, and intellectual functions such as comprehension, calculation, and knowledge 2.

Since then, pseudodementia has been used, rather loosely, to describe cognitive deficits occurring in depression, especially in the elderly, and no meaningful attempt has been made to set its characteristics within a nosographic framework 3. Over time, pseudodementia has continued to be poorly characterized neuropsychologically, and it has never been properly integrated into the currently used dementia classification systems 4. In the 1980s, it was included among the reversible or treatable “subcortical” forms of dementia, together with, for example, normotensive hydrocephalus and metabolic dementia 5. Subsequently, various attempts were made to redefine pseudodementia; according to one of these, pseudodementia is cognitive impairment of the dementia type that correlates positively with unipolar affective (mood) disorders, previous mood disorders and favorable outcomes, and negatively with non-depressive conditions and confusion disorders 6.

In the 1990s, however, it became more apparent that a depressive state associated with cognitive impairment can be the prodromal stage of dementia that is actually irreversible 7. In this regard, a more recent meta-analysis study found depression to be associated with a twofold increased risk of developing dementia 8. Along the same lines, an observational study found that over a period of at least five years, more than 70% of elderly patients initially presenting with pseudodementia converted to overt dementia, as opposed to 18% of subjects initially defined cognitively intact. These findings indicate that cognitive impairment in elderly individuals with moderate-to-severe depression is a strong predictor of dementia 9. Over the years, there has been increasing criticism of the term pseudodementia from authors who, on the basis of their clinical experience, consider it to be redundant and misleading, given that a complete history and thorough clinical examination of the patient are usually sufficient to establish a diagnosis 10. More recently, some authors have even stated that, among the “very old”, the presence of cognitive disorders in patients with depression, including those with a lifetime history of mood disorders, almost always indicates an incipient dementia process and should prompt the specialist to start an appropriate diagnostic and therapeutic workup for dementia 11. Furthermore, the DSM-5 12 identifies cognitive disorders as core symptoms of depression and includes several (difficulty thinking and concentrating and/or making decisions) among the diagnostic criteria for major depressive disorder. Although the DSM-5 acknowledges, in its commentary, that disorders of the cognitive sphere—particularly those involving memory—can persist following improvement or remission of depressive symptoms, and therefore be interpreted as the initial presentation of dementia, a definition of “reversible dementia caused by psychiatric illness” is not yet contemplated as a formal diagnostic category, contrary to what some authors recommend 13. On the other hand, it should always be remembered that, in depressed patients, reversible cognitive deficits can sometimes coexist with irreversible ones, and thus with true dementia 14.

After the term came into the academic use, there have been several arguments against its usage 15 as well as in favor of it 16. Inspite of these arguments, pseudodementia remains an important descriptive denotation for describing cognitive deficits in psychiatric disorders, especially depression.

It is now recognized, on the basis of observations and scientific evidence, that cognitive disorders are a core feature of the clinical picture of depression and should not be considered merely secondary to it; moreover, they are among the main causes of functional impairment in depressed patients. Cognitive symptoms should therefore be regarded as a partially independent dimension of major depressive disorder, and an important target of any treatment that is initiated 17.

Clinically, pseudodementia has become synonymous with the cognitive deficits seen in patients with major depressive disorder. As the term signifies, it is the clinical condition, which presents with the picture of a full-blown dementia but actually is a different entity. This means that actually this condition has two components, which is also reflected in its name:

- “The dementia component” which is the combination of various cognitive deficits found in these psychiatric disorders and

- “The pseudo component” which denotes the actual lack of the neurodegenerative dementia.

Both these components are important and the relationship between depression and dementia is complex and has been the topic of many debates recently. This complexity arises from the two facts that cognitive impairments can be found in depression 18 and that dementia can manifest with depressive symptoms as well.

Attention deficit and memory impairment are common in patients with pseudodementia, but cognitive deficit is more prominent in Alzheimer disease than pseudodementia. In some cases, it is difficult to differentiate pseudodementia from other types of dementia until full recovery from depression is achieved 19.

Till recent times, none of the studies systematically evaluated the differences in the cognitive profile and neuroimaging findings of patients with true dementia and pseudodementia. A recent study showed that there are significant differences between patients with Alzheimer’s dementia and depressive pseudodementia in terms of Wechsler Memory Scale, Clock-drawing test, Stroop test, Boston Naming Test, and Mini-Mental State Examination scores and left hippocampal volume 20.

Some authors use the term pseudo-pseudodementia when the patient presents with features of pseudodementia in the background of organic brain disease 21.

There are multiple reasons why there has to be a clearer understanding of pseudodementia. Most importantly, it needs to be properly understood because of the role it plays in the functional impairment of depressive disorders. In the recent review by McIntyre et al. 22, it was found that cognitive deficits accounted for the largest percentage of variance with respect to the link between psychosocial dysfunction and major depressive disorder. Thus, cognitive deficits are clearly important functional predictors of major depressive disorder.

Pseudodementia versus Dementia

The importance of distinguishing primary dementing processes from functional disorders has been highlighted time and again since Kiloh coined the term pseudodementia in 1961 2. In his own words, such patients “may be in danger of therapeutic neglect and perhaps of unnecessary neurosurgical investigations”. However, the author also mentioned that pseudodementia does not have any nosological significance and only describes a condition. Now, scientists know that pseudodementia is far more important to understand for establishing a diagnosis of either dementia or depression. The timely recognition and treatment of depression in the elderly is thus important not only to prevent the patient from the consequences of progressing depression but also to prevent them from unnecessary investigative evaluations for dementia. The difficulty in diagnostic assessments of pseudodementia and pervasive developmental disorder is particularly evident in elderly patients as compared to young adults because of the additional confusion created by age-related cognitive deficits. No wonder that there have been reports of high rates of both false-positive and false-negative errors in the diagnosis of dementia 23. This points the necessity of improved clinical diagnostic techniques. Along with this normal age-related cognitive decline, multiple health problems, and the common use of several different medications are often the additional factors obscuring appropriate diagnosis of depression in the aged people.

Saez-fonseca 24 found in their 5-7 year follow up study that 71.4% of those suffering from pseudodementia had converted into dementia at follow-up compared to only 18.2% of the conversion in the cognitively intact group. Kral & Emery 25 conducted a similar study of progression of pseudo-dementia. Forty-four elderly patients of both sexes (mean age 76.5 years) suffering from depressive pseudodementia were intensively treated for the depression. When the depression subsided, cognitive function also reverted to premorbid level. Patients were regularly interviewed and retested at six months intervals for four to 18 years (average 8). Some patients experienced, during the follow-up period, a recurrence of the depression for which they were again successfully treated. For testing the progression of these cognitive deficits with time, several different study designs have been used. Some studies have used the more direct method of comparing cross-sectionally the performance of subjects who have recovered from depression with that of matched controls. Paradiso et al. 26 found significant cognitive impairments on the set-shifting tasks in subjects who had recovered from unipolar depression as compared to normal controls. Additionally, these cognitive deficits were not related to medication status which suggested the independence of these deficits from treatment related variables. In the same line, Marcos et al. 27 found persistent deficits in both immediate memory and delayed recall of visual and verbal material, and block design in patients of melancholia after 3 months of their recovery.

Although these studies provide a cross-sectional perspective regarding poor neuropsychological performance of depressed patients in comparison to normal controls, definitive findings can only be provided by testing the cognitive status before and after recovery so that any baseline cognitive deficits are eliminated. Abas et al. 28 tested elderly patients with endogenous depression on several memory measures and reported that nearly half of those performing poorly at baseline were poor performers inspite of absence of clinically evident dementia or minimal cognitive deficits. In a similar sample of elderly patients, Beats et al.29 also found that many, but not all deficits had remitted upon recovery. Specifically, measures of simple and choice reaction times, perseveration on the set shifting task and verbal fluency did not fully recover.

One of the earliest and still most cited descriptions of cognitive deficits of pseudodementia was provided by Small et al 30. In their classical descriptions, depressive pseudodementia patients had equal loss for recent and remote events, were especially characterized by patchy or specific memory loss, their attention and concentration were intact and gave frequent “Don’t know” answers. More specifically, their performance on similarly difficult neuro-psychological tasks were much variable.

A clearer picture of this diagnostic dilemma was provided by Kaszniak 31 who delineated four clinically important reasons that make the differentiation between these two clinical states difficult:

- Cognitive changes in the elderly blur the distinction between normal aging and early signs of pervasive developmental disorder

- Cognitive impairment frequently accompanies depression and can be severe enough to cause confusion between dementia and depression

- Signs of some neurologic diseases associated with progressive decline (e.g., Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s disease) have symptoms that overlap with depression

- Dementia and depression can co-exist.

Pseudodementia causes

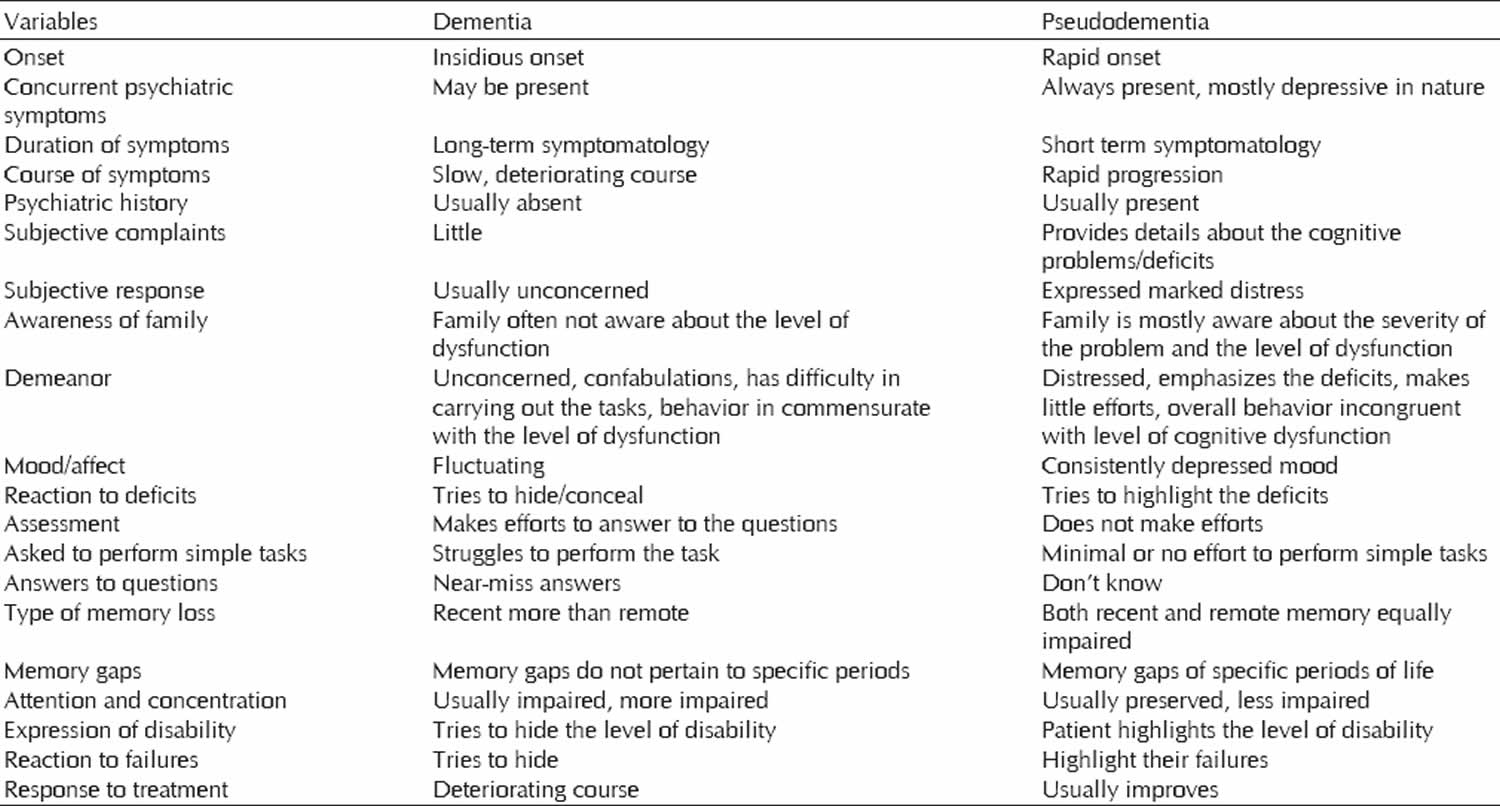

The term pseudodementia denotes occurrence of cognitive deficits in patients with psychiatric disorders, in the absence of actual neurodegenerative process 32. In clinical practice, it is extremely difficult to distinguish, early on, between cognitive impairment (degenerative or vascular) that is destined to advance and pseudodementia (depression-related cognitive impairment) that can be reversed. Although various features have been identified to help support this differential diagnostic process (see Table 1 below), on their own they are insufficient. Nevertheless, in recent years, there have been several interesting developments in this field. For example, it has been observed that on certain neuropsychological tests (the clock-drawing test, Stroop test, the Boston Naming Test and above all facial recognition tests, like the Benton Facial Recognition Test), the performances of patients with Alzheimer’s disease differ significantly from those of patients with pseudodementia, who, moreover, do not show the reduced left hippocampal volume that instead characterizes patients with Alzheimer’s disease 33. However, it is widely felt that the use of neuropsychological tests alone (the traditional ones at least) does not allow good diagnostic definition 34 and indeed neurologists now have at their disposal other tools (in addition to neuropsychological tests) that can be applied at increasingly early stages to assist in the diagnostic workup of dementia (degenerative forms at least), namely biological disease markers.

Pseudodementia symptoms

Pseudodementia symptoms include 35:

- Intellectual impairment in patients with primary psychiatric disorder in which the features of intellectual abnormality resemble those of a neuropathologically induced cognitive deficit.

- This neuropsychological impairment is reversible and there is no apparent primary neuropathological process.

One of the features of pseudodementia, which have been debated in the literature, includes its reversibility. There is some evidence to suggest that in all cases of pseudodementia, some cognitive disturbances may persist 36. Furthermore, it is important to note that there is some evidence to suggest that the presence of pseudodementia in patients with depression increases the risk of dementia later on 36.

Clinically, many features have been reported to distinguish patients of pseudodementia from true dementia (Table 1). As is evident from (Table 1), patients with pseudodementia often have impairment of both recent and remote memory, in contrast to Alzheimer’s dementia, which is characterized initially by impairment of recent memory. Further, patients with Alzheimer’s dementia often try to confabulate and try to minimize their deficits, whereas those with pseudodementia tend to highlight their deficits 37. Patient with pseudodementia often has concurrent symptoms of depression, had marked distress due to his cognitive symptoms, did not make much effort to perform on simple cognitive tasks, and gave don’t know answer to many of the questions. All these features are consistent with pseudodementia.

Table 1. Distinguishing features of dementia and pseudodementia

Pseudodementia treatment

There have also been studies showing that cognitive impairments improve with treatment. In one of the earliest studies, Sternberg & Jarvik 38 reported that in endogenous depression subjects responding to a tricyclic antidepressant treatment, although performance on learning and short-term memory tasks remained impaired after treatment, there was improvement in immediate memory and this was related to degree of depressive recovery. Similar findings were reported by Calev et al. 39 and Bazin et al. 40 neither of which found residual impairments in either explicit (verbal and visual) or implicit memory tasks upon recovery. Similarly, Trichard et al. 41 in a controlled study of executive task performance in middle-aged subjects with severe depression, reported improved performance on the verbal fluency task but not the Stroop test upon recovery. A very significant finding was reported by Peselow et al. 42 who in a study of patients with unipolar depression treated with imipramine for 4 weeks, found significant improvement in all mnemonic measures only those responding to treatment. They concluded that in memory tasks performance, recovery of mood was associated with significant cognitive improvement. These findings have been reminded in a recent study by Egerhazi et al. 43, where cognitive impairment was found to improve partly in remission, suggesting that an individual’s current mood interacts with the ability to perform a cognitive task.

To summarize, results suggest that several cognitive domains especially those related to memory functions are improved with treatment of depressive disorders; however, several of them do persist. Thus a residual deficit in mnemonic and executive function appears to remain in some patients with a history of depression and specifically need to be investigate further because reversible cognitive impairment in late-life moderate to severe depression appears to be a strong predictor of dementia. More studies are needed to exactly understand the relationship of cognitive deficits in depression to crucial epidemiological variables such as age, treatment, duration and chronicity of illness and number of episodes 44. Thus, it is recommended to have a full dementia screening for patients suspected to have pseudodementia.

Pseudodementia medication

Evidence has emerged in recent years that the underlying cause of depression lies in dysfunctions not only of the known aminergic neurotransmitter systems, but also of other circuits, such as the glutamatergic ones; similarly, the role of other pathogenetic mechanisms, such as loss of synaptic plasticity in areas involved in regulation of emotion and affect, has increasingly been clarified as well 45. This has led to a growing interest in new molecules able to interfere with these systems and mechanisms, known to be involved in cognitive processes. However, the currently available antidepressant drugs have never been shown to have any efficacy on cognitive disorders 46. In recent years, vortioxetine has emerged as an agent capable of acting on the serotonergic system through a peculiar mechanism of action, completely different to those characterizing the previously available therapeutic options. Having being shown, both in various animal models and in clinical trials, to improve cognitive performance, in 2013, vortioxetine, which has a distinctive pharmacological profile, was approved in the European Union and in the USA for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adults. In 2015, the European Medicines Agency updated its data on the clinical efficacy of vortioxetine, stating that its effects include effects on cognitive and global functioning (to date, it remains the only antidepressant to which this applies).

References- Wells CE. Pseudodementia. Am J Psychiatry 1979;136:895-900.

- Kiloh LG. Pseudo-dementia. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1961;37:336–51.

- Perini G, Cotta Ramusino M, Sinforiani E, Bernini S, Petrachi R, Costa A. Cognitive impairment in depression: recent advances and novel treatments. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:1249–1258. Published 2019 May 10. doi:10.2147/NDT.S199746 https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC6520478

- Kang H, Zhao F, You L, et al. Pseudo-dementia: a neuropsychological review. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. 2014;17(2):147–154. doi:10.4103/0972-2327.132613

- Mahendra B. Depression and dementia: the multi-faceted relationship. Psychol Med. 1985;15:227–236. doi:10.1017/S0033291700023503

- Bulbena A, Berrios GE. Pseudodementia: facts and figures. Br J Psychiatry. 1986;148:87–94. doi:10.1192/bjp.148.1.87

- Alexopoulos GS, Meyers BS, Young RC, et al. The course of geriatric depression with “reversible dementia”: a controlled study. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150(11):1693–1699. doi:10.1176/ajp.150.11.1693

- Ownby RL, Crocco E, Acevedo A, John V, Loewenstein D. Depression and risk for Alzheimer disease: systematic review, meta-analysis, and metaregression analysis. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63(5):530–538. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.5.530

- Sáez-Fonseca JA, Lee L, Walker Z. Long-term outcome of depressive pseudodementia in the elderly. J Affect Disord. 2007;101:123–129. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2006.11.004

- Lovestone S. Alzheimer’ s disease and other dementias (including pseudodementias) In: David AS, Fleminger S, Kopelman MD, Lovestone S, Mellers JDC, editors. Lishman’s Organic Psychiatry: A Textbook of Neuropsychiatry. 4th ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell; 2009:566.

- Heser K, Bleckwenn M, Wiese B, et al. Late-life depressive symptoms and lifetime history of major depression: cognitive deficits are largely due to incipient dementia rather than depression. J Alzheimers Dis. 2016;54(1):185–199. doi:10.3233/JAD-160209

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. Arlington: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013.

- Rabins PV, Lyketsos CG. A commentary on the proposed DSM revision regarding the classification of cognitive disorders. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;19:201–204. doi:10.1097/JGP.0b013e3182051ac7

- McAllister TW, Price TR. Severe depressive pseudodementia with and without dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:626–629. doi:10.1176/ajp.139.5.626

- Mahendra B. Depression and dementia: The multifaceted relationship. Psychol Med. 1985;15:227–36.

- Sachdev PS, Smith JS, Angus-Lepan H, Rodriguez P. Pseudodementia twelve years on. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:254–9.

- Miskowiak KW, Ott CV, Petersen JZ, Kessing LV. Systematic review of randomized controlled trials of candidate treatments for cognitive impairment in depression and methodological challenges in the field. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016;26(12):1845–1867. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2016.09.641

- Fischer P, Simanyi M, Danielczyk W. Depression in dementia of the Alzheimer type and in multi-infarct dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:1484–7.

- da Silva Novaretti TM, D’Ávila Freitas MI, Mansur LL, Nitrini R, Radanovic M. Comparison of language impairment in late-onset depression and Alzheimer’s disease. Acta Neuropsychiatr. 2011;23:62–68.

- Sahin S, Okluoglu Önal T, Cinar N, Bozdemir M, Çubuk R, Karsidag S. Distinguishing depressive pseudodementia from Alzheimer disease: A comparative study of hippocampal volumetry and cognitive tests. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra 2017;7:230-9.

- David AS, Fleminger S, Kopelman MD, Lovestone S, Mellers JD, Folstein M. Lishman’s Organic Psychiatry: A Textbook of Neuropsychiatry. 4th ed. West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell Ltd.; 2009.

- McIntyre RS, Cha DS, Soczynska JK, Woldeyohannes HO, Gallaugher LA, Kudlow P, et al. Cognitive deficits and functional outcomes in major depressive disorder: Determinants, substrates, and treatment interventions. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:515–27.

- Risse SC, Raskind MA, Nocblin D, Sumi SM. Neuropathological findings in patients with clinical diagnoses of probable Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 1990;147:168–72.

- Sáez-Fonseca JA, Lee L, Walker Z. Long-term outcome of depressive pseudodementia in the elderly. J Affect Disord. 2007;101:123–9.

- Kral VA, Emery OB. Long-term follow-up of depressive pseudodementia of the aged. Can J Psychiatry. 1989;34:445–6.

- Paradiso S, Lamberty GJ, Garvey MJ, Robinson RG. Cognitive impairment in the euthymic phase of chronic unipolar depression. J Nervous Ment Dis. 1997;185:748–54.

- Marcos T, Salamero M, Gutierrez F, Catalán R, Gasto C, Lázaro L. Cognitive dysfunction in recovered melancholic patients. J Affect Disord. 1994;32:133–7.

- Abas MA, Sahakian BJ, Levy R. Neuropsychological deficits and CT scan changes in elderly depressives. Psychol Med. 1990;20:507–20.

- Beats BC, Sahakian BJ, Levy R. Cognitive performance in tests sensitive to frontal lobe dysfunction in the elderly depressed. Psychol Med. 1996;26:591–603.

- Small GW, Liston EH, Jarvik LF. Diagnosis and treatment of dementia in the aged geriatric medicine. West J Med. 1981;135:469–81.

- Kaszniak AW. Neuropsychological consultation to geriatricians: Issues in the assessment of memory complaints. Clin Neuropsychol. 1987;1:35–46.

- Kang H, Zhao F, You L, Giorgetta C, Venkatesh D, Sarkhel S, et al. Pseudo-dementia: A neuropsychological review. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2014;17:147-54.

- Sahin S, Okluoglu Önal T, Cinar N, Bozdemir M, Çubuk R, Karsidag S. Distinguishing depressive pseudodementia from Alzheimer disease: a comparative study of hippocampal volumetry and cognitive tests. Dement Geriatr Cogn Dis Extra. 2017;7(2):230–239. doi:10.1159/000477759

- McIntyre RS, Cha DS, Soczynska JK, et al. Cognitive deficits and functional outcomes in major depressive disorder: determinants, substrates, and treatment interventions. Depress Anxiety. 2013;30:515–527. doi:10.1002/da.22063

- Caine ED. The neuropsychology of depression: The pseudodementia syndrome. In: Grant KA, editor. Neuropsychological Assessment of Neuropsychiatric Disorders. New York: Oxford University Press; 1986. pp. 221–43.

- Sáez-Fonseca JA, Lee L, Walker Z. Long-term outcome of depressive pseudodementia in the elderly. J Affect Disord 2007;101:123-9.

- Caine ED. Pseudodementia. Current concepts and future directions. Arch Gen Psychiatry 1981;38:1359-64.

- Sternberg DE, Jarvik ME. Memory functions in depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:219–24.

- Calev A, Korin Y, Shapira B, Kugelmass S, Lerer B. Verbal and non-verbal recall by depressed and euthymic affective patients. Psychol Med. 1986;16:789–94.

- Bazin N, Perruchet P, De Bonis M, Féline A. The dissociation of explicit and implicit memory in depressed patients. Psychol Med. 1994;24:239–45.

- Trichard C, Martinot JL, Alagille M, Masure MC, Hardy P, Ginestet D, et al. Time course of prefrontal lobe dysfunction in severely depressed in patients: A longitudinal neuropsychological study. Psychol Med. 1995;25:79–85.

- Peselow ED, Corwin J, Fieve RR, Rotrosen J, Cooper TB, et al. Disappearance of memory deficits in outpatient depressives responding to imipramine. J Affect Disord. 1991;21:173–83.

- Egerhazi A, Balla P, Ritzl A, Varga Z, Frecska E, Berecz R. Automated neuropsychological test battery in depression – Preliminary data. Neuropsychopharmacol Hung. 2013;15:5–11.

- Kessing LV. Cognitive impairment in the euthymic phase of affective disorder. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1027–38.

- Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM. Synaptic mechanisms underlying rapid antidepressant action of ketamine. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(11):1150–1156. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12040531

- McIntyre RS. Using measurement strategies to identify and monitor residual symptoms. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74(Suppl. 2):14–18. doi:10.4088/JCP.12084su1c.03